|

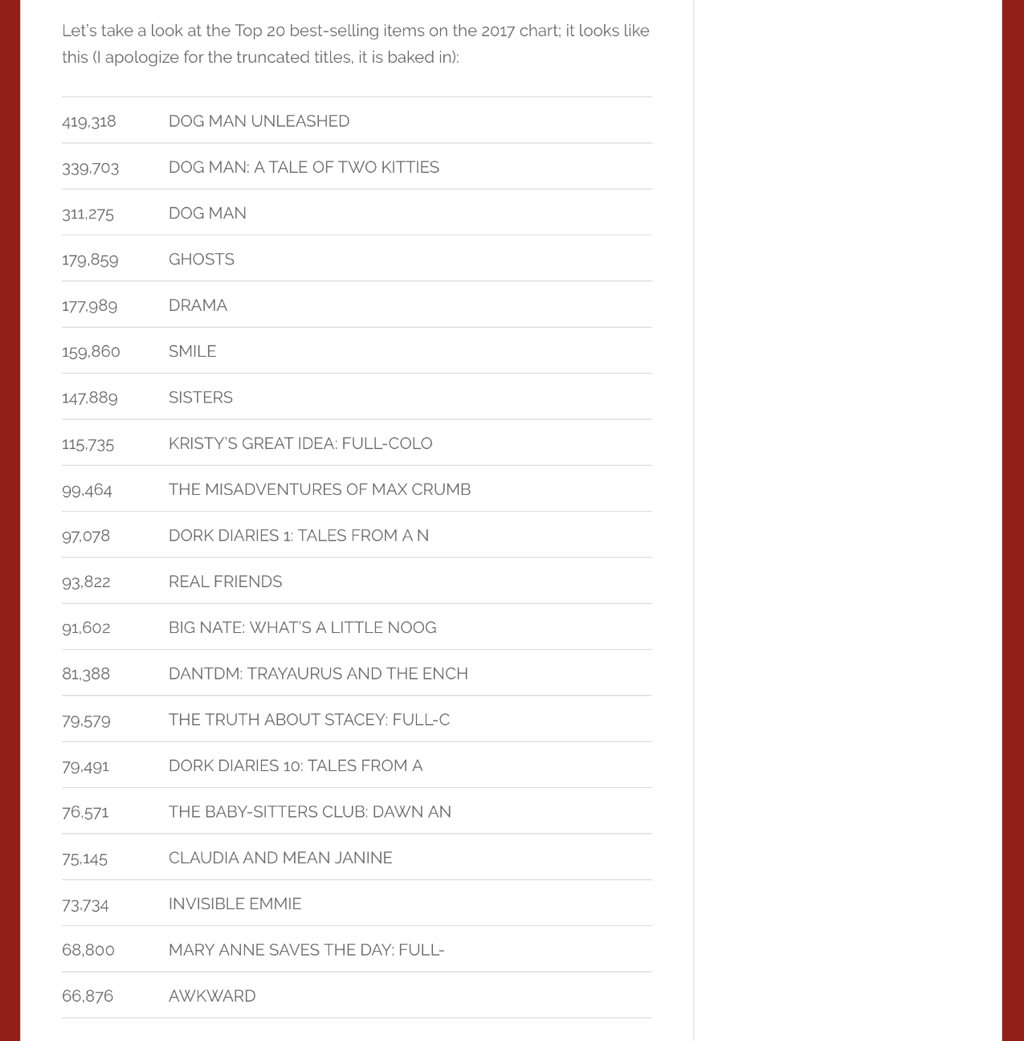

Over the past two weeks, two of my favorite comic shops, Modern Myths in Northampton, Massachusetts, and Meltdown right here in Los Angeles, have announced that they are closing. News like this is becoming increasingly common these days, dovetailing with general news about America’s so-called retail apocalypse. Certainly the news coming out of the direct market, i.e. the specialized comic shop market, in 2017 was quite discouraging (see analysis and opinion here, here, here, and here). I’ve been a loyal direct market customer, and something of a historian of the market, for years (my first book, Alternative Comics, posits a likeness between comic shops and 18th and 19th century lending libraries, and suggests that shops, besides selling, also help to educate their clientele). I’ve seen upticks and downturns, crests and troughs, in the market again and again, and watched a number of beloved shops come and go; there’s always a fierce rate of attrition among comic shops, since the direct market is a bastion of independently-owned small businesses that tend to run on narrow margins. As Dan Gearino notes in his recent book Comic Shop, the direct market suffered in 2015, but bounced back somewhat in 2016 — this sort of dynamic is familiar. But this time, I must admit, things feel particularly dire to me; I worry that there will be no easy bounce-back, that indeed the direct market may indeed be at a discouraging pivot point. Compounding this threatening downturn in the market, for me, is my own sense of alienation from what actually works in the direct market — a sense of weariness bordering on distaste. The best-selling comic in the direct market for the past few months (Doomsday Clock) is a project I dislike on its face, and, in my mind, confirmation of everything that is lame, inbred, and derivative about current superhero comics, which like it or not are the life’s blood of the DM. Further, there appears a serious disconnect between promisingly progressive books that sometimes move in the mainstream book trade and those comics that actually flourish in the direct market (cue here the ongoing discussion about the diversification, or not, of the DM). There is so much to cherish about comics today — in truth we are in a veritable Golden Age — but this does not seem to be borne out by most of what moves in the DM. As someone who loves comic shops and thinks that the historic and artistic importance of the direct market is still not fully appreciated, this saddens me. But: the direct market is no longer the be-all and end-all of comics, of course. Comics retailer Brian Hibbs has been tracking and analyzing BookScan sales numbers for the past fifteen years (!), and his most recent analysis, published just last week at The Beat, gives a deep if inevitably partial view of how graphic books are selling outside of the direct market. (BookScan tracks much of the mainstream book trade, per Hibbs: “Barnes & Noble, Amazon, Costco, General Independents, ...Hudson Group, ...Follett Books, ...Powells, ...Sam’s Club and Walmart,” among others, but not comic shops, libraries, schools, and book clubs.) Hibbs charts the Top 750 items as reported by BookScan, and looks at both 2017 and the “long tail,” or deep continuing trends, for specific titles, creators, and publishers. It’s a long, careful piece — Hibbs is careful to note the methodological problems inherent in his analyses, and acknowledges where his data is incomplete — but here’s a couple of the takeaways: HIBBS: Clearly, the first thing you can’t help but notice is that all twenty of the Top Twenty are books aimed at younger readers – it was just eighteen last year, and fifteen the year before. You have to hit #23 before you reach a book aimed at adults (“Persepolis”), #29 before you hit a book aimed at adults that could be considered DM-driven (“Saga” v7), and a staggering #36 before you reach something that that is a superhero comic (“Batman: The Killing Joke”). [...] HIBBS: “Kids” comics is absolutely the hottest demographic of the moment, reminding me in any ways of pre-Direct Market times when comics were on the newsstands and the audience was assumed to turn over every several years. One difference between then and now is that when those kids turn over, [Dav] Pilkey and [Raina] Telegemeier and all of the rest of these authors will still be waiting for the next incoming group of kids because these are permanent formats, not transitory ones like periodicals were.” It was precisely this sense of the growing importance of children’s comics that led me to launch KinderComics. Really, that’s why we’re here. Now, this is not to say that the young reader's graphic novel market is entirely healthy and represents a future of smooth sailing for children's and young adult comics. That's not the gist of Hibbs's analysis. Sales outside of the direct market in 2017 were not so stellar as to justify unqualified celebration; print publishing in general does not seem so robust. Further, the DM remains an important conduit for much of comics culture in the US and Canada, so I continue to be concerned about its under-performance, persistent neglect of young readers, and increasing irrelevance or self-marginalization. However, Hibbs's report makes clear that the general book trade is where it's at when it comes to book-length comics for younger readers, and there are very strong sellers there. One cautionary sign in Hibbs's analysis is just how much of the Top Twenty (even more than the Top Twenty) consists of works by a few favored authors, such as Pilkey, Telgemeier, and Rachel Renée Russell — a lopsidedness that, I worry, may not bode well for the future. Still, if further confirmation of the relevance and economic clout of children's comics were needed, I'd say that Hibbs's latest report gives that. This old direct market fan and collector is having to retrain his vision.

0 Comments

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed