|

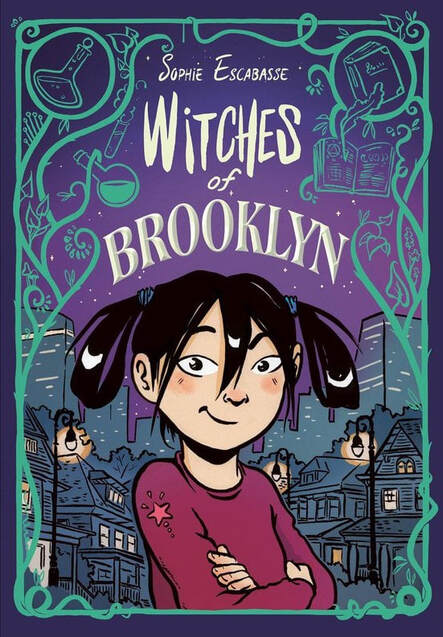

Witches of Brooklyn. By Sophie Escabasse. RH Graphic/Random House, 2020. ISBN 978-0593119273, $US12.99. 240 pages. In this middle-grade urban fantasy, the first in a planned trilogy, orphaned tween Effie is adopted by her eccentric aunts Selimene and Carlota, herbalists and acupuncturists who live in a quaint Victorian house in Flatbush. As it turns out, her aunts are also “miracle makers,” witches whose powers can bend reality and time—and Effie discovers that those powers run in the family. When a vaguely Taylor Swift-like pop star idolized by Effie runs afoul of some ancient magic and needs a cure, Selimene and Carlota take Effie into their confidence, and her training in magic begins. A clever, if rigged, story ensues, jammed with business, as Effie bonds with her aunts, makes friends at school, discovers the hazards of having power without knowledge, and becomes disillusioned with her former idol—but also saves her. The story abounds in Harry Potterisms and other well-worn tropes, and the frantic plot works against the bids for soulful characterization: for example, Effie begins as an embittered foster child with a chip on her shoulder, but then abruptly embraces living with her aunts, leaving all resentments and uncertainties aside. Hints of past unhappiness and family intrigue involving her late mother remain vague, perhaps foreshadowing sequels. There are plenty of loose ends. Author Sophie Escabasse’s style seesaws between joyous energy and fussy detailing. Her layouts are restless and dynamic, the traditional grids often enlivened by inset panels, frame breaks, and diagonals. There’s an enjoyable, exploratory quality about all this—the delight of seeing what a page can do—though the cluttered detail and overbusy coloring bog things down a bit. (On some pages, backgrounds are grayed out to bring the characters forward, which I think helps.) The characters are all distinct, with different silhouettes, head shapes, and faces—so different that they almost seem to have been drawn by different artists. Effie’s aunts are the most vividly realized and charming; in particular, Selimene, mercurial and feisty, stands out from the general busyness, with a comical design that recall Escabasse’s avowed influence André Franquin. Overall, Witches of Brooklyn strikes me as pretty good but also very familiar—so, I’m lukewarm toward it, despite its many good, smart moments. The sequels, I hope, will aim for less obvious plot-rigging, more rooted and consistent characterization, a sharper sense of what magic means and can do in this story-world, and, visually, not so much over-egging of the settings and details. As is, this first book crams in about three books’ worth of material and potential—I’d like to see Escabasse explore her world at a more deliberate pace. The second book reportedly will drop at the end of August.

0 Comments

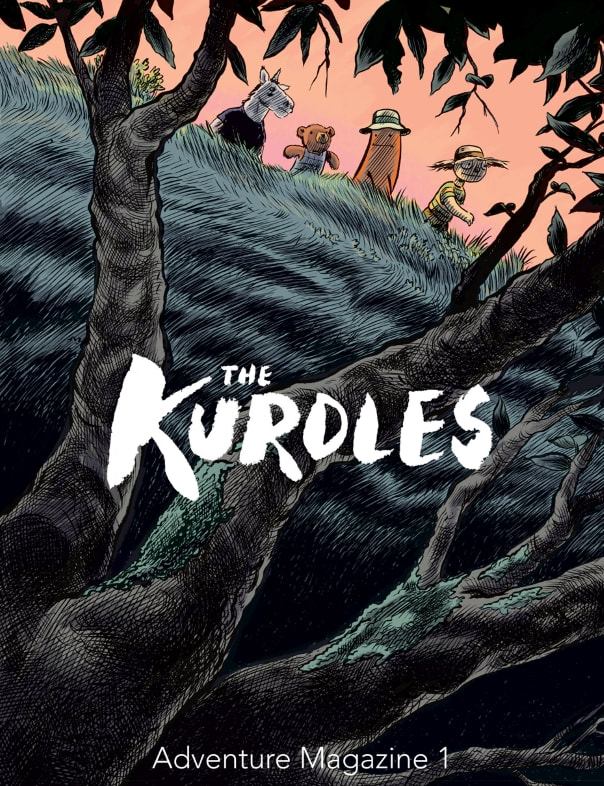

The Kurdles Adventure Magazine #1. Edited by Robert Goodin. Comics and other features by Robert Goodin, Andrew Brandou, Georgene Smith Goodin, Cathy Malkasian, and Cesar Spinoza. Fantagraphics, July 2018. 52 pages. The new Kurdles Adventure Magazine, brainchild of editor-cartoonist Robert Goodin, revisits the nonsensical world of Goodin’s graphic novel, The Kurdles (2015), with its eccentric characters, cockeyed story-logic, and gorgeous drawing. The Magazine’s 52 pages include half a dozen short stories and one-pagers starring the Kurdles (two of them reprints from anthologies) but also various stories and features by alumni of Goodin’s erstwhile micro-press venture, Robot Publishing: Cesar Spinoza, Andrew Brandou, and, probably the best known of the bunch, Cathy Malkasian (Percy Gloom, Eartha). These artists created deluxe minicomics for Robot back in the day, and generally hail from TV animation (Goodin’s day job, so to speak). The Magazine, then, not only carries on The Kurdles but also reaffirms Goodin’s bond with a small community of likeminded cartoonists. It’s a lovely, strange concoction that seems less like a children’s magazine, traditionally conceived, and more like an artist’s pet project. The Magazine offers new Pacho Clokey strips by Spinoza, a new Howdy Partner story by Brandou, and, strongest of the lot in my opinion, a lovely tale by Malkasian, “No-Body Likes You, Greta Grump.” It also offers, courtesy of Georgene Smith Goodin, a disarmingly complex set of directions for knitting one of the Kurdle characters, Pentapus (wow). Altogether, these features make for an odd, and defiantly uncommercial, mix. I found myself wondering who—besides me—this magazine is for. The Kurdles stories and pages here, Goodin’s, are sly and funny, reviving the quirky community of talking animals introduced in the graphic novel. Two of the stories, bookending the magazine, involve Sally the teddy bear (perhaps the series’s closest thing to a reader surrogate) asking questions about how color is perceived, and these become deliciously meta, in effect commenting on Goodin’s own choices as colorist and painter. These tales may bewilder readers unfamiliar with the graphic novel’s world, and are, well, pretty esoteric for first offerings from an “adventure magazine.” What can you say about a mag that begins with a story titled “Pentapus the Pentachromat”? In fact these stories didn’t quite “click” for me until I re-read the Kurdles graphic novel, and then re-read the stories—at which point their cleverness and characterizations made perfect sense. Readers who dig the Kurdles may wish for a much larger dose than what this first issue offers Malkasian’s “Greta Grump” concerns a mean, unhappy little girl who bullies a whole series of “rental” pets available at a pet shop until she finally meets her match in a blunt Seussian tortoise: a dapper, sharp-tongued Mr. Belvedere type who trades barb for barb and so bewilders the girl that he effectively disarms her. The relationship between Greta and “No-Body” is a tantalizing story engine, and Malkasian builds it with a light touch, avoiding didacticism even as she transforms Greta from a stock type, the little terror, into someone more shaded and interested. It’s a lovely, insinuating piece that has something to say about race (Greta is a white girl with parents of color who worries about not looking “like them”) but skirts the obvious moralisms, allowing its distinct comic twosome to get to know each other rather than worrying over the delivery of a Message. This is very promising work as well as a strong story in its own right. By contrast, Spinoza’s and Brandou’s contributions, though droll and distinctive, don’t seem to offer much in the way of future tales. When I reviewed the Kurdles graphic novel I marveled at its uncommercial and non-formulaic nature, its embrace of nonsense and defiance of conventional wisdoms. I suppose I have to say the same about this new venture. Goodin calls it an "independent, kid-friendly comic magazine," but frankly I can't see it working as a magazine in the traditional sense, and certainly not as a children's mag. Publication plans seem to call for just one issue a year, as the next issue is promised for summer 2019 (though perhaps the magazine is meant to speed up, once established?). Further, the first issue, while absorbing to this comics fan, does not offer a serial of the sort that the phrase “adventure magazine” brings to mind. Nor does it offer a succinct and enticing reintroduction to the world of Kurdles for those who have not read the graphic novel. While Fantagraphics is promoting this as the “best kids comic mag since the demise of Nickelodeon magazine,” it's really a world away from that model. The comics in it seem ripe for alt-comix anthologies of the Pood, Mome, or Now variety, rather than a mag that aims to be “kid-friendly” (though I'm not saying that the work is kid-unfriendly). The low frequency, lack of an anchoring serial (Goodin promises one starting in issue #2), and shortage of other interactive features besides comics (those knitting instructions do not strike me as kid-friendly) make The Kurdles seem like a long shot commercially, and I'm left to wonder if Goodin's Kurdles universe might best be served up in another venue, say in occasional issues of a more general comics anthology. Indeed the children's magazine format does not seem like the optimal vehicle for this work. Such a format needs to come out oftener, with a variety of appealing comics and non-comics features, such as activity pages, gag cartoons, and (I hate to say it) transmedia tie-ins. That’s what made the quirky comics section in Nickelodeon possible. Also, it should probably go without saying at this point that the direct market, which seems to be the primary market for this mag, is not the ideal matrix for a children's periodical. Despite some wonderfully eccentric comics, then--which will certainly lure me back for future issues—The Kurdles Adventure Magazine strikes me as a quixotic proposition at best. There's nothing wrong with that, but I do fear that the project will be hard to sustain without the kind of compromises that “kids' comic mags” usually entail. The Kurdles Adventure Magazine seems more likely to become an annual alternative comix booklet supported by diehards, as opposed to a kids' periodical with momentum, market presence, and a chance of making a dent in children's comics reading. Too bad, because a periodical with regular doses of Goodin and Malkasian is a wonderfully enticing prospect. Fantagraphics provided a digital review copy of this book. (Having seen it at last on paper, I have to say that the printed version wows me, color-wise. Paper suits Goodin's work!)

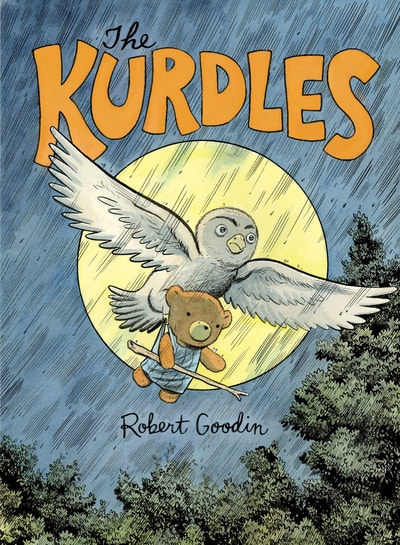

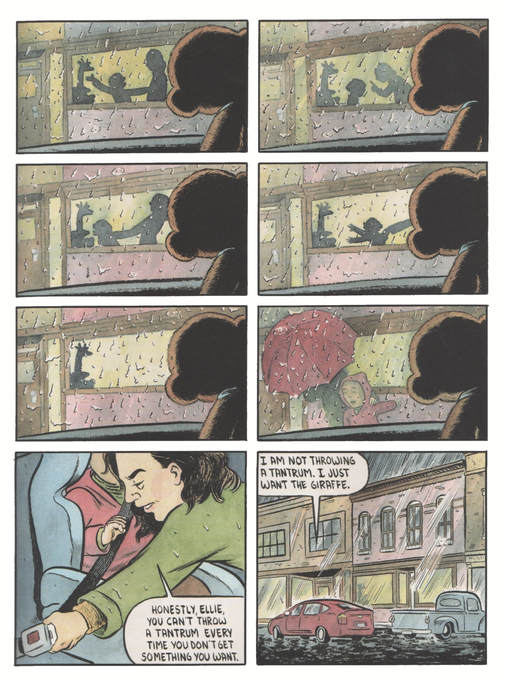

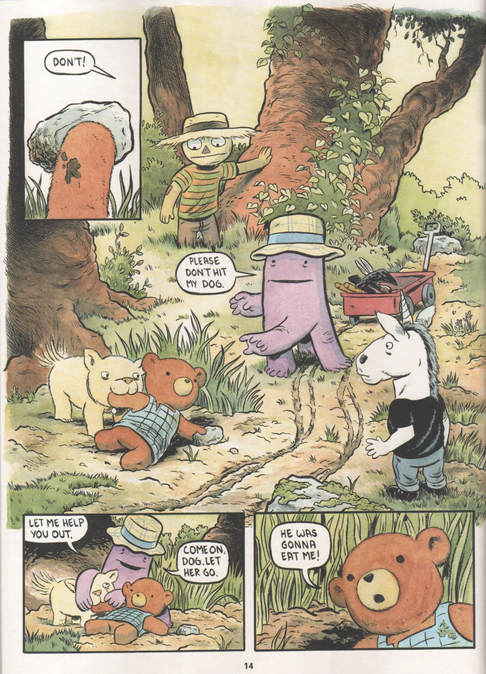

The Kurdles. By Robert Goodin. Fantagraphics, 2015. ISBN 978-1606998328. Hardcover, 60 pages, $24.99. A teddy bear gets lost, or discarded, by a child—that's how The Kurdles begins. Will she, Sally Bear, be reunited with "her" child"? The plot feints in that direction: a common story problem for child-centered, toys-come-to-life tales. Think Toy Story, and the nostalgia those films invoke: they're all about a kidcentric microcosm in which toys, though sentient, depend on the love of a child to give their life meaning. But The Kurdles doesn't end up telling that kind of story; instead it pulls a narrative bait-and-switch and becomes a sort of anti-Toy Story, one in which no Andy or Christopher Robin is needed to confer life or purpose on the lost teddy. Sally finds herself in Kurdleton, a woodland retreat, in the company of other critters: a land-going pentapus (think octopus with just five limbs), a unicorn in a tee shirt and jeans, and a scarecrow that evokes Baum's Oz (with perhaps a touch of Johnny Gruelle's Raggedy Andy too). This klatch of strange beasts also recalls, for me, Tove Jansson's Moominland, or Enid Blyton's Faraway Tree series. There's that same sense of utopian, slightly anarchic domestic community, of a little world apart from our own with its own matter-of-fact logic (or no governing logic at all). This is home to The Kurdles, and where the story wants to stay. With The Kurdles, then, cartoonist Robert Goodin has fashioned a fantasy world that owes a great deal to the history of children's books. Oddly, though, the book seems out of step with almost anyone's idea of a children's graphic novel today. The Kurdles does kids' comics the way, say, Gilbert Hernandez and co. did with Measles (1998-2001), or the way Jordan Crane did with The Clouds Above (2005)—that is, eccentrically, with seemingly no regard for the conventional wisdom about what today's children need or want. I suspect that's part of the reason why I like The Kurdles so much. Certainly I like this kind of idiosyncratic world-building in comics, regardless of intended audience. I expect that The Kurdles' best audience will be comics-lovers with a feel for the medium's history and an appetite for the upending of traditional story motifs. Me, I like it for the quirks and for the way it refuses to make sense. The book's opening depicts an argument between a human mother and child, as seen from a distance by a teddy bear. We don't yet know that the bear is Sally, or that she's alive: Sally's autonomous life is revealed only gradually, slyly, in the pages that follow, after she is parted from this human family. (The sequence in which she finally transitions from inert doll to living, moving creature is so delicious that I'm not going to show it here.) It takes even longer to reveal Sally's capacity for speech—which we realize about the same time as her capacity for self-defense, even violent resistance. What brings Sally fully to life is her arrival in Kurdleton, and the appearance of Kurdleton's other bizarre residents: What follows is a shaggy dog story in which a sickly house (the sum total of living quarters in Kurdleton) becomes anthropomorphic and then, as if delirious with flu, begins to sing sea shanties as if it were a drunken sailor. Yes, you read that right. The other denizens of Kurdleton set out to find a cure, but I'll say no more. Suffice to say that the Kurdles have no origin stories, no explanations for why they live in this place, nor any backstory that anyone feels obliged to ask about. Only Sally, of all the characters, has the rudiments of an "arc" (and even hers gets rerouted). What's more, the Kurdles don't have the familial structure of Jansson's Moomins, or the love of a human child, à la Milne's critters in the Hundred Acre Wood, to bring them together. They're just weird, and live in a weird place, where their essential weirdness needs no excuse. That's The Kurdles. The Kurdles is also eccentric visually. Lushly drawn and watercolored, it's organic, i.e. emphatically pre-digital, in look, with a fully realized, woodsy environment. Boldly brushed contours coexist with dense hatching, and the art is texture-mad. Color-wise, Goodin's pages depart from the Photoshop norm of most children's graphic books, and I found myself looking for the rough edges where linework and watercolor met (though Goodin is so crisp that I hardly ever found them). The work is old-fashioned and sumptuous, illustrative and humanly accessible to these middle-age eyes. Far from the clear-line, flat-color style so redolent of children's comics (the bright Colorforms look that bridges everything from Hergé to Gene Yang), The Kurdles is beautifully scruffy, or scruffily beautiful. It's as if Goodin, whose work I know mainly from TV animation and his erstwhile Robot Publishing venture, is determined to make The Kurdles a space of retreat from all of his other doings. The Kurdles is blithe, blunt, and unsentimental, sometimes startling, often deadpan-hilarious: a world and logic unto itself. I dig it. I do worry, though, about the commercial prospects for work like this, i.e. work that carries with it a wealth of history and memory but hails from outside of the children's publishing mainstream. This is the sort of work that has flourished fitfully here and there under the aegis of the direct market and within a small-press, underground aesthetic (I think for example of Neil the Horse, c. 1983-88, by Katherine Collins, formerly Arn Saba). Fantagraphics has announced a Kurdles Adventure Magazine for this summer, and reading more Kurdles would do me good, so I can only hope. This is too weird and wonderful a world to lie fallow. Fantagraphics provided a review copy of this book.

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed