|

Punk Rock Karaoke. By Bianca Xunise. Viking, ISBN 978-0593464502, April 2024. US$24.99. 256 pages, hardcover. Punk Rock Karaoke, a YA graphic novel, is a high-spirited valentine to punk and Black queer music-making. It's also a love letter to Chicago (the author's home base) and community. The plot follows three recent high school grads, Ariel, Michele, and Gael, and their hopes for their struggling punk band, Baby Hares. Mostly it's about Ari and her crisis of faith, as she falls out with Michele, her best friend, and seeks comfort and encouragement in the arms of another musician, a local punk legend. At first this guy seems to care for her, but in the home stretch we learn otherwise. The story turns into a parable about cultural appropriation and exploitation, as well as a tribute to the sustaining power of friendships. Graphically, the book is a gas. Bianca Xunise values expressiveness at least as much as conventional narrative clarity, and draws vivaciously, explosively even. This is distinctive work. Drawing for the extended graphic novel format seems to free Xunise up and take them beyond their well-known work in Six Chix and various online outlets (I first saw their work at The Nib). Xunise tucks in many visual asides, or telling details, about Chicagoland, and man, can they convey the energy of friends making music together: So, there are many visual delights in the book. Story-wise, alas, I'm not convinced. Punk Rock Karaoke rigs its plot to make a Point, and to me that point was obvious and predictable about a quarter of the way in. Spoiler alerts are needless, as you can see the twists coming. Though the energy of gigging and moshing is undeniable (and infectious), the novel's depiction of life in a band feels unreal. Despite a stated focus on community, Punk Rock Karaoke becomes a standard rock 'n' roll story about "making it," and it feels like wish-fulfillment rather than a hard-hitting YA novel. Its politics are vague. Beyond a neighborhood fair (where the Baby Hares play a crucial gig), the plot stays narrowly focused, favoring Ari's perspective. Inevitably, her fling with an exploitative outsider brings disappointment and bitter wisdom. In this case, wising up means sticking with your buds and resisting cooption — but this message feels defensive and narrow, and the book contradicts itself. Xunise champions, rather than examines, the usual punk attitudes about being authentic and not a "poseur," and yet the conclusion demands that the Baby Hares get noticed by an industry mogul who thinks they have potential (a trope familiar from countless backstage musicals). The story finally falls into a heavy-handed allegory about appropriation in which the characters serve as mouthpieces. I found all this simplistic, and longed for less rigging, more questioning. Punk Rock Karaoke has lively cartooning on its side, but to me its lessons feel predetermined rather than earned.

0 Comments

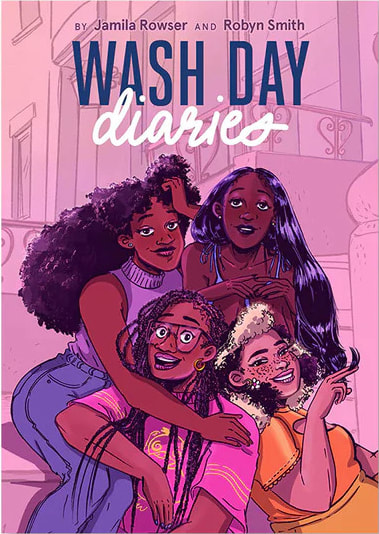

This post is the third in a series of three. On Friday I reviewed this year’s Eisner Award nominees for Kids (roughly, middle-grade readers). Today I turn to the nominees for Teens, that is, Young Adult books (see my post of May 17 for an overview of all young readers’ categories). Once more, I’ve tried to describe every book fairly, while signaling my favorites. The Teens category is amazing this year! Of course, this is all about getting ready to cast my votes before the June 6 deadline! (For info on voting, see here). Blackward, by Lawrence Lindell (Drawn & Quarterly). Four friends run a club for queer, nonbinary, and otherwise “alternative” Black folx. With the help of a bookstore owner, they organize a Black zine fest to build community, while fending off online hate from reactionary, homophobic voices. Blackward is a hilarious, high-spirited mash note to zinesters, organizers, and the kind of friendship that creates new cultural spaces. It’s also a knowing satire of Black community frictions. Lindell’s cartooning is quirky and wild, and sometimes strains to its limits. Yet he uses repetition and braiding to great effect, and the characters are great. I bet this book will change lives. Danger and Other Unknown Risks, by Ryan North and Erica Henderson (Penguin Workshop). Like Mexikid, this made my TCJ Best-of list. Since then, I’ve read many books I wish I had read earlier, so if I were writing that list now, it would look different. This book, though, would still be on it. A brilliantly engineered fantasy about a transformed, postapocalyptic world, Danger offers an adventure in thinking. It rewires a conservative premise (saving the old world) into something wiser (welcoming in the new); ultimately, it’s about embracing change rather than clinging to an idealized past. Ingenious, dizzying, moving, and gobsmackingly drawn by Henderson, this one has captured my heart, and my vote. Frontera, by Julio Anta and Jacoby Salcedo (HarperAlley) In this blend of realism and magic, a young man, Mateo, slips across the Mexico-US border and crosses the Sonoran Desert, aided by the ghost of another man who died during that crossing almost seventy years earlier. The Border Patrol, vigilantes, and dehydration stand between Mateo and his goal, and he nearly dies, though he gets, and gives, help along the way. Frontera’s magical-realist plot works to refute nativism, as Mateo’s quest conveys complex truths about the geography and politics of the border. The climax, however, is generically heroic and feels forced. Graphically sharp, with stylized naturalism and expressive colors. Lights, by Brenna Thummler (Oni Press) The third and final volume in the Sheets series (unknown to me until now). A benign ghost is haunted by his inability to remember his own past, and why he died; his two living friends, eighth-grade ghost-hunters, help him recover those memories, while renegotiating their own complicated friendship. Delicately drawn and colored, Lights is also brilliantly written, filled with subtly observed moments of social negotiation and moral decision-making. Thummler is wise to the ways we typecast other people, limiting who they can be, yet the ending poignantly turns stereotype on its head. Stunningly good (and another one I’d vote for). Monstrous: A Transracial Adoption Story, by Sarah Myer (First Second) In this memoir of intercountry adoption, Sarah, a Korean child of a white family living in rural Maryland, struggles against racism, social ostracism, and bullying – and her fear of her own explosive anger. Frankly, given the unrelenting cruelty shown here, I often felt that her violent outbursts, or moments of fierce self-defense, were justified. Graphically, Monstrous is bold, imaginative, and sometimes frightful; drawing, for Myer, is clearly a high-stakes act of self-invention. Yet the story is anchored by retrospective text that seeks to narrate her experience calmly, from a stance of mature judgment, which softens its impact. Still, powerful work. My Girlfriend’s Child, Vol. 1, by Mamoru Aoi, translation by Hana Allen (Seven Seas) In the first volume of this ongoing manga, a high schooler’s unplanned pregnancy upends her life, tipping her into indecision and emotional turmoil that she cannot share with anyone else, even her sympathetic boyfriend. Aoi’s visuals are sensitive and devastatingly acute. Pensive, almost dreamlike, and marked by long wordless passages, the storytelling balances a sweet, idealized style against unyielding facts. Conversations are muted yet quietly agitated; visual metaphors are understated but fraught. The evocation of anxiety, tenderness, and naivete is overwhelming, and the sense of isolation often harrowing. No preaching here, just minutely observed and heartbreaking drama. I’ll be back. Some final thoughts: I like to treat comics of all varieties, and from all spaces, as cousins, and the comics world as a continuity. I maintain an interest in comics of just about every kind, and I try to follow comics publishing in several sectors. Yet I must admit, it is now impossible for me to “keep up” with comics in the US in any comprehensive way. The Eisner Awards of today, despite their roots in comic book fandom, represent an attempt to spotlight many different kinds of comics, and I appreciate that. Every year I see signs of progress toward greater inclusivity, as well as signs of strain. As a former judge, I can attest that focusing on and weighing so many different kinds of comics is a huge challenge. The Eisners are not guild awards; the US comics field is not a united (much less unionized) industry, and, as my colleague Benjamin Woo has pointed out, there really isn’t any such thing as a single “comics industry.” Nor is there a single comics community – the Eisners represent, and speak to, several different communities. The job of the judges, each year, is to craft a ballot that acknowledges that complexity and seeks out excellence of many different kinds. Honestly, I never read so many comics, in such a brief span, as I did when I served as a judge back in 2013. It was joyous work, but hard. This year’s Eisner ballot includes nominees in thirty-two different categories. I feel qualified to judge in maybe slightly less than half of those categories (what, maybe fourteen? Fifteen?). When I get around to casting my vote (by or before this Thursday, June 6), I will, as usual, struggle to figure out which categories I can fairly cast votes in and which I cannot. I will, as usual, feel as if I’ve missed important things. But I know that thinking about the Eisner nominees always gives me a better sense of what’s happening in the field (fields?). And I know that I greatly enjoy this custom of picking out at least a few categories and trying to get up to speed. My favorites in the Teens category are Lights and Danger and Other Unknown Risks, but I’ve enjoyed the whole process. Congratulations, nominees, and thank you, judges!

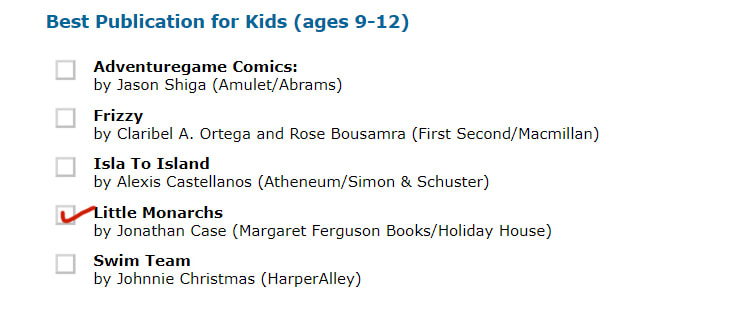

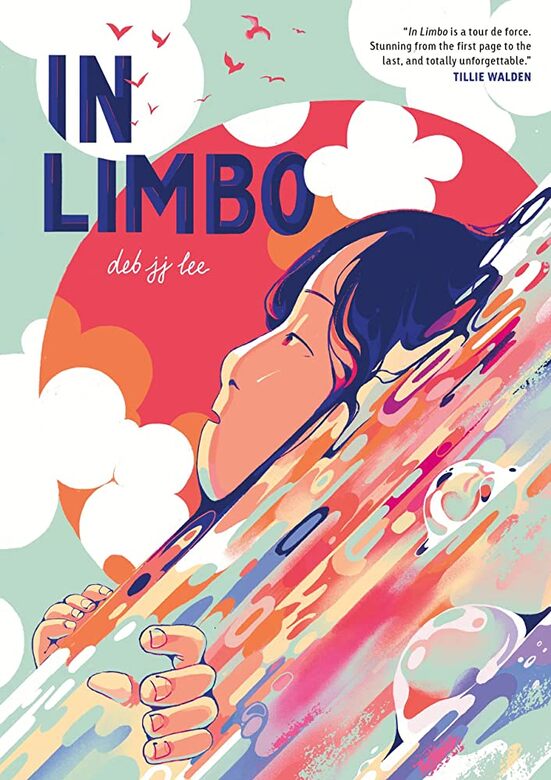

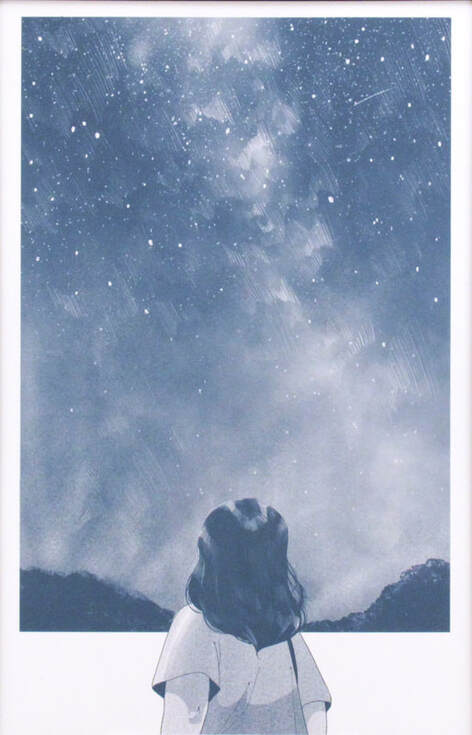

In Limbo. By Deb JJ Lee. First Second, ISBN 978-1250252661, 2023. US$17.99. 352 pages, softcover. I lost sleep over In Limbo. Foolishly, I started to read it late one night, when I was in a sticky, sort of unhappy mood that had nothing to do with the book and much to do with work. I needed to read something that was utterly different than the work I was obsessing over; I needed a way out of my spiraling. So, I thought I would start In Limbo before bed. Just start it, you know? Get my feet wet. But no — once I started, I had to finish. Damn. There was something quietly harrowing about the book, something that frustrated and gnawed at me. I think maybe I was angry with the book's protagonist, and her mother? Or maybe bothered by the evocations of racism, bullying, or depression? Struck by the contrast between the book's elegant, quiet style and its dark undertow? Whatever it was that got to me, I felt pretty helpless about it. I mean, I did put the book down for a few minutes, about a third of the way in, but then I grabbed it up again, anxiously, and plowed on. As the story got deeper and darker, I was all in. When I finished, it was well after midnight — and of course I had the story on my mind as I tried to get some shuteye. Again, damn. In Limbo is a graceful and refined graphic book, a beautiful feat of design, and a moody, enveloping story. It's also observant and brave. Thematically, the book treads some familiar ground: a high school memoir; a Korean immigrant's story; an exploration of familial tensions, crushed friendships, cultural in-betweenness, mental and emotional fragility, suicidal thoughts. The protagonist is a version of author Deb JJ Lee, and the story tracks her four years of high school, leading up to graduation and college after a long spell of desperation and loneliness. Okay, none of that feels unprecedented. But In Limbo is bothersome and riveting, a tough, involving work. I couldn't read it complacently. It pulled me in with its long silences, layered, emotionally telling details, fraught conversations, and occasional shocks. Its cloudy, blue-grey palette, monochrome yet somehow endlessly varied, feels soft, yet Lee uses it to create sharp, crisply defined pages — despite their refusal of black frame lines and their frequent use of bleeds. (Note that in life the author goes by they, but the book genders Deb as she, which, Lee says, more accurately reflects who they thought they were in high school.) Their layouts are often dense and maximally detailed, yet the overall impression is dreamlike, entranced. At first blush, it looks like a book that should be calm. But calm is not what the book is about, and reading it often hurts. What I'm trying to say is, this is a great and hard book. Briefly, In Limbo follows Deborah (Jung-Jin), or Deb, through her four years of high school as she tries to love and understand herself, embrace art as her vocation, and get out from under her family's expectations, especially the relentless needling of her very driven, at times abusive, mother. Her mom, as a character, hews perilously close to the "tiger mom" stereotype (as the book itself acknowledges). Their relationship is full of jagged edges and cruel scenes — and it's one of the things, I think, that caused me to read on, after midnight, in hopes of relief or understanding. Deb's father and brother don't register as strongly; In Limbo is very much a daughter/mother story. Yet it's also about friendships, sometimes fraught, overburdened ones. Deb's feelings for her friend Quinn, to whom she has a sort of desperate, proprietary attachment, lead to surprising reversals. Officially, In Limbo is described as "a cross section of the Korean-American diaspora and mental health," and that seems right, but it is Lee's depiction of complicated, ambivalent relationships that yields the greatest shocks. Lee doesn't show young Deborah as a good friend; instead, they show her taking friends for granted, or reading them strictly through the lens of her own anxiety, or laying terrible responsibilities on them. In this sense, the book seems self-accusatory. Deb doesn't understand what she's doing, of course, and the story is partly about her coming to grips with how she hurts both her friends and herself. Some relationships outlive the end of the book, others don't, but the book is remarkably generous in the home stretch, as Deb opens out from the tortured inwardness of the first half and learns to see more clearly. To say that the book's characterizations are complex would be a measly understatement. In Limbo doesn't resolve every problem it raises. This is probably partly by design; Lee has acknowledged in interviews (again, see this one) that their life, past and present, is more complex than a single book can cover, and the book seems anxious to show Deborah as a work always in progress. There are things in the book I'd have liked to know more about. Some relationships and threads are still nagging me, even now. Some readers may finish the book wanting to know more about Lee's understanding of internalized racism and the pressure to assimilate. Some may wonder about the connection between those things and the book's tormented mother/daughter dyad (cf. Robin Ha's graphic memoir Almost American Girl). Some readers may be anxious to know more about the mother's abuse, what prompts it, and how Deb lives with it (cf. Lee's own short comic from 2019, "Dear CPS," readable on their website). Some may wish that the Künstlerroman aspect of the book came through more strongly, that they were left knowing more about Deb's artistic vocation. Some may wonder about Deb's implicit queerness or perhaps about gender nonconformity. I've been thinking about all those questions; the book feels a bit tentative about what to include, what to leave out, and how to balance things. That said, I don't expect complete "closure" in memoir, and when I do get it, I worry that I'm being sold a bill of goods. In Limbo has honesty and emotional rawness despite its delicately finished surface, and I dig that. That "surface" is going to draw in and mesmerize a lot of readers, I expect. The book's rapturous reception has a lot to do with Lee's virtuosity as an illustrator and designer (indeed, the many blurbs on the cover note their lush, meticulous art). In Limbo is visually extraordinary; the book is gorgeous and transporting, a master class in narrative drawing and sustained mood. That mood is melancholy almost the whole way through, but In Limbo is vital and ravishing enough to make one fall in love with melancholy. (My images here don't do the book justice.) I'm grateful to this book for introducing me to a singular and gutsy artist. Most highly recommended: another high watermark for autobiographical comics about adolescence. <3

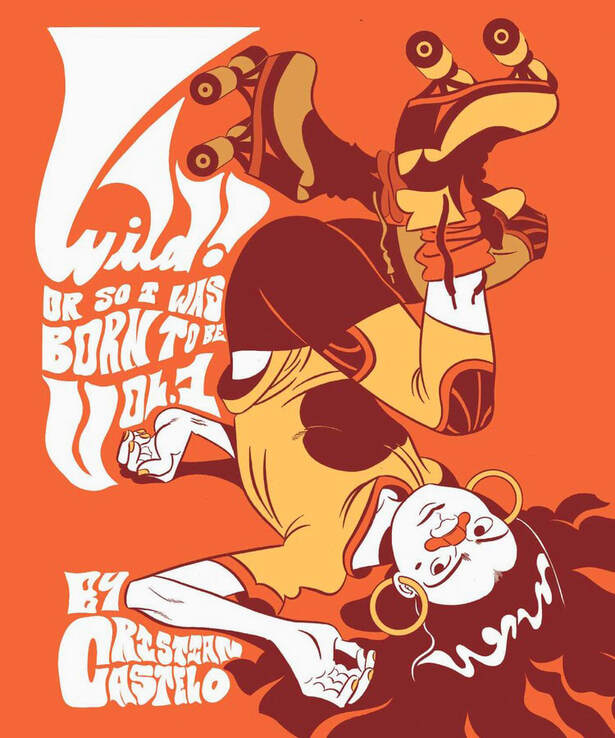

Wild! Or So I Was Born to Be, Vol. 1. By Cristian Castelo. Oni Press, ISBN 978-1637150931, 2022. US$29.99. 208 pages, oversized softcover. Wild is a delightful yet frustrating comic. Delightful because artist Cristian Castelo cartoons the hell out of it, with an energetic, superflat, ultrabright style. The pages sing. The story's 1970s roller derby milieu and fearsome all-girl cast (reminding me a bit of Jaime Hernandez's wonderful luchadores) grant him license to do colorful, braggadocious roller rink action and cartoon violence. It's a gas, full of fierce posing, trash talk, and big, mythic characters. The sizzling red/orange/gold palette, outsized format, and inventive layouts practically gave me a contact high! So, yeah, I enjoy rereading and poring over this comic. OTOH, Wild is confusing as hell. Beyond protagonist Wild Rodriguez and a couple of hard-bitten, superheroic roller divas, the cast is indistinct. Supporting characters blur into each other, and everybody lurches off-model. In fact, some characters don't seem to have a consistent model (in one scene, a very minor bit player ends up looking like four different people). The settings lack a 3D sense of habitable space, and action does not flow logically from panel to panel. Locales are gestural at best, and the high-throttle action scenes don't actually communicate anything about roller derby as a game. There is snarling and there is hitting, but what else is the sport about? The plot lunges here, then there; eccentric narrative doglegs turn out to be crucial (the accumulated effects of serialization are all too easy to see). Cross-cutting between different locales and different bouts makes the book's home stretch dizzying, and not in a good way. Castelo's elastic cartooning works somewhat against narrative coherence. His style has shifted a lot since this project began. In 2019, I bought one of the riso-printed, handbound collections of the unfinished Wild (then a work in progress) at comicartsla.com, and I can see remnants of that draft here, in panels that are not quite as crisp as the rest of the book. The newer style is razor-sharp and fairly staggering. At times, Castelo seems to have worked over (and around) the older stuff, punching it up, adding new connections, rethinking and complicating the story — but the end results don't add up narratively. Problems in simple legibility are made the worse by Castelo's expressionistic, ever-shifting use of his limited color palette; the characters' costumes are not taggable by color, because a yellow outfit in one panel becomes a red outfit in another. That may sound like a petty complaint, but it becomes a problem due to the sheer density of the pages, indistinctness of minor characters, and ill-advised cross-cutting between scenes. The book is just plain hard to follow. But man, what cool things are hiding in here: Wild Rodriguez's mixed family and ambivalent ethnic identity; the roller divas' complicated, nuanced backstories; the way the major characters bear the weight of cultural politics; the sheer unabashed ass-kicking comic fury of the story. One aspect that makes the reading even harder — the difficulty of parsing "dream" from "reality" — strongly appealed to me. So did the overwhelming style. I'm glad to see such a vaulting, ambitious, and, yes, wild comic touted as a YA book. Castelo may yet deliver a great all-around comic. I bet he will. In any case, I'll happily queue up for the next volume of Wild. My complaints notwithstanding, Volume One is a gorgeous, headstrong, gutsy experiment. I think it fails narratively, but it fails in such a way that I long to see what Castelo does next.

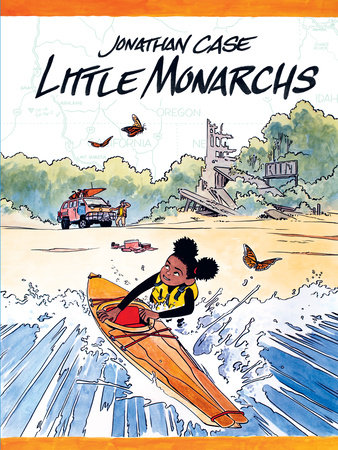

I like to keep up with the Eisner Awards. I'm a former judge, I value recognitions of excellence in the comics world (even when they're contentious), and I like staying in touch with the process. Honestly, it can be hard to find and read every single nominee, but each year I pay particular attention to, and try to spend time with, all the nominees in the young readers' categories. Currently, that means three categories: Early Readers, Kids (ages 9-12), and Teens. Over the past week, I've read about ten books to get up to speed! I'm told that today, June 9, is the last day to cast votes (officially, the vote is "open until June 10, 2023 12:01 AM (GMT-05:00) Eastern Time"). So, this evening I'm going to vote in as many categories as I feel qualified to vote in! This year's Eisner process has been especially vexed and controversial (leading to a retroactive withdrawal from the ballot). The ballot has been a bit mystifying to me, with some, IMO, startling omissions and puzzling categorizations. But controversy is in the nature of the awards, and I still appreciate the heuristic value of this, let's say, yearly exercise. Here are my thoughts on the Early Reader, Kids, and Teens categories:  Early Readers: I admit, this is not a category that interests me much this year. There are some lovely images here (for sheer sumptuousness, Dav's Disneyesque watercolors are hard to beat), and some nice comic bits (the page-turns of Higgins, the pacing of Willems), but for the most part these books strike me as pat and aesthetically undaring. There's a lot of shtick here, which tires me out. I miss seeing some good TOON Books in this category; 2022 seems to have been fallow for them. That said, my choice here is this charming, quietly ironic, aesthetically delicate take on friendship and learning:  Kids (9-12): This is a more interesting category by far, in fact one of the deepest in this year's ballot. The craft on display is impressive (dig the cartooning in Frizzy and Swim Team), and the ambition (dig the near-wordless storytelling of Isla to Island, a complex tale of immigration, loss, and discovery; or the interactive, formally ingenious Adventuregame). But my hands-down choice is Little Monarchs, an extraordinary piece of worldmaking, which is cartooned with an Alex Toth-like economy that reminds me of elegant classicists like Jaime Hernandez, R. Kikuo Johnson, and Chris Samnee. An amazing book, so dense, involving, subtle, and beautiful: Teens: It's nice to see Tillie Walden in this category, for a book that is a change of pace for her. But I think the outstanding title here is the already much-talked about, groundbreaking Wash Day Diaries, a suite of stories about four Black women and the strength of their friendship and interconnection. Every character in this book has a backstory, but Rowser and Smith smartly leave us guessing, focusing on the energy, grace, and good humor of the four. Darkness marks the edges of the story, but joy wins out. The book seems casual, the way eavesdropping on good friends can, but that's deceptive; there's a lot going on. The chapter devoted to their "group chat" is a wonder of form as well as characterization. I admit that I didn't see this as a YA book at first, but then, I usually have that reaction to books that turn out to be very good YA books! A few observations:

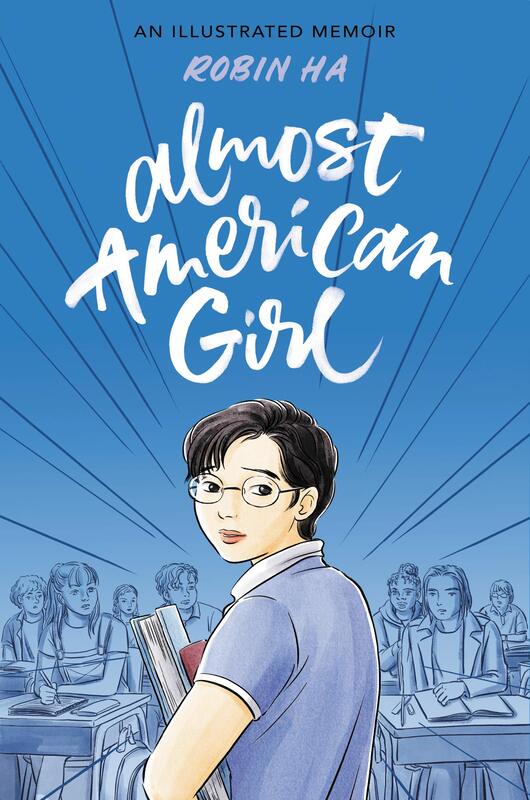

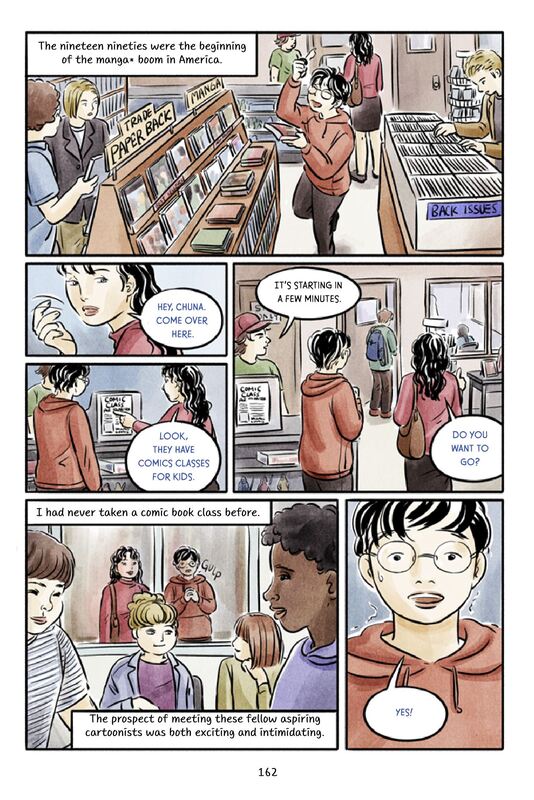

Almost American Girl. By Robin Ha. Balzer + Bray / HarperAlley. Paperback: ISBN 978-0062685094, US$12.99. Also in hardcover, Kindle, comiXology, and Nook. 240 pages. Robin Ha’s Almost American Girl, a Korean American memoir of emigration and acculturation, evokes hard truths and traumatic memories through a mostly gentle, almost decorous style. The style belies Ha’s toughness. A complex story of cultural displacement and loss, but then again gradual near-assimilation—or, better, ongoing negotiation of identity—Almost American Girl boasts a delicate watercolor aesthetic and, by contrast, stilted digital lettering. The style is sometimes straitened or stiff, yet tender and personal; the balance suggests both tentativeness and poise. I confess, I didn’t warm to it easily—but Ha’s story has stayed with me, provocatively. Young Robin, raised in Seoul, suddenly finds herself uprooted and forced to adapt to life in the US. Her mother, a single parent, makes that choice, indeed all the choices, for them. Ha’s complex relationship to her mother—who at first, it seems, did not want this book to get made—accounts for Almost American Girl’s pointed, unsentimental, and clear-eyed qualities. The book relives Ha’s memories of anger toward her mother, which could not have been easy to set down on the page, but also portrays her mom as a self-driven woman determined to break out of a South Korean society premised on gender conformity and suffocating moralism. Gradually, Robin develops empathy for her mother’s struggles, even as she learns to be critical of stereotypic gendering in her own life—and it is her (re)discovery of comics as an artistic outlet, a move encouraged by her mom, that enables Robin to stake out these positions. So, to say that Ha’s treatment of her mother is necessarily double-edged would be an understatement. The negotiations behind the book’s making must have been complicated. Just so, the finished book is hard and sort of unfinished. Much of it replays old hurts with fresh anger. In the home stretch, though, Ha fast-forwards into life changes that bring a warmer, more resolved ending; the book seems to leapfrog to its finish. This shift perhaps comes a bit too fast, reflecting, I suppose, the YA genre’s demand for at least some provisional resolution. However, to Ha’s credit, hanging questions remain. The result is clear but not pat, and emotionally rich. Almost American Girl joins other graphic memoirs of divided identity and enculturation in the US: comics about immigrants and immigrants’ children working their way into a robust but ambivalent sense of Americanness (Thi Bui, say, or Malaka Gharib). In this post-Raina moment of comics memoirs for young readers, the graphic story of renegotiated identity has become a distinct and powerful vein of storytelling. Ha adds worthily to that growing list, with work that is at once aesthetically subdued yet piercingly written. It’s very good, and I imagine it will make a big difference for many readers. PS. Dig Ha and Raina Telgemeier’s online panel from the recent Comic-Con at Home: a warm, collegial chat (with some drawing!). This has been one of my favorites of the many online “convention” events I’ve watched recently; you can tell that these authors are used to fielding questions from readers young and old. It is hard for me to imagine a Comic-Con panel like this fifteen years ago. Thank goodness the world keeps changing! Here's the video: Also, Robin Ha has a nice how-to / process video on YouTube, from this past May, courtesy of Epic Reads: see here.

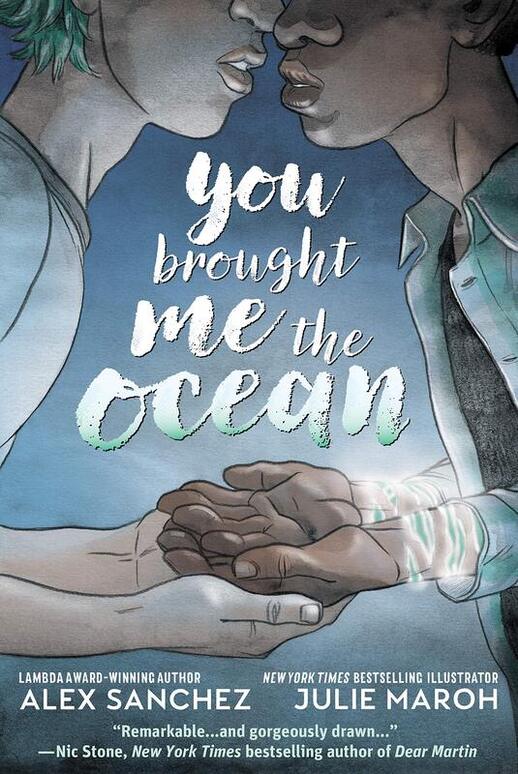

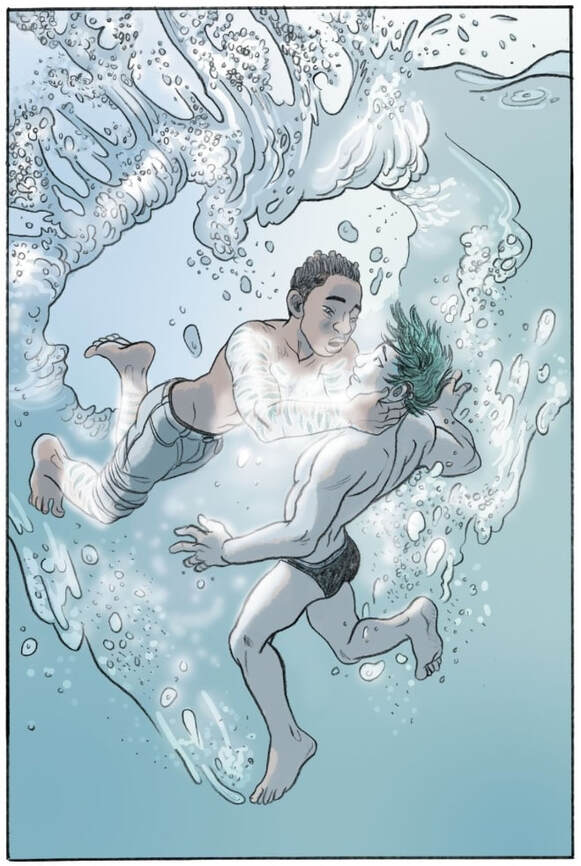

I have not been a fan of 21st-century DC Comics. Often I have criticized DC for not acting like a real publisher and for pushing more of the same ugly, self-defeating work: grim heroes, continuity porn, line-wide reboots, and other rigged and desperate moves. But nonetheless I found myself reeling from this week’s news of massive layoffs and restructuring at DC, part of a general purge at WarnerMedia (Heidi MacDonald has the best think piece on this that I’ve seen, over at The Beat). That was hard news. With DC losing a reported one-fifth of its editorial staff—indeed, as MacDonald says, “almost an entire level of editorial executives“—and the company’s publishing plans downsized, this seems like a fraught moment for comic-book culture here in the USA. I have to imagine that it’s a heartbreaking moment for many; the human cost of this sweep is considerable. It’s hard to know what to expect of DC going forward, though. Can we perhaps read some silver lining into this storm cloud? Interestingly, DC editorial will be run by two women (for the first time ever?), Marie Javins and Michelle Wells, the latter the head of DC’s Young Reader division. And, as MacDonald speculates, it seems likely that “DC’s kids and YA books will be more important going forward.” I take that as good news—but I’m afraid the news for direct-market comic book shops doesn’t sound so good (see my recent reflection on that subject here). DC Publisher Jim Lee, who remains in place after the layoffs, gave an interview to The Hollywood Reporter last Friday that puts a bright face on the changes; it seems intended to be reassuring. But I’m not reassured. (See Heidi MacDonald and Rob Salkowitz for informed readings of that interview.) I am, however, guardedly impressed by DC’s current Young Adult line, despite initial skepticism and misgivings about the work continuing to be work-for-hire in the traditional DC way. This brings me to (forgive me for pivoting so sharply) a happy review of a newish book: You Brought Me the Ocean. By Alex Sanchez and Julie Maroh. Lettered by Deron Bennett. Edited by Sara Miller. DC Comics, ISBN 978-1401290818 (softcover), 2020. US$16.99. 208 pages. (BTW, this is the third in an occasional series reviewing children’s and Young Adult graphic novels from DC. See the first here and the second here.) You Brought Me the Ocean is a smart, beautifully rendered queer YA romance in the guise of a superhero origin story, and a whole, rounded novel to boot. Despite being set in a desert town, it’s about water, about the ocean, and about learning to live as an “amphibian” in a mostly dry world. There’s something about Aquaman in it, and Superman does a distant fly-by, but, really, this story belongs to young Jake Hyde, his lifelong friend and neighbor Maria Mendez, and the young swimmer Jake falls in love with, Kenny Liu. (Jake is basically a new take on the Young Justice version of Aqualad, for those keeping track.) Kenny opens new doors in Jake’s life, just as Jake has to contemplate leaving home for college and a complex shift in his relationship with Maria. Fittingly named, Jake Hyde is closeted in several ways—in fact he is an unknown even to himself—but the story represents his coming out and coming into his own, folding together hero-origin tropes with high school and romance conventions. Loved ones and bullies alike exhibit homophobia—but, with the exception of one foul thug, the major characters all reveal unexpected depths and changeability. Characters disappoint, but then happily surprise. As Jake realizes his powers—the reason for the strange, scar-like markings on his skin—he, Maria, and Kenny become a triad of friends, and the denouement is wish-fulfilling but not pat. (There could and should be a sequel.) If Ocean revisits some familiar stuff—protective or disapproving parents, homophobic bullies repping toxic white masculinity—its characters are distinct and nuanced, and have humanizing touches. Further, the familiar stuff feels pretty convincing: these aren’t cliches so much as things that commonly happen and should be acknowledged. The book has a confident sense of its characters from the first; I can believe, for example, that Maria and Jake are longtime friends, with a shared history and personal language. Their interaction feels real enough. Scriptwriter Alex Sanchez (Lambda Award-winning author of the Rainbow Boys trilogy) handles characters and world deftly, with a smart, unforced touch. And artist Julie Maroh (Blue Is the Warmest Color) seems to know these characters’ physicality—their carriage and body language—as well as an artist could. Maroh’s figures are compact, sensual, and expressive. Most importantly, they are distinct. You Brought Me the Ocean benefits from a unified aesthetic that is unusual for DC Comics. Bathed in watery blue and silver-gray, and then again in muted desert browns and tans, the book enacts the major conflict in Jake’s life through its very palette. Thanks to Maroh and designer Amie Brockway-Metcalf, it boasts a visual wholeness and integrity that set it apart. Subtle yet dynamic layouts, unhurried pacing, and mostly understated action define the book, which sidesteps epic superhero dust-ups in favor of smaller, though still dramatic, discoveries. That said, the art remains ravishing; Maroh’s individualized figures and muted colors cast a spell even as they do the vital work of characterization. This appears to have been a harmonious, lovingly edited collaboration; it’s a remarkable feat for a first-time team. As I said, I’d read more. You Brought Me the Ocean is YA superheroics done with grace and a sensuous visual language. In fact, it’s only a superhero story on its edges; fluency in the DC Universe is not required. At heart, it’s an affirming story of love and friendship with a fantastical, magic-realist touch. Recommended! PS. KinderComics is taking a roughly six week-long break, sigh, so that I can start the new semester at CSU Northridge more or less sanely. See you in about a month and a half!

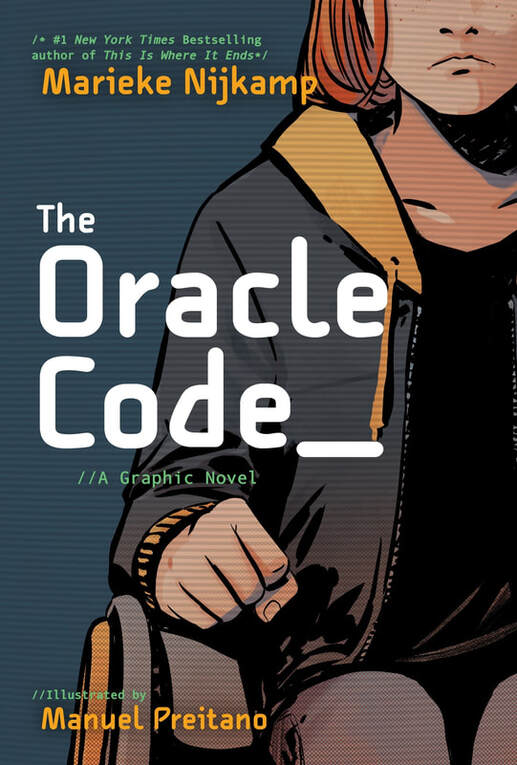

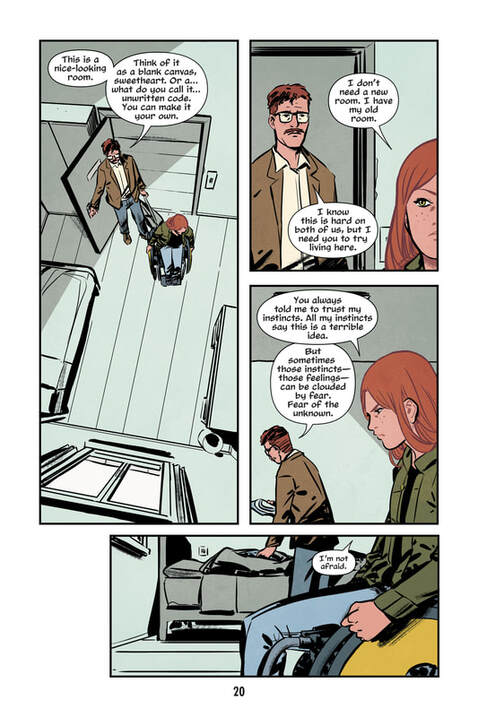

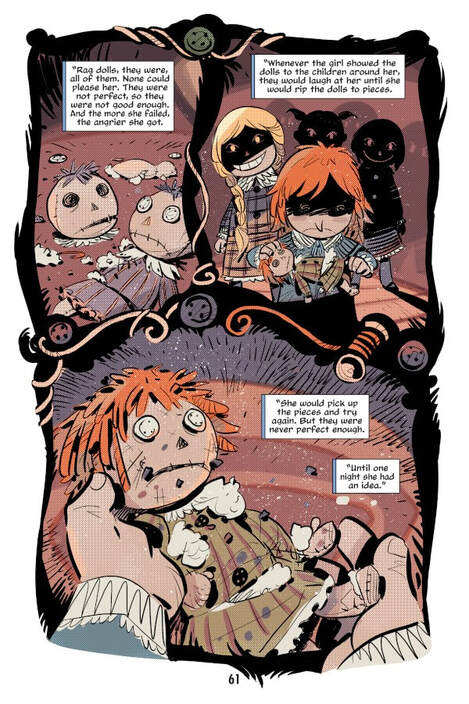

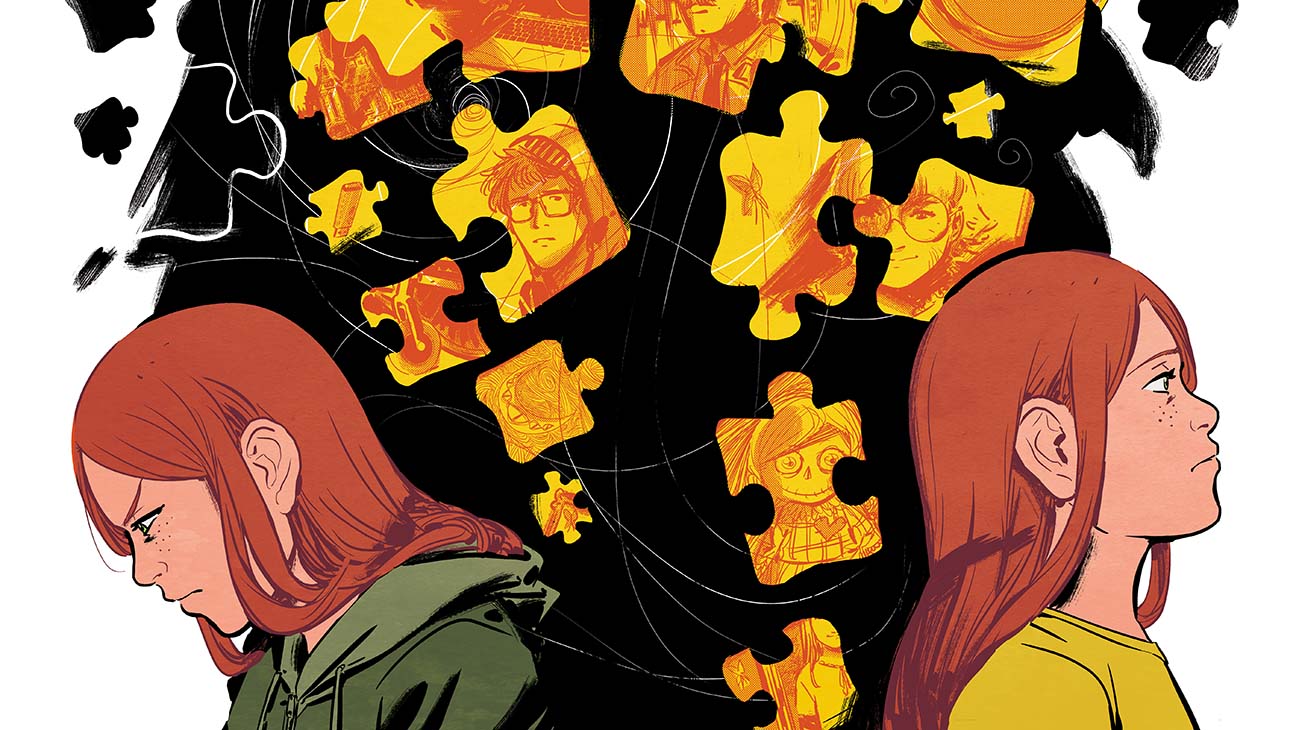

The Oracle Code. Written by Marieke Nijkamp; illustrated by Manuel Preitano; colored by Jordie Bellaire with Preitano; lettered by Clayton Cowles. DC Comics, ISBN 978-1401290665 (softcover), 208 pages. US$16.99. March 2020. (This is the second in an occasional series reviewing children’s and Young Adult graphic novels from DC. See the first here.) Paralyzed by a gunshot wound, brilliant young hacker Barbara Gordon (daughter of Gotham’s police commissioner) undergoes rehabilitation at the so-called Arkham Center for Independence — which, surprise, turns out to be a sinister place, a haunted house even, from which patients keep disappearing. Though traumatized, and at first resentful and alienated, Barbara gradually bonds with other patients, and together they form a team to unravel Arkham’s dark secret. This DC graphic novel does not appear to mesh with any version of DC continuity, and its Barbara Gordon differs sharply from previous Barbaras (Batgirl or Oracle). In fact, its DC-ness is nominal, and could be erased with a few minor edits. It’s not a superhero story in the usual sense. Rather, it’s a Young Adult thriller that follows many of that genre’s conventions: young people up against corrupt adult institutions, fighting with official powers, fighting for self-definition, testing their mettle with no outside help. It’s also grounded in an intersectional and community-oriented disability politics that makes it stand out among DC books. Writer Marieke Nijkamp is an acclaimed author of YA thrillers (e.g., This Is Where It Ends), editor of a disability-themed YA anthology (Unbroken), and advocate for greater diversity in children’s and Young Adult publishing (she served as a founding officer of We Need Diverse Books). The Oracle Code’s plot seems to have been informed by her experience living in a medical rehabilitation facility as a teenager. Her loner hero, Barbara, eventually enters into community, and, with her team, emphatically rejects the idea of being “fixed” (echoing Nijkamp’s criticisms of the trope of curing disability). The book’s politics are obvious and central, and some minor characters and relationships seem designed to make points — or to serve merely as hurdles to Barbara’s ferocious drive. The plot, I think, rushes to a too-sudden conclusion; I can see the story’s somewhat familiar shape from far off. Barbara herself, though, is a distinct character, and the book gives her time and space to be properly angry. If the book preaches, it doesn’t preach to Barbara. Also, the wrap-up wisely lets certain resolutions stay ambiguous; this is no facile overcoming narrative in which all things are made better. The book reflects on the healing value of dark stories — through a series of unsettling embedded tales, like bedtime stories — and itself does not shy away from trouble. The Oracle Code, in sum, is a designedly Young Adult novel that reflects and capitalizes on the disability politics always implicit in the Oracle character. Visually, The Oracle Code wavers between arid daytime plainness — perfect for a medical facility — and darkly atmospheric nighttime scenes. Illustrator Manuel Preitano favors a naturalism that, for me, recalls the post-Mazzucchelli work of David Aja (though without Aja’s drastic stylization and formalist invention). The intentionally limited color palette (colors are credited to both Jordie Bellaire and Preitano) pits vivid yellow-orange and nocturnal purple-blue against drab olive and icky, hospital-bland greens. Insipid, textureless rooms — like the flat, medicalized interiors we all know, presumably lit by fluorescents — clash with densely shadowed scenes defined by slashing swathes of black and vigorous dry-brush technique. Bright jigsaw puzzle pieces stand out against the general gloom and serve as a braided visual device: a multivalent symbol that variously signifies trauma, fragmentation, reassembly, accomplishment, and, of course, mystery-solving. The layouts are dynamic, shifting, yet steadily rectilinear, except for the embedded “bedtime” stories, which boast curving, swirling panel shapes and a contrasting, cartoonish style. This novel is, as far as I know, Preitano’s longest sustained work for the US market (he has also worked on the series Destiny, NY and several comics for Zenescope), and departs from the sometimes lurid retro aesthetic of his illustrations for the Vaporteppa fiction line, in his native Italy. This looks like a big step forward for the artist. On balance, The Oracle Code shows the potential of YA fiction that happens to be set in DC’s story-world. It’s more self-contained, and more attuned to the conventions of YA fiction, than I had expected. To me, these are good things. One thing gets to me, though: despite the signs that this book is a rather personal work for Nijkamp, it is copyrighted solely in the name of DC Comics — that is, it’s work for hire (though it bears about as much resemblance to prior Oracle stories as, say, Neil Gaiman and company’s Sandman bore to prior Sandmen). I think that’s a shame, and, honestly, this is one reason I have not been able to muster great enthusiasm for DC’s work with YA and children’s authors. As long as DC graphic novels are centered on company IP and the creators are wholly dispossessed of any equity in the work, as long as DC persists in these damaging comic book industry practices, the promise of its young readers’ line will be dampened. The Oracle Code is very unusual for a DC comic — its focus on a non-superpowered community of young women, and willingness to highlight a young woman’s anger and power, are laudable — but it’s still shackled to DC’s old way of doing things.

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed