|

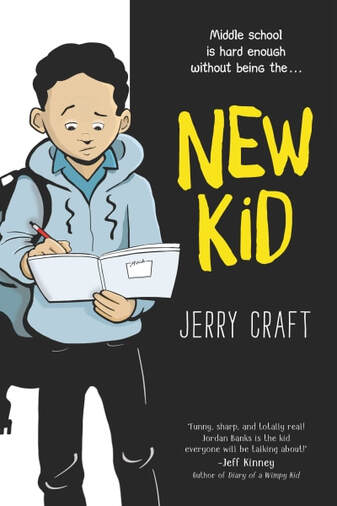

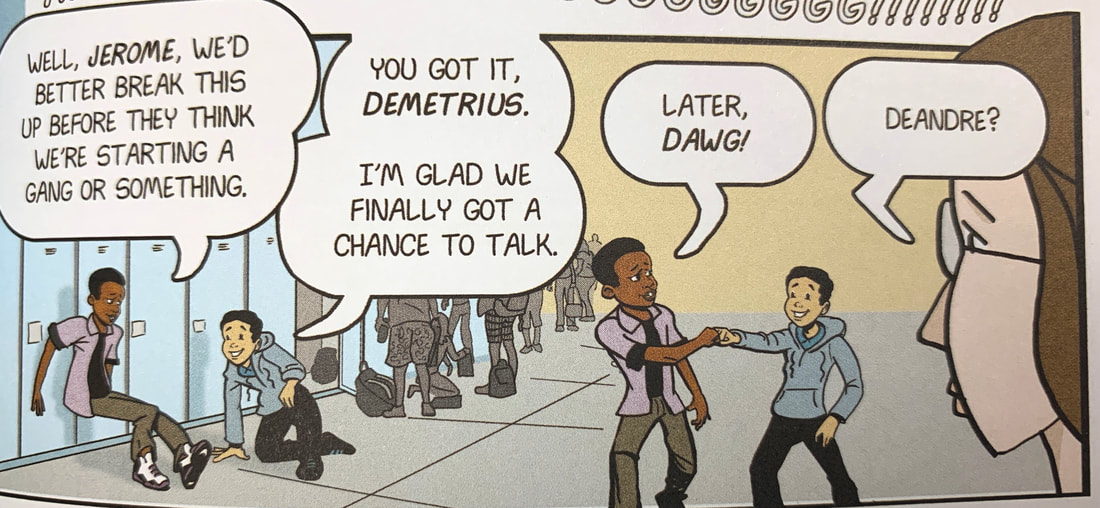

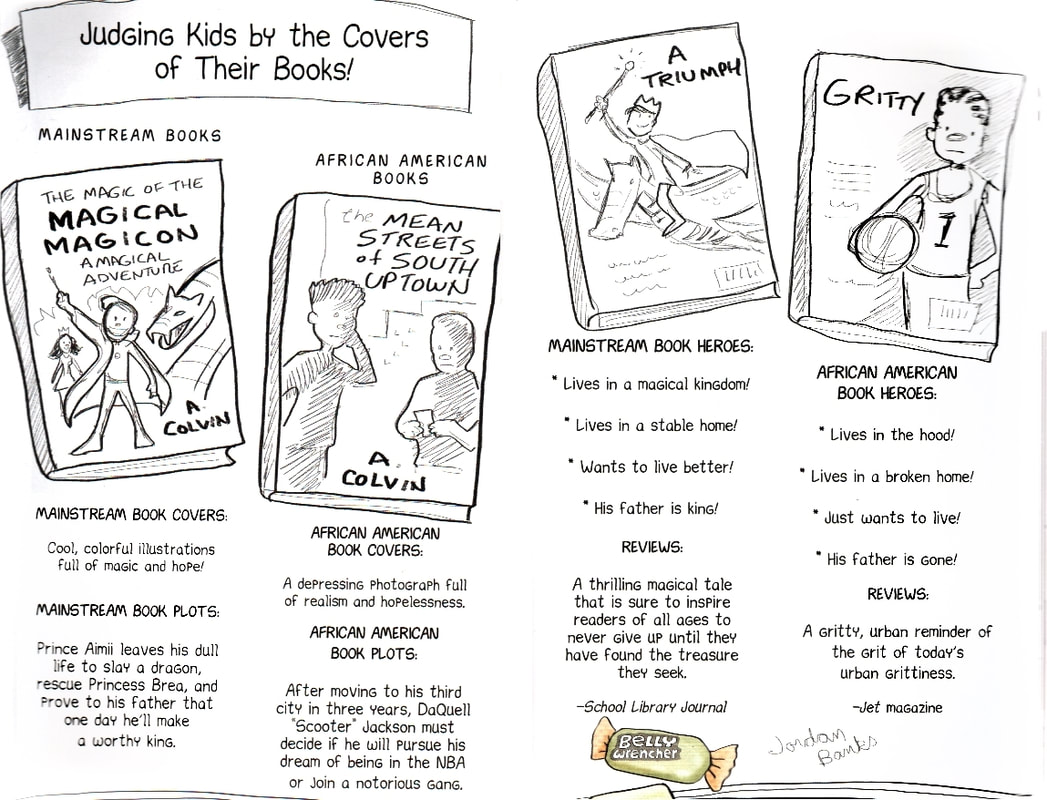

New Kid. By Jerry Craft. Color by Jim Callahan. Harper. ISBN 978-0062691194 (softcover), $12.99; ISBN 978-0062691200 (hardcover), $21.99. 256 pages. A month ago, Jerry Craft’s graphic novel New Kid became the first comic to win the coveted Newbery Medal for children’s literature. I came to New Kid late, and KinderComics readers may remember that I did not include it among my faves of 2019. I wish I had. I confess I put off reading New Kid because I did not love its graphic style, which struck me as cobbled together digitally, with elements seemingly cloned, rescaled, and reused across its pages. At first the work looked patchy to me, compositionally choppy, and too tech-dependent for my tastes. I didn’t see the visual flow or elegance of design that I tend to crave. So, I was closed-mind about this one, I have to say. (This would not be the first time my aesthetic preferences blocked me from recognizing good work. For instance, I recently read Maggie Thrash’s fine comics memoir Honor Girl, done in a seemingly naive watercolor style, and realized that I had been avoiding that one also. I had sold it short.) New Kid deserves better from me. It’s an excellent school story, not only smartly written but visually clever and insinuating throughout. Craft, with exceeding sharpness, depicts African American scholarship boy Jordan Banks and his private school mates at awkward intersections of race, class, and gender. Indeed New Kid, with miraculously high spirits, examines the effects of racism and classism without ever actually breathing those words. Craft is astute and at times can be blunt, but is also endlessly subtle; his touch is marvelously light, yet telling. New Kid manages to be hopeful and often funny, even while acknowledging racism as both systemic feature and stubborn habit. The story of one school year, New Kid gently critiques the class aspirations of private school parents, the casual racist carelessness of teachers, and the blunders of overcompensatory liberal tone-deafness, all while painting Jordan and his fellow students as canny survivors. The book abounds with sly, knowing recognitions, unexplained but pointed, including many gags that show Jordan trying to deal quietly with racial and class-based awkwardness. A middle-class Black boy in a (to him) new school that defines the very notion of privilege, Jordan is alive to the implications of every social move. Craft’s approach is at once realistic, worldly, amused, jaded even, and yet guardedly optimistic; he is properly impatient with ingrained prejudice, yet fatalistically aware that, well, young people have to get on in this broken world. New Kid humorously acknowledges the ways young people of color are too often seen, or rather mis-recognized, and fences smartly with the usual stereotypes about young urban Blackness. The school kids mostly come out well here: they see and deal with social inequality and the willed blindness of adults while upholding their sense of humor and camaraderie. Running gags and droll in-jokes are everywhere: a kind of code and coping mechanism among the kids. For example, Jordan and his classmate Drew call each other mistaken names throughout, mimicking the cluelessness of their white teacher who cannot distinguish one Black student from another. The jokes in New Kid are not just funny, but insightful—as are the young people who tell them. One of the best things in New Kid is a self-reflexive spoof of children’s and young adult publishing that mocks the narrowness of Black depictions in the field. This spread made me laugh out loud (please forgive my crummy scan): If, as Philip Nel argues in Was the Cat in the Hat Black?, the cordoning off of genres marks a de facto line of segregation (Genre Is the New Jim Crow, in Nel’s phrasing), then Craft gets this exactly, and takes the whole publishing field to task. Indeed, the sight of a “gritty” novel for Black teen readers becomes a repeated joke in New Kid, one that stings with its insight but is also downright hilarious. Bravo! This is a supremely wise and charming book that jousts with, and defeats, a thousand cliches.

2 Comments

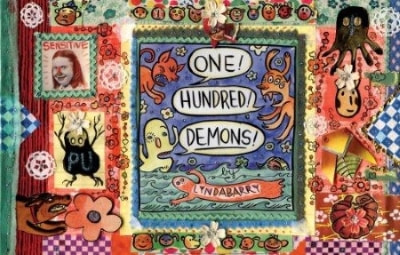

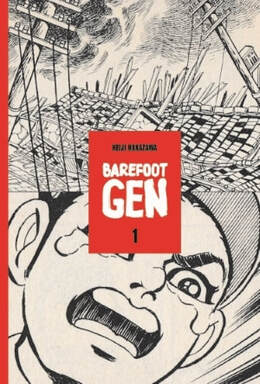

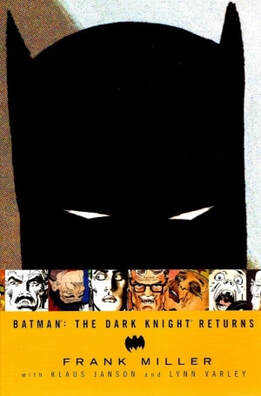

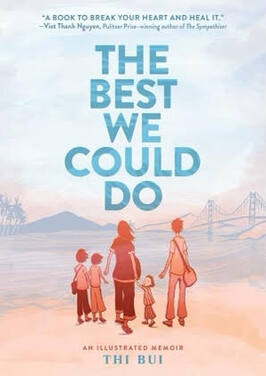

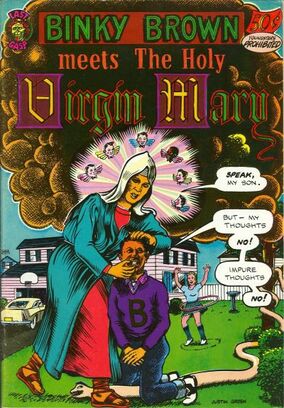

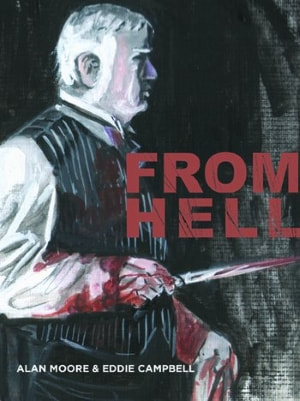

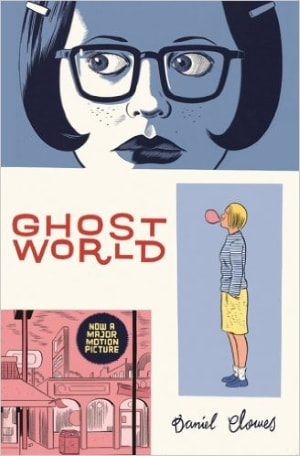

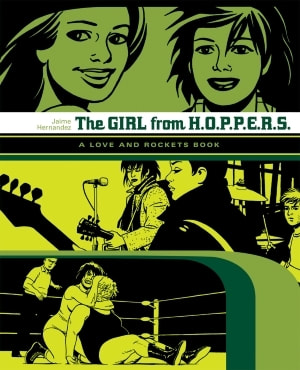

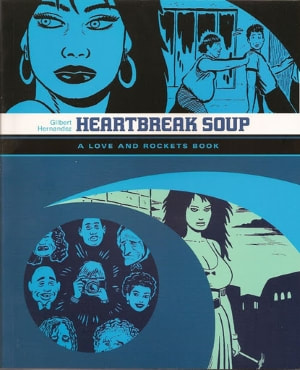

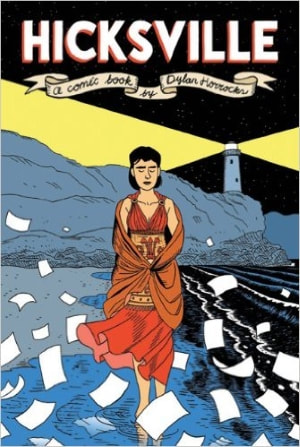

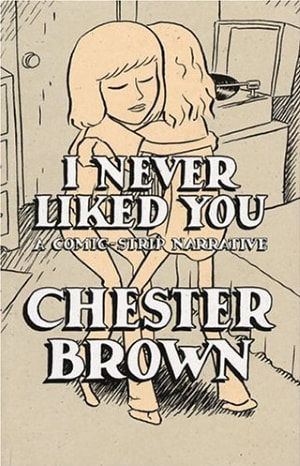

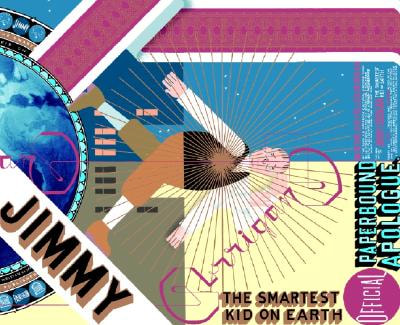

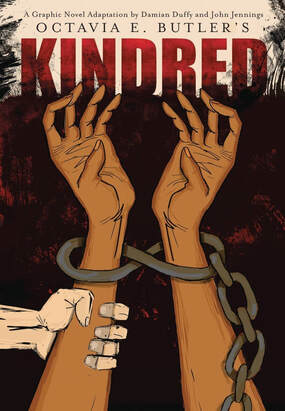

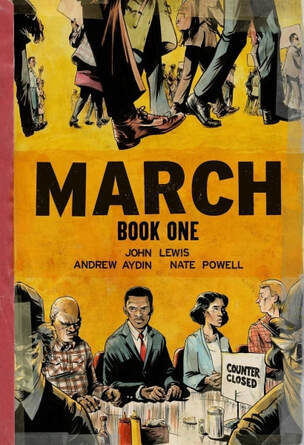

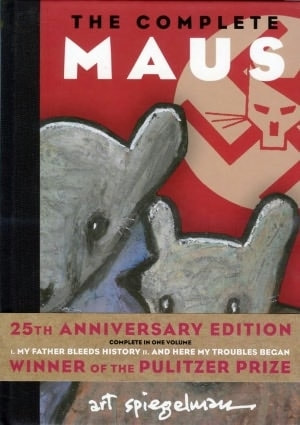

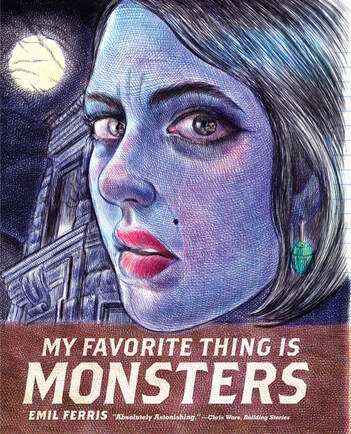

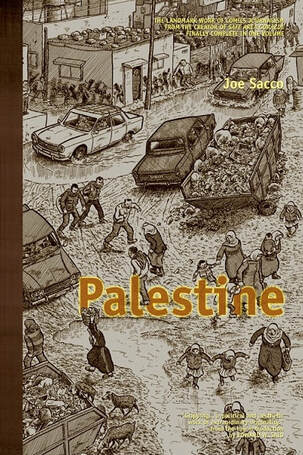

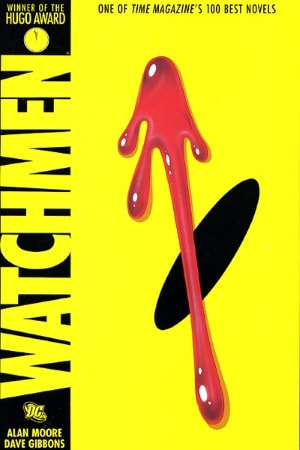

Foreword: As a teacher, I'm often asked to recommend graphic novels, or to explain where the graphic novel genre has "come from." What follows is a list I've used in order to field those questions, one copied, pasted, and adapted from a webpage I've maintained for various classes. Basically, the original aim of this list was to inform students briefly about much talked-about graphic books that we were not covering in class. It was designed to be a changeable document, a resource that could keep shifting and growing, and of course it by no means ever captured all the good and worthy books in the field; it's always been out of date, in fact. Lately I've begun to wonder if this list doesn't need to be drastically revised or perhaps this entire endeavor rethought, but I present it here as, perhaps, a first, rough guide. (Note that this list is not confined to children's and young adult comics.) Below are thirty-three especially noteworthy book-length comics in English. This is not a history of the graphic novel, but a sampling for convenience's sake. In assembling this “cheat sheet,” I've been guided not only by my own taste but also by the amount of scholarship and criticism these works have inspired. For the most part, the books listed here are touchstones for creators and critics; they represent genres or trends that are important in the field, as well as creators who have influenced others. That is, this list consists mostly of landmarks to which other graphic novels are often compared, and which have changed the way we talk about book-length comics. (That said, my own tastes and biases remain a factor, of course.) A bouquet of caveats: This list does not constitute a properly inclusive comics "canon." It is biased toward the self-contained literary graphic novel as practiced in anglophone North America, particularly the US. As such, it neglects a lot of important and delightful stuff — most of the comics world, in fact. I certainly don't claim that these are the only important comics out there, or even that these are the "most" important ones (actually, most great comics IMO are not graphic novels, but that's an argument for another day). Moreover, this list does not capture the present moment, that is, does not represent the range and diversity of comics these days (the newest books here are some three years old). Nor does this list do the important work of advocating for greater inclusivity in comics studies (a principle that informs my syllabi). But if you want to join conversations about the literary graphic novel as currently understood in English-language criticism, this list can give you a head start, a brief breakdown of some keystone titles. Just think of it as one possible point of entry, time-stamped 2020... PS. Clicking on a book's title will take you to an informational page maintained by its publisher. 100 Demons, by Lynda Barry (2002) Barry is one of the greatest writers in comics, and hugely influential. Whether writing, cartooning, or illustrating, she insists on composing everything by hand, and invites her readers into the process of composition — bodily, messy, human. This volume collects strips Barry did for Salon.com, and adds layers of collage and commentary; the result is an evocative storytelling scrapbook. Funny, haunting, troubling, these are memories of childhood and adolescence, transformed into what Barry calls “autobifictionalography.” Gender, culture, growing up, feeling different — all are reflected in Barry’s wonderfully loose, quirky style and intimate voice. An essential book in alternative and feminist comix. Alec: "The Years Have Pants", by Eddie Campbell (2009) Scots cartoonist Campbell found fame in the 1980s British small press with these autobiographical stories, thinly veiled by his use of an alter ego, “Alec MacGarry.” The Alec tales capture Campbell’s relationships and career over a span of decades, with a loose, gestural style and incisive, ironic, sometimes self-damning wit. From love, sex, and family life to Campbell’s take on the ever-changing comics world, these stories evoke the life and times of a brilliant artist and raconteur. They even chronicle Campbell’s work on From Hell (see below). The Years Have Pants gathers thirty years of Alec into one 640-page brick. American Born Chinese, by Gene Luen Yang (2006) This acclaimed and influential book — a key example of the graphic novel for young readers — has an unusual structure consisting of three ostensibly separate stories in different genres: fantasy, sitcom, and realistic, semi-autobiographical fiction. The interaction of these stories yields a whole greater than the sum of its parts, and speaks to issues of divided identity, as hinted by the title. Yang brings it all together unexpectedly, ingeniously, in ways that capture the dilemma of immigrants' children caught between cultures, desperate to transform and “fit in.” His accessible, cartoony, clear-line style evokes idealized childhood, belying the book’s darkness and complexity. The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye, by Sonny Liew (2015) Chan Hock Chye is Singapore’s greatest comics artist, and this book an exhibition of his works, interspersed with his biography, told in comics form. It’s also the history of Singapore itself, from decolonization (i.e. independence from Britain), to its separation from Malaysia, to the present. Here’s the catch: Chan Hock Chye is fictional, while his artistic influences — British, American, Japanese — are real-life landmarks of 20th century comic art. In this tour de force, Malaysian-born Singaporean artist Liew recasts the history of his nation as comics’ history, interweaving fact and fiction and probing the form’s colonial heritage. Provocative, brilliantly executed, mind-boggling. Asterios Polyp, by David Mazzucchelli (2009) This graphic novel by former Daredevil and Batman artist Mazzucchelli shows what can be done when every resource of the medium — layout, drawing style, colors, letterforms, balloons, everything — is deliberately varied to match different characters and shifting points of view. The story concerns architect Asterios — arrogant, out of touch — and his wife Hannah, and how their lives are transformed by circumstance. Mazzucchelli, one of the most electrifying talents in mainstream comic books in the 1980s, retreated from the limelight to explore alternative comics, then spent years crafting this layered masterpiece of form. Almost too clever, but also moving and beautiful. Barefoot Gen, by Keiji Nakazawa (1973-1987; translation completed in 2009) Gen, a semi-autobiographical tale, recounts Nakazawa's life as a survivor of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima — in ten volumes. It's a fierce, emotionally raw, yet deliberately crafted work: an intimate epic. Nakazawa depicts war, more particularly the Bomb, with brutal honesty, unquenchable anger, and a wounded heart. Gen makes a powerful dramatic argument for pacifism and anti-militarism, yet brims with violence, from large scale to small. A furious indictment of imperialism and warmongering (including Japan’s), this is searing, melodramatic, nakedly political storytelling — yet oddly hopeful too. A hugely influential autobiographical comic, and the first book of manga translated into English. Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, by Frank Miller, Klaus Janson, and Lynn Varley (1986) An aged, PTSD-haunted Batman comes out of retirement to save a dystopian Gotham; turns out he’s a righteous lunatic who insists on seeing the world in stark, uncompromising terms. This seminal Bat-story has influenced every Bat-movie and TV show made since the eighties, but it’s really in dialogue with the history of superhero comics and the comic book industry. Brash, brutal, Miller’s story runs roughshod over the DC Universe, bending the genre to personal and satirical purposes. Miller is unafraid to draw ugly to get the kind of intensity he wants — the result is an expressionistic nightmare. Forget the pointless sequels. The Best We Could Do, by Thi Bui (2017) Like several other books here, this memoir inhabits a genre made habitable by Spiegelman's Maus: the multigenerational family memoir woven out of war, atrocity, and trauma, informed by the author’s ambivalence toward her parents. Bui chronicles five generations of her family, first in Vietnam, then the US, all while examining her own resentments, fears, and complex, divided identity. Rigorously self-critical, artfully braided, and beautifully drawn in a fluid, brush-inking style, this book imparts a library’s worth of history, but also subtle, tangled feelings. Though familiar in its approach, it remains tonally and aesthetically distinct. A brilliant, gorgeous, revelatory autobiography. Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary, by Justin Green (1972) Binky stands in for author Green, and this comic recounts Binky/Green’s struggles with religious guilt and what he now recognizes as obsessive-compulsive disorder. An embarrassing, even harrowing memoir that reveals the author’s darkest secrets, this is also a beautifully crafted and hilarious high-water mark in the underground comix movement. It inspired Spiegelman’s Maus and the whole autobiographical comics genre. Weird, disturbing, and poignant, this comic still makes me laugh — and cringe with guilt every time I do. Green’s obsessive renderings, imaginative flights, and ironic humor about his own struggles have influenced comics ever since. Not for the fainthearted, but great. Blankets, by Craig Thompson (2003) Inspired by French artists, Thompson has a voluptuous, sensual style that carries readers away. Blankets is his breakout book, a memoir of adolescence, sexual awakening, and strict religious upbringing. Some readers find the heart of the book in its depictions of love and longing; I find it in Thompson’s rebellion against fundamentalism. This is not a memoir in the same vein as Green’s Binky; its images are more beautiful, its perspective less ironic, more Romantic, for some readers even mawkish. But read it to see how graphic memoir has been mainstreamed, and for a lovely example of the book as art object. Bone, by Jeff Smith (2004) Originally self-published, then republished by Scholastic, and now translated worldwide, Bone is a 1300-page epic (serialized over thirteen years). Smith has described it as Looney Tunes meets The Lord of the Rings, and his animation background comes out in the work, which combines Disneyesque charm and childlike heroes with unexpected depths. Smith’s style, influenced by Walt Kelly (Pogo), mixes slapstick cartooning with elegant brushwork and lush landscapes. His comic timing is terrific. The usual tropes of fantasy are here (princesses, dragons, dark lord, prophecy), but freshly redone for comics. Smith’s influence, particularly on children’s comics, would be hard to overstate. Building Stories, by Chris Ware (2012) The formalist comics achievement of the 21st century, so far? Depending on your POV, Building Stories either perfectly fulfills or violates the notion of “graphic novels.” It consists of a large box that recalls board games like Monopoly but contains fourteen different “Books, Booklets, Magazines, Newspapers, and Pamphlets” that can be read in any order (I don’t know any two readers who’ve read it the same way). The drama — poignant, sometimes heartbreaking — centers on a Chicago apartment building and a lonely, unnamed woman as she grows up and has a family. Ware captures sensations I never expected comics to capture. A Contract with God, by Will Eisner (1978) Veteran artist Eisner, a comics pioneer since the 1930s, launched his career’s last great phase with this “graphic novel” — actually four short stories about working-class Jewish lives, rooted in a common locale, a Bronx neighborhood remembered from Eisner’s youth. These stories mix social realism and melodrama. Here Eisner put his mature style — loose, rumpled, gritty — to new use, adopting a literary aesthetic and book format that lent legitimacy to the emerging graphic novel genre. Most impressive is the semi-autobiographical title story, a fable inspired by the death of Eisner’s daughter. Often wrongly called the “first” graphic novel, yet still seminal. Epileptic, by David B. (1996-2003, complete English trans. 2005) Another memoir whose brutal candor recalls Maus, Epileptic recounts the author’s family’s struggle to heal his brother’s severe epilepsy, which gradually isolates the brother and chokes off any chance of autonomous living. The family seeks cures in pseudoscience and mysticism, but is thwarted time and again, and haunted by its powerlessness. Concurrently, the book unfolds a history of postwar France, and 20th century atrocities generally, as the author-protagonist processes the world through a filter of rage and his art fearfully evokes an epileptic’s loss of control. Dark, hallucinatory, symbolically dense, swirling with hypnotic detail—a troubling masterpiece of graphic expressionism. From Hell, by Alan Moore & Eddie Campbell (1999) A fair candidate for Moore’s “other” great graphic novel (after Watchmen): a dense, paranoid retelling of the “Jack the Ripper” killings in London circa 1888, here treated as part of an occult conspiracy and an indictment of Victorian misogyny and classism. This project took a decade to complete, and shows not only Moore’s obsessiveness but also artist Campbell’s sense of period. Architecture, medicine, politics, freemasonry — it all gets caught up in their web. Campbell’s inky, scratchy, black-on-white pages, influenced by penny dreadfuls, are far from Watchmen's slickness. Magisterial, sinister, frightening, with alarming violence and butchery, and brutal commentary on gender. Fun Home, by Alison Bechdel (2006) Bechdel, known for her strip Dykes to Watch Out for, shifted gears with this memoir, which quickly became one of the US’s most-analyzed comics. Fun Home explores the relationship between Alison (an out lesbian) and her father Bruce (gay, closeted), whose death shortly after her coming-out may have been a suicide. The learned Bechdels often communicated through reading and writing rather than face to face, so Fun Home deploys myriad literary references (Joyce, Proust, Wilde, Colette, Fitzgerald) to weave an ambivalent portrait — precise, detailed, self-reflexive, darkly funny — of a complex, difficult man. After Maus, the most academically influential graphic book. Ghost World, by Daniel Clowes (1997) Drawn from Clowes’s comic book Eightball, Ghost World epitomizes mid-nineties alternative comics. A fiction with veiled autobiographical elements, it tracks the relationship between two young women, Enid and Becky, and what happens when they discover that their hip air of contempt for the world is not enough to carry them over the threshold to adulthood. Clowes’s satirical, deadpan humor runs throughout — the book is at times hilarious — but is matched by tacit emotional undercurrents. Beneath a chill, almost antiseptic style (emphasized by cold blue-green shading), Ghost World hints at psychological unease and turmoil, and ultimately tells a moving coming-of-age story. The Girl from H.O.P.P.E.R.S., by Jaime Hernandez (2007) The Hernandez brothers’ Love and Rockets (1981-) is arguably the most groundbreaking US comic book series of the past forty years. It defined alternative comics with its diverse cast, Latina/o and LGBTQ characters, punk rock/DIY ethos, mixture of underground and mainstream aesthetics, and experiments in form. Jaime’s “Locas” serial, based in Hoppers, a barrio inspired by his childhood in Oxnard, follows the lives and loves of Maggie Chascarillo and her circle, and is still going strong today. This volume captures Jaime’s amazing artistic growth in the mid-eighties, and boasts fluent, elegant cartooning, vivid, indelible characters, and searching, deeply moving stories. Heartbreak Soup, by Gilbert Hernandez (2007) While Jaime Hernandez was doing “Locas,” brother Gilbert created the other acclaimed serial in Love and Rockets: the stories of Palomar, a mythical Central American village populated by families, friends, lovers, and rivals. Gilbert’s style, broader and more grotesque than Jaime’s elegant naturalism, perfectly fits this magic-realist chronicle of love, loss, jealousy, psychological trauma, and social and political upheaval. This is bold work, exploring queer identities and sexualities, fearlessly depicting childhood and the traumas of growing up, and reflecting on art’s role in the world. This volume collects an extraordinary mid-80s run that shows Gilbert growing by leaps and bounds. Hicksville, by Dylan Horrocks (1998) Hicksville is a bucolic New Zealand town where everyone lives and breathes comics: a utopia for comics lovers. But what happens when a journalist comes to town determined to unearth the secret of a millionaire artist from Hicksville, a hometown boy turned pariah? Horrocks’ love letter to comic art is also a lament for the history of the comics business, one that has treated its artists like dirt. This funny yet melancholy meta-comic epitomizes alternative comics, and reflects on artistry-versus-commerce, the very nature of the comics form, and New Zealand's colonial history. Brilliantly cartooned: crisp yet scruffy, lively, organic. I Never Liked You, by Chester Brown (1994) A guilt-haunted memoir of adolescence, this book treats the ordinary stuff of high school relationships with a seriousness and graphic austerity that make it emotionally wrenching. Chester, a severely repressed young man, cannot seem to perform masculinity in the expected way, and his social relationships are punctuated by moments of almost-autistic withdrawal. His relationship with his mother is particularly fraught, and leads to a shattering climax. Beautifully drawn, with a fragile, minimalist line and dreamlike emotional reserve. A seminal example of graphic memoir from early-nineties comic books, and a key work of Canadian alternative comics from a restless, controversial creator. Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth, by Chris Ware (2000) Ware may be the most acclaimed cartoonist of the 21st century. He is famed for his command of, and willingness to push, the comics form; his dense, blueprint-like pages; his unerring, diagram-like style; the bleak honesty of his stories; and his focus on sad, isolated characters. He is comics’ poet laureate of loneliness. Some find Ware’s work unlovable, but others find in it a poignancy that few comics have reached. Jimmy Corrigan, his breakout novel, is a multi-generational chronicle of the screwed-up Corrigan family, and a devastating portrayal of failed, self-deluding White masculinity. Quiet, heartrending, epic, anticipating Ware's Building Stories. Kindred, by Damian Duffy and John Jennings (2017) Octavia Butler’s time-travel novel Kindred (1979) transports a modern African American woman to Maryland in the early 1800s, during slavery’s reign, where she must try to save the lives of her ancestors, both Black and White. Butler evokes the culture and psychology of slavery with horrific clarity. Duffy and Jennings wrestle with this challenging classic in an adaptation that favors frenzied expressionism over naturalistic detail, while seeking to preserve the original’s pacing and depth. The results show signs of struggle and inspiration, and intense feeling. A watershed in the contemporary Black comics movement, this has opened doors to new work. March, by John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell (three volumes, 2013-2016) Adapted from the memoirs of Civil Rights activist John Lewis (Freedom Rider, onetime chair of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and longtime Congressman), this trilogy is a testament: a personal window onto a history at once traumatic and exhilarating. While unfolding Lewis’s personal story, the book shows, clearly and unblinkingly, the politics and process of nonviolent Civil Rights protest. Powell’s organic drawing sets the rhythms, conjures a full, believable world, and brings the pages to life with an assured naturalism and graphic fluency that recall (without mimicking) Will Eisner. An autobiographical American epic, and an eye-opening work of comics historiography. Maus, by Art Spiegelman (two volumes, 1986 and 1991) Maus evokes the Holocaust from one survivor’s perspective—and that of his son, cartoonist Spiegelman, who works to get his father’s memories down on paper. It contains stories inside of stories, tracing the Shoah from prewar Poland to its still-traumatic aftereffects today, all while exploring the antagonism between father and son. Oddly, it exploits the so-called funny animal tradition: Jewish people appear as mice, Nazis as cats: a startling, sacrilegious device. Academically and critically, Maus has become America’s most talked-about book of comics ever: a generative project that inspired other books on this list. Its influence is hard to overstate. My Favorite Thing Is Monsters, by Emil Ferris (2017) Karen, a lonesome queer girl who envisions herself as a monster, investigates the death of an neighbor in her Chicago apartment building. That neighbor turns out to have been a Holocaust survivor with a knotted, complicated past. Karen's detective work brings her to dark places, and Ferris renders her quest in stunning art, lovingly detailed, obsessively dense, drawn almost entirely with a ballpoint pen in a series of spiral school notebooks (Karen's journals). Atmospheric, laced with references to high art and monster movies, suspenseful, and affecting, this staggering book does things with a comics page that I hadn’t seen before. Palestine, by Joe Sacco (1996) Journalist Joe Sacco makes comics about war zones and contested places in the world: Bosnia, Chechnya, the Middle East. These comics draw from his travels and investigative reporting. Influenced by underground comix, Sacco at first favored satire and grotesque exaggeration, but with Palestine, his foray into the Occupied Territories, he began shifting toward hyper-detailed realism, as he pursued his subjects with greater journalistic seriousness. Palestine advocates the Palestinian cause, giving an unabashedly political, while also scrupulous, unflinching, and human, perspective on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Sacco’s work has earned praise as both reportage and literature and fueled the graphic journalism movement. Persepolis, by Marjane Satrapi (2000-2003, English trans. 2003-2004) Persepolis, an Iranian autobiography first published in France, joins Maus and Fun Home as one of the most acclaimed graphic memoirs. Satrapi, born into a progressive Persian family, grew up during the Iranian Revolution and ensuing Iran-Iraq War. Her family, opposed to the Shah, welcomed revolution, but found the new fundamentalist regime even more oppressive. Satrapi left Iran for France. Using a stark, pared-down style, and an ironic voice that filters politics and violence through a child’s perspective, Persepolis explores traumatic memories and the bitterness of exile, while countering anti-Iranian stereotypes. Widely translated; adapted to film (2007) by Satrapi herself. Smile, by Raina Telgemeier (2010) Telgemeier, America’s best-selling graphic novelist, has legions of readers, especially girls aged 8 to 12. In 2019, her new graphic novel Guts (her ninth) got a million-copy print run. She started in self-published minicomics, but hit big with Scholastic, for whom she adapted four of Ann Martin’s Baby-sitters Club novels (2006-2008) before undertaking original GNs, starting with this memoir of girlhood, growth, and, um, dentistry. Phenomenally successful, Smile opened the door to further books by Telgemeier, both autobiographical (Sisters, 2014; Guts) and fictional (Drama, 2012; Ghosts, 2016). Accessible, energetic, crystal-clear, her work has become THE template for middle-grade GNs. Soldier's Heart, by Carol Tyler (2015) First published as a trilogy titled You’ll Never Know (2009-2012), Soldier’s Heart is now available in a single, revised volume. It tells the story of WW2 veteran Chuck Tyler and of his daughter Carol’s efforts to understand the War’s impact on his psyche. Working in the tradition of Maus, this intergenerational memoir digs into repressed wartime memories in order to understand and pay homage to a distant, sometimes irascible man whose hard exterior hides the aftereffects of trauma. Exquisitely illustrated in flowing, textured drawings and ravishing washes of color, this is a gorgeous, moving, heartfelt exploration of family (and) history. This One Summer, by Mariko Tamaki and Jillian Tamaki (2014) In this acclaimed Young Adult graphic novel, a girl, Rose, spends summer at the beach with her parents and her friend Windy. Rose’s mother, depressed, bears a secret that weighs on the family, Rose’s parents are at odds, and Rose blames her mom for the conflict. Windy and her family provide contrast. Rose, seeing through eyes clouded with mistrust and jealousy, tries to understand what’s expected of her as a woman, and what’s wrong with mom. A subtle exploration of girlhood and gender expectations, poetic in its rhythms and imagery. Transporting, haunting, a benchmark for its genre, though often unfairly maligned as "not for children." Understanding Comics, by Scott McCloud (1993) A book of theory presented in comics form, Understanding Comics may be the most-cited textbook in the field — but no textbook should be this much fun to read. Using his own cartooning as evidence, McCloud strives to build a grand theory that encompasses nearly everything about comic form: drawing style, breakdown/transitions, image/text interplay, line, color, on and on. It’s a terrific, insanely ambitious performance, one that has influenced comics studies ever since. To be honest, it changed my life, though nowadays I find myself arguing with it! The best candidate for a “primer” in comics studies. (We'll sample in class.) Watchmen, by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons (1987)

This most acclaimed of superhero comics asks, what would superheroes be like in the real world? Set in an alternate 1985, it’s a dystopian philosophical novel about the Cold War, empire, surveillance, paranoia, and fate. Obsessively detailed, Watchmen epitomizes the idea of the graphic novel as a system: dense, complex, full of echoes. Gibbons’s meticulous art perfectly captures scriptwriter Moore’s thirst for order. This book persuaded many that a superhero story could be Literature. (Forget the comic book spinoffs and movie, and take the 2019 TV series on its own terms; Watchmen’s meaning resides in its readability and book form.) |

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed