|

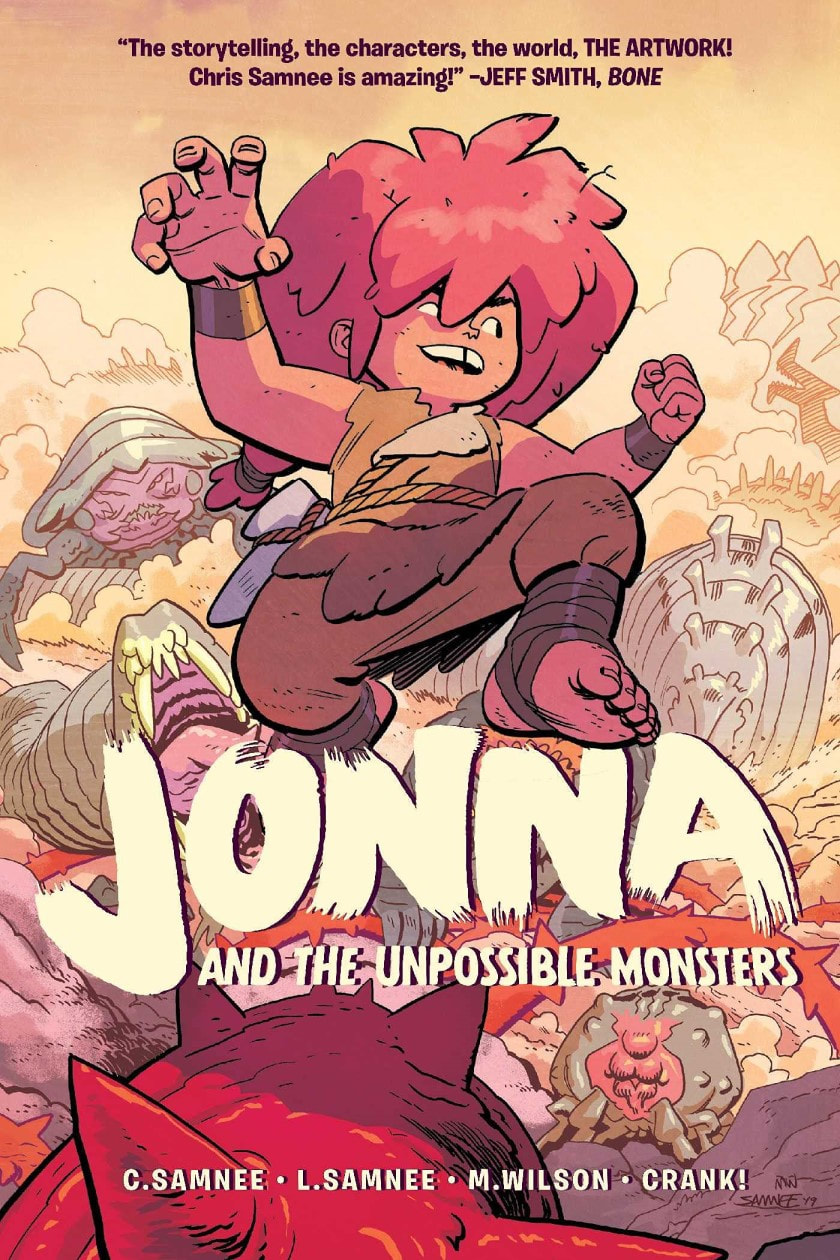

Jonna and the Unpossible Monsters. Book One. Written by Chris Samnee and Laura Samnee. Drawn by Chris Samnee. Colors by Matthew Wilson. Lettering by Crank! (Christopher Crank). Oni Press, August 2021. ISBN 978-1620107843, $US12.99. 112 pages. Jonna and the Unpossible Monsters has a premise that was just waiting to happen, one that somebody, somehow, had to get around to: a postapocalyptic children's fantasy about fighting giant, kaiju-like monsters. There's a touch of Jack Kirby's Kamandi, the Last Boy on Earth about this, and maybe a touch of Pacific Rim too. Co-creators Laura Samnee and Chris Samnee describe Jonna as a story they "could share with [their] three daughters," something created "for them" but also "inspired by them"; the comic, though, will appeal to action-starved fans of Chris Samnee's work on such superhero comics as Thor the Mighty Avenger, Daredevil, Black Widow and Captain America (or his current martial arts fantasy with writer Robert Kirkman, Fire Power). The heroic Jonna is a wild, monster-clobbering girl with a whiff of Ben Grimm or Hellboy. She comes across as untrammeled, almost feral, yet delightful. When Jonna goes missing in a ruined, kaiju-ravaged world, her older sister Rainbow – the more fretful, responsible one, naturally – tries to find her, then corral and (re)civilize her. Jonna, though, remains a unpredictable force of nature. You don't need to know much more; the first half dozen pages give you whopping big monsters, and plenty of synthetic worldbuilding. There's a sense of the familiar about all of it, but novelty and excitement too. By now it's almost a cliché to speak of Chris Samnee's masterful storytelling and sheer chops (I've paid tribute before). It is true that I will read just about anything drawn by him, especially when it's colored by Matt Wilson, his steady collaborator for more than a decade. Granted, I got impatient with Fire Power within a few issues. Though I dug its bang-up start, Fire Power strikes me as a shopworn White martial arts fantasy à la Iron Fist; it's tropey, and conceptually a bit tired. I've stayed with it, however, because of Samnee and Wilson's visuals, and it has become my monthly dose of old-school craft and loveliness, balancing breathless action with an Alex Toth-like elegance. Samnee manages to be polished and rugged at once; his drawing offers classicism and grace, but with a terrific infusion of energy. Jonna, I think, may be the best thing he has ever done: the pages sing, and roar, and astonish with their gusty action and playfulness. Freed somewhat from the stylized naturalism of mainstream superhero comics (though that skill set is still very much in evidence), Jonna cartoons with a joyful freedom. Wilson's coloring, too, is eye-wateringly good. All this is my way of saying that Jonna is craftalicious and affords plenty of gazing and rereading pleasure after the initial readerly sprint. But what does it amount to? On some level, it remains a kind of superhero comic, not only because Jonna packs a mean punch but also because a couple of other characters discovered along the way, Nomi and Gor, are seasoned fighters as well (Nomi boasts powerful prosthetic arms). So, this is a slugfest. But there's more: moments of poignancy, sisterly anxiety, and Jonna's weird, ferine energy and charming social cluelessness. And the Samnees allow a certain melancholy to creep in; the world of Jonna is a fallen one, full of sundered families, lost loved ones, bereavements. In one scene, a ragtag group of survivors huddles around a fire, and their dialogue says a lot: My whole family gone. My home destroyed. My village destroyed. Everything destroyed. Without pressing the point, the story has a genuinely apocalyptic feel that, to me, reeks of COVID. That it manages to be cockeyed and funny at the same time is no small feat. Though billed as a children's story, Jonna is just as much for grownups. The book (originally serialized in floppy form) splits the difference between direct market-oriented cliffhanger series and middle-grade graphic novel, so it's courting multiple audiences. Moreover, a theme of "families and belonging" (as the Samnees put it) threads through the book, familiar from many an animated family film, and like such films Jonna offers adults a kind of reassurance even as it aims for kids. That is, it offers childhood as a cure for ruin and heartbreak. The basic ingredients are familiar – there's nothing revolutionary about this tale – but I'm at a time in my life where seeing kids wallop monster does me a world of good. This first volume (a second is promised for Spring 2022) sets up some mysteries, not least the mystery of Jonna herself, and doesn't answer very many questions, but I enjoy paging through it and rereading it. In fact, I enjoy it more than I can say. PS. The excellent magazine PanelxPanel, by Hass Otsmane-Elhaou and company, devoted a good chunk of its May 2021 issue (No. 46) to Jonna, and includes a revealing interview with Chris Samnee. Plus, the issue contains other articles on depictions of children and on young readers' graphic novels. Well worth checking out!

0 Comments

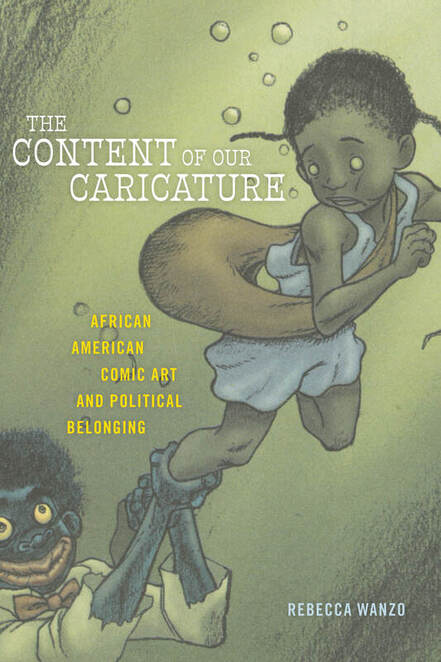

The 2021 Eisner Awards were announced in a virtual ceremony or video released on Friday, July 23, part of Comic-Con@Home. The ceremony, hosted (once again) by actor Phil LaMarr, runs just over an hour and can be viewed via YouTube on the Comic-Con International channel: https://youtu.be/RuVslpoC2nI This year's was a solid and fairly satisfying Eisner Awards crop, and mostly unsurprising, given the ballot announced on June 9. Out of the thirty-two award categories, I was mildly surprised by five or six. Going into the ceremony, I had strong feelings about just three or four categories. In almost all cases, my daughter Nami was able to call the winner just before LaMarr announced it! These past few weeks, I’ve been checking out a number of Eisner nominees and winners from my local library, the LAPL. Good reading! I congratulate all of this year's winners, and, again, particularly congratulate the nominees in the Academic/Scholarly Work category. Readers, do seek out all the books in that category, especially the Award-winner, Rebecca Wanzo's The Content of Our Caricature, which is innovative and important! As I've said before, when that book came to my mailbox, I stood transfixed and read a whole chapter before even sitting down. The book is brave, startling, and bracing: a must. My congratulations to Dr. Wanzo on this well deserved (further) recognition! PS. I hope I will be able to write up some of my recent reading here at KinderComics. This is a time of bereavement and struggle for my family, so my writing and reading time is sorely limited, but I do hope to reconnect, here, in this space I've tended for so long. Peace, everybody.

The nominees for the 2021 Will Eisner Comics Industry Awards – the most prestigious set of awards given within the US comic book and graphic novel industries – were announced on June 9. This year’s judging panel consisted of comics retailer Marco Davanzo, Comic-Con International board member Shelley Fruchey, librarian Pamela Jackson (San Diego State University), creator/publisher Keithan Jones, educator Alonso Nuñez, and comics historian Jim Thompson. As usual, the ballot recognizes an eclectic mix of material, with awards in thirty-two categories, including the following three young-reader categories: Best Publication for Early Readers (up to age 8)

Wow, what a list! This year’s ballot looks smart and interesting to me. As always, I could gripe about oversights, omissions, and puzzling choices. Of course! I’ve been an Eisner judge myself (2013), so I know that the job is challenging, even overwhelming. I get it. The Eisners represent several different communities (after all, they are not a guild prize like the Oscars or the Grammys) and it’s not easy for the yearly ballot to satisfy everyone. That said, I am learning a lot by looking up this year’s nominees. In addition to the nominees in the dedicated young-reader categories above, there are nominations in many other categories that may interest followers of children’s and young adult comics. What follows is not an exhaustive list, but just a few items that I noticed: Best Single Issue:

Readers, I urge you to seek out all of these works!  On a personal note, I'm honored that the book I co-edited with Bart Beaty, Comics Studies: A Guidebook (Rutgers University Press), has been nominated for an Eisner in the category Best Academic/Scholarly Work. This is a testimony to the superb work of our co-contributors: Jan Baetens, Isaac Cates, Mel Gibson, Ian Gordon, Martha Kuhlman, Frenchy Lunning, Brian MacAuley, Matt McAllister, Andrei Molotiu, Philip Nel, Roger Sabin, Kalervo Sinervo, Marc Singer, Theresa Tensuan, Shannon Tien, Darren Wershler, Gillian Whitlock, and Benjamin Woo. Our Guidebook is in excellent company. The other nominees for Best Academic/Scholarly Work are:

More than one of these books has fundamentally changed the way I look at my field. Again, readers, I urge you to check out these thought-provoking works. Also, check out the work in the other comics scholarship category, that of Best Comics-Related Book:

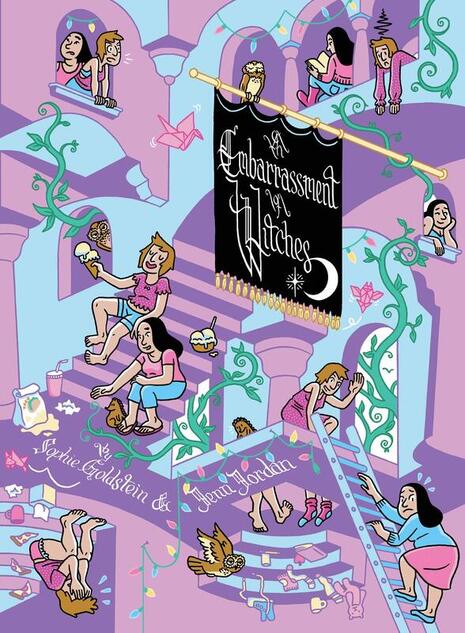

An Embarrassment of Witches. Written by Jenn Jordan and Sophie Goldstein; art by Sophie Goldstein. Coloring assistance by Mike Freiheit; calligraphy by Carl Antonowicz. Top Shelf, 2020. ISBN 978-0593119273, $US19.99. 200 pages. Lately I've been reviewing Bildungsromane about young witches in training (here, here, and here). I thought An Embarrassment of Witches would be one of those, but it really isn't. Yes, it's a coming-of-age story, but it's also a grad school comedy about the experiences of two fairly new adults (not young adults in the adolescent sense) whose loved ones are high-powered academics or wannabes living in a rarified intellectual world ripe for satire. It happens that this world is one in which magic is commonplace, one where you can go to grad school to study "metamystics," and where shopping malls include businesses like Taco Spell and Aleistercrowley & Witch. But the story does not focus on learning witchery or spellcraft. It deals with applying for jobs and school, with internships, and with tense people having relationships at a bemusing transitional moment in their lives. It reads like a Friends-style sitcom combined with an academic novel, but is not as acrid as that might sound. Tonally, it reminds me of John Allison's splendid college comedy, Giant Days; its character writing is just as adult and just as piquant, and it conveys a similar sense of benign absurdity. Briefly, the story focuses on two best friends and roomies, Rory (Aurora) and Angela, and how their friendship is sorely tested by the moves they have to make toward autonomous adulthood: feckless Rory walks away from her supercilious boyfriend and begins looking for a new direction in life, while Angela takes an internship supervised by, of all people, Rory's mother, a famed and fearsome academic. Lies, evasions, and secrets result in a complicated tangle. Eventually, Angela and Rory have to renegotiate the terms of their friendship on a more adult basis. The plot reveals the unreliability and stumbling humanity of just about everybody, without demonizing anybody (characters who at first appear flat turn out to have depths). The book is smart, funny, and endlessly inventive, and scatters little comic jewels on almost every page. Rory and Angela are knowingly and subtly written, with great attention to their brittleness and quirks and, especially, the mostly unspoken complexities of their relationship. This is witty, human, open-hearted stuff. Art-wise, An Embarrassment of Witches is a formally inventive knockout. The character designs are sharp and distinctive, the visual worldbuilding is a hoot, and the book looks like no other. Goldstein dispenses with gutters and borders, favoring jampacked full-bleed pages in which the panels rub right up against each other. The results are a bit overwhelming due to sheer density, but that jibes with the book's emphasis on complex social dynamics. It also makes the book a delight to page through again and again (the disorienting, Escher-like cover is just a hint of the pleasures and challenges inside). The limited color palette — two purples, a near-turquoise green, celeste blue, and a kind of mellow yellow — may sound iffy in the abstract, but works brilliantly in practice, making the book into a cohesive world of its own. All this is to say that the wittiness of the story is matched by an outpouring of visual wit. In short, An Embarrassment of Witches is a full-on delight.

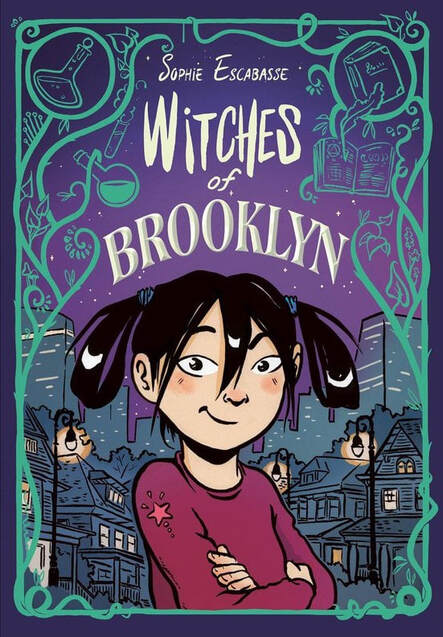

Witches of Brooklyn. By Sophie Escabasse. RH Graphic/Random House, 2020. ISBN 978-0593119273, $US12.99. 240 pages. In this middle-grade urban fantasy, the first in a planned trilogy, orphaned tween Effie is adopted by her eccentric aunts Selimene and Carlota, herbalists and acupuncturists who live in a quaint Victorian house in Flatbush. As it turns out, her aunts are also “miracle makers,” witches whose powers can bend reality and time—and Effie discovers that those powers run in the family. When a vaguely Taylor Swift-like pop star idolized by Effie runs afoul of some ancient magic and needs a cure, Selimene and Carlota take Effie into their confidence, and her training in magic begins. A clever, if rigged, story ensues, jammed with business, as Effie bonds with her aunts, makes friends at school, discovers the hazards of having power without knowledge, and becomes disillusioned with her former idol—but also saves her. The story abounds in Harry Potterisms and other well-worn tropes, and the frantic plot works against the bids for soulful characterization: for example, Effie begins as an embittered foster child with a chip on her shoulder, but then abruptly embraces living with her aunts, leaving all resentments and uncertainties aside. Hints of past unhappiness and family intrigue involving her late mother remain vague, perhaps foreshadowing sequels. There are plenty of loose ends. Author Sophie Escabasse’s style seesaws between joyous energy and fussy detailing. Her layouts are restless and dynamic, the traditional grids often enlivened by inset panels, frame breaks, and diagonals. There’s an enjoyable, exploratory quality about all this—the delight of seeing what a page can do—though the cluttered detail and overbusy coloring bog things down a bit. (On some pages, backgrounds are grayed out to bring the characters forward, which I think helps.) The characters are all distinct, with different silhouettes, head shapes, and faces—so different that they almost seem to have been drawn by different artists. Effie’s aunts are the most vividly realized and charming; in particular, Selimene, mercurial and feisty, stands out from the general busyness, with a comical design that recall Escabasse’s avowed influence André Franquin. Overall, Witches of Brooklyn strikes me as pretty good but also very familiar—so, I’m lukewarm toward it, despite its many good, smart moments. The sequels, I hope, will aim for less obvious plot-rigging, more rooted and consistent characterization, a sharper sense of what magic means and can do in this story-world, and, visually, not so much over-egging of the settings and details. As is, this first book crams in about three books’ worth of material and potential—I’d like to see Escabasse explore her world at a more deliberate pace. The second book reportedly will drop at the end of August.

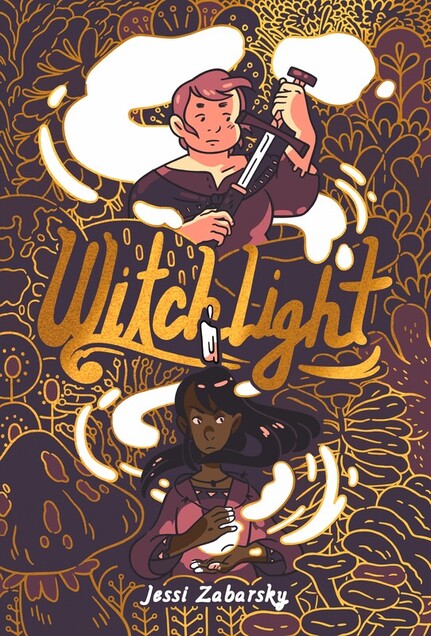

Witchlight. By Jessi Zabarsky. With coloring by Geov Chouteau. RH Graphic/Random House, 2020. ISBN 978-0593119990, $US16.99. 208 pages. I guess you say that this review is part of an occasional series (heh). In an unnamed land—a marvelous, culturally syncretic fantasy world—two young women undertake a magical quest and, as they go, learn how to care for one another. One of them, Lelek, volatile and enigmatic, is a witch who has lost half her soul. The other, her newfound friend (well, at first her kidnappee) Sanja, is determined to help find it. Love blooms between them—a matter of blushing shyness at first, but then owned and enjoyed with a winning matter-of-factness. As they travel, Lelek and Sanja scare up money by challenging local witches to duels, but often end up learning from those same witches; their travels uncover woman-centered communities and hints of matriarchal lore and magic. The larger culture hints at witch-hunting and misogyny, and this leads to a harrowing twist in the final act, but also, by roundabout means, to the resolution of a mystery and a ringing affirmation of Lelek, Sanja, and everyone they’ve befriended en route. Originally published by Kevin Czap’s micro-press Czap Books in 2016, Jessi Zabarsky’s Witchlight is a gorgeous and soulful feast of cartooning in a clear-line but vigorous, rounded style (which reminds me a bit of Czap’s own). It grows more confident in its linework and layouts as it goes. Beautifully colored by Geov Chouteau, the pages sing with an assured minimalism and harmony. I suppose the backstory and conflicts could be established more firmly—the plot might be clearer—but on the other hand, I enjoyed immediately diving back into the book to better understand its dreamlike premises. The book’s feminist, antiracist, and queer-positive ethos are a part of that dream and arise organically from the world Zabarsky has created; she uses her secondary world to imagine a better one. The utopian vibe is complicated by emotional and social nuances and an earned sense of loss and struggle. More than anything, Witchlight radiates a sense of love, offhand intimacy, and the thrills of self-discovery. Zabarsky clearly delights in her characters. She is a great cartoonist, with another graphic novel promised from RH Graphic by year’s end. I can't wait!

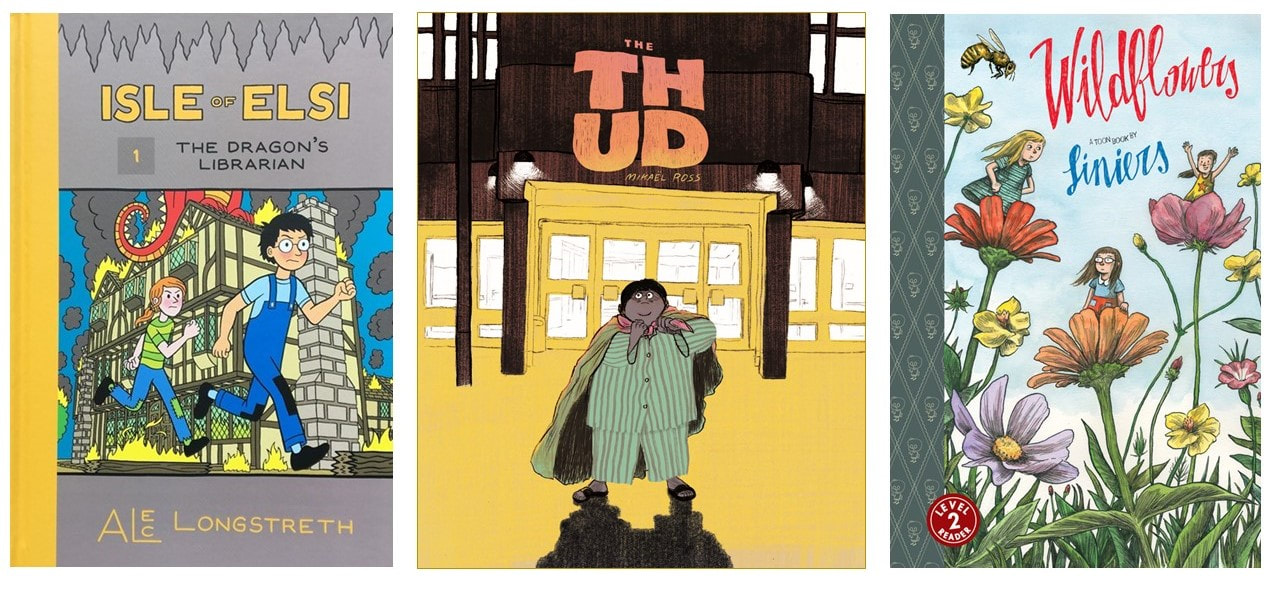

News: I'm glad to have found a new connection and new venue for some of my writing about children's and young adult comics: SOLRAD, the online literary magazine for the comics arts. SOLRAD, published by the nonprofit Fieldmouse Press, is the work of a dedicated editorial team and a burgeoning community of artists and thinkers. Since launching in January 2020, it has offered comics journalism, criticism, new comics, and an inclusive space. Recently I've been publishing reviews with SOLRAD under the KinderComics tag, with particular help from publisher Alex Hoffman, editor-in-chief Daniel Elkin, and acquiring editor Rob Clough. I'm proud to be working with them. I've published three KinderComics posts with SOLRAD so far: reviews of Alec Longstreth's Isle of Elsi: The Dragon's Librarian (January), Mikaël Ross's The Thud (April), and Liniers's Wildflowers (May). Each has been a learning experience and a pleasure, and each has benefited from eagled-eyed editing by Team SOLRAD.  I hope and plan to write regularly for SOLRAD. It may become my main venue for children's and YA comics reviews. I'm not sure yet. Suffice to say that I've been craving a new venue, one that could draw its own loyal audience. I've been wanting new ways to get my comics reviews out into the world. KinderComics was born in 2011 as a column at The Comics Journal (tcj.com), a site and brand I've loved for years that remains dear to me. However, I stalled out there, unable to find a rhythm. Years later, this blog, KinderComics.org, revived the idea, and for the past three years it has been a joy to write in this space — but then again a frustration when other work got between me and the blog, causing me to lose the momentum needed to sustain a good-sized readership. Given my academic work, I'm afraid I cannot post weekly. Nor have I been able to post the kinds of interviews and longer features I dreamed of. I've come to realize that I need to be in the company of other writers and partnered with a group that has its own momentum. With that in mind, as I mull over what to do here at KinderComics.org, I'd like to invite you, my readers, to follow me over to SOLRAD (if indeed you don't already have SOLRAD bookmarked!). Whether to put this blog on hiatus or not is a decision I won't make until sometime after I publish my next review in SOLRAD (in the next few weeks). I may use this space to post brief capsule reviews or some kind of semi-weekly reading journal. Again, I'm not sure. In the meantime, I'm delighted to be working with the SOLRAD team!

Man, I've been trying to catch up! What you see here is a short and personal list (though longer than the list I contributed to SOLRAD's Best) of new comics in print that kept me busy and happy, or productively on edge, in 2020 to early 2021. Most had 2020 publication dates, officially (I think). These twenty-five books or series are works I'll remember for a long time: books that felt urgent and/or mesmerizing to me and that fell into a bedside pile of "notable comics." I'm afraid these twenty-five do not include great webcomics, or short comics found outside of book or booklet form. Nor does it include certain books I might have admired had I been able to get to them. There is so much to catch up on, and so much more that I just can't include here, lest I make my head explode! Click on a book's cover to see a webpage with more info about the book. Note that many of these titles are not intended for children or young adults. PS. The two books that compelled me to redraw my mental map of comics this year were Dancing After TEN, by Vivian Chong and Georgia Webber, and The Sky Is Blue with a Single Cloud, a collection of comics by Kuniko Tsurita (1947-1985), masterfully curated and placed in context by Ryan Holmberg. Dancing After TEN, a collaborative memoir, overturns assumptions about the so-called autobiographical pact (as in, what exactly does the "auto" in autographics mean?), while also providing, with perhaps inevitable irony, powerful visual means of conveying one person's experience of what it meant to go blind. I think it's going to be a landmark among graphic memoirs depicting disabled experience. And the Tsurita volume, well, the surreal, elliptical, and haunting manga collected in it, the sheer beauty of the evolving artwork, the sometimes puzzling but always intriguing way it pulls me out of myself, and the superb contextualizing essay by Holmberg and Asakawa — it all adds up to an incredible gift: an important act of historical recovery as well as a bundle of great comics. BTW it's been an amazing year or so for scholar-translator-editor Holmberg, from The Man without Talent, The Swamp, and The Sky Is Blue with a Single Cloud, to his own personal scholarly/travelogue book, The Translator without Talent, to his reportage on antiracist comics activism in Graham, North Carolina. I first met Holmberg at (I think) the 2004 ICAF conference, and he's been expanding my understanding of comics ever since. Man, he deserves a medal. And I suppose Drawn & Quarterly, which has published translations of so many outstanding Japanese and Korean comics lately, is once again my Publisher of the Year. Thank goodness for them.

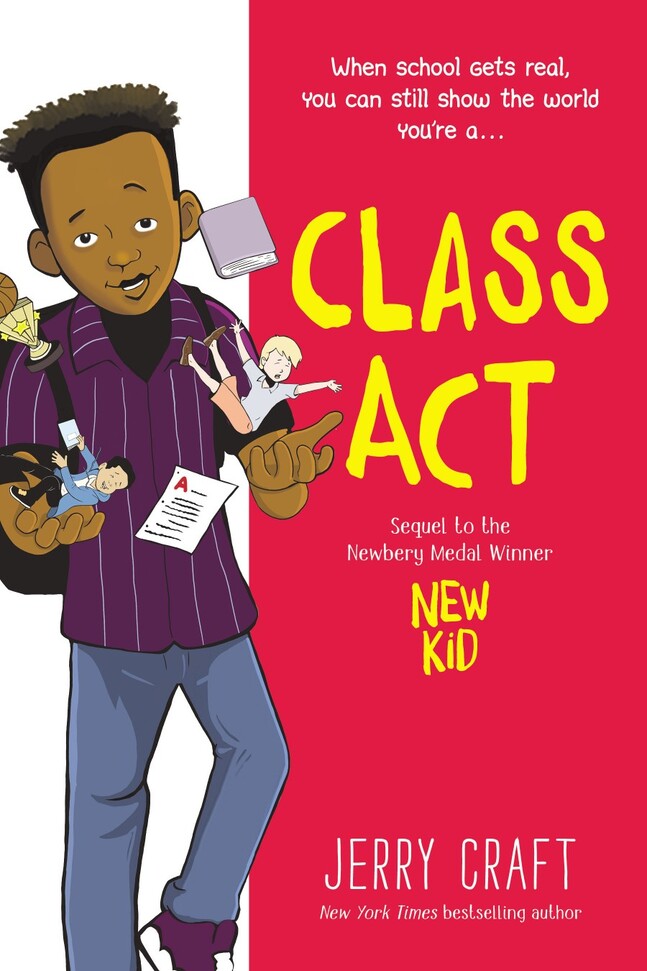

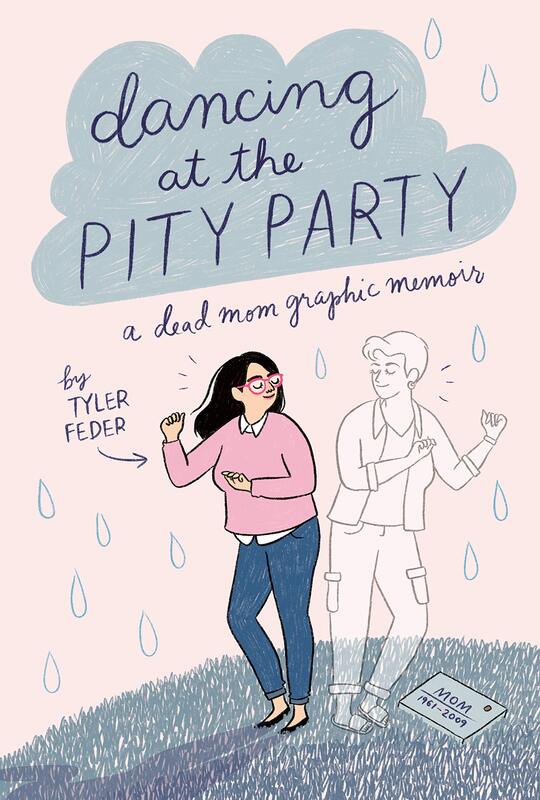

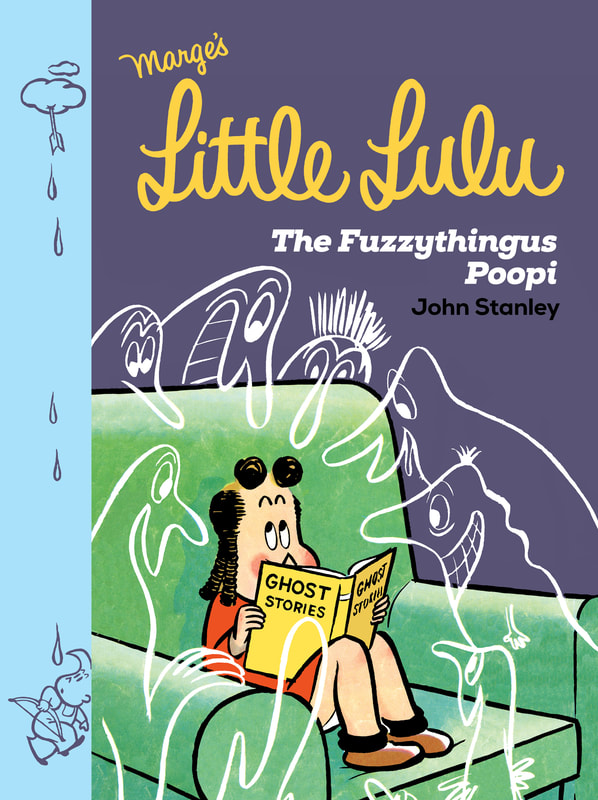

Class Act. By Jerry Craft. HarperAlley / Quill Tree Books, 2020. ISBN 978-0062885500, $US12.99. 256 pages. Billed as a “companion” to Jerry Craft’s Newbery-winning New Kid, Class Act is actually a direct sequel, following Jordan Banks and his schoolmates into the next year, but this time focusing less on Jordan and more on his friend Drew. The opening pages go to Jordan, and again his work as a budding cartoonist punctuates the story, in the form of comic strips notionally drawn by him—but Drew’s challenges, as a Black scholarship boy raised by a hard-working grandmother, soon take center stage. Drew’s pained awareness of class difference tests his friendships with Jordan and their affluent White schoolmate, Liam, and the plot tracks the awkward social negotiations among the three of them. Once again, Craft’s kids, brave and self-knowing, navigate the minefields of race and class, dogged by an inescapable sense of the things they don’t have in common; once again, their teachers are fumbling and oblivious. This time, Craft satirizes the inane efforts of their school, the tony Riverdale Academy, to extol “diversity”: teachers are dispatched to a conference called the National Organization of Cultural Liaisons Understanding Equality, and the school makes a failed effort to “adopt” a sister school whose working-class students of color don’t know what to make of Riverdale’s privileged, “bougie” atmosphere. As in New Kid, Craft observes all this in an amused, good-humored way, while never forgetting that difference can make all the difference. One tense scene depicts Jordan’s father being stopped by a White cop when driving in Liam’s posh neighborhood; moments like that affirm that Craft is playing for keeps, drawing out humor from real pain. Class Act, then, is smart and careful as well as high-spirited – though its story, I think, is more diffuse than that of New Kid, its stakes not quite as clear. (It would help to reread New Kid just before reading this one.) The book is busy and teems with in-jokes, including nods to comics and children’s book authors; sidelong gags are everywhere, to the point of distraction. More impressive is Craft’s diverse cast of distinctive, well-defined kids, many of whom get moments in the spotlight; they actually talk to each other, in courageous, meaningful ways, and Craft understands the subtle dynamics among them. You can tell he likes them. I confess that the art, with its jumbled, cut-and-paste style, clip-art elements, and CG backgrounds, put me off at first (I felt the same about New Kid). The work has an overbusy finish that mixes cartoony flatness with gradient coloring – an uneasy compromise. But Craft builds smart pages, and his socially engaged storytelling, once more, rings sharp, wise, and true. Dancing at the Pity Party: A Dead Mom Graphic Memoir. By Tyler Feder. Dial Books, 2020. ISBN 978-0525553021, $US18.99. 208 pages. Tyler Feder’s mother Rhonda Feder (née Hoffman) died of cancer when Tyler was nineteen, more than ten years ago. This memoir recounts Rhonda’s illness and death, her funeral, and the enduring sadness that has been part of Tyler’s life ever since—sometimes a still-raw, lacerating grief, sometimes a bittersweet nostalgia. That may sound just about unendurable: a self-pity party indeed. But what this book really does is pay homage to Rhonda Feder, evoke her particular, idiosyncratic self, and capture the way profound memories, very specific and odd memories that no one else could understand, arise unpredictably from quirky particulars and chance encounters. Yes, the book depicts, in fact enacts, grieving as a process, one that never quite ends, but it does so with verve, comic frankness, and surprisingly many laughs. In fact, at first, in the book’s opening pages, I wasn’t ready for Feder’s almost nonstop humorous flippancy, her many comic asides, satiric observations, and zingers. This sort of larking around in the shadow of death seemed like the very definition of Too Soon (although her mother died so long ago). To me, Feder’s approach at first felt too self-involved. But soon, very soon, the book crafts a precise portrait of Rhonda as a personality, lovingly remembered in all her quirks, the emotional, mental, and physical subtleties that made her who she was. Her eccentric liveliness, and that of her family, come through strongly, and Feder, in an unassuming and uncluttered style, balances deep sadness and irrepressible good humor, in a lovely, unforgettable tribute. Helpfully didactic at times (“Dos and Don’ts for dealing with a grieving person”), the book is mainly witty, personable, and compulsively readable—a remarkable example of how art, as Feder says, can “turn the crap into something sweet.” Little Lulu: The Fuzzythingus Poopi. By John Stanley, with Charles Hedinger, Irving Tripp, et al. Edited by Frank Young and Tom Devlin. Drawn & Quarterly, 2020. ISBN 978-1770463660, $US29.95. 276 pages. Lovingly edited, gorgeously designed, this second volume in Drawn & Quarterly’ deluxe hardcover Little Lulu series reprints more than thirty stories and strips, and a score of beautiful covers, that ran in the Dell comic book series circa 1949-1950. Written and laid out by John Stanley, these brilliant, economical, tightly wound comics were among the best of their time. They hold up well. Much has been said about Lulu as a feisty feminist icon who gets the drop on the sexist, obtuse, often mean-spirited boys in her neighborhood, and that’s true (the book’s introduction by Eileen Myles underscores that point); I was also struck, though, by the notes of human vulnerability and doubt in her characterization, by the signs of frailty and uncertainty that Stanley’s heroes often show. Lulu can be bullied, and Lulu can be hurt, but that makes her victories all the sweeter—she has real character. Stanley packs a surprising amount of human complexity into these condensed fables and gags. The tales are often absurd, sometimes satirical (such as “The Old Master,” a takedown of the art world), and always exquisitely timed, with gags and payoffs that depend upon very precise rigging. D&Q’s Lulu series is one of the best things happening in comics right now, even though the comics themselves are old. Drawn & Quarterly provided a review copy of this book.

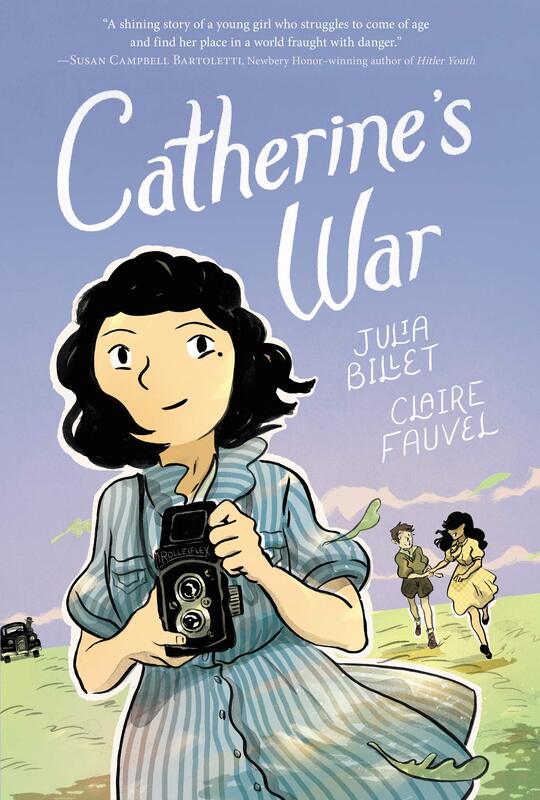

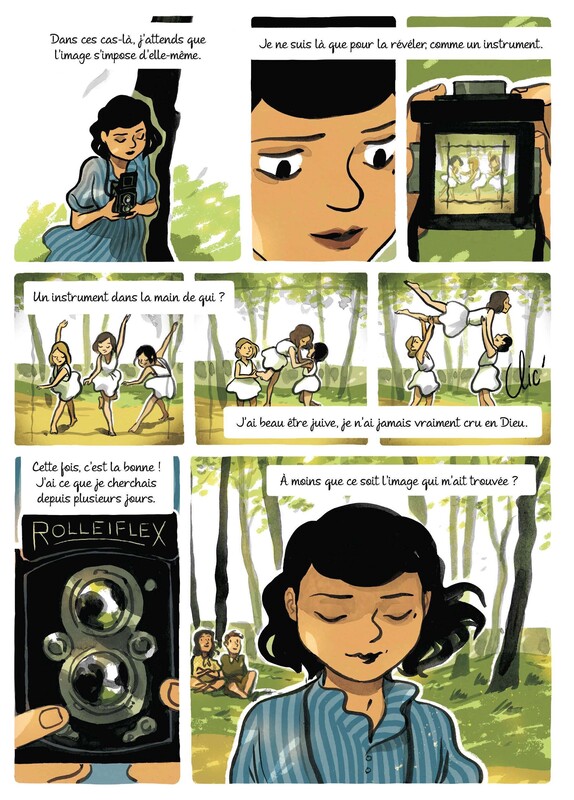

Catherine’s War. By Julia Billet and Claire Fauvel. Translated from the French by Ivanka Hahnenberger. HarperAlley, 2020. ISBN 978-0062915597, $US12.99. 176 pages. Catherine’s War is a finely shaded, beautifully cartooned, and engrossing book that ends much too abruptly. A historical novel stenciled from real events, it has been translated from the Angoulême Youth Prize-winning BD album La guerre de Catherine (Rue de Sèvres, 2017), which adapts Julia Billet’s prose novel of the same name (2012). Billet’s novel itself freely adapts, or at least draws inspiration from, the wartime story of Billet’s mother, Tamo Cohen, one of thousands of hidden children uprooted by the Holocaust: Jewish children sheltered from the Nazis, often in Catholic convents or among Gentile families. In real life, Tamo Cohen did attend the Sèvres Children’s Home (in fact a progressive, student-centered school), as does the protagonist of this novel, Rachel Cohen, and she did flee the Nazis, and she was renamed to pass as a Gentile, just as Rachel here is renamed “Catherine Colin.” But, as Billet admits in her notes, the story of Catherine’s War “remains a story”—a historical fiction interwoven with truths. Billet imagines Rachel/Catherine as a young photographer whose images of WWII are successfully exhibited in a Parisian art gallery soon after the war (an exhibition that replays many experiences depicted earlier in the book). Further, Rachel’s narration, implicitly, comes from her journal—so, she is an artist in words as well as pictures. In that sense, Catherine’s War becomes a Künstlerroman as well as a wartime tale of life on the run. Thematically, it reminds me of books like Whitney Otto’s ensemble novel Eight Girls Taking Pictures (2012), a fictionalized biography of eight women photographers, and comics like Isabel Quintero and Zeke Peña’s Photographic (2017), a YA biography of famed Mexican photographer Graciela Iturbide. Reframing Tamo Cohen’s story within the history of photography, Billet casts her mother, or rather Rachel, as a visual witness to the terrors of war. Armed with a Rolleiflex (like Robert Capa – or Annemarie Schwarzenbach?), the fugitive Rachel/Catherine becomes a chronicler as well as autonomous artist, even as she rushes from one shelter to the next to evade the Nazis. For all that, Catherine’s War is not explicitly violent. Though fear is ever-present, intimations of war and Holocaust are discreet; we never see the dreaded roundups or camps, or combat (though overheard dialogue among Resistance fighters does imply sabotage). The point of view is limited to what a child in hiding, pretending to live out her normal life, might have witnessed. Trauma is suggested by the extent to which Rachel and other young people help each other cope with it. The various children depicted (the story begins at the Sèvres home, and Rachel most often travels with other kids) are wounded by the shocks and partings they have to endure, yet they are resourceful, brave, and unselfish—not to the point of absurd angelic idealization, thank goodness, but in a tense, believable way. (Billet’s trust in young people mirrors the radical teaching philosophy of the Sèvres school.) Multiple scenes depict the challenge of trying to keep cover stories straight, the distrust stoked by constant surveillance, and the dread of giving the game away. Yet the novel is so discreet that it takes Billet’s endnotes to flesh out the terrible context of WWII. Those notes clearly anticipate a young audience, and I note that the book is blurbed by a notable writer of children’s nonfiction, Susan Campbell Bartoletti, whose work (Hitler Youth, Kids on Strike!, etc.) often extols young people’s activism and recounts harrowing historical facts with candor but also due sensitivity. Decorous would describe this book’s approach: from the story’s quiet hinting, to Claire Fauvel’s rippling brush-inking, gentle watercolors, and borderless panels, to the prim digital lettering (by David DeWitt). A genteel aesthetic overlays everything, conferring delicacy despite the nightmarish world evoked. What makes all this work is Fauvel’s patience, empathy, and attention to detail: from the opening pages, she tracks Rachel and the other characters with exquisite care, and their feelings, both spoken and unspoken, register honestly. Fauvel’s visual storytelling, if understated, is fluid and confident, moving characters about gracefully and capturing unwritten nuances in most every scene. She really cares about these characters. In short, Catherine’s War is smartly laid out, superbly drawn, and piercing. (For insight into Fauvel's process, and the book's production, see Billet's VanCAF presentation from last spring: a slideshow and talk captured on video, subtitled in English.) Not everything in the book works. There are moments where the book seems determined to spell out, rather than suggest, its messages—passages that seemed forced. In particular, a postwar scene depicting the ritual shaming (head-shaving) of French women accused of Nazi collaboration seems underdone; it doesn’t explain what’s at stake, and Rachel’s rejection of the shaming mob doesn’t register (though Billet’s endnotes work hard to underscore the didactic point). Also, as the book accelerates toward its end, things happen rather too fast. Both a crucial relationship and the postwar arc of Rachel’s life are sketched in abruptly over the last couple of pages. (It turns out that there’s a sequel, published in French in 2020, so perhaps the ending was meant to be a springboard?) When I turned the final page, I felt as if I was still in midair. That said, the gnawing dissatisfaction I felt got me to reread the book, which sharpened my appreciation of Fauvel’s subtle artistry. As I say every so often, I’d be glad to read more.

|

Archives

April 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed