|

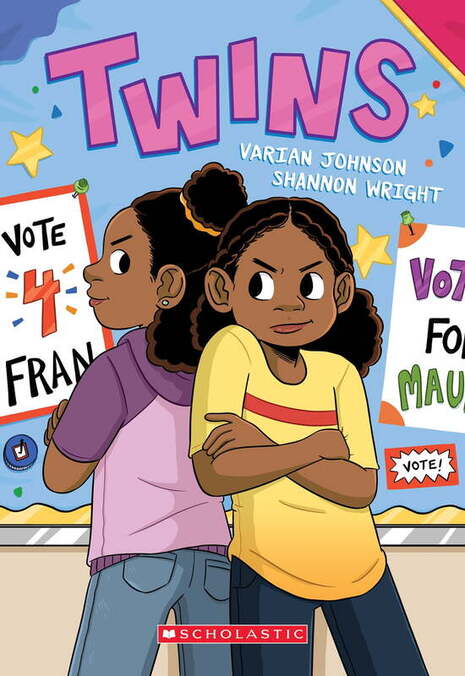

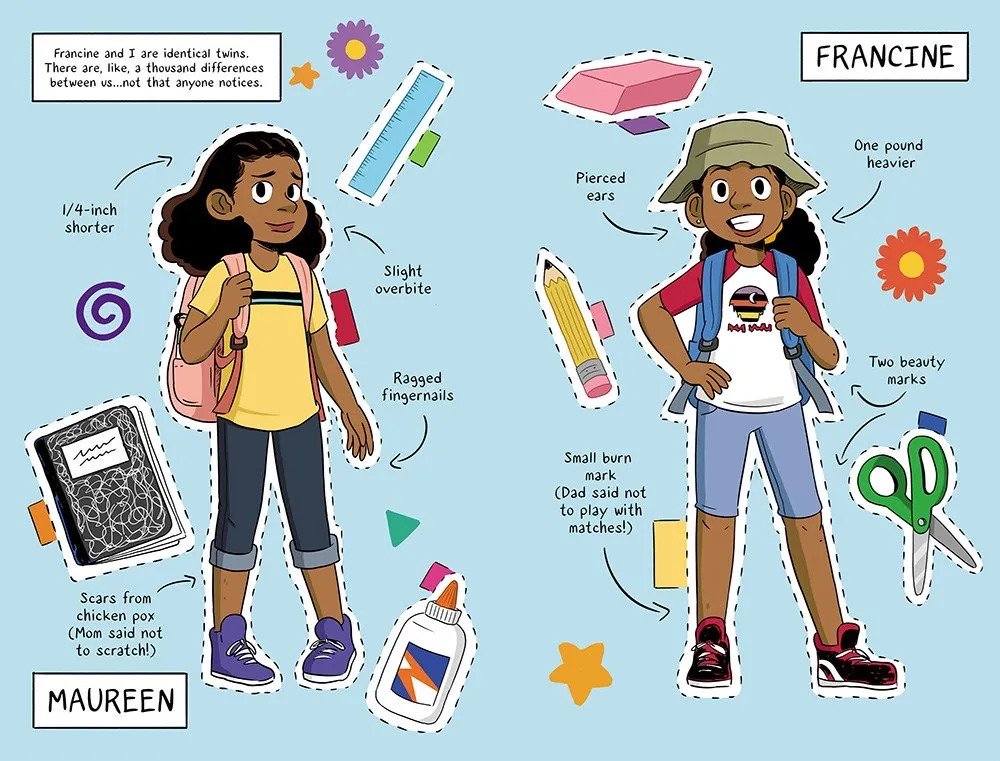

Twins. By Varian Johnson and Shannon Wright. Scholastic/Graphix, ISBN 978-1338236132 (softcover), 2020. US$12.99. 256 pages. Last week I belatedly read Twins, a much-praised middle-grade graphic novel published by Scholastic in 2020 — a first graphic novel for both writer Varian Johnson, who is a prolific novelist, and artist Shannon Wright, who has illustrated a number of picture books (most recently, Holding Her Own: The Exceptional Life of Jackie Ormes). Twins is good, but left me wanting more. The plot concerns identical twin sisters, Maureen and Francine, who have always been close but begin to pull apart as they enter sixth grade. They end up running against each other in a student body election, a rivalry driven by mixed or confused motives that hurts their relationships with friends and family. The book boasts many nicely observed, sometimes poignant, details: novelistic good stuff. The plotting balances the twins' need for individuation against their strong bond, with a sense of earned insight for both sisters. There are astute cartooning choices along the way, including full-bleed splash pages that capture moments of struggle, hurt, and growing realization. Compositionally, Wright delivers, with emotive characters, startling page-turns, and a confident grasp of what's at stake dramatically. Twins, I admit, strikes me as more reassuring than challenging. It's on familiar middle-grade turf, with a story of girls becoming tweens and growing more sensitized to social nuances and strained friendships. There are soooo many graphic novels currently working this turf. The setting is anodyne: a comfortably middle-class suburbia with dedicated students, supportive teachers and families, wise parents, and lessons on offer about self-discipline, self-confidence, and leadership. Loose ends are tied and every arc resolved, or at least reassuringly advanced, by book's end, with no one coming off the worse. Some elements, however, seem under-thought or cliched — for instance an ROTC-like "Cadet Corps" at the school, a plot device that allows for a fierce, drill sergeant-like teacher and moments of tough discipline for the more timid of the two sisters, who of course comes out the stronger (but oh the unexamined militaristic overtones). The book is inclusive and aims to be progressive, focusing on protagonists of color (Maureen, Francine, and their family are Black) while downplaying the usual generic thematizing of racism and classism as "problems" to be suffered through (a tendency expertly spoofed by Jerry Kraft in New Kid). One scene deals with shopping while Black and implies a critique of unspoken racism, but that thread isn't woven through the whole book. That in itself might be refreshing; the book thankfully avoids potted depictions of racialized suffering and trauma. Yet for me there is too little sense of social or institutional critique; the twins' relationship and personal growth are the main things, to the point of presenting adult choices uncritically and tying up the story without any lingering sense of mystery or depths remaining to be plumbed. In a word, it's pat. Perhaps I'm guilty of wanting this middle-grade book to be more YA? That wouldn't be fair, of course. But Twins is one of so many recent graphic novels that, from my POV, appear boxed in by children's book conventions, more specifically by the rush to affirm and reassure. The contours of this kind of book are starting to seem not just clear, but rigid. Young Adult books too have their conventions, one being skepticism of adult choices and institutions, and I don't know if I'm asking for that. Perhaps what I'm wishing for is something else: a touch of mystery, maybe, or a respect for the unfinished business of living. Twins is a traditional tale well told, with all its arcs well finished and its major characters affirmed and advanced. I just can't imagine re-reading it for pleasure. Some readers will stick to the book like glue, I expect. The characterization of the twins is complex, and Maureen, who is the book's focal character and real protagonist, is especially well realized: a socially anxious nerd and academic overachiever but not a shrinking violet, not a cliché. Johnson and Wright know these characters and treat them kindly; their dialogue clicks. Plus, the art is full of smart touches, and Wright offers clear, crisp cartooning and dynamic layouts throughout. Some moments registered very strongly with me: for example, the scene early in the book where Maureen and Francine get separated at school and a page-turn finds Maureen stranded in a teeming crowd of other kids, lost. Yet the book's brightness and formulaic coloring, which favors open space, solid color fields, abstract diagonals, and color spotlights, strike me as simply functional, and in the end more busy than harmonious. While Wright excels at characters, the settings appear textureless and a bit bland. Her page designs are restless, inventive, and clever, the storytelling clear, yet the governing sensibility seems, again, generic to my eyes. It's right in the pocket for post-Raina middle-grade graphic novels, but doesn't grip me. The middle-grade graphic novel is one of the most robust areas in US publishing, and the novel of school, friendship, and social navigation is its nerve center. Twins is a fine example of that. I think I'm becoming more and more jaundiced about that kind of book, though. I can now see the outlines of a formula, and I'm getting jaded. I admit, this realization has me rethinking the bright burst of enthusiasm with which I began Kindercomics five years ago.

0 Comments

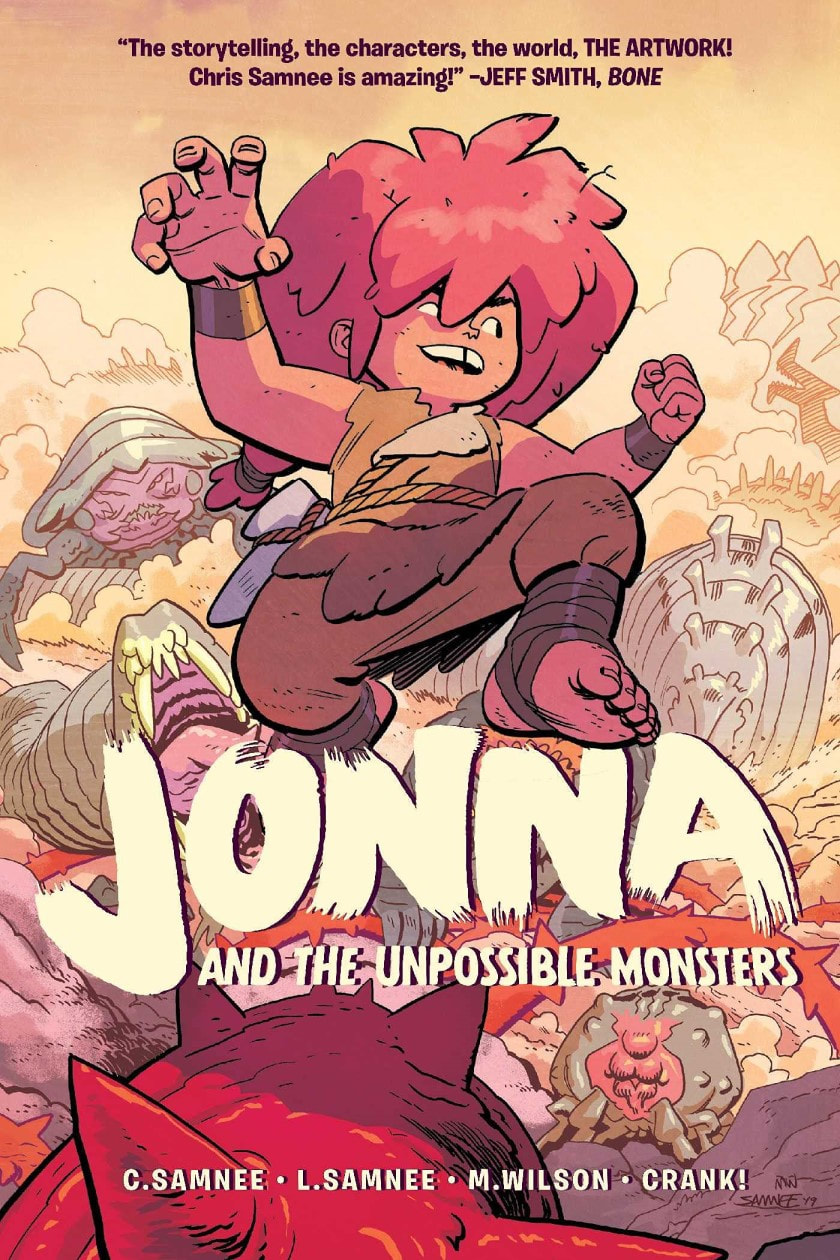

Jonna and the Unpossible Monsters. Book One. Written by Chris Samnee and Laura Samnee. Drawn by Chris Samnee. Colors by Matthew Wilson. Lettering by Crank! (Christopher Crank). Oni Press, August 2021. ISBN 978-1620107843, $US12.99. 112 pages. Jonna and the Unpossible Monsters has a premise that was just waiting to happen, one that somebody, somehow, had to get around to: a postapocalyptic children's fantasy about fighting giant, kaiju-like monsters. There's a touch of Jack Kirby's Kamandi, the Last Boy on Earth about this, and maybe a touch of Pacific Rim too. Co-creators Laura Samnee and Chris Samnee describe Jonna as a story they "could share with [their] three daughters," something created "for them" but also "inspired by them"; the comic, though, will appeal to action-starved fans of Chris Samnee's work on such superhero comics as Thor the Mighty Avenger, Daredevil, Black Widow and Captain America (or his current martial arts fantasy with writer Robert Kirkman, Fire Power). The heroic Jonna is a wild, monster-clobbering girl with a whiff of Ben Grimm or Hellboy. She comes across as untrammeled, almost feral, yet delightful. When Jonna goes missing in a ruined, kaiju-ravaged world, her older sister Rainbow – the more fretful, responsible one, naturally – tries to find her, then corral and (re)civilize her. Jonna, though, remains a unpredictable force of nature. You don't need to know much more; the first half dozen pages give you whopping big monsters, and plenty of synthetic worldbuilding. There's a sense of the familiar about all of it, but novelty and excitement too. By now it's almost a cliché to speak of Chris Samnee's masterful storytelling and sheer chops (I've paid tribute before). It is true that I will read just about anything drawn by him, especially when it's colored by Matt Wilson, his steady collaborator for more than a decade. Granted, I got impatient with Fire Power within a few issues. Though I dug its bang-up start, Fire Power strikes me as a shopworn White martial arts fantasy à la Iron Fist; it's tropey, and conceptually a bit tired. I've stayed with it, however, because of Samnee and Wilson's visuals, and it has become my monthly dose of old-school craft and loveliness, balancing breathless action with an Alex Toth-like elegance. Samnee manages to be polished and rugged at once; his drawing offers classicism and grace, but with a terrific infusion of energy. Jonna, I think, may be the best thing he has ever done: the pages sing, and roar, and astonish with their gusty action and playfulness. Freed somewhat from the stylized naturalism of mainstream superhero comics (though that skill set is still very much in evidence), Jonna cartoons with a joyful freedom. Wilson's coloring, too, is eye-wateringly good. All this is my way of saying that Jonna is craftalicious and affords plenty of gazing and rereading pleasure after the initial readerly sprint. But what does it amount to? On some level, it remains a kind of superhero comic, not only because Jonna packs a mean punch but also because a couple of other characters discovered along the way, Nomi and Gor, are seasoned fighters as well (Nomi boasts powerful prosthetic arms). So, this is a slugfest. But there's more: moments of poignancy, sisterly anxiety, and Jonna's weird, ferine energy and charming social cluelessness. And the Samnees allow a certain melancholy to creep in; the world of Jonna is a fallen one, full of sundered families, lost loved ones, bereavements. In one scene, a ragtag group of survivors huddles around a fire, and their dialogue says a lot: My whole family gone. My home destroyed. My village destroyed. Everything destroyed. Without pressing the point, the story has a genuinely apocalyptic feel that, to me, reeks of COVID. That it manages to be cockeyed and funny at the same time is no small feat. Though billed as a children's story, Jonna is just as much for grownups. The book (originally serialized in floppy form) splits the difference between direct market-oriented cliffhanger series and middle-grade graphic novel, so it's courting multiple audiences. Moreover, a theme of "families and belonging" (as the Samnees put it) threads through the book, familiar from many an animated family film, and like such films Jonna offers adults a kind of reassurance even as it aims for kids. That is, it offers childhood as a cure for ruin and heartbreak. The basic ingredients are familiar – there's nothing revolutionary about this tale – but I'm at a time in my life where seeing kids wallop monster does me a world of good. This first volume (a second is promised for Spring 2022) sets up some mysteries, not least the mystery of Jonna herself, and doesn't answer very many questions, but I enjoy paging through it and rereading it. In fact, I enjoy it more than I can say. PS. The excellent magazine PanelxPanel, by Hass Otsmane-Elhaou and company, devoted a good chunk of its May 2021 issue (No. 46) to Jonna, and includes a revealing interview with Chris Samnee. Plus, the issue contains other articles on depictions of children and on young readers' graphic novels. Well worth checking out!

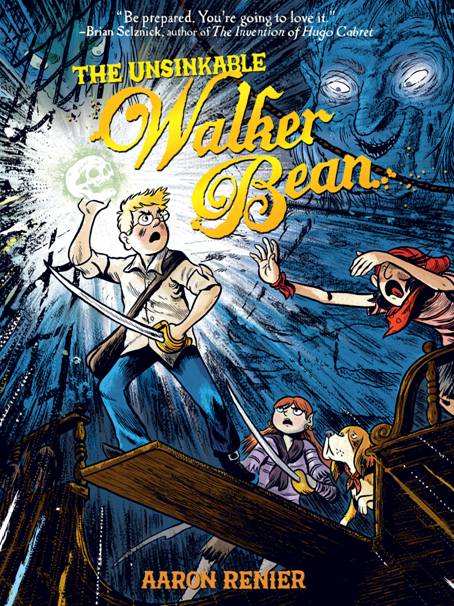

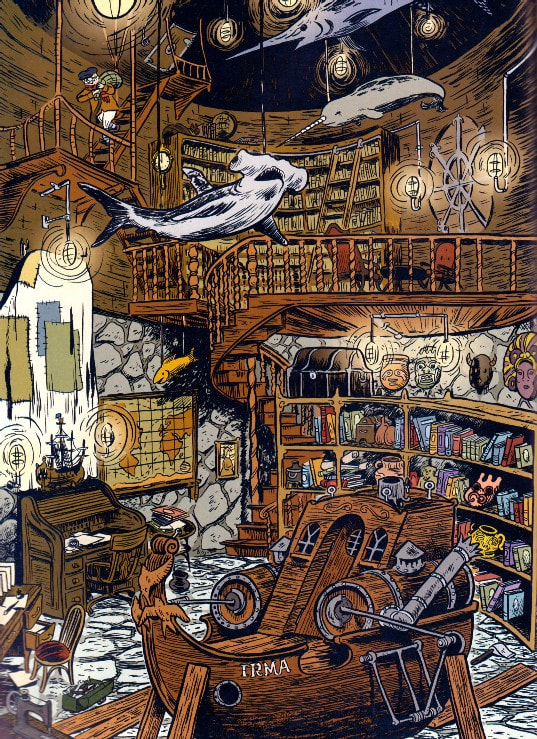

The Unsinkable Walker Bean. By Aaron Renier. First Second, 2010. ISBN 978-1596434530. 208 pages, softcover, $15.99. Colored by Alec Longstreth. (This review originally ran on the now-defunct Panelists blog in June 2011. I've revived it here and now because a sequel to Walker Bean is promised this fall. Ever the fusspot, I have not been able to avoid the temptation to trim and update, albeit slightly. - CH) Piracy on the high seas—storybook piracy I mean, the kind we know mostly from echoes of Stevenson and Barrie—remains an adaptable, nigh-bottomless genre. The piratical yarn lends itself to the dream of an infinitely explorable world, to lusty romance, oceanic myth, and shivery deep-sea terrors, all of it salted with enough bilge, filth, and real-world cynicism to sell even the flintiest skeptic. The golden age of Caribbean piracy, which even as it happened was a set of facts angling to become a myth, helped redefine the pirating life as radically democratic, an anarchic space of freedom—ironic, since it grew out of colonialism and the Thirty Years’ War. That age bequeathed us a roll call of larger-than-life persons, Calico Jack, Anne Bonny and Mary Reade, Blackbeard, and the rest: real-life opportunists from whence Stevenson distilled his great, demonic “Sea-Cook,” Long John Silver, Treasure Island’s indelible villain. Silver’s slipperiness lives on, I suppose, in Johnny Depp’s Jack Sparrow, ever scheming, ever sidling away to scheme another day. Pirates of the Caribbean reinvigorated the old genre, but with a heaping dose of hypocrisy. For example, in Bruckheimer, Verbinski, and Depp's third Pirates film (2007), the multinational juggernaut that is Disney pits globalization, in the person of the über-capitalistic East India Company, against scrappy piratical “freedom,” represented by Sparrow and his fellow rum-soaked scumbags. Huh? Couched in terms of post-9/11, post-Patriot Act resistance to a neoliberal mercantilist New World Order, that movie of course made shiploads of money. Such irony. So, the myth of the high-seas pirate carries on, its popularity an index of how we feel about the tug o’war between hegemonic authority and the individual will to live and indulge. Cartoonists in particular seem to love pirate tales and other nautical yarns, maybe because such tales make the world feel larger, maybe because they give license for scruffiness and odd character design (think Segar), maybe simply because the high seas invite so much gushing ink. A fair handful of graphic novels from recent times either plunge into the deep sea or sail off to faraway places: Leviathan, That Salty Air, Far Arden, The Littlest Pirate King, Blacklung, Set to Sea, et cetera (I bet readers can name a few others). Aaron Renier’s The Unsinkable Walker Bean (released, what, eight years ago now?) dives into the genre with a hectic, dizzying 200-page story and a surplus of delicious inky craft. Written and drawn by Renier and colored by Alec Longstreth, Bean is a beautiful, odd book aimed squarely at young readers, the first of a promised series that, it seems to me, aims to mix a carefully rigged Tintin-esque plot with the jouncing unpredictability and eccentricity of Joann Sfar, whose organic approach to both plotting and drawing probably provided inspiration. The materials are familiar enough, but the execution is, wow, crazy. The results strike me as imperfect but delightful. Walker Bean (a cartoonist’s surrogate?) is an unlikely pirate: a nervous, sensitive boy prone to doodling and mad invention, slightly pudgy and bespectacled to make him seem an unexpected hero. His emotions are worn near the surface. The plot tests his ingenuity and bravery, offering plenty of swashbuckling and catastrophic violence in the bargain. It’s sometimes bloody and boasts some real scares. Walker’s world looks like a farrago of eighteenth and nineteenth century elements—costume, settings, ships—but frankly it’s unreal, a synthetic alternate world. Per the map on the frontispiece, that world is like a distorted view of ours but bears fanciful names (e.g., Subrosa Sound, the Gulf of Brush Tail, and cities like New Barkhausen and Tapioca) alongside real ones like the Atlantic and Mediterranean. Anachronisms abound, such as a middle class child’s bedroom casually appointed with books. Stops along the way, such as the colorful port of Spithead, teem with diverse character types who lend the storyworld a distinctly postcolonial vibe. The plot, a mad, churning mess, begins with mythical backstory: a child’s bedtime story about the destruction of Atlantis. Then it veers sharply into pure breathless adventure. Young Walker, to save his ailing grandfather, must brave the high seas in order to return a maleficent artifact to its home in a deep ocean trench. That artifact is a skull of pearl formed in the nacreous saliva of two monstrous sea “witches”: huge lobster-like monsters who caused Atlantis’s fall. The skull is itself a character, evil, cackling, and seductive. One glimpse of it can send a person into shock or even death. Walker’s grandfather, an eccentric, bedridden admiral, entreats the boy to dispose of the skull, while Walker’s father, Captain Bean, a vain, greedy fool, plots to sell the skull for maximum profit, egged on by one “Dr. Patches,” a fraud and a fiend. The action, which zigzags unpredictably, includes long stretches on a pirate ship called the Jacklight. There Walker becomes an unwitting crew member, working with a powder monkey named Shiv and a girl named Genoa—an able thief and fighter who more than once nearly kills Walker. That's as close as the book gets to the excitements of courtship. The pearlescent skull is said to be a source of great power, of course, but keeps tempting would-be possessors to their doom (there’s a strong hint here of Tolkien’s one Ring). Donnybrooks and sea battles alternate with creepy scenes of the skull exerting its influence and big, splashy encounters with the horrific witches. Pages vary from minutely gridded exercises to explosive full-bleed spreads. Plot-wise, there are double-crosses, shipwrecks, and weird critters aplenty, a burgeoning cast of supporting players, and moments of tenderness, confusion, and self-realization. Walker, Gen, and Shiv are all well realized. Walker himself becomes the true hero that the title promises. In the end, things are resolved but other things left open, setting up Volume Two. Renier has not worked out his story perfectly. Honestly, I didn’t retain most of the plot details after reading through the first time; the story ran by me at a mile a minute, and I couldn’t catch it. The plot twists confusingly like a snake underfoot, and logical stretches are many; even for a pirate yarn, the book strains belief. At one point, the remains of a smashed ship conveniently drift into port. At another, the Jacklight, having been completely wrecked, is rebuilt and transformed into an overland vehicle (with wheels) in the space of a single day. In short, Renier leans on plot devices that don’t convince. What’s more, the storytelling is at times more exuberant than clear; certain double-takes and surprises confused me. Pacing and story-flow sometimes hiccup. What we’ve got here is a patently rigged plot set in an overstuffed story-world that is still in the process of being worked out. Walker Bean is a generous story, almost risibly full, but sometimes it's hard to believe. Ah, but how it testifies to the love of craft! The book’s colophon describes in detail Renier’s process of drawing and hand-lettering (on good old-fashioned Bristol board) and then the shared process of coloring (where the digital takes over). All tools and techniques are duly described, even razor-work and the use of Wite-out to vary texture. The descriptions are aimed at any reader; no prior knowledge of technique is assumed. It’s as if Renier and Longstreth wanted to let young readers in on their trade secrets. The book’s coloring, it turns out, began collaboratively: Using some old, faded children’s books for inspiration, Aaron and Alec created a custom palette of 75 colors, which are the only colors used in this book. Coloring a big book is easier when one has only a limited number of colors to choose from, and it makes the colors feel very unified. The results do exhibit an aesthetic unity, without disallowing the occasional eruption of tasty graphic shocks. In any case, the blend of line art and color—handiwork and digital—is gorgeous. Renier, if not yet a surefooted storyteller, is a terrific cartoonist. Vigorous brush- and pen-work, lush texturing and atmosphere, dramatic staging, complex yet readable compositions, and even formalist games—all these are in his ambit. Examples are legion. For instance, check out this panel depicting a bumpy ride: Or this much quieter one, depicting a secret hideout: Renier’s commitment to the work and talent for conjuring strange places and characters show in every page—and every page is different. This is first-rate narrative drawing, stuffed with beauty and promise; it takes the gifts shown in Renier’s first book, Spiral-Bound, and boosts them to a new level. Finally and most importantly, Walker Bean has soul. It makes room for emotional complexity. Minor epiphanies and finely observed silences, scattered across the book, make it much more than an opportune potboiler. Behind the book is a thumping heartbeat that testifies to a reckless love of comics and adventure. This is a yarn without a whiff of condescension: mad, high-spirited, and cool. (Volume Two is due this October. Hmm, what difference will eight years make? Also, note that KinderComics will be on summer break between now and Monday, August 20, 2018.

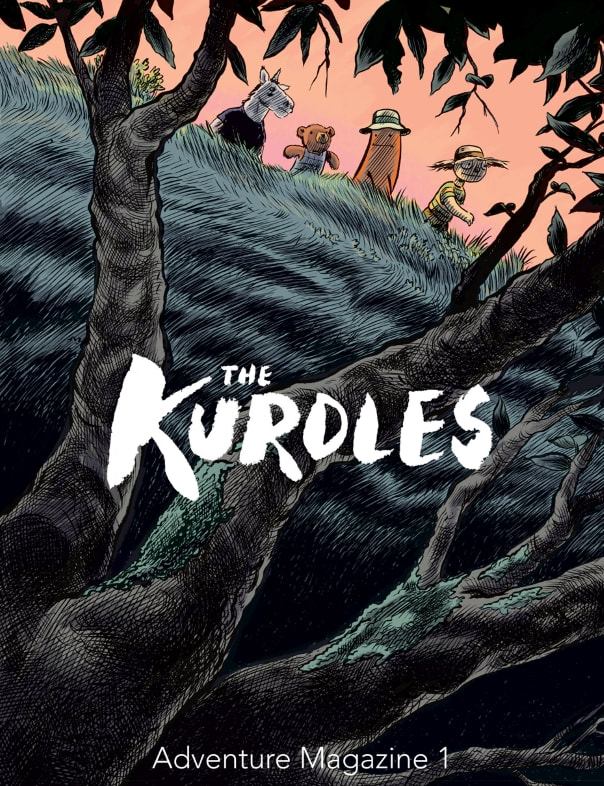

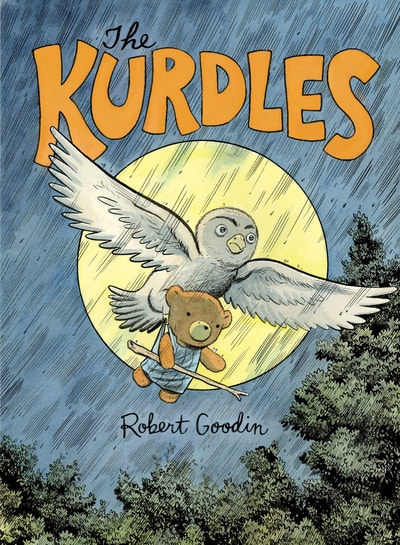

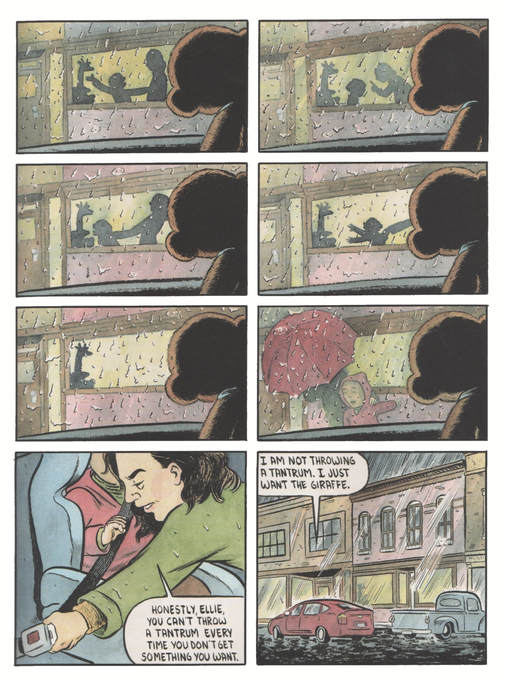

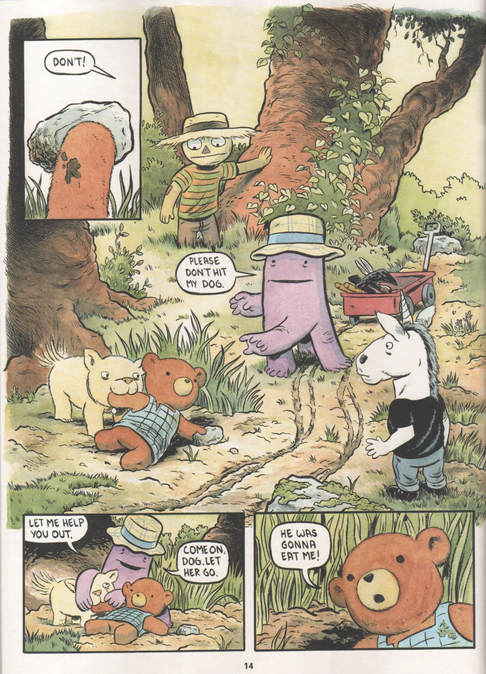

The Kurdles Adventure Magazine #1. Edited by Robert Goodin. Comics and other features by Robert Goodin, Andrew Brandou, Georgene Smith Goodin, Cathy Malkasian, and Cesar Spinoza. Fantagraphics, July 2018. 52 pages. The new Kurdles Adventure Magazine, brainchild of editor-cartoonist Robert Goodin, revisits the nonsensical world of Goodin’s graphic novel, The Kurdles (2015), with its eccentric characters, cockeyed story-logic, and gorgeous drawing. The Magazine’s 52 pages include half a dozen short stories and one-pagers starring the Kurdles (two of them reprints from anthologies) but also various stories and features by alumni of Goodin’s erstwhile micro-press venture, Robot Publishing: Cesar Spinoza, Andrew Brandou, and, probably the best known of the bunch, Cathy Malkasian (Percy Gloom, Eartha). These artists created deluxe minicomics for Robot back in the day, and generally hail from TV animation (Goodin’s day job, so to speak). The Magazine, then, not only carries on The Kurdles but also reaffirms Goodin’s bond with a small community of likeminded cartoonists. It’s a lovely, strange concoction that seems less like a children’s magazine, traditionally conceived, and more like an artist’s pet project. The Magazine offers new Pacho Clokey strips by Spinoza, a new Howdy Partner story by Brandou, and, strongest of the lot in my opinion, a lovely tale by Malkasian, “No-Body Likes You, Greta Grump.” It also offers, courtesy of Georgene Smith Goodin, a disarmingly complex set of directions for knitting one of the Kurdle characters, Pentapus (wow). Altogether, these features make for an odd, and defiantly uncommercial, mix. I found myself wondering who—besides me—this magazine is for. The Kurdles stories and pages here, Goodin’s, are sly and funny, reviving the quirky community of talking animals introduced in the graphic novel. Two of the stories, bookending the magazine, involve Sally the teddy bear (perhaps the series’s closest thing to a reader surrogate) asking questions about how color is perceived, and these become deliciously meta, in effect commenting on Goodin’s own choices as colorist and painter. These tales may bewilder readers unfamiliar with the graphic novel’s world, and are, well, pretty esoteric for first offerings from an “adventure magazine.” What can you say about a mag that begins with a story titled “Pentapus the Pentachromat”? In fact these stories didn’t quite “click” for me until I re-read the Kurdles graphic novel, and then re-read the stories—at which point their cleverness and characterizations made perfect sense. Readers who dig the Kurdles may wish for a much larger dose than what this first issue offers Malkasian’s “Greta Grump” concerns a mean, unhappy little girl who bullies a whole series of “rental” pets available at a pet shop until she finally meets her match in a blunt Seussian tortoise: a dapper, sharp-tongued Mr. Belvedere type who trades barb for barb and so bewilders the girl that he effectively disarms her. The relationship between Greta and “No-Body” is a tantalizing story engine, and Malkasian builds it with a light touch, avoiding didacticism even as she transforms Greta from a stock type, the little terror, into someone more shaded and interested. It’s a lovely, insinuating piece that has something to say about race (Greta is a white girl with parents of color who worries about not looking “like them”) but skirts the obvious moralisms, allowing its distinct comic twosome to get to know each other rather than worrying over the delivery of a Message. This is very promising work as well as a strong story in its own right. By contrast, Spinoza’s and Brandou’s contributions, though droll and distinctive, don’t seem to offer much in the way of future tales. When I reviewed the Kurdles graphic novel I marveled at its uncommercial and non-formulaic nature, its embrace of nonsense and defiance of conventional wisdoms. I suppose I have to say the same about this new venture. Goodin calls it an "independent, kid-friendly comic magazine," but frankly I can't see it working as a magazine in the traditional sense, and certainly not as a children's mag. Publication plans seem to call for just one issue a year, as the next issue is promised for summer 2019 (though perhaps the magazine is meant to speed up, once established?). Further, the first issue, while absorbing to this comics fan, does not offer a serial of the sort that the phrase “adventure magazine” brings to mind. Nor does it offer a succinct and enticing reintroduction to the world of Kurdles for those who have not read the graphic novel. While Fantagraphics is promoting this as the “best kids comic mag since the demise of Nickelodeon magazine,” it's really a world away from that model. The comics in it seem ripe for alt-comix anthologies of the Pood, Mome, or Now variety, rather than a mag that aims to be “kid-friendly” (though I'm not saying that the work is kid-unfriendly). The low frequency, lack of an anchoring serial (Goodin promises one starting in issue #2), and shortage of other interactive features besides comics (those knitting instructions do not strike me as kid-friendly) make The Kurdles seem like a long shot commercially, and I'm left to wonder if Goodin's Kurdles universe might best be served up in another venue, say in occasional issues of a more general comics anthology. Indeed the children's magazine format does not seem like the optimal vehicle for this work. Such a format needs to come out oftener, with a variety of appealing comics and non-comics features, such as activity pages, gag cartoons, and (I hate to say it) transmedia tie-ins. That’s what made the quirky comics section in Nickelodeon possible. Also, it should probably go without saying at this point that the direct market, which seems to be the primary market for this mag, is not the ideal matrix for a children's periodical. Despite some wonderfully eccentric comics, then--which will certainly lure me back for future issues—The Kurdles Adventure Magazine strikes me as a quixotic proposition at best. There's nothing wrong with that, but I do fear that the project will be hard to sustain without the kind of compromises that “kids' comic mags” usually entail. The Kurdles Adventure Magazine seems more likely to become an annual alternative comix booklet supported by diehards, as opposed to a kids' periodical with momentum, market presence, and a chance of making a dent in children's comics reading. Too bad, because a periodical with regular doses of Goodin and Malkasian is a wonderfully enticing prospect. Fantagraphics provided a digital review copy of this book. (Having seen it at last on paper, I have to say that the printed version wows me, color-wise. Paper suits Goodin's work!)

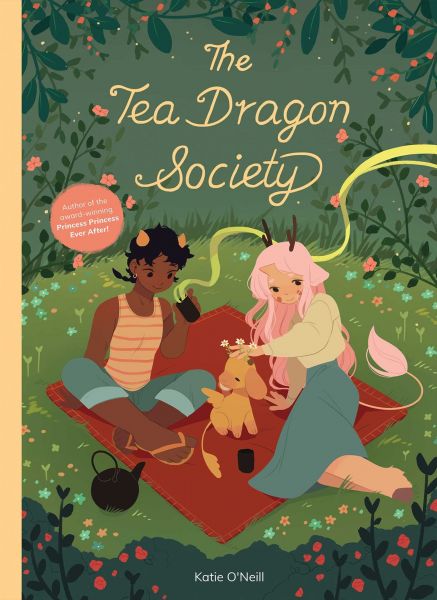

The Tea Dragon Society, by Katie O’Neill. Oni Press, 2017. ISBN 978-1620104415. 72 pages, hardcover, $17.99. Designed by Hilary Thompson. A gentle, winsome fantasy set in an unspecified secondary world with hints of backstory, The Tea Dragon Society is a lush, verdant, lovely thing: an exquisitely rendered, Miyazaki-esque idyll full of greenness and life. Testimony to a very specific set of passions, the book practically elevates cuteness—in the form of miniature, catlike dragons who have to be coddled and protected—to a moral good. In this world, traumas and losses have happened in the past, to be sketched in via poetic flashbacks, while the present action has a quiet, almost palliative quality (absent Miyazaki’s occasional hardnosed gift for terror and trial). The artwork conjures forms and volumes through blocks of color rather than heavy linework, and makes me swoon from its sheer gorgeousness. Aesthetically, then, the book as Object fairly mesmerizes me, though I confess that the ingratiating sweetness of the conceit, the world and its dragons, wears on me a little. Call me a grouch. Ironically, this handsome, bookish book began as a webcomic. I say ironically because The Tea Dragon Society is a heartfelt paean to traditional crafts—blacksmithing, dragon-tending—and the people who keep those crafts alive, passing on skills and techniques but also, most importantly, memories, both personal and cultural. The protagonist, Greta, a young smith in training, rescues a lost tea dragon and finds herself entering a new world of dragon-keeping, one of utmost delicacy. Tea dragons literally grow tea leaves from their horns, leaves that can be harvested only with a knowing, gentle touch. The tea brewed from said leaves brings back memories: to drink tea dragon tea is to reexperience the past, in quiet reverie. Dragon-keeping and tea-making are slow arts, requiring patience, precision, subtlety, and empathy. There’s a strong suggestion of Japan’s traditional craft (kogei) and art forms, forms bound up in the succession of generations, in the spirit of particular places, and in the relationships between mentors and pupils. Greta comes to know two dragon-keepers: a couple of former adventurers, now settled, who are striving, in defiance of cultural change and time, to keep the tea dragon tradition alive. She also meets the keepers’ shy, enigmatic ward, Minette, a girl who, it turns out, was once a prophet. Love between the two keepers, as well as the possibility of love between Greta and Minette, is romantic and idealized, queer-affirming, and chaste but not timid (i.e. the romance, though never earthy, is more than implicit). Gender conventions are flouted at every turn, albeit gracefully. The book strikes me as aesthetically genderqueer, its characters always beautiful and its art sensuous, yet it’s entirely, as we say, child-friendly: a quiet ecotopia of loving connection and small, tender gestures. Like its dragons, The Tea Dragon Society has about it an air of preciousness and fragility. The story is based on a pretty frail concept—albeit one elaborately explained in the book’s back matter—and readers unmoved by the bonding of dragon and caregiver may find the tale twee and oversweet. The logic of the story’s world frankly seems rigged so that O’Neill’s particular interests, dragons and tea, can together serve as a metaphor for the way that craft traditions preserve cultural memory. There’s a tidiness about the conceit that isn’t quite believable: tea dragon tea leaves only evoke memories shared by dragon and owner, meaning that the dragons do not pass on memories of their own, but only those experienced by the bonded pair of dragon and caregiver. Dragons rarely bond with each other as strongly as they do their caregivers, and so the social lives of these creatures are bound up in the dyadic closed circuit of dragon and owner. This is a tad too perfect, I’m tempted to say—something like a cat-lover’s daydream. In that sense, The Tea Dragon Society hovers between a credible fantasy world and an indulgence as delicate as spun glass. (It’s easy to be cynical about a story in which petting, pampering, and bonding with small, cute creatures makes everything happen.) Yet the pairing of Greta and Minette—one a crafter of memorable things, the other a fallen prophet who has lost most of her memories—gives the theme of remembering a special urgency, and the bonding of the two makes for an unusual love story. Further, O’Neill’s cartooning, especially her delineation of form through color, creates an immersive visual world that is delightful to visit. The sequences of shared memory include some wonderfully organic layouts, and the book is a treat to page through and reread. Finally, I have to admire the book’s determined emphasis on working and making, so different from what we’ve been conditioned to expect from fairy tales. I am perhaps too old and curmudgeonly for the story of The Tea Dragon Society. I admit, I’d like a world that resists and confounds its characters a bit more, something spikier and less comforting. But I’ll be sure to queue up for O’Neill’s next book (reportedly due out soon). She has the power of worldmaking and her narrative drawing is clear, graceful, and transporting. One of the charms of comics is the way the form invites us into private worlds, and The Tea Dragon Society does that beautifully.

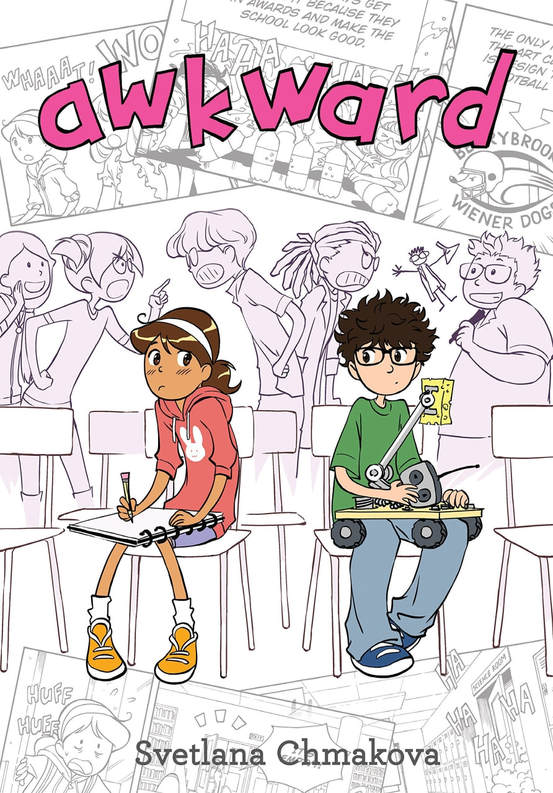

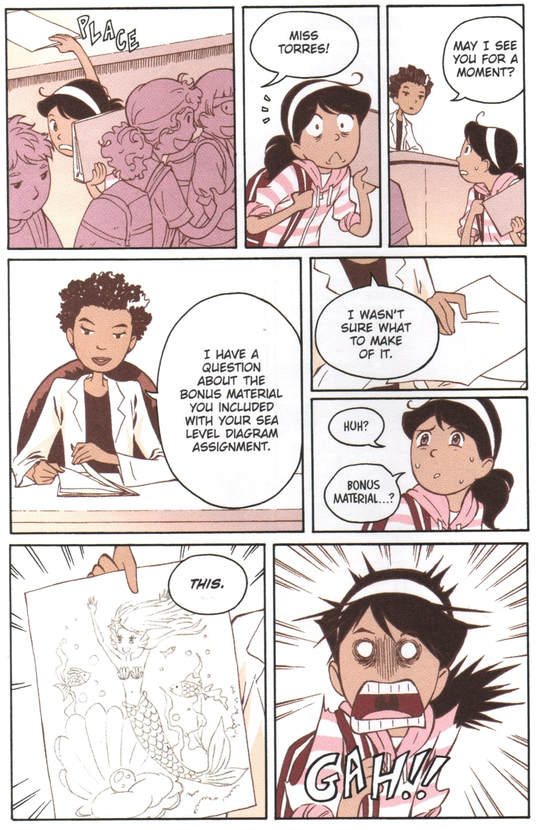

Awkward. By Svetlana Chmakova. Yen Press, 2015. ISBN 978-0316381307. 224 pages, $11.00. I missed this one when it came out in 2015, and missed its sequel, Brave, when it dropped in spring 2017—so I have some catching up to do. Awkward, now the first book in the growing Berrybrook Middle School series, is a middle-grade graphic novel about warring school cliques: art nerds versus science nerds. More particularly, it’s about the (of course) awkward relationship between Peppi, an art girl, and Jaime, a science boy, a relationship that promises to bridge the divide between those two competing nerddoms. The book cannily targets its intended age group with comically overwrought depictions of social anxiety, tentative friendships, and rivalries that seem epic to those involved even though they might seem minor to anyone else. It’s an eager, infectious riff on school life manga, from a cartoonist, Svetlana Chmakova, who prior to Awkward had specialized in OEL manga, with a fairly long list of titles from Yen (Nightschool, Witch & Wizard) and TOKYOPOP (Dramacon). Like Vera Brosgol, Chmakova is a Russian immigré with an animation background, but her career path has been different. She has described herself as a “manga author,” and Awkward takes a very manga-like pleasure in the absurdities of school life. Yet her manga influences now seem to be retreating, or quieting down, in favor of a Raina Telgemeier-like aesthetic of clarity and containment. Granted, shōjo manga still looms large in Chmakova’s style, which favors outsize expressions and exaggerated, super-deformed bursts of feeling—but she damps down the manga influence here by working through a gridlike page-and-panel aesthetic that follows the reigning style of US children’s graphic novels. Bleeds and diagonals are few, progress tends to be more horizontal than vertical, most pages are tidily contained within a white frame, and the effects lettering is fairly subtle and contained (with one terrific exception that you can find for yourself). In other words, Awkward, even as it leans hard on strong feelings and comic timing, dials down the manga elements and the intensity, instead aiming for a studied clarity. We are definitely in Raina territory here (Brosgol’s latest, Be Prepared, also goes there). Like much school life manga, Awkward stitches together the everyday and the outrageous, with cartoonishly exaggerated teachers, a shadowy, unseen principal who seems to hold the power of life and death, and petty disputes that flare up into high drama. The premise of art versus science, and the inevitable realization that the two can go together (cue the da Vinci), are not very fresh, and in general Awkward makes mountains of molehills, inflating minor screwups into soul-wrenching dilemmas. Further, we learn little about the protagonist Peppi’s home life or tics, apart from her love of drawing and her desire to stay as quiet and invisible at her new school as she possibly can. Scenes outside of school are set up to show Peppi the unexpected depths of her schoolmates; she herself doesn’t seem to have any. Awkward is not a very complex story, and Peppi’s eventual move from diffidence to action is foreordained. The character who exhibits the most depth—a go-getter classmate whose infectious, take-charge enthusiasm hides a troubled home life—gives the story a welcome dose of gravitas, but then disappears altogether. Her fate remains a dangling loose end as Chmakova rushes to the denouement. Awkward, then, is not a story that bears much critical thinking. However, it is delightfully rendered, and its unpredictable mix of comic hyperbole and genuine angst makes me want to read the sequels. Berrybrook Middle has the potential to be a great fictional school and story engine, and Chmakova, working at the crossroads of multiple traditions, has found a distinct style and energy of her own. Time for me to go read Brave.

The Kurdles. By Robert Goodin. Fantagraphics, 2015. ISBN 978-1606998328. Hardcover, 60 pages, $24.99. A teddy bear gets lost, or discarded, by a child—that's how The Kurdles begins. Will she, Sally Bear, be reunited with "her" child"? The plot feints in that direction: a common story problem for child-centered, toys-come-to-life tales. Think Toy Story, and the nostalgia those films invoke: they're all about a kidcentric microcosm in which toys, though sentient, depend on the love of a child to give their life meaning. But The Kurdles doesn't end up telling that kind of story; instead it pulls a narrative bait-and-switch and becomes a sort of anti-Toy Story, one in which no Andy or Christopher Robin is needed to confer life or purpose on the lost teddy. Sally finds herself in Kurdleton, a woodland retreat, in the company of other critters: a land-going pentapus (think octopus with just five limbs), a unicorn in a tee shirt and jeans, and a scarecrow that evokes Baum's Oz (with perhaps a touch of Johnny Gruelle's Raggedy Andy too). This klatch of strange beasts also recalls, for me, Tove Jansson's Moominland, or Enid Blyton's Faraway Tree series. There's that same sense of utopian, slightly anarchic domestic community, of a little world apart from our own with its own matter-of-fact logic (or no governing logic at all). This is home to The Kurdles, and where the story wants to stay. With The Kurdles, then, cartoonist Robert Goodin has fashioned a fantasy world that owes a great deal to the history of children's books. Oddly, though, the book seems out of step with almost anyone's idea of a children's graphic novel today. The Kurdles does kids' comics the way, say, Gilbert Hernandez and co. did with Measles (1998-2001), or the way Jordan Crane did with The Clouds Above (2005)—that is, eccentrically, with seemingly no regard for the conventional wisdom about what today's children need or want. I suspect that's part of the reason why I like The Kurdles so much. Certainly I like this kind of idiosyncratic world-building in comics, regardless of intended audience. I expect that The Kurdles' best audience will be comics-lovers with a feel for the medium's history and an appetite for the upending of traditional story motifs. Me, I like it for the quirks and for the way it refuses to make sense. The book's opening depicts an argument between a human mother and child, as seen from a distance by a teddy bear. We don't yet know that the bear is Sally, or that she's alive: Sally's autonomous life is revealed only gradually, slyly, in the pages that follow, after she is parted from this human family. (The sequence in which she finally transitions from inert doll to living, moving creature is so delicious that I'm not going to show it here.) It takes even longer to reveal Sally's capacity for speech—which we realize about the same time as her capacity for self-defense, even violent resistance. What brings Sally fully to life is her arrival in Kurdleton, and the appearance of Kurdleton's other bizarre residents: What follows is a shaggy dog story in which a sickly house (the sum total of living quarters in Kurdleton) becomes anthropomorphic and then, as if delirious with flu, begins to sing sea shanties as if it were a drunken sailor. Yes, you read that right. The other denizens of Kurdleton set out to find a cure, but I'll say no more. Suffice to say that the Kurdles have no origin stories, no explanations for why they live in this place, nor any backstory that anyone feels obliged to ask about. Only Sally, of all the characters, has the rudiments of an "arc" (and even hers gets rerouted). What's more, the Kurdles don't have the familial structure of Jansson's Moomins, or the love of a human child, à la Milne's critters in the Hundred Acre Wood, to bring them together. They're just weird, and live in a weird place, where their essential weirdness needs no excuse. That's The Kurdles. The Kurdles is also eccentric visually. Lushly drawn and watercolored, it's organic, i.e. emphatically pre-digital, in look, with a fully realized, woodsy environment. Boldly brushed contours coexist with dense hatching, and the art is texture-mad. Color-wise, Goodin's pages depart from the Photoshop norm of most children's graphic books, and I found myself looking for the rough edges where linework and watercolor met (though Goodin is so crisp that I hardly ever found them). The work is old-fashioned and sumptuous, illustrative and humanly accessible to these middle-age eyes. Far from the clear-line, flat-color style so redolent of children's comics (the bright Colorforms look that bridges everything from Hergé to Gene Yang), The Kurdles is beautifully scruffy, or scruffily beautiful. It's as if Goodin, whose work I know mainly from TV animation and his erstwhile Robot Publishing venture, is determined to make The Kurdles a space of retreat from all of his other doings. The Kurdles is blithe, blunt, and unsentimental, sometimes startling, often deadpan-hilarious: a world and logic unto itself. I dig it. I do worry, though, about the commercial prospects for work like this, i.e. work that carries with it a wealth of history and memory but hails from outside of the children's publishing mainstream. This is the sort of work that has flourished fitfully here and there under the aegis of the direct market and within a small-press, underground aesthetic (I think for example of Neil the Horse, c. 1983-88, by Katherine Collins, formerly Arn Saba). Fantagraphics has announced a Kurdles Adventure Magazine for this summer, and reading more Kurdles would do me good, so I can only hope. This is too weird and wonderful a world to lie fallow. Fantagraphics provided a review copy of this book.

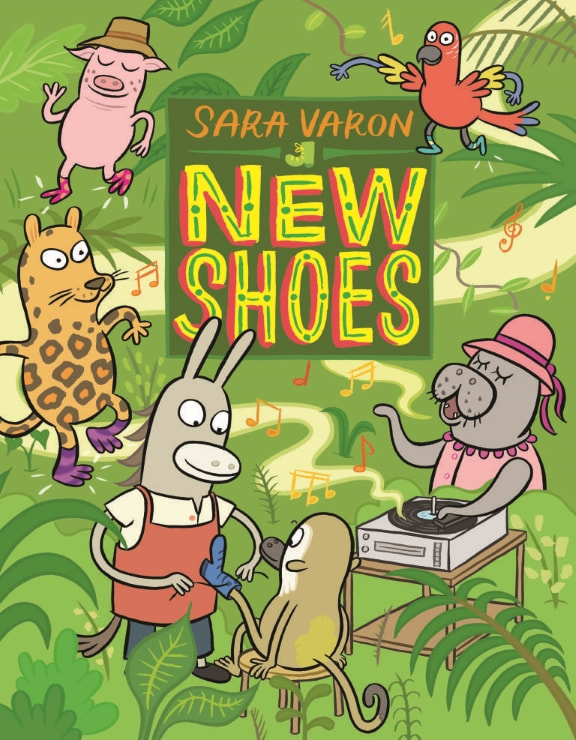

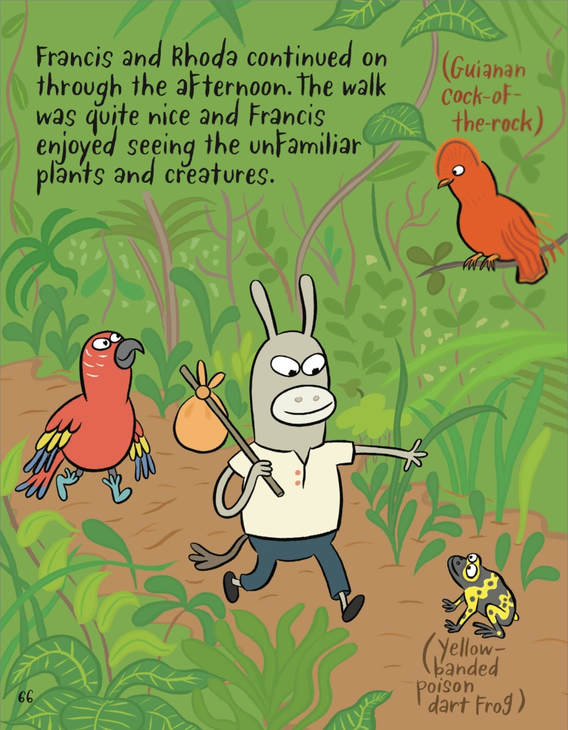

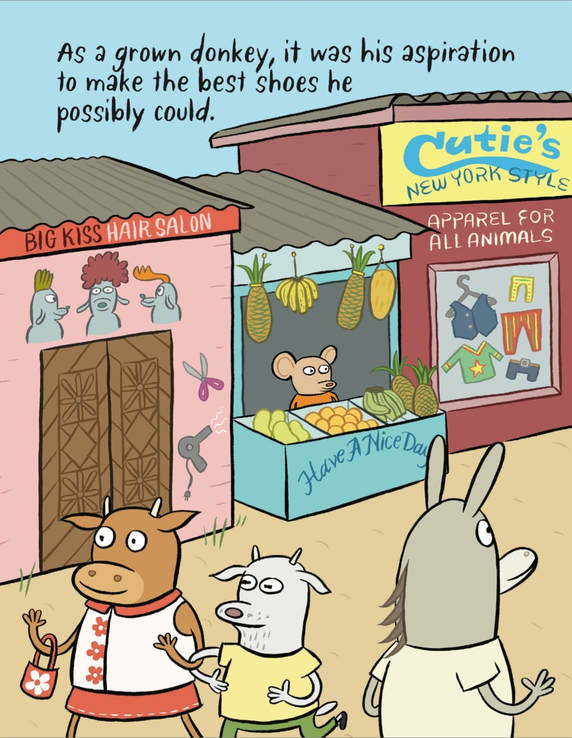

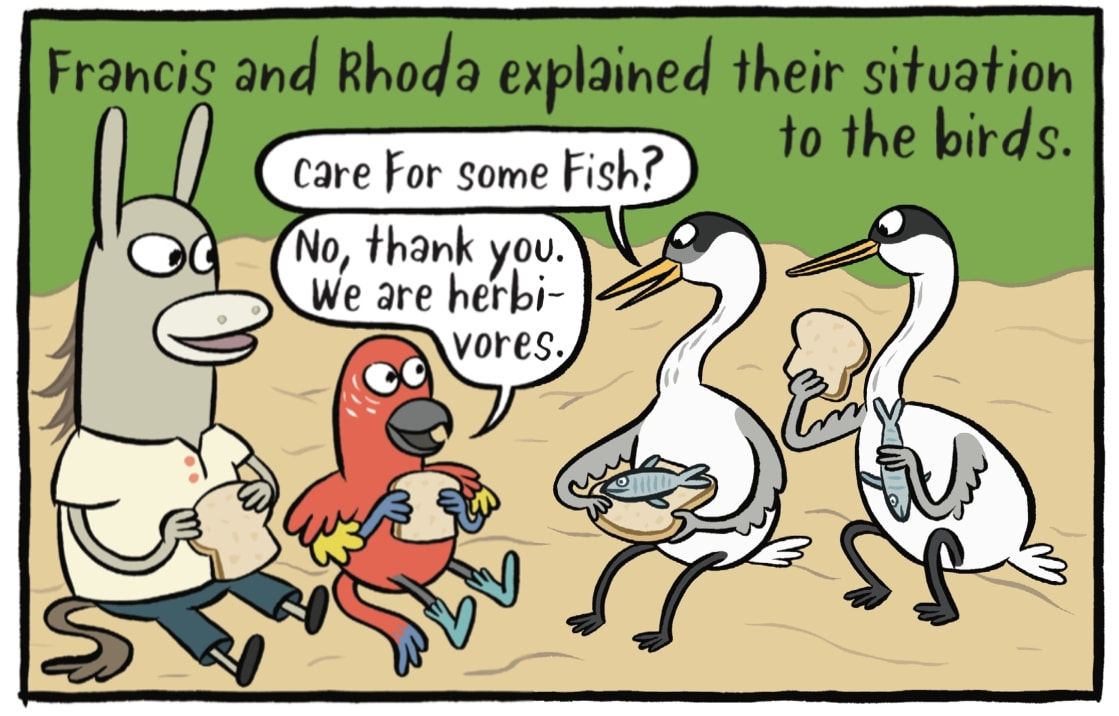

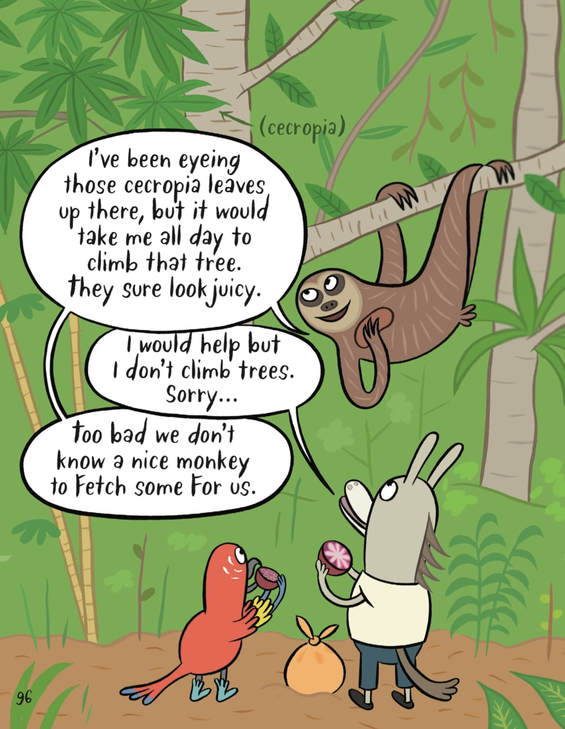

New Shoes. By Sara Varon. First Second Books, March 2018. Hardcover, 208 pages. ISBN 978-1596439207. $17.99. Book design by Danielle Ceccolini and Sara Varon. New Shoes, a genial, unlikely fable, follows a cobbler named Francis who wants more than anything to make the perfect pair of shoes for his favorite singer, a pop star who is coming to his town. To that end, he hopes to enlist his traveling friend, Nigel, to secure the needed supplies—but Nigel, it turns out, is missing. So Francis, aided by another friend, Rhoda, embarks on a quest to get the supplies himself (and find Nigel). The thing is, Francis is a donkey, Nigel is a squirrel monkey, Rhoda is a macaw, and the singer, Miss Manatee, is just that. New Shoes is an animal fable—and not in the purely metaphorical sense of, say, Spiegelman’s Maus, in which human characters wear mask-like animal faces. No, these animals are meant to be animals, even though they’re anthromorphized. Francis, despite wearing clothes and shoes, is emphatically a donkey. Rhoda is a bird (she flies). And so on. In this world, varied animalness is the point. Once again, Sara Varon (Bake Sale, Robot Dreams, Chicken and Cat, Sweaterweather, etc.) has created a funny animal comic that is, yes, funny, but more than that. New Shoes takes place in a tropical world inspired by Guyana. Francis and Rhoda’s quest entails journeying into “the jungle,” i.e. equatorial rainforest, and the book lovingly details Guyanese flora and fauna. Varon gives labels for myriad critters: black curassow, golden-handed tamarin, three-toed sloth, and so on. Ditto for plants: cecropia, philodendron, bromeliad. In other words, the book packs in a lot of zoological and botanical information. More than that, New Shoes implicitly reflects Guyanese culture: an Anglophone Caribbean mix with a complex colonial history and diverse population. Signs in Francis’s village are in English, village buildings are small, colorful, and individual, and Varon’s myriad animal types may stand in, allegorically, for Guyana’s mingling of East Indian, African, Amerindian, and other peoples. Miss Manatee, “the River Queen,” is a calypso singer, and listening to calypso on phonograph records seems to be a cultural constant (record players are an important prop throughout). Varon’s version of Guyana is perhaps utopian but based on direct experience: her husband, John Douglas, former boxer and Olympian (1996), is from Guyana, and her visits there, specifically to the town of Linden, seem to have shaped if not inspired the whole book. The specific cultural and geographical influences of Guyana make New Shoes stand out among Varon’s animal tales—and the characters’ varied animalness implicitly celebrates Guyanese diversity. Thus New Shoes espouses cooperation and harmony-in-difference without dealing explicitly with race, ethnicity, or postcoloniality. This charming fable rests on a complex, if largely implied, cultural foundation. I was struck by the book’s depiction of labor and economy. Even as it extols friendship and community, New Shoes focuses on acts of exchange: goods for goods, goods for work, and work for work. Yet money plays no role; barter and trade are everything. Rhoda agrees to help Francis on his quest in return for a pair of shoes. Francis offers bread to passing herons, who in return counsel him to seek help from some capybara. Later, Francis trades bread to the capybara and some river otters in return for swimming lessons and advice. Later still, he settles a debt with Harriet, a jaguar, by offering her his guidebook to rainforest animals, and then the two make a further exchange: some of Harriet’s plants, and advice on how to take care of them, in return for a pair of Francis’s shoes. While the book also depicts acts of spontaneous, uncompensated kindness—say, a neighbor helping a neighbor—much of its action involves establishing reciprocity and trust through barter. Tellingly, these exchanges are not merely economic but also build goodwill and community. If some characters seem altruistic, others, by contrast, appear self-interested—yet all of them come together civilly through the act of trading. What’s more, the worst offense in the book turns out to be thievery, when a character decides to take something for nothing rather than making an honest trade. Varon’s utopia, then, is not without practical considerations of trade and work, but couches those in terms of communal ethos rather than capital. New Shoes could spark some fascinating exchanges with young readers about use value, exchange value, and perhaps even alternatives to commodity capitalism! Varon’s work has a distinctive charm. Her stories, as New Shoes amply demonstrates, tend to be about not only moving the plot forward but also taking an interest in the world, imparting information about geography, culture, or beloved pastimes. They represent the work and the pleasure of learning. At the same time, Varon uses animals and other “nonhuman” characters to convey feelings of friendship, love, and loss (most piercingly, I think, in her breakthrough book Robot Dreams). Along the way, she scatters moments of droll, deadpan humor: Varon's telltale graphic style is very readable. Her character designs are distinct and unmistakable; every character looks different from every other one (and I can see some influences she has cited, including Jay Ward and William Steig). The figures are clean and shadowless, yet outlined by robust brush-inking. Her bright, unshaded pages boast discrete forms and solid, eye-popping colors, yet also a complex mixing of hues (as in the varied shades of green that make up New Shoes’s rainforest). Inked on Bristol board but then colored in Photoshop (as is Varon's SOP), New Shoes happily blends old-school and digital methods, combining springy linework with subtle coloring. Layout-wise, Varon alternates between framed and unframed images, favoring big, open spreads and full bleeds. Often, single images take up a page or spread; alternately, Varon may go for a page of two or three (or, very rarely, four) panels. Clarity and momentum are all, and New Shoes fairly carries the reader along. Sara Varon has become one of First Second’s signature authors. I had the privilege of interviewing her, back in 2009, at the International Comic Arts Forum in Chicago, and it has been a pleasure to see more and more of her work—work that explores friendship and community for the benefit of young and old readers alike. New Shoes charmed me right off, but keeps growing in my estimation as I think about it—another delightful, subtle, low-key triumph. First Second provided a review copy of this book.

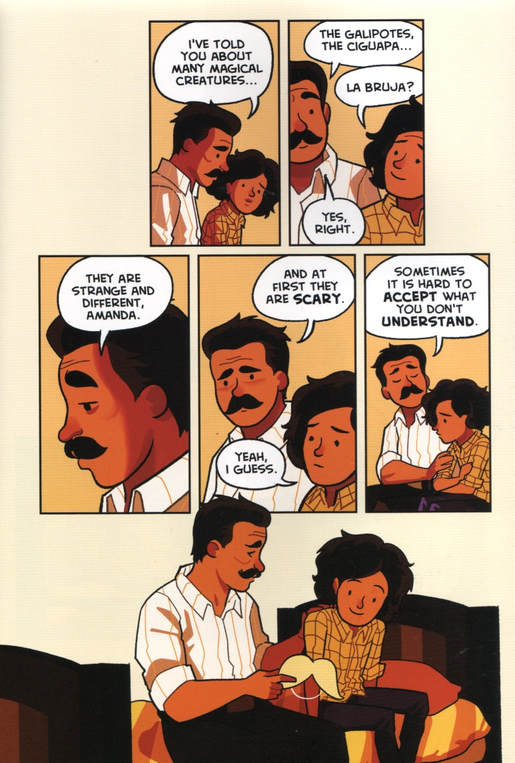

The Cardboard Kingdom. By Chad Sell, with Vid Alliger, Manuel Betancourt, Michael Cole, David Demeo, Jay Fuller, Cloud Jacobs, Kris Moore, Molly Muldoon, Barbara Perez Marquez, and Katie Schenkel. Alfred A. Knopf/Random House Children’s Books, June 2018. ISBN 978-1524719371. Hardcover, 288 pages, $20.99. The Cardboard Kingdom celebrates community and in fact is the work of a community: a team made up of cartoonist and creator Chad Sell and ten co-writers, referred to by the publisher as “new and diverse authors” (one of whom, Kris Moore, sadly seems to have passed away). An impressive collaborative feat, it depicts an idealized neighborhood of kids who also collaborate, turning their everyday lives into, basically, a nonstop live-action roleplaying game. A paean to shared creative play—essentially, the book is about kids as cosplayers, crafters, and friends—it must also have been a playful, if complicated, project. Happily, everything clicks. The book works as an anthology of short stories and vignettes, from about five to thirty-plus pages in length, but more powerfully as a novel, which, though episodic, designedly builds to a big and satisfying finish. Sell enlisted each author to write a story or two, and then apparently brought them together to cook up the boffo finale. Reading it straight through, it’s almost seamless; the novel builds its neighborhood carefully, gradually introducing new characters into its busy communal scenes. Though the publisher says The Cardboard Kingdom is about “sixteen kids,” I counted nineteen distinct, recurring child characters in the novel, some identified only by their roleplaying names, some known by more than one name. There’s a lot of juggling going on, but never to the point of distraction. The publisher also says that the book depicts “adolescent identity-searching and emotional growth”—yet it certainly isn’t YA fiction. My sense is that The Cardboard Kingdom is emphatically a middle-grade novel, aiming for upper elementary to perhaps middle school age. While its large cast, complex rigging, and lively and dynamic pages say “middle-grade” to me (not younger), its eager, almost ingratiating cartoon style reminds me of Pixar—say, Inside Out, with its mix of emotional gravity and toylike cuteness. Certainly the book depicts identity-searching and emotional growth; however, its bright cartooning, winsome children, and almost Peanuts-like sense of suburbia (not wholly idyllic like Schulz’s but still reassuringly safe) seem pre-adolescent in tone. Its let’s-pretend and DIY ethos brings back some early memories of my own. I mention this not because I’m concerned about age levels (KinderComics doesn’t usually focus on leveling) but because I’m interested in The Cardboard Kingdom’s treatment of identity, which I consider bold for a middle-grade novel. If graphically the book suggests years of reading Peanuts and Tintin, its imagined neighborhood has a utopian queer- and trans-positive vibe that would make it a good companion to, say, Alex Gino’s groundbreaking George (also a middle-grade fiction). Among the book’s young role-players are several who defy or ignore gender norms. In fact the first story, “The Sorceress,” written with Jay Fuller, introduces a cross-dressing pair: the titular Sorceress, soon shown to be (ostensibly) a boy but only much later identified as “Jack,” and his neighbor, a seeming girl who refuses the princess role and becomes The Knight (I don’t think she ever gets another name). Reportedly, this story was the kernel or inspiration for the whole book. There’s more: one character, Sophie, defies expectations of sweet girlishness and becomes a rampaging, Hulk-like bruiser she calls The Big Banshee; another, Amanda, a self-styled Mad Scientist, worries her father by wearing a mustache. Meanwhile, the relationship between Miguel the Rogue and Nate the Prince hints at a young gay crush. The Cardboard Kingdom, in fact, resists conventional gender and sexual roles throughout. For all that, it’s a story about kids who like to imagine combat: big, frenzied dust-ups between heroes and villains. Reading it, I was more than once reminded of an Avengers movie. If the drawing style and solid, bright colors follow a clear-line aesthetic, recalling the moral and ideological sureties of so many children’s comics, then Jack Kirby is surely a reference point too, from the Big Banshee’s unabashed monstrousness (more cheerful than tragic here) to the outrageous costuming, replete with spiky cardboard headgear that would do Cate Blanchett proud. The book taps the same vein of explosive fantasy that superhero comics do, but with more charm than most. The neighborhood kids of The Cardboard Kingdom, though they never really hurt one another, like to run around and fight; Sell and company are unafraid of children’s capacity to play at physical conflict and violence. Further, many of the kids like to be “bad guys” as well as “good,” and the book gleefully mines that tendency for humor. There’s a disarming mixture of sweetness and brutal imaginings in the book, though it all comes out seeming like harmless fun. Sell and his collaborators have a feel for the reckless, revved-up fantasy lives of young kids hanging out together--I appreciate that. And no adult ever dictates the terms of, or reins in, what the kids are fantasizing about. The book presents an entirely child-driven and child-centered world of cooperative, if pugnacious, play. In short, it’s feisty as well as sweet. Behind its bright, cheery surface, then, The Cardboard Kingdom is structurally tricky and thematically gutsy. On the critical side, I would say that some of its component stories resolve too quickly; the book runs the risk of being too neat, because its nested structure and sheer number of characters demand fast pacing, even when dealing with hard matters of identity and parent-child tension. Problems are invoked and solved with speed. In that sense, it’s, again, utopian. Also, the book makes some obvious, even heavy-handed, didactic moves, though in the direction of adult chaperones rather than child readers. Its sharpest lessons will likely be ones of forbearance and acceptance aimed at concerned parents whose children are behaving, well, unexpectedly. The best examples of parenting in The Cardboard Kingdom involve suspending or tempering judgment, i.e. being brave about children’s imaginative self-fashioning (would that all anxious parents course-corrected as readily as those in the book). But, most of all, it’s the book’s wise embrace of childhood play that makes The Cardboard Kingdom a brave and interesting graphic novel, one I highly recommend. Random House provided a review copy of this book.

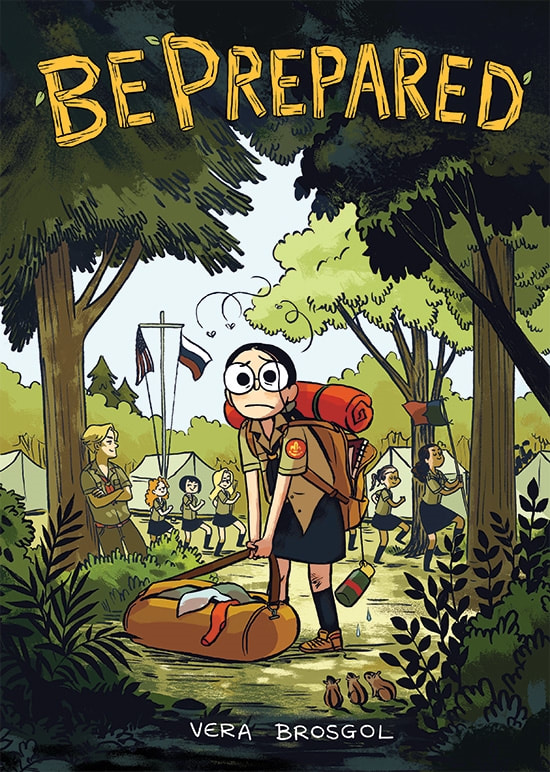

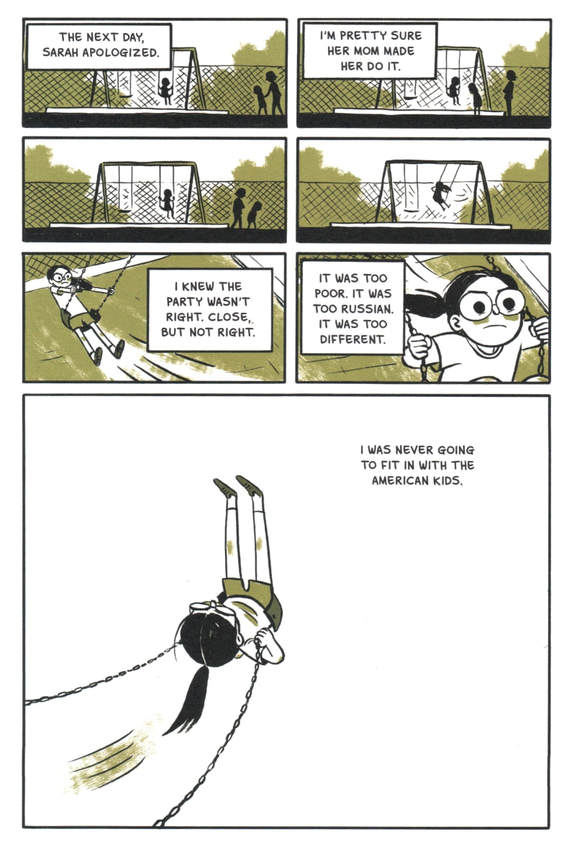

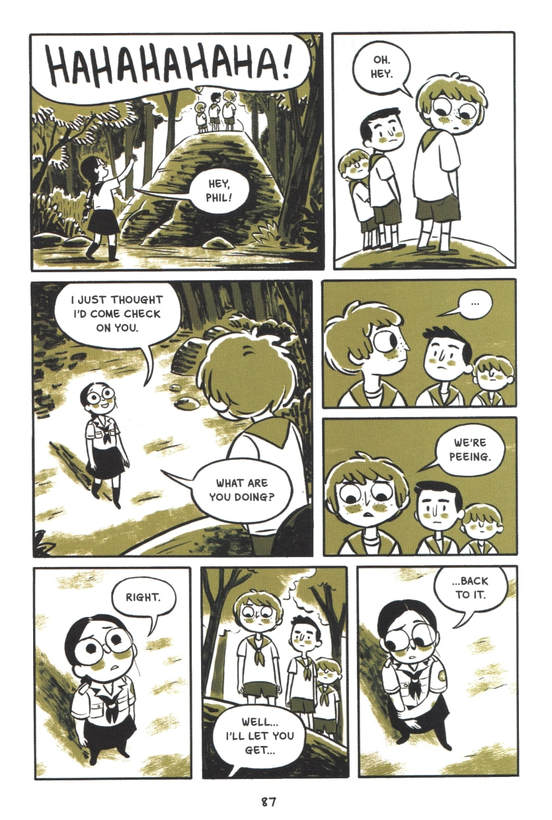

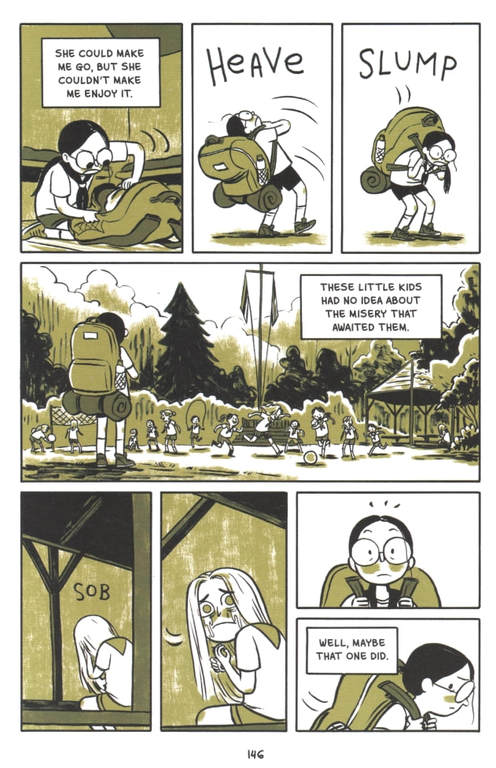

Be Prepared. By Vera Brosgol. Color by Alec Longstreth. First Second Books, April 2018. 256 pages. Hardcover, ISBN 978-1626724440, $22.99. Softcover, ISBN 978-1626724457, $12.99. Book design by Danielle Ceccolini and Rob Steen. About seven years ago, animator and storyboard artist Vera Brosgol entered the world of graphic novels with a walloping big success: Anya's Ghost, a supernatural fantasy rooted in the experience of being a Russian immigrant girl struggling to fit into American life. Brosgol knew this struggle firsthand, having moved from Russia to the US at age five. Anya's Ghost changed Brosgol's life: rapturously reviewed, the book went on to win Eisner, Harvey, and Cybil Awards. Its theme of trying to disavow one's cultural roots resonated with Gene Luen Yang's epochal American Born Chinese, which had been published some five years earlier (both were published by First Second). The two books drew upon popular genres—myth fantasy, superheroes, ghost stories—to fashion nervy fables of complex and ambivalent identity. In that sense, Anya's Ghost appears to have struck a nerve. Now Brosgol, having also authored a Caldecott Honored picture book (2016's Leave Me Alone!), has just released her second graphic novel: the autobiographical Be Prepared, in which a nine-year-old Vera, again a self-conscious Russian immigré, goes to summer camp. Be Prepared is in the same vein of comic memoir as Raina Telgemeier's hugely popular Smile (2010) and Sisters (2014), and indeed the book is being promoted in that light (and has been blurbed by Telgemeier herself). Thematically, however, it pairs with Anya's Ghost, as it mines Brosgol's experience as an immigrant to tell another story of the struggle for identity. This time, though, the story happens in the company of many other Russian kids, in the context of a Russian immersion camp with Orthodox roots. From this intriguingly specific setting, Be Prepared builds a book that turns out to be, tonally, quite different from Anya's Ghost, yet is just as wonderful. Be Prepared begins with, once again, the discomfort, or even humiliation, of being a markedly Russian girl in a suburban American world dominated by unmarked middle-class Whiteness. Yet, whereas Anya's Ghost centers on a somewhat sullen and alienated adolescent, and thus tacks in the direction of Young Adult fiction, Be Prepared's Vera is naive, hopeful, and intimidated by teens. Yet she is worldly-wise enough to know that she sticks out like a sore thumb, that she is too ethnic, "too different," to fit easily into her town and school in Upstate New York. Indeed Vera is painfully aware of being "too poor" and "too Russian" to blend in with her schoolmates. However, whereas Brosgol's Anya seemed determined to shed her Russianness, Vera thrills to the prospect of attending an all-Russian camp in the New England woods. Most of her schoolmates go away to camp every summer, leaving Vera adrift and bored, but when she learns of a camp where "everyone would be Russian like me," she dares to hope that it will ease the pain of being different. "I had to go," she says. "I had to go." Vera and her little brother Phil do go, and here is where Be Prepared takes off, as it conjures the distinctive setting of a Russian scouting camp, dotted with Russian signage and Orthodox icons. The setting appears to be (guesswork here) based on a real-life camp run by the Organization of Russian Young Pathfinders (Организация Российских Юных Разведчиков, or ORYuR) or some similar Russian Scouting in Exile group. It's all about being Russian, all the time. Camp songs are sung in Russian; Russian speech (a constant) is represented by English within brackets; and each week the boys and girls compete in a capture-the-flag contest called napadenya (attack). The problem is, camp sucks. Vera's hopes of fitting in are dashed: she is placed with older girls who patronize her, her Russian is too tentative, and roughing it freaks her out. Too late: she is committed, and has to stay. Thence comes much of the book's poignancy and humor. I appreciate the frankness, and sometimes rawness, of Brosgol's humor. As she did in Anya's Ghost, here again she tests what a young reader's book can get away with. The young campers of Be Prepared are emphatically people with bodies, and much of the book's comedy stems from putting those bodies under duress, as happens when you go camping. Bites, stings, toileting, and adolescent growing pains are all played for laughs, and many of the gags involve visits to the dreaded latrine. There's some pain behind the laughs. Brosgol's humor has a salty matter-of-factness that will likely ring true for just about anyone who's ever been to summer camp, as in this sequence where Vera pays her brother a rare visit: Or this mortifying moment between Vera and her two tent-mates: There is more to Be Prepared than these moments of rough humor and embarrassment. There's testing, growth, and self-recognition. There's struggle and loneliness, but ultimately affirmation (though thankfully no platitudes). And, man oh man, is there great cartooning. Be Prepared is a delight because Brosgol is an ace artist with a gift for designing characters, pacing stories, and building pages. The characters, as one might expect of a skilled animator, are clearly tagged, i.e. graphically distinct. Young Vera herself, moonfaced, with coke-bottle glasses and big, dark dots for eyes, is unmistakable: a live antenna of a character, veering from joy to misery, anticipation to disappointment. Brosgol cartoons her (that is to say herself) with comic brio, ruthless insight, and, yes, empathy. Other characters are vivid types, from Vera's teenage tent-mates, both named Sasha, to the cocky alpha male they compete over, to Vera's camp counselor, at first harried and remote, later sympathetic. Brosgol steers these characters and more through shifting moods, reversals, sometimes betrayals, and oh so many moments of cringing social awkwardness. Further, Brosgol's way with a page, her rhythmic sense of how to make each page build to a payoff, gag, shock, or suspenseful breath, is exhilarating. Her dynamically gridded pages, avoiding tedium but seldom grandstanding, serve the elastic rhythms of the storytelling, and wow does the story move. Though her methods are entirely traditional and convention-bound, Brosgol's sheer fluency is something to behold. Be Prepared is visually masterful, from exacting body language, to precisely observed physical business (camping, hiking, sneaking around), to the rare moments of, whew, calm. Much credit must go to the gorgeously worked surfaces of the pages, completed by the sumptuous coloring of Alec Longstreth, who works wonders with a riotous mix of greens (my scans, here, are too dull to do his work justice). For a strictly "two-color" book, green and black, Be Prepared is replete and ravishing, an opulent outlay of textures. Be Prepared is beautiful, gutsy, and funny. Granted, it does not have the Gothic horror of Anya's Ghost, and does not resonate quite so unnervingly. Rather, it's a breeze of a book, a charming, vivid comedy. Yet a closer look reveals moments of trouble and complexity that, as usual for Brosgol, are not tidily resolved but instead allowed to hang, unfinished and provoking. There are still doses of painful honesty behind the bright, emphatic delivery—and the ending somewhat short-circuits the expected lessons of growth and acceptance, to my delight. If Be Prepared isn't nominated for several awards next year, I'll eat my hat. Need I say that it comes highly recommended?

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed