|

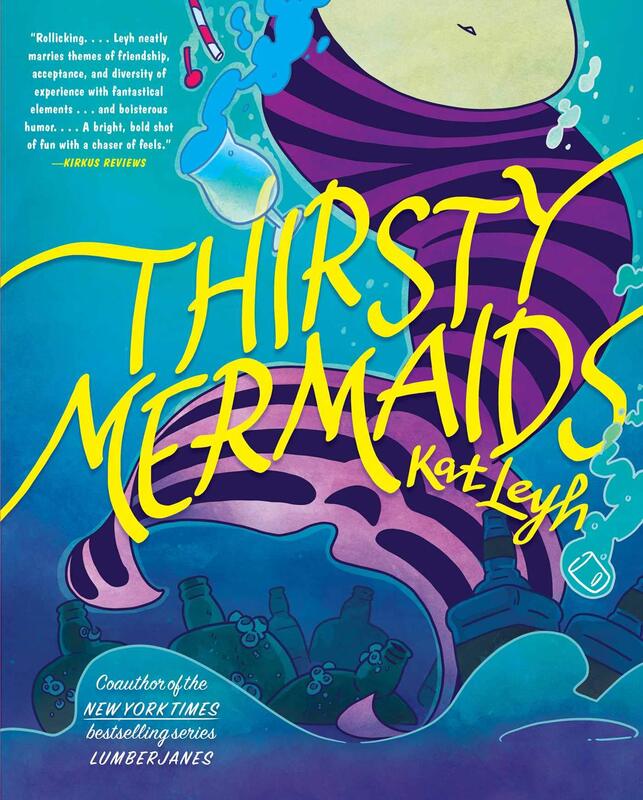

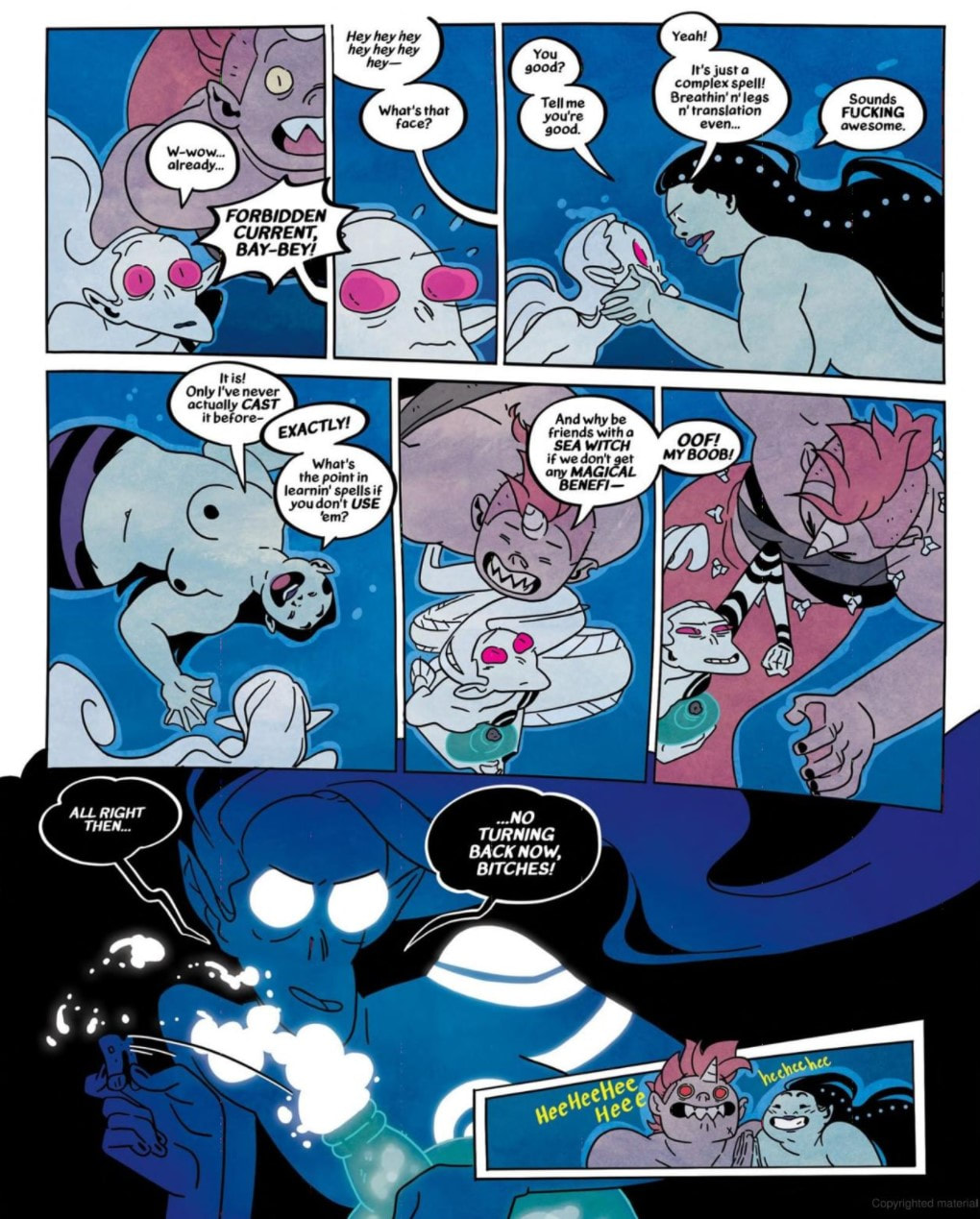

Thirsty Mermaids. By Kat Leyh. Gallery 13 / Simon & Schuster, 2021. ISBN 978-1982133573, $US29.99. 256 pages, hardcover. Briefly, Thirsty Mermaids is an absolute ass-kicking delight of a graphic novel, a riotous yarn about three loopy mermaids who, thanks to a drunken binge and some iffy magic, get stranded on dry land in human form. In what starts as a sort of screwy Disney parody, the three mermaids, Pearl, Tooth, and Eez, find themselves part of our world, marooned at a seaside tourist trap (very much Spring Break territory) and taken in by a kindly bartender, Viki, who soon becomes part of their friendship “pod.” What ensues is a series of raucous escapades, ever escalating, as the three mermaids struggle to pass as human, make sense of human bodies and customs, and find landlubber jobs, all while hoping that the spell that humanized them can be reversed so that they can return to the sea. Author Kat Leyh is known for co-writing the Lumberjanes series and for the exquisite middle-grade graphic novel Snapdragon (reviewed here recently). I guess Thirsty Mermaids is what happens when she is not working specially for young readers. Make no mistake, this is a ribald comic, full of drunken humor, F-bombs, and, often, naked mermaids. So, this is Leyh working blue. From the start — a great drunken belch that shatters the Romantic loveliness of the undersea setting — we understand that our three freewheeling, hard-drinking mermaids have no Fs left to give. From binge to hangover to regrets, this is a story of them screwing up, a sort of R-rated comedy of friendship amid bad behavior (Leyh's original working title for it was Merbitches). Oddly enough, though, the whole thing feels quite innocent and good-natured. If the book has a potty mouth, there is not one mean-spirited bone in its body. Sure, I wouldn’t hand it to a ten-year-old (and, really, the hardcover format and high cover price seem designed to steer kids away). Then again, I wouldn’t try to wrest it from a ten-year-old’s hands either. I can imagine certain teenage readers, especially those raised on Disney, delighting in its raw humor and affirming characterizations. If the story of Thirsty Mermaids starts out as a romp, it gains in depth and sympathy as it goes. While Pearl and Tooth take on human jobs and relationships, Eez struggles with depression and confusion, separated as she is from the source of her identity and her magic. From near-constant chuckles to a nervous empathy with the characters, I found myself pulled in, deeper and deeper — ultimately into what turned out to be a layered story with a climax so awesome that I literally mouthed expletives when I got to it. No lie! What I observed of Snapdragon applies here: an inclusive, queer-positive ethos; vivid, gutsy cartooning; a mix of irrepressible drawing and narrative subtlety. Yep, that’s Kat Leyh for you. Man, is she good. Thirsty Mermaids isn’t “for" children, but it’s a charming adult comedy in dialogue with childhood stories. Its pages are inventive, elastic, color-drenched, and wild — they hit that impossible sweet spot between rambunctiousness and elegance. I can’t think of a recent comic that has given me more spontaneous pleasure.

0 Comments

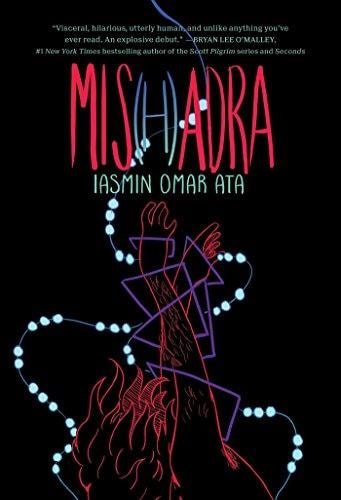

Mis(h)adra. By Iasmin Omar Ata. Gallery 13/Simon & Schuster, Oct. 2017. ISBN 978-1501162107. $25.00, 288 pages. Mis(h)adra, a sumptuous hardcover graphic novel, marks a startling print debut for cartoonist and game designer Iasmin Omar Ata, and has just been nominated for an Excellence in Graphic Literature Award (as, hmm, an Adult Book). Begun as a webcomic serial (2013-2015), its book form comes courtesy of a fairly new imprint, Gallery 13. Ata, who is Middle Eastern, Muslim, and epileptic, has described Mis(h)adra as "99.999% autobiographical" and "monthly therapy," but it's officially fiction: the story of Isaac Hammoudeh, a college student struggling to live with epilepsy, who seesaws back and forth from hope to hopelessness. The book's Arabic title, says Ata, brings together mish adra, meaning I cannot, and misadra, meaning seizure (perhaps it also echoes the word حضور, meaning presence?). Isaac desperately needs, yet cannot bring himself to accept, the help of family and friends, most particularly his new confidante Jo Esperanza (aha), who, to stay spoiler-free, I'll say faces profound challenges of her own. Mis(h)adra follows Isaac from despair and withdrawal to renewed hope, with Jo as his loving, sometimes scolding companion. The work is at once emotionally raw and aesthetically elaborate, bursting with style. While anchored in a familiar, manga-influenced look, one of simplified faces and flickering details, Mis(h)adra overflows with gusty aesthetic choices. Ata conveys the physical as well as psychological effects of epilepsy via fluorescent colors, exploded layouts, and the braiding of visual symbols: eyes, both literal and figurative, which are everywhere; strings of beads or of lights that ensnare Isaac; and floating daggers, which represent the threatening auras that warn him of oncoming seizures. The art is transporting, the seizures brutal and disorienting, yet beautiful. Tight grids give way to floating layouts. Bleeds are common, with lines sweeping off-page. Faux-benday dots, lending texture, are constant. Colors are bold and form a distinctive, non-mimetic system: pages come in pale yellow, sandstone brown, bright or dusky pink, and pure black; green and blue are used sparingly, often violently. The linework is not black but a dark purple, except on the pure-black pages, where lines of bright candy red assault the eye. Mis(h)adra renders epilepsy as a bodily and menacing experience. The story is not quite so surefooted. Only Isaac and Jo, and truthfully only Isaac, emerge as full people; almost everyone else is less a character than an indictment of normate society's insensitivity and cluelessness. The depiction of academic life is hard to credit. An explosive climax, shivering with energy and violence, gives way to an anticlimactic, fizzling resolution. Really, it seems that the book could go on and on with Isaac's struggle, but Ata simply ends because, well, a book has to stop. I felt as if the story were ending and then restarting over and over, uncertain of how to find its way. Mis(h)adra, then, is not a practiced piece of long-form writing. But it is testimony to the power of comics to create a distinct visual world, and to make a state of mind, or soul, visible on the page.

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed