|

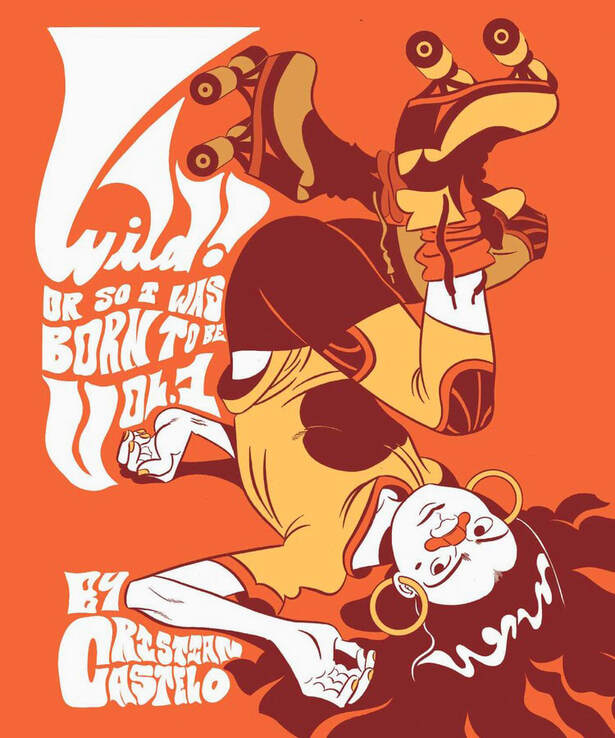

Wild! Or So I Was Born to Be, Vol. 1. By Cristian Castelo. Oni Press, ISBN 978-1637150931, 2022. US$29.99. 208 pages, oversized softcover. Wild is a delightful yet frustrating comic. Delightful because artist Cristian Castelo cartoons the hell out of it, with an energetic, superflat, ultrabright style. The pages sing. The story's 1970s roller derby milieu and fearsome all-girl cast (reminding me a bit of Jaime Hernandez's wonderful luchadores) grant him license to do colorful, braggadocious roller rink action and cartoon violence. It's a gas, full of fierce posing, trash talk, and big, mythic characters. The sizzling red/orange/gold palette, outsized format, and inventive layouts practically gave me a contact high! So, yeah, I enjoy rereading and poring over this comic. OTOH, Wild is confusing as hell. Beyond protagonist Wild Rodriguez and a couple of hard-bitten, superheroic roller divas, the cast is indistinct. Supporting characters blur into each other, and everybody lurches off-model. In fact, some characters don't seem to have a consistent model (in one scene, a very minor bit player ends up looking like four different people). The settings lack a 3D sense of habitable space, and action does not flow logically from panel to panel. Locales are gestural at best, and the high-throttle action scenes don't actually communicate anything about roller derby as a game. There is snarling and there is hitting, but what else is the sport about? The plot lunges here, then there; eccentric narrative doglegs turn out to be crucial (the accumulated effects of serialization are all too easy to see). Cross-cutting between different locales and different bouts makes the book's home stretch dizzying, and not in a good way. Castelo's elastic cartooning works somewhat against narrative coherence. His style has shifted a lot since this project began. In 2019, I bought one of the riso-printed, handbound collections of the unfinished Wild (then a work in progress) at comicartsla.com, and I can see remnants of that draft here, in panels that are not quite as crisp as the rest of the book. The newer style is razor-sharp and fairly staggering. At times, Castelo seems to have worked over (and around) the older stuff, punching it up, adding new connections, rethinking and complicating the story — but the end results don't add up narratively. Problems in simple legibility are made the worse by Castelo's expressionistic, ever-shifting use of his limited color palette; the characters' costumes are not taggable by color, because a yellow outfit in one panel becomes a red outfit in another. That may sound like a petty complaint, but it becomes a problem due to the sheer density of the pages, indistinctness of minor characters, and ill-advised cross-cutting between scenes. The book is just plain hard to follow. But man, what cool things are hiding in here: Wild Rodriguez's mixed family and ambivalent ethnic identity; the roller divas' complicated, nuanced backstories; the way the major characters bear the weight of cultural politics; the sheer unabashed ass-kicking comic fury of the story. One aspect that makes the reading even harder — the difficulty of parsing "dream" from "reality" — strongly appealed to me. So did the overwhelming style. I'm glad to see such a vaulting, ambitious, and, yes, wild comic touted as a YA book. Castelo may yet deliver a great all-around comic. I bet he will. In any case, I'll happily queue up for the next volume of Wild. My complaints notwithstanding, Volume One is a gorgeous, headstrong, gutsy experiment. I think it fails narratively, but it fails in such a way that I long to see what Castelo does next.

0 Comments

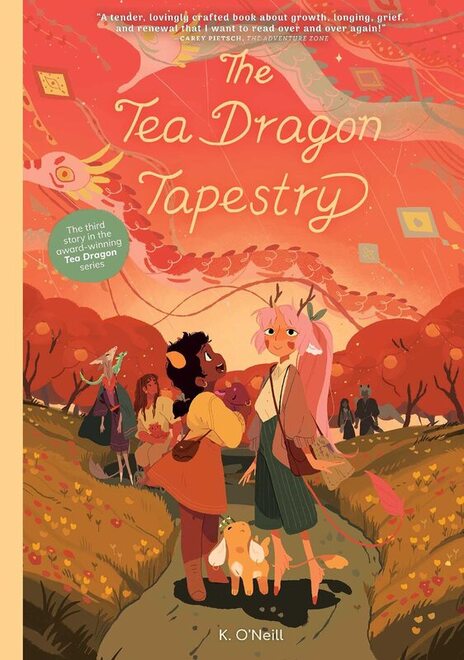

The Tea Dragon Tapestry. By K. (Kay) O’Neill. Oni Press, ISBN 978-1620107744 (hardcover), 2021. US$21.99. 128 pages. For weeks, my family and I have been playing the Tea Dragon Society game Autumn Harvest, based on Kay O’Neill’s comics series (the first two books of which I’ve reviewed here, and here). I’ve won a few games and lost many. I enjoy the game; it’s happy and challenging and graced with beautiful graphics by O’Neill. The gameplay feels very much in tune with the ethos of the comics. In all this time, til now, I have not thought to read the third and final volume of the comics, The Tea Dragon Tapestry. I don’t know why. Maybe I just wasn’t ready for another dose of O’Neill’s gentle and affirming storytelling, another spell in the tea dragons’ idyllic fantasy world. The past year has been bruising, and I am tired. Or maybe I feared reading through it and having to leave it behind, too quickly. I’m glad to have read it, now. Tapestry is the most mournful, but then the most joyous, of the three books—the one that feels most like a healing for genuine hurt. As usual, the challenges and conflicts are conveyed with a tender, whispering lightness; O’Neill doesn’t push too hard. As usual, the mood is that of a communitarian, vaguely anticapitalistic pastoral: a utopia of cute and mystic creatures, some humanoid, some not, living, giving, and crafting in a spirit of contemplative harmony. You know, I really am sad to have to leave this world behind—fortunately, a book can always be reopened. O’Neill’s tea dragons (in fact, small, catlike creatures whose bodies grow tea leaves) live symbiotically with people in an unforced arrangement that exemplifies commensalism and loving attachment. O’Neill’s humans (in fact, a range of anthropomorphic characters, such as fauns and centaurs) serve as caregivers to the dragons, as well as crafters, each devoted to a specific discipline that benefits their village community and the larger world. Scenes of brewing and drinking tea punctuate the stories, evoking an unhurried life defined by discreet rituals and communal care. In Tapestry, one of the tea dragons, Ginseng, mourns the loss of her previous caregiver, while Ginseng’s current caregiver, Greta, struggles to figure out how to help her. Meanwhile, Greta’s friend Minette, uprooted from what she thought her life was going to be, mourns the life she used to have while trying to commit to and find joy in the way she lives now. At the same time, Kleitos, a peripatetic blacksmith, considers taking Greta on as an apprentice (again the emphasis on crafting) but mourns the fact that he has lost the joy that smithing once brought him. O’Neill’s major characters all suffer from dislocation or loss, and each is quietly bereft in their own way, but they cope with these feelings in the context of a loving, sustaining community. As ever, O’Neill’s storytelling is empathetic, understated, and rooted in everyday routines rather than bombastic and action-filled. And, as ever, the drawing is gorgeous: O’Neill renders their characters and settings without containing contour lines, as blocks of color. The colors are solid, not painterly, but often mixed with such subtlety that it helps to read the book under a bright light. O’Neill’s cartooning is sweet and elegant rather than rowdy or assertive, dedicated to form rather than line. The net effect is like that of a Miyazaki-esque ecofantasy art-directed by Mary Blair. Works for me—I have to admit, I love looking at these pages. When I reviewed the previous books in the series, I was rather too grumpy, complaining that their subdued, gentle approach made genuine high-stakes conflict impossible—that the books were too Edenic, too idealized, and unwilling to deal with the tough stuff. I recant those remarks! The conflicts are there; you just have to lean in close and look and listen carefully. The gentleness is intentional, but there is a critical intelligence at work too; the world conjured in these books offers ways to envision a better world of our own. The Tea Dragon series is a remarkable thing. I gather O’Neill has finished with the series, and I can only say, damn, that’s a shame—I’d love to spend more time in this bucolic yet urgently humane story-world. The game helps.

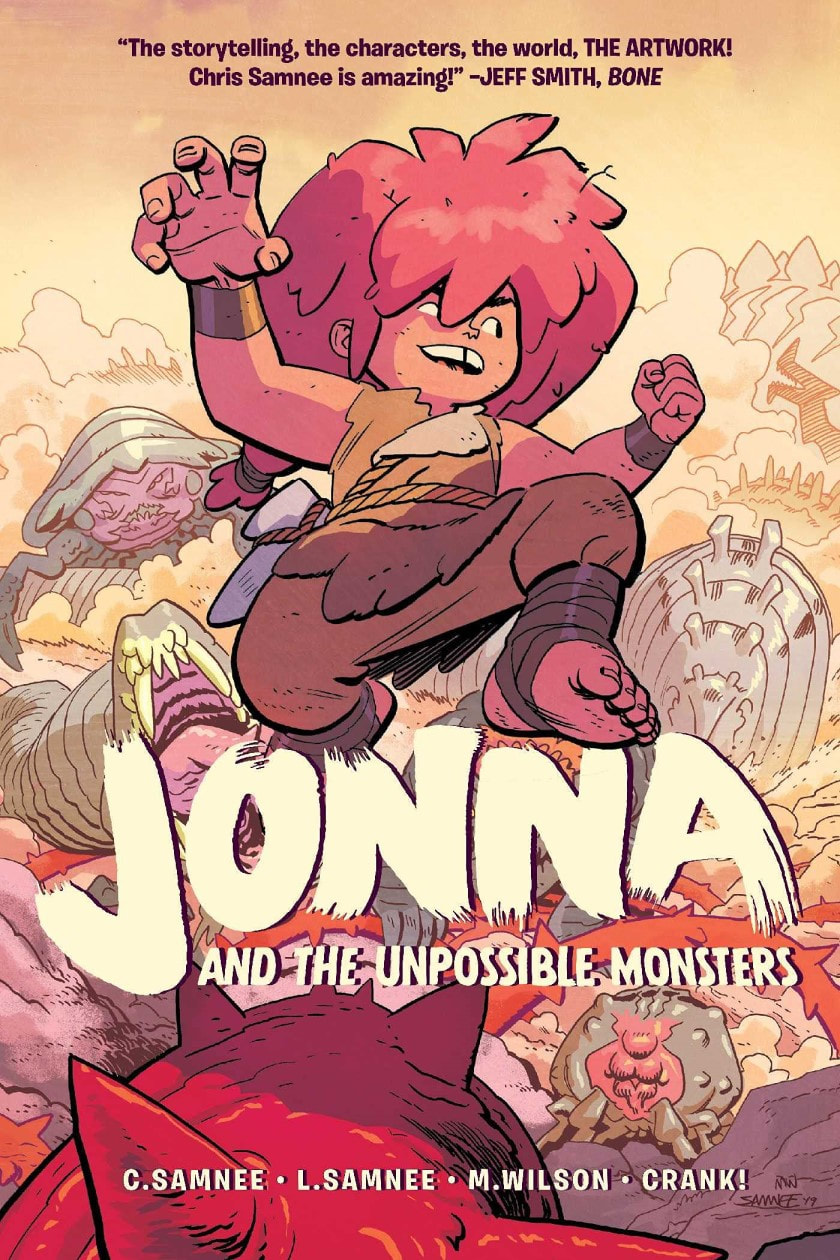

Jonna and the Unpossible Monsters. Book One. Written by Chris Samnee and Laura Samnee. Drawn by Chris Samnee. Colors by Matthew Wilson. Lettering by Crank! (Christopher Crank). Oni Press, August 2021. ISBN 978-1620107843, $US12.99. 112 pages. Jonna and the Unpossible Monsters has a premise that was just waiting to happen, one that somebody, somehow, had to get around to: a postapocalyptic children's fantasy about fighting giant, kaiju-like monsters. There's a touch of Jack Kirby's Kamandi, the Last Boy on Earth about this, and maybe a touch of Pacific Rim too. Co-creators Laura Samnee and Chris Samnee describe Jonna as a story they "could share with [their] three daughters," something created "for them" but also "inspired by them"; the comic, though, will appeal to action-starved fans of Chris Samnee's work on such superhero comics as Thor the Mighty Avenger, Daredevil, Black Widow and Captain America (or his current martial arts fantasy with writer Robert Kirkman, Fire Power). The heroic Jonna is a wild, monster-clobbering girl with a whiff of Ben Grimm or Hellboy. She comes across as untrammeled, almost feral, yet delightful. When Jonna goes missing in a ruined, kaiju-ravaged world, her older sister Rainbow – the more fretful, responsible one, naturally – tries to find her, then corral and (re)civilize her. Jonna, though, remains a unpredictable force of nature. You don't need to know much more; the first half dozen pages give you whopping big monsters, and plenty of synthetic worldbuilding. There's a sense of the familiar about all of it, but novelty and excitement too. By now it's almost a cliché to speak of Chris Samnee's masterful storytelling and sheer chops (I've paid tribute before). It is true that I will read just about anything drawn by him, especially when it's colored by Matt Wilson, his steady collaborator for more than a decade. Granted, I got impatient with Fire Power within a few issues. Though I dug its bang-up start, Fire Power strikes me as a shopworn White martial arts fantasy à la Iron Fist; it's tropey, and conceptually a bit tired. I've stayed with it, however, because of Samnee and Wilson's visuals, and it has become my monthly dose of old-school craft and loveliness, balancing breathless action with an Alex Toth-like elegance. Samnee manages to be polished and rugged at once; his drawing offers classicism and grace, but with a terrific infusion of energy. Jonna, I think, may be the best thing he has ever done: the pages sing, and roar, and astonish with their gusty action and playfulness. Freed somewhat from the stylized naturalism of mainstream superhero comics (though that skill set is still very much in evidence), Jonna cartoons with a joyful freedom. Wilson's coloring, too, is eye-wateringly good. All this is my way of saying that Jonna is craftalicious and affords plenty of gazing and rereading pleasure after the initial readerly sprint. But what does it amount to? On some level, it remains a kind of superhero comic, not only because Jonna packs a mean punch but also because a couple of other characters discovered along the way, Nomi and Gor, are seasoned fighters as well (Nomi boasts powerful prosthetic arms). So, this is a slugfest. But there's more: moments of poignancy, sisterly anxiety, and Jonna's weird, ferine energy and charming social cluelessness. And the Samnees allow a certain melancholy to creep in; the world of Jonna is a fallen one, full of sundered families, lost loved ones, bereavements. In one scene, a ragtag group of survivors huddles around a fire, and their dialogue says a lot: My whole family gone. My home destroyed. My village destroyed. Everything destroyed. Without pressing the point, the story has a genuinely apocalyptic feel that, to me, reeks of COVID. That it manages to be cockeyed and funny at the same time is no small feat. Though billed as a children's story, Jonna is just as much for grownups. The book (originally serialized in floppy form) splits the difference between direct market-oriented cliffhanger series and middle-grade graphic novel, so it's courting multiple audiences. Moreover, a theme of "families and belonging" (as the Samnees put it) threads through the book, familiar from many an animated family film, and like such films Jonna offers adults a kind of reassurance even as it aims for kids. That is, it offers childhood as a cure for ruin and heartbreak. The basic ingredients are familiar – there's nothing revolutionary about this tale – but I'm at a time in my life where seeing kids wallop monster does me a world of good. This first volume (a second is promised for Spring 2022) sets up some mysteries, not least the mystery of Jonna herself, and doesn't answer very many questions, but I enjoy paging through it and rereading it. In fact, I enjoy it more than I can say. PS. The excellent magazine PanelxPanel, by Hass Otsmane-Elhaou and company, devoted a good chunk of its May 2021 issue (No. 46) to Jonna, and includes a revealing interview with Chris Samnee. Plus, the issue contains other articles on depictions of children and on young readers' graphic novels. Well worth checking out!

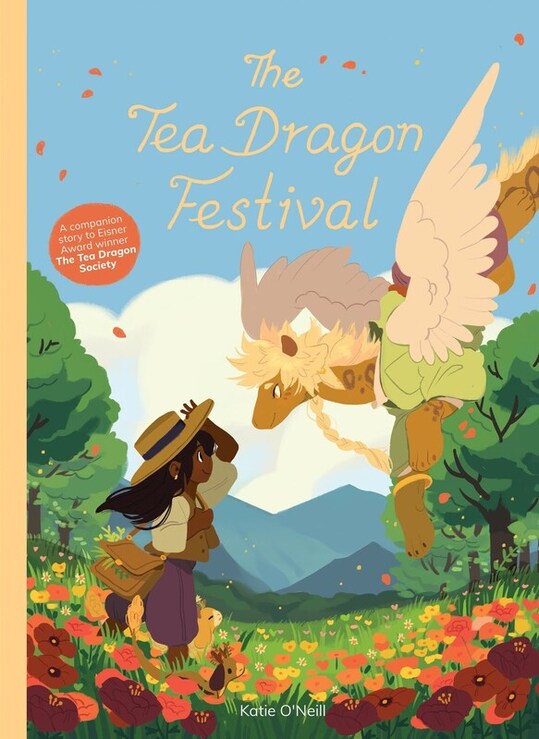

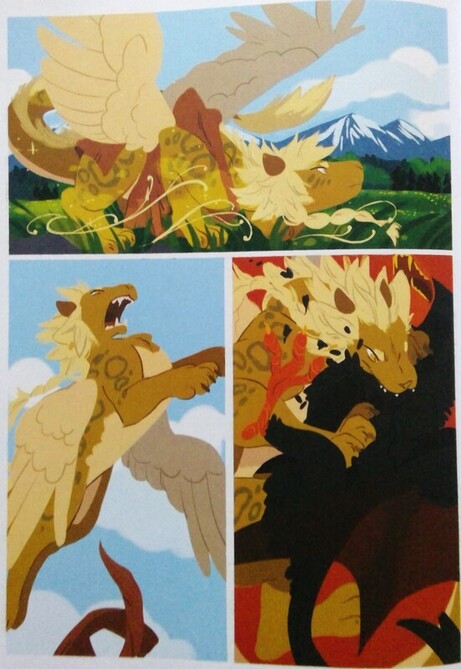

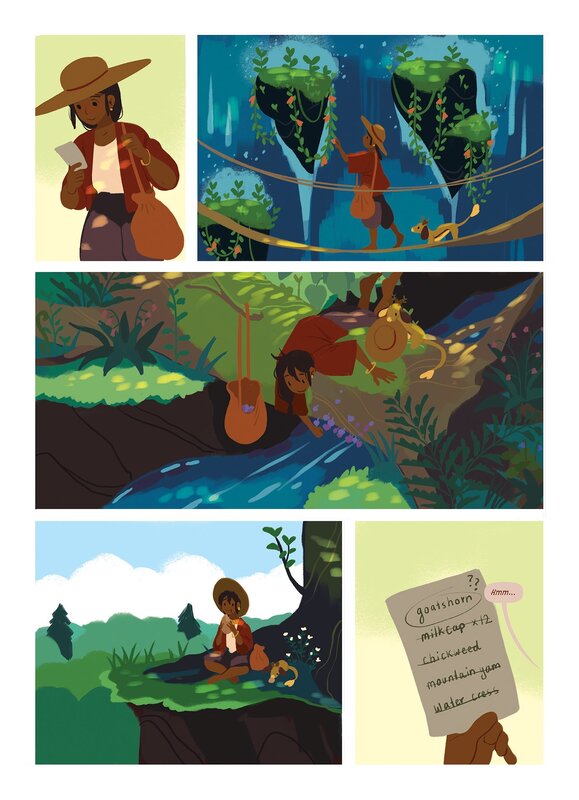

The Tea Dragon Festival. By Katie O’Neill. Oni Press, ISBN 978-1620106556 (hardcover), 2019. US$21.99. 136 pages. I read The Tea Dragon Festival during an early morning idyll, propped up in bed with a cat curled up on my lap (our cat Max likes to hang with us when we read). That sounds about right — it’s that kind of book: tranquil, comforting. A purring cat, basking in a morning ritual, is a pretty good stand-in for the semi-domesticated “tea dragons” that populate its world. In fact, here on KinderComics I described this book’s predecessor, The Tea Dragon Society (2017), as an “idyll full of greenness and life” and a “cat-lover’s daydream.” The same goes this time. The biggest problem I had with this sumptuous book was reading it by diffuse sunlight: O’Neill’s occasional layering of dark or muted colors posed a challenge to my eyes; I couldn’t make out certain expressions and overlapping shapes. I ended up having to turn on my reading lamp and point it directly at the pages — then the expressions popped. So, I recommend reading The Tea Dragon Festival by strong light; then you’ll really get to see O’Neill’s ravishing color work. When well-lit, the book fairly glows. Cover blurbs describe Festival as warm, charming, and gentle. Again, that sounds right. The story skirts pain and hardship; though it evokes some subtle melancholy, its characters are not burdened with difficult ethical decisions or hard losses. The vibe is green, dreamlike, and utopian (with the now-expected traces of Miyazaki). The one potential source of serious conflict appears and disappears in a handful of pages. In fact, the book is so quiet and anodyne that it’s quite a surprise when a fight briefly breaks out: Like its predecessor, Festival takes place in an eco-topia: an idealized rural culture defined by caring community and respect for traditional crafts. The story, again, focuses on a growing girl who is learning a craft — in this case, cooking — and her interactions with dragons — this time, not just miniature tea dragons but also a full-blown, shape-shifting, often humanoid dragon. This dragon, Aedhan, considers himself the appointed protector of the girl, Rinn’s, village, but has been waylaid by a magical, eighty-year sleep, from which he has only just awoken. He is filled with regret for the years he has missed. Rinn takes responsibility for helping Aedhan get to know her people and acculturate to village life — so, once again, the story revolves around the sharing of memories, as Aedhan moves from outsider to trusted villager. Though longer and more ambitious than the first book, then, Festival takes up the same concerns and exhibits the same qualities. I like O’Neill’s work for emphasizing, as I’ve said before, loving connection and tender gestures. But I have to repeat another observation too: this book’s delicacy left me wanting more complication, more trouble. I wanted a harder story, something that would show the characters’ values when put to a fiercer test. It’s easy to love the world O’Neill has created, one of sharing and openness, indeed a queer, feminist, anti-capitalist utopia. Clearly, she herself loves the world and its characters. I particularly like the inclusion of signing (American Sign Language) as a plot element, which sharpens O’Neill’s already impressive sense of (in this case literal) body language. The story, though, gives no sense that the apple cart has ever been upset, or the people’s equanimity challenged, by the ordinary work of survival. O’Neill seems to prefer quieter dilemmas, smaller stakes. Festival is sweet and affirming, but its plot evanesces soon after reading, leaving behind an impression of a personal wonderland, exquisitely tended and mostly about the pleasure of its own rendering. I’ll happily read more by O’Neill: she’s a gifted cartoonist and book artist. Each time I read her, though, I become terribly aware of my own cynicism. Harrumph!

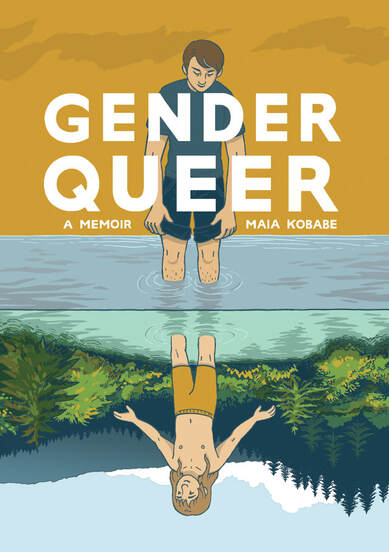

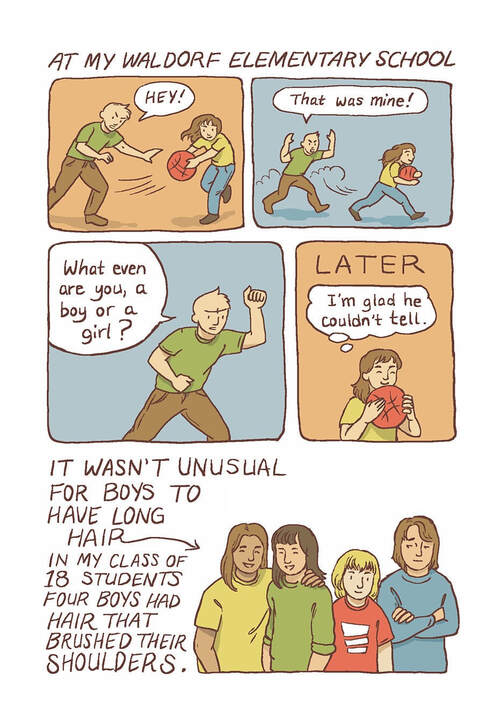

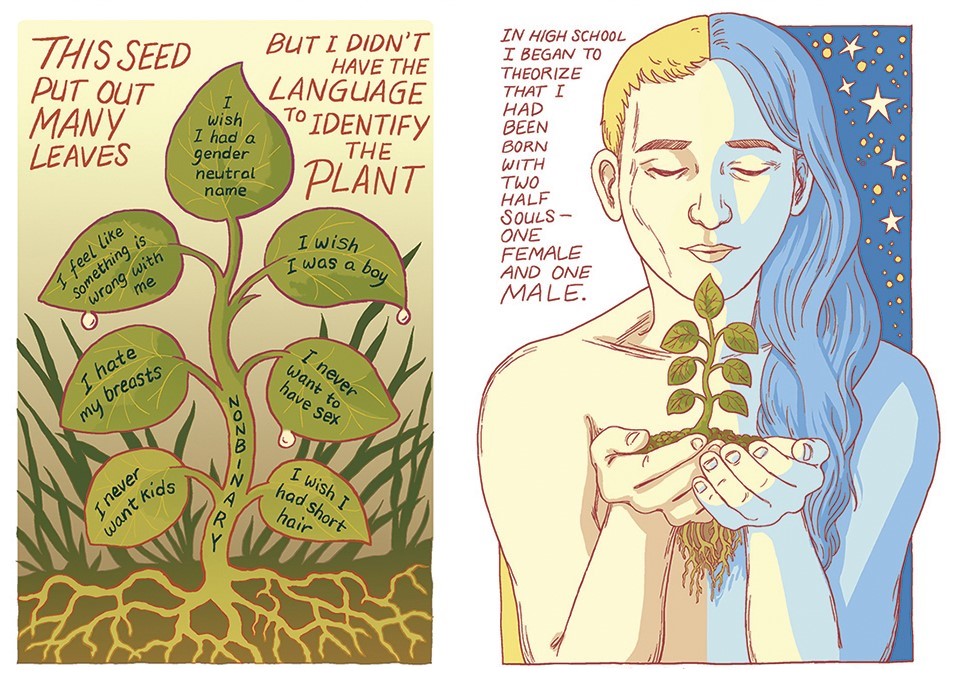

Gender Queer. By Maia Kobabe. Colors by Phoebe Kobabe. Sensitivity read by Melanie Gillman. Oni Press, ISBN 978-1549304002 (softcover), May 2019. $17.99. 240 pages. Glad to get to this one, at last. Gender Queer bills itself (on its cover) as both a memoir and a guide. It does both well. As a memoir, it is intimate, recounting a personal story about the push-pull of body and mind, self and society. It is as candid as it must be, as discreet as it can be. This is Maia Kobabe’s story, told with autographic frankness. As a guide, it gestures beyond the personal, giving an authoritative (though not universalizing) perspective on gender dysphoria, asexuality, and the politics of being a nonbinary subject in a binary culture. Actually, it works well as a guide because it works as a story — meaning Gender Queer is authoritative because Kobabe lived it. The book demonstrates how comics, by interweaving picture, word, and symbol, can evoke the general through the particular; how graphic memoir can do the work of political as well as autobiographical witness. Gender Queer credibly witnesses to tough issues precisely because Kobabe does not assume that anyone else has lived with those issues in precisely the same way; that is, the book honors the specificities of eir life (Kobabe uses the Spivak pronouns e, eir, and em). The quirks of eir own experience make the book what it is—yet sharing those quirks brings a vivid honesty that will speak to readers whose circumstances are very different from the author’s. Gender Queer is bookended by scenes of teaching and learning. In the opening, Maia struggles with eir autobiographical cartooning class, taught by MariNaomi (part of eir Comics MFA at the California College of the Arts); e resists the idea of sharing eir “secrets” on the page. Overcoming that resistance is prerequisite to the very book we are reading, and Kobabe depicts eirself tearing away a kind of veil to share eir story with us. In the closing, Maia teaches eir own comics workshop to tweens and teens at a local library, but struggles again: e reproaches eirself for not coming out to eir students, that is, not sharing eir nonbinary identity and preferred pronouns. Oddly, then, this coming-out story ends with an instance of not coming out, and of self-blame. The book is open about troubles and misgivings of this sort, as well as the familial and social awkwardness of negotiating new pronouns. In one striking scene, Maia’s aunt, a lesbian and committed feminist, responds to the pronoun question by challenging Maia’s perspective on FTM transitioning and genderqueerness, suggesting that these things may stem from misogyny, from a “deeply internalized hatred of women” (195). Maia is troubled by this challenge, of course, but the scene plays out with a delicate touch (eir aunt is properly supportive, not an adversary). Thus Kobabe is able to field a sensitive question, perhaps even to defuse the likely skepticism of some readers. I confess that these admissions of awkwardness and trouble swayed me; it was good to see Kobabe dealing with the struggles of family and friends without rancor or caricature. Gender Queer is that kind of book: humanly complicated, and willing to lean into complexity and trouble (it pairs well with L. Nichols’s Flocks in that regard). As an autographic, testimonial comic, Gender Queer adds to the fund of helpful cultural resources available to queer and gender-nonconforming young people. At the same time, it testifies to how Kobabe has drawn upon cultural resources in eir own journey: books, comics, Waldorf schooling, homeschooling, and art teachers (two depicted here, MariNaomi and Melanie Gillman, are queer cartoonists themselves). In Maia’s quest for self-understanding, books loom large: e is a voracious and self-documenting reader, a lister of books read and re-read. Kobabe’s account suggests that storytellers such as Neil Gaiman, Tamora Pierce, and Clamp served eir as resources for self-fashioning. A now-poignant passage recounts how Maia, a delayed reader at age eleven, taught eirself to read so as to devour the Harry Potter books (the irony of which, at the present moment, cuts like a knife). At a key moment late in Gender Queer, Kobabe turns to another book, neurophilosopher Patricia Churchland’s Touching a Nerve: The Self as Brain (2013), and even conjures Churchland as a character, an expert witness whose testimony about “the masculinizing of the brain” affirms Maia’s sense that “I was born this way.” This flourish is perhaps a touch too triumphant: Kobabe gives no sense of the intellectual debate around Churchland’s ideas, but simply invokes her as a bookish authority and solution. In any case, Gender Queer is, through and through, the record of a reader’s life. Style-wise, Gender Queer favors spareness and economy. Scenic backgrounds are few, and deliberate; Kobabe’s panels often consist of head shots against color fields. Conversation, reflection, and expression are everything. Pages typically follow a grid, whether unvarying or, more often, a bit relaxed, letting the white of the page show through: On the other hand, Kobabe lets rapturous, full-page drawing take over every so often. Clearly, eir minimalism is a considered choice, as confirmed by certain passages that break with the general sparseness. Dig for example these two facing pages: Though Gender Queer is discursive and text-filled, it never feels clotted. Kobabe’s organic hand-lettering and use of unbordered elements give the art breathing room. The pages include telling pauses, open bleeds, and dialogic exchanges that add up to a accessible, even brisk, read. Disarming is a good word for Gender Queer: the book’s honesty about dysphoria and bodily phobias may trouble some readers. I myself started the book in, admittedly, a guarded or hard-hearted mood, skeptical of the family ethos depicted: the utopian, back-to-the-woods values, the homeschooling, every little thing that I could interpret as a sign of sheltering or self-indulgence. Of course I was being pigheaded, and wrong — as the book’s warmth and complexity so clearly showed me. Gender Queer is moving and informative, an invaluable memoir and guide.

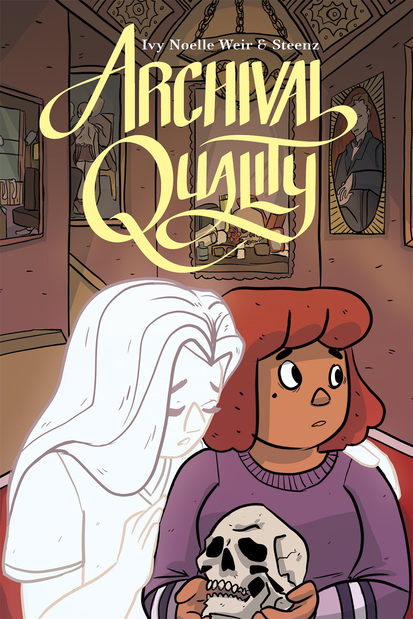

Sadly, this blog has been temporarily waylaid by academic duties (insert drawn-out Schulzian sigh here). However, I can poke my head out of the ostrich hole long enough to report, albeit belatedly, that the graphic novel Archival Quality (Oni Press, 2018), by Ivy Noelle Weir and Steenz, recently worn the 5th Annual Dwayne McDuffie Award for Diversity in Comics given out at the Long Beach Comics Expo. Geoff Boucher had the news, at Deadline Hollywood, back on Feb. 15. I'm sorry I didn't catch this fast enough! I reviewed Archival Quality last March. This year's other nominees for the McDuffie Award for Diversity were: Papa Cherry by Saxton Moore and Phillip Johnson (Pixel Pirate Studio), Exit, Stage Left!: The Snagglepuss Chronicles, by Mark Russell and Mike Feehan (DC), Destroyer by Victor LaValle and Dietrich Smith (BOOM!), and The Carpet Merchant of Konstantiniyya by Reimena Yee (self-published, about which, more here).

The Tea Dragon Society, by Katie O’Neill. Oni Press, 2017. ISBN 978-1620104415. 72 pages, hardcover, $17.99. Designed by Hilary Thompson. A gentle, winsome fantasy set in an unspecified secondary world with hints of backstory, The Tea Dragon Society is a lush, verdant, lovely thing: an exquisitely rendered, Miyazaki-esque idyll full of greenness and life. Testimony to a very specific set of passions, the book practically elevates cuteness—in the form of miniature, catlike dragons who have to be coddled and protected—to a moral good. In this world, traumas and losses have happened in the past, to be sketched in via poetic flashbacks, while the present action has a quiet, almost palliative quality (absent Miyazaki’s occasional hardnosed gift for terror and trial). The artwork conjures forms and volumes through blocks of color rather than heavy linework, and makes me swoon from its sheer gorgeousness. Aesthetically, then, the book as Object fairly mesmerizes me, though I confess that the ingratiating sweetness of the conceit, the world and its dragons, wears on me a little. Call me a grouch. Ironically, this handsome, bookish book began as a webcomic. I say ironically because The Tea Dragon Society is a heartfelt paean to traditional crafts—blacksmithing, dragon-tending—and the people who keep those crafts alive, passing on skills and techniques but also, most importantly, memories, both personal and cultural. The protagonist, Greta, a young smith in training, rescues a lost tea dragon and finds herself entering a new world of dragon-keeping, one of utmost delicacy. Tea dragons literally grow tea leaves from their horns, leaves that can be harvested only with a knowing, gentle touch. The tea brewed from said leaves brings back memories: to drink tea dragon tea is to reexperience the past, in quiet reverie. Dragon-keeping and tea-making are slow arts, requiring patience, precision, subtlety, and empathy. There’s a strong suggestion of Japan’s traditional craft (kogei) and art forms, forms bound up in the succession of generations, in the spirit of particular places, and in the relationships between mentors and pupils. Greta comes to know two dragon-keepers: a couple of former adventurers, now settled, who are striving, in defiance of cultural change and time, to keep the tea dragon tradition alive. She also meets the keepers’ shy, enigmatic ward, Minette, a girl who, it turns out, was once a prophet. Love between the two keepers, as well as the possibility of love between Greta and Minette, is romantic and idealized, queer-affirming, and chaste but not timid (i.e. the romance, though never earthy, is more than implicit). Gender conventions are flouted at every turn, albeit gracefully. The book strikes me as aesthetically genderqueer, its characters always beautiful and its art sensuous, yet it’s entirely, as we say, child-friendly: a quiet ecotopia of loving connection and small, tender gestures. Like its dragons, The Tea Dragon Society has about it an air of preciousness and fragility. The story is based on a pretty frail concept—albeit one elaborately explained in the book’s back matter—and readers unmoved by the bonding of dragon and caregiver may find the tale twee and oversweet. The logic of the story’s world frankly seems rigged so that O’Neill’s particular interests, dragons and tea, can together serve as a metaphor for the way that craft traditions preserve cultural memory. There’s a tidiness about the conceit that isn’t quite believable: tea dragon tea leaves only evoke memories shared by dragon and owner, meaning that the dragons do not pass on memories of their own, but only those experienced by the bonded pair of dragon and caregiver. Dragons rarely bond with each other as strongly as they do their caregivers, and so the social lives of these creatures are bound up in the dyadic closed circuit of dragon and owner. This is a tad too perfect, I’m tempted to say—something like a cat-lover’s daydream. In that sense, The Tea Dragon Society hovers between a credible fantasy world and an indulgence as delicate as spun glass. (It’s easy to be cynical about a story in which petting, pampering, and bonding with small, cute creatures makes everything happen.) Yet the pairing of Greta and Minette—one a crafter of memorable things, the other a fallen prophet who has lost most of her memories—gives the theme of remembering a special urgency, and the bonding of the two makes for an unusual love story. Further, O’Neill’s cartooning, especially her delineation of form through color, creates an immersive visual world that is delightful to visit. The sequences of shared memory include some wonderfully organic layouts, and the book is a treat to page through and reread. Finally, I have to admire the book’s determined emphasis on working and making, so different from what we’ve been conditioned to expect from fairy tales. I am perhaps too old and curmudgeonly for the story of The Tea Dragon Society. I admit, I’d like a world that resists and confounds its characters a bit more, something spikier and less comforting. But I’ll be sure to queue up for O’Neill’s next book (reportedly due out soon). She has the power of worldmaking and her narrative drawing is clear, graceful, and transporting. One of the charms of comics is the way the form invites us into private worlds, and The Tea Dragon Society does that beautifully.

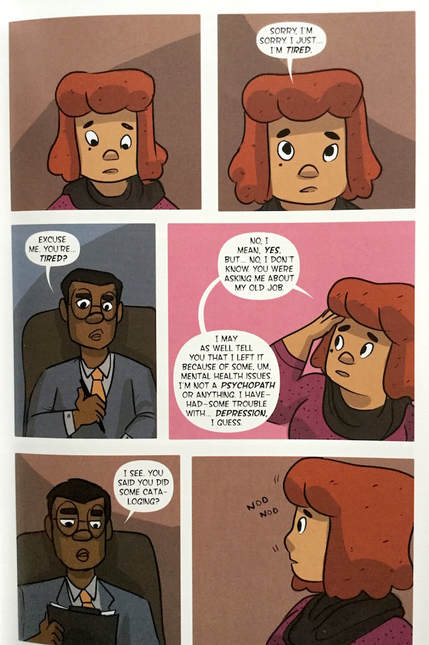

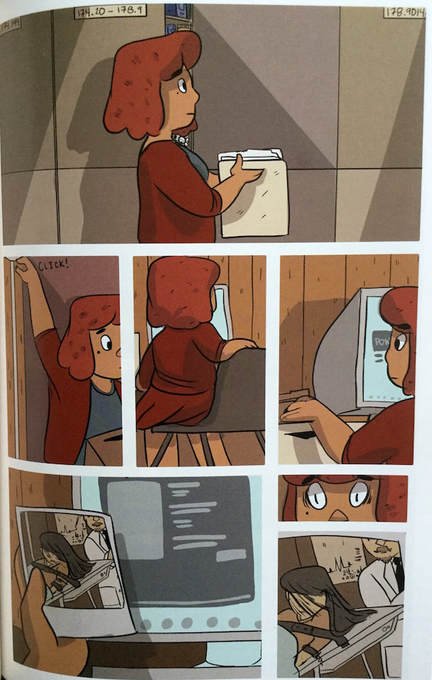

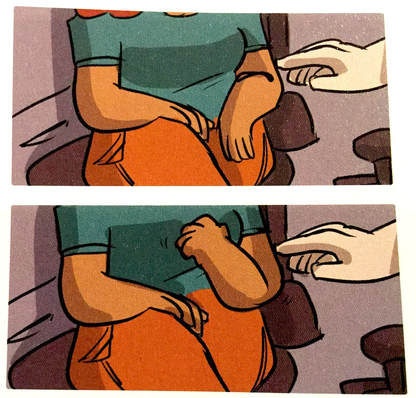

Archival Quality. Written by Ivy Noelle Weir, illustrated and colored by Steenz. Oni Press, March 2018. ISBN 978-1620104705. $19.99, 280 pages. A Junior Library Guild Selection. Archival Quality, an original graphic novel out this week, tells the story of a haunted museum: a ghost story. It also tells about living with mental illness. The protagonist Cel, a librarian struggling with anxiety and depression, takes a job as archivist of a spooky medical museum that once served as an asylum (my friend, medical archivist and comics historian Mike Rhode, should check this out). The catch: she has to live in an apartment on the premises and do her work only in the dead of night. Soon she begins to witness... happenings that she cannot explain. Her boss, the museum's curator, and her coworker, a librarian, tiptoe around her, knowing more than they will say. Cel, who lost her previous job due to a breakdown, is understandably perplexed and triggered by their evasions, and by the fact that no one seems to believe her reports of odd doings. She begins to have frightful dreams: flashbacks that evoke the shadowy history of women's mental health treatment. The plot, which like many ghost stories gestures toward the fantastic (as Todorov defined it), finally veers toward the outright marvelous as Cel investigates the case of a young woman from long ago whose presence still lingers about the place. Cel, as she works to solve that case, is by turns fragile and angry, defensive and determined—a complex character, as is the curator, at first her foil, later her ally. The story takes quite a few turns. To be honest, Archival Quality's title and look did not prepare me for its uneasy exploration of mental health treatment—or rather, the social and psychiatric construction of mental illness. As I read through the novel's first half, Steenz's drawing style struck me as too light, undetailed, and schematically cute for the story's atmosphere of updated Gothic. Cel, with her snub nose, button eyes, and moplike hair, reminded me strongly of Raggedy Ann, and in general Steen's characters have a neotenic, doll-like quality. The settings seemed too plain to conjure up mystery and dread; the staging seemed too shallow, with talking heads posed before blank fields of color or swaths of shadow, lacking particulars. Steenz favors air frames (white borders around the panels, rather than drawn borderlines) and an uncluttered look. This did not jibe with my expectations of the ghost story as a genre. But as the plot deepens, and Cel's dreams and visions overtake her, Weir and Steenz together generate suspense. The pages deal out a number of small, quiet shocks: Further, Steenz's sensitive handling of body language brings the characters, doll-like as they are, to life. The book becomes tense, involving, and, as we say, unputdownable. Weir and Steenz's back pages tell us that the two enjoyed a close working relationship, and you can tell this from the story's anxious unwinding. This is unusually strong storytelling, and a complicated, coiled plot, for a first-time graphic novel team. Clearly, Weir and Steenz are simpatico artistically—and ideologically too, I think, sharing a progressive and feminist outlook that shapes cast, character design, characterization, and plot. I will admit that not everything about Archival Quality works for me. The plot, on the level of mechanics, seems juryrigged and farfetched, that is, determined to pull characters and elements together for the sake of symbolic fitness, without the sort of realistic rigging that the novel seems to be striving for. In other words, certain things happen simply because they have to happen. Further, some elements of the story, rather big elements I think, are palmed off in the end because Weir and Steenz don't seem to be interested in working out the details. At the closing, I had the feeling that a Point was being made, rather than a novel being rounded off (to be fair, I often react this way to YA fiction, even though I know that didacticism is crucial to the genre). Still, Archival Quality, behind its coy title, offers a gutsy exploration of mental health treatment, an eerie ghost story, and characters who renegotiate their relationships with credible human frailty and charm. A most promising print debut, and a keeper.

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed