|

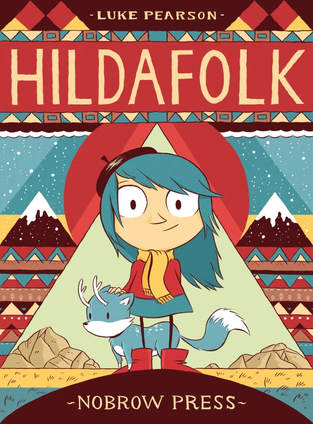

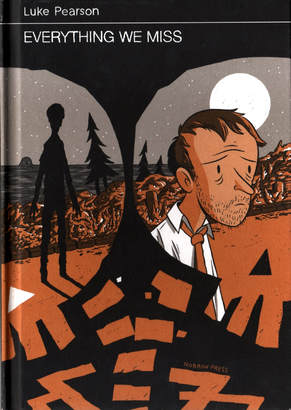

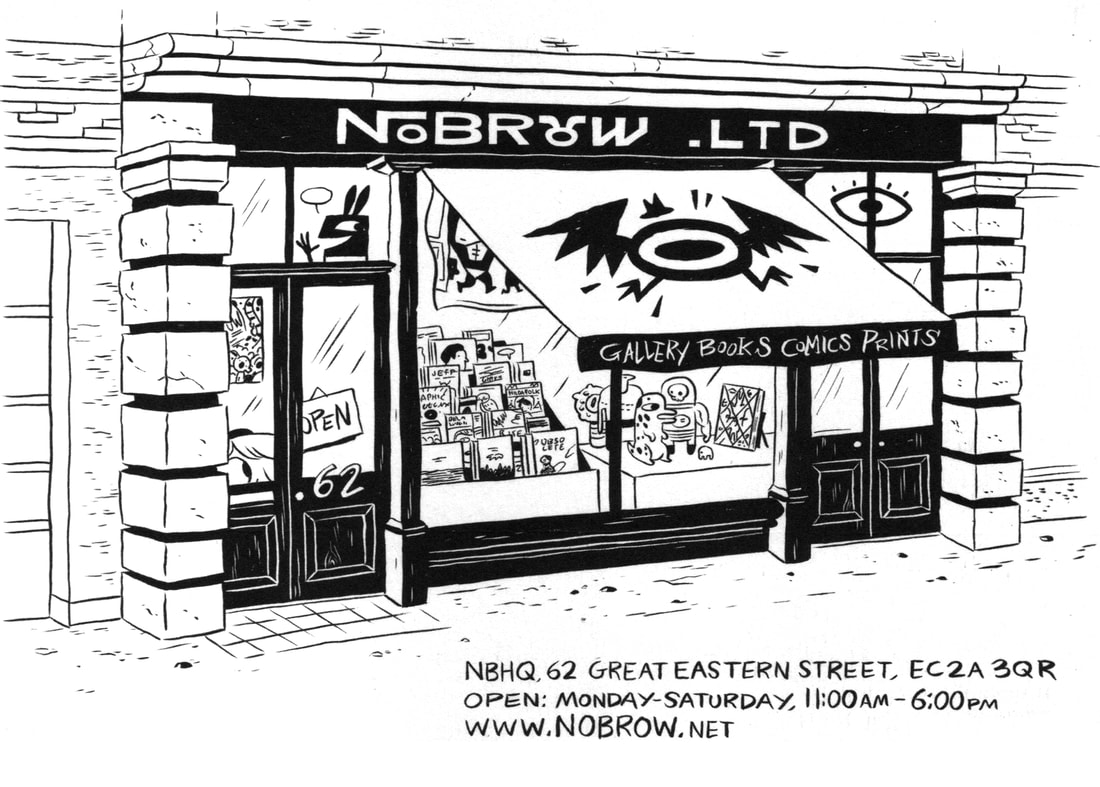

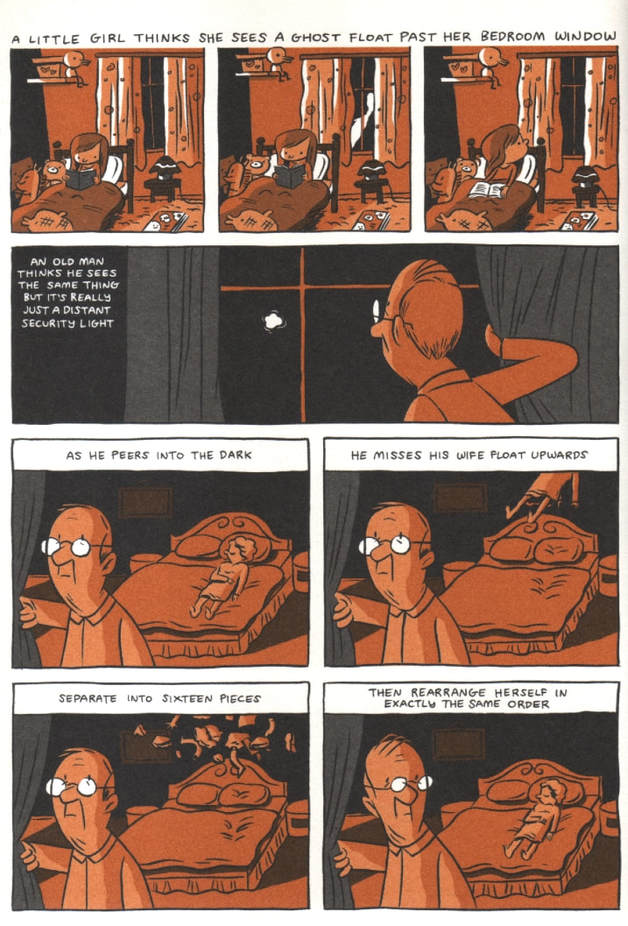

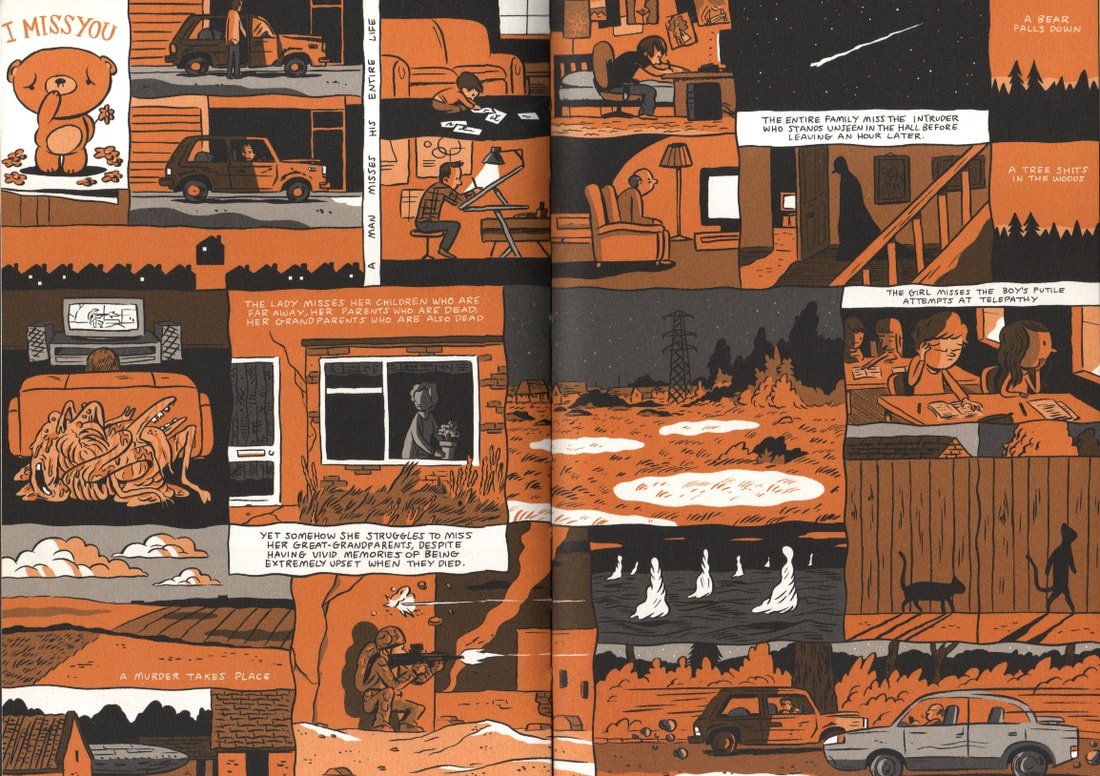

Being a series on one of my favorite cartoonists I first encountered cartoonist Luke Pearson’s work about eight years ago, in a curious, frankly mismatched pair of books, both put out by the London-based boutique publisher Nobrow. The first of these was Hildafolk (2010), a charming 20-page vignette in the form of a full-color, saddle-stitched pamphlet. Hildafolk was part of Nobrow’s 17x23 series (so named for its dimensions, in centimeters)—think of it as a sort of exalted floppy. A child’s adventure, it ended oh so quickly, but suggested a world of further adventures lying in wait. Little did I know: this was the project that would turn out to be the hub of Pearson’s career, to date. The second book, Everything We Miss (2011), was emphatically something else: a melancholy visual poem about loss, loneliness, and our capacity for blind self-absorption, in the form of an even smaller (15.5 x 22 cm) hardcover of 40 pages. I rediscovered Everything We Miss on my shelves the other day: a compact book in an odd palette of black, grey, and two vivid shades of orange. It’s quite sad, and very much an alternative comic for adults. Both books are beautiful—and it was the combination of the two, rather than either of the books on its own, that clued me in to Pearson's talent. I owe my encounter with these books to a family sojourn in London in summer 2011, and particularly to the splendid comic shop Gosh! (then still in its Bloomsbury location, opposite the British Museum, as opposed to its current space in Soho). These are the books that introduced me to Nobrow—these, and then Ben Newman’s Ouroboros (another 17x23 pamphlet), and then Jon McNaught’s two small, gorgeous hardcovers, Birchfield Close and Pebble Island. As I recall, it was Pearson’s work in particular that inspired me to seek out the Nobrow shop (then located on Great Eastern Street in Shoreditch), a visit I recall fondly. I’ve been fairly smitten with the Nobrow brand since. Of the two Pearson comics I discovered in 2011, Hildafolk struck me as the more delightful, while Everything We Miss seemed the more determinedly “serious.” When first I read Everything We Miss, I thought of Chris Ware, not for drawing style so much as a strange combo of formal knowingness—that is, a kind of designing aloofness—and terrible poignancy. In part, Everything We Miss is about watching people suffer. But on re-reading, I think less of voyeuristically peeking into people’s suffering, and more of the poignancy. Also, the style, I now think, bespeaks Seth or Kevin Huizenga more than Ware, with something of Huizenga’s penchant for quiet unease and perhaps sadness, but also wonder—all this, again, allied to an ingenious formalism. Re-reading the book, I also recognized a vein of sly humor, via Pearson's low-key sifting-in of bizarre details. Essentially, Everything We Miss depicts the sad, crumbling end of a couple’s relationship, but also their inability to see other people’s lives—and a host of peculiar, startling things—going on around them. Trees dance; bodies break apart and reassemble; asteroids nearly strike the earth. The estranged lovers do not notice. Their obliviousness stands in for human obliviousness in general, as the book's roving eye makes plain: Meanwhile, braided visual metaphors lend heft and quirkiness to an otherwise despondent story: Shadow-shapes filter in and out of people’s bodies, grabbing at their mouths, their brains. Odd, semi-crustacean creatures observe human doings from the neglected corners of our everyday spaces, always slipping just out of sight. A two-headed skeleton (reminding me of Ware’s “Quimbies the Mouse”) graces the first page and the last (and, implicitly, the cover). Is this a metaphor for the couple's dying relationship, as opposed to either of the two individuals who made up that relationship? And/or for the miraculous, sometimes grotesque details of the world that continually escape us? The book closes ambiguously, with a near-suicide that ends in continued living—though whether this is a matter of life clinging to life, or life hanging on desperately to something that’s already dead, is hard to say. The willed darkness of the story seems indebted to other alt-comix, though Everything We Miss has its own muted shocks, and own loveliness. The book seems to turn on a pun that conflates "missing" in the nostalgic sense (that is, pining away: I miss you) with "missing out" in the sense of failing to notice, or failing to take part in, the world. The climactic spread points out this double meaning with a mix of details both sublime and trivial, and in a tone that's hard to peg, at once melancholy and whimsical: A bear falls down / A tree shits in the woods. Self-reflexively, the spread seems to point to Pearson's own cartooning as a habit that may cause him to miss "his entire life" (a common concern among cartoonists: see Pearson's Ware- and Huizenga-like map of his working environment, from Solipsistic Pop #4, 2011). Meanwhile, ghosts and marvels abound, quiet places reserve dark secrets, and half-glimpsed mysteries impinge on mundane life: A panel about a lady missing her family borders both a panel of, apparently, warfare, and another panel of someone perhaps watching the same warfare on TV. This domestic pathos, rather Ware-like, borders monsters and prodigies. The resulting spread is funny, yet sad. It's hard to tell whether Pearson's tone is a surrender to the familiar alt-comix vibe of melancholy and isolation, or a rejoinder to it: a reminder to open one's eyes and engage the world, in all its teeming strangeness. The anxiety feels genuine enough (and anxiety does come readily to Pearson: check out, e.g., this comic, or this one). I like the way the layout here reinforces the tonal ambivalence: the spread might be read as three more or less even tiers stretching horizontally across the page gutter, but for uneven borders that confuse our linear progress, jumbling the flow as we approach the bottom right corner. All this leads to a suggestive final panel that depicts our would-be suicide driving away, away, toward the page turn. The fantastical quirks in Everything We Miss – the bizarre critters and happenings just beyond human sight – live on in the brighter world of Hilda, with its matter-of-fact approach to mystery and magic. Hilda has become Pearson's calling card: thus far he has created four further Hildafolk albums (2011-2016), with more in the works. He has done a wealth of other things too (his website is, no kidding, a trove), but it's Hilda for which he's best known. In fact, since Nobrow launched its children's imprint, Flying Eye Books, in 2013, Hildafolk albums have become one of that imprint’s best-selling mainstays. And now, of course, there’s something else: an animated adaptation of Hilda has just joined Netflix’s lineup of original animated children’s series. As of September 21, it’s been possible to view the first season of Hilda, all thirteen 24-minute episodes, in Netflix’s usual bingeing way. Co-produced with London-born Silvergate Media and Ottawa animation studio Mercury Filmworks, this Hilda series involves Pearson as credited creator, co-executive producer, and occasional episode writer. That alone was enough to nudge me into renewing my lapsed Netflix account—and to inspire me to gather my Hildafolk albums into one place, the better to reread and review them. They warrant it. Bookmark KinderComics, then, for a series of posts that I’ll call “Reading (and Watching) Hilda.” This series will cover Hilda in print and on screen (including the just-published novelization of the TV series, by Stephen Davies). Stay tuned!

1 Comment

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed