|

This has been a fallow year for KinderComics. I've been fairly out of touch with new comics for young readers, not because the field isn't thriving (on the contrary, children's and young adult graphic novels are still mushrooming like crazy) but because of other factors I don't think I'll write about here. Suffice to say that both hard things (losses in my family) and good things (new opportunities for work) have diverted my attention. I have been reflecting and readjusting. I continue to fight the urge to close up shop and declare KinderComics a done deal. I'd hate to do that. Yet I don't know when or how I can get back to writing here, with so many other things piled on my plate. I've worked up a list of favorite comics from the past year, a sort of Top Thirteen (baker's dozen), which is part of The Comics Journal's Best Comics of 2022. It doesn't include any children's or YA work, though. I can see that my interests have been shifting. With all this in mind, I am declaring KinderComics on indefinite hiatus, once again. Sigh. PS. I'm working on two books, one near-term, the other a bit farther off. And I'm designing a seminar about Marvel for the coming semester. So, work continues.

1 Comment

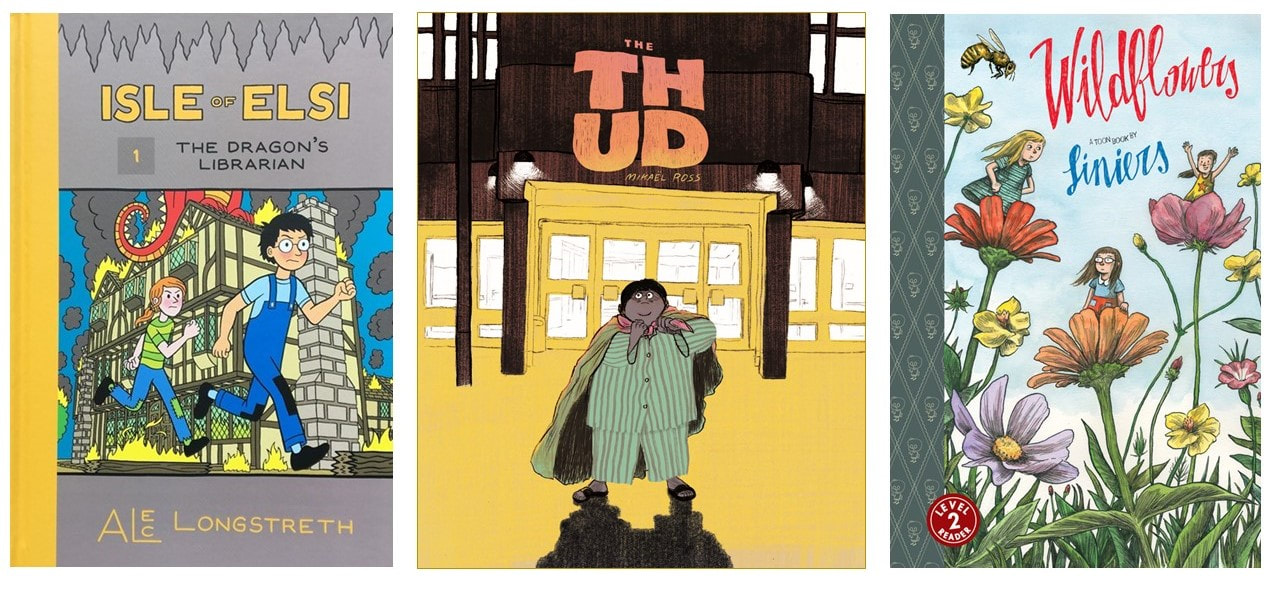

Regretfully, I must announce that KinderComics is on indefinite hiatus. I'm not sure what this means, exactly, but I do know that I will post few if any reviews here from now until the end of the academic year (so, June 2022), and nothing big. Worse, I can't be sure that I'll be returning even after that. As an academic, meaning a teacher first, scholar second, and critic third, my yearly cycle is keyed to the traditional school calendar, which for me equals August through May. During those months my hands are full, and these days I feel an ever-greater pressure to devote summers to the scholarly projects and teaching prep that I cannot get done during the other nine to ten months. I know that something, some things rather, have to give, and, sigh, KinderComics seems to be one of those. For the past three and a half, going on four, years, this site has been my pride and joy. I've enjoyed writing here, and putting myself to work thinking about some great comics. Yet I know this site has never been able to sustain real momentum, not enough for KinderComics to become a known and trusted source for reviews; that has been a source of regret. I haven't been able to get out in front of new book releases, to be timely as reviewers tend to be. And I've never been able to expand this site beyond reviews to interviews and longer features as hoped; again, regrets. So, not once but repeatedly, I've been forced to admit that this is an extracurricular pursuit of mine, squeezed in between the other aspects of my working life. I should admit that something else is going on too. I'm writing this through a fog of bereavement, as both my mother, Ella Jane Ellington Hatfield, and my father, Jerry Hatfield, have passed since midsummer. I've experienced their deaths as sudden shocks to the system; I seemed to have been turned upside down and inside out. I find myself wanting, needing, more time than I have. I feel a need to refocus. Since I have several long-range projects in the works (here's one), and since there ought to be more to life than sprinting to catch up on my comics reading, I need to take a break, somewhere. Here, I'm afraid. The thing is, writing reviews is my favorite form of writing. I like the elasticity of it, the freedom of writing less formally and at different lengths. I love concentrated encounters with works of art that interest me, and I like the more or less constant practice of writing for a blog. Also, I like staying in the swim when it comes to comics, especially young readers' comics. That matters to me. KinderComics was created to satisfy all those itches. So, to press the Pause button on it, with the thought I may never be able to unPause it, that's a blow. But I'll continue writing occasional criticism for the excellent SOLRAD: The Online Literary Magazine for Comics, and I hope for The Comics Journal too, my two favorite platforms for online comics criticism. Those trusted online magazines have been an outlet for me, and I can write for them without spending much time on social media trying to draw eyes to my work; I look forward to continuing with them when I can. Readers, I hope you'll look for my work there, and thanks for listening. If I get back to writing here, I'll sound the trumpets! In the meantime, this site is staying up for the foreseeable future. If you see something here that sparks your thinking, and you want to reach out, use the Contact form, above! I'd be glad to chat.  PS. Back in September, I described Sas Milledge's comic book miniseries-in-progress Mamo as "a warmly humanistic, implicitly queer-positive, inclusive fantasy" and "an aesthetic delight." Now that it's done, I can strike the "implicitly" from the above, and can also affirm that the finished story is just as strong as I hoped it would be. Highly recommended; I bet there will be a trade collection soon! Milledge is one of the great talents I've learned about thanks to KinderComics (good god, Kat Leyh, Jen Wang, Rumi Hara, Jerry Craft, Molly Knox Ostertag, Chad Sell...). I'll look out for whatever she does next. News: I'm glad to have found a new connection and new venue for some of my writing about children's and young adult comics: SOLRAD, the online literary magazine for the comics arts. SOLRAD, published by the nonprofit Fieldmouse Press, is the work of a dedicated editorial team and a burgeoning community of artists and thinkers. Since launching in January 2020, it has offered comics journalism, criticism, new comics, and an inclusive space. Recently I've been publishing reviews with SOLRAD under the KinderComics tag, with particular help from publisher Alex Hoffman, editor-in-chief Daniel Elkin, and acquiring editor Rob Clough. I'm proud to be working with them. I've published three KinderComics posts with SOLRAD so far: reviews of Alec Longstreth's Isle of Elsi: The Dragon's Librarian (January), Mikaël Ross's The Thud (April), and Liniers's Wildflowers (May). Each has been a learning experience and a pleasure, and each has benefited from eagled-eyed editing by Team SOLRAD.  I hope and plan to write regularly for SOLRAD. It may become my main venue for children's and YA comics reviews. I'm not sure yet. Suffice to say that I've been craving a new venue, one that could draw its own loyal audience. I've been wanting new ways to get my comics reviews out into the world. KinderComics was born in 2011 as a column at The Comics Journal (tcj.com), a site and brand I've loved for years that remains dear to me. However, I stalled out there, unable to find a rhythm. Years later, this blog, KinderComics.org, revived the idea, and for the past three years it has been a joy to write in this space — but then again a frustration when other work got between me and the blog, causing me to lose the momentum needed to sustain a good-sized readership. Given my academic work, I'm afraid I cannot post weekly. Nor have I been able to post the kinds of interviews and longer features I dreamed of. I've come to realize that I need to be in the company of other writers and partnered with a group that has its own momentum. With that in mind, as I mull over what to do here at KinderComics.org, I'd like to invite you, my readers, to follow me over to SOLRAD (if indeed you don't already have SOLRAD bookmarked!). Whether to put this blog on hiatus or not is a decision I won't make until sometime after I publish my next review in SOLRAD (in the next few weeks). I may use this space to post brief capsule reviews or some kind of semi-weekly reading journal. Again, I'm not sure. In the meantime, I'm delighted to be working with the SOLRAD team!

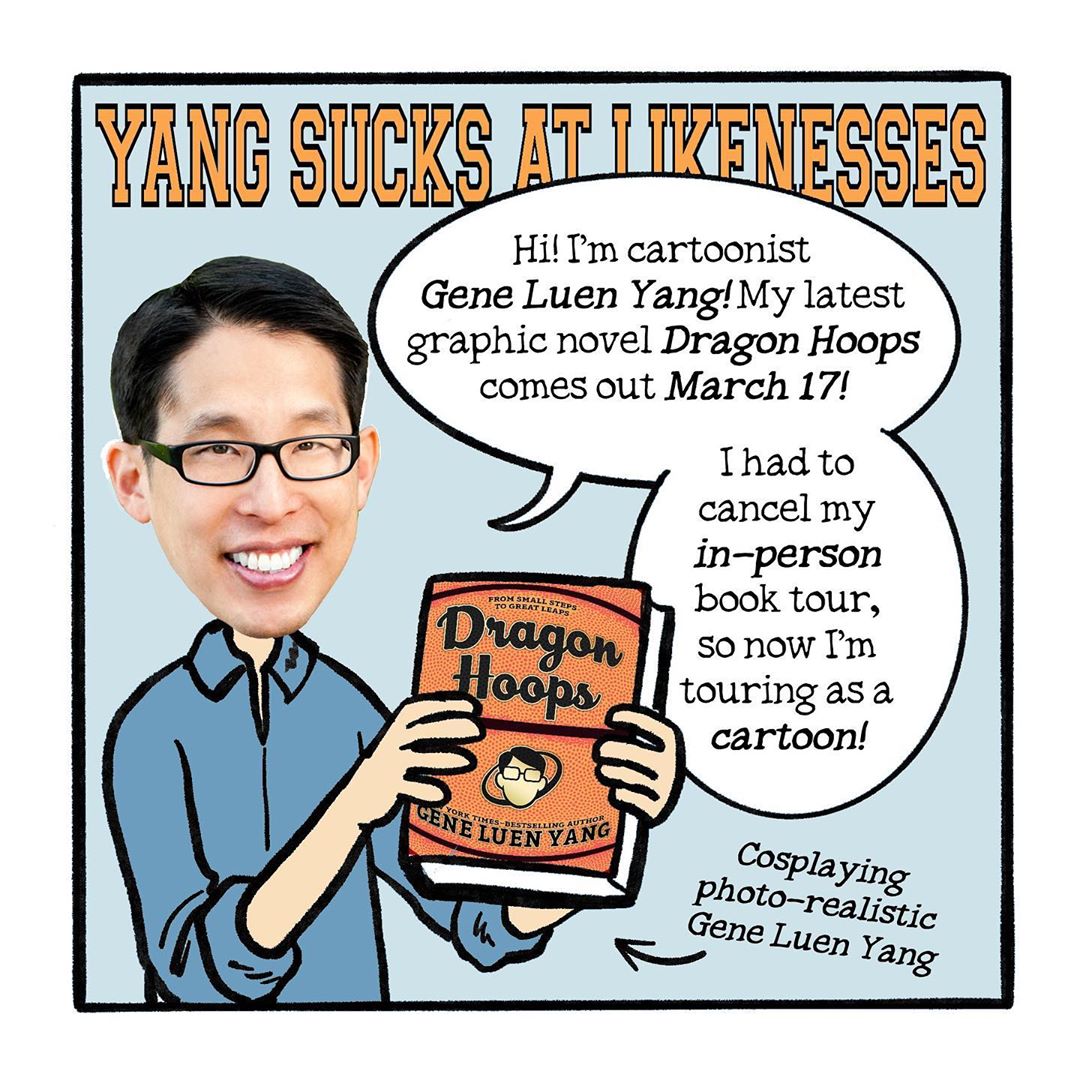

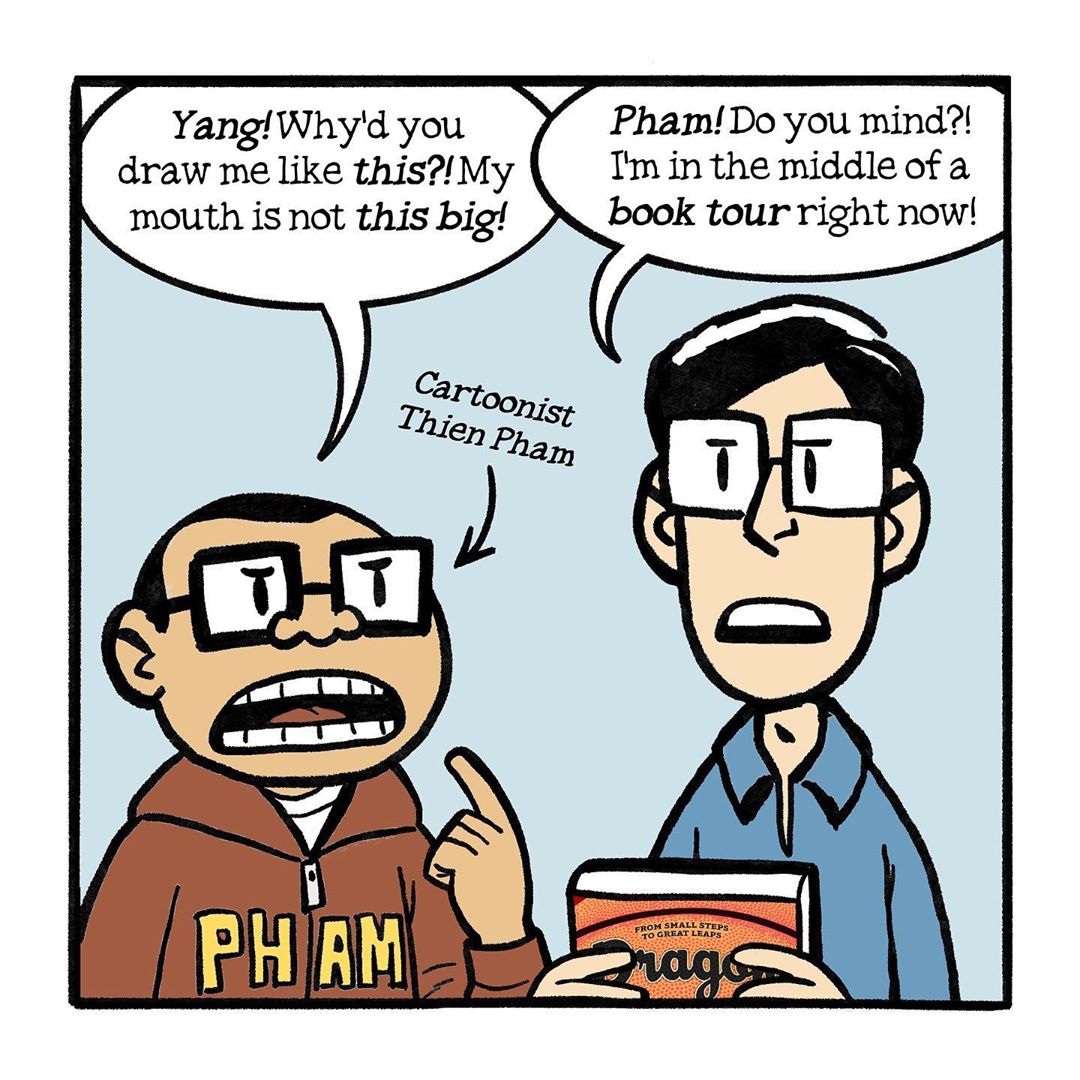

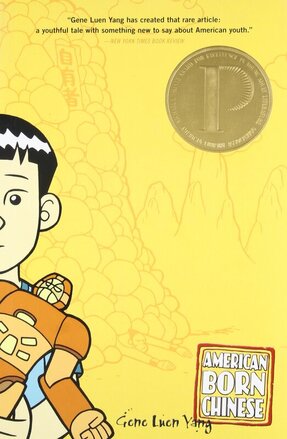

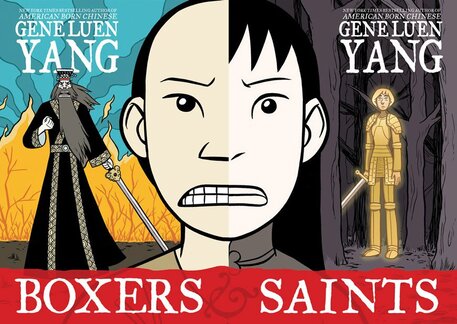

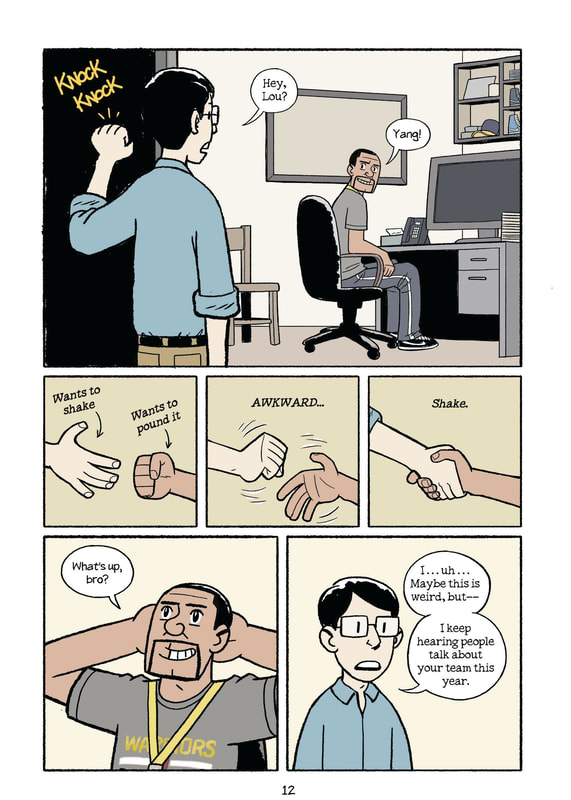

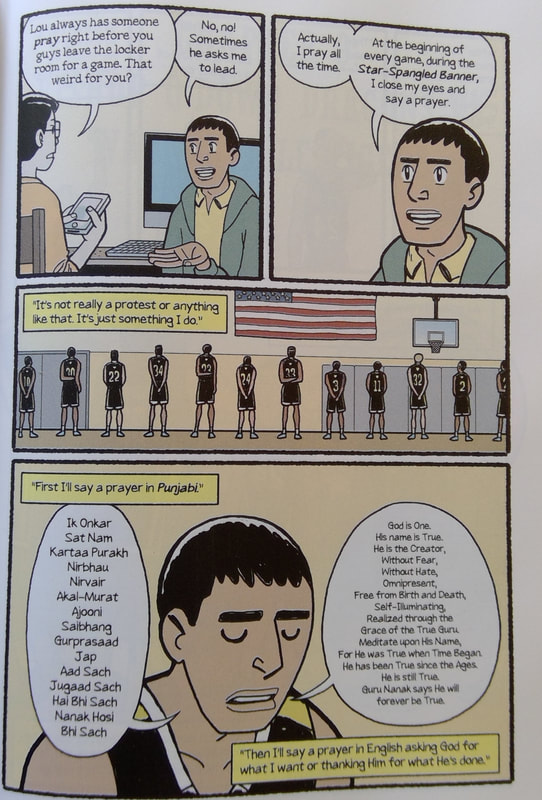

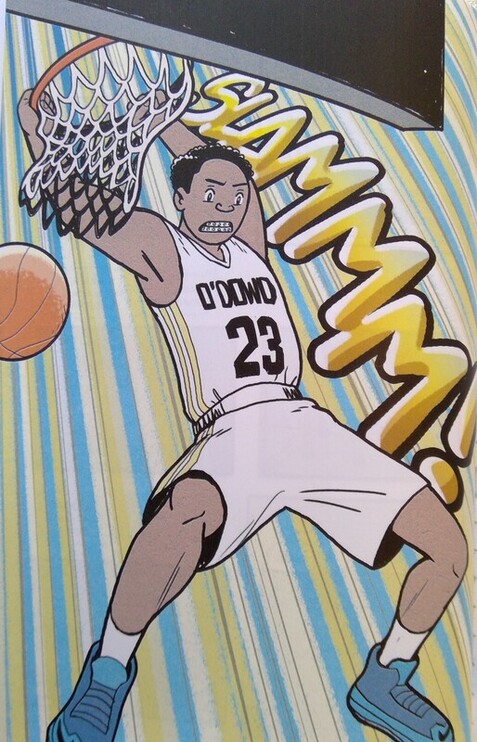

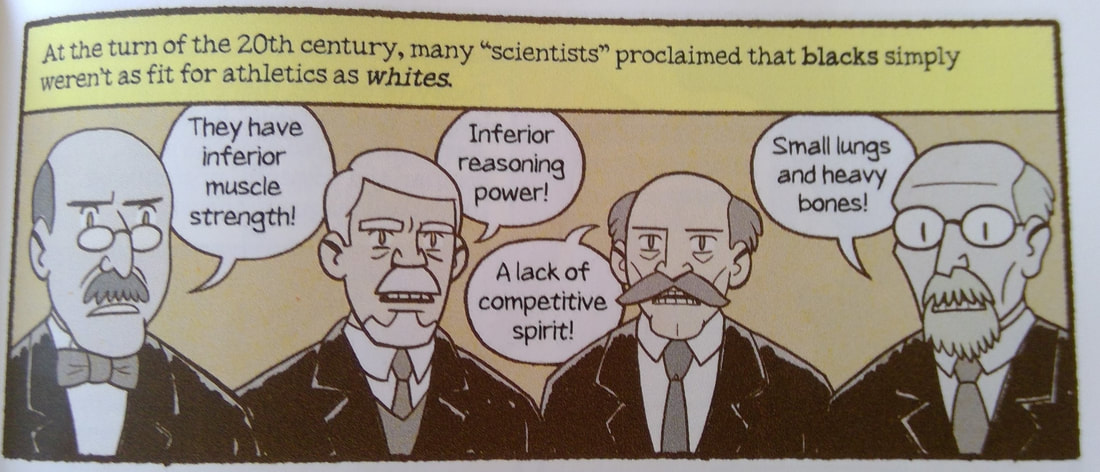

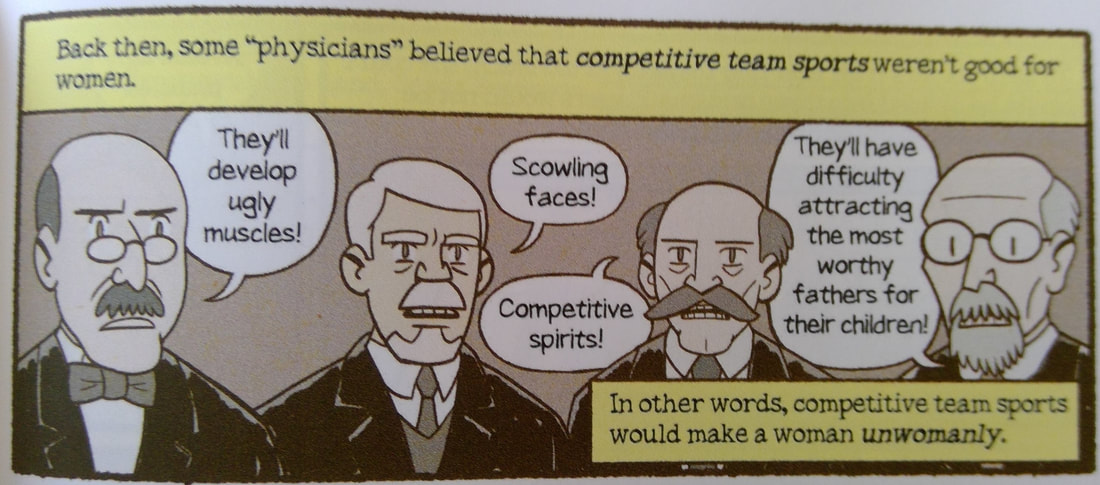

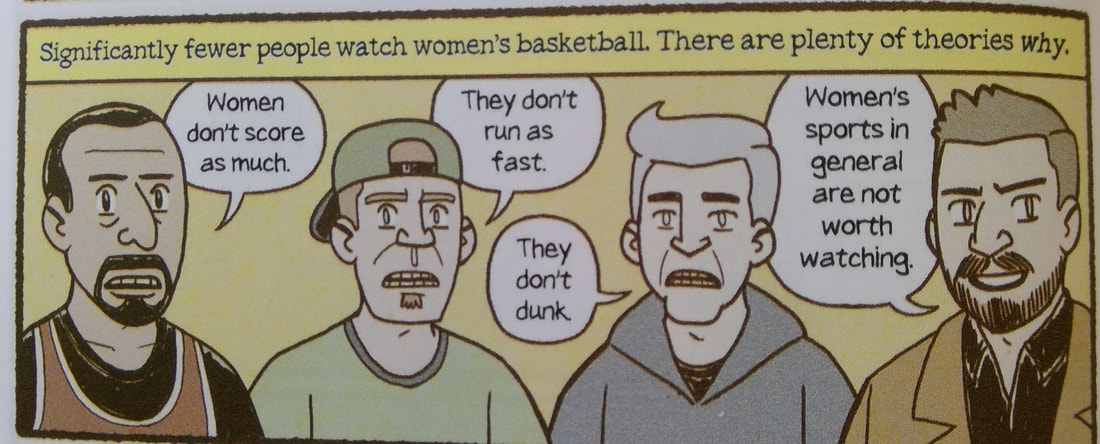

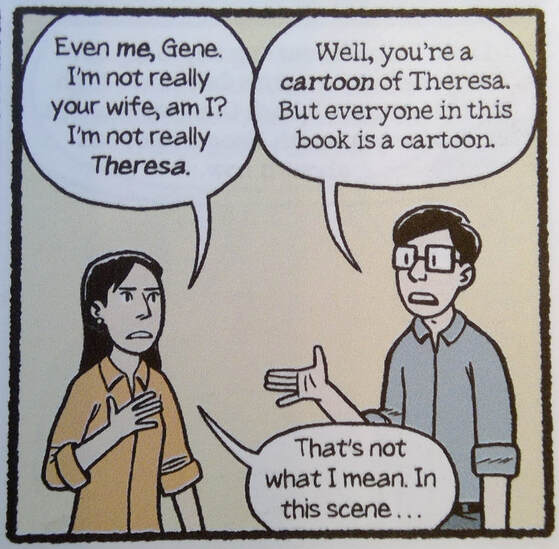

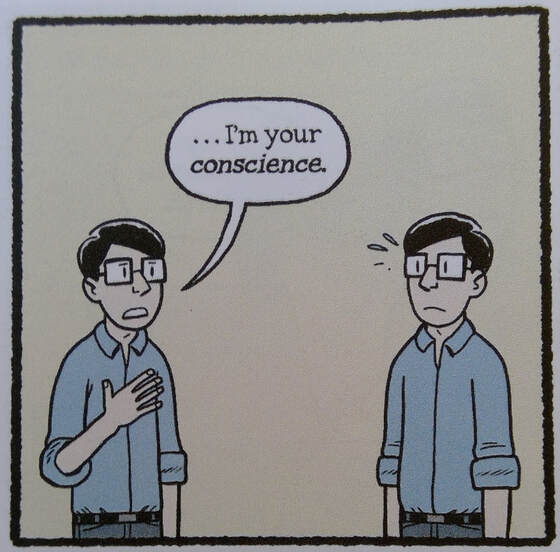

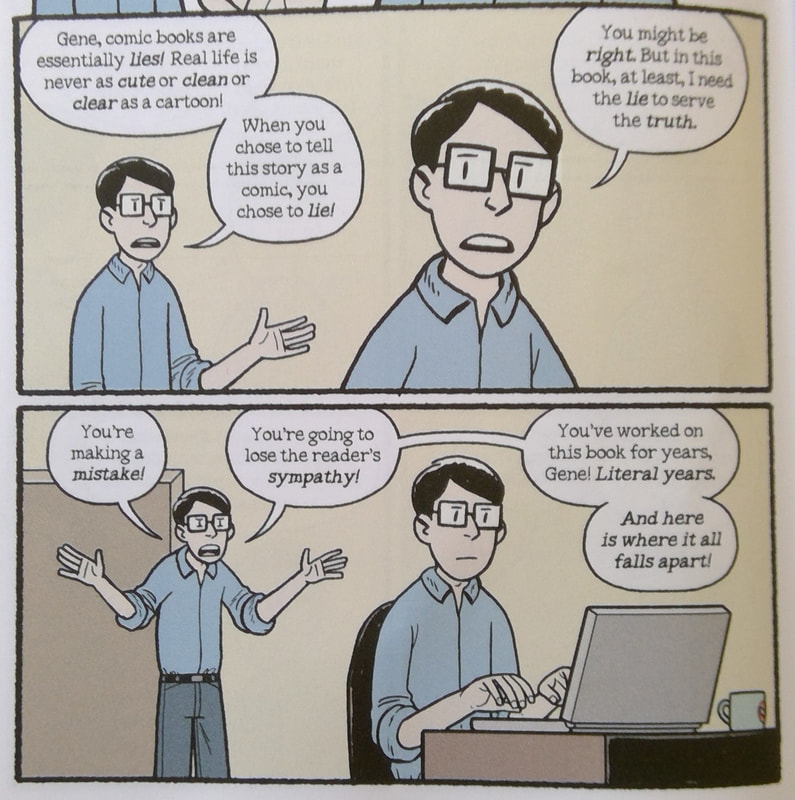

Dragon Hoops. By Gene Luen Yang. Color by Lark Pien. First Second. ISBN 978-1626720794 (hardcover), $24.99. 448 pages. March 2020. Recently Gene Yang has been out touring in support of his newest graphic novel, the just-released Dragon Hoops. But of course he hasn't been touring in the flesh; the COVID-19 pandemic has had him—like so many of us—holed up at home, trying to find creative new ways to engage with both his family and his public. Happily, he hit upon the idea of a virtual book tour: that is, promoting Dragon Hoops through a series of Instagram comic strips in which he responds to readers’ questions. These quick comics are formulaic, but the formulas are clever and engaging: Yang repeats shots and gags across the series, making it feel much like whistle stops before a loving audience that tends to ask the same few questions again and again. Of course, these comics are self-deprecating—more than anyone else, Yang is the object of his own jokes. He makes an excellent comic strip character. Humorous self-deprecation is one of Yang’s constants. He used to self-publish under the imprint Humble Comics, and if you’ve seen him speak you know that he excels at genial self-mockery. Yang plays humble the way Liszt played the piano—it’s his instrument. But don’t let him fool you: he is a gutsy and ambitious narrative artist whose work walks a tightrope between charming accessibility and willed difficulty. Yang takes chances. In particular, his solo graphic novels (as opposed to his many collaborative works) are fearsome high-wire performances. Dragon Hoops is no exception. Yang’s comics tend to be structurally tricky, thematically bold, and psychologically sharp. His breakout book, American Born Chinese (2006), semi-autobiographical yet fantastical at once, interweaves three stories in three different genres, until a startling moment that turns those three tales into one. The novel oscillates between ingratiating humor and terrible pain (in fact, those two tones are co-present throughout). Mixing myth fantasy, earthbound middle-grade school story, and arch sitcom, American Born Chinese is great comics, capitalizing on the form’s stable-unstable, multimodal heterogeneity to tell an immigrants’ son’s story, one of divided identity or fractured self. At bottom, it’s a story about internalized racism and self-hatred. A nervy book, it freely adapts China’s legendary Journey to the West, while at the same time insinuating a Christian allegory and riffing on Transformer/mecha pop culture. Moreover, it dares a form of grotesque satire, in which hateful, grossly racist anti-Chinese stereotypes reflect the protagonist’s self-loathing (a strategy as impious and risky as Art Spiegelman's notorious animal metaphor in Maus). In sum, American Born Chinese revealed Yang’s propensity for large-scale structural conceits that enact his own ambivalence and complex sense of identity. It was, is, daring. Yang’s follow-up project, Boxers & Saints, goes one better. A two-volume novel about China’s Boxer Rebellion, it’s a magic-realist historical fantasy in which the twin volumes represent, in a kind of tense counterpoint, both Chinese nationalist (Boxers) and Europeanized missionary (Saints) perspectives. Pitting the story of a young man who is an anti-colonial revolutionary against that of a young woman who is a Christian convert, Boxers & Saints balances Yang’s Catholicism against his pained awareness of Western imperialism and racism, while also critiquing strands of misogyny in traditional Chinese culture. The resulting two-headed novel, rather shockingly violent for Yang, represents a dramatic argument: a psychomachia in which different facets of Yang contend with each other, bitterly. Boxers completes Saints, and vice versa, and both volumes sting. This project shows, again, Yang’s penchant for teasing out self-conflict by counterposing different plots (in this case, different books!) and engineering complex structures. Identity in his books is as tricky as the plots: dynamic and never settled, an anxious balancing act. Yang's ingenious plotting, and an overall sense of high personal stakes, of storytelling wrung from pain, transform what could be flatly didactic into harrowing stuff. Dragon Hoops aims for this quality too, though it lacks the big structural conceits of the three-part American Born Chinese or two-part Boxers & Saints. It differs in another important way too: this time the tale is not historic, mythic, or crypto-autobiographical, but instead a literal memoir, an account of a year in Yang’s life as a teacher at Bishop O’Dowd High, a Catholic school in the Bay Area. Dragon Hoops is the longest overtly autobiographical work Yang has done. Yet it’s really about (huh?) basketball: on one level, Bishop O’Dowd’s varsity men’s basketball team, the Dragons, hungry for a state championship, but more broadly the entire history of the sport and how it intersects with race, class, and even Catholic schooling. In short, Dragon Hoops takes on basketball as a social force. This is something that the book’s version of Gene, archetypally geeky and sports-averse, has to struggle to understand. The story follows Gene from standoffish sideline observer (he is, at first, simply a storyteller looking for a new story) to ardent booster of the school’s basketball squad. At the same time, it charts a major shakeup in Yang’s own life, and offers multiple stories of struggle and vindication if not redemption. Further, it explores ethical issues involved in coaching, mentoring young people, and even Yang’s own storytelling. In fact, Yang worries on the page about what he is doing on the page. Here the book seems boldest--or perhaps most vulnerable? Dragon Hoops is long and complex (at about a hundred pages longer than Boxers, it is Yang’s heftiest single volume). Somewhere between intimate memoir, journalism, and oral history, it profiles the players on Bishop O’Dowd’s team, observes the complex social dynamics of their lives, and sets us up for, yes, a nail-biting climax on the court, at the longed-for championship game. Simultaneously, though, it recounts the creation and democratization, or broadening, of basketball, in a series of historical vignettes—while also depicting a transformative moment in Gene’s uncertain career in comics. That career comes to a sort of fortunate crisis when Gene, startled and uncertain, is offered a chance to write, of all things, Superman. Yang thus parallels the team’s story with a node of decision in his own life. In this way, the book explains why he is no longer at Bishop O’Dowd, and becomes a bittersweet valedictory to his seventeen-year stretch there (and perhaps a way of prolonging his connection to the school?). There’s a great deal happening in Dragon Hoops, then—the book’s seemingly straightforward structure conceals yet another gutsy high-wire act. This book is jammed full. Starting from a prologue in which Gene, reticent and awkward, seeks out Dragons coach Lou Richie, the story shuttles between present-day profiles and historical background, while also packing in loads of on-court basketball action. The team’s season, and Gene’s growing relationship with “Coach Lou,” are the spine of the book, but Yang freely intermixes other elements, with special attention to particular Dragons and how their team collectively embodies diversity. Chapters depicting important games alternate with chapters devoted to key players (in this sense, the book’s structure is very deliberate). Yang uses the players’ backstories both to celebrate basketball as an inclusive and egalitarian sport but also to point out various problems, notably racism and sexism, in the history and culture of the game. One chapter is devoted to a pair of siblings, Oderah, star of O’Dowd’s championship women’s basketball team, and her younger brother, Arinze, now part of the men’s varsity squad; the two are constant rivals, yet fiercely loyal to each other. Another chapter profiles Qianjun (“Alex”) Zhao, a Chinese exchange student on the Dragons’ team. Another focuses on Jeevin Sandhu, a Punjabi student of the Sikh faith—and here Yang focuses on the challenges of assimilation, while also providing, in effect, a brief introduction to Sikhism. There’s more. Dragon Hoops depicts James Naismith, who invented basketball in 1891; Marques Haynes and his fellow Harlem Globetrotters, who helped integrate the game; Senda Berenson, who launched women’s basketball; Yao Ming, the first star of Chinese basketball to thrive in the NBA; and other notables in the game’s history. Yang smartly interweaves present and past: the chapter on Jeevin also recounts the rise of Catholic schooling and the career of early NBA star George Mikan, a Croatian American player from a Catholic seminary; Yang then acknowledges that Jeevin, as a Sikh, is an outlier in Bishop O’Dowd’s Catholic culture (a scene of Jeevin reciting the Mul Mantar, a Sikh prayer, complements other scenes of praying in the book). Similarly, the chapter on Oderah and Arinzes weaves in Berenson’s story and the rise of the women’s game, including a historic dunk by pioneering college player Georgeann Wells. You can feel Yang matching up elements from past and present to build a tight, cohesive book. Visually, Dragon Hoops is likewise purposeful and designing. Breathless scenes of action on the court, sometimes parsed down to the split second, recall the sort of intense basketball manga popularized by Takehiko Inoue (Slam Dunk, Buzzer Beater, Real). These scenes attain an energy and forcefulness that exceed Yang’s previous work (even the martial violence of Boxers & Saints). There are sequences that fairly set my pulse racing. What makes these explosions of action thrilling is the way the book as a whole carefully measures out its storytelling, and uses the very controlled braiding of repeated imagery to reinforce its themes. Yang recycles and repurposes the same signal images over and over, to point up thematic parallels between past and present, among the different players, and between the Dragons’ quest for the championship and his own concern about going “all in on comics” as a career. Dragon Hoops is a library of key images, reworked and re-inflected (indeed, it could take the place of the vaunted Watchmen when it comes to classroom lessons about braiding!). In fact, it’s a brilliant sustained feat of cartooning for the graphic novel form; the book echoes back and forth, as Yang plays the long game. There’s a kind of nervousness, though, behind Yang’s cleverness. Dragon Hoops is an anxious, self-conscious work. Like Spiegelman’s Maus—and a great many other graphic memoirs since—it reveals and worries over its own stratagems. The authorial notes in the book’s back matter frankly discuss Yang’s sourcing and his occasional resort to artistic license. Said notes relate to the main story dialectically and at times critically (reminding me of the disarming notes in several books by Chester Brown). In particular, Yang admits that he has cast his wife Theresa as, essentially, his sounding board and proverbial better half: wise and practical, humorously tolerant of his anxieties, and full of advice and encouragement (or reasonable doubts about his judgment, as the occasion demands). Talking to Theresa becomes a means of registering Gene’s doubts about his own project, and the sometimes choppy ethical waters that the project gets him into. Though Theresa makes an impression, she does not really emerge as a full-blown character (and the same could be said of Theresa and Gene’s children). Yang notes that he took “particular liberty” with her dialogue: “I figured I could because, y’know, we’re married.” His notes are full of revealing asides like these, which invite a closer look at Dragon Hoops as a performance and a made thing, not just an artless recording of real-life events. Yang’s self-reflexive disclosure of his artistic feints happens not only in the back matter but also in the main story. Dig these two successive panels, on either side of a page turn: In particular, Yang depicts himself worrying over a single compromising plot point: a deeply troubling element of real life that threatens his desired “feel-good” story but that he feels he cannot omit. That ethical sore point is seeded about a third of the way into the book, after which Gene frets and frets over it—until a moment about four-fifths in, when Gene, or rather the book, enacts its moment of decision: Readers of Maus may be reminded of Art’s insistence that “reality is too complex for comics"—which Yang echoes here, stating that comics are “essentially lies.” (Spiegelman too sometimes casts his wife, Françoise Mouly, as a sounding board whose dialogue makes his work’s ethical complications clearer.) In the case of Dragon Hoops, this sort of self-reflexive gambit becomes a fundamental plot element, in fact a suspense generator, long before Yang reveals precisely why. We spend a good part of the book wondering what he is hiding, and how he will reveal it (of course, this plot tease makes it obvious that at some point he will). This isn’t a terribly original move—graphic memoirs have been depicting the rigors of their own making since at least Justin Green—but here it feels almost like a forced move, as if Yang was compelled to it by unnerving real-world details that he could not wish away. Anxiety over this point fundamentally shapes the book’s narrative structure. Dragon Hoops, then, perhaps seeks to inoculate itself against criticism. That is, Yang’s self-critical gambits (there are many) may be meant to deflect charges that his expert storytelling massages the truth a bit too much. I’m not sure that such charges would be fair—but I confess I don’t think Dragon Hoops is Yang’s most convincing graphic novel. Whereas American Born Chinese and Boxers & Saints continue to hint at mixed feelings even as they aim for conclusiveness and wholeness, this book wants to feel emphatically resolved. Yang’s trademark ambivalence yields to a sort of boosterism. At times, Dragon Hoops seems to apply the “underdog” template of most sports stories rather uncritically; for example, the book registers some complicated thoughts about sports, coaching, and Catholic education that its final pages don’t so much resolve as hush. Me, I would have liked to see more critical engagement of what it means to turn young athletes into media stars. I would have liked to see more of Coach Lou’s self-questioning. Dragon Hoops is smart and honest enough to acknowledge problems in the culture of sports, but still wants us to cheer at the final buzzer. Maybe it’s an ironic tribute to Yang’s storytelling that, in the end, I wasn’t quite there. In any case, the book’s reigning structural parallel—how the courage and tenacity of the Dragons empowers Yang to go “all in” himself, as an artist—feels a bit rigged alongside the terrible dilemmas depicted in his previous novels. But, man, it's hard to begrudge Yang the effort, because so much good stuff happens along the way. Dragon Hoops captures a culture, community, and season vividly, and is the very definition of what we should want from a major artist: a step in a new direction, and a dare-to-self that plays out in complex ways. No one could accuse Yang of making things easy on himself. And the book has taught me a lot. As my wife Mich and I take our daily break from isolation, walking the quiet neighborhoods around us, waving (distantly) at passers-by, we see a lot of basketball hoops on driveways and in yards. In fact, a couple of days ago, as we walked uphill through another neighborhood, we heard the sounds of shooting hoops before we came upon the sight: a quick dribble, a silence, a thudding backboard, then more of the same. Sure enough: someone was practicing basketball, solo, in a rear driveway, just barely visible above a tall gate. I had this book on my mind, and had to smile.

KinderComics, alas, has been away for too long. This spring and summer, I have had to channel my energies elsewhere. I hate to admit it, but my academic-year workload does not make room for frequent blogging, and when the summer or intersession comes around, well, then I end up having to advance or complete other long-simmering projects. Lately I’ve had to cut back, refocus, and make a point of not driving myself nuts! Still, I am going to push for several reviews this summer; I want to keep KinderComics alive. The field of children’s comics is too important, and my interest in it too intense, to let go. I’ll have a review of 5 Worlds: The Red Maze up later this week, and then a few (probably short) ones between now and Labor Day, in order to keep the engine humming. Thank you, readers, for checking out or revisiting KinderComics. I’ll keep pushing. There has been a great deal of news on the children's comics front during my four-month absence. Would that I could go into all these stories in detail:

Besides all that news, awards have been given out:

My gosh, what a busy and exciting field. Keeping up is a challenge! I hope to do a better job going forward. A sad postscriptWhen it comes to public-facing scholarship and comics criticism, one of the most inspiring figures to my mind was the late Derek Parker Royal, co-creator, producer, and editor of The Comics Alternative podcast. Derek, a major critic of Philip Roth, Jewish American literature and culture, and graphic narrative, passed away recently, leaving a grievous sense of loss in the hearts of many. He was a scholar, innovator, and facilitator of a rare kind, generous, engaged, and prolific, and will be greatly missed in the comics studies community. He brought many people into that community; for example, at the Comics Studies Society conference in Toronto last weekend, his longtime collaborator Andy Kunka spoke movingly of how Derek encouraged him to enter the field. I will think of Derek whenever I post here, and the soaring example that he set. RIP Derek. Thank you for your scholarship, your advocacy, and your spirit.Of course San Diego’s Comic-Con International begins today, along with the associated Comics Conference for Educators and Librarians at the San Diego Central Library. Part of me wishes I could be there, but, as the saying goes, I have other fish to fry. First, an announcement: After next Monday, July 23, KinderComics will be taking a four-week break so that I can prepare for the Fall 2018 semester and also address some technical problems that have arisen around this site. That is, I will have a review up next Monday, but after that KinderComics will likely hibernate until Monday, August 20. My hope is to get KinderComics on a more secure tech footing and then resume blogging on a biweekly basis just in time for the Fall semester. Expect this site to delve into teaching in a big way come August 20-27. I’m sorry that I’ll have to be out of action for a bit. KinderComics is something I’m very proud of, and has given new shape and meaning to my life as a comics reader. Since taking this blog public about four months ago, I’ve published nearly forty posts and reviewed nearly a score of books, including nine or ten brand-new titles. I’ve hosted posts by Joe Sutliff Sanders and Gwen Athene Tarbox, published news and commentary, brainstormed for my forthcoming children’s comics seminar, and drawn hundreds of visitors. This is a project I definitely plan on continuing, even if my teaching schedule may make weekly posting impossible. Essentially, KinderComics is my way of keeping track of the new “mainstream” in comics, practicing comics criticism, and reflecting on the emergent discourse of children’s comics scholars—so it matters a great deal to me. Look out for new posts on July 23 and August 20! Secondly, back on July 3, which to me feels like a hundred years ago, Inks editor (and my Comics Studies Society colleague) Jared Gardner published an interview with me at Extra Inks that delves into why I am doing KinderComics and what I hope this blog can contribute to the scholarly community. Jared, a top-notch scholar and critic, is one of my guiding lights in this profession, and I'm proud and grateful that he chose to spotlight KinderComics. In general, Extra Inks (the blog of Inks: The Journal of the Comics Studies Society) is a great resource for reviews and features pertaining to comics and comics scholarship, well worth bookmarking and visiting often. (Take for example my colleague Candida Rifkind's timely and helpful post spotlighting migrant and refugee comics, from July 8.) Thank you, Jared! Back soon...

This post is about teaching. As I said when I started KinderComics, one of my goals in doing this blog is to brainstorm publicly about a course I'll be teaching this coming Fall 2018 semester at CSU Northridge: an English Honors seminar titled Comics, Childhood, and Children's Comics (English 392). Despite having taught at the intersection of comics and children's culture for years (including bringing comics into my entry-level Children's Literature class and designing courses on picture books that also explore comics), this upcoming Honors seminar marks the first time I've actually pitched a course devoted to children's comics per se. I'm excited about the prospect, and honestly a bit daunted by it too. Why daunted? Comics and childhood, together, make for a sprawling, complex area—and perhaps you can tell from my course's title that I haven't yet committed to a particular focus. Which is to say that I haven't decided how to delimit the course or what objectives to put front and center. I've been thinking about those things for a while. Thing is, the students and I will have fifteen weeks together, which in practice, experience tells me, means about twelve weeks tops for introducing new readings. What's more, part of the brief for an Honors seminar with, say, between a dozen and twenty students is that the students take turns presenting to and teaching one another, sharing the results of deep, self-directed research (fitting challenges for an advanced course). So it seems clear that I'll have to make some severe choices when it comes to focusing down. Yow! I've thought of at least four potential foci that are important to me:

All these areas seem important. Child characters are central to the satirical and sentimental uses of comics and to the form's popular spread; the history of moral panic is crucial to understanding comics' reputation, even now; the depiction of childhood in adult texts is key to the burgeoning alternative comics and graphic memoir canon, from Binky Brown to My Favorite Thing Is Monsters; and the sheer popularity of graphic novels for young readers today is a trend so dramatic as to throw all the other areas into a new light. So, the question for me is, what objectives do I want students to achieve as they work at the crossroads of comics and childhood? With all this in mind, I'm inviting several of my close colleagues in children's comics studies to join me here in an intermittent series of posts that I'll call a Teaching Roundtable. This roundtable will amount to, again, brainstorming, and perhaps debating the importance of our different teaching objectives. First up, TOMORROW, will be Dr. Joe Sutliff Sanders, author of, among other things, the new book A Literature of Questions: Nonfiction for the Critical Child (U of Minnesota Press, 2018), editor of The Comics of Hergé: When the Lines are Not So Clear (UP of Mississippi, 2016), and faculty member at the Children's Literature Research Centre at the University of Cambridge. Joe will be following up on this initial post -- readers, please come back tomorrow to follow and chime in on the discussion! Add your voices! Thanks.

WELCOME to KinderComics, a blog at the intersection of comics studies, childhood studies, and children's publishing. Essentially, KinderComics will offer comics criticism and children's culture criticism. It will feature reviews and commentary centered on children's and young adult comics and picture books, children and young adults as readers, fans, and makers of comics, and depictions of childhood, adolescence, and coming of age in comics. Its content will consist mostly of brief reviews of recent graphic books, comic magazines, picture books, and other visual texts aimed at or depicting young people—but we will also include other things, such as longer essays, commentary, interviews, and link posts. This blog is mainly the work of comics scholar Charles Hatfield, or See Hatfield—that's me.* It's a sequel of sorts to a column of mine that never quite jelled at The Comics Journal between 2011 and 2013 (if you're curious, see reviews here, here, here, and here). At the heart of KinderComics is my enthusiasm for comics and picture books as art forms, and my critical interest in the ongoing reception, or cultural construction, of comics as a medium "for" children. You may notice that I'm somewhat skeptical about certain topics that come up often in discussions of children's comics, including reading levels, developmental theory, and formal educational uses of comics. I don't mean to reject these topics outright—they are important—but I do tend to view them critically. I will be glad to learn from readers when I make mistakes about, or too quickly dismiss, these topics (or any topics!). At bottom, I'm less concerned about work that is prescribed to children because it is supposed to be "good for them," more concerned with work that I think is actually good. Overall, I'm drawn to comics as a form of art and of text with its own traditions and aesthetics. I enjoy practicing the art of reviewing, and KinderComics is the place where I can share my thoughts about the part of my comics reading life that most directly concerns children and childhood. I hope I'll be able to post here once or twice monthly—and I plan to run a series of posts over the summer that will help me brainstorm and prep for my fall course "Comics, Childhood, and Children’s Comics." If you love comics and take children's texts seriously, I hope KinderComics will be right up your alley. Again, welcome! BTW, you can find (pretty much) this same introduction on our About page. *Charles Hatfield is Professor of English at California State University, Northridge, the author or co-editor of four books in Comics Studies, curator of Comic Book Apocalypse: The Graphic World of Jack Kirby (CSUN Art Galleries, 2015), and founding President of the Comics Studies Society. He has published essays on children's comics in the Children's Literature Association Quarterly, The Lion and the Unicorn, and ImageTexT and chapters in Keywords for Children's Literature (ed. Nel and Paul, NYU, 2011) and The Oxford Handbook of Children's Literature (ed. Mickenberg and Vallone, Oxford, 2011). He currently serves on the Children's Literature Association Book Award committee. |

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed