|

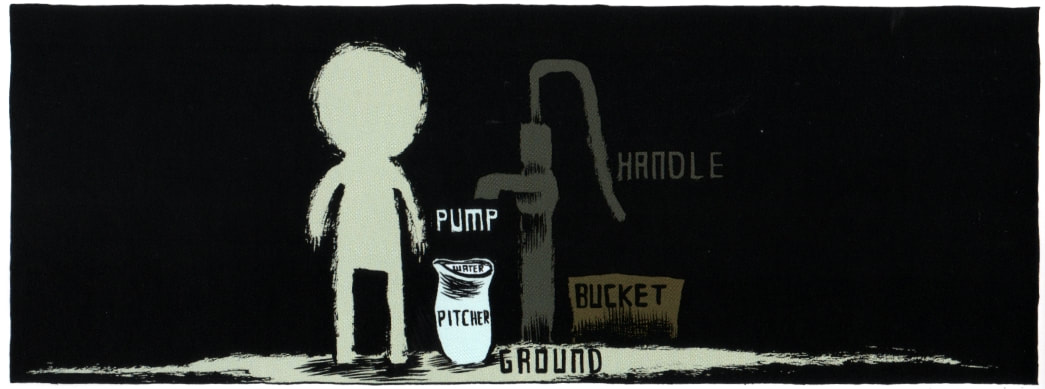

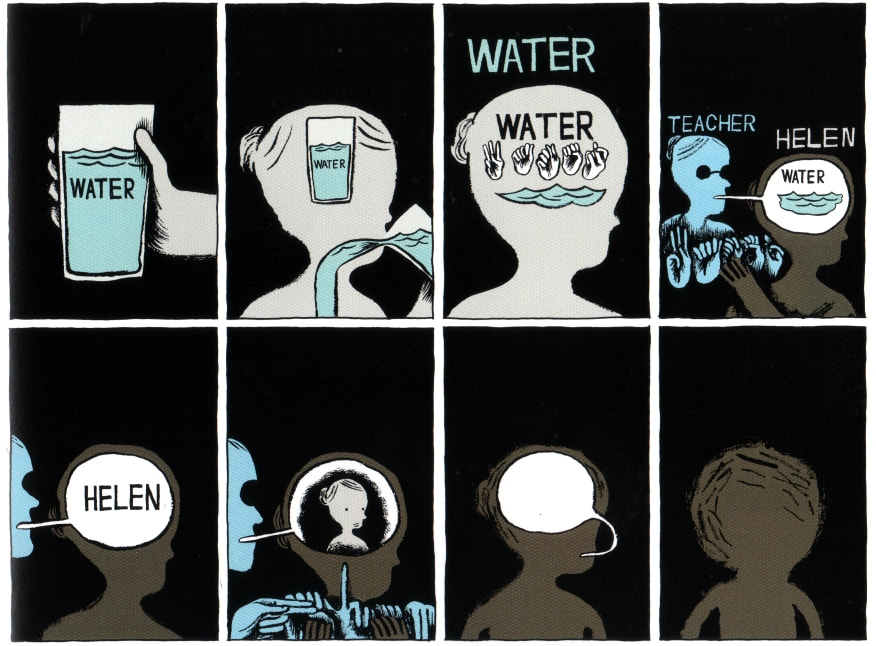

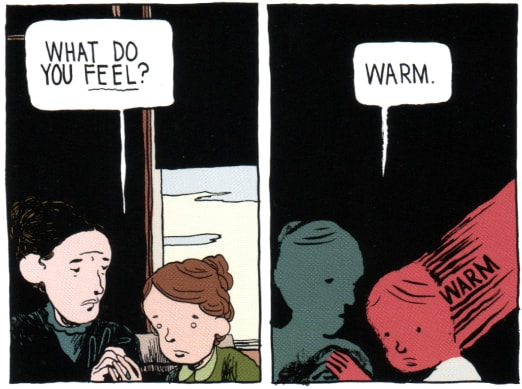

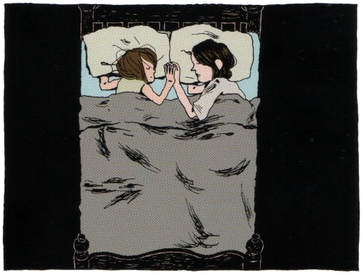

Annie Sullivan and the Trials of Helen Keller. By Joseph Lambert. Edited by Jason Lutes. Disney/ Hyperion, 2012. ISBN 978-1423113362. $17.99, 96 pages. Winner of the Will Eisner Award for Best Reality-Based Work, 2013. I have a dozen copies of Joseph Lambert's Annie Sullivan and the Trials of Helen Keller in my office. It's that good. I bought most of those copies through Alibris just over a year ago while preparing to teach my grad seminar "Disability in Comics." I had always intended Annie Sullivan to be a required book in that class, along with such other comics as Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary, The Spiral Cage, Epileptic, El Deafo, and Hawkeye: Rio Bravo. In fact Annie, along with José Alaniz's Death, Disability, and the Superhero, was one of the books that inspired me to teach the class in the first place. When I discovered that Annie was out of print, I lost my mind a bit, but then decided to scrounge up multiple used copies on my own dime and turn my office into a lending library. So, I ended up with a lot of Annie, and loaned out copies for several weeks. It's criminal that this modern classic is out of print – and I hope someone does something to change that soon. Annie Sullivan is part of a series of comics biographies packaged by the Center for Cartoon Studies for publisher Disney/Hyperion (2007-2012). These include books on Harry Houdini, Satchel Paige, Amelia Earhart, and Henry David Thoreau. All the books are hardcovers that run about 100 pages, and all are good; John Porcellino's Thoreau at Walden is wonderful. But Lambert's book, I believe, is one for the ages. Why do I admire this book so much? Lambert, whose work I came to know through The Best American Comics 2008 (edited by Lynda Barry) and then his story collection I Will Bite You! (2011), is simply a great cartoonist. His work displays a patience for careful breakdowns and repetition which approaches that of Harvey Kurtzman or of a top-notch humor strip artist. His drawing is simplified in appearance but also nuanced and emotionally precise, capable of capturing crucial subtleties of gesture and expression. Further, he has an appetite for expressing feeling and sensation through variations in traditional form; he can make a regular, unvarying grid seem musical and powerful. Feeling and sensation are the life's blood of Annie Sullivan, a book that works cannily, in an austere, rhythmically controlled way, to convey how its title characters experience the world in spite of (or through the filter of) isolating sensory impairments. Lambert does this with a poet's command of meter and a true biographer's interpretive sensitivity. One of the things Annie Sullivan does so well is inevitably, perhaps cruelly, ironic: it finds ways to visually convey non-visual experience, particularly haptic experience: the experience of handling things, of placing your hand in someone else's, of spelling things out with your fingers, and so on. Annie Sullivan taught Helen Keller, who lost her sight and hearing before she turned two, to recognize things in the world with her hands, and to communicate through finger spelling. Keller wrote in her autobiography, The Story of My Life (1903), that her tutor Sullivan revealed to her "the mystery of language," a gift that, she said, "awakened my soul, gave it light, hope, joy, set it free!" Lambert does a stunningly smart job of communicating both how Sullivan taught Keller and how hard it was. His pages convey Helen's haptic world and her opening-out into written language, using a range of techniques: tight, inescapable grids; nearly all-black panels and stark contrasts of light and darkness; isolated and stylized figures; systematic color-coding of figures and objects; inventive rendering and placement of single words; and stylized iconic hands to represent finger spelling. Formally ingenious, these techniques are also moving, for they show the extent of Helen's isolation, the intense, mutually dependent relationship between Helen and Annie, and the cascading emotional consequences of Helen's growing literacy. In a profound sense, Lambert's book is about obstacles to communication, and how, in the singular Hellen/Annie relationship, these were overleapt. Again, to render haptic experience visually is unavoidably ironic. In my class we discussed not only the formalistic means but also the ethics of this approach, in comparison and contrast to other comics' visual depictions of non-visual experience (particularly Marvel's Daredevil). Annie Sullivan and the Trials of Helen Keller cannot perfectly convey Helen's phenomenal world. It cannot help but be an ocularcentric evocation of sightless experience. That's a problem. Yet the book is a highwater mark in the synesthetic use of comics' visual form to suggest life beyond the visual; in this, it strikes me as both ingenious and sensitive. Another thing that makes Annie Sullivan so strong is its dual focus on teacher and student. Sullivan comes off, not as some beneficent "miracle worker," but as a conflicted, heroically stubborn, frank, fierce, and deeply sorrowful person, shaped by her own visual impairment, her wretched years spent living in an almshouse, the tragic loss of her brother, and her just resentment of gender convention and the straitened roles available to women in 19th century America. Sullivan appears to have been a difficult and marvelous person, sometimes bitterly acerbic, and moved by abiding grief and anger. At times Lambert depicts her teaching of Helen as autocratic, harsh, even borderline abusive. Yet he also shows how and why it worked. Lambert, that is, portrays Annie with great empathy but also unsentimental candor. The book is tough-minded, sketching in the horrors of Annie's early life discreetly but powerfully and showing her resistance to the men and women who sought to control her. What's more, in its depiction of teacher and student together, Annie Sullivan avoids the triumphal cliches of children's biography. While Lambert rightly depicts Sullivan's breakthrough with her pupil as remarkable (the famous scene at the water pump, recounted in Keller's biography and in the many versions of The Miracle Worker), that is not the end of the story, and the book's second half delves into other "trials." Chief among these is an accusation of plagiarism that hurt Keller deeply, bedeviled her early efforts as a writer, and estranged Keller and Sullivan from their benefactors in the field of education for the visually impaired. In the end, what emerges is not a simple story of Helen's triumph over adversity but a complex sense of Helen and Annie's profound dependence on one another. In fact, the conclusion of the book is oddly melancholy, offering none of the facile reassurances that ableist stories of overcoming disability tend to offer. In sum, Annie Sullivan is a brilliant feat of writing as well as cartooning and design. It really is a shame that Annie Sullivan and the Trials of Helen Keller is out of print. I can't say that enough.  UPDATE: It's back in print! As of October 2018. Yes!

0 Comments

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed