|

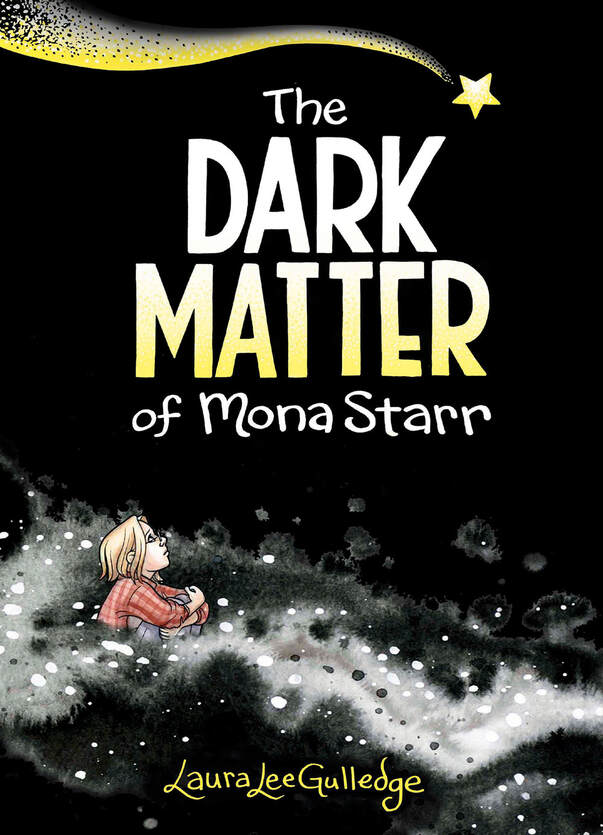

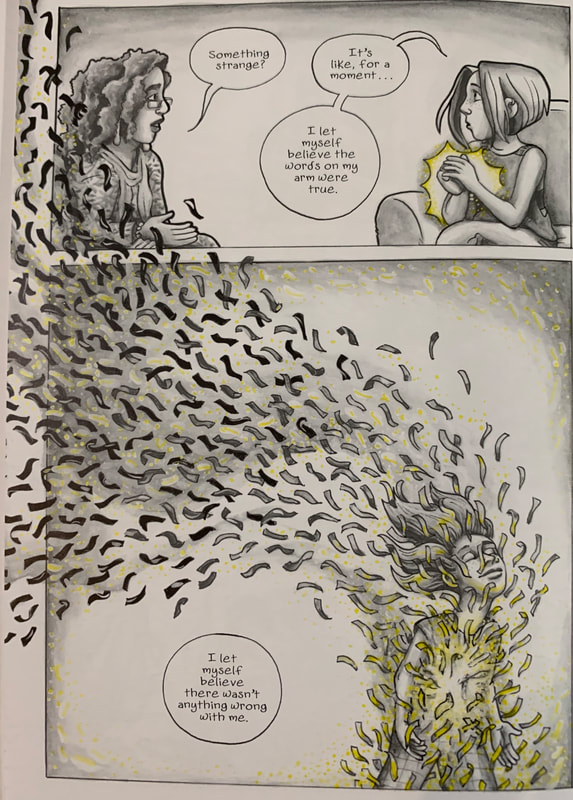

The Dark Matter of Mona Starr. By Laura Lee Gulledge. Amulet Books/ABRAMS, 2020. ISBN 978-1419742002, $US14.99. 192 pages. In this semi-autobiographical novel, Mona, a high-schooler and artist who suffers from depression, undertakes a self-study to better understand her needs and triggers and fashion a "self-care plan." Though a loner by temperament, she learns to think outside of herself and recognize loving relationships and creative collaboration as important resources in her life. With the help of her counselor, parents, and friends, Mona chooses an ethic of community and participation, sharing her aesthetic gifts and inspiring others to do the same. Looking beyond herself, even as she honors her own needs, enables her to engage the world on different terms and, to some degree, counteract her depression. The novel climaxes with a community art project in which Mona and her self-styled "Artners," Aishah and Hailey, invite many of their fellow high-schoolers to collaborate in a spirit of loving community. The story's keynotes are self-love, self-advocacy, and willful optimism, and its last word (literally) is hope. Like Ellen Forney's celebrated memoir Marbles, this novel hovers between raw personal storytelling and hortatory self-help, with chapter headers that give emphatic advice, such as Turn emotion into action and Break your cycles. Author Gulledge shares her own self-care plan in the back pages, and her notes confirm that Mona Starr is indeed based on her. Artistically, the book is wildly expressive; the pages brim with visual metaphors of depression and elation, self-isolation and self-release, artistic engagement and pure joy. Depression, Mona's so-called dark matter (her mom is an astrophysicist), appears as swirling black clouds, faceless anthropomorphic demons, dark waters, black flames, and gripping hands. Moments of self-realization and delight are accompanied by stars and streaks of bright yellow: the one spot color in Gulledge's otherwise black-and-white, or rather grayscale, aesthetic. Mental landscapes — vast oceans, deep, dark wells, and the swirling cosmos — convey Mona's ever-shifting inner state. Consensus "reality" is perfused with expressionistic symbolism, and many pages leave behind real-world settings altogether. The sheer profusion of visual symbols reminds me of, say, Iasmin Omar Ata's Mis(h)adra (a semi-autobiographical account of epilepsy that is likewise braided with graphic devices signaling the protagonist's inner state). Gulledge's figures, word balloons, and symbols routinely break out of her panel grid — in fact, there is not one page that obeys a strict, unbroken paneling — and the layouts are ceaselessly dynamic. Immersive full bleeds are frequent. In short, the book is a staggering exercise in expressive drawing and page-making. Story-wise, though, Mona Starr feels a bit thin and undeveloped to me. Despite hints that other characters may also struggle with mental illness or disability, and despite the plot's emphasis on seeking "help" and community, the novel feels very much absorbed by Mona's mental state and Gulledge's exhortations to embrace one's creativity. The book feels idealized, dreamy, and self-involved; Gulledge's artistic bravura, the sheer busyness of her pages, doesn't let the depression seem real. Everything is couched in terms of artistic therapy, self-study, and a self-improvement "project." Mona's counselor is introduced at the start, before Mona's depression has manifested narratively, and the greater context is emphatically reassuring. Much of the book consists of poetic self-reflection, heightened by the overflow of visual metaphor, as if in confirmation of Mona's creative "genius" (a personality test labels her "the potentially unstable visionary type"). Familial and social complexity take second place to exploring Mona's state of mind through ravishing visuals. The singular focus on Mona's feelings and self-conception would probably be smothering in bare prose; only Gulledge's ecstatic imagery gives the story life and depth. The result is heady and interesting but, I'm tempted to say, less novelistic than an exercise in didactic self-help. Somehow, the book manages to be at once lyrical, spectacular, and a confidently crafted exercise in comics, yet also frustratingly under-done, as if Gulledge couldn't quite take distance from what is, after all, a kind of exhortative autofiction. But here's the deal: I enjoyed reading Mona Starr, and it has moments that, on re-reading, still get me choked up. The book's conclusion is calming and gratifying, and I cannot deny Gulledge's hard-won insight. I am pretty sure that some readers will be affirmed, and perhaps even forever changed, by reading this book. I wouldn't recommend Mona Starr for complex, intersubjective storytelling, but will remember its powerful evocations of feelings and states of mind, as well as Gulledge's confident artistry.

0 Comments

A partial list, forever in progress (every week I learn about new stuff)!(This Election Week post grew out of queries from colleagues as well as virtual teach-ins at CSU Northridge. It is very much a quick, tentative dispatch!) Below is a bunch of notes, roughly organized, about comics (especially graphic novels) that engage urgent social issues such as voting, migrant and refugee experience, racism, police violence, political activism, gender, feminism, and LGBTQ+ activism. Note that not all of these books are designated as children's or young adult books, and many contain frankly adult content. OTOH, there are some excellent young reader's books here. Besides long-form comics like graphic novels, other, shorter comics may engage such issues too, webcomics in particular. Webcomics are typically free and often address vital issues briefly and powerfully; e.g., consider the many affecting comics about living under COVID (see especially the series “In/Vulnerable,” on thenib.com, researched by reporters for The Center for Investigative Reporting and drawn by Thi Bui: https://thenib.com/in-vulnerable/). The Movement for Black Lives and the Black Comics Explosion  March, by the late John Lewis, with collaborators Andrew Aydin and Nate Powell — a memoir trilogy about Lewis’s participation in the Civil Rights Movement. One of the most acclaimed of recent American comics, and highly recommended. “Your Black Friend,” by Ben Passmore, a short satirical comic found in his book Your Black Friend and Other Strangers. Also, see Passmore’s collaboration with Ezra Claytan Daniels, BTTM FDRS, an urban horror story and satire about gentrification—it’s gross and very good! (I’d check out anything by Passmore, though he may not appeal to everyone, and some of his more underground-like work is a mixed bag. He has a new graphic novel called Sports Is Hell that I haven’t read yet. Be sure to look for Passmore’s online comics, especially on The Nib. He often engages issues of police violence and critically engages the BLM movement.) Damian Duffy and John Jennings adapted Octavia Butler’s classic novel Kindred into a graphic novel: a heartfelt piece of work about time-traveling back into the era of slavery. They have recently adapted another of Butler’s novels, Parable of the Sower, but I haven’t read it yet. Speaking of Jennings, he and fellow artist Stacey Robinson together drew the graphic novel I Am Alphonso Jones, written by Tony Medina—the story of a young Black man killed by police. This is often categorized as YA. Hot Comb, by Ebony Flowers, combines memoir and fiction: a series of short, intimate stories, many exploring the consequences of racist beauty standards for Black women. Understated, powerful. Sometimes also categorized as YA. See Jerry Craft’s New Kid for a funny, insightful middle-grade GN about being a scholarship kid of color in a tony private school. (Craft has a new book, Class Act, that I haven’t read yet.) Bitter Root, by Chuck Brown, David Walker, and Sanford Greene, is an ongoing comic book series that filters period pulp action through African American historical and cultural lenses. There are two collected volumes so far. It’s overtly political even as it dishes out monster-smashing action: an Ethno-Gothic, steampunk, antiracist adventure. Cool. (Not understated!) Great African American SF/fantasy novelists like Nalo Hopkinson, Nnedi Okorafor, and N.K. Jemisin have been writing superhero comic book serials lately. Jemisin is about 2/3 of the way through a Green Lantern series with many topical elements titled Far Sector, drawn by Jamal Campbell. It concerns race and the challenge of living in a pluralistic society (a faraway world inhabited by billions of beings of several different species). Smart, rich work. Immigrant and Refugee Experience Alberto Ledesma shares reflections from his life as an undocumented immigrant in Diary of a Reluctant Dreamer, a very personal scrapbook of sorts that grew out of a series of Facebook posts. Eye-opening for me, and poignant. Besides superheroes, Nnedi Okorafor has written a SF comic called LaGuardia that deals with immigration and nativist backlash—but on a planetary level! It’s drawn by Tana Ford. Escaping Wars and Waves, by graphic journalist Olivier Kugler, depicts Syrian refugees living in refugee camps, and is excellent. Border: A Crisis in Graphic Detail, edited by Mauricio Alberto Cordero, is a recent comics anthology about migrant experience at the US’s southern border, and a fundraiser for the South Texas Human Rights Center. Powerful stories and testimony. The Scar, by Andrea Ferraris and Renato Chiocca, is a brief but powerful treatment of the US/Mexico border. Migrant: Stories of Hope and Resilience, written by Jeffry Korgan and illustrated by Kevin Pyle, recounts personal stories of crossing the US border (I haven’t had a chance to read it yet). Thi Bui’s graphic memoir, The Best We Could Do, about five generations in the life of a Vietnamese American family, is brilliant, a great book. (Matt Huynh’s webcomic Cabramatta resonates with this: http://believermag.com/cabramatta/. So does GB Tran's book Vietnamerica.) The recent YA graphic memoir by Robin Ha, Almost American Girl, depicts a Korean American experience that perhaps invites comparison. There are quite a few graphic memoirs about the experience of immigrants’ children—see, e.g., I Was Their American Dream, by Malaka Gharib. They Called Us Enemy, by George Takei, Justin Eisinger, Steven Scott, and Harmony Becker, is an autobiographical account of the incarceration of Japanese Americans during WW2. Much to learn here. Immigration policy is discussed in Open Borders: The Science and Ethics of Immigration, by Bryan Caplan and Zack Weinersmith, though I haven’t gotten to read it yet. It’s a didactic graphic book: less story than argument. But there are many great comics like that! Comics on the Political ProcessUnfit: How to Fix Our Broken Democracy, by Daniel Newman and George O’Connor—though I’m afraid I haven’t read this yet. Drawing the Vote: An Illustrated Guide to Voting in America, by Tommy Jenkins and Kati Lacker. Comics about Indigenous LivesFor comics by Indigenous creators, see for example the anthology Moonshot, and check out publisher Native Realities: https://redplanetbooksncomics.com/collections/native-realities. In particular, the collaborations of artist Weshoyot Alvitre and writer Lee Francis IV (e.g., Sixkiller; Ghost River: The Fall and Rise of the Conestoga) have captured my attention. Look also for the anthology Deer Woman, co-edited by Alvitre and Elizabeth LaPensée. A recent scholarly collection, Graphic Indigeneity, ed. Aldama, will help here. Celebrated comics journalist Joe Sacco (who produces one stunning book after another) has just recently published Paying the Land, a book about resource extraction and energy politics, but most particularly the history of an Indigenous Canadian people, the Dene. I’ve read only the opening chapter so far (which is remarkable) but the book looks ambitious and informative. Know that Sacco is not an Indigenous author (he is Maltese-American), and scholar colleagues versed in this area have shared some eye-opening critical points with me; still, Paying the Land will surely be worth your time. Gender and Sexuality (Feminist, Queer, and Trans Perspectives)Drawing Power, edited by Diane Noomin, is a stunning anthology of stories about sexual violence, harassment, and survival. Strong, stinging, varied work there, sometimes harrrowing—a response to #MeToo. Maia Kobabe’s nonbinary memoir, Gender Queer, is tender and revelatory. You could call it a YA book, though of course its reception in YA circles has been fraught. (It's a frank depiction of, among other things, gender expression and sexual exploration — so, well, let's just say that some Amazon customers disapprove.) Look for the LGBTQIA anthology Love Is Love, a 2017 benefit to help victims of the Orlando nightclub shooting—short comics, but often powerful, and varied in approach. Justin Hall’s No Straight Lines: Four Decades of Queer Comics is essential history. Edie Fake's Gaylord Phoenix is a mind-altering, phantasmagorical quest fantasy from a trans perspective: a mostly wordless transition fable that rewrote the way I think about comics! Highly recommended. (Be aware: this is not tagged as a young reader's book, and includes startling images of violence and self-harm as well as sexual abandon.) Disability, Graphic Medicine, and CareCheck out the graphic medicine movement, devoted to comics treatment of illness, wellness, and dis/ability: see https://www.graphicmedicine.org. Note also the prevalence of disability memoirs in comics that are not medical in focus, e.g. Cece Bell’s great children’s comic, El Deafo; or the very recent (fictionalized) YA book, The Dark Matter of Mona Starr, by Laura Lee Gulledge, about depression; or any number of webcomics about life on the autism spectrum. Kabi Nagata’s manga My Lesbian Experience with Loneliness concerns not only sexuality but also anxiety and depression. Allie Brosh’s work also addresses depression and anxiety (Hyperbole and a Half; Solutions and Other Problems). Katie Greene’s Lighter Than My Shadow depicts her life with anorexia and an eating disorder. I highly recommend Vivian Chong and Georgia Webber's collaborative memoir, Dancing after TEN, which recounts a life-changing medical crisis for Chong that robbed her of sight; as well as Webber's own solo book about literally losing her voice, Dumb. Re: aging and elder care, see such graphic memoirs as Roz Chast’s Can't We Talk about Something More Pleasant? and Joyce Farmer’s Special Exits. Just a random recommendationFor depiction of progressive activism in a near-future dystopia, basically just a few steps from our own, read The Hard Tomorrow, by Eleanor Davis. This one rattled me, and it's beautiful. One last note (preaching to the choir?)As many KinderComics readers may know, children’s and young adult graphic novels are the fastest-growing, most robust sector of comics publishing in the US. They often deal with complex immigrant or minority experience, and offer queer-positive portrayals as well. Check out anything by Mariko Tamaki, Jillian Tamaki, Jen Wang, or Tillie Walden. This publishing movement is really doing bold new things in queer representation and identity narrative.

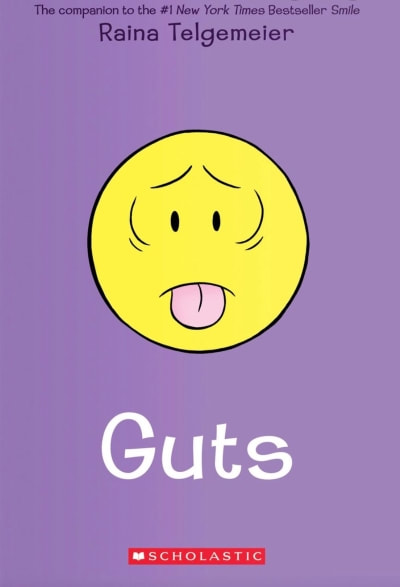

Guts. By Raina Telegemeier. Scholastic/Graphix. ISBN 978-0545852500 (softcover), $12.99. 224 pages. Raina Telgemeier is an engine, a star, a phenomenon. All of us who follow the world of graphic novels have heard this. For several years Telgemeier has borne a job description that, until recently, perhaps no one imagined we would ever need: America’s best-selling graphic novelist. Hype surrounds her like a halo (go, Raina!) Her success is proof of the graphic novel’s decisive new mainstreaming, and further proof, if any were needed, of the buying power and cultural clout of tweenage girls. She is, we’re told, “the Judy Blume of graphic novelists,” and her stardom has been a bellwether of the children’s graphic novel movement. Telgemeier’s publisher, Scholastic, has capitalized on all this with gusto, rolling out the red carpet for each new release and boosting Raina to million-copy print runs. Earlier this year, a spinoff product, Share Your Smile, a kind of “interactive journal,” signaled a new phase in the branding of Raina: an exhortation to her readers to write their own autobiographical stories in the vein of Telgemeier’s breakout books, Smile and Sisters. I honestly don’t know what to think of Share Your Smile, which seems more about design than revealing content: a guided activity book comparable to Wreck This Journal, The Diary of an Awesome Kid, and so many others. I suppose I had wanted to see something more reflective or essayistic, less about prompts and nearly-blank pages for readers to fill in. (It strikes me that young readers may get more from how-to cartooning books like James Sturm et al.’s Adventures in Cartooning or Ivan Brunetti’s Comics: Easy as ABC!) Telgemeier’s latest, though, Guts, now that’s a real book — and for me, her best. Guts is a middle-grade girlhood memoir akin to Smile and Sisters, and designed to match (Telgemeier’s autobiographical books and fictional books are distinguished by different design schemes). It’s in familiar Raina territory: a story of social awkwardness and anxiety, family and friendship, and the minute moral decisions and moments of confusion, defensiveness, and selfishness that can make school life so complicated. Predating the events of Smile, it depicts Raina, the author’s childhood self, going through fourth and fifth grade. Though it matches its sibling titles (indeed, Scholastic has just released all three in a boxed set), it stakes out its own thematic turf, revealing Raina’s anxieties and phobias in an emotionally charged way that goes a step further. It’s a brave book, and, I’m tempted to say, one that only a well-established children’s author could get away with. Guts depicts panic attacks and (as the title hints) upset stomach, cramping, and retching, as well as social and eating-related anxieties. It joins the considerable body of autobiographical comics that deal with anxiety, psychological distress, and neurodivergence. (Such themes are foundational to autographics as a genre, from Justin Green onward.) For a middle-grade graphic novel, Guts is, well, gutsy; it includes many scenes visualizing physical and psychological discomfort, and in some cases sharp pain and outright terror. It also includes quite a few scenes of bathrooming, bodily embarrassment, doctor’s office visits, and therapy sessions. “Treatment” is essential to its story. In short, Guts contributes to the graphic medicine movement. In the process, it yields the most harrowing and inventive pages Telgemeier has yet created. At the same time, Guts is very much a young reader’s book, never forgetting its main audience and taking care to explain and palliate the scary stuff—not with promises of quick cures and happy-ever-afters, but by showing that anxiety and panic are survivable and can be understood and, with practice, coped with and reduced. Young readers who dig Telgemeier’s books are likely to find Guts a warm, awkwardly funny, and ultimately reassuring guide. I tend to think that Telgemeier’s best books are her memoirs. Her fictional graphic novels to date, Drama and Ghosts, have been well-intentioned liberal fables with under-examined premises (Drama has been faulted for reproducing romantic stereotypes of the antebellum South, and Ghosts for naive cultural appropriation and whitewashing colonial history). Both have tried to do good things: Drama is a queer-positive, gender-defying romance, and Ghosts a story of family affected by illness and disability. But they aren’t tough-minded books, and Telgemeier doesn’t quite skirt the pitfalls built into their premises. In her memoirs, however, Telgemeier has crafted a believably human alter ego, just anxious and at times selfish enough to pose serious ethical dilemmas, and she has a way of disclosing certain hard things that don’t get solved, even as her boisterous cartooning conveys a bright, affirming outlook on life. The balance is exquisite, and Telgemeier usually nails it. Guts is the Raina book I’ve liked best. I will remember its formal gambits (startling for a middle-grade graphic novel) and its honesty. Telgemeier, at once a first-class storyteller and a commercial powerhouse, has clearly hit her stride. This book take chances, the chances pay off, and I’m impressed by the way she manages to walk the tightrope.

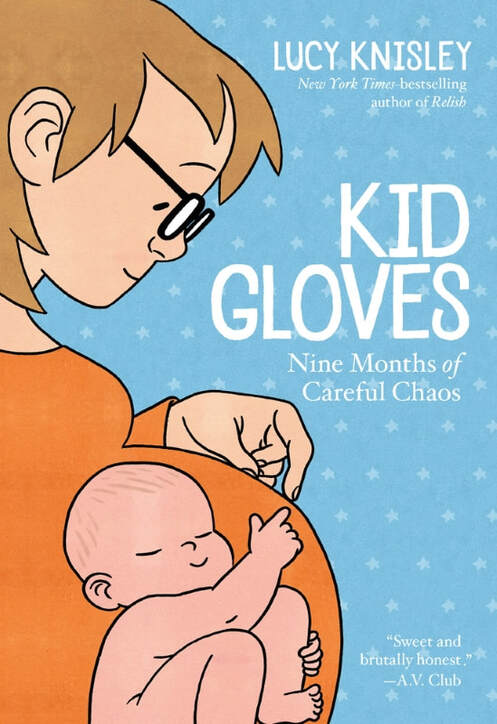

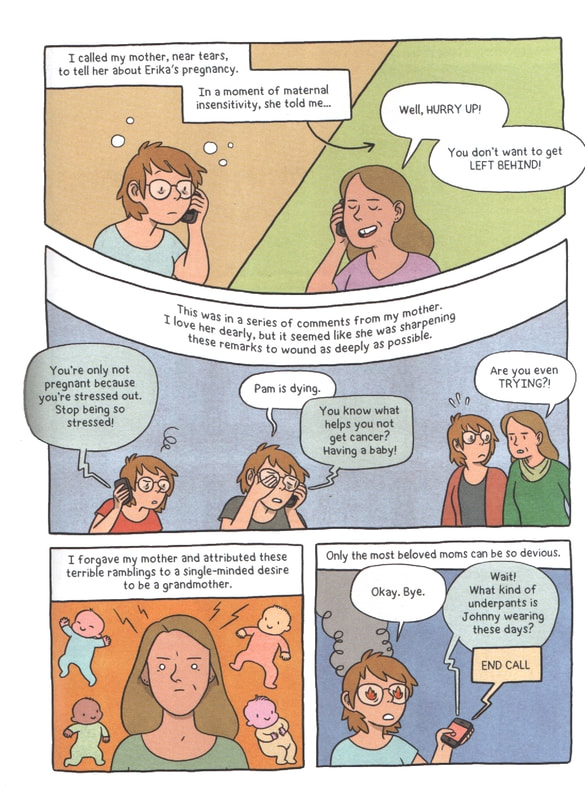

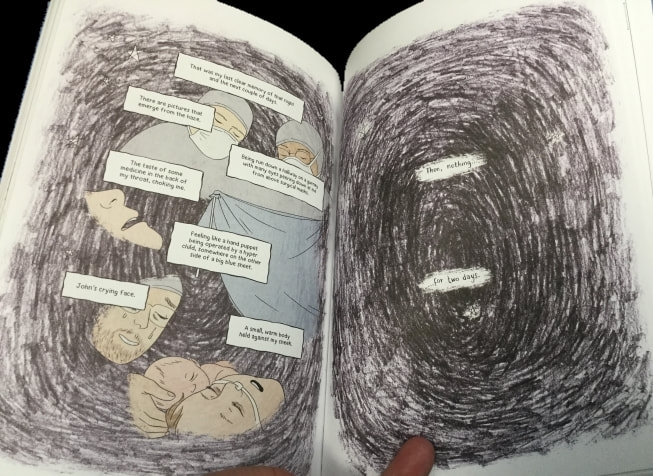

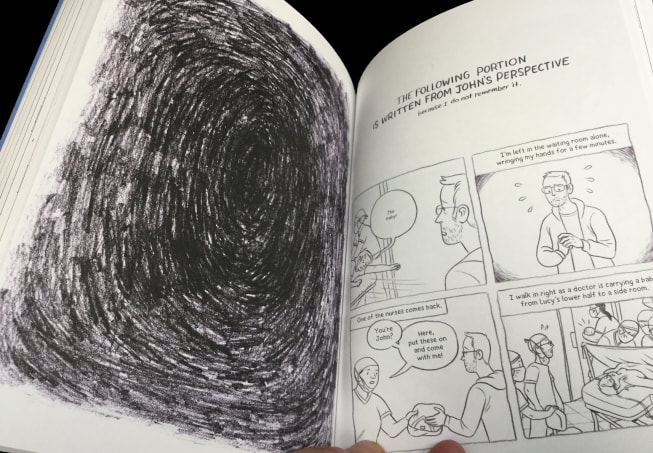

Kid Gloves: Nine Months of Careful Chaos. By Lucy Knisley. First Second. ISBN 978-1626728080 (softcover), $19.99. 256 pages. Kid Gloves tells of author Lucy Knisley’s pregnancies and miscarriages, and finally the birth of her and her husband’s child. Blending memoir, childbirth education, and self-help, the book also offers, at times, sharp criticism of both sexist birthing institutions and natural childbirth truisms. Between chapters of personal narrative, Knisley inserts brief interchapters devoted to “pregnancy research”—actually, a mix of contextualizing details and Knisley’s pointed editorializing: often humorous, sometimes exasperated. These interchapters are didactic but droll, and not impersonal; they resonate with Knisley’s own story. The larger personal narrative takes us through Knisley’s miscarriages and resulting depression, then on through the conception, bearing, and delivery of her child—itself a traumatic, life-threatening event (due to eclampsia and seizure). A lot of scary stuff is replayed in this story, but also a great deal of joy and good humor. Knisley comes across as a friendly but not uncritical guide to the vagaries of pregnancy, opinionated, blunt, and confidential. She relays her story from a safe retrospective distance: her introduction shows Lucy and the baby, weeks after delivery, doing okay, and the narrative captions reassuringly carry us along. That is, the story is recounted in hindsight, rather than rawly dramatized. All this is delivered (sorry!) via Knisley’s reliably excellent, toothsome cartooning, dynamic yet readable layouts, and beautiful colors—signs of her offhand mastery of the craft. Wow, can she make comics. I admit I approached Kid Gloves a tad nervously, unsure of whether Knisley’s writing would be equal to her subject. My first experience of her work, her memoir Relish (2013), had frustrated me with what I took to be its unexamined entitlement, skirting of emotional complexity, and preference for glib affirmation over fierce self-examination. Knisley does not do raw confessionalism or self-damning underground memoir. While her work does take on hard things, she tends to adopt a position of earned confidence and matter-of-factness (again, self-help is a useful point of reference). Her rhetorical construction of self is not the fractured self of Green or Kominsky-Crumb, nor the compulsively self-questioning, reflexive self of Spiegelman or Bechdel (though she does indulge here in comically grotesque caricatures of her changing body and its trials). Knisley the narrator seems secure even when Kid Gloves depicts the depths of depression or the harrowing trials of illness and emergency. It is a reassuring sort of memoir that offers a sane perspective-taking rather than an unsettled, open-ended questioning (in this, it reminds me of what Ellen Forney has done in her memoirs of bipolarity). Indeed, at times Kid Gloves skates over complex things much as Relish did. For example, in a sequence that my wife Michele called to my attention, Knisley recalls the aftereffects of one of her miscarriages, and what she characterizes as her mother’s insensitive response: You might think that this characterization would lead to a considered treatment of her mother throughout the remainder of the book, one that would balance daughterly love and forgiveness against frustration and critique. But Knisley accepts this tension between mother and daughter as an unresolvable, and moves on, not revisiting these hard feelings but tucking them away. (You won’t find here, for example, the extended, ambivalent treatment of parent-child relationships that you’ll see in Thi Bui’s The Best We Could Do.) I worried that this key moment, which comes early in the text, would cancel Knisley’s piercing depictions of depression, that she would paper over complexities in the quest for a feel-good equanimity such as we so often see in popular memoir and self-help books. Knisley, however, proved me wrong. Her narrative goes on to address challenging issues, including her and her husband’s anxieties, her triggers and preoccupations, the wrenching bodily demands of pregnancy, and her tense relationship with childbirthing dogma. The actual birth of her son, accomplished by cesarean and blurred out by medication, brings an explosive change to Knisley’s pages, suggesting lingering trauma and loss. Further, when her own life hangs in the balance, Knisley switches focalization to her husband, with drastic changes in her technique. There are moments when her always decorous, conspicuously well-designed pages become unsettled and the delivery of her story becomes most piercing. The book’s climax moved me beyond my expectations. Michele read Kid Gloves before I did, and told me frankly that the book raised up some difficult memories for her. This was perhaps another reason why I approached the book with a bit of dread. It’s true that reading it brought up some of my own memories of how Michele and I wrestled with medicalized childbirth and its outcomes. Frankly, I was surprised by how much Knisley criticizes natural childbirth rhetoric and embraces what she calls “hospital-based interventions” (even as she recounts what were arguably cases of medical malpractice). Kid Gloves, it's fair to say, takes a jaded view of the power struggles between obstetrics and traditional midwifery. These notes brought up memories of our own childbirthing experience; they also got me to question Knisley's wisdom. At times, the old feelings of impatience regarding her writing came back to me. There was a whiff of unexamined entitlement about Knisley's weighing of women’s “choices” in childbirth (“as long as everyone’s healthy”), and behind her settled self-presentation I sense a certain hardheadedness. But, still, Kid Gloves is a forthcoming and bracing story, one that will surely prove inspiring to many readers going through the childbirthing experience or seeking to put it into perspective afterward. By book’s end, I felt grateful for the ride. In sum, Kid Gloves uses the all-at-onceness and richness of the comics page to tell a story that is at once personal, instructive, and political. I don’t quite love it the way I love comics that tell of childbearing from a rawer, less protected place (check out Lauren Weinstein’s superb Mother’s Walk), and I note that Knisley continues to walk the knife’s edge between personal exploration and tidy, marketable endings. But Kid Gloves marks a step forward for her as a writer, and I recommend it.

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed