|

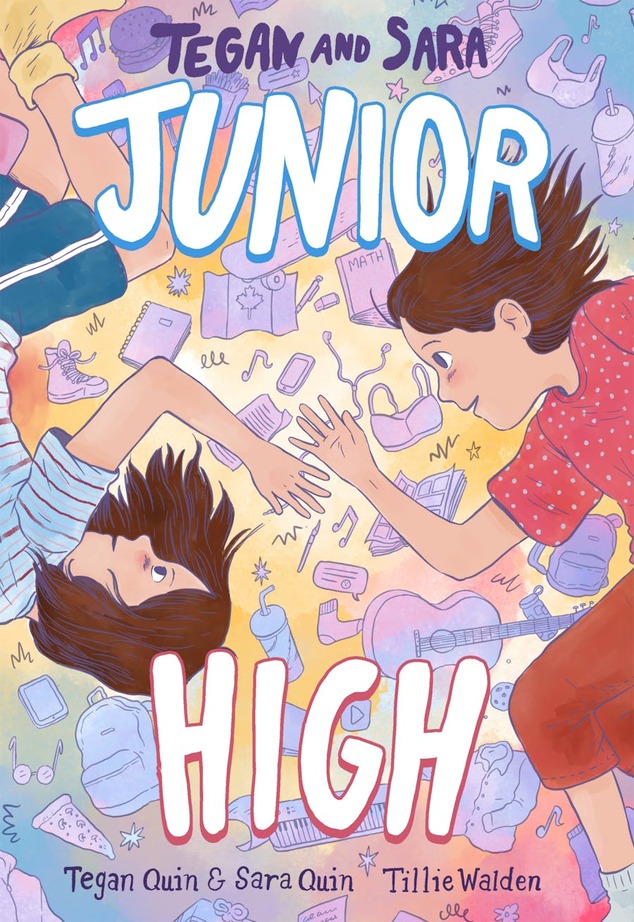

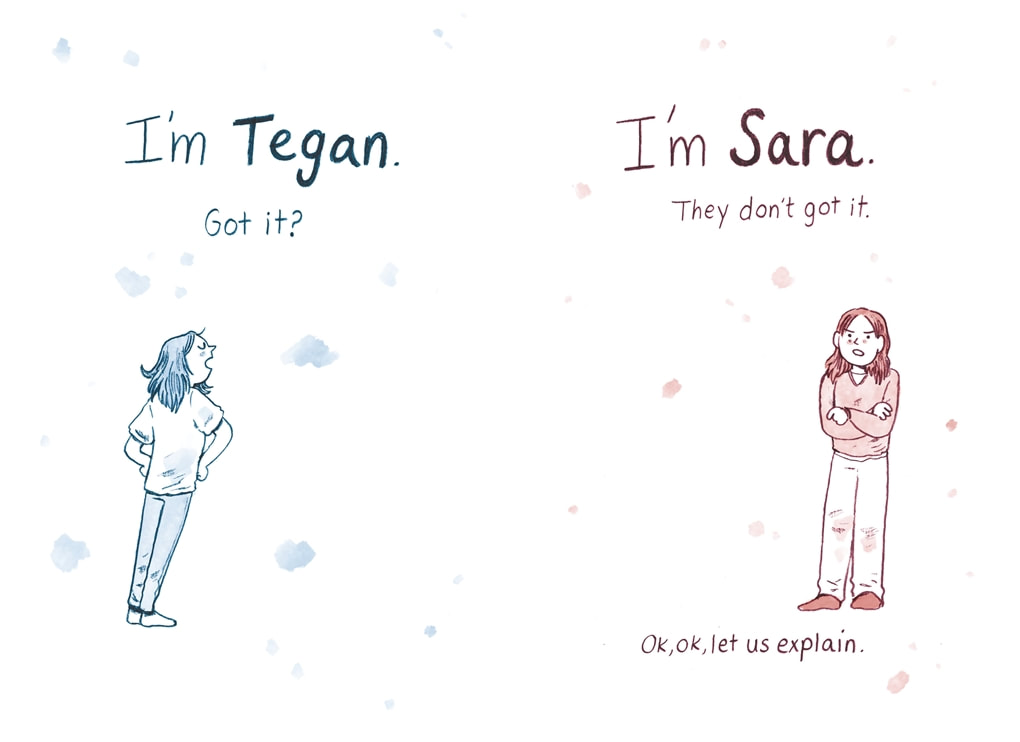

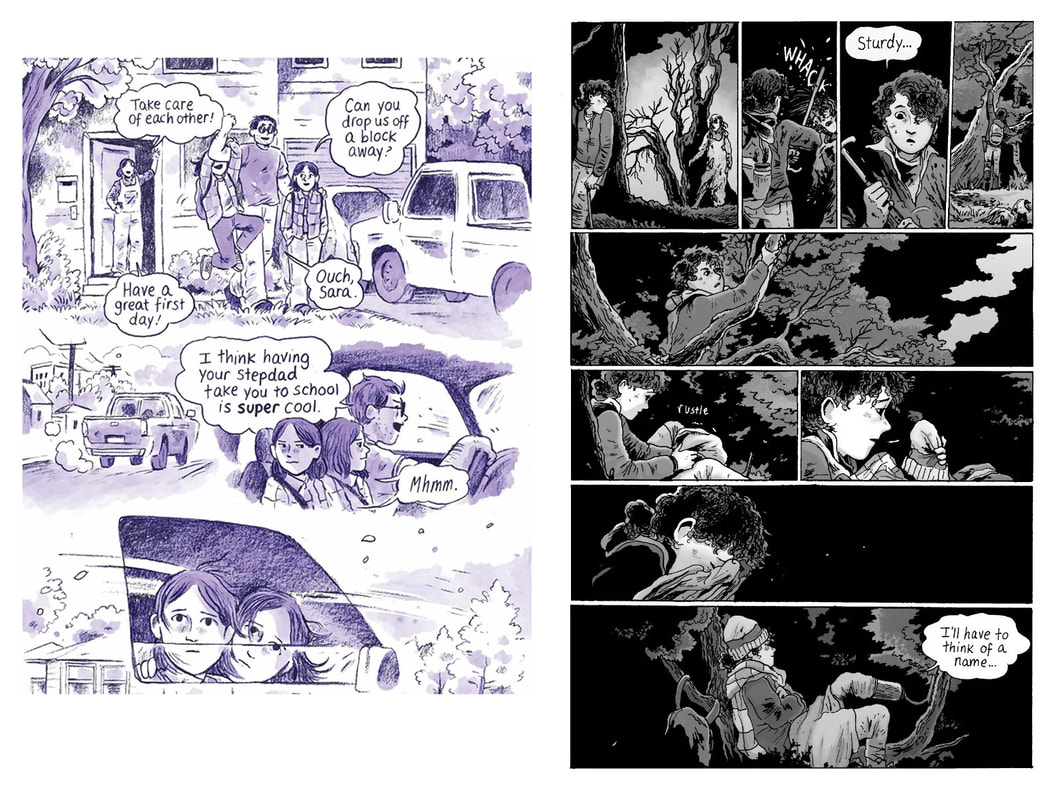

Junior High. By Tegan Quin and Sara Quin (scripting) and Tillie Walden (art). Farrar, Straus and Giroux, ISBN 978-0374313029, 2023. US$14.99. 304 pages, softcover. Tillie Walden strikes again! As ever, I'm excited to see a new book by Walden, one of America's most gifted comics artists and a particular favorite of KinderComics. I realize that this blend of fiction and autobiography (as the publisher calls it) is more likely to be billed as a true-to-life personal story by indie-pop stars and identical twins Tegan and Sara. Of course. Yet I have to admit that, for me, it began as a Tillie Walden book. It was Walden's name that got me to perk up and pay attention, and for that I'm glad. Turns out it's very well-written by Tegan and Sara, and yet another interesting departure for Walden. By now, Walden is hopefully no longer burdened with the wunderkind reputation that seemed to stick to her for her first several books. I mean, that rep was understandable — she was amazingly young for a graphic novelist, it seemed, and fearsomely prolific and good — but Walden has been productive and versatile for years, and is now a teacher at her old school, the Center for Cartoon Studies, so she's a veteran. And it does seem a bit foolish to keep marveling at how very much she has done in a short time. I'm still guilty of doing that, of course! What interests me now is the way she is departing from indy-comics expectations, branching out into different kinds of work. Since her last creator-owned graphic novel, Are You Listening? (2019), she has collected many of her early short works, co-created (with Emma Hunsinger) a collaborative picture book, undertaken a work-for-hire Walking Dead franchise series called Clementine, and now this, another collaborative work. Clementine is a trilogy in progress (the second volume is expected this fall), and Junior High promises to be the first half of a duology, so it looks as if Walden is dividing her work between different serial projects over a fairly long span. Huh. I would not have predicted these things a few years ago, but what do I know? Junior High is, we're told, a "lightly fictionalized" riff on the true story of Tegan and Sara Quin's first year in middle school, which in reality happened in 1991 but here is depicted in the present day, with all the cultural differences that that updating entails. For instance, cell phone use is near-constant here, and word balloons that represent texting are an important storytelling device. At one point (45), Taylor Swift fandom comes up in a conversation, but Swift was born when Tegan and Sara were nine! The Quins are upfront about the fact that the Tegan and Sara depicted here are "fictional" (an afterword explains some of the changes they made to their story). In essence, Junior High conveys the gist of junior-high experience circa 1991 in terms easily relatable to readers of that age in 2023. It's an interesting, if perhaps opportunistic, strategy. What matters is that the Quins write themselves and their schoolmates well, and Walden responds with graceful cartooning and beautiful pages. Briefly, the story follows the formerly inseparable twins into junior high, where their different desires and anxieties pull them apart, until their mutual discovery of music (via their stepdad's guitar, surreptitiously borrowed) brings them back together as a singing and songwriting team. Tegan and Sara are indeed hard to tell apart at a glance, and this becomes a running gag (even they sometimes confuse themselves with each other!). The two are pulled this way and that by budding social and romantic longings, with Sara crushing on one classmate, Roshini, and Tegan trying to win the approval of another, Noa, despite Noa's friendship with a bully who makes everyone feel lousy. Different forms of queer longing are gently explored, and milestones of puberty, such as the onset of periods and shopping for bras, complicate the social pressures the twins already feel. Much of the book concerns social maneuvering, the challenges of shuttling between different peer groups, the betrayal of confidences, and the awakening of desire. The writing is confident, the characterization observant and sensitive. What I love about Junior High is the delicacy that Walden brings to the story through her designs and drawing. The book is distinct from her earlier work, dispensing with framed panels and neat borders in favor of a more open, fluid aesthetic. The panels are separated by, not borderlines, but the deft use of negative space and patches of shading and color. This takes a little getting used to — the pages are still dense and busy — but only a little. Most of the story is colored only in shades of purple, recalling Walden's Spinning, but brief interludes — interchapters or pauses that punctuate the story — depict Tegan in blue and Sara in red, and drop the usual density of detail in favor of open layouts full of uncluttered white. These intervals allow the two sisters to reflect and unload in a symbolic space, underscoring their complex feelings. After Tegan and Sara discover songwriting together, Walden adds a vivid gold to the book's palette, bringing out the joys of music. I can't help but contrast Junior High with Walden's current project, Clementine, a survival horror series toned entirely in greys (by Cliff Rathburn of Walking Dead fame). The pages of Clementine, Book One, consist of tightly packed, sharply bordered panels, with layouts that grow increasingly jagged and dynamic as the story builds, leading to some manga-esque diagonals. The work is fittingly claustrophobic, combining Walden's familiar paneling with thick, atmospheric greyscales that match the story's muted horror, laconic storytelling, and emotionally stunned characters. With Junior High, Walden seems to be exercising different muscles, almost reinventing herself artistically. It's interesting to think about these two very different projects being on the boards at nearly the same time (especially coming after such disparate projects as Are You Listening? and My Parents Won't Stop Talking!, her collaboration with Hunsinger). I note that Junior High was drawn in pencil on watercolor paper, then colored digitally in Procreate, whereas Clementine was penciled in Procreate, then printed out and inked in pen on cardstock, so it appears that Walden is deliberately tacking back and forth between different methods. The penciled shading in Junior High opens up something new in Walden's art — and, as ever, I'm amazed at her hunger for growth and experimentation. In all, Junior High is a quiet joy: a smart, meticulously crafted adaptation, and another fascinating step for a wonderful cartoonist.

0 Comments

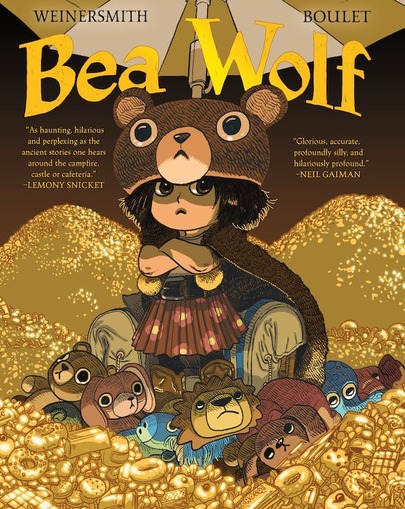

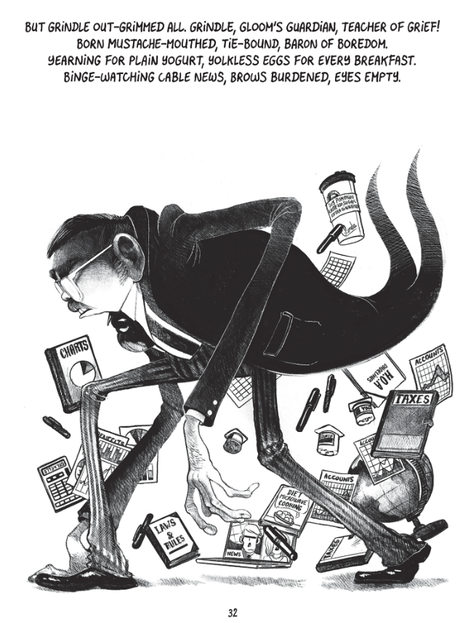

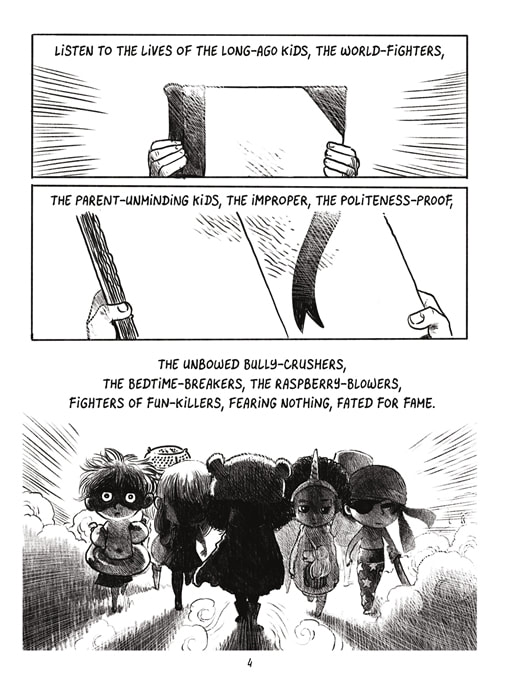

Bea Wolf. Written by Zach Weinersmith. Art by Boulet. First Second, ISBN 9781250776297, 2023. US$19.99. 256 pages, hardcover. Bea Wolf is brought to you by the same team that did the illustrated book Augie and the Green Knight some years back: Zach Weinersmith and Boulet. It's a graphically sumptuous retelling of Beowulf as a battle between rowdy, joyous kids and tedious, joy-sapping adults. Its proper soundtrack would be the number, "I Won't Grow Up," from the 1954 musical Peter Pan. That is, Bea Wolf assumes a world where kiddom is matter of keeping adulthood at bay. This raises the question of whether kids really want to continue being kids forever (a common fantasy among adults) or whether they want to, you know, gain more agency and autonomy in their lives. Bea Wolf has its cake and gobbles it too, depicting kids who have plenty of agency, of a fierce, ass-kicking kind, yet remain very much kids: big-eyed, neotenic, button-cute, and round. They're ruthless in claiming a certain kind of childhood: the kind that is all about performing irresponsibility, about waywardness, wildness, messiness, junk food binges, rude joke-telling, and wearing your underwear on your head. Their Grendel is "Mr. Grindle," a neighborhood Gradgrind who specializes in cleaning up, sanitizing, and disciplining, and in aging children with his deadly, withering touch. Of course, the kids have to fight him. Bea Wolf, then, is a celebration of childhood's anarchic side, even though, oddly, it features a kid "kingdom" with rulers and dynasties and national heroes. The "monster," in this case, is adulthood, and heroism consists of resisting it. There's a touch of Roald Dahl in all of this, and of course Peter Pan, and quite a bit else besides: familiar stuff. So, Bea Wolf is an elaborate, prolonged joke. Really, it's a bit of a soufflé, the sort of thing that needs to stay light and airy if it's going to work at all. Heaviness, ponderousness, would be deadly. The thing is, spoofing Beowulf usually does involve some heavy lifting. The language is technical and hard to ape; the world evoked is remote and strange. This is esoteric stuff by current children's book standards. Happily, Bea Wolf finds smart 21st-century analogs for the poem's beasts and heroes, and stays light enough to elicit chuckles from start to finish. I even laughed aloud at several points, early and late, which is unusual for me when reading a long comic. Part of what makes this work — for me, it may be the biggest part — is that Weinersmith is very good at parodying the "voice" of Beowulf: the rugged prosody, loping parataxis, alliterative phrasing, and vivid kennings of the old Old English. I mean, he does this hilariously well, from the start: The book has a firm voice, full of flavor, that stays the course despite the odd moment of deflation or comic anachronism (e.g., "Dawn rose, like a jerk"). Sometimes the verse rises to truly affecting poetry, like Bea's great last line on this page: Another thing that makes all this work — and I confess, this is what drew me to the book in the first place — is the cartooning of Boulet (Gilles Roussel). Boulet draws up a storm, makes the risible setting believable (enough), and transforms cliched, doll-like children into ferocious heroes. His digital renderings (drawn on iPad via Procreate) mimic the look of pencil and charcoal and brush, with, at times, a texturing so dense as to recall scratchboard — yet somehow he manages to maintain the necessary lightness and energy. Every spread is different, and many are quite elaborate. Layouts are dynamic, grids are avoided, and frame lines are using sparingly, so that each page-turn brings up another compositional treat. Man, he's good. In all, Bea Wolf is a charming book that may appeal most to lit nerd adults and the children who share their pleasures. Reading it feels a bit like playing an adult-centered but kid-styled game (Unstable Unicorns, maybe?). I dug it, and, er, I Iive in that kind of household. So, yay!

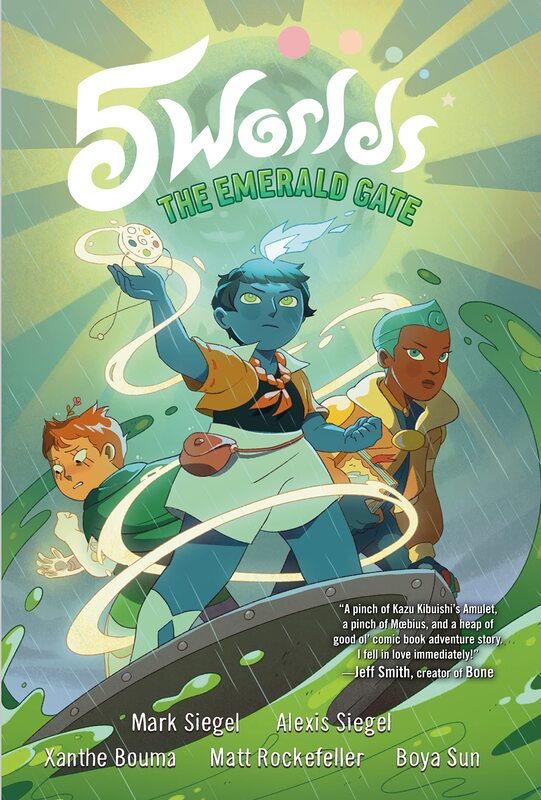

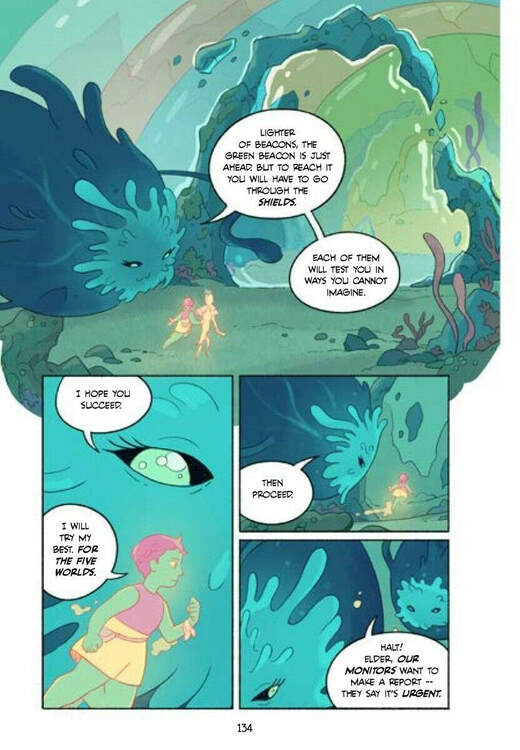

5 Worlds: The Emerald Gate. By Mark Siegel, Alexis Siegel, Xanthe Bouma, Matt Rockefeller, and Boya Sun. RH Graphic/Random House, 2021. The 5 Worlds series (five books set on five planets, published over roughly five years) has always been a high-wire act, balancing space fantasy, ecofiction, and Miyazaki-esque tropes with allegorical broadsides against neoliberalism and right-wing populism—all of this served up by a complex collaborative team consisting of five geographically dispersed co-creators. The way they have all worked together is a bit of a miracle. I’ve reviewed every volume (one, two, three, four) and keenly followed the evolving story of heroes Oona, An Tzu, and Jax and the many co-revolutionaries and loved ones they’ve gathered along the way. The series reaches it big finish with The Emerald Gate, and it’s a corker of a climax. Overall, the series has proved smart, bold, and very good—though I must admit it has left me with a sort of gnawing dissatisfaction, somehow. Pointedly allegorical from end to end, 5 Worlds has targeted egotism, greed, environmental carelessness, demagoguery, and (most clearly in Book 5) gradualism and hidebound deference to tradition, as its youthful heroes throw off the shackles of what has been done in favor of what can be done. The story is unabashedly progressive, topical, and on the nose. The Emerald Gate, dedicated to “the young people not waiting for permission to bring long overdue change to our world,” casts lead heroine Oona as a Greta Thunberg-like climate activist who must defy authority and take big risks to make big changes. The Five Worlds of the title are suffering a gradual ecocide—that is, dying of heat death—but an oily Trumpian oligarch (possessed by an ancient dark force) is trying his damnedest to smother that fact. Only drastic measures can save the day. This final volume’s signature phrase, Green doesn’t wait for permission to grow, signals Oona’s shift from diffidence to absolute certainty; she is done questioning, and now knows the way. Though the book takes time to sow little seeds of doubt (What if Oona’s plan only plays into the villain’s plan? What if the perfect solution turns out to be perfectly disastrous?), there really is no doubt: Oona and her fellow heroes must do something radical, must play for the highest stakes, if they are to save the Five Worlds. They must rebel. Oona must rebel. Above all, she must embody moral and political certitude. The Emerald Gate, more than its four predecessors, reveals an odd tension: between the radically egalitarian and democratic spirit to which the series aspires, and, on the other hand, the near-deification of Oona, the fated heroine who must give her all for the cause. In the home stretch, Oona undergoes a sort of ritual testing, running a gauntlet of five “filters” or “shields,” that is, moral and psychological trials, so that she can recognize “the truth.” Through this ritual, Oona rejects tradition and hierarchy, factionalism and rage, egocentrism, and personal desire. In effect, she rejects the novel’s version of neoliberalism. But this renunciation is the key to her final apotheosis; even as she rejects crude individualism, she is affirmed as The One who can channel the virtues and energies of all Five Worlds. While every member of Oona’s team plays a vital part in the novel’s ending, their final success depends on deferring to Oona’s vision and artistry (“Do not tell me your plan. I trust you”). In this way, the story uneasily mixes the political and the mythic—and remains, perhaps in spite of itself, a heroic fantasy in awe of individual gifts, somewhat at odds with its collectivist ethos. What makes all this work is that there is a price to pay. I won’t get into the details; suffice to say that Oona’s apotheosis entails a change of state and a goodbye—though also a sort of opening into ineffable new possibilities. Her transformations are so dramatic that she cannot return to ordinary life. Nor can she be quite understood. To resolve the story, Oona must escape the containment of the story, must step outside the frame her friends (and we readers) understand. Channeling the powers of the Five Worlds means being more than a person, and so there is lovely sense of consequence to the ending. What I’m talking about is not quite the wounded bittersweetness of Frodo Baggins at the end of The Lord of the Rings, but at least something that surprised me and made me reread the last few pages with care. The Emerald Gate well and truly finishes the story of Oona that began in 2017 with The Sand Dancer. I look forward to rereading this series all at one go. Aesthetically, it’s remarkably cohesive, a seamless collaboration despite the complex interworking it so clearly required. The Emerald Gate is (as I’ve come to expect) a sumptuous feast of worldbuilding and of deft, surehanded cartooning. The payoff in the end is rousing and full of feeling, enough to knock me for a loop. Overall, the book comes across as a paean to the indomitable spirit and visionary energy of the young—though this is one of those texts that, in my Children’s Literature classes, we’d be cross-examining to see what its construction of youth says about the hopes and needs of adults. While 5 Worlds depicts young people as radically free, it follows a didactic agenda that tries to teach young readers to be those free spirits, and to save us all. Ultimately, it rejects the shaded, tragically complex vision of one its avowed inspirations, Miyazaki, in favor of an unequivocal ending in which hesitation and gradualism can be identified with a hated Dark Lord and summarily banished. It’s all about the certainty of Truth. Yet the skeptic in me wants something a shade more tangled and complicated. In the end, I found myself wondering if the utopianism of 5 Worlds conflicts with some of the messages it has been trying so hard to convey. But, oh, what a rapturous five-year ride.

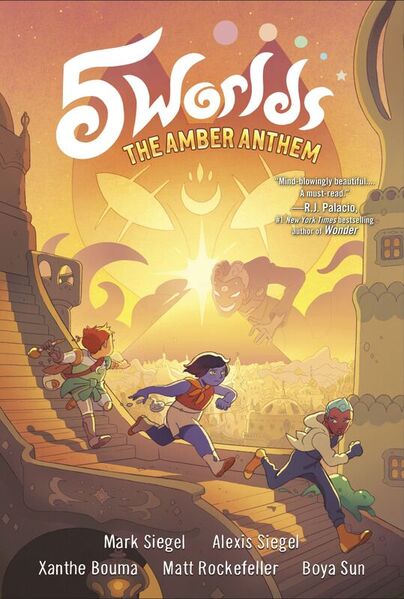

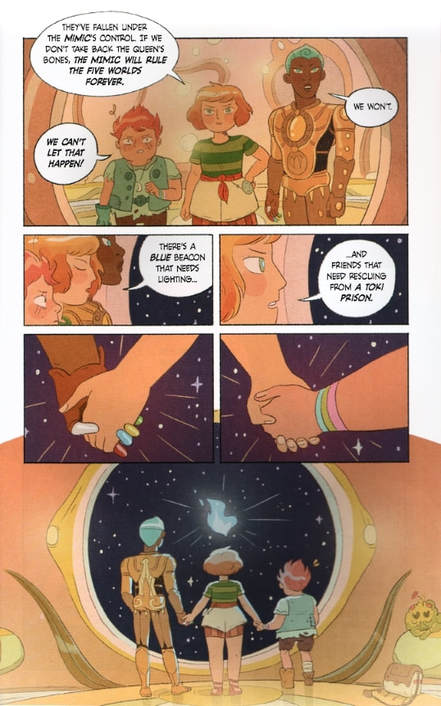

About eight weeks ago, I announced that KinderComics would be “taking a roughly six week-long break.” Every time I say something like that, I sigh—and sigh again when, eventually, tardily, KinderComics returns. So, okay, here I go again: Scheduling pressures under COVID, the endlessness of preparation and grading in my online teaching, and a looming sense that the world is going wrong, that it could explode any day—these things have been getting in my way. I admit I often consider closing this blog and moving on. Only reading and writing pleasure draws me back. So, let me switch gears and get down to the stuff that matters: 5 Worlds: The Red Maze. By Mark Siegel, Alexis Siegel, Xanthe Bouma, Matt Rockefeller, and Boya Sun. Random House, May 2020 Paperback: ISBN 978-0593120569, $12.99. Hardcover: ISBN 978-0593120552, $20.99. 240 pages. Who is the author of Five Worlds? This sprawling adventure series is the work of what seems to be an impossibly harmonious five-person team; somehow, the results comes across as the work of a single hand. Aesthetically, the series is gorgeous, a real feat of cartooning. Structurally, it’s tricky, with a modular, five-book shape, each book color-coded and focusing on a different world and different puzzle to solve (or secret to uncover, or McGuffin to find). Politically, it’s timely, with ever more obvious allegorical broadsides against Trumpism, neoliberalism, and xenophobia; in this progressive fantasy, world-building goes hand in hand with topical commentary that feels, as I’ve said before, on the nose. Alongside its familiar genre elements—the hype invokes Star Wars and Avatar: The Last Airbender as comparisons, but Miyazaki hovers over the whole thing too—Five Worlds conjures the anxieties of our times, and scores palpable hits against “fake news,” noxious right-wing media, climate change denial, and the shamelessness of greed-as-doctrine. KinderComics readers will know that I’ve been fairly obsessed with this series, reviewing Volumes One, Two, and Three in turn, and that I found the third, 2019’s The Red Maze, the most successful thus far at balancing genre convention, fresh discovery, and political relevance. With the latest volume, The Amber Anthem, the series has reached its fourth and penultimate act, and appears to be barreling toward a big finish. It’s actually a bit of a blur. In The Amber Anthem, the McGuffin is a song—the anthem of the title—and the story’s climax depends on thousands of voices lifted in song together, in a vision of peaceful yet powerful resistance that suggests real-world analogies: the Movement for Black Lives, and the recent surge in street protests despite COVID. (The book must have been written and drawn before that surge, and before the pandemic too, but its spirit of protest makes such analogies irresistible.) Here the dominant color is yellow, and the world is Salassandra, a planet briefly glimpsed before but now the center of the action. Our heroes, Oona, An Tzu, and Jax Amboy, once again seek to relight a long-quenched “beacon” in order to save the Five Worlds from heat death and environmental collapse. The Trumpian villain, Stan Moon—a host for the dreaded force known only as The Mimic—redoubles his attacks, even as Oona, An Tzu, and Jax take turns in the spotlight. The plot, as usual, is complicated, a tangled quest. Ordinary Salassandrans alternately help and hinder that quest (many having been persuaded that our heroes’ mission means ruin for the “economy,” and so on). The climax depends upon bringing together people of “five races.” Jax, a sports star, joined by a beloved pop singer, uses his celebrity to draw those people together—a handy metaphor for the way pop culture may provide opportunities for activism and community-building when official politics becomes hopelessly corrupt. Along the way, Anthem clears up several nagging mysteries, in particular the backstory of An Tzu (whose body has been, literally, fading away, book by book). I expected as much. Each new volume of Five World has delivered some big reveal or transformation for one of the heroes; now, with An Tzu’s history disclosed, the series seems poised for its finale. There’s a sense of unraveling complications here, yet of a tense windup at the same time. I confess that the big reveals here, though some of them came out of left field, didn’t leave me gaping or even happily stunned. Instead, I found myself jogging, not for the first time, to keep up with the frantic plot. Reveries and remembrances, sorties and missions, switchbacks and betrayals: it's a lot. The climax, though, is beatific: a shining vision of pluralism and collaboration and a lyrical evocation of “many strands…interweaving.” It's a triumphant close, but a corking good cliffhanger in the bargain, introducing a new moral dilemma and setting the stage what promises to be a breathless final volume. I’m keen—Five Worlds has been an annual stop for me, and I look forward to seeing how it all plays out. Five Worlds is a marvel of coordinated effort and cohesive design; again, its author-in-five-persons communicates like a single voice. Its world-building is lovely—I would happily pore through sketchbooks showing the collaborative process behind these books. That said, I’m starting to wonder whether the series’ complex rigging, breakneck plotting, and moral certainty are robbing it of some degree of complexity (as opposed to structural complicatedness, which it has in spades). The effect of Five Worlds on me, so far, has been like that of an action movie with soul, but its compression and momentum have not allowed for the sort of complex characterization that marks, say, Jeff Smith’s Bone, whose deepest characters, Rose Ben and Thorn, are sometimes at odds and go through hard changes. Five Worlds gestures toward the hard changes, and has enough soul to tend to the hearts and minds of its heroes, but everything feels a bit rushed. Despite the loveliness of the proceedings, then, at times the generic tropes come across as just that (Stan Moon, for example, speaks fluent Villain). When stories are ruthlessly streamlined, often what we remember are the clichés. I hope not. I look forward to the last chapter, The Emerald Gate, which I hope will bring everything—world-building, political urgency, and layered characterization—into balance one last, splendid time. When I open up the fifth and final volume, I’ll be holding my breath.

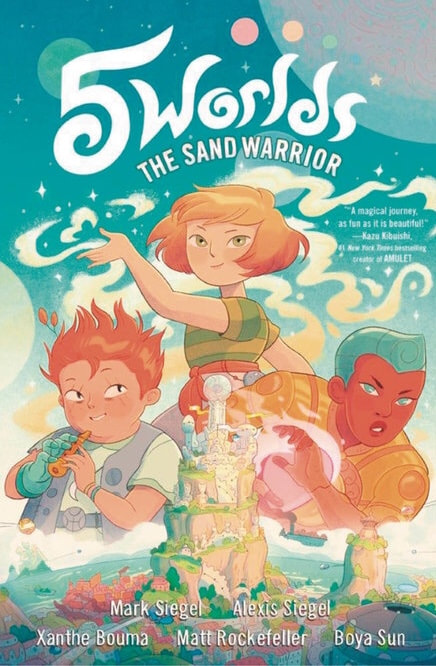

5 Worlds: The Sand Warrior. By Mark Siegel, Alexis Siegel, Xanthe Bouma, Matt Rockefeller, and Boya Sun. Random House, 2017. ISBN 978-1101935880. 256 pages, $16.99. A Junior Library Guild Selection. The Sand Warrior, a busy, fast-paced science fantasy adventure set in a wholly invented universe, teems with lovely ideas and designs. It is the first of a promised five-book series in the 5 Worlds (one book per world), and sets up a patchwork of different cultures, ecologies, technologies, and species. Indeed the book does some terrific world-building, the result of a complex collaborative process involving co-scriptwriters Mark Siegel and Alexis Siegel (brothers) and designer-illustrators Xanthe Bouma, Matt Rockefeller, and Boya Sun, working from an initial premise and designs by Mark Siegel. (Interestingly, Mark Siegel is founder and editorial director of First Second Books, but this is not a First Second title.) Reportedly, Mark Siegel conceived 5 Worlds as a project he would draw on his own (fans of Sailor Twain, To Dance, and his other books know that he could pull it off). However, as he and brother Alexis brainstormed the story, its plot and worlds grew so grand that he decided to turn it into a collaborative venture. Recruiting three recent graduates of the Maryland Institute College of Art — Bouma, Rockefeller, and Sun, who all met in a Character Design class at MICA — Siegel set in motion a complex, geographically dispersed teamwork, reportedly enabled by Google Drive, Skype or Zoom calls, texting, and secret Pinterest boards (see below for video links that shed light on this teamwork). The resulting book is remarkably consistent and aesthetically whole for such an elaborate process. It appears that Bouma, Rockefeller, and Sun became much more than hired illustrators on the project. They helped design and flesh out the worlds, and divided the page layouts and drawing (based on Mark Siegel’s thumbnails) in a selfless and seamless way. At the CALA festival last December, I bought a making-of zine (5W1 behind-the-scenes) from Bouma and Rockefeller, full of sketches and studies — a bit of archaeology for process geeks like me — and it intrigues me almost as much as the finished book. Visually, what has come out of that collaborative process is lovely. Story-wise, though, The Sand Warrior suffers from the greater ambitions of 5 Worlds. Its hectic, ricocheting plot zips forward too quickly for me to get a grip, even as it lurches into backstory with sudden, unexpected moments of info-dumping. Insertions here and there try to help the reader make sense of the 5 Worlds mythos (and do pay attention to the maps and legends on the endpapers). World-design and baiting-the-hook for future volumes get in the way of character development, even though the lead characters are soulful and troubled in promising ways. To be fair, there are moments of gravitas and emotional force amid the headlong action sequences, and there are consequential, irrevocable outcomes too. These impressed me. Yet I’d have liked to see longer spells of quietness, reflection, and clarity between the frenzied set pieces. The book actually does quietness rather well, but not enough; it has too much ground to cover. As a result, the plot comes off like a raw schematic of familiar things: prophecy, Chosen One, destiny, self-discovery, and reveals and reversals that I saw coming a long way off. When archetypal fantasy is stripped to its bones, too often the bones appear borrowed, and shopworn. It takes new textures to freshen those familiar elements. When the plot is streamlined to the point of frictionlessness (as in, for example, the breathless film adaptations of The Golden Compass and A Wrinkle in Time), we can all see that the game is rigged. My advice would be to slow down! Briefly, the plot of The Sand Warrior concerns the rival societies of five worlds: one great planet and her four satellites, each hosting a distinctly different culture. All five worlds are in crisis, dying of heat death and dehydration (a timely ecological allegory, ouch). According to an ancient prophecy, this catastrophe can be averted only by relighting the “Beacons” on each world, long since extinguished but still sources of wonder and controversy. Not everyone believes in this prophecy, and one world has plans of its own—prompted by the machinations of a dark, obscure adversary known only as the Mimic. Invasion and violence ensue. Our heroes, led by Oona, a mystically gifted yet diffident and halting “sand dancer,” seek to reignite the Beacon of their world and then defeat the Mimic. It’s all very complicated, with environmental and political workings and some of the plot machinery you'd expect to find in a fantasy epic with a prophesied hero. Bravely, The Sand Warrior tries to fill in all that detail on the fly; it foregoes the usual expository business of front-loading its mythos with a prologue, instead picking up backstory on the go. I appreciate that. However, this strategy poses challenges in terms of pacing and structure. Reading the book, I often felt as if I was being introduced to places and cultures just as they were being wrecked. The effect is like starting Harry Potter with the Battle of Hogwarts: too much too quickly, and with one or two familiar moves too many. By novel's end, even more interwoven secrets, and even more evidence of Oona's special nature, are hinted at—a touch too much—and the last pages almost desperately try to springboard into the coming second volume (out May 8). We close with obvious gestures toward self-realization and resolution but also toward open-endedness and further complication. Whew. Frankly, there’s too much to take in, and The Sand Warrior struggles to find a pace that is exciting but not skittish. Still, I look forward to further chapters in 5 Worlds. This five-headed collaborative beast, as frantic as its first outing may be, somehow has a single heart and speaks with a single voice. Sure, The Sand Warrior is overstuffed with known elements; the back matter acknowledges, among others, LeGuin, Bujold, and Moebius as inspirations, and many readers will also detect traces of Avatar: The Last Airbender and of Miyazaki (perhaps the beating heart of graphic fantasy nowadays). The story travels well-trod paths. But I like those paths; I like high fantasy. I also like the cultural complexity and diversity suggested by the book’s elaborate world-building. Further, the art attains a gorgeous fluency, with stunning color (reportedly Bouma did the key colors) and a lightness of touch, or delicacy of line, that recalls children’s bandes dessinées at their most ravishing. What’s more, the environments are transporting feats of design: giddy exercises in make-believe architecture and technology with a charming toy- or game-like density of detail. Naturally I want to stick around. I expect that The Sand Warrior will improve with rereading once more of 5 Worlds is revealed, and I look forward to seeing the characters through their troubles and gazing at whatever fresh landscapes they traverse along the way. In scope, and certainly in complexity of mythos, 5 Worlds compares well with Jeff Smith’s Bone — what it needs is patience, and pacing. Sources on the 5 Worlds Collaboration:

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed