|

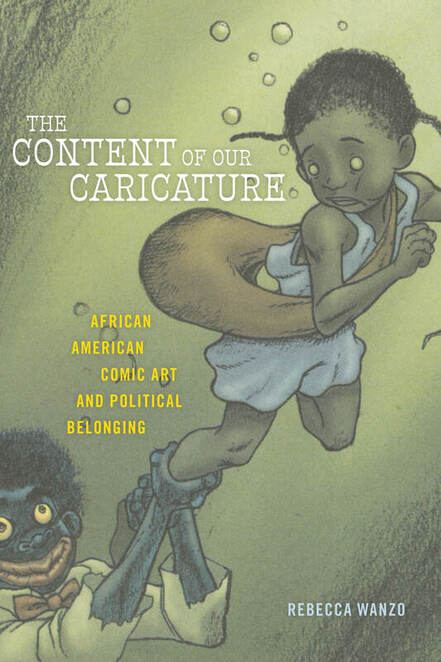

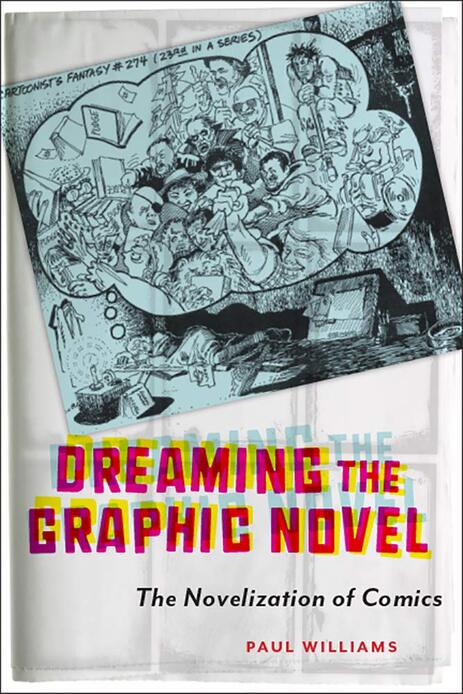

Despite the ravages of COVID, I feel optimistic about my field, comics studies, and glad to be part of it. Important, eye-opening research continues apace, and my understanding of the field keeps getting bigger (which is to say that I keep getting challenged, in invigorating ways). The scholarly institutions I’ve been part of are doing what they can to bring communities together in spite of the pandemic. Academic conferences, independent comics festivals, and large-scale comic-cons have offered virtual programming this past year, so that life and study at home don’t seem quite so lonesome. I’m particularly happy to see the International Comic Art Forum’s slate of monthly virtual events, still ongoing, and the call for next summer’s Comics Studies Society conference. On a personal note, this year saw, at last, the publication of a long-term project of mine, Comics Studies: A Guidebook, a classroom-ready anthology co-edited with Bart Beaty (and published by Rutgers University Press). Bringing this book into the world took many years, but I'm proud of the results: essays by twenty scholars on the history, form, genres, production, and reception of Anglophone comics. These essays succinctly explain fundamental issues in the comics studies field, crystallizing complex questions, if I may say so, in ways that no book has done before, and often with real conceptual originality. I thank our contributors for their steadfastness, patience, and brilliant writing; the life of the Guidebook is in their essays. If you're a student or teacher of comics, I hope you'll check our Guidebook out. Again speaking personally, I had the pleasure to contribute to another comics studies volume this year, Kim Munson's Comic Art in Museums (published by the University Press of Mississippi), a groundbreaking collection focusing on the exhibition of comics in museums and galleries. If you want to know more about how comics came to be exhibited and recognized in the art world, then this book can give you a grounding. The history that Munson and her contributors lay out is longer and more complex than you might expect. (I am honored to have two pieces in the book, and to have curated the 2015 Jack Kirby exhibition that is the focus of several pieces.) What follows is a handful of comics studies books that I'm currently reading, books that I find particularly exciting at this moment. This is not meant to be a best-of for 2020, since, goodness knows, I've had trouble keeping up academically during the long lockdown (and there are new books that I haven't had a chance to dive into yet, such as Anna Peppard and company's Supersex: Sexuality, Fantasy, and the Superhero, or Frederick Luis Aldama et al.'s massive Oxford Handbook of Comic Book Studies). These are just a few of the books that recently struck me as expanding the boundaries of the field: Sean Kleefeld, Webcomics (Bloomsbury). Eszter Szép, Comics and the Body: Drawing, Reading, and Vulnerability (The Ohio State University Press). Disclosure: I co-edit, along with Jared Gardner, Rebecca Wanzo, and acquiring editor Ana Jimenez-Moreno, the OSUP's Studies in Comics and Cartoons series, which published Szép's book.) Gwen Athene Tarbox, Children's and Young Adult Comics (Bloomsbury). Rebecca Wanzo, The Content of Our Caricature: African American Comic Art and Political Belonging (NYU Press). Paul Williams, Dreaming the Graphic Novel: The Novelization of Comics (Rutgers UP).

0 Comments

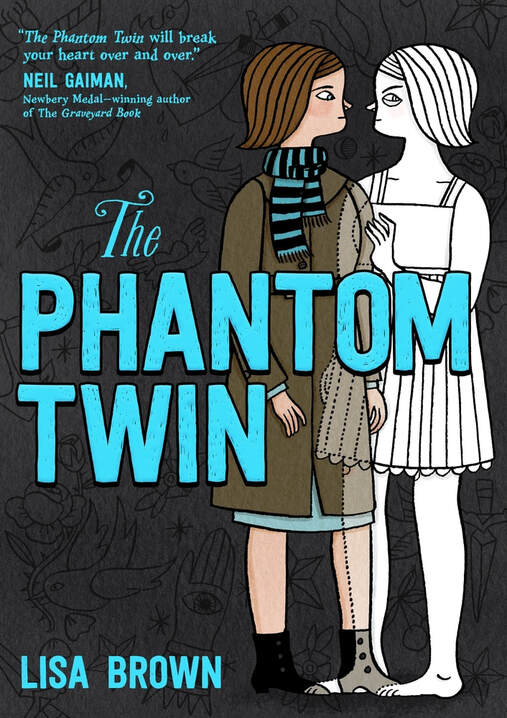

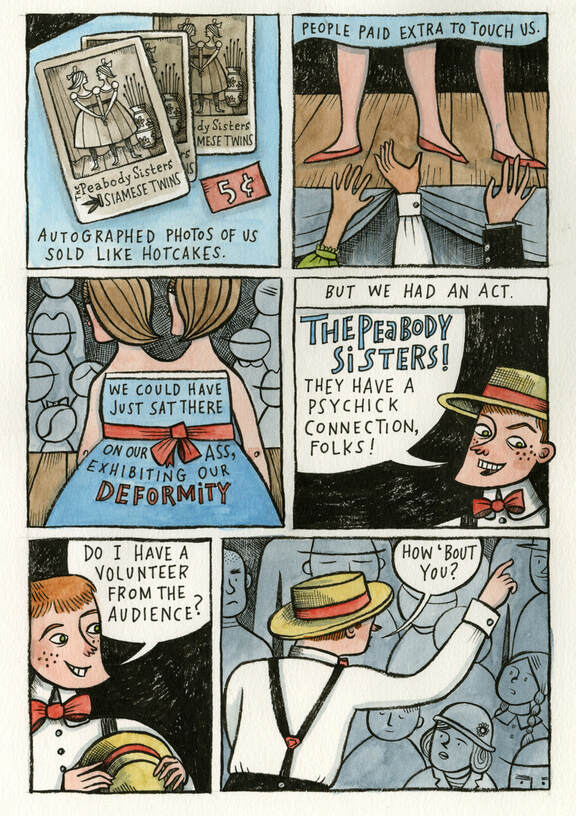

The Phantom Twin. By Lisa Brown. First Second, 2020. ISBN 978-1626729247, US$17.99. 208 pages. The Phantom Twin, a subversive romance set in a carnival freak show, risks creepiness, with a droll style that for me recalls the late Richard Sala (and, indirectly, Edward Gorey). The book treats sideshow freaks in a complex, sympathetic way; Brown captures some of the ironies of freakishness as performance, even as a means of limited agency, and depicts the world of the carnival as an everyday, intimate circle. That circle, though closed to rubes/outsiders, offers a chance at found family and romantic love. Despite what appears to be a straight romance plot, The Phantom Twin strikes me as implicitly queer, and treads on delicate ground, with matter-of-fact depictions of prosthesis, bodily spectacle, and gender ambiguity, as well as characters who, in some cases, embrace enfreakment and reject normate society. Briefly, the plot revolves around a pair of conjoined twins, Isabel and Jane, who perform in a sideshow until a botched separation surgery costs Jane her life, leaving Isabel, for the first time, to fend for herself. Isabel loses an arm and a leg in the process but gains the ghostly presence of her dead, but still very vocal, sister, who manifests as something like a phantom limb. (There’s a semi-Gothic air about all this that would make for a good Laika movie.) The carnival’s tattooed lady takes Isabel in, then introduces her to Tommy, who like Isabel is an artist – in his case, a tattoo artist. An interesting relationship develops, but then Isabel falls into a tryst with a muckraking reporter whose snooping ultimately threatens the whole carnival, which leaves Isabel cast out even by her fellow outcasts. The book’s ending has to resolve, all at once, the problems of thwarted romance and social ostracism – but Brown sticks the landing gracefully, with real boldness, and without too neat a fix. Brown clearly has a passion for the history and culture of the freak show; The Phantom Twin somehow channels Tod Browning’s Freaks while delivering a YA tale with, for me, a warm, affirming payoff. I dug it. My wife Mich, though, who read the book first, found it simply too creepy. We ended up talking about Brown’s harsh depiction of normate society (cruel, vicious, coldly transactional) and the threatening hints of gendered violence scattered throughout (too frank for that notional Laika movie). There were moments, on my first reading, that unnerved me; the world evoked here is quite dark. Yet love redeems it, somewhat – love, and the possibility of community among those deemed freaks. In sum, The Phantom Twin is gutsy and smart. It’s also elegantly drawn and colored, and eminently readable, carried along by restrained yet subtly varied three-tier layouts in classic style. In its embrace of bodily difference (and body art), it’s a courageous, insinuating graphic novel I look forward to re-reading. Many readers, I bet, will find it impossible to forget.

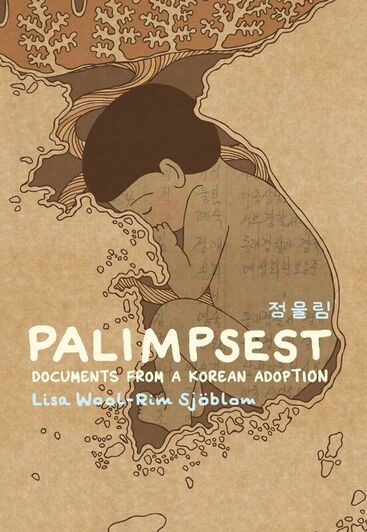

Palimpsest. By Lisa Wool-Rim Sjöblom. Drawn & Quarterly, 2019. ISBN 978-1770463301, US$24.95. 156 pages. This aggrieved and bitter memoir depicts the infuriating process of trying to dig up information about a transnational adoption. The author was adopted from Korea to Sweden as an infant — a transaction shrouded in misinformation — and Palimpsest recounts her trip to Korea to find her birth mother and piece together the whole story. This quest is thwarted again and again by contradictions, evasions, and outright lies. Much of Palimpsest’s narrative consists of correspondence, documents (usually reproduced in the author’s hand), and conversations — often confrontational ones, yet conveyed with a sort of unvarying graphic blandness. I found the book thematically compelling but also a tough, arrhythmic slog: more of a self-justifying argument than an evocative story about people, and hampered by an inexpressive, faux-naive style despite a beautiful overall aesthetic. Though the book talks about raw feelings, it consists mainly of constrained encounters between generically vague characters. The constant first-person narration is intense but not self-critical, and the other characters are mostly functionaries, save for a haunting depiction of the author’s birth mother. The story’s ending is powerfully sad, though Sjöblom's perspective on it struck me as stubbornly one-sided. I'm not sure that's a fair critique. After all, it's hard to gainsay an author's account of personal experience. Maybe I shouldn't. But I found the book's lack of self-reflection frustrating. Perhaps I’m just too used to self-deprecating, self-accusing autobiography? Palimpsest is something else. Still, I read it in one overtired late-night sitting despite its relative density (for a comic). The urgency of its political agenda kept me engaged. Its subject matter — the ethical and legal quagmire of international adoption — is tough and vital. Not a great comic in my opinion, nor a complex, self-knowing memoir, but a fierce expose. If Sjöblom's artistic choices sometimes damp down the book's power, what comes across is still raw: a cry of outrage and pain. Drawn & Quarterly provided a review copy of this book.

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed