|

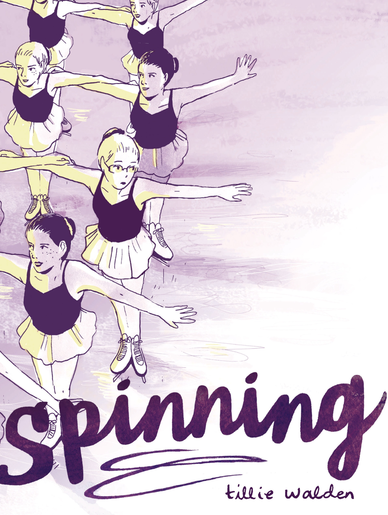

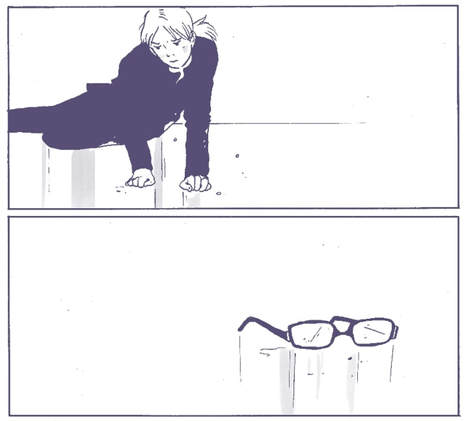

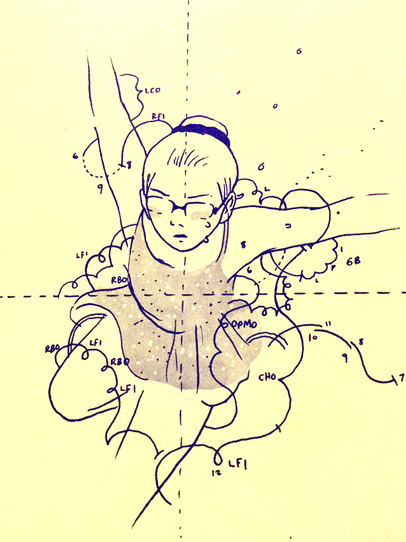

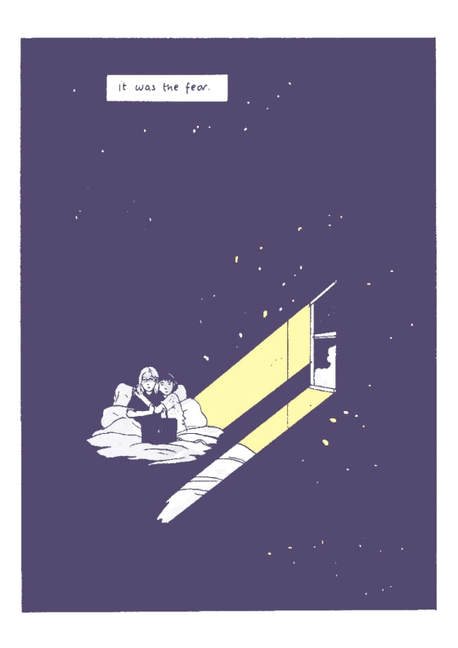

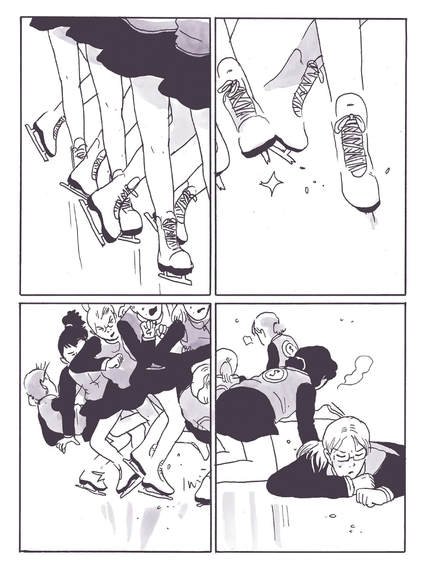

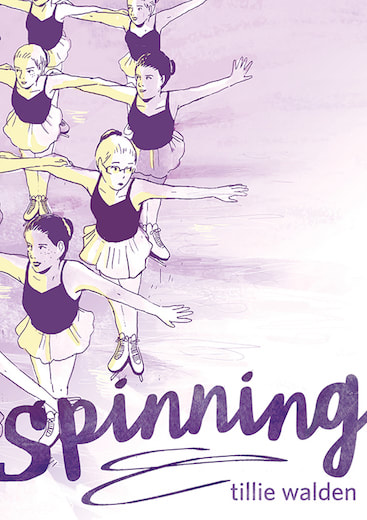

Spinning. By Tillie Walden. First Second, 2017. ISBN 978-1626729407. $17.99, 400 pages. Nominated for a 2018 Excellence in Graphic Literature Award. The feeling of waiting curbside for a ride in the predawn cold, watching headlights sweep through the darkness. Of peering out windows on sleepy car rides. Of early-morning arrival at the ice rink. Of locker rooms, benches, and earbuds, of lacing up your ice skates, everyone in their own little orbit, quietly, tensely readying themselves. Of being the new girl, of being sized up to see if you are “a threat.” Of skating across the ice, jumping and falling, your eyeglasses flinging off and away. The feeling of a teacher’s hands on your shoulders, helping you on with your jacket, and the inward recognition that you are gay. Of sidelong glances in a classroom, “dizzy” with longing. Of walking in a crowd of girls, talking about Twilight (Edward or Jacob?), while hiding who you are. Of playing “never have I ever” with the girls while hiding who you are. Of passing. Of trying to recreate, as a skater, with your body, the “tiny graphs and charts,” the “intricate patterns and minute details,” of an instruction book. Of desperately holding hands during a synchro skating routine. Even as the speed is “ripping them apart.” Holding on for dear life. Of friendship as a lifeline. As rivalry and sympathy intermingled. The feeling of being judged, as your teammate speeds up to walk a few paces ahead of you. Of winning and losing, of exulting in first place and weeping when you lose. Of knowing that you cannot always be the one that wins. The tears of your competitors, and your own. The dread of the school bully, rendered faceless in memory but still so powerfully there. Your hands nervously playing in your lap, or gripping your knees. Your teacher questioning you. The feeling of falling asleep next to your brother by the light of a laptop screen. Of crying from the makeup in your eyes. Of pulling a blanket up over your head. The sight of the girl you like stretching, and quietly smiling at you. The feeling of being alone with her. Of love, bounded by fear. Of kissing: I didn’t know it would feel like that. Of capering in a hotel room, alone, free from anyone’s judgment. Gazing into your reflection in the surface of a vending machine. The felt “eternity” of a three-minute skating routine. Feet in the air, in mid-jump. Stares and glances. Stares and glances. Girlhood as competitive arena. The feeling of being tested, and failing. Of being alone in a closed room with a tutor who treats you as a thing. The memory of his hand. The feeling of coming out, in a broad, silent room crossed by a slanting beam of sunlight, your mother huddled, tense. Of coming out to your music teacher, in a loving embrace. The sensation of drawing. Of time collapsed into drawing. Of a skate remembered as a nervous, tight grid of panels. Of moves and thoughts flickering. Of falling. Oh my god / my coach is looking at me / the audience shit / the judges The sight of oncoming headlights like round staring eyes. The memory of his hand. Of quitting skating. Walking away.

Driving away, crying. Of returning to the rink, once more, just to prove that you can leave. (There’s no way I could forget.) For all these experiences, and many more--so finely observed, so precisely caught, in a style at once tense and graceful, minimal yet conveying every telling detail, rigorous and yet so light and free—for all this, Tillie Walden’s memoir Spinning is an unforgettable comic, the kind that gets inside your mind and heart. I cannot recommend it highly enough.

0 Comments

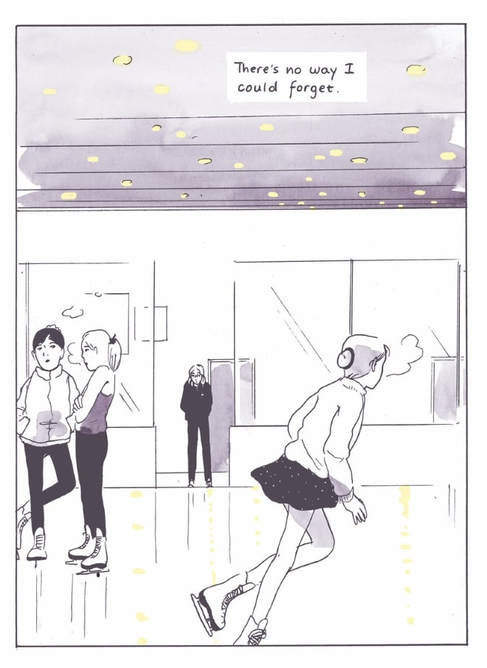

Lost in NYC: A Subway Adventure. Written by Nadja Spiegelman, illustrated by Sergio García Sánchez, and colored by Lola Moral. TOON Books, 2015. ISBN 978-1935179818. $16.95, 52 pages. A Junior Library Guild Selection. From time to time, Faves will offer brief capsule reviews of what I think of as key titles in my library: Lost in NYC is my favorite of the TOON Graphics to date (among the new books, that is—the translations of Fred's Philemon are also a delight). A short comic in picture book format, but as dense with detail as a graphic novel, Lost in NYC works in busy, hide-and-seek, Where’s Waldo? mode. It rewards attention, in fact perfectly demonstrates the idea that comics are a rereading medium. A valentine to New York and its subway system (the book is licensed by NYC's Metropolitan Transportation Authority), Lost in NYC depicts a school field trip to the Empire State Building, and gives a wealth of info about how to navigate the Big Apple (including a detailed subway map). Along the way, it tells the story of an awkward “new kid” in school who has just moved, feels out of place, and doesn’t trust anyone—until he and his field trip partner get lost and have to figure out how to rejoin their school group. The story depicts the new kid’s loneliness and bluff attempts to deny it with a rough honesty, but (unsurprisingly) reaches an uplifting conclusion: the field trip becomes a rite of passage, in a manner familiar from many picture books about first experiences. The pages, though, are the thing; they dazzle in their intricacy and attention to geography and culture. Sánchez’s cartooning is lively yet sly. The packed spreads, so much fun to wind through, turn up small surprises with each reading. Often the spreads use continuous visual narrative (i.e. repeated images of characters moving across a single page or opening) to show the kids negotiating the crowded city. Along the way, Lost in NYC has a lot to say about city life, mobility, access, and diversity (the art implies myriad mingled cultures). Thus the book invites comparison to other recent children's titles that envision cities as vast and pluralistic communities (for example, Matt de la Peña and Christian Robinson’s much-admired 2015 picture book, Last Stop on Market Street). It also tackles the challenges of moving and building new friendships. The plot is simple, and the outcome never in doubt, but the book puts the teeming cityscape to great use, not just as a backdrop, but as the main attraction. By way of bonus, Lost in NYC incorporates photos and historical facts (the field trip conceit allows a teacher character to lecture and explain); further, the book's back matter, as is typical of TOON Graphics, offers a wealth of contextual lore, social, technological, and architectural. Really, this is an overstuffed delight.

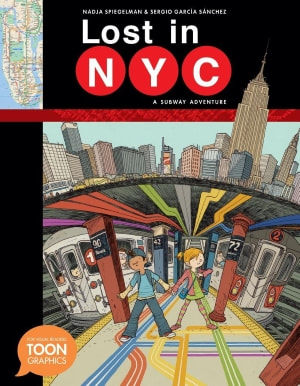

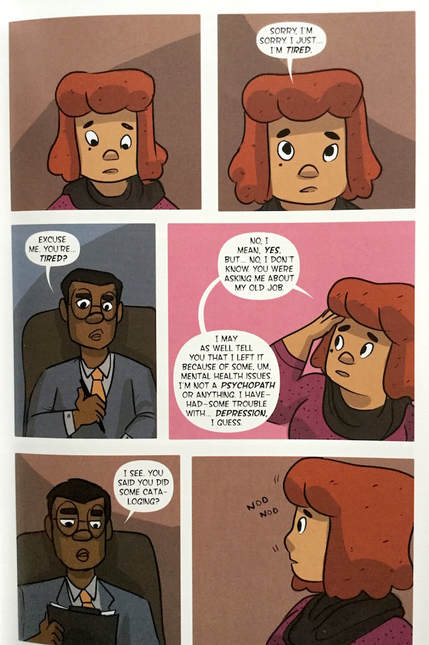

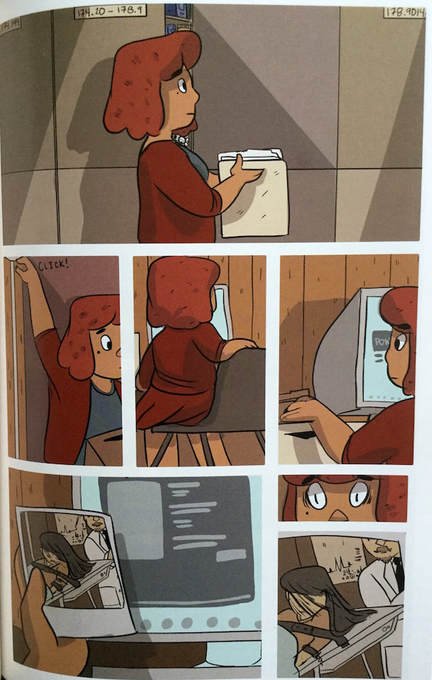

Archival Quality. Written by Ivy Noelle Weir, illustrated and colored by Steenz. Oni Press, March 2018. ISBN 978-1620104705. $19.99, 280 pages. A Junior Library Guild Selection. Archival Quality, an original graphic novel out this week, tells the story of a haunted museum: a ghost story. It also tells about living with mental illness. The protagonist Cel, a librarian struggling with anxiety and depression, takes a job as archivist of a spooky medical museum that once served as an asylum (my friend, medical archivist and comics historian Mike Rhode, should check this out). The catch: she has to live in an apartment on the premises and do her work only in the dead of night. Soon she begins to witness... happenings that she cannot explain. Her boss, the museum's curator, and her coworker, a librarian, tiptoe around her, knowing more than they will say. Cel, who lost her previous job due to a breakdown, is understandably perplexed and triggered by their evasions, and by the fact that no one seems to believe her reports of odd doings. She begins to have frightful dreams: flashbacks that evoke the shadowy history of women's mental health treatment. The plot, which like many ghost stories gestures toward the fantastic (as Todorov defined it), finally veers toward the outright marvelous as Cel investigates the case of a young woman from long ago whose presence still lingers about the place. Cel, as she works to solve that case, is by turns fragile and angry, defensive and determined—a complex character, as is the curator, at first her foil, later her ally. The story takes quite a few turns. To be honest, Archival Quality's title and look did not prepare me for its uneasy exploration of mental health treatment—or rather, the social and psychiatric construction of mental illness. As I read through the novel's first half, Steenz's drawing style struck me as too light, undetailed, and schematically cute for the story's atmosphere of updated Gothic. Cel, with her snub nose, button eyes, and moplike hair, reminded me strongly of Raggedy Ann, and in general Steen's characters have a neotenic, doll-like quality. The settings seemed too plain to conjure up mystery and dread; the staging seemed too shallow, with talking heads posed before blank fields of color or swaths of shadow, lacking particulars. Steenz favors air frames (white borders around the panels, rather than drawn borderlines) and an uncluttered look. This did not jibe with my expectations of the ghost story as a genre. But as the plot deepens, and Cel's dreams and visions overtake her, Weir and Steenz together generate suspense. The pages deal out a number of small, quiet shocks: Further, Steenz's sensitive handling of body language brings the characters, doll-like as they are, to life. The book becomes tense, involving, and, as we say, unputdownable. Weir and Steenz's back pages tell us that the two enjoyed a close working relationship, and you can tell this from the story's anxious unwinding. This is unusually strong storytelling, and a complicated, coiled plot, for a first-time graphic novel team. Clearly, Weir and Steenz are simpatico artistically—and ideologically too, I think, sharing a progressive and feminist outlook that shapes cast, character design, characterization, and plot. I will admit that not everything about Archival Quality works for me. The plot, on the level of mechanics, seems juryrigged and farfetched, that is, determined to pull characters and elements together for the sake of symbolic fitness, without the sort of realistic rigging that the novel seems to be striving for. In other words, certain things happen simply because they have to happen. Further, some elements of the story, rather big elements I think, are palmed off in the end because Weir and Steenz don't seem to be interested in working out the details. At the closing, I had the feeling that a Point was being made, rather than a novel being rounded off (to be fair, I often react this way to YA fiction, even though I know that didacticism is crucial to the genre). Still, Archival Quality, behind its coy title, offers a gutsy exploration of mental health treatment, an eerie ghost story, and characters who renegotiate their relationships with credible human frailty and charm. A most promising print debut, and a keeper.

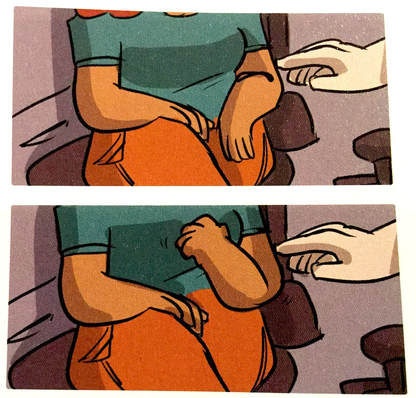

Mis(h)adra. By Iasmin Omar Ata. Gallery 13/Simon & Schuster, Oct. 2017. ISBN 978-1501162107. $25.00, 288 pages. Mis(h)adra, a sumptuous hardcover graphic novel, marks a startling print debut for cartoonist and game designer Iasmin Omar Ata, and has just been nominated for an Excellence in Graphic Literature Award (as, hmm, an Adult Book). Begun as a webcomic serial (2013-2015), its book form comes courtesy of a fairly new imprint, Gallery 13. Ata, who is Middle Eastern, Muslim, and epileptic, has described Mis(h)adra as "99.999% autobiographical" and "monthly therapy," but it's officially fiction: the story of Isaac Hammoudeh, a college student struggling to live with epilepsy, who seesaws back and forth from hope to hopelessness. The book's Arabic title, says Ata, brings together mish adra, meaning I cannot, and misadra, meaning seizure (perhaps it also echoes the word حضور, meaning presence?). Isaac desperately needs, yet cannot bring himself to accept, the help of family and friends, most particularly his new confidante Jo Esperanza (aha), who, to stay spoiler-free, I'll say faces profound challenges of her own. Mis(h)adra follows Isaac from despair and withdrawal to renewed hope, with Jo as his loving, sometimes scolding companion. The work is at once emotionally raw and aesthetically elaborate, bursting with style. While anchored in a familiar, manga-influenced look, one of simplified faces and flickering details, Mis(h)adra overflows with gusty aesthetic choices. Ata conveys the physical as well as psychological effects of epilepsy via fluorescent colors, exploded layouts, and the braiding of visual symbols: eyes, both literal and figurative, which are everywhere; strings of beads or of lights that ensnare Isaac; and floating daggers, which represent the threatening auras that warn him of oncoming seizures. The art is transporting, the seizures brutal and disorienting, yet beautiful. Tight grids give way to floating layouts. Bleeds are common, with lines sweeping off-page. Faux-benday dots, lending texture, are constant. Colors are bold and form a distinctive, non-mimetic system: pages come in pale yellow, sandstone brown, bright or dusky pink, and pure black; green and blue are used sparingly, often violently. The linework is not black but a dark purple, except on the pure-black pages, where lines of bright candy red assault the eye. Mis(h)adra renders epilepsy as a bodily and menacing experience. The story is not quite so surefooted. Only Isaac and Jo, and truthfully only Isaac, emerge as full people; almost everyone else is less a character than an indictment of normate society's insensitivity and cluelessness. The depiction of academic life is hard to credit. An explosive climax, shivering with energy and violence, gives way to an anticlimactic, fizzling resolution. Really, it seems that the book could go on and on with Isaac's struggle, but Ata simply ends because, well, a book has to stop. I felt as if the story were ending and then restarting over and over, uncertain of how to find its way. Mis(h)adra, then, is not a practiced piece of long-form writing. But it is testimony to the power of comics to create a distinct visual world, and to make a state of mind, or soul, visible on the page.

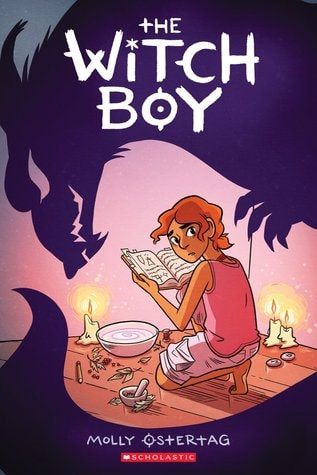

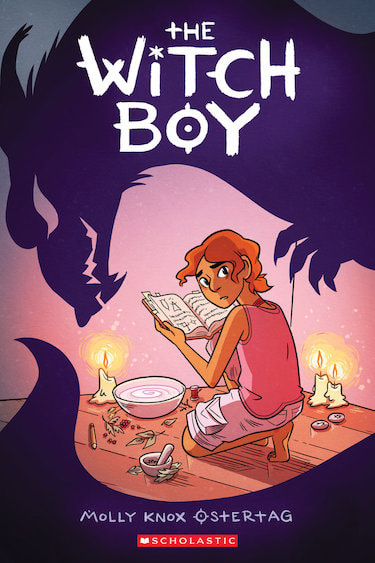

The Witch Boy. By Molly Knox Ostertag. Scholastic/Graphix, 2017. ISBN 978-1338089516. $12.99, 224 pages.I met Molly Knox Ostertag at the Chevalier’s event on March 15, and that inspired me to read, at last, The Witch Boy, a talked-about graphic novel from last fall and now a finalist for the Excellence in Graphic Literature Awards. So, in the spirit of catching up: Billed as a middle grade fantasy, The Witch Boy envisions a clan of witches and shapeshifters on the edges of human society who subscribe to a strictly gendered division of roles: witches are women, and shapeshifters men. However, protagonist Aster is a boy whose magic leans toward witchery, not shifting. This is taboo. Aster’s family anxiously clings to its binarism; his witching strikes them as uncanny and ill-starred. This tale of forbidden skills and aspirations is also, implicitly, a coming-out story; the plot inverts the familiar premise of a girl braving to enter what is deemed a man’s field while also queering notions of gender identity. Indeed the novel exposes the unease that a queer or gender-nonconforming child can bring to an insular community. Aster, shamed and fretted over by his kin, finds support in a non-magical girl named Charlie (Charlotte), a young athlete of color whose own resistance to gender norms is quickly sketched. Charlie, blunt and unaffected, frees Aster up a bit, and helps him use his forbidden gifts to resolve a mystery that is threatening the boys of his clan—a mystery that traces back to his family’s very history of shaming those who do not fit their gender norms. The novel hurtles to an end with an outpouring of backstory from a wise grandmother who holds the key, plot-wise, and the conclusion brings not perfect harmony ("Mom and Dad don't really get it...") but acceptance and the promise of further adventures (sequels!). The Witch Boy is a promising solo debut from Ostertag, already a busy cartoonist and co-creator of several comics. She wrote, drew, lettered, co-designed, and (with help) colored the book, and the story feels personal. The artwork, expressive and clear, recalls Hope Larson for me, but Ostertag is looser and uses backgrounds more sparsely. Her storytelling pulls me through effortlessly, though at times atmosphere and setting seem too thinly (or hurriedly) drawn for full effect. The ending is baldly telegraphed, and the last threescore pages rush to get there, with hasty exposition. But I enjoy the world, including its multiracial and queer-positive families, and the fact that the grownups in it, even at their most fearful or unbending, are not caricatures but strong folk anxious to do right. There is potential for a complex series here, and I look forward to more from Ostertag. Soon, I gather!

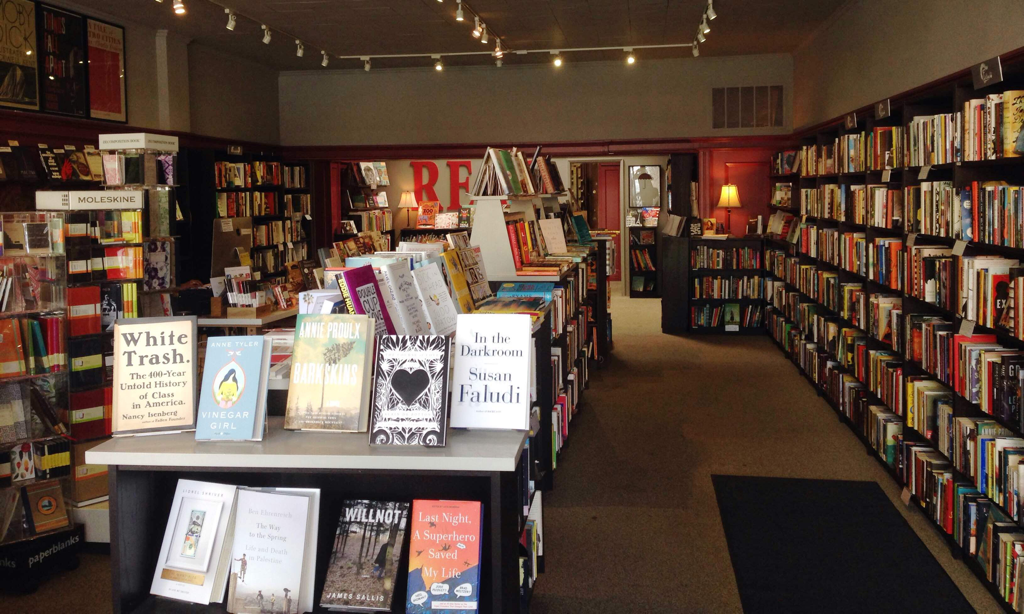

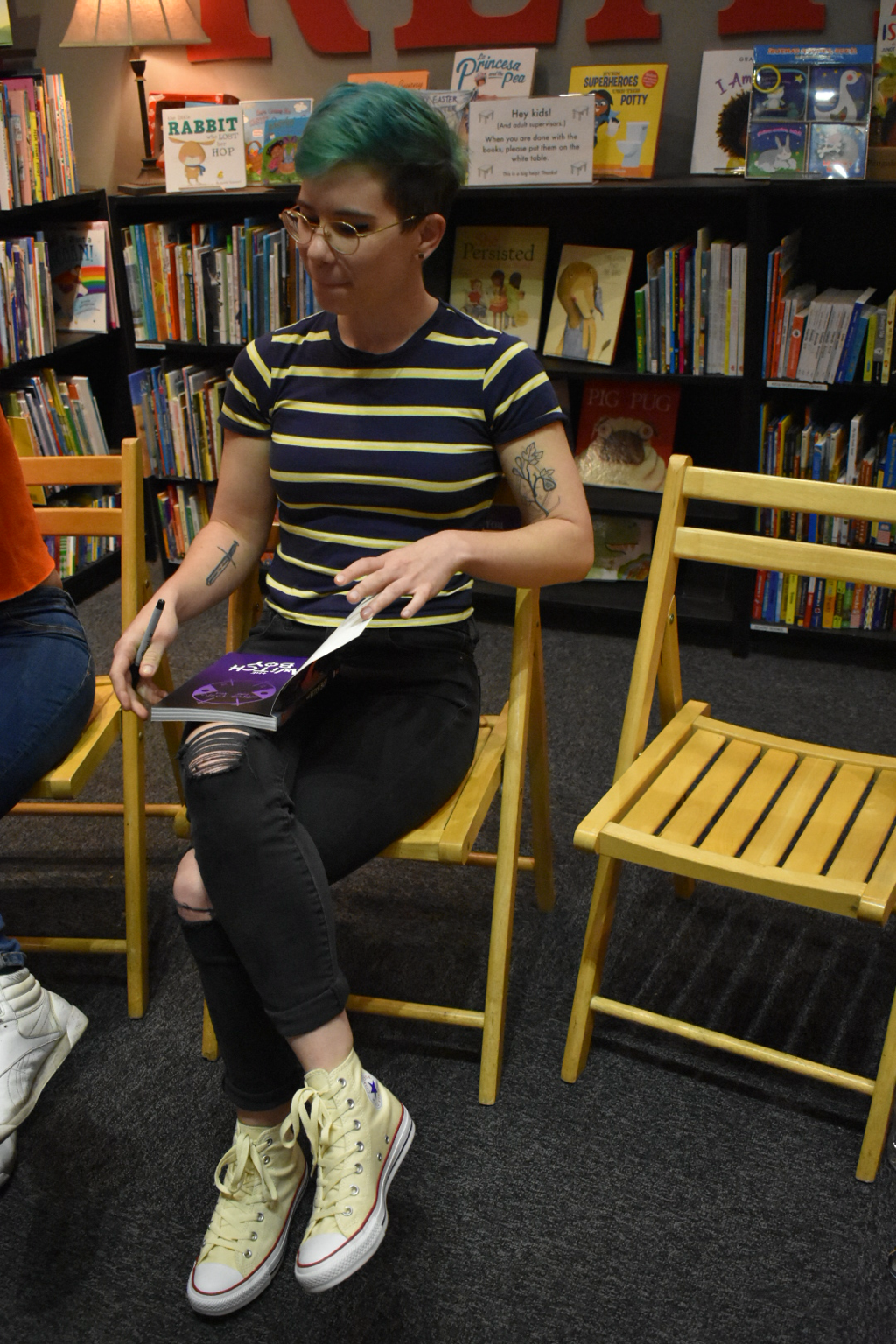

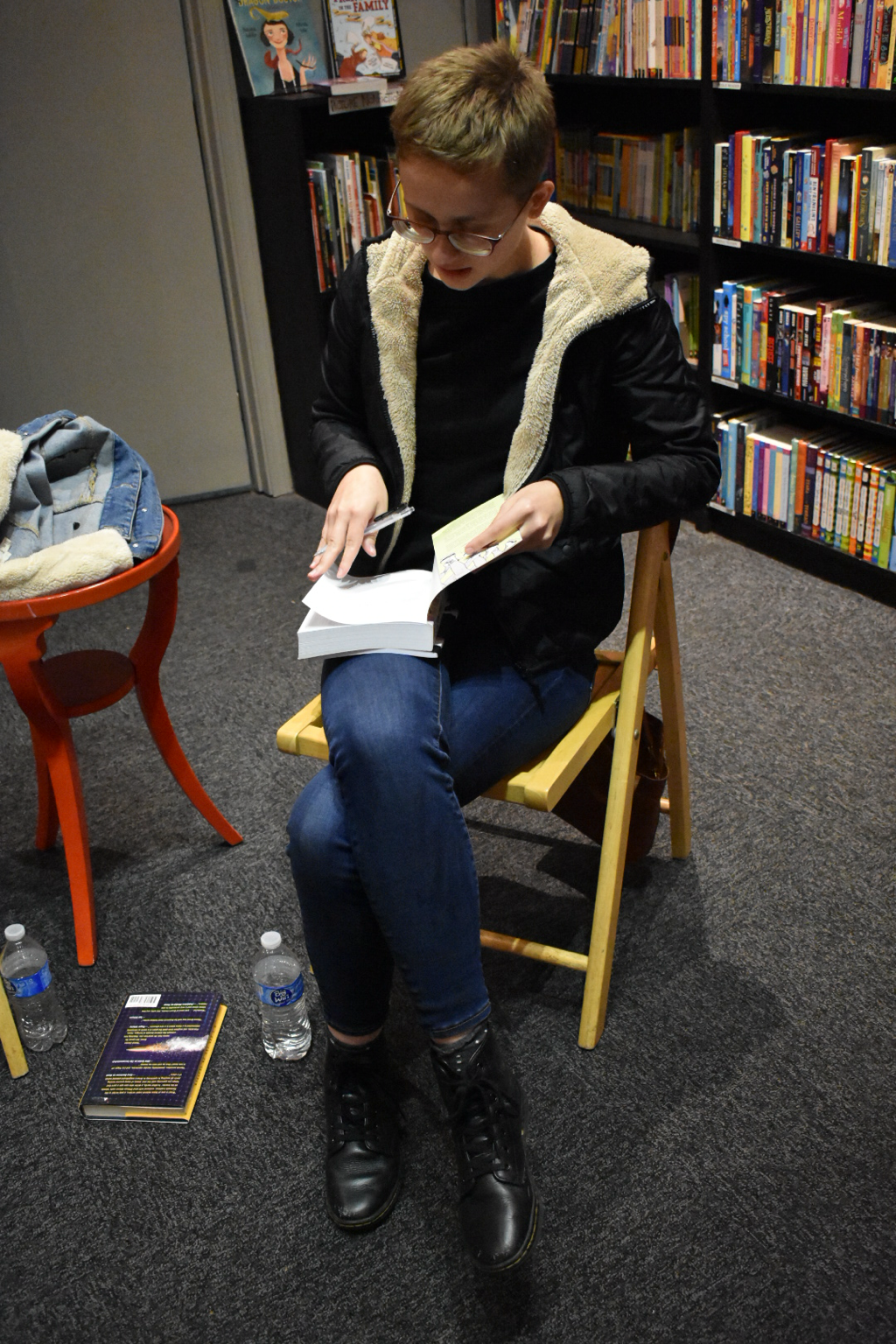

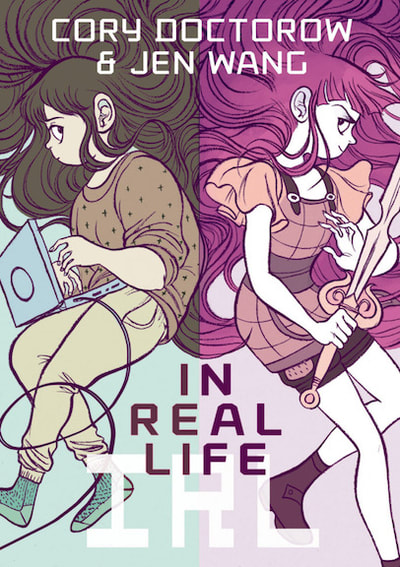

On Thursday evening, March 15, my wife Mich and I were fortunate to attend a smart, intimate, charmingly informal panel discussion at Chevalier’s Books with Jen Wang (The Prince and the Dressmaker, In Real Life), Cory Doctorow (In Real Life, Little Brother), Molly Knox Ostertag (The Witch Boy, Strong Female Protagonist), and Tillie Walden (Spinning, On a Sunbeam). Wow, what a lineup! Chevalier’s, in L.A.’s Larchmont Village, has been open since 1940, making it the oldest independent bookshop in Los Angeles. We had never been there before—but I expect that we’ll be back! Nice shop, cool space, and welcoming, with real personality and what appeared to be carefully chosen stock (the graphic novel buyer seems to have a definite POV). We arrived a few minutes late to the discussion, which took place in the children’s alcove, surrounded by books. A few rows of wooden chairs had been set up for the audience, but the space was fairly tight and the crowd small, maybe a double handful of people. Jen Wang served as emcee of sorts, sometimes referring to her phone for questions but mostly letting the conversation float along in an easy, unforced way. Yet the conversation was rich in information and insight, and covered a lot of ground: from writers’ habits (with Doctorow marveling at Anthony Trollope’s famed productivity and self-discipline), to artistic inspirations (movies, immersive theater, theme park rides, music), to elements of craft (layout; scripting versus improvising; research). The speakers were at times disarmingly honest: Wang confessed that there are times she prefers not to draw, especially when she has recently finished a project as big as The Prince and the Dressmaker. Walden confessed that the response to her memoir, Spinning, has caught her up in its own momentum in ways that impinge on her current work. Ostertag likewise admitted that she worries about the success of one book making her too self-conscious or eager to please in her future work. Walden admitted how tough it could be to field difficult, sometimes heartrending, questions and stories from young readers, especially queer readers in search of advice and assurance (she mentioned that writing a memoir seemed to open her to this kind of response). Doctorow revealed how his fiction-writing is often fueled by anger over political events, and his need to free his social media use from the constant pressure to respond to provoking political news. All showed a keen interest in each other’s work and in sharing process (Ostertag, initially somewhat reserved, seemed to open up when discussing Wang’s new book!). I loved the way the discussion wandered through big issues of audience, genre, and the depiction of sexuality and gender identity, to minute nuts ‘n’ bolts issues of page design and drawing (comics nerd moments: I just eat those up). All four creators gave me a sense of being extraordinarily busy and productive—every one of them has new irons in the fire, new books forthcoming, and so on. They got on well, unsurprisingly, with a nice collegial vibe (there were jokes about everyone now being in the First Second family, so to speak). In sum, an amazing panel—and so chill and easygoing, for such an amazing gathering of talents. After the panel, we chatted, then Mich and I bought some books and got ’em signed. I talked up this blog a bit, and informed Molly Ostertag and Tillie Walden that they had been nominated for Excellence in Graphic Literature Awards earlier that same day (they hadn’t heard!). I spoke with Jen Wang and (I think) Jake Mumm about the splendid CALA festival that they help to put on every year. A delightful experience—then I read Ostertag’s The Witch Boy when I got home (because man was I overdue). Thanks to Chevalier’s for hosting such a strong comics event!

NEWS! This morning, the organizers of the Excellence in Graphic Literature Awards announced their nominees for the first-ever slate of EGLs, to be awarded at the Denver Comic Con on June 16. The livestream of the announcement, hosted by KidLit TV, can be (re)viewed here. Also, PR Newswire has a press release including the full list of nominees. It's an interesting list, with books I love, books I admire, and books I'd like to get to know. The EGL Awards, as I posted this morning, aim to strengthen the link between comics publishing and the field of children's and Young Adult librarianship. School librarians, public librarians, and K-12 educators are well represented in the judging panels and advisory board, and indeed seem to be the Awards' center of gravity. The awards include eight categories organized by age range, as well as one diversity-themed prize, the Mosaic Award, and an overall Book of the Year prize with contenders drawn from the other categories. The age-based categories are divided into Fiction and Nonfiction for Children (Grade 5 and under), Middle Grades (Grades 6-8), Young Adults (Grades 9-12), and Adults. (You can find out more about the EGL categories at the Pop Culture Classroom, here.) It seems to me that the EGLs have been rolled out in, for comics, unusually coordinated and deliberate fashion. I expressed reservations about the seeming outlook of the Awards when I first learned of them (see the comments thread here), and continue to wonder at the Awards' judging culture and, perhaps, selective filter—all based on my guesswork, I hasten to add. It does seem likely to me that the EGLs will filter out significant parts of comics culture and book-length comics publishing. However, this is also true of other industry awards that seek to cover the whole span of book-length comics, such as the Eisners; all have blind spots, and all speak to the interests of particular communities within the comics world. That said, this first EGL slate strikes me as solid and promising, with an encouraging diversity in aesthetic, genre, and tradition. I also like the range of publishers represented (though First Second Books is clearly the favorite, with five out of the eight nominees for Book of the Year). I confess, I do see a few frank headscratchers among the nominees (what award process is without those, though?). The nonfiction choices for Children and Middle Grades are quite thin, and in general I feel more confident of the YA and Adult categories. Also, the Best of Year finalists make for, um, an odd set: apples and oranges and then some. Further, I'm not sure that all the nominees quite match the high literary aspirations implied by the Awards' name, suggesting that the "L" in EGL may be an awkward fit for some comics, even very good ones (but, um, the politics of respectability is perhaps too big a problem for one award to solve?). Here is the full list of finalists, as reported today: CHILDREN'S BOOKS Fiction

MIDDLE GRADE BOOKS Fiction

YOUNG ADULT BOOKS Fiction

ADULT BOOKS Fiction

MOSAIC AWARD FINALISTS

BOOK OF THE YEAR FINALISTS

Quite a list. I'm excited to see, for example, Liniers, Melanie Gillman, Tillie Walden, Katie Green, Thi Bui, Emil Ferris, Guy Delisle, and the team of Stacey Robinson and John Jennings. I'm also excited to see promising books from creators I don't know. The division of Awards by age range, and the list of publishers represented, perhaps indicate the Awards' intended focus and community more clearly than anything I could say. Let's see what happens. PS. It was a pleasure to see among the EGL jurors and advisors in this morning's video announcement my friends and colleagues Dr. Katie Monnin of the University of North Florida (we judged Eisners together in 2013) and Carr D'Angelo and Susan Avallone of Earth-2 Comics, my LCS!

NEWS! The first-ever set of nominations for the Excellence in Graphic Literature Awards is fixing to go live, in about an hour, thanks to KidLit TV.

The EGL Awards are sponsored and organized by the nonprofit Pop Culture Classroom, and represent an effort to tie a major comics award more directly into the worlds of children's and YA graphic novel librarianship. The Comics Journal's Alex Dueben interviewed two of the people behind the EGL Awards, John Shableski and Illya Kowalchuk, back in January (and I tentatively raised some concerns about the Awards in the comments thread). It'll be interesting to see this first slate of nominees! You can access the livestream of the nominations (10:00 am PCT, today, Thursday, March 15) at KidLit TV, here. WOW. No sooner do I finish reviewing Jen Wang's splendid new graphic novel, The Prince and the Dressmaker, than I realize that Wang and a panel of other great talents will be discussing the book at Chevalier's Books, Los Angeles's fabled independent bookstore, tomorrow night, Thursday, March 15, at 7:00pm. The details are at Chevalier's site, here (Chevalier's is at 126 North Larchmont Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90004). Wang, author of Koko Be Good (2010), co-author, with Cory Doctorow, of In Real Life (2014), and co-founder of the Comic Arts LA festival, will be joined by Doctorow, as well as two other notable comics creators, Molly Knox Ostertag and Tillie Walden. Doctorow is of course a novelist (author of Little Brother among others), columnist, tech expert and activist, and the co-editor of Boing Boing. Ostertag is the author of the recent graphic novel The Witch Boy (whose exploration of gender resonates with The Prince and the Dressmaker), co-creator of the graphic novel Shattered Warrior, and co-creator of the ongoing webcomic Strong Female Protagonist. Walden is author of the recent graphic memoir Spinning (one of 2017's most acclaimed comics) and the webcomic (soon to be graphic novel) On a Sunbeam, as well as the graphic books The End of Summer, I Love This Part, and A City Inside. This is an incredible gathering of talent. Frankly, it would be hard to imagine a stronger panel than this when it comes to the intersection of children's publishing and graphic novels, small-press and independent comics, women comics creators, and explorations of gender and sexuality in comics. I dearly hope to make this event, which I expect is going to be great!

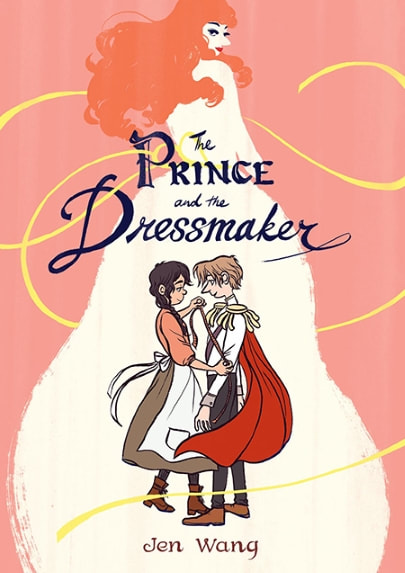

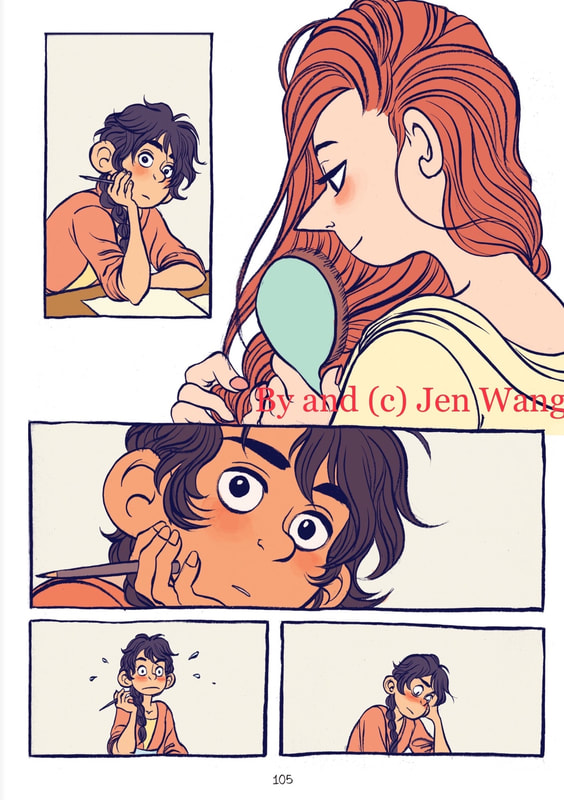

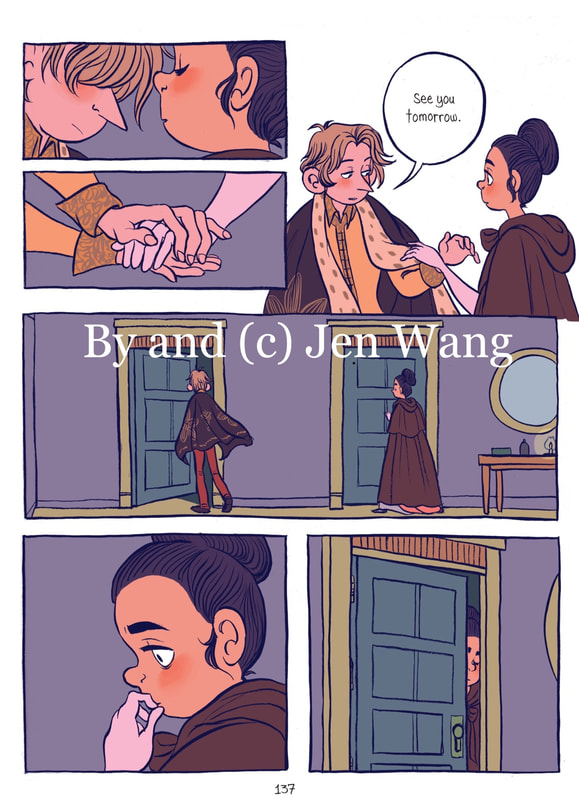

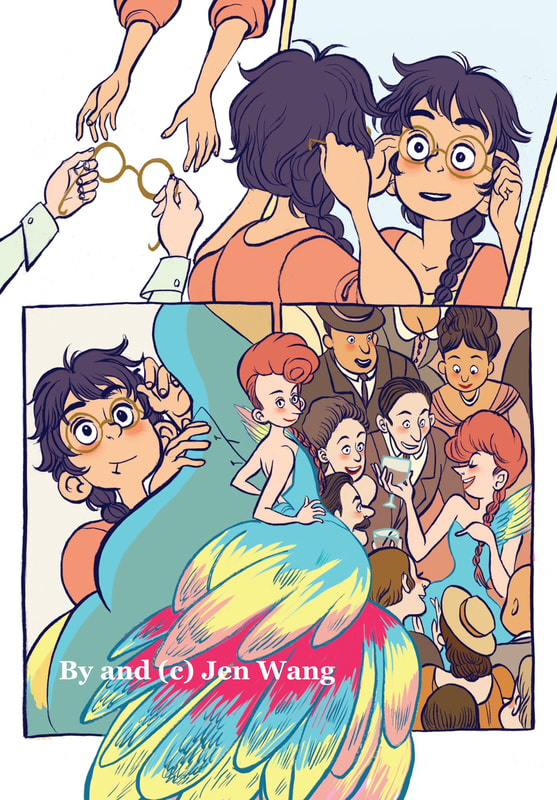

The Prince and the Dressmaker. By Jen Wang. First Second Books, February 2018. ISBN 978-1626723634. $16.99. (New to KinderComics? Check out our introductory post!) The Prince and the Dressmaker, Jen Wang’s new graphic novel, is her third, following Koko Be Good (2010) and In Real Life (2014). All her books have been well reviewed and admired, but this one is likely to be remembered as her breakout, deservedly so. A genderbending YA fairy tale romance set in a make-believe Paris on the cusp of modernity—a Belle Époque Paris with haute couture and department stores but no trace of Industrial Age grime—The Prince and the Dressmaker tells a tender story of nonconformity, the delicate art of public personhood, and desire. I especially like the way it does not editorialize about desire but instead evokes it, often wordlessly, hauntingly—without moralistic signposting and with a florid style that captures the flush of recognition and the confusion of feelings that desire can bring. A marvel of fluid, expressive cartooning, this book takes a fairly shopworn notion, that of the progressive fairy tale (often a go-to genre for feminist, gender-nonconforming subversiveness), and fills it with startling new life. It gives fresh evidence of Wang’s deftness and grace as a comics artist: her characters live, her rhythms draw this reader breathlessly in, and her pages pop. In short, this is artful work, fraught and emotionally daring, ultimately affirming, and, well, ravishing. As the above cover hints, The Prince and the Dressmaker is a prince-and-pauper fable about a process of artistic co-creation: the collaboration between a hard-working seamstress and designer, Frances, and a furtively cross-dressing prince, Sebastian, for whom Frances makes dresses. Sebastian endures his parents' attempts to marry him off to this or that young noblewoman but really only comes alive when he can venture into the world incognito, as Lady Crystallia: a fashion plate and the magnet of every elegant young lady's attention. It is Frances's skill and hard work that transform Prince into Lady; essentially, Crystallia is their joint work of art, with Frances as designer and Sebastian as model. Their clandestine partnership grants Sebastian a chance to live more freely, though only for brief, risky episodes, and Frances a chance to practice her art, but only anonymously. It's a match made in Heaven—or isn't, since each can only enjoy the work of creating Lady Crystallia by hiding or disavowing who they are. Sebastian remains closeted, and Frances remains unknown and unsung, denied the opportunity to take her skills public and fashion an autonomous career. The story tugs at this problem, and one other: that of unacknowledged, perhaps confused, desire. That is, The Prince and the Dressmaker is a love story as well as a Künstlerroman. The novel's plot is not especially devious or complex, and stakes out familiar territory. I'm reminded of feminist and queer-positive fairy tale books such as The Paper Bag Princess and King and King; feminist and queer-positive fairy tale comics like Castle Waiting, Princeless and Princess Princess Ever After; and the cross-dressing traditions of shojo manga (here slyly inverted) as well as manga's more recent explorations of transgender experience (notably, Shimura). Further, the faux-European setting, at once antique and yet salted with anachronisms in speech and manner, recalls the vague storybook Europe of Miyazaki. Familiar things, as I said. What Wang has accomplished here, though, does not boil down to a bald set of thematic or genre conventions; she wins on the details, which are myriad and lovely. The story comes across delicately, with expressive body language and telling grace notes of observation, and thankfully without intrusive narration or didactic underscoring. Frances and Sebastian have next to nothing in the way of backstory, but they remain distinct, visually quirky, well realized characters: Frances a mix of self-sufficiency, ambition, self-deprecation, and inquisitive desire (she looks at things very intently, yet sometimes bashfully looks away); Sebastian a dutiful, conflicted son as well as a lady (ostensibly genderfluid rather than trans), at times selfish or too caught up in his own need for safe hiding, at other times frank and courageous. Frances is willing to help Sebastian, and vice versa, because of mingled kindness, affection, and self-interest—and the willingness of each is tested. Both endure moments of terrible emotional exposure, betrayal, and bewilderment. Wang works the familiar turf beautifully. What I like best in The Prince and the Dressmaker is Wang's way with silence. Of the books 250-plus pages, almost a fifth are wholly wordless, and the great majority of spreads in the book include wordless panels or passages. The novel is entirely unnarrated, like a fast-moving film, but the delight Wang so clearly takes in rendering characters—and, my gosh, couture, in great, swooning, rapturous fits—roots the work in the pleasures of drawing and of comics. Some of the wordless passages dilate on brief sequences of action, catching and expanding small moments; others compress time, montage-style, whisking the characters through hours or days with giddy speed. The minimal wording and lavish drawing together convey ambiguous and conflicted emotion beautifully; witness pregnant moments of observation or reflection like this: The first example above seems, to me, to flirt with Frances's confusion about her own desires, or perhaps simply with the recognition of Sebastian's androgynous beauty. It says volumes. Both the first and second example show one of the things Wang is so very good at: emotional irresolution and the weight of the unspoken. Throughout the book, pairs of panels will hint at subtle interchanges and abashed feelings: All this happens against the backdrop of gorgeous pages, typically airy and free, generous with open space, against which panels and rows of panels appear to float. Bleeds are common: characters and scenes very often go right to the cut edge of the leaves (and implicitly beyond). Indeed Wang will often highlight a critical pause or loaded moment by placing a character at the bottom edge of the page so that the figure bleeds off, as if to hold the eye momentarily before the page turn. In any case, the pages are consistently dynamic without being attention-begging; Wang has a wonderful layout sense to complement her supple and expressive character drawings. No two pages are the same. I could go on about Wang's diverting artistry. It's the sort of thing I love to note: the kinetic freedom of her drawing; the exactness of the movements and expressions captured by her pencil and brush; the ravishing colors; the breath and pulse of the pages. But I think the things that really matter in The Prince and the Dressmaker are the narrative surprises and payoffs (er, these might qualify as spoilers, though I'll try to be vague): the cruelty of Sebastian's eventual exposure; the tender about-face that follows, upending cliched father-son dynamics; the delicious queering of a fashion show that serves as a sort of climax; and the final expression of the unexpressed that is, for me, the book's real climax. Of course all this is expertly cartooned, at the precise point where artistic discipline yields freedom. Yet it's Wang the total storyteller, the writer-artist, who finally gets to me. It's the complete package that made this jaded old reader daub his eyes. In sum, Wang has hit a new high. The Prince and the Dressmaker is very, very good comics, and puts the fairy tale tradition to wise ends. It envisions a better, braver world, one in which loving self-expression and artistic co-creation happily overleap ideological hurdles, setting more than one spirit free.

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed