|

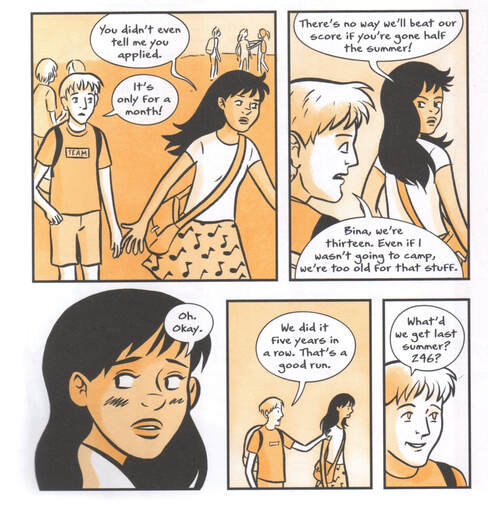

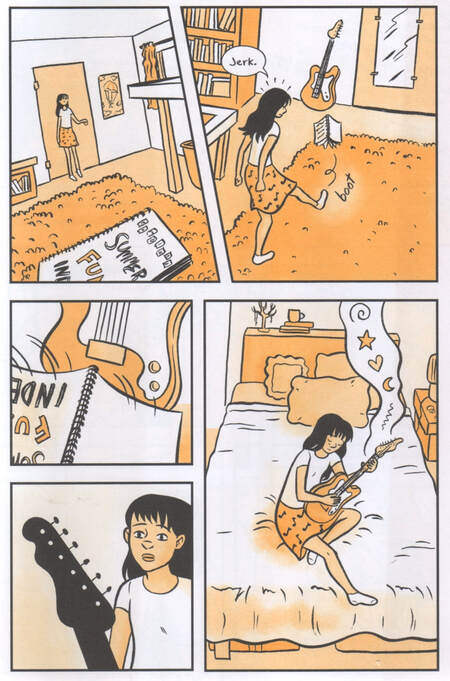

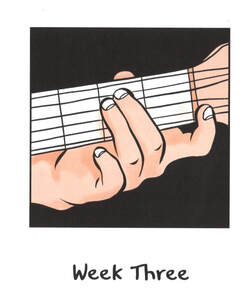

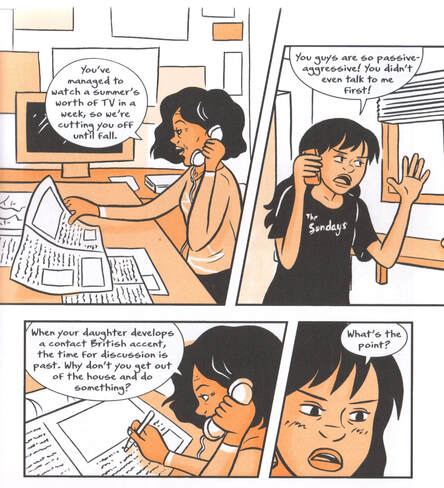

All Summer Long. By Hope Larson, colored by MJ Robinson. Farrar Straus Giroux, May 2018. Paper: ISBN 978-0374310714, $12.99. Hardcover: ISBN 978-0374304850, $21.99. 176 pages. All Summer Long is as interesting for what it doesn't do as for what it does. A teen-to-tween story of nervous friendship and awkward changes experienced over one summer, this middle-grade graphic novel hints at the familiar transition from palling around to the first tentative steps of romance—but it doesn't go there, and it's the better for it. Protagonist Bina, a thirteen-year-old girl, lives in suburban Eagle Rock, California, and has just completed seventh grade. As summer looms, she rather possessively longs for the usual months of uncomplicated fun with her best friend and neighbor Austin, but instead finds Austin changing, and her own social life unmoored. The novel recounts the ensuing summer, a bewildering stretch that, for Bina, climaxes in discoveries that kick up her musical aspirations and sense of self a notch. Romance plays a part in all this, but it's not the romance of Bina and Austin, nor indeed any kind of courtship story for Bina; instead it's about growing up a few small steps. Bina's story is not starkly gendered, nor does it follow a heteronormative romance plot. Rather, it's about one particular girl with a passion for music, anxious not to be left behind by her best friend but also learning that the two of them can be separate, different people. Modest in scope—the book spans just ten weeks or so—All Summer Long does not boast a complex, nail-bitingly suspenseful plot or pose terrible moral dilemmas. It's all about characterization and observation, in one short, focused, tightly-written arc. As such, it plays to author Hope Larson's strengths. The plot setup is simple. Austin's month-long sojourn at soccer camp upends his and Bina's fond summertime tradition of keeping a "combined summer fun index" (a playful numeric scoring system): Bina, feeling adrift, gets mad, sad, bored, and, finally, musical, playing her guitar and getting into a favorite new band: Bina tries to keep up contact with Austin via texting, but long silences from him, and then telltale signs of separateness or withdrawal, leave her feeling lost. She strikes up an odd friendship with Austin's much older sister, Charlie, but there the age differences prove too great for anything like an equal friendship. Austin returns from camp different than when he left, and needs space; Bina feels rejected. Even the shared experience of a gig by Bina's favorite new band doesn't help. The two friends fall out—but then Bina learns what's really been going on with Austin, a discovery that brings reconciliation while also definitely canceling any possibility that the two will pair up romantically as per the stereotypical adolescent courtship plot. The book ends by affirming Bina's budding sense of identity as a musician (an emphasis hinted at by the cover and the chapter breaks, which suggest her dedication to guitar practice). Mild spoiler: her friendship with Austin, though now less exclusive, endures. The events of the summer look different in the rear view mirror, so to speak, and Bina enters eighth grade with a newfound sense of who she is and what she wants. The denouement is both definite yet open-ended enough to invite the reader to think about what's coming next (online info suggests that All Summer Long is part of an "Eagle Rock Trilogy," though I saw no signs of this on the book itself). All Summer Long recalls Larson's early graphic novel about summer camp, friendship, and coming of age, Chiggers (2008). Aesthetically, its tangerine-soaked two-color scheme (courtesy of colorist MJ Robinson) gets closer to her adaptation of A Wrinkle in Time (2012), in which a light blue served as the second color. Larson has become increasingly fluent and emotionally nuanced as a cartoonist (Wrinkle, a demanding project, seems to have tested and extended her skills). All Summer Long is not a subtle or elusive text; the important thing is that the art communicates, words and pictures working in tandem, keyed to physical action but especially to the rhythms of dialogue. In fact, dialogue is one of Larson's not-so-secret weapons. Her characters have a sense of humor, and know how to spar verbally. Dialogue exchanges are brisk, and Larson has a playful way with language:  I confess, though, that I don't find Larson's drawings very transporting. They are good at conveying the in and out of relationships and the lived-in business of feeling and negotiating. They're likewise good at putting characters in spare but habitable spaces, and working out their interaction visually and physically. Only occasionally do they give off any mystery or magic. This was a problem for some of my students, and for me, when I recently taught Larson's Wrinkle alongside Madeline L'Engle's original novel. Larson's adaptation does many things well: it is patient, thorough, as close to the details of L'Engle's text as it can get, and yet eminently readable. Larson (and her publisher) made a good decision in letting the story breathe and expand (up to near 400 pages), a call that too few makers of comics adaptations of literature are willing to make. Larson's Wrinkle cleaves to L'Engle, parses out the action carefully, and seeks to uphold the original's weirdness (despite Larson's confessed aversion to L'Engle's religious themes). She does all she can to give the novel a measured, thorough, and deep treatment. But when it comes to depicting the spiritual, the metaphysical and cosmic, the book falls oddly flat, with prosaic images that, perhaps inevitably, cannot capture L'Engle's use of paradox and self-cancelling figures of speech. My students were quick to pick up on L'Engle's impossible descriptions, which at once invite but frustrate any literal visual depiction. They were also quick to criticize Larson's pages for not living up to those mystical, or I might even say theological, moments. Those passages appear to call for an escape from the grid, from careful, measured steps, and a plunge into the odd and disorienting. Larson doesn't really deliver that, though. She does use layout ingeniously to convey the impossible experience of tessering (transporting), but her alien vistas and creatures tend to be rather ordinary. It's clear from Larson's work as a comics writer (for example, the seafaring adventure of Four Points, with artist Rebecca Mock), or indeed from the magical elements of her early graphic novels (e.g., Gray Horses; Mercury), that she has a yen for the fantastical, but her own drawing seems more methodical than dazzling. All Summer Long, again, plays to her strengths. Larson has been a prolific creator, from her early burst of original graphic novels (2005-2010), through the long haul of Wrinkle, to a lot of subsequent work writing for other artists: again, Four Points, but also Who is AC?, Goldie Vance, and Batgirl. (She has also written and directed a short film.) All Summer Long is her first solo, self-drawn book since Wrinkle, and comes after a brief period during which, it appears, she struggled to sell a new graphic novel, but then moved into a long spell of collaborative work, much of it in periodical form. After all that, All Summer Long seems to tack in the direction of current tastes; it's the kind of book that is all the rage in graphic novels today: namely, a middle-grade coming-of-age story about and for girls. This is not startlingly new territory. But Larson is good, very good, and if All Summer Long leads to a series of books in a similar vein, they will be worth the reading.

0 Comments

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed