|

Man, I've been trying to catch up! What you see here is a short and personal list (though longer than the list I contributed to SOLRAD's Best) of new comics in print that kept me busy and happy, or productively on edge, in 2020 to early 2021. Most had 2020 publication dates, officially (I think). These twenty-five books or series are works I'll remember for a long time: books that felt urgent and/or mesmerizing to me and that fell into a bedside pile of "notable comics." I'm afraid these twenty-five do not include great webcomics, or short comics found outside of book or booklet form. Nor does it include certain books I might have admired had I been able to get to them. There is so much to catch up on, and so much more that I just can't include here, lest I make my head explode! Click on a book's cover to see a webpage with more info about the book. Note that many of these titles are not intended for children or young adults. PS. The two books that compelled me to redraw my mental map of comics this year were Dancing After TEN, by Vivian Chong and Georgia Webber, and The Sky Is Blue with a Single Cloud, a collection of comics by Kuniko Tsurita (1947-1985), masterfully curated and placed in context by Ryan Holmberg. Dancing After TEN, a collaborative memoir, overturns assumptions about the so-called autobiographical pact (as in, what exactly does the "auto" in autographics mean?), while also providing, with perhaps inevitable irony, powerful visual means of conveying one person's experience of what it meant to go blind. I think it's going to be a landmark among graphic memoirs depicting disabled experience. And the Tsurita volume, well, the surreal, elliptical, and haunting manga collected in it, the sheer beauty of the evolving artwork, the sometimes puzzling but always intriguing way it pulls me out of myself, and the superb contextualizing essay by Holmberg and Asakawa — it all adds up to an incredible gift: an important act of historical recovery as well as a bundle of great comics. BTW it's been an amazing year or so for scholar-translator-editor Holmberg, from The Man without Talent, The Swamp, and The Sky Is Blue with a Single Cloud, to his own personal scholarly/travelogue book, The Translator without Talent, to his reportage on antiracist comics activism in Graham, North Carolina. I first met Holmberg at (I think) the 2004 ICAF conference, and he's been expanding my understanding of comics ever since. Man, he deserves a medal. And I suppose Drawn & Quarterly, which has published translations of so many outstanding Japanese and Korean comics lately, is once again my Publisher of the Year. Thank goodness for them.

0 Comments

Class Act. By Jerry Craft. HarperAlley / Quill Tree Books, 2020. ISBN 978-0062885500, $US12.99. 256 pages. Billed as a “companion” to Jerry Craft’s Newbery-winning New Kid, Class Act is actually a direct sequel, following Jordan Banks and his schoolmates into the next year, but this time focusing less on Jordan and more on his friend Drew. The opening pages go to Jordan, and again his work as a budding cartoonist punctuates the story, in the form of comic strips notionally drawn by him—but Drew’s challenges, as a Black scholarship boy raised by a hard-working grandmother, soon take center stage. Drew’s pained awareness of class difference tests his friendships with Jordan and their affluent White schoolmate, Liam, and the plot tracks the awkward social negotiations among the three of them. Once again, Craft’s kids, brave and self-knowing, navigate the minefields of race and class, dogged by an inescapable sense of the things they don’t have in common; once again, their teachers are fumbling and oblivious. This time, Craft satirizes the inane efforts of their school, the tony Riverdale Academy, to extol “diversity”: teachers are dispatched to a conference called the National Organization of Cultural Liaisons Understanding Equality, and the school makes a failed effort to “adopt” a sister school whose working-class students of color don’t know what to make of Riverdale’s privileged, “bougie” atmosphere. As in New Kid, Craft observes all this in an amused, good-humored way, while never forgetting that difference can make all the difference. One tense scene depicts Jordan’s father being stopped by a White cop when driving in Liam’s posh neighborhood; moments like that affirm that Craft is playing for keeps, drawing out humor from real pain. Class Act, then, is smart and careful as well as high-spirited – though its story, I think, is more diffuse than that of New Kid, its stakes not quite as clear. (It would help to reread New Kid just before reading this one.) The book is busy and teems with in-jokes, including nods to comics and children’s book authors; sidelong gags are everywhere, to the point of distraction. More impressive is Craft’s diverse cast of distinctive, well-defined kids, many of whom get moments in the spotlight; they actually talk to each other, in courageous, meaningful ways, and Craft understands the subtle dynamics among them. You can tell he likes them. I confess that the art, with its jumbled, cut-and-paste style, clip-art elements, and CG backgrounds, put me off at first (I felt the same about New Kid). The work has an overbusy finish that mixes cartoony flatness with gradient coloring – an uneasy compromise. But Craft builds smart pages, and his socially engaged storytelling, once more, rings sharp, wise, and true. Dancing at the Pity Party: A Dead Mom Graphic Memoir. By Tyler Feder. Dial Books, 2020. ISBN 978-0525553021, $US18.99. 208 pages. Tyler Feder’s mother Rhonda Feder (née Hoffman) died of cancer when Tyler was nineteen, more than ten years ago. This memoir recounts Rhonda’s illness and death, her funeral, and the enduring sadness that has been part of Tyler’s life ever since—sometimes a still-raw, lacerating grief, sometimes a bittersweet nostalgia. That may sound just about unendurable: a self-pity party indeed. But what this book really does is pay homage to Rhonda Feder, evoke her particular, idiosyncratic self, and capture the way profound memories, very specific and odd memories that no one else could understand, arise unpredictably from quirky particulars and chance encounters. Yes, the book depicts, in fact enacts, grieving as a process, one that never quite ends, but it does so with verve, comic frankness, and surprisingly many laughs. In fact, at first, in the book’s opening pages, I wasn’t ready for Feder’s almost nonstop humorous flippancy, her many comic asides, satiric observations, and zingers. This sort of larking around in the shadow of death seemed like the very definition of Too Soon (although her mother died so long ago). To me, Feder’s approach at first felt too self-involved. But soon, very soon, the book crafts a precise portrait of Rhonda as a personality, lovingly remembered in all her quirks, the emotional, mental, and physical subtleties that made her who she was. Her eccentric liveliness, and that of her family, come through strongly, and Feder, in an unassuming and uncluttered style, balances deep sadness and irrepressible good humor, in a lovely, unforgettable tribute. Helpfully didactic at times (“Dos and Don’ts for dealing with a grieving person”), the book is mainly witty, personable, and compulsively readable—a remarkable example of how art, as Feder says, can “turn the crap into something sweet.” Little Lulu: The Fuzzythingus Poopi. By John Stanley, with Charles Hedinger, Irving Tripp, et al. Edited by Frank Young and Tom Devlin. Drawn & Quarterly, 2020. ISBN 978-1770463660, $US29.95. 276 pages. Lovingly edited, gorgeously designed, this second volume in Drawn & Quarterly’ deluxe hardcover Little Lulu series reprints more than thirty stories and strips, and a score of beautiful covers, that ran in the Dell comic book series circa 1949-1950. Written and laid out by John Stanley, these brilliant, economical, tightly wound comics were among the best of their time. They hold up well. Much has been said about Lulu as a feisty feminist icon who gets the drop on the sexist, obtuse, often mean-spirited boys in her neighborhood, and that’s true (the book’s introduction by Eileen Myles underscores that point); I was also struck, though, by the notes of human vulnerability and doubt in her characterization, by the signs of frailty and uncertainty that Stanley’s heroes often show. Lulu can be bullied, and Lulu can be hurt, but that makes her victories all the sweeter—she has real character. Stanley packs a surprising amount of human complexity into these condensed fables and gags. The tales are often absurd, sometimes satirical (such as “The Old Master,” a takedown of the art world), and always exquisitely timed, with gags and payoffs that depend upon very precise rigging. D&Q’s Lulu series is one of the best things happening in comics right now, even though the comics themselves are old. Drawn & Quarterly provided a review copy of this book.

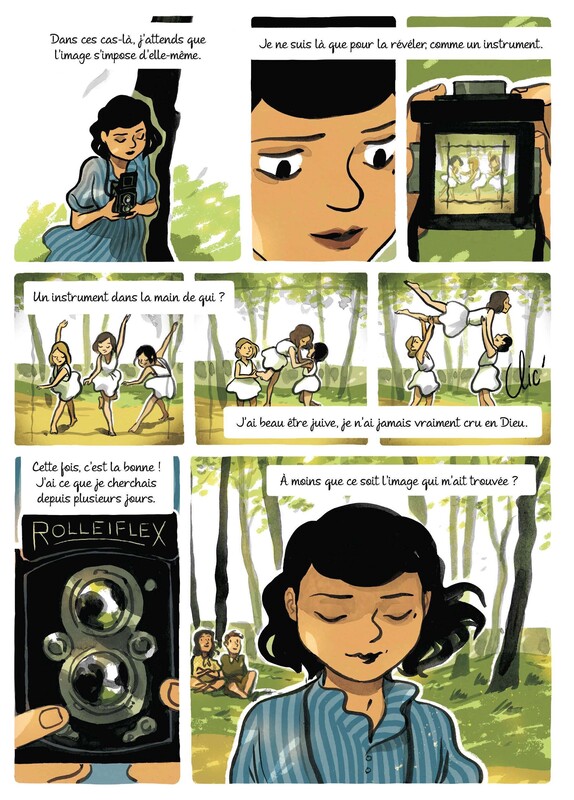

Catherine’s War. By Julia Billet and Claire Fauvel. Translated from the French by Ivanka Hahnenberger. HarperAlley, 2020. ISBN 978-0062915597, $US12.99. 176 pages. Catherine’s War is a finely shaded, beautifully cartooned, and engrossing book that ends much too abruptly. A historical novel stenciled from real events, it has been translated from the Angoulême Youth Prize-winning BD album La guerre de Catherine (Rue de Sèvres, 2017), which adapts Julia Billet’s prose novel of the same name (2012). Billet’s novel itself freely adapts, or at least draws inspiration from, the wartime story of Billet’s mother, Tamo Cohen, one of thousands of hidden children uprooted by the Holocaust: Jewish children sheltered from the Nazis, often in Catholic convents or among Gentile families. In real life, Tamo Cohen did attend the Sèvres Children’s Home (in fact a progressive, student-centered school), as does the protagonist of this novel, Rachel Cohen, and she did flee the Nazis, and she was renamed to pass as a Gentile, just as Rachel here is renamed “Catherine Colin.” But, as Billet admits in her notes, the story of Catherine’s War “remains a story”—a historical fiction interwoven with truths. Billet imagines Rachel/Catherine as a young photographer whose images of WWII are successfully exhibited in a Parisian art gallery soon after the war (an exhibition that replays many experiences depicted earlier in the book). Further, Rachel’s narration, implicitly, comes from her journal—so, she is an artist in words as well as pictures. In that sense, Catherine’s War becomes a Künstlerroman as well as a wartime tale of life on the run. Thematically, it reminds me of books like Whitney Otto’s ensemble novel Eight Girls Taking Pictures (2012), a fictionalized biography of eight women photographers, and comics like Isabel Quintero and Zeke Peña’s Photographic (2017), a YA biography of famed Mexican photographer Graciela Iturbide. Reframing Tamo Cohen’s story within the history of photography, Billet casts her mother, or rather Rachel, as a visual witness to the terrors of war. Armed with a Rolleiflex (like Robert Capa – or Annemarie Schwarzenbach?), the fugitive Rachel/Catherine becomes a chronicler as well as autonomous artist, even as she rushes from one shelter to the next to evade the Nazis. For all that, Catherine’s War is not explicitly violent. Though fear is ever-present, intimations of war and Holocaust are discreet; we never see the dreaded roundups or camps, or combat (though overheard dialogue among Resistance fighters does imply sabotage). The point of view is limited to what a child in hiding, pretending to live out her normal life, might have witnessed. Trauma is suggested by the extent to which Rachel and other young people help each other cope with it. The various children depicted (the story begins at the Sèvres home, and Rachel most often travels with other kids) are wounded by the shocks and partings they have to endure, yet they are resourceful, brave, and unselfish—not to the point of absurd angelic idealization, thank goodness, but in a tense, believable way. (Billet’s trust in young people mirrors the radical teaching philosophy of the Sèvres school.) Multiple scenes depict the challenge of trying to keep cover stories straight, the distrust stoked by constant surveillance, and the dread of giving the game away. Yet the novel is so discreet that it takes Billet’s endnotes to flesh out the terrible context of WWII. Those notes clearly anticipate a young audience, and I note that the book is blurbed by a notable writer of children’s nonfiction, Susan Campbell Bartoletti, whose work (Hitler Youth, Kids on Strike!, etc.) often extols young people’s activism and recounts harrowing historical facts with candor but also due sensitivity. Decorous would describe this book’s approach: from the story’s quiet hinting, to Claire Fauvel’s rippling brush-inking, gentle watercolors, and borderless panels, to the prim digital lettering (by David DeWitt). A genteel aesthetic overlays everything, conferring delicacy despite the nightmarish world evoked. What makes all this work is Fauvel’s patience, empathy, and attention to detail: from the opening pages, she tracks Rachel and the other characters with exquisite care, and their feelings, both spoken and unspoken, register honestly. Fauvel’s visual storytelling, if understated, is fluid and confident, moving characters about gracefully and capturing unwritten nuances in most every scene. She really cares about these characters. In short, Catherine’s War is smartly laid out, superbly drawn, and piercing. (For insight into Fauvel's process, and the book's production, see Billet's VanCAF presentation from last spring: a slideshow and talk captured on video, subtitled in English.) Not everything in the book works. There are moments where the book seems determined to spell out, rather than suggest, its messages—passages that seemed forced. In particular, a postwar scene depicting the ritual shaming (head-shaving) of French women accused of Nazi collaboration seems underdone; it doesn’t explain what’s at stake, and Rachel’s rejection of the shaming mob doesn’t register (though Billet’s endnotes work hard to underscore the didactic point). Also, as the book accelerates toward its end, things happen rather too fast. Both a crucial relationship and the postwar arc of Rachel’s life are sketched in abruptly over the last couple of pages. (It turns out that there’s a sequel, published in French in 2020, so perhaps the ending was meant to be a springboard?) When I turned the final page, I felt as if I was still in midair. That said, the gnawing dissatisfaction I felt got me to reread the book, which sharpened my appreciation of Fauvel’s subtle artistry. As I say every so often, I’d be glad to read more.

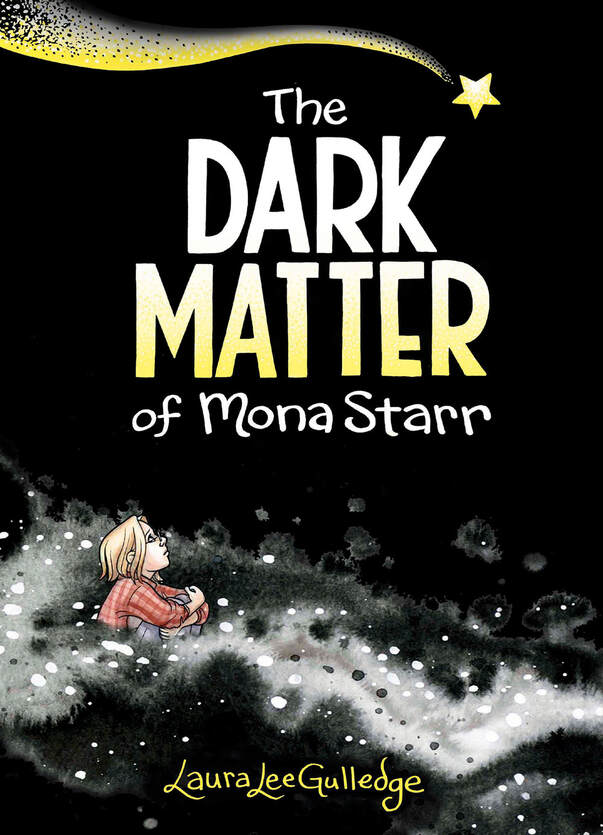

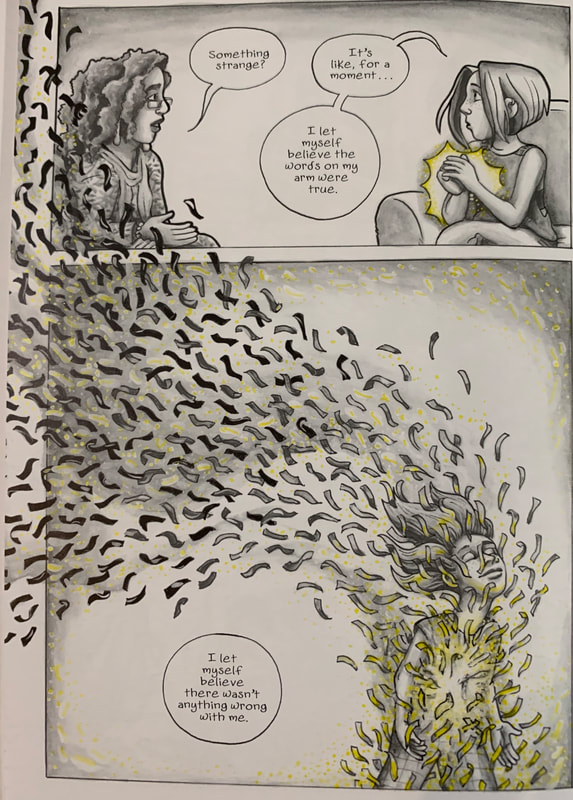

The Dark Matter of Mona Starr. By Laura Lee Gulledge. Amulet Books/ABRAMS, 2020. ISBN 978-1419742002, $US14.99. 192 pages. In this semi-autobiographical novel, Mona, a high-schooler and artist who suffers from depression, undertakes a self-study to better understand her needs and triggers and fashion a "self-care plan." Though a loner by temperament, she learns to think outside of herself and recognize loving relationships and creative collaboration as important resources in her life. With the help of her counselor, parents, and friends, Mona chooses an ethic of community and participation, sharing her aesthetic gifts and inspiring others to do the same. Looking beyond herself, even as she honors her own needs, enables her to engage the world on different terms and, to some degree, counteract her depression. The novel climaxes with a community art project in which Mona and her self-styled "Artners," Aishah and Hailey, invite many of their fellow high-schoolers to collaborate in a spirit of loving community. The story's keynotes are self-love, self-advocacy, and willful optimism, and its last word (literally) is hope. Like Ellen Forney's celebrated memoir Marbles, this novel hovers between raw personal storytelling and hortatory self-help, with chapter headers that give emphatic advice, such as Turn emotion into action and Break your cycles. Author Gulledge shares her own self-care plan in the back pages, and her notes confirm that Mona Starr is indeed based on her. Artistically, the book is wildly expressive; the pages brim with visual metaphors of depression and elation, self-isolation and self-release, artistic engagement and pure joy. Depression, Mona's so-called dark matter (her mom is an astrophysicist), appears as swirling black clouds, faceless anthropomorphic demons, dark waters, black flames, and gripping hands. Moments of self-realization and delight are accompanied by stars and streaks of bright yellow: the one spot color in Gulledge's otherwise black-and-white, or rather grayscale, aesthetic. Mental landscapes — vast oceans, deep, dark wells, and the swirling cosmos — convey Mona's ever-shifting inner state. Consensus "reality" is perfused with expressionistic symbolism, and many pages leave behind real-world settings altogether. The sheer profusion of visual symbols reminds me of, say, Iasmin Omar Ata's Mis(h)adra (a semi-autobiographical account of epilepsy that is likewise braided with graphic devices signaling the protagonist's inner state). Gulledge's figures, word balloons, and symbols routinely break out of her panel grid — in fact, there is not one page that obeys a strict, unbroken paneling — and the layouts are ceaselessly dynamic. Immersive full bleeds are frequent. In short, the book is a staggering exercise in expressive drawing and page-making. Story-wise, though, Mona Starr feels a bit thin and undeveloped to me. Despite hints that other characters may also struggle with mental illness or disability, and despite the plot's emphasis on seeking "help" and community, the novel feels very much absorbed by Mona's mental state and Gulledge's exhortations to embrace one's creativity. The book feels idealized, dreamy, and self-involved; Gulledge's artistic bravura, the sheer busyness of her pages, doesn't let the depression seem real. Everything is couched in terms of artistic therapy, self-study, and a self-improvement "project." Mona's counselor is introduced at the start, before Mona's depression has manifested narratively, and the greater context is emphatically reassuring. Much of the book consists of poetic self-reflection, heightened by the overflow of visual metaphor, as if in confirmation of Mona's creative "genius" (a personality test labels her "the potentially unstable visionary type"). Familial and social complexity take second place to exploring Mona's state of mind through ravishing visuals. The singular focus on Mona's feelings and self-conception would probably be smothering in bare prose; only Gulledge's ecstatic imagery gives the story life and depth. The result is heady and interesting but, I'm tempted to say, less novelistic than an exercise in didactic self-help. Somehow, the book manages to be at once lyrical, spectacular, and a confidently crafted exercise in comics, yet also frustratingly under-done, as if Gulledge couldn't quite take distance from what is, after all, a kind of exhortative autofiction. But here's the deal: I enjoyed reading Mona Starr, and it has moments that, on re-reading, still get me choked up. The book's conclusion is calming and gratifying, and I cannot deny Gulledge's hard-won insight. I am pretty sure that some readers will be affirmed, and perhaps even forever changed, by reading this book. I wouldn't recommend Mona Starr for complex, intersubjective storytelling, but will remember its powerful evocations of feelings and states of mind, as well as Gulledge's confident artistry.

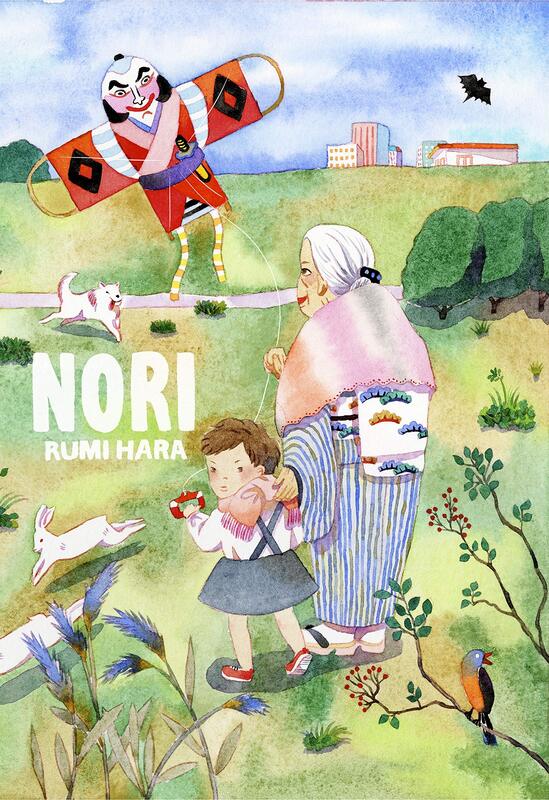

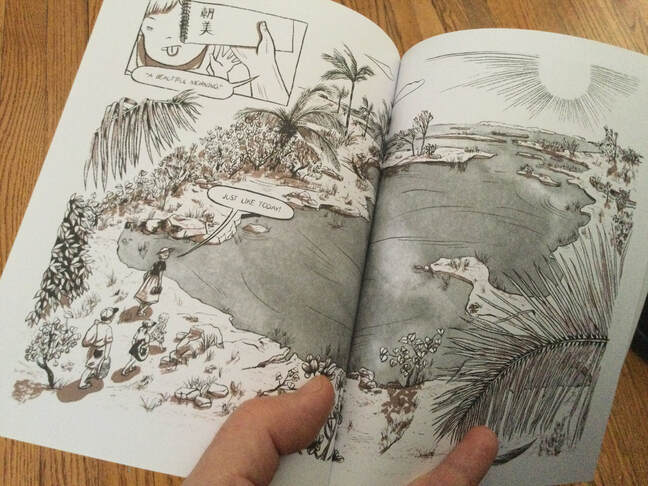

Nori. By Rumi Hara. Drawn & Quarterly, 2020. ISBN 978-1770463974, $US24.95. 228 pages. Collecting a series of minicomics begun in 2016. I regret not reading Nori sooner. It’s great: a poetic, beautifully observed portrait of one Japanese girl’s (and her grandmother’s) life, unforced, elliptical, and deeply personal. Sadly, this sort of evocative and searching book often gets dismissed by proponents of children’s books as too confusing or difficult (I know—I’ve been in quite a few conversations like that). Rumi Hara’s tale, seemingly semi-autobiographical, recalls a mid-1980s Japanese girlhood of a particular kind, in a scruffy, organic style that, for me, calls to mind Debbie Drechsler, early Lynda Barry, or Henrik Drescher. There's a similar fascination with texturing, in this case achieved through a versatile dry-brush technique that lends mood and specificity to each scene (Hara reportedly works on handmade paper, and her surfaces have a kind of nap, or nubbliness, a delicious roughness). Graceful use of a different spot color in every chapter imparts added flavor and also an overall sense of structure. I found Hara’s pages a bit disorienting at first—so rich are they—but man are they beautiful, and transporting. There are enchanting spreads here that just carry me away. Noriko, or Nori, an energetic girl of about four or five, is never disciplined out of her own free self, and remains, throughout, stubborn and even volatile, at times perhaps a bit of a pill, but really a delight. Her spirits are never sacrificed for some insufferable didactic point about maturing or becoming less of a challenge to grownups. Thank goodness. Nor does she just stand in for “childhood” as a vague state of freewheeling, unworldly innocence. She and her world are too particular for that—again, thank goodness. I grew to love this specific girl and her patient, but not over-idealized, granny, who in effect mothers Nori while the girl’s parents are busy working, working. This is a soulful book, empathetic and unpredictable, without obvious designs on the reader. Hara's storytelling takes an outside observer’s view most of the time, not giving us too-easy access into Nori’s (or anyone’s) thoughts, and sort of ambling from one thing to another, or so it seems, without obvious crises or problems to solve. But then bursts of dreamlike fantasy, brief and powerful, intervene, showing Nori's thoughts as she communes with her environment or works out her own fantastical logic. At those moments, Hara takes us in deep, but without ever showing her hand. We get glimpses of a magical but not overly sweet inner life; there's a touch of the uncanny as well (Hara says, "I like stories that have a little creepiness to them, like old folk stories that are simple but mysterious"). And as it turns out, the stories, which at first seem to have a shaggy-dog waywardness about them, are insinuating, carefully crafted, smartly rounded and complete, with levels and levels of implication and (if you care to reread and ponder) symbolism. Seeming threats turn into affirmations; the uncanny becomes lovable, yet never saccharine. I particularly enjoyed the long, ambitious story in which Nori and granny unexpectedly win a trip to Hawaii and have a wonderful, though complicated, visit there. Writing and art are both electrifyingly good here. I didn't get to read this, one of the best books of 2020, until a week into 2021. For shame! Most highly recommended. Drawn & Quarterly provided a review copy of this book.

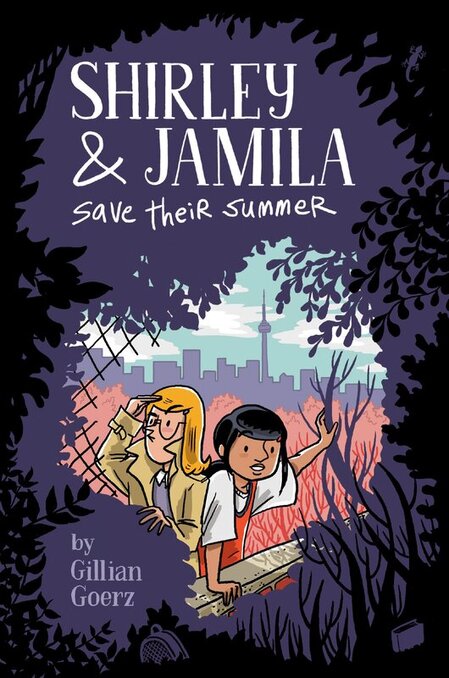

First, a brief personal note:You might think that being in pandemic lockdown would mean reading lots of comics, and with relish. I had thought so too. But I have to confess to feeling adrift lately; if anything, I may have been reading fewer comics than usual. I frankly don’t understand this, and it makes me sad, but there it is. COVID seems to have wrought havoc with my reading life, and many of the talked-about comics of 2020 are still unknown to me. Usually, I look back on the year in comics with a surplus of terrific new titles that I have trouble choosing among. Bounty is my normal. This year, though, I've had a hard time envisioning a Best-Of list for KinderComics. I've been down in the dumps about this for a bit. That's why it is such a pleasure to have contributed, in however small a way, to SOLRAD's list of The Best Comics of 2020. This multi-authored listicle is an education to me: a reminder of how widespread, diverse, and unpredictable comics can be. SOLRAD, "a nonprofit online literary magazine dedicated to the comics arts," has just celebrated its first anniversary, and it's a great site, an essential stop for readers who care about innovation and artistry in comics. I'm glad to have done anything for them, and very glad to have their Best-Of list as an antidote to my blues. Please go check it out! And now, back to what KinderComics usually does: Shirley and Jamila Save Their Summer. By Gillian Goerz. Dial Books, 2020. ISBN 978-0525552864, US$10.99. 224 pages. I like this sunny middle-grade mystery, which follows a pair of mismatched but true friends who investigate a theft at a local swimming pool. It’s the sort of thing that could hit the spot for fans of Nancy Drew, Encyclopedia Brown, or Nate the Great. The setting appears to be suburban Toronto. Shirley is a super-observant Holmesian kid detective, also a social outcast: a tightly wound nerd-savant figure, perhaps implicitly an Aspie (the characterization seems to lean in that direction). Jamila, the novel’s true focal character, is an aspiring athlete, eager and restless, loved by her family yet perhaps overshadowed by her older brothers. Jamila and Shirley, temperamental opposites, need each other; both girls chafe against the protectiveness of their moms and are looking for ways to buy a bit of freedom over the summer. They team up to break out. Shirley is White, while Jamila comes from a South Asian, perhaps Afghan or Pakistani, ostensibly Muslim family; the girls' neighborhood is convincingly diverse. We learn much about Jamila’s family, the dynamics of which are deftly established, with discreet cultural cueing and an easy, lived-in complexity. (I particularly liked the characterization of her mother, a subtle and telling depiction.) Despite some early signs of tentativeness (say, in layout and balloon placement), Goerz crafts a tightly constructed, unflagging, engaging story, one that hopscotches confidently from chapter to chapter, evokes a credible social milieu, and, best of all, vividly imagines what turns out to be a large repertory company of characters. This is, in the end, a sure-handed, well-edited, handsomely cartooned first graphic novel for Goerz: in sum, a cool book. It looks to be the first volume in a projected series; I'd happily read more.

This week's Modern Language Association (MLA) convention, to be held online January 7-11, will, as usual, feature panels and papers related to comics studies and to children's literature and culture studies. It's a giant conference, with comics and children's culture scholars making up only a small (though vital!) part of the proceedings. I'll miss attending it in person this year, as Mich and I did last year in Seattle, but it's good to see that the MLA has arranged a big, ambitious virtual alternative! On New Year's Day, my colleague Phil Nel posted his annual blog entry listing all of this year's MLA programming related to comics, children's texts, and childhood studies. The list is a great resource, a kind of navigational aid to accompany the MLA's enormous program; check it out: https://philnel.com/2021/01/01/mla2021/ There's a wealth of very promising work on offer this year. So many names leap out at me (such as Brigitte Fielder, Margaret Galvan, Rachel Kunert-Graf, Rachel Miller, Anna Peppard, Alex Ponomareff, Jan Susina, Gwen Athene Tarbox, Erin Williams, and Daniel Worden), and I'm sure there will be informative and inspiring work by many scholars whose work I haven't gotten to know yet! I'm particularly excited about Comics and Graphic Narratives for Young Audiences, a special panel on Saturday, Jan. 9, co-sponsored by the Forum on Comics and Graphic Narratives and the Forum on Children's and Young Adult Literature, to be chaired by Phil and our colleague, Aaron Kashtan. It's always exciting to see those two communities working together! As I said in my previous post, these are exciting times in comics studies! PS. Thanks, as ever, to Phil Nel for the info and inspiration!

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed