|

Plain Jane and the Mermaid. By Vera Brosgol. Color by Alec Longstreth. First Second, ISBN 978-1250314857, May 2024. $US14.99. 368 pages, softcover. Vera Brosgol is one of my favorite artist-authors in the children's graphic novel field. She's back with a new book, her first graphic novel since 2018, and it's a doozy. Mind you, Brosgol has not been idle. These past six years, she has, by my count, written and illustrated two picture books, illustrated two more, and worked as head of story on the film Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio. Whew! I'm glad to have a new graphic novel by her. Plain Jane and the Mermaid is a feminist fairy tale about outward appearances versus inward self-worth. It's also an inventive, and occasionally spooky, phantasmagoria that takes place almost entirely underwater. Jane, a "plain" young woman of apparently few prospects, dives into the deepwater world of selkies, sea monsters, and mermaids in order to rescue (?) Peter, a mermaid-stolen man with whom she thinks she has fallen in love. She hardly knows the guy, but he is beautiful, and she has asked him to marry her. Marriage is Jane's one hope, because, as the last survivor of a household without a male heir, she is about to be turned out of her home by a distant and uncaring cousin: A mysterious crone magically grants Jane the ability to survive underwater, and so Jane takes off in pursuit of her hoped-for husband. In the meantime, Peter is wooed and pampered by a trio of mermaids, little suspecting what they may have in store for him. Things turn dark(er) when Peter learns what it is that mermaids actually do with humans, but meanwhile Jane develops a comical yet genuine friendship with a seal who turns out to be a selkie, and her plainness (if that's what it is) no longer matters. There are twists and surprises en route, and the story ends delightfully, with a sense that various dangling loose ends have been tied up, or tied together, in unexpected but apt ways. It's the kind of well-engineered book where nothing goes to waste, and small details glimpsed along the way turn out to be openings (or deepenings). Brosgol's story-world is cruel. Parents and peers judge and shame; rivals tease and bully. Plainness of face and stoutness of body are condemned. Appearances count, and mirrors are threats. Beautiful people get unearned perks and learn to rely on them, while ordinary, unlovely people are expected to scrape and crawl. Social outliers are sacrificed for the comfort of the socially advantaged. Women get the short end of most everything, and predation and hunger rule. Some readers may be taken aback by the harshness of this world, but to me it seems honest enough. Some may be alarmed by certain terrible comeuppances that are meted out. The story is tough. Moreover, some undersea scenes are scary, as when, on a sunken ship, corpses come groaning to life and close in on Jane, or when a giant anglerfish almost snaps her up in its jaws, or when a mermaid bares her teeth. Brosgol isn't scary in quite the same way as, say, Emily Carroll (whose take on mermaids is positively terrifying); she pushes only a little at what middle-grade books usually allow. But she does push. Me, I love these moments of risk-taking. Her graphic novels always play for keeps, and that wins me over. So, Plain Jane is a recognizable Vera Brosgol book. Yet Brosgol deserves credit for making each book look and feel a little different. Plain Jane doesn't look that much like Anya's Ghost or Be Prepared (they don't look that much like each other, either). This one feels a bit rawer in the rendering, I'm guessing deliberately, but at the same time uses a full color palette, courtesy of color artist Alec Longstreth — a great cartoonist in his own right, and a great graphic novel colorist. He does a lot of heavy lifting here. (It's a shame Longstreth's name isn't on the title page where it should be. Though the back matter reveals some of the coloring process, and Brosgol praises "Alec" effusively, you have to read the fine print to find his full name.) Despite surface changes in style, Plain Jane boasts Brosgol's usual distinctive character designs, expert timing, and gift for small shocks. This is clear, classic cartooning. The book is not the revelation that Anya's Ghost was, but it's thrilling. Its roughly 350 pages pass too quickly, a fierce, lovely dream. The final affirmation of Jane's self-worth is not surprising — in that sense, the book ends where most of us would want it to end — but the trip is full of little gemlike touches. Vera Brosgol really is a gift, you know?

0 Comments

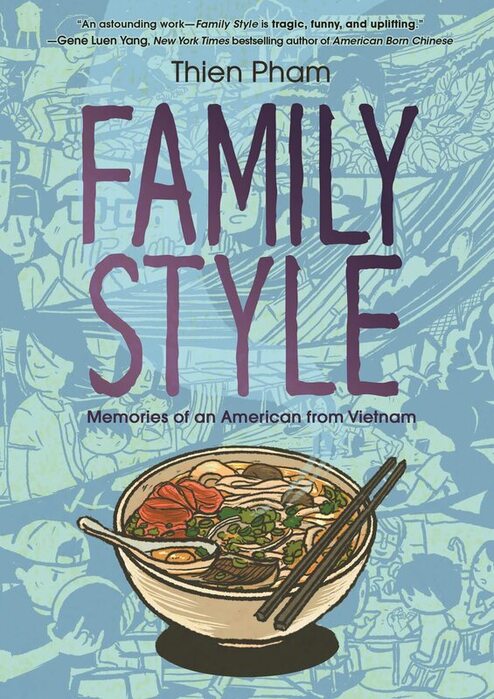

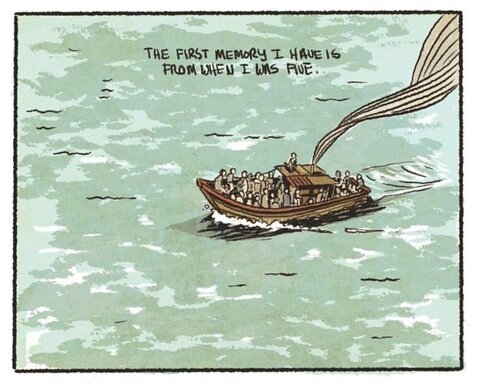

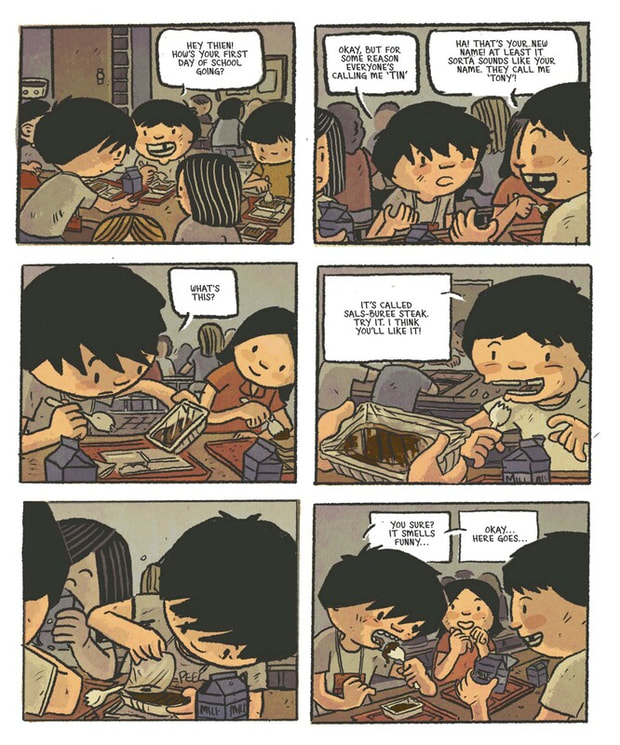

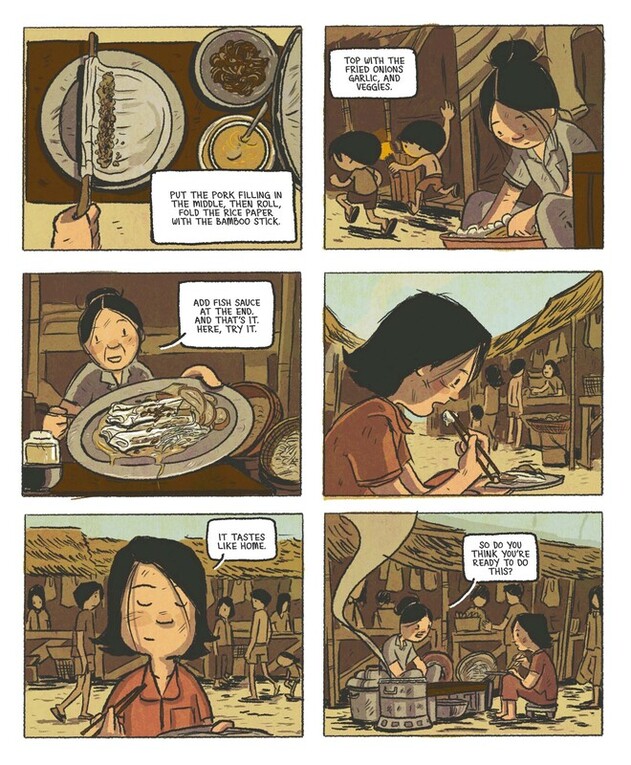

Family Style: Memories of an American from Vietnam. By Thien Pham. First Second, ISBN 978-1250809728, 2023. US$17.99. 240 pages, softcover. Family Style is a fast-moving, elliptical memoir that follows author Thien Pham from about age five to his early forties, starting with his family's emigration from Vietnam circa 1980 as refugees fleeing by sea, and ending with him as a high school teacher in the Bay Area circa 2016, around the end of the Obama presidency — the moment Thien belatedly becomes a US citizen. Through eight chapters, each running roughly twenty to forty pages, Pham follows his and his family's acculturation to the US. Every chapter is titled for a memorable meal, from rice and fish to bánh cuốn and so on, as befits Pham's reputation as a foodie cartoonist/columnist. Each captures a brief snapshot, a moment in time. The early chapters seem to form a smooth continuity, one flowing into the next without pause, but later chapters skip forward abruptly: for example, Chapter 6 depicts him as an elementary student in the mid 1980s, Chapter 7 has him as an adolescent in the late 80s, and Chapter 8 leaps forward roughly twenty-five years. Pham presents the story sans narration, so there is no knowing voice to guide us; we have to pay attention to understand how much time is passing and how Thien is changing. Chapter 5 shows young Thien learning some of his first English words, while Chapter 6 suggests that he has already begun to lose fluency in Vietnamese; Chapter 7 shows him consciously struggling with his in-between status as a somewhat assimilated American teen who is "kinda scared to hang out with other Vietnamese kids" (176). There's an awful lot going on, if you read closely. Pham's fast-moving story is aided by a measured and understated aesthetic that takes everything in stride. Originally published serially to Instagram, Family Style is a blinking narrative, a series of flashes knit together by a steady layout. The pages consist mostly of regular six-panel (3x2) grids, punctuated by occasional single-panel splash pages that bleed out to the book's edge. Pham renders everything in a roughhewn style, with drastically schematized cartoon faces. His digital drawings (created with Procreate on an iPad) are strikingly organic, flecked and a bit scratchy and colored with a muted palette in which colors and tones have a grain and rawness that seems positively earthy. It looks terrific and reads even better. As in the best cartooning, Pham attains a seeming simplicity through complex means — again, if you look closely, there's a lot happening. Some of the most telling details are faraway or half-buried in the mix, waiting to be discovered and puzzled over. Though Family Style begins with harrowing suggestions of violence (only half-glimpsed through a child's eyes), it is really an optimistic, affirming book. Pham is remarkably gracious and funny even as he tells of losses and little betrayals. The story implies the pressure to assimilate and captures Thien's adolescent uneasiness as a cultural outsider or recent arrival, and many little incidents in the book seem sad (for instance, Thien throwing away homemade bánh cuốn so that he can eat Dairy Queen burgers with his mostly White buddies). In this sense, the book is terribly open and revealing. Yet Family Style is quite positive about Pham's process of becoming an American, including the hurdles to citizenship (so, the book's subtitle seems deliberate). Also, Pham's "endnotes," in the form of charming strips about sources and creative process, comically depict him interacting with his parents, who come across as amused informants — lending the book's conclusion a cheerful, settled tone. Even Pham's depictions of privation, as in Chapter 2's patient recreation of life in a Thai refugee camp, are shot through with happy recollections of minor details: a children's game, a small, ingenious life hack, or his mother's unflagging resourcefulness. I'm considering teaching Family Style this fall alongside Thi Bui's celebrated The Best We Could Do, another graphic memoir of Vietnamese American experience (and one I've taught a lot). My reasoning has less to do with commonalities than with differences. In fact, the two books are strikingly unalike. Whereas Bui builds her story alinearly and recursively, moving fluidly from present to past, Pham works in something closer to a straight line. Whereas Bui narrates reflectively, Pham simply shows. Bui excavates family history and recounts Vietnam's decolonization, while Pham concentrates on what he would have seen firsthand. Pham's book is much shorter, and uses a regular layout and blocky cartoon aesthetic in contrast to Bui's dynamic pages and fluid brush inking. Finally, The Best We Could Do is melancholy, introspective, and ambivalent, but Family Style is comparatively high-spirited, even playful (though it hints powerfully at loss and dislocation along the way). What the two have in common is that they are simply great comics. Pham has said that he'd like to follow Family Style with a story about traveling back to Vietnam and recovering family history there. I would happily read that.

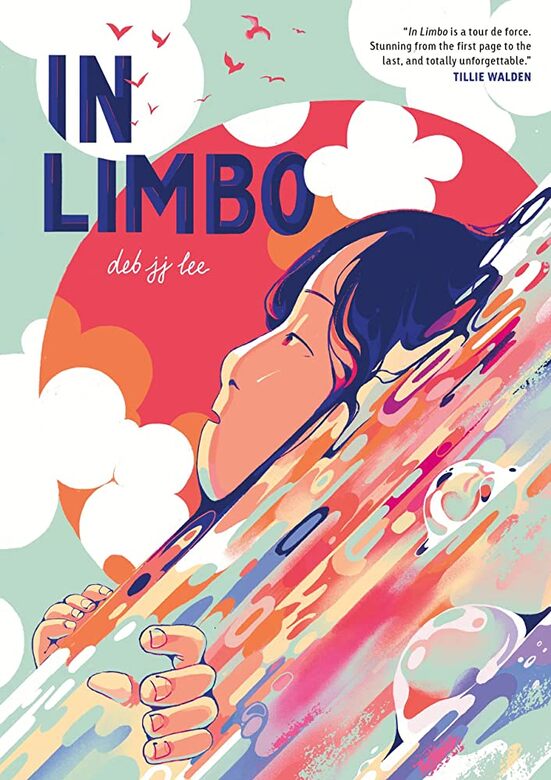

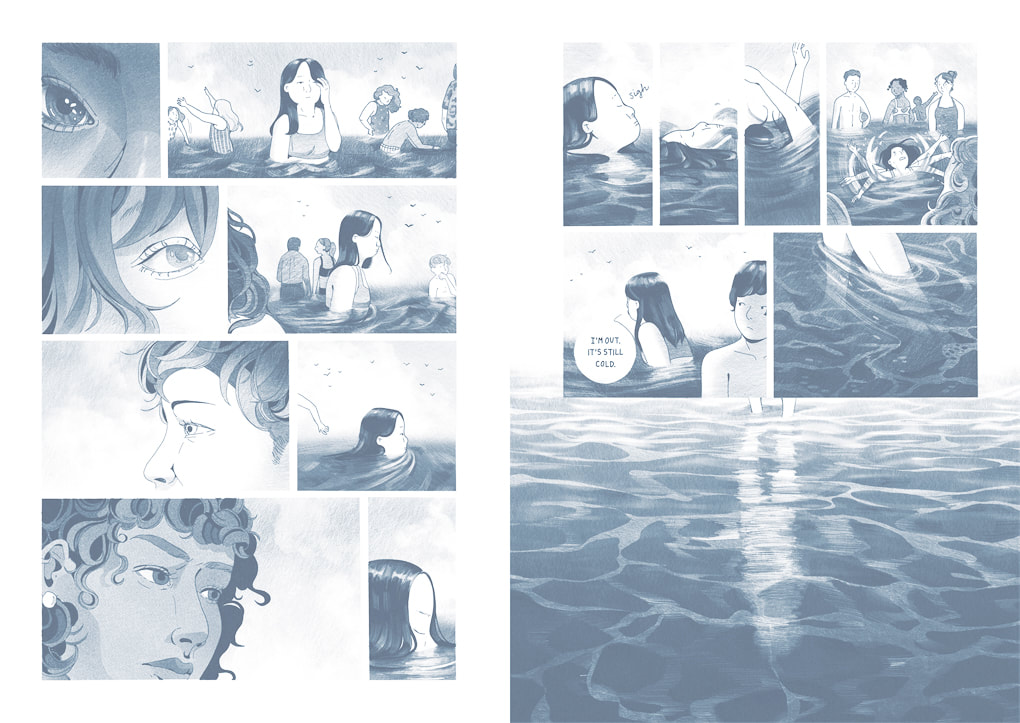

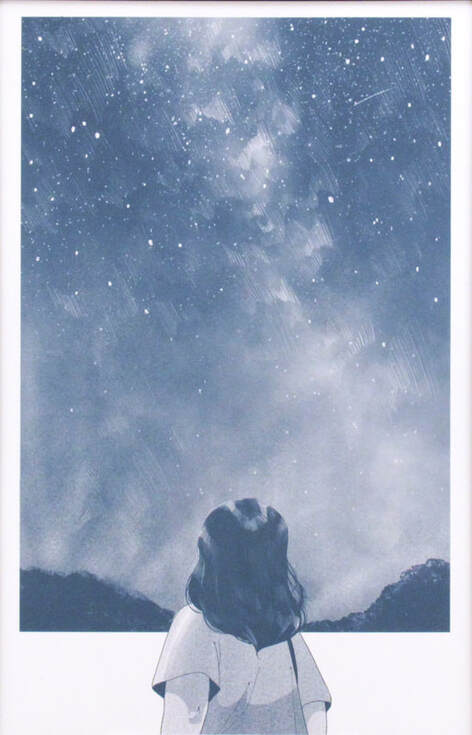

In Limbo. By Deb JJ Lee. First Second, ISBN 978-1250252661, 2023. US$17.99. 352 pages, softcover. I lost sleep over In Limbo. Foolishly, I started to read it late one night, when I was in a sticky, sort of unhappy mood that had nothing to do with the book and much to do with work. I needed to read something that was utterly different than the work I was obsessing over; I needed a way out of my spiraling. So, I thought I would start In Limbo before bed. Just start it, you know? Get my feet wet. But no — once I started, I had to finish. Damn. There was something quietly harrowing about the book, something that frustrated and gnawed at me. I think maybe I was angry with the book's protagonist, and her mother? Or maybe bothered by the evocations of racism, bullying, or depression? Struck by the contrast between the book's elegant, quiet style and its dark undertow? Whatever it was that got to me, I felt pretty helpless about it. I mean, I did put the book down for a few minutes, about a third of the way in, but then I grabbed it up again, anxiously, and plowed on. As the story got deeper and darker, I was all in. When I finished, it was well after midnight — and of course I had the story on my mind as I tried to get some shuteye. Again, damn. In Limbo is a graceful and refined graphic book, a beautiful feat of design, and a moody, enveloping story. It's also observant and brave. Thematically, the book treads some familiar ground: a high school memoir; a Korean immigrant's story; an exploration of familial tensions, crushed friendships, cultural in-betweenness, mental and emotional fragility, suicidal thoughts. The protagonist is a version of author Deb JJ Lee, and the story tracks her four years of high school, leading up to graduation and college after a long spell of desperation and loneliness. Okay, none of that feels unprecedented. But In Limbo is bothersome and riveting, a tough, involving work. I couldn't read it complacently. It pulled me in with its long silences, layered, emotionally telling details, fraught conversations, and occasional shocks. Its cloudy, blue-grey palette, monochrome yet somehow endlessly varied, feels soft, yet Lee uses it to create sharp, crisply defined pages — despite their refusal of black frame lines and their frequent use of bleeds. (Note that in life the author goes by they, but the book genders Deb as she, which, Lee says, more accurately reflects who they thought they were in high school.) Their layouts are often dense and maximally detailed, yet the overall impression is dreamlike, entranced. At first blush, it looks like a book that should be calm. But calm is not what the book is about, and reading it often hurts. What I'm trying to say is, this is a great and hard book. Briefly, In Limbo follows Deborah (Jung-Jin), or Deb, through her four years of high school as she tries to love and understand herself, embrace art as her vocation, and get out from under her family's expectations, especially the relentless needling of her very driven, at times abusive, mother. Her mom, as a character, hews perilously close to the "tiger mom" stereotype (as the book itself acknowledges). Their relationship is full of jagged edges and cruel scenes — and it's one of the things, I think, that caused me to read on, after midnight, in hopes of relief or understanding. Deb's father and brother don't register as strongly; In Limbo is very much a daughter/mother story. Yet it's also about friendships, sometimes fraught, overburdened ones. Deb's feelings for her friend Quinn, to whom she has a sort of desperate, proprietary attachment, lead to surprising reversals. Officially, In Limbo is described as "a cross section of the Korean-American diaspora and mental health," and that seems right, but it is Lee's depiction of complicated, ambivalent relationships that yields the greatest shocks. Lee doesn't show young Deborah as a good friend; instead, they show her taking friends for granted, or reading them strictly through the lens of her own anxiety, or laying terrible responsibilities on them. In this sense, the book seems self-accusatory. Deb doesn't understand what she's doing, of course, and the story is partly about her coming to grips with how she hurts both her friends and herself. Some relationships outlive the end of the book, others don't, but the book is remarkably generous in the home stretch, as Deb opens out from the tortured inwardness of the first half and learns to see more clearly. To say that the book's characterizations are complex would be a measly understatement. In Limbo doesn't resolve every problem it raises. This is probably partly by design; Lee has acknowledged in interviews (again, see this one) that their life, past and present, is more complex than a single book can cover, and the book seems anxious to show Deborah as a work always in progress. There are things in the book I'd have liked to know more about. Some relationships and threads are still nagging me, even now. Some readers may finish the book wanting to know more about Lee's understanding of internalized racism and the pressure to assimilate. Some may wonder about the connection between those things and the book's tormented mother/daughter dyad (cf. Robin Ha's graphic memoir Almost American Girl). Some readers may be anxious to know more about the mother's abuse, what prompts it, and how Deb lives with it (cf. Lee's own short comic from 2019, "Dear CPS," readable on their website). Some may wish that the Künstlerroman aspect of the book came through more strongly, that they were left knowing more about Deb's artistic vocation. Some may wonder about Deb's implicit queerness or perhaps about gender nonconformity. I've been thinking about all those questions; the book feels a bit tentative about what to include, what to leave out, and how to balance things. That said, I don't expect complete "closure" in memoir, and when I do get it, I worry that I'm being sold a bill of goods. In Limbo has honesty and emotional rawness despite its delicately finished surface, and I dig that. That "surface" is going to draw in and mesmerize a lot of readers, I expect. The book's rapturous reception has a lot to do with Lee's virtuosity as an illustrator and designer (indeed, the many blurbs on the cover note their lush, meticulous art). In Limbo is visually extraordinary; the book is gorgeous and transporting, a master class in narrative drawing and sustained mood. That mood is melancholy almost the whole way through, but In Limbo is vital and ravishing enough to make one fall in love with melancholy. (My images here don't do the book justice.) I'm grateful to this book for introducing me to a singular and gutsy artist. Most highly recommended: another high watermark for autobiographical comics about adolescence. <3

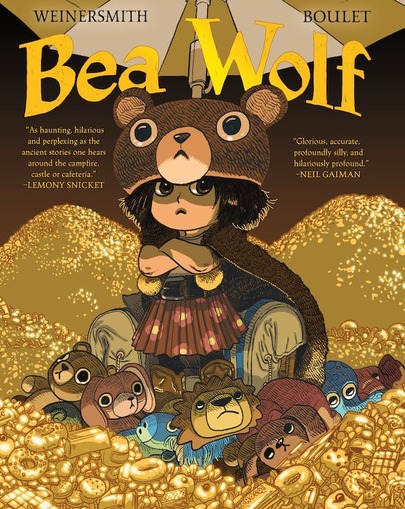

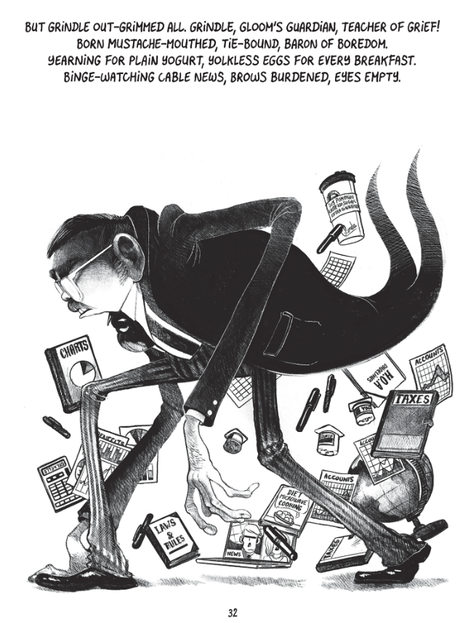

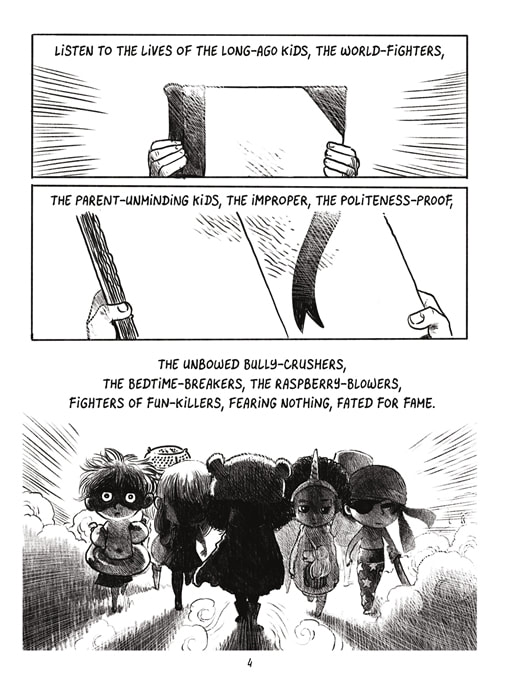

Bea Wolf. Written by Zach Weinersmith. Art by Boulet. First Second, ISBN 9781250776297, 2023. US$19.99. 256 pages, hardcover. Bea Wolf is brought to you by the same team that did the illustrated book Augie and the Green Knight some years back: Zach Weinersmith and Boulet. It's a graphically sumptuous retelling of Beowulf as a battle between rowdy, joyous kids and tedious, joy-sapping adults. Its proper soundtrack would be the number, "I Won't Grow Up," from the 1954 musical Peter Pan. That is, Bea Wolf assumes a world where kiddom is matter of keeping adulthood at bay. This raises the question of whether kids really want to continue being kids forever (a common fantasy among adults) or whether they want to, you know, gain more agency and autonomy in their lives. Bea Wolf has its cake and gobbles it too, depicting kids who have plenty of agency, of a fierce, ass-kicking kind, yet remain very much kids: big-eyed, neotenic, button-cute, and round. They're ruthless in claiming a certain kind of childhood: the kind that is all about performing irresponsibility, about waywardness, wildness, messiness, junk food binges, rude joke-telling, and wearing your underwear on your head. Their Grendel is "Mr. Grindle," a neighborhood Gradgrind who specializes in cleaning up, sanitizing, and disciplining, and in aging children with his deadly, withering touch. Of course, the kids have to fight him. Bea Wolf, then, is a celebration of childhood's anarchic side, even though, oddly, it features a kid "kingdom" with rulers and dynasties and national heroes. The "monster," in this case, is adulthood, and heroism consists of resisting it. There's a touch of Roald Dahl in all of this, and of course Peter Pan, and quite a bit else besides: familiar stuff. So, Bea Wolf is an elaborate, prolonged joke. Really, it's a bit of a soufflé, the sort of thing that needs to stay light and airy if it's going to work at all. Heaviness, ponderousness, would be deadly. The thing is, spoofing Beowulf usually does involve some heavy lifting. The language is technical and hard to ape; the world evoked is remote and strange. This is esoteric stuff by current children's book standards. Happily, Bea Wolf finds smart 21st-century analogs for the poem's beasts and heroes, and stays light enough to elicit chuckles from start to finish. I even laughed aloud at several points, early and late, which is unusual for me when reading a long comic. Part of what makes this work — for me, it may be the biggest part — is that Weinersmith is very good at parodying the "voice" of Beowulf: the rugged prosody, loping parataxis, alliterative phrasing, and vivid kennings of the old Old English. I mean, he does this hilariously well, from the start: The book has a firm voice, full of flavor, that stays the course despite the odd moment of deflation or comic anachronism (e.g., "Dawn rose, like a jerk"). Sometimes the verse rises to truly affecting poetry, like Bea's great last line on this page: Another thing that makes all this work — and I confess, this is what drew me to the book in the first place — is the cartooning of Boulet (Gilles Roussel). Boulet draws up a storm, makes the risible setting believable (enough), and transforms cliched, doll-like children into ferocious heroes. His digital renderings (drawn on iPad via Procreate) mimic the look of pencil and charcoal and brush, with, at times, a texturing so dense as to recall scratchboard — yet somehow he manages to maintain the necessary lightness and energy. Every spread is different, and many are quite elaborate. Layouts are dynamic, grids are avoided, and frame lines are using sparingly, so that each page-turn brings up another compositional treat. Man, he's good. In all, Bea Wolf is a charming book that may appeal most to lit nerd adults and the children who share their pleasures. Reading it feels a bit like playing an adult-centered but kid-styled game (Unstable Unicorns, maybe?). I dug it, and, er, I Iive in that kind of household. So, yay!

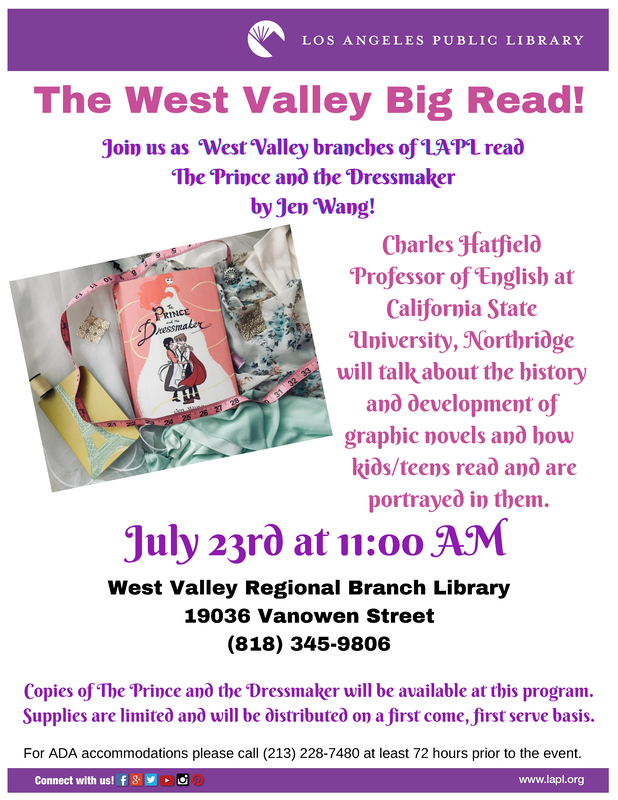

I'm honored and delighted to be giving a talk as part of the Los Angeles Public Library's West Valley Big Read focusing on Jen Wang's graphic novel, The Prince and the Dressmaker (the first book I ever reviewed here on KinderComics). Jen Wang is one of my favorite cartoonists, and The Prince and the Dressmaker one of my favorite books of the 2010s. In fact, I'd say it's one of my top ten graphic novels of the past half-decade. So doing this talk is a real treat! As the above flyer says, the talk is happening at the West Valley Regional Branch Library on Saturday, July 23, at 11:00 a.m. LAPL has more information about the talk here: https://www.lapl.org/whats-on/events/lets-talk-graphic-novels. Readers, I hope some of you will be able to make it — and please help spread the word!

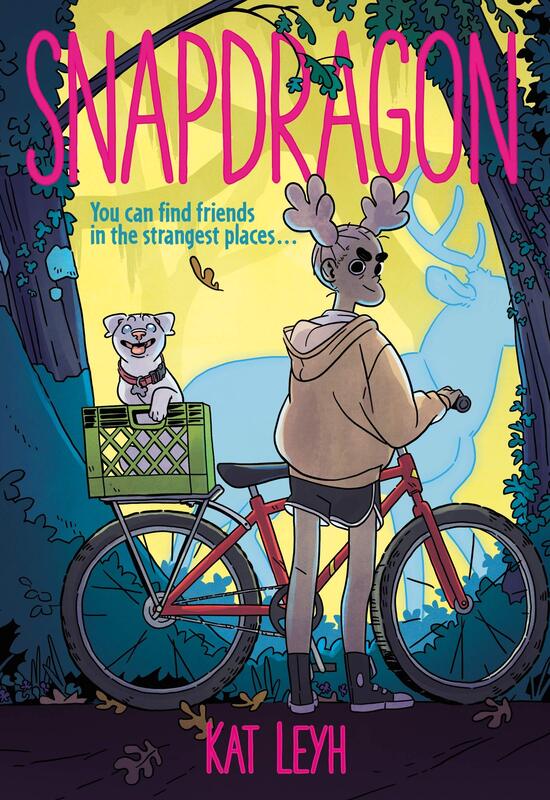

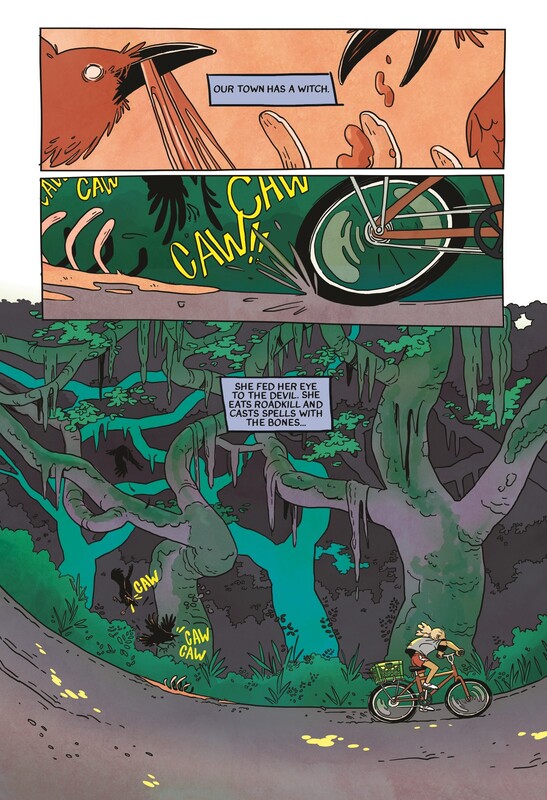

Snapdragon. By Kat Leyh. First Second, 2020. ISBN 978-1250171115, $US12.99. 240 pages. I favored Snapdragon to win this year’s Eisner Award for Best Publication for Kids (though, um, another book ended up winning). Of all the recent comics about witches that I’ve reviewed here, Snapdragon strikes me as the most sure-handed and persuasive, as well as the richest. It shares with most of the other “witch” books a progressive, inclusive, queer-positive ethos and Bildungsroman structure. Snapdragon, though, brings even more to the table, without ever overcramming or pushing too hard. Unsurprisingly, the book has a utopian, welcoming, vibe, but author Kat Leyh stirs in so much complicated humanness that the results never seem pollyannish or schematic. What we get is a winningly complex cast of characters, queer and trans representation that is central to the story while being gloriously unflustered and direct, spooky supernatural details that resolve into unexpected affirmations, and, above all, vivid and confident cartooning – one terrific, nuanced page after another. I was just a few pages in when I realized that I was in the hands of a master comics artist. The book has guts. Its first panel delivers a closeup of hungry birds tearing into carrion (roadkill), then zooms out to Snapdragon, or Snap, barreling through the woods on her bike. “Our town has a witch,” Snap’s opening captions tell us. “She fed her eye to the devil. She eats roadkill. And casts spells with the bones…” So, by way of opening, Leyh leans into the creep factor: But Snap, a fierce young girl, isn’t having it; the town’s rumors of a witch are “bull,” she thinks. “Witches ain’t real,” her skeptical thoughts go, as she brings her bike skidding to a halt in front of the witch’s (?) home. But soon enough Snap has joined forces with this supposed witch, a quirky old woman named Jacks who cares for animals but also salvages and sells the bones of roadkill to collectors and museums. Is Jacks a witch? Does she wield real magic? The book remains coy about this until halfway through, but Snap quickly bonds with Jacks, who welcomes Snap into her work, mentors her in animal anatomy and care, and becomes a sort of avuncular (materteral?) queer role model. That bond helps Snap claim her own implied queerness – that, and Snap’s friendship with Lou/Lulu, an implicitly trans schoolmate labeled as a boy but anxious to claim her girlness. All the book’s relationships are worked out with care, including the crucial one between Snap and her overworked but wise single mom, Vi. Leyh’s characterization is slyly intersectional, including sensitivity to class (Lu and Snap are neighbors in a mobile home park, a detail conveyed with knowing matter-of-factness). Almost every character has more to give than at first appears – the sole exception being Vi’s toxic ex-boyfriend, a heavy whose sudden reappearance at the climax is the book’s one surrender to convenience. Everything else feels truly earned. Snapdragon is the kind of book that, described in the abstract, might seem to be playing with loaded dice. In less sure hands, its story could have come across as pat and programmatic, a matter of good intentions as opposed to gutsy storytelling. But, oh, Leyh is absolutely on point here; her mix of irrepressible cartooning and narrative subtlety, of bounce and insinuation, is a wonder to behold. Snap and Jacks are great characters, and in good company. Their world feels real and vital. Leyh infuses their story with grace, understanding, and nonstop energy. I’ve read this book multiple times and expect to read it again. I’d read sequels, if Leyh wanted to offer any. And I’ll follow her whatever she does.

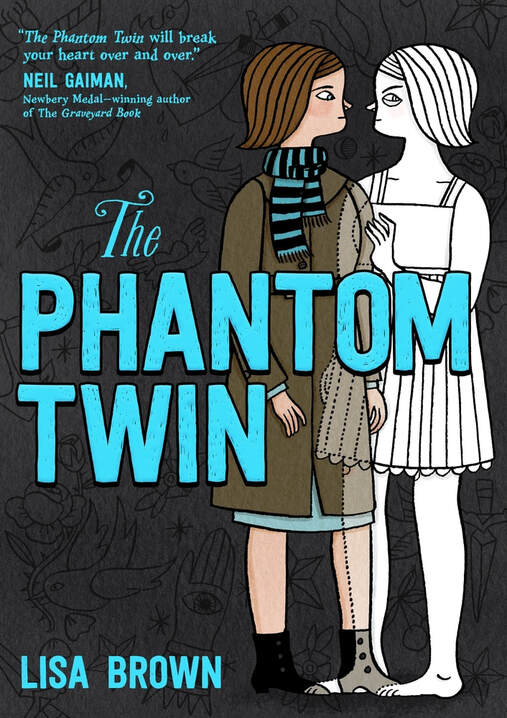

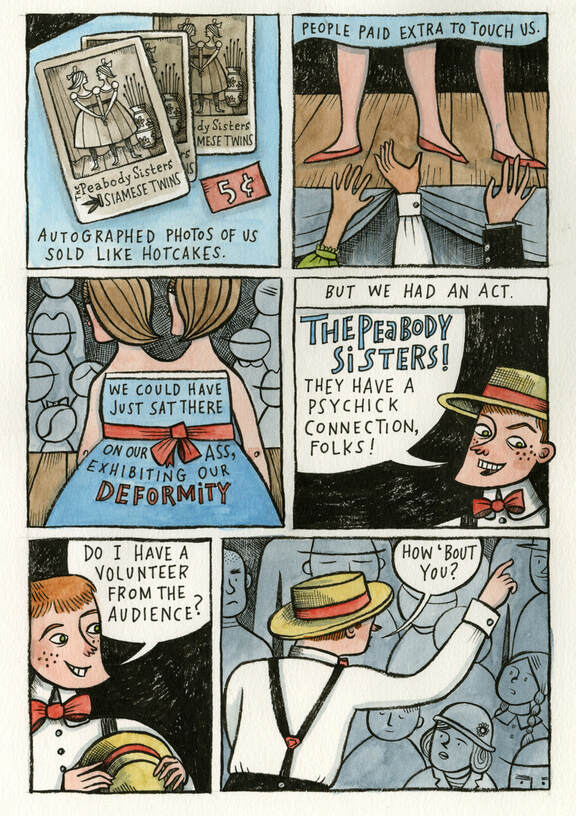

The Phantom Twin. By Lisa Brown. First Second, 2020. ISBN 978-1626729247, US$17.99. 208 pages. The Phantom Twin, a subversive romance set in a carnival freak show, risks creepiness, with a droll style that for me recalls the late Richard Sala (and, indirectly, Edward Gorey). The book treats sideshow freaks in a complex, sympathetic way; Brown captures some of the ironies of freakishness as performance, even as a means of limited agency, and depicts the world of the carnival as an everyday, intimate circle. That circle, though closed to rubes/outsiders, offers a chance at found family and romantic love. Despite what appears to be a straight romance plot, The Phantom Twin strikes me as implicitly queer, and treads on delicate ground, with matter-of-fact depictions of prosthesis, bodily spectacle, and gender ambiguity, as well as characters who, in some cases, embrace enfreakment and reject normate society. Briefly, the plot revolves around a pair of conjoined twins, Isabel and Jane, who perform in a sideshow until a botched separation surgery costs Jane her life, leaving Isabel, for the first time, to fend for herself. Isabel loses an arm and a leg in the process but gains the ghostly presence of her dead, but still very vocal, sister, who manifests as something like a phantom limb. (There’s a semi-Gothic air about all this that would make for a good Laika movie.) The carnival’s tattooed lady takes Isabel in, then introduces her to Tommy, who like Isabel is an artist – in his case, a tattoo artist. An interesting relationship develops, but then Isabel falls into a tryst with a muckraking reporter whose snooping ultimately threatens the whole carnival, which leaves Isabel cast out even by her fellow outcasts. The book’s ending has to resolve, all at once, the problems of thwarted romance and social ostracism – but Brown sticks the landing gracefully, with real boldness, and without too neat a fix. Brown clearly has a passion for the history and culture of the freak show; The Phantom Twin somehow channels Tod Browning’s Freaks while delivering a YA tale with, for me, a warm, affirming payoff. I dug it. My wife Mich, though, who read the book first, found it simply too creepy. We ended up talking about Brown’s harsh depiction of normate society (cruel, vicious, coldly transactional) and the threatening hints of gendered violence scattered throughout (too frank for that notional Laika movie). There were moments, on my first reading, that unnerved me; the world evoked here is quite dark. Yet love redeems it, somewhat – love, and the possibility of community among those deemed freaks. In sum, The Phantom Twin is gutsy and smart. It’s also elegantly drawn and colored, and eminently readable, carried along by restrained yet subtly varied three-tier layouts in classic style. In its embrace of bodily difference (and body art), it’s a courageous, insinuating graphic novel I look forward to re-reading. Many readers, I bet, will find it impossible to forget.

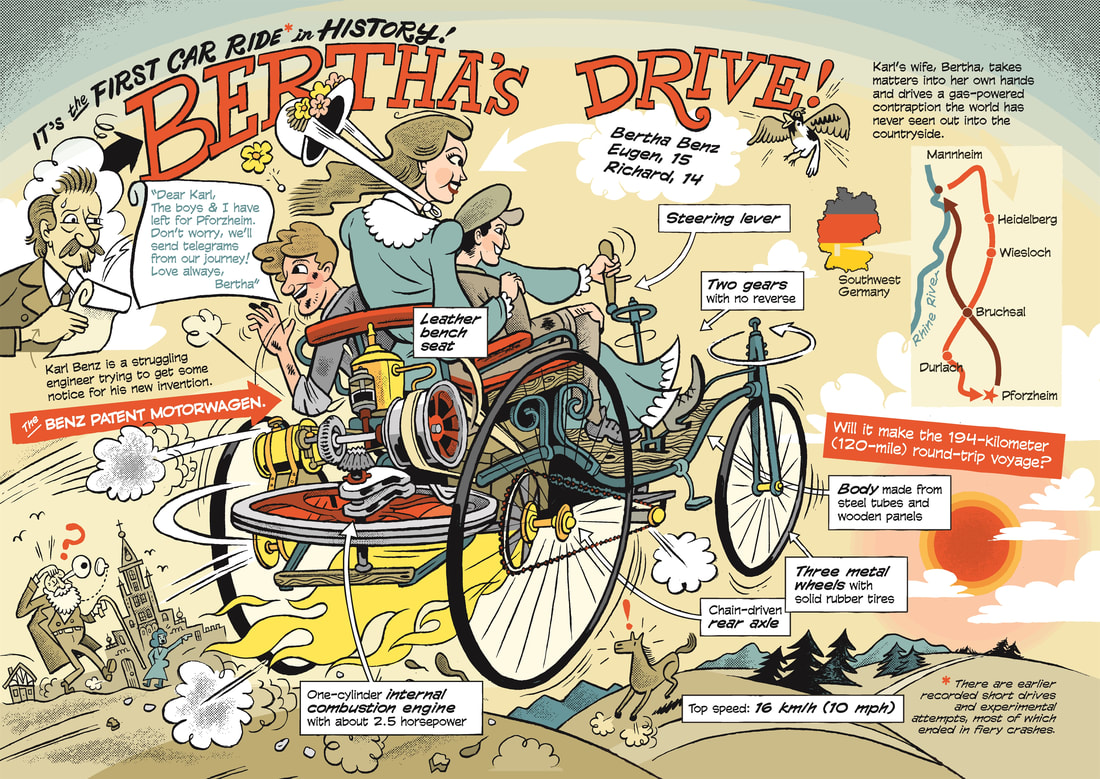

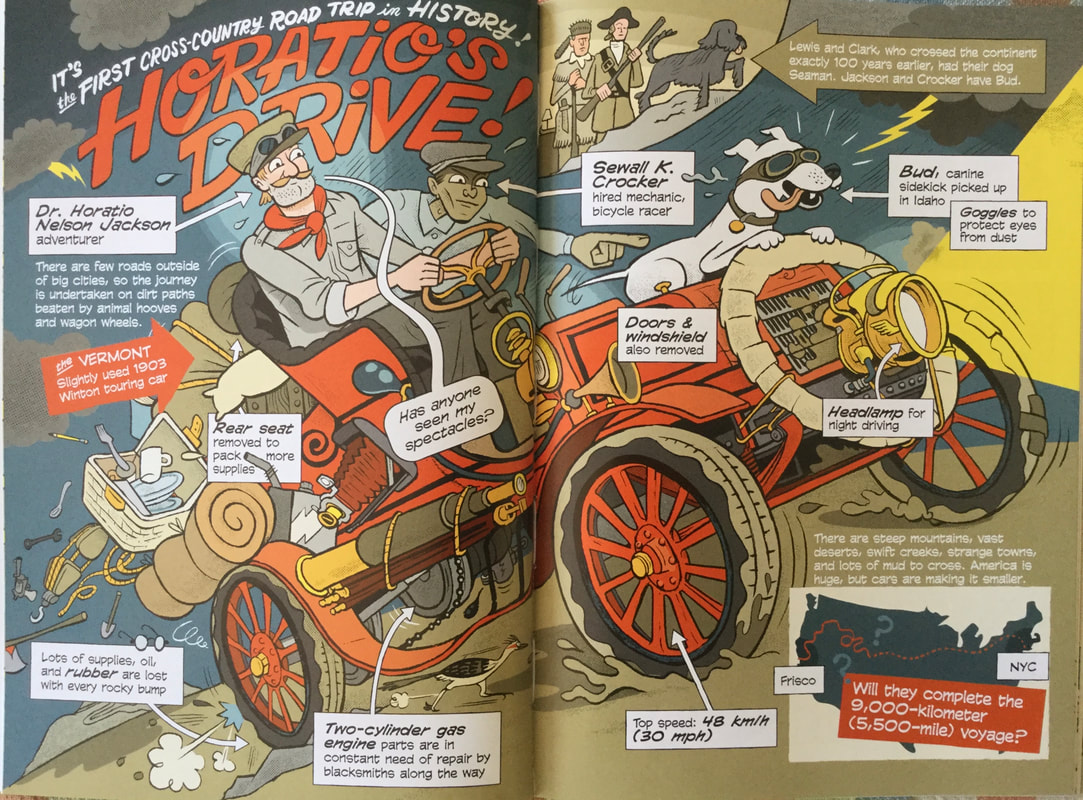

Science Comics: Cars: Engines That Move You. By Dan Zettwoch. Edited by Dave Roman; designed by Zettwoch and Rob Steen. ISBN 978-1626728226 (softcover). 128 pages. $12.99. First Second, May 2019. This one came out in 2019, but I missed it. As much as I dig publisher First Second, I’ve skipped over Science Comics, their didactic middle-grade nonfiction series on topics ranging from dinosaurs to robots, rockets to trees. I should have been paying attention, since the series, launched in 2016, has yielded nineteen books (and counting) and looks like a solid hit. Under editors Casey Gonzalez and (now just?) Dave Roman, Science Comics has welcomed diverse artists and writers, yet the books are strongly branded, sharing a common dress and size (128 pages). Collectively, the series is quite an editorial achievement, as opposed to the creator-driven work First Second usually champions. I suppose that’s one reason I’ve stayed away — but also, I admit, I share the general distrust of children’s informational nonfiction, a critically unloved genre despite outstanding work by creators like David Macaulay (and despite how much time my family and I have spent poring over DK Eyewitness Books). Expository nonfiction for young readers is often slighted as functional, utilitarian stuff, and it’s true that nonfiction books of the Baby Professor type — mechanical and unlovely — are everywhere. I tend to look askance at books that ignore or instrumentalize the pleasures of character and plot. So it took a great cartoonist to get me to try, at last, Science Comics: Dan Zettwoch. I first read Zettwoch in the avant-comix anthology Kramer’s Ergot, then followed him to his first graphic novel, the neglected Birdseye Bristoe (2012), and to Amazing Facts and Beyond (2013), a bundle of mock-didactic, believe-it-or-not strips in collaboration with Kevin Huizenga. Zettwoch’s work is distinctive and, for me, always a draw. He is the master of the cutaway diagram, the cartoon schematic, the absurd yet precise infographic: a successor to both Rube Goldberg and Robert Ripley. Somehow, he manages to be meticulous and loopy at the same time. What’s more, his work often pays tribute to bygone technologies by showing just how they worked. Zettwoch’s cartooning peers into the mechanics of things, rendering them with clarity and joy — so an informational comic about cars would seem like a natural for him. It is. While Science Comics: Cars boasts a few recurring characters who age over the course of the book, it’s not a character-driven narrative; unlike, say, a Magic School Bus adventure, or (I gather) some other Science Comics, it’s not framed as an individual or group journey. The recurrent figures are reminders of the book’s historical through-line, but mainly Cars is a workout for Zettwoch the diagrammer. Though automotive history gives the book an arc and shape, Cars comes closer to encyclopedic Eyewitness style than to a graphic novel. It’s a reminder that comics do not always need traditional strong “storytelling” in order to engage us the way stories do. The book may be organized thematically but coheres graphically. Zettwoch divides the book into four chapters, or “strokes,” named for the modern internal combustion engine’s four-stoke cycle: Intake, Compression, Power, Exhaust. Within these, he repeats certain graphic elements that together lend a sense of order; that is, the book finds its form by braiding and varying key images, layouts, and design conceits. For example, the first two chapters both begin with accounts of historic automobile rides that serve to establish phrases and layouts that recur later. At the same time, Zettwoch throws in, unpredictably, myriad diagrams, charts, and sly jokes, and this graphic playfulness turns Cars into a series of discrete spreads that almost stand by themselves, poster-like. The book demonstrates comics’ diagrammatic nature and the power of design to cluster and clarify big gobs of information — but it also gets a bit drunk on the sheer pleasures of the page. Cars is densely informative, and a feat of design. It excels at the engineering history of autos — but less so, alas, at the social. The book wants stronger thematizing: some social and political threads that would make it, in the end, more than a compendium of wonders. The final chapter, Exhaust, hints at deeper themes, discussing fossil fuels and noxious emissions; belatedly, it suggests the damage automobiles have done to the environment (the globe is shown wreathed by auto exhaust). I figured I was being set up for a reflection on the harm as well as advantages bred by cars — but, no, Zettwoch skitters in other directions, devoting four pages to an insanely detailed chart of trucks, another spread to “Weird Cars,” and then other pages to the histories of car horns, car stereos, etc. A final section covers electric cars and the possibility of driverless cars but gives no sobering sense of the challenges posed by car culture and our reliance on personal vehicles, no sense of ecological or social consequence. Nor does the book deal in detail with automotive safety. It’s as if it can’t face up to harder issues. Instead, it’s a blithe valentine to cars that any gear monkey could love. I get a sense of failed follow-through and of implications left unexplored — that is, I found the book’s finale disappointing. To his credit, Zettwoch’s version of car history is fairly inclusive, honoring women as engineers and innovators and spotlighting non-white figures as well. The book offers a bright, affirming view of a shared car culture. Yet Cars does not come to terms with what the overabundance of autos might mean for our common future. Zettwoch’s love of automotive engineering comes through, but the “science” part of the project feels incomplete without reckoning on the environmental impact of automobiles. Road not taken? Opportunity lost, I'd say. That said, Cars remains a dazzling exercise in show-and-tell, a master class in comics as diagramming and design. Though it may not quite add up, it overflows with ingenuity and pleasure. As it turns out, Science Comics can be interesting comics indeed. I’ll read more, with hope.

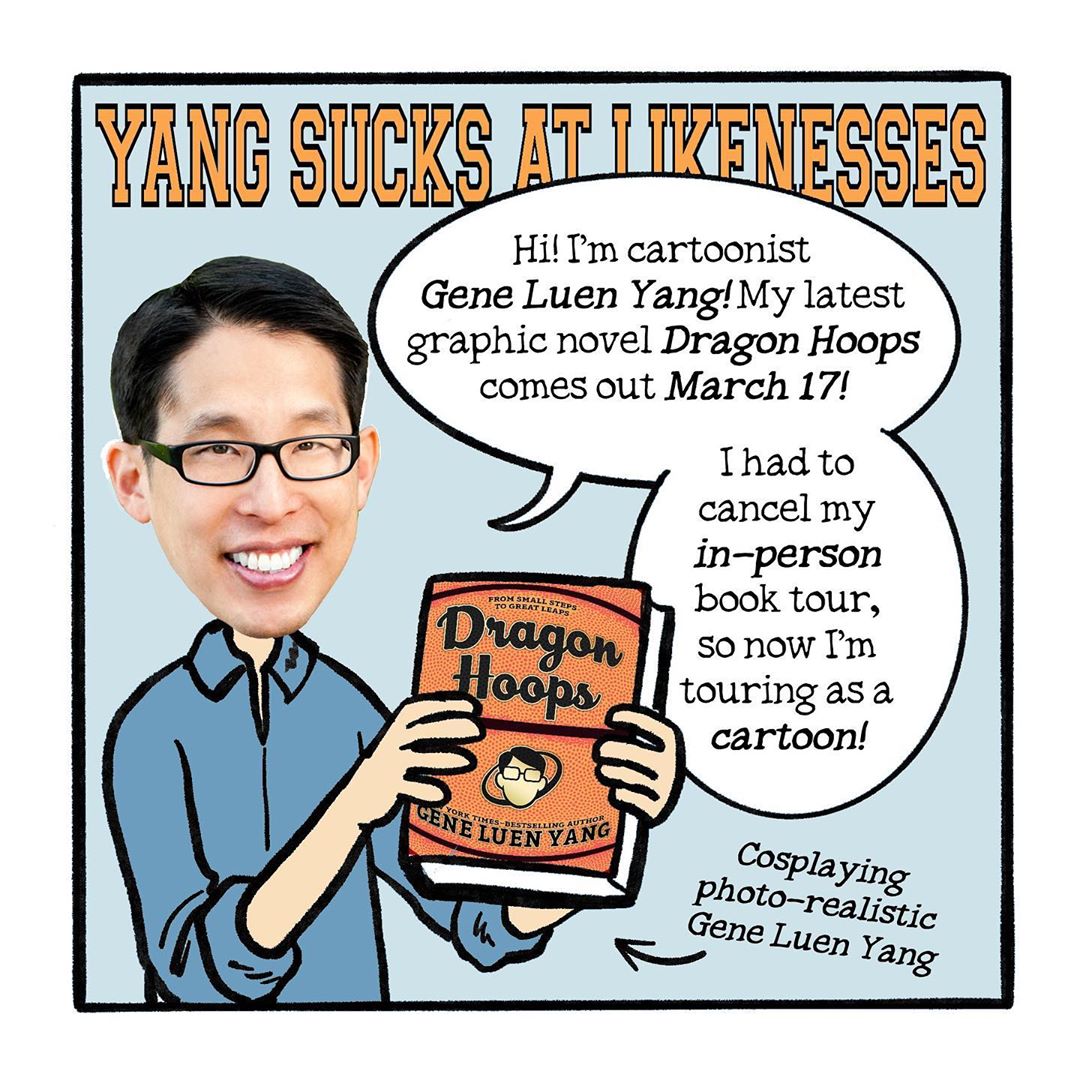

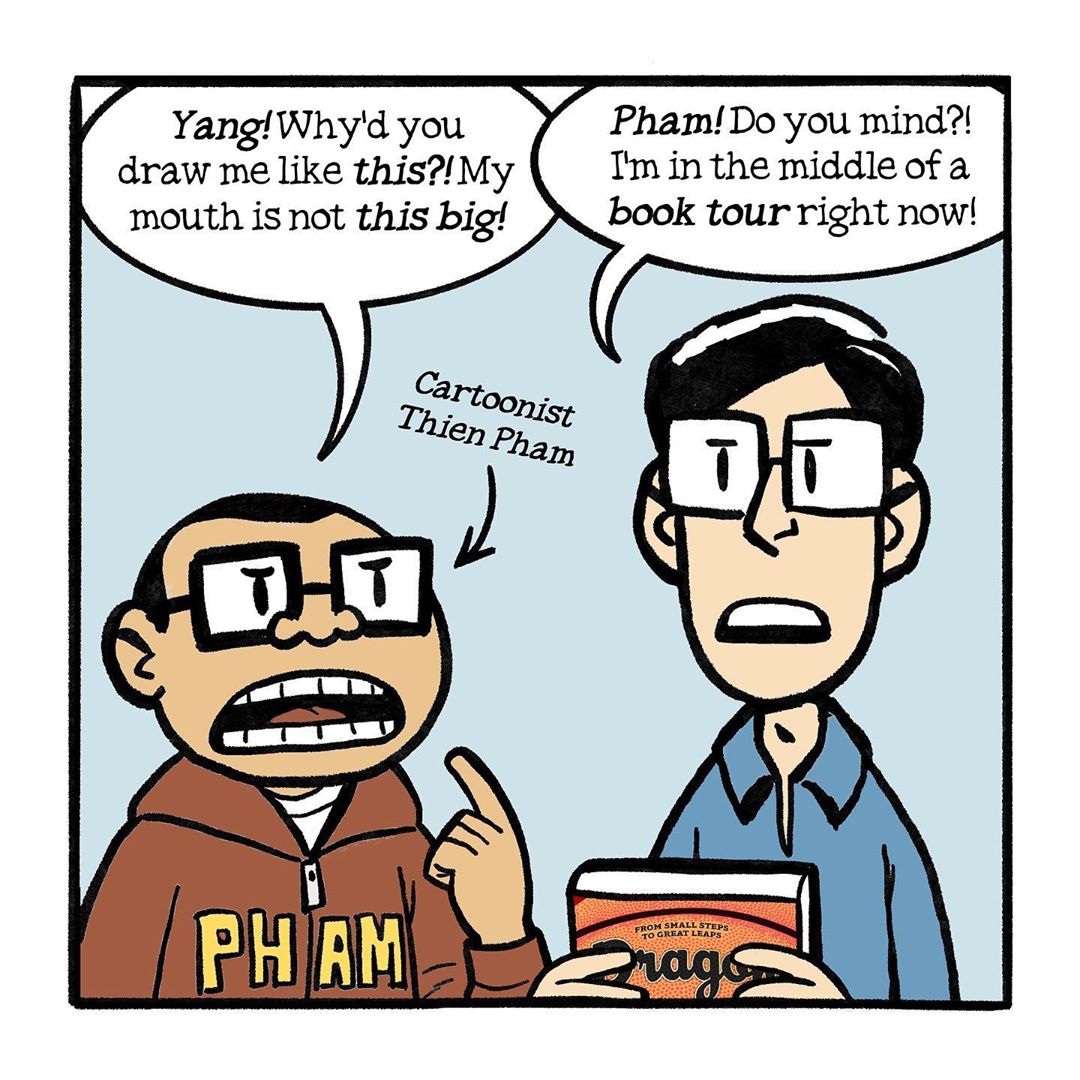

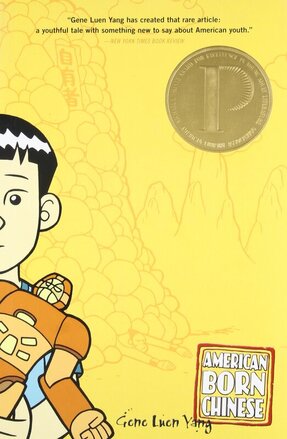

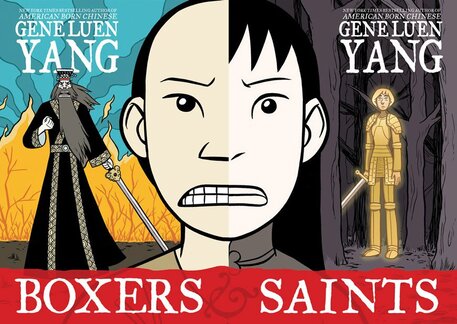

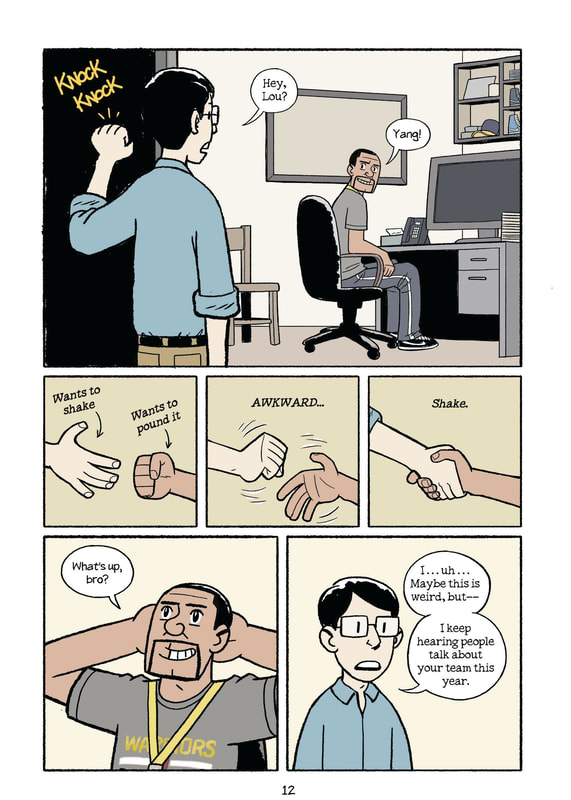

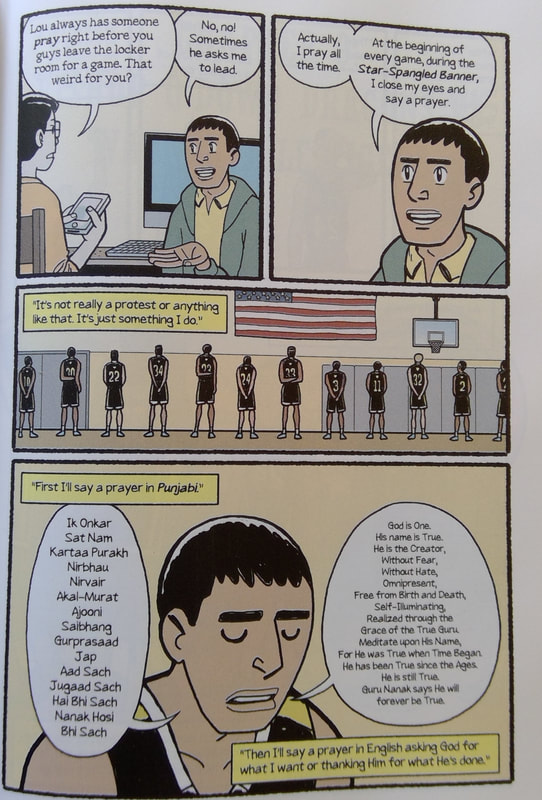

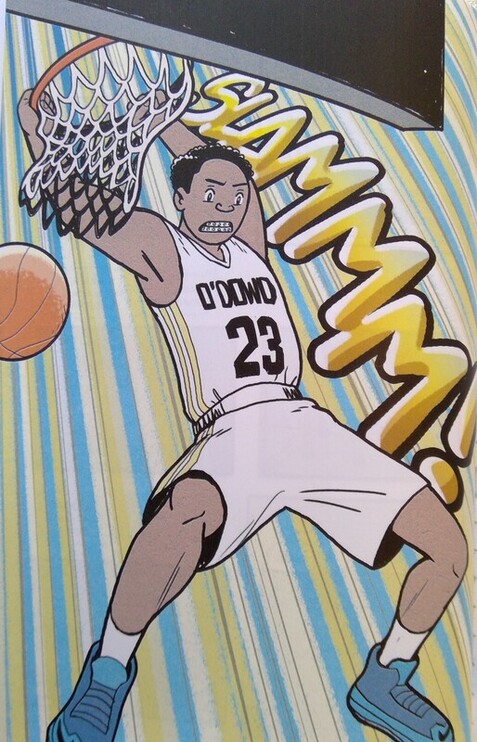

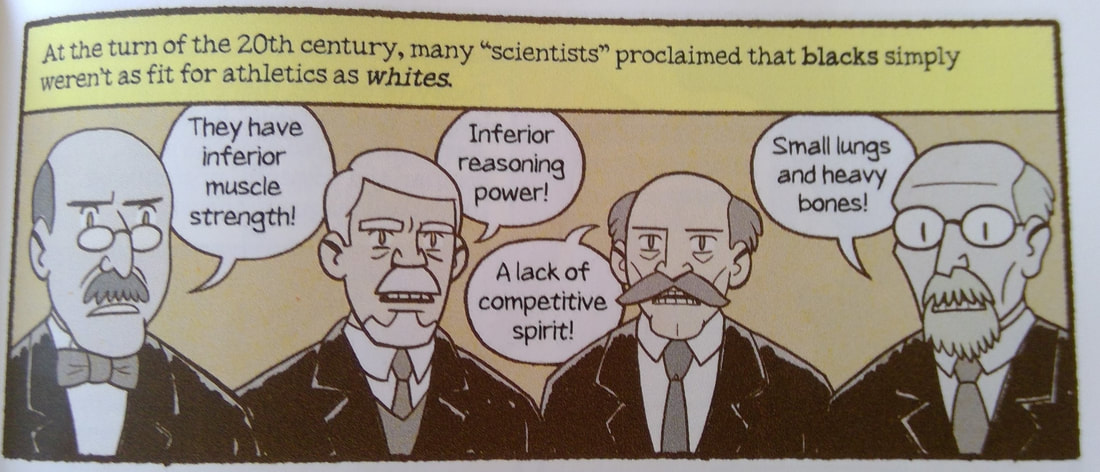

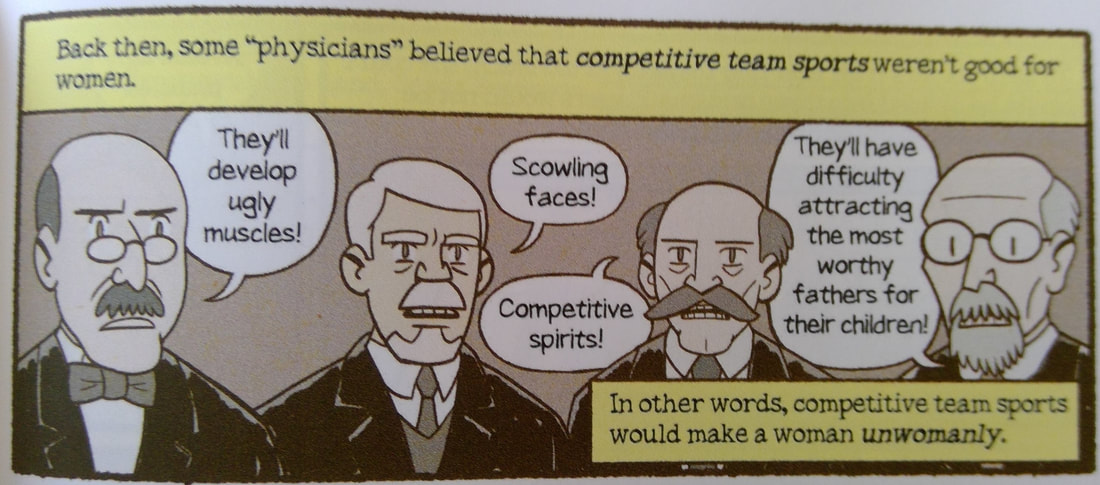

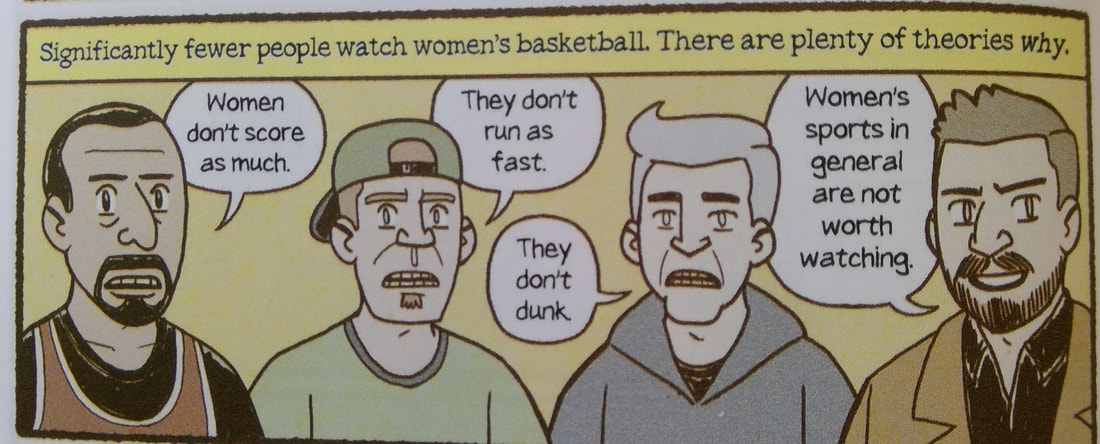

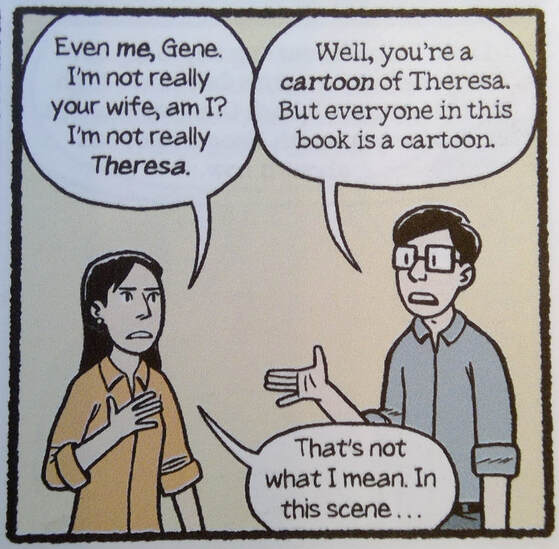

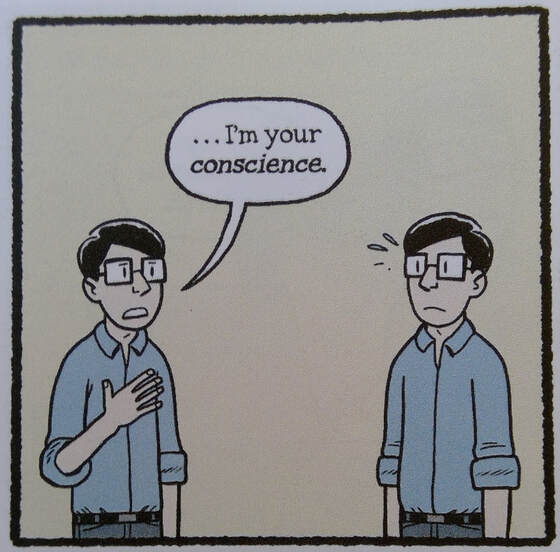

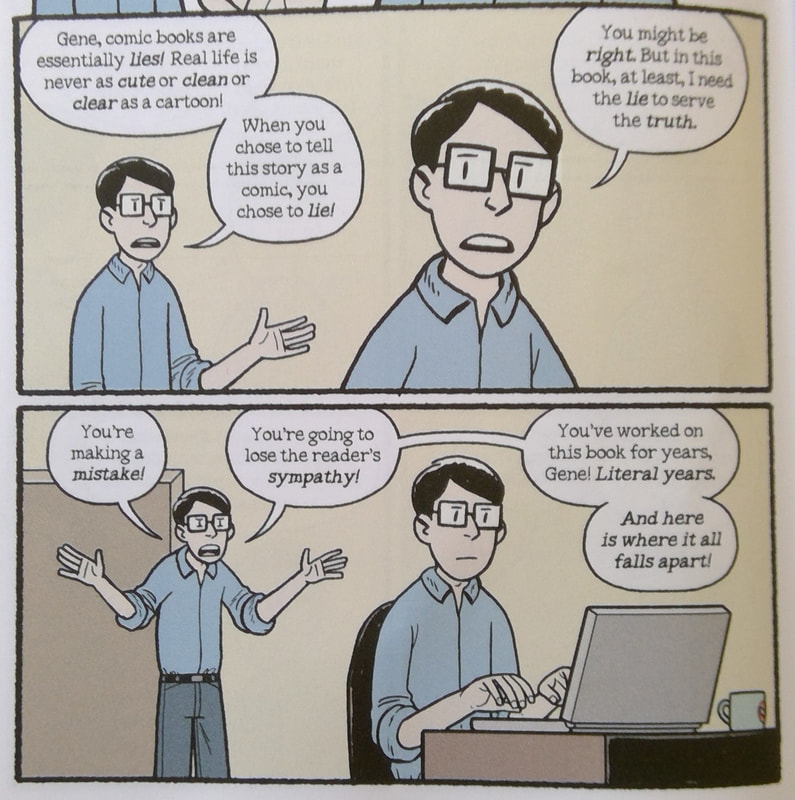

Dragon Hoops. By Gene Luen Yang. Color by Lark Pien. First Second. ISBN 978-1626720794 (hardcover), $24.99. 448 pages. March 2020. Recently Gene Yang has been out touring in support of his newest graphic novel, the just-released Dragon Hoops. But of course he hasn't been touring in the flesh; the COVID-19 pandemic has had him—like so many of us—holed up at home, trying to find creative new ways to engage with both his family and his public. Happily, he hit upon the idea of a virtual book tour: that is, promoting Dragon Hoops through a series of Instagram comic strips in which he responds to readers’ questions. These quick comics are formulaic, but the formulas are clever and engaging: Yang repeats shots and gags across the series, making it feel much like whistle stops before a loving audience that tends to ask the same few questions again and again. Of course, these comics are self-deprecating—more than anyone else, Yang is the object of his own jokes. He makes an excellent comic strip character. Humorous self-deprecation is one of Yang’s constants. He used to self-publish under the imprint Humble Comics, and if you’ve seen him speak you know that he excels at genial self-mockery. Yang plays humble the way Liszt played the piano—it’s his instrument. But don’t let him fool you: he is a gutsy and ambitious narrative artist whose work walks a tightrope between charming accessibility and willed difficulty. Yang takes chances. In particular, his solo graphic novels (as opposed to his many collaborative works) are fearsome high-wire performances. Dragon Hoops is no exception. Yang’s comics tend to be structurally tricky, thematically bold, and psychologically sharp. His breakout book, American Born Chinese (2006), semi-autobiographical yet fantastical at once, interweaves three stories in three different genres, until a startling moment that turns those three tales into one. The novel oscillates between ingratiating humor and terrible pain (in fact, those two tones are co-present throughout). Mixing myth fantasy, earthbound middle-grade school story, and arch sitcom, American Born Chinese is great comics, capitalizing on the form’s stable-unstable, multimodal heterogeneity to tell an immigrants’ son’s story, one of divided identity or fractured self. At bottom, it’s a story about internalized racism and self-hatred. A nervy book, it freely adapts China’s legendary Journey to the West, while at the same time insinuating a Christian allegory and riffing on Transformer/mecha pop culture. Moreover, it dares a form of grotesque satire, in which hateful, grossly racist anti-Chinese stereotypes reflect the protagonist’s self-loathing (a strategy as impious and risky as Art Spiegelman's notorious animal metaphor in Maus). In sum, American Born Chinese revealed Yang’s propensity for large-scale structural conceits that enact his own ambivalence and complex sense of identity. It was, is, daring. Yang’s follow-up project, Boxers & Saints, goes one better. A two-volume novel about China’s Boxer Rebellion, it’s a magic-realist historical fantasy in which the twin volumes represent, in a kind of tense counterpoint, both Chinese nationalist (Boxers) and Europeanized missionary (Saints) perspectives. Pitting the story of a young man who is an anti-colonial revolutionary against that of a young woman who is a Christian convert, Boxers & Saints balances Yang’s Catholicism against his pained awareness of Western imperialism and racism, while also critiquing strands of misogyny in traditional Chinese culture. The resulting two-headed novel, rather shockingly violent for Yang, represents a dramatic argument: a psychomachia in which different facets of Yang contend with each other, bitterly. Boxers completes Saints, and vice versa, and both volumes sting. This project shows, again, Yang’s penchant for teasing out self-conflict by counterposing different plots (in this case, different books!) and engineering complex structures. Identity in his books is as tricky as the plots: dynamic and never settled, an anxious balancing act. Yang's ingenious plotting, and an overall sense of high personal stakes, of storytelling wrung from pain, transform what could be flatly didactic into harrowing stuff. Dragon Hoops aims for this quality too, though it lacks the big structural conceits of the three-part American Born Chinese or two-part Boxers & Saints. It differs in another important way too: this time the tale is not historic, mythic, or crypto-autobiographical, but instead a literal memoir, an account of a year in Yang’s life as a teacher at Bishop O’Dowd High, a Catholic school in the Bay Area. Dragon Hoops is the longest overtly autobiographical work Yang has done. Yet it’s really about (huh?) basketball: on one level, Bishop O’Dowd’s varsity men’s basketball team, the Dragons, hungry for a state championship, but more broadly the entire history of the sport and how it intersects with race, class, and even Catholic schooling. In short, Dragon Hoops takes on basketball as a social force. This is something that the book’s version of Gene, archetypally geeky and sports-averse, has to struggle to understand. The story follows Gene from standoffish sideline observer (he is, at first, simply a storyteller looking for a new story) to ardent booster of the school’s basketball squad. At the same time, it charts a major shakeup in Yang’s own life, and offers multiple stories of struggle and vindication if not redemption. Further, it explores ethical issues involved in coaching, mentoring young people, and even Yang’s own storytelling. In fact, Yang worries on the page about what he is doing on the page. Here the book seems boldest--or perhaps most vulnerable? Dragon Hoops is long and complex (at about a hundred pages longer than Boxers, it is Yang’s heftiest single volume). Somewhere between intimate memoir, journalism, and oral history, it profiles the players on Bishop O’Dowd’s team, observes the complex social dynamics of their lives, and sets us up for, yes, a nail-biting climax on the court, at the longed-for championship game. Simultaneously, though, it recounts the creation and democratization, or broadening, of basketball, in a series of historical vignettes—while also depicting a transformative moment in Gene’s uncertain career in comics. That career comes to a sort of fortunate crisis when Gene, startled and uncertain, is offered a chance to write, of all things, Superman. Yang thus parallels the team’s story with a node of decision in his own life. In this way, the book explains why he is no longer at Bishop O’Dowd, and becomes a bittersweet valedictory to his seventeen-year stretch there (and perhaps a way of prolonging his connection to the school?). There’s a great deal happening in Dragon Hoops, then—the book’s seemingly straightforward structure conceals yet another gutsy high-wire act. This book is jammed full. Starting from a prologue in which Gene, reticent and awkward, seeks out Dragons coach Lou Richie, the story shuttles between present-day profiles and historical background, while also packing in loads of on-court basketball action. The team’s season, and Gene’s growing relationship with “Coach Lou,” are the spine of the book, but Yang freely intermixes other elements, with special attention to particular Dragons and how their team collectively embodies diversity. Chapters depicting important games alternate with chapters devoted to key players (in this sense, the book’s structure is very deliberate). Yang uses the players’ backstories both to celebrate basketball as an inclusive and egalitarian sport but also to point out various problems, notably racism and sexism, in the history and culture of the game. One chapter is devoted to a pair of siblings, Oderah, star of O’Dowd’s championship women’s basketball team, and her younger brother, Arinze, now part of the men’s varsity squad; the two are constant rivals, yet fiercely loyal to each other. Another chapter profiles Qianjun (“Alex”) Zhao, a Chinese exchange student on the Dragons’ team. Another focuses on Jeevin Sandhu, a Punjabi student of the Sikh faith—and here Yang focuses on the challenges of assimilation, while also providing, in effect, a brief introduction to Sikhism. There’s more. Dragon Hoops depicts James Naismith, who invented basketball in 1891; Marques Haynes and his fellow Harlem Globetrotters, who helped integrate the game; Senda Berenson, who launched women’s basketball; Yao Ming, the first star of Chinese basketball to thrive in the NBA; and other notables in the game’s history. Yang smartly interweaves present and past: the chapter on Jeevin also recounts the rise of Catholic schooling and the career of early NBA star George Mikan, a Croatian American player from a Catholic seminary; Yang then acknowledges that Jeevin, as a Sikh, is an outlier in Bishop O’Dowd’s Catholic culture (a scene of Jeevin reciting the Mul Mantar, a Sikh prayer, complements other scenes of praying in the book). Similarly, the chapter on Oderah and Arinzes weaves in Berenson’s story and the rise of the women’s game, including a historic dunk by pioneering college player Georgeann Wells. You can feel Yang matching up elements from past and present to build a tight, cohesive book. Visually, Dragon Hoops is likewise purposeful and designing. Breathless scenes of action on the court, sometimes parsed down to the split second, recall the sort of intense basketball manga popularized by Takehiko Inoue (Slam Dunk, Buzzer Beater, Real). These scenes attain an energy and forcefulness that exceed Yang’s previous work (even the martial violence of Boxers & Saints). There are sequences that fairly set my pulse racing. What makes these explosions of action thrilling is the way the book as a whole carefully measures out its storytelling, and uses the very controlled braiding of repeated imagery to reinforce its themes. Yang recycles and repurposes the same signal images over and over, to point up thematic parallels between past and present, among the different players, and between the Dragons’ quest for the championship and his own concern about going “all in on comics” as a career. Dragon Hoops is a library of key images, reworked and re-inflected (indeed, it could take the place of the vaunted Watchmen when it comes to classroom lessons about braiding!). In fact, it’s a brilliant sustained feat of cartooning for the graphic novel form; the book echoes back and forth, as Yang plays the long game. There’s a kind of nervousness, though, behind Yang’s cleverness. Dragon Hoops is an anxious, self-conscious work. Like Spiegelman’s Maus—and a great many other graphic memoirs since—it reveals and worries over its own stratagems. The authorial notes in the book’s back matter frankly discuss Yang’s sourcing and his occasional resort to artistic license. Said notes relate to the main story dialectically and at times critically (reminding me of the disarming notes in several books by Chester Brown). In particular, Yang admits that he has cast his wife Theresa as, essentially, his sounding board and proverbial better half: wise and practical, humorously tolerant of his anxieties, and full of advice and encouragement (or reasonable doubts about his judgment, as the occasion demands). Talking to Theresa becomes a means of registering Gene’s doubts about his own project, and the sometimes choppy ethical waters that the project gets him into. Though Theresa makes an impression, she does not really emerge as a full-blown character (and the same could be said of Theresa and Gene’s children). Yang notes that he took “particular liberty” with her dialogue: “I figured I could because, y’know, we’re married.” His notes are full of revealing asides like these, which invite a closer look at Dragon Hoops as a performance and a made thing, not just an artless recording of real-life events. Yang’s self-reflexive disclosure of his artistic feints happens not only in the back matter but also in the main story. Dig these two successive panels, on either side of a page turn: In particular, Yang depicts himself worrying over a single compromising plot point: a deeply troubling element of real life that threatens his desired “feel-good” story but that he feels he cannot omit. That ethical sore point is seeded about a third of the way into the book, after which Gene frets and frets over it—until a moment about four-fifths in, when Gene, or rather the book, enacts its moment of decision: Readers of Maus may be reminded of Art’s insistence that “reality is too complex for comics"—which Yang echoes here, stating that comics are “essentially lies.” (Spiegelman too sometimes casts his wife, Françoise Mouly, as a sounding board whose dialogue makes his work’s ethical complications clearer.) In the case of Dragon Hoops, this sort of self-reflexive gambit becomes a fundamental plot element, in fact a suspense generator, long before Yang reveals precisely why. We spend a good part of the book wondering what he is hiding, and how he will reveal it (of course, this plot tease makes it obvious that at some point he will). This isn’t a terribly original move—graphic memoirs have been depicting the rigors of their own making since at least Justin Green—but here it feels almost like a forced move, as if Yang was compelled to it by unnerving real-world details that he could not wish away. Anxiety over this point fundamentally shapes the book’s narrative structure. Dragon Hoops, then, perhaps seeks to inoculate itself against criticism. That is, Yang’s self-critical gambits (there are many) may be meant to deflect charges that his expert storytelling massages the truth a bit too much. I’m not sure that such charges would be fair—but I confess I don’t think Dragon Hoops is Yang’s most convincing graphic novel. Whereas American Born Chinese and Boxers & Saints continue to hint at mixed feelings even as they aim for conclusiveness and wholeness, this book wants to feel emphatically resolved. Yang’s trademark ambivalence yields to a sort of boosterism. At times, Dragon Hoops seems to apply the “underdog” template of most sports stories rather uncritically; for example, the book registers some complicated thoughts about sports, coaching, and Catholic education that its final pages don’t so much resolve as hush. Me, I would have liked to see more critical engagement of what it means to turn young athletes into media stars. I would have liked to see more of Coach Lou’s self-questioning. Dragon Hoops is smart and honest enough to acknowledge problems in the culture of sports, but still wants us to cheer at the final buzzer. Maybe it’s an ironic tribute to Yang’s storytelling that, in the end, I wasn’t quite there. In any case, the book’s reigning structural parallel—how the courage and tenacity of the Dragons empowers Yang to go “all in” himself, as an artist—feels a bit rigged alongside the terrible dilemmas depicted in his previous novels. But, man, it's hard to begrudge Yang the effort, because so much good stuff happens along the way. Dragon Hoops captures a culture, community, and season vividly, and is the very definition of what we should want from a major artist: a step in a new direction, and a dare-to-self that plays out in complex ways. No one could accuse Yang of making things easy on himself. And the book has taught me a lot. As my wife Mich and I take our daily break from isolation, walking the quiet neighborhoods around us, waving (distantly) at passers-by, we see a lot of basketball hoops on driveways and in yards. In fact, a couple of days ago, as we walked uphill through another neighborhood, we heard the sounds of shooting hoops before we came upon the sight: a quick dribble, a silence, a thudding backboard, then more of the same. Sure enough: someone was practicing basketball, solo, in a rear driveway, just barely visible above a tall gate. I had this book on my mind, and had to smile.

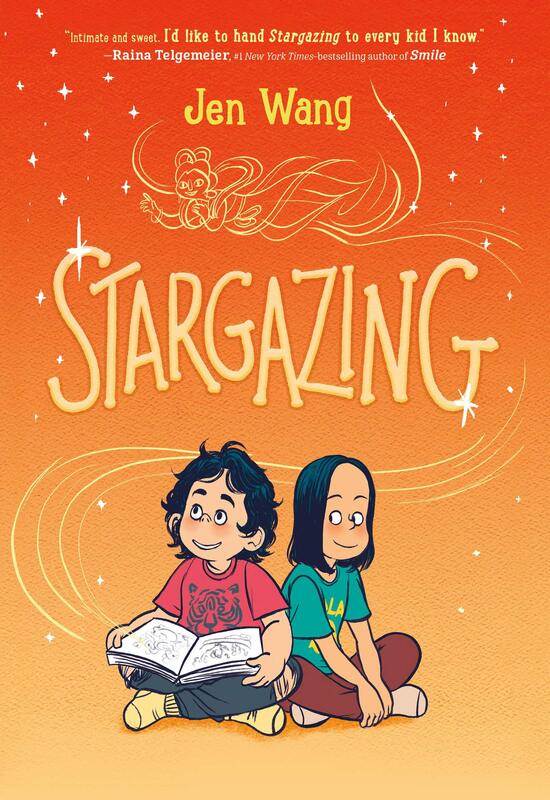

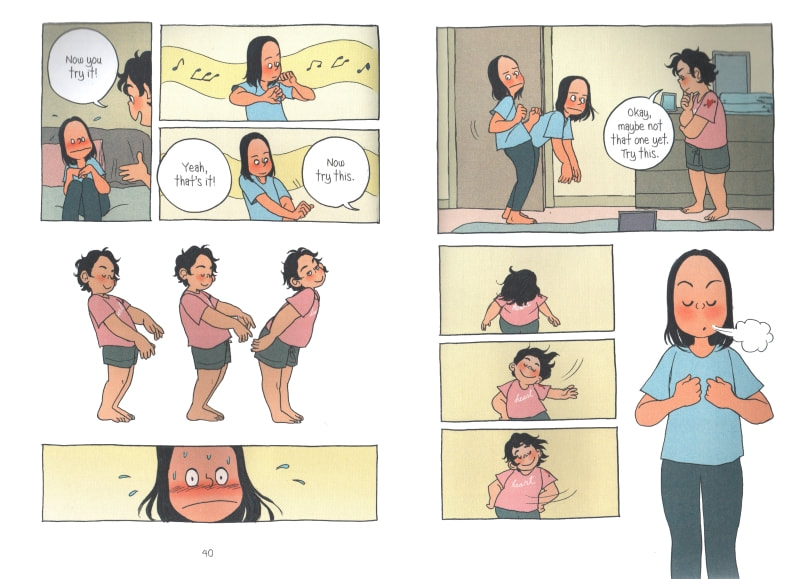

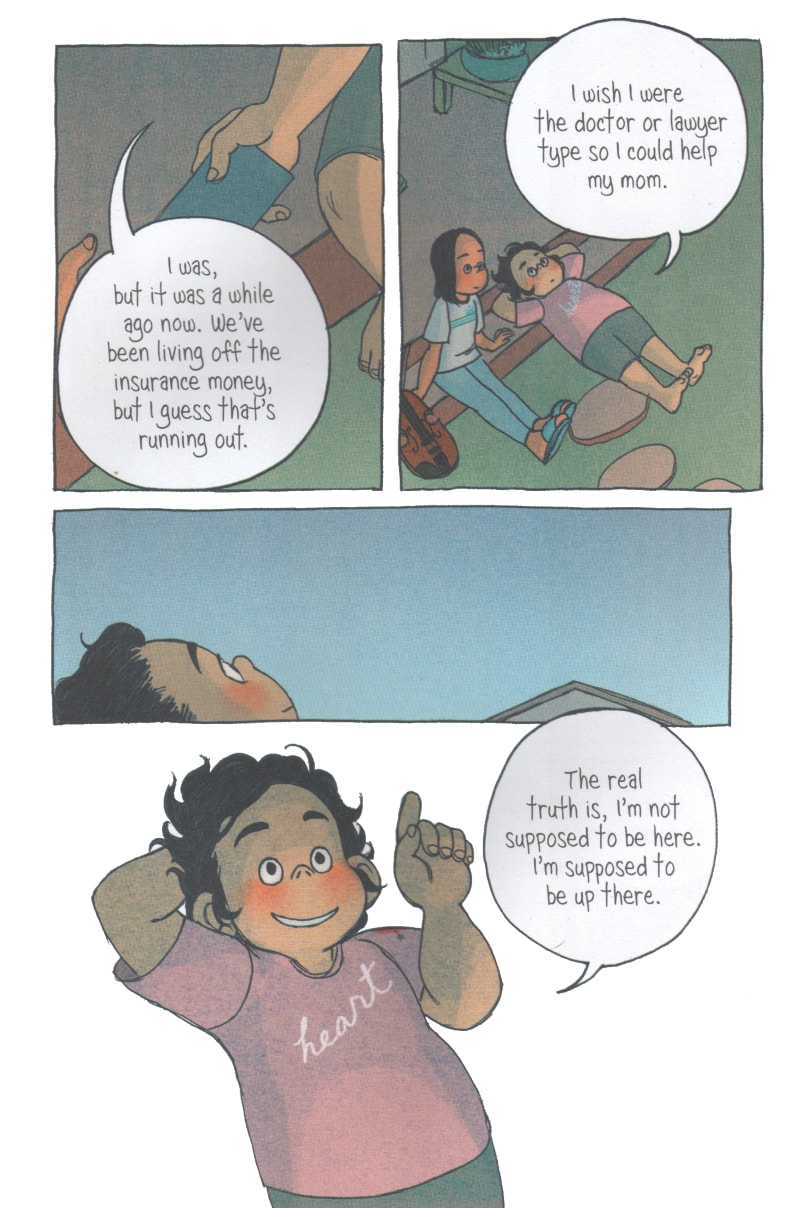

Stargazing. By Jen Wang. Color by Lark Pien. Song lyrics by Hellen Jo. First Second. ISBN 978-1250183880 (softcover), $12.99; ISBN 978-1250183873 (hardcover), $21.99. 224 pages. Stargazing, Jen Wang’s follow-up to last year’s The Prince and the Dressmaker, is recognizably by the same artist—one of America’s best comics artists. Yet it’s a very different sort of book. A middle-grade graphic novel about friendship and jealousy among girls, it falls squarely into Raina Telgemeier territory: a school story about finding your complementary opposite and becoming friends, but then pulling back, but then stepping forward again. As it traces a relationship between two girls, Christine and Moon, Stargazing evokes the camaraderie and intimacy of friends sharing secrets. At the same time, it registers how selfishness and anxiety may complicate our friendships. Wang treats small betrayals among school friends as the stuff of moral drama. In particular, she pays attention to what it may mean to be an immigrant’s daughter driven by certain dreams of success, and how such a driven child might look to another girl, one far from her in class and temperament, for a kind of relief, a liberating counter-example of a life lived more freely or less anxiously. But of course that “other” girl has complications of her own. Along the way, Wang conveys differences of class and circumstance within a Chinese American community, showing how adaptation and resistance may take diverse forms. Building on her own memories of girlhood, and detailing how different families may cleave to different standards and impose different pressures, Wang fashions a portrait of community and an understated story of girlhood friendship with a very particular cultural setting. In short, this is a terrific book. Female friendship is a, or maybe the, abiding theme in post-Raina graphic Bildungsromane. I’ve noticed various author-artists tacking in that direction (KinderComics readers may recall, for example, reviews of Larson’s All Summer Long or Brosgol’s Be Prepared). At the recent PAMLA conference in San Diego, scholar Erika Travis (California Baptist University) presented on this very topic, drawing on Jamieson’s Roller Girl, Bell’s El Deafo, and Hale and Pham’s Real Friends for examples. She showed how these books stake out the traditional concerns of girls’ middle-grade books, only in comics form. Stargazing leans in that direction too—it’s the simplest, most grounded of Wang’s books, harking back to the slice-of-life of Koko Be Good but framed as a school story. Thematically, it invites comparison to Telegemeier’s recent Guts; for example, in both books characters use their art to cement relationships. Stargazing, though, shoulders the added complexity of immigrants’ children in a specific Chinese American context. Its protagonist is weighed down by her father’s aspirations for success—perhaps an oblique commentary on the model minority myth—and this complicates, almost undermines, her friendship with her complementary opposite. Christine, studious, high-achieving, and serious, contrasts sharply with her new neighbor Moon, impetuous, high-spirited, and hyper. The former is quiet and restrained, and driven to academic success—partly by her well-meaning but at times insensitive father. The latter is a spitfire: bright and scattered, cheerfully defiant of rules, and prone to cold-cock other kids who are mean to her friends. Christine is the idealized academic success, Moon the subject of nervous gossip. Christine’s family is well-off; Moon’s single mother struggles to make ends meet. When Moon and her mother move into the guest home rented out by Christine’s family, the two girls strike up an unlikely friendship, and Moon’s energy rubs off on Christine, whose reserve begins to melt a bit. Moon introduces Christine to K-pop and dance. Christine’s family introduces Moon to Chinese language class (but it doesn’t take). The two bond, in a series of delightful scenes. Moon confesses to Christine her belief that she, Moon, is not an ordinary Earth girl but rather a creature from the stars—that one day she will return to a home on high. Sharing this with Christine is a gesture of friendship. Christine, though, prompted by anxieties about academic success and social approval, backs away from that friendship. A small betrayal bumps up against a major crisis, as Moon has to face a serious, life-altering event—and Christine, dogged by guilt, has to own her past behavior and, somehow, move forward. She struggles. She hides. But hiding can't last forever. This outwardly simple plot is treated with the utmost delicacy, and a great many insinuating cultural details that enrich the context. More to the point, its resolution is moving: every time I reopen the book I get choked up. Wang is that good. While Stargazing may be in, broadly speaking, familiar territory, it isn’t generic at all. It seems to be a dialogue around Chinese American experience and different ways of being a Chinese American girl. It evokes specific familial and communal settings with a brilliant economy. At the same time, it’s aesthetically gorgeous: Wang’s cartooning and layouts boast an elegance and lightness of touch that are rare. The book’s use of negative space—of unenclosed figures and the whiteness of the page—gives it a free-breathing, eminently readable quality. The same delicacy with character and emotion seen in The Prince and the Dressmaker comes through here, abundantly; Wang knows how to capture the finest nuances of expression. This is simply first-rate comics—and highly recommended.

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed