|

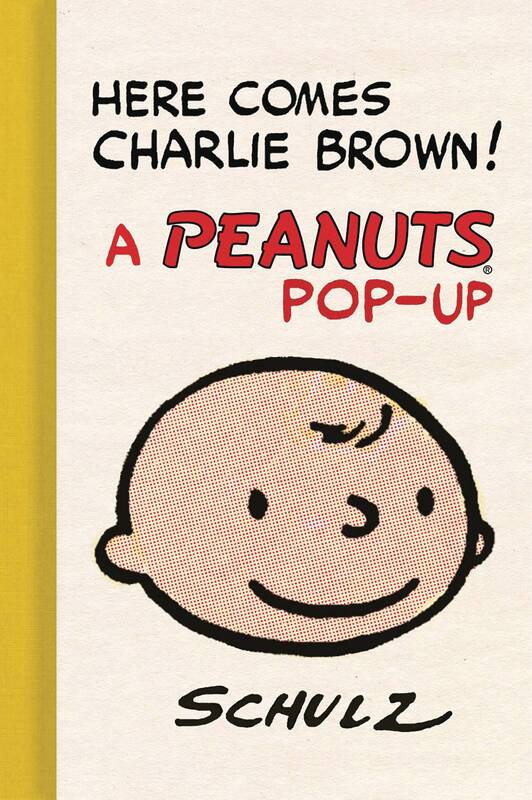

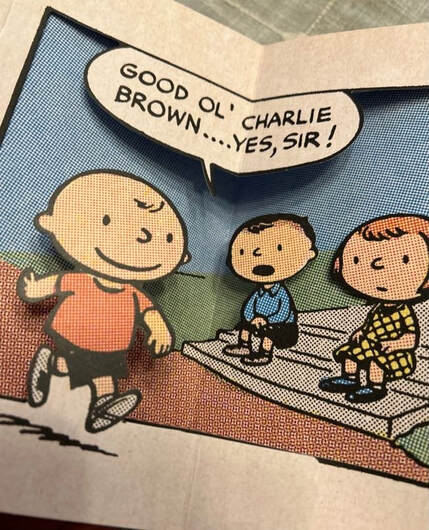

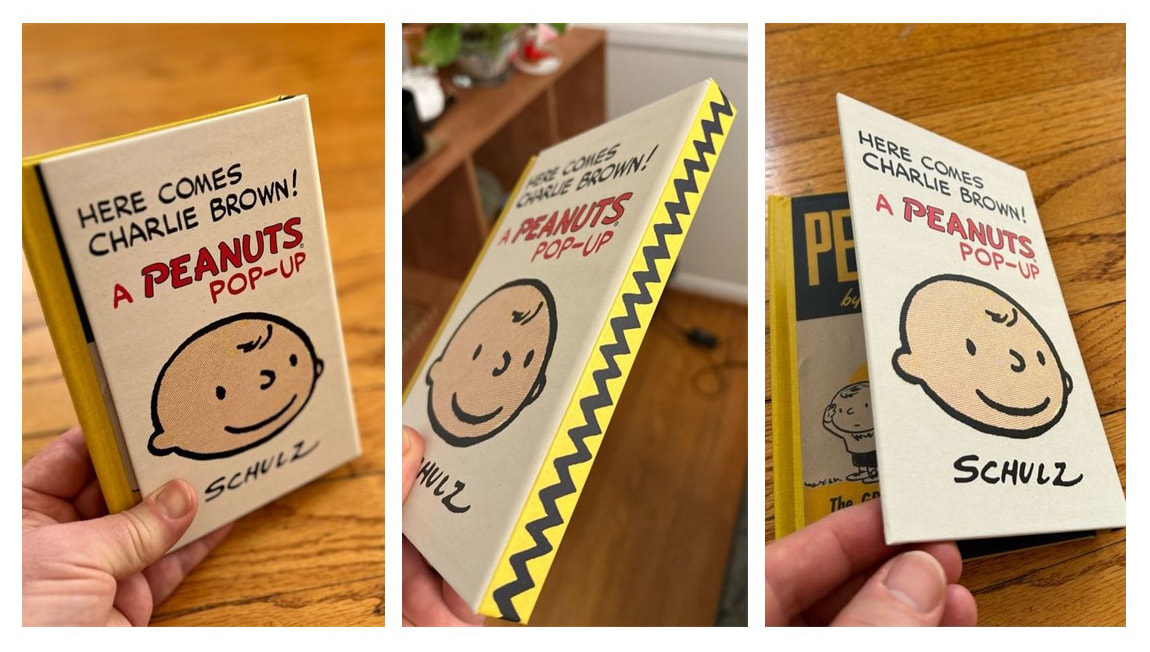

Here Comes Charlie Brown! A Peanuts Pop-Up. By Charles M. Schulz. Paper engineering, coloring, and afterword by Gene Kannenberg, Jr.; design by Shawn Dahl; front cover design by Chip Kidd. Abrams ComicArts, ISBN 978-1419757785, March 2024. US$16.99. 12 pages, hardcover. There are gift books, and then there are gift books. If there is a Peanuts fan in your life, this is for them, full stop. It's definitely for me! This is hardly an objective review. For one thing, I'm a gushing fan of vintage Peanuts stuff. For another, Here Comes Charlie Brown! was brainstormed and engineered by my colleague Gene Kannenberg, Jr., one of my oldest and dearest friends, with whom I've shared countless hours geeking out over comics and bookness. Gene helped me get through grad school with his sympathy and brilliance, and he just keeps on giving! So, I won't pretend to be disinterested this time. Here Comes Charlie Brown! is an ingeniously engineered pop-up book consisting of, mostly, the first-ever Peanuts strip, originally published on October 2, 1950: the beginning of Charles Schulz's famed half-century run. So, it's basically a deluxe reformatting of a single four-panel comic strip. Physically, it resembles a chunky board book, and has just six openings (the last one devoted to a revealing and insightful afterword). Gene K. has colored the originally black-and-white strip, in a subtle, slowly darkening way that matches its acerbic punchline. The coloring, based on Ben-Day dots, feels vintage — as Gene notes, a digital equivalent of mid-20th century comics coloring. What really gets me is the layering of the images: each pop-up opening has three layers, or depths, and Gene shifts the layering with every panel, to, as he says, "amplify" the power of Schulz's original. This effect seemed subtle at first, but becomes more and more forceful with each re-reading. It's super-smart and very much in tune with the complex tone of Schulz's humor. All this may sounds simple — a book re-presenting a single short strip — and it's true that my first reading of the whole book took only a few minutes. Yet Here Comes Charlie Brown! is one of those books that makes you self-conscious about being a book user, and even about the whole idea of bookness. It intensifies the comic strip reading experience while making me think about how books are put together. The overall design is by Shawn Dahl (who often designs for Abrams and has done several books with Mutts creator Patrick McDonnell), and it's striking. The book's heavy cover actually wraps around and encloses the whole thing, making it feel less like a conventional book than a gift box; that is, the back cover reaches around to the front, creating a front flap that, counter-intuitively, you have to open from left to right. I cannot describe it well, but perhaps some pictures will help: This has the effect of creating a sturdy shell for the finely wrought contents inside, strengthening what could otherwise seem delicate. The hand feel of this chunky, pocket-sized object is exquisite. What's more, the visual design of the book is spot-on, with a front cover that consists almost entirely of elements lifted from the original strip. Even Schulz's signature seems to have been repurposed from that strip. So, there are a number of visual rhymes and reinforcements in the total package. Everything resonates. It's a delightful exercise in pure bookness. Here Comes Charlie Brown! is more than a decorative novelty. It's an interpretive act: a sensitive reading and reframing of Schulz's original. I can't stop paging through it! I dearly hope it will be the first of a series.

1 Comment

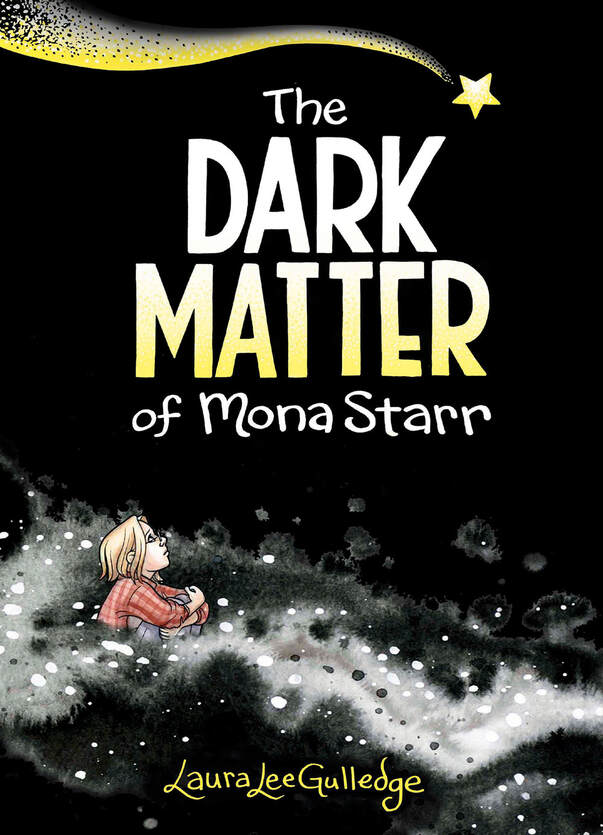

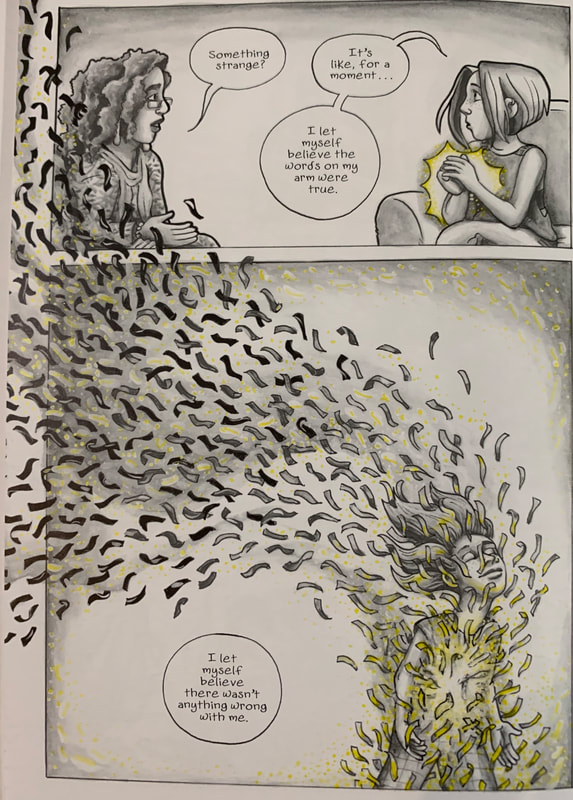

The Dark Matter of Mona Starr. By Laura Lee Gulledge. Amulet Books/ABRAMS, 2020. ISBN 978-1419742002, $US14.99. 192 pages. In this semi-autobiographical novel, Mona, a high-schooler and artist who suffers from depression, undertakes a self-study to better understand her needs and triggers and fashion a "self-care plan." Though a loner by temperament, she learns to think outside of herself and recognize loving relationships and creative collaboration as important resources in her life. With the help of her counselor, parents, and friends, Mona chooses an ethic of community and participation, sharing her aesthetic gifts and inspiring others to do the same. Looking beyond herself, even as she honors her own needs, enables her to engage the world on different terms and, to some degree, counteract her depression. The novel climaxes with a community art project in which Mona and her self-styled "Artners," Aishah and Hailey, invite many of their fellow high-schoolers to collaborate in a spirit of loving community. The story's keynotes are self-love, self-advocacy, and willful optimism, and its last word (literally) is hope. Like Ellen Forney's celebrated memoir Marbles, this novel hovers between raw personal storytelling and hortatory self-help, with chapter headers that give emphatic advice, such as Turn emotion into action and Break your cycles. Author Gulledge shares her own self-care plan in the back pages, and her notes confirm that Mona Starr is indeed based on her. Artistically, the book is wildly expressive; the pages brim with visual metaphors of depression and elation, self-isolation and self-release, artistic engagement and pure joy. Depression, Mona's so-called dark matter (her mom is an astrophysicist), appears as swirling black clouds, faceless anthropomorphic demons, dark waters, black flames, and gripping hands. Moments of self-realization and delight are accompanied by stars and streaks of bright yellow: the one spot color in Gulledge's otherwise black-and-white, or rather grayscale, aesthetic. Mental landscapes — vast oceans, deep, dark wells, and the swirling cosmos — convey Mona's ever-shifting inner state. Consensus "reality" is perfused with expressionistic symbolism, and many pages leave behind real-world settings altogether. The sheer profusion of visual symbols reminds me of, say, Iasmin Omar Ata's Mis(h)adra (a semi-autobiographical account of epilepsy that is likewise braided with graphic devices signaling the protagonist's inner state). Gulledge's figures, word balloons, and symbols routinely break out of her panel grid — in fact, there is not one page that obeys a strict, unbroken paneling — and the layouts are ceaselessly dynamic. Immersive full bleeds are frequent. In short, the book is a staggering exercise in expressive drawing and page-making. Story-wise, though, Mona Starr feels a bit thin and undeveloped to me. Despite hints that other characters may also struggle with mental illness or disability, and despite the plot's emphasis on seeking "help" and community, the novel feels very much absorbed by Mona's mental state and Gulledge's exhortations to embrace one's creativity. The book feels idealized, dreamy, and self-involved; Gulledge's artistic bravura, the sheer busyness of her pages, doesn't let the depression seem real. Everything is couched in terms of artistic therapy, self-study, and a self-improvement "project." Mona's counselor is introduced at the start, before Mona's depression has manifested narratively, and the greater context is emphatically reassuring. Much of the book consists of poetic self-reflection, heightened by the overflow of visual metaphor, as if in confirmation of Mona's creative "genius" (a personality test labels her "the potentially unstable visionary type"). Familial and social complexity take second place to exploring Mona's state of mind through ravishing visuals. The singular focus on Mona's feelings and self-conception would probably be smothering in bare prose; only Gulledge's ecstatic imagery gives the story life and depth. The result is heady and interesting but, I'm tempted to say, less novelistic than an exercise in didactic self-help. Somehow, the book manages to be at once lyrical, spectacular, and a confidently crafted exercise in comics, yet also frustratingly under-done, as if Gulledge couldn't quite take distance from what is, after all, a kind of exhortative autofiction. But here's the deal: I enjoyed reading Mona Starr, and it has moments that, on re-reading, still get me choked up. The book's conclusion is calming and gratifying, and I cannot deny Gulledge's hard-won insight. I am pretty sure that some readers will be affirmed, and perhaps even forever changed, by reading this book. I wouldn't recommend Mona Starr for complex, intersubjective storytelling, but will remember its powerful evocations of feelings and states of mind, as well as Gulledge's confident artistry.

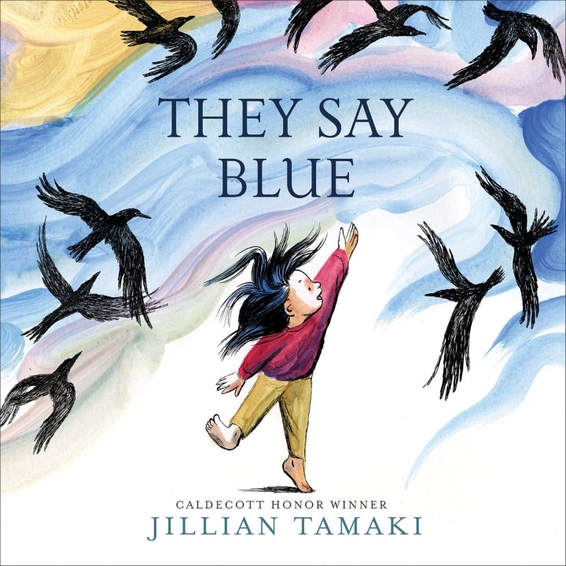

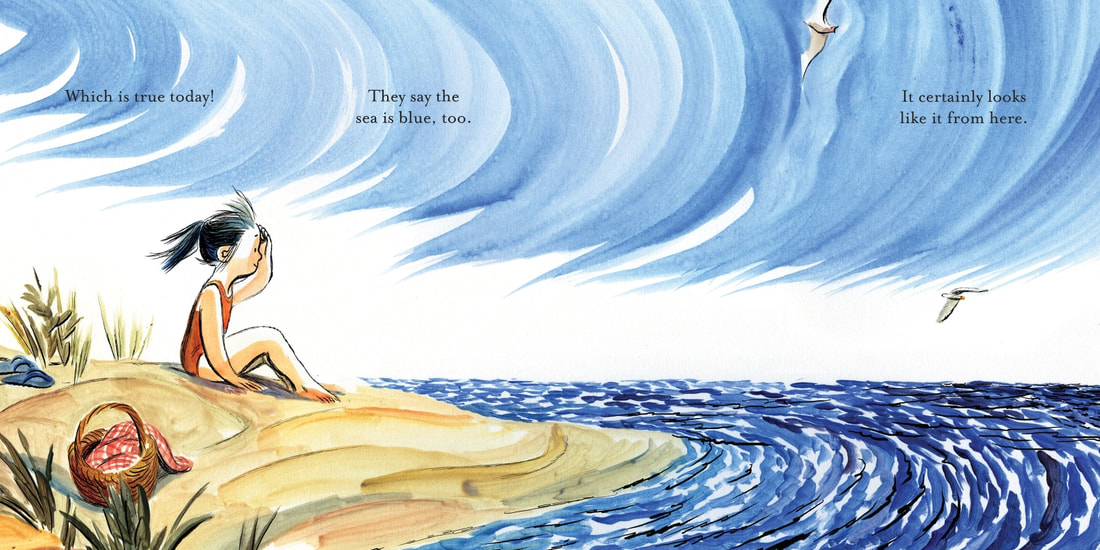

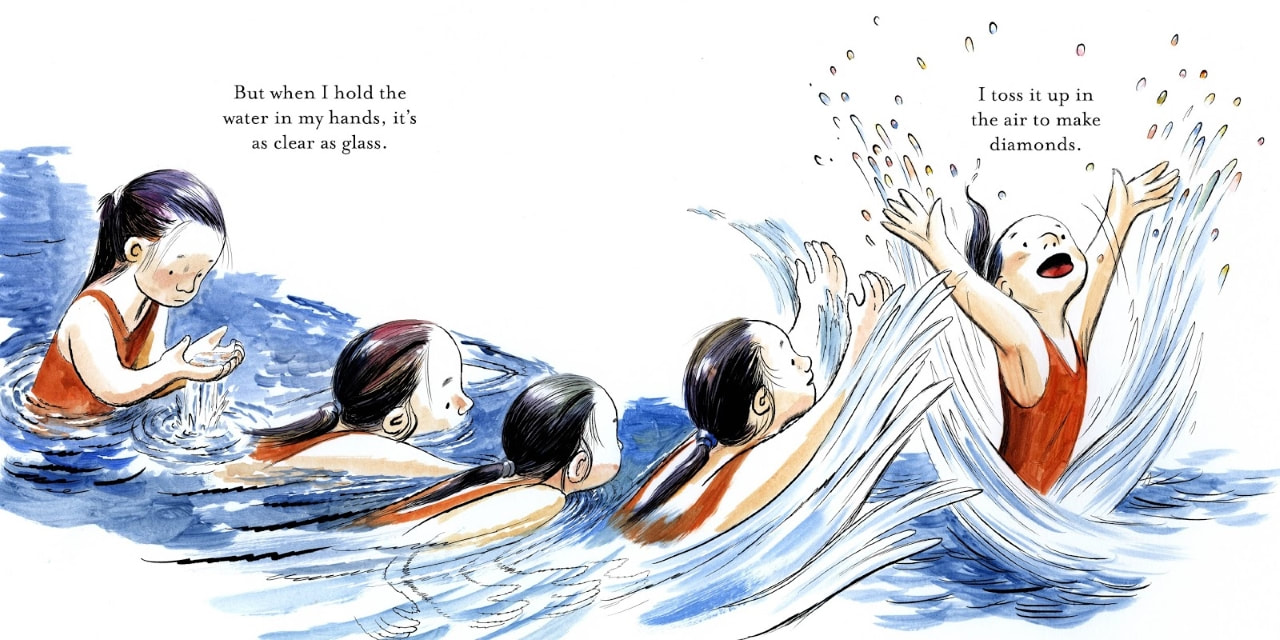

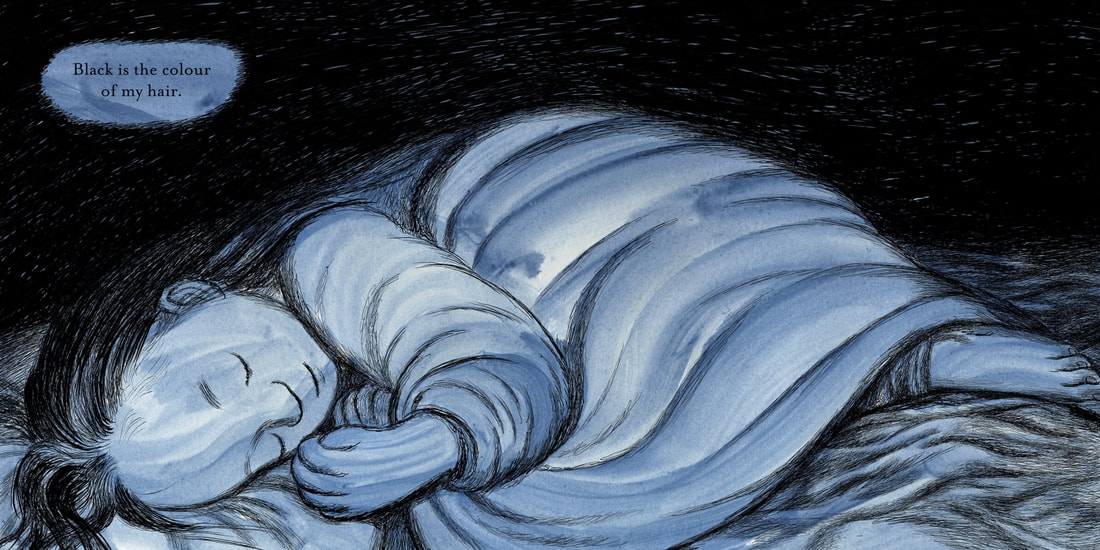

They Say Blue. By Jillian Tamaki. Abrams Books for Young Readers, March 2018. ISBN 978-1419728518. $17.99, 40 pages. Jillian Tamaki (Skim, This One Summer, SuperMutant Magic Academy, Boundless, much more) has just done her first children's picture book, They Say Blue. It's a dream: a lyrical, drifting book about seeing and not seeing, about a world of colors, about raw perception but also how we reflect upon and try to make sense of our perceptions. Painted in flowing acrylics on watercolor paper, with overlays of inked drawing via Photoshop, They Say Blue consists almost entirely of full-bleed double-spreads dotted with short, vigorous bursts of text. Lavishly illustrated yet sparsely written (roughly twoscore sentences run through its twoscore pages), it is less a storybook than a visual poem, liquid, freely expressive, and unpredictable. It focuses on the aesthetic sense and restless intelligence of a young girl with an artist's eye, for whom ordinary things can be extraordinary. The young narrator treats common sights and happenings as festivals of color, light (or darkness), and warmth, even as she sees the world around her in a here-and-now, everyday sort of way. She comes across not as some idealized Wordsworthian poet-child (though the book does partake of that spirit, a bit) but as a believably curious and engaged girl. Wonder and watch are key words, and wonder well describes my own response to the book. In other words, They Say Blue is a credible and lovely evocation of a child's creative eye and voice. It recalls, for me, the pithy matter-of-factness of Krauss and Sendak's A Hole Is to Dig, or the free-associative riffing of Crockett Johnson's Harold. It's more visually extravagant than either of those, though, recalling how the modernist here-and-now picture books of the early 20th century, the kind championed by Lucy Sprague Mitchell and Margaret Wise Brown, captured children's daily lives and intimate concerns with simplified, streamlined prose-poetry yet also, often, with rapturous, brilliant images. Tamaki is working that same ground, in (as she has said) a quite traditional way. It's a tradition less about story than about a child's looking and thinking, that is, about being in the world. I think of Brown's books with Leonard Weisgard (such as The Noisy Book, The Little Island, and The Important Book) or of course her work with Clement Hurd (most famously Goodnight Moon) -- books about ordinary sensations or the reassuring rhythms of life. They Say Blue, you can tell by its very title, is about the young girl stacking up what "they" say against what her own experience tells her. It begins with a nonfigurative spread of pure blue -- a field of overlapping brushstrokes -- and the simple observation, They say blue is the color of the sky. But, as we turn the page, then the narrator measures what "they say" against her own vision, in this glorious spread: Turning again to the next spread, we see the girl swimming through, gazing at, and splashing in seawater: five drawings of her combined into a single image. In picture book critics' parlance, this is a clear case of simultaneous succession or continuous narrative -- but to me the important thing is that it shows the girl's immersion in experience, and her way of questioning what she is told, but then also reveling in what the world gives: But just as important as these rhapsodic passages are subtle ones that chip away at the idealization of childhood. My favorite is a series of two openings that together raise up but then undercut an idyllic fantasy. The first shows our narrator sailing in an imaginary boat over a field of grass "like a golden ocean" (more simultaneous succession: delightful movement). The next, though, shows a fairly bleak, rain-sogged landscape and the girl trudging homeward through foul weather, dragging her backpack behind her against a sky of grim clouds and dull grass. She concedes, It's just plain old yellow grass anyway. I can almost hear the weariness in her voice. Thankfully, it doesn't last, but I love the way Tamaki works these bum notes into the book. Make no mistake: They Say Blue is gentle. It is affirming. But I like the way it registers moments of doubt, bewilderment, and everyday muddling. Its poetry is an everyday sort of poetry, as in, Black is the color of my hair. / My mother parts it every morning, like opening a window. Opening a window on new ways of seeing familiar things is exactly what the book does. Many comics artists struggle when moving into picture books, but They Say Blue engages picture book form and tradition knowingly. Tamaki's recent interview with Roger Sutton at The Horn Book shows how well she knows the form, and artistically she takes to the picture book as if it were an answer to a question she has been asking. In a conversation with Eleanor Davis at The Comics Journal last summer, Tamaki admitted that "I can feel increasingly confined by the image part of comics," and reflected that, at least "for more commercial works, the images [in comics] need to be a lot more literal." She described herself as trying to "stretch that word-image relationship." More recently, in an interview with Matia Burnett at Publishers Weekly, Tamaki contrasted the experience of making comics with the experience of making picture books: They’re pretty different. The poetry and distillation of kids’ books, in word and image, is a completely different challenge. A lot of comics [work] is just grinding out pages, if the images communicate what’s happening, that’s usually good enough in a pinch. A picture book’s images have to evoke, which is much more ephemeral. My sense is that They Say Blue exercises a different part of Tamaki's artistry, while still being very clearly a Jillian Tamaki book. I'm glad. The book is beautiful, a work of deft visual poetry. It confirms that, as Eleanor Davis put it, "there is no one who is better."

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed