|

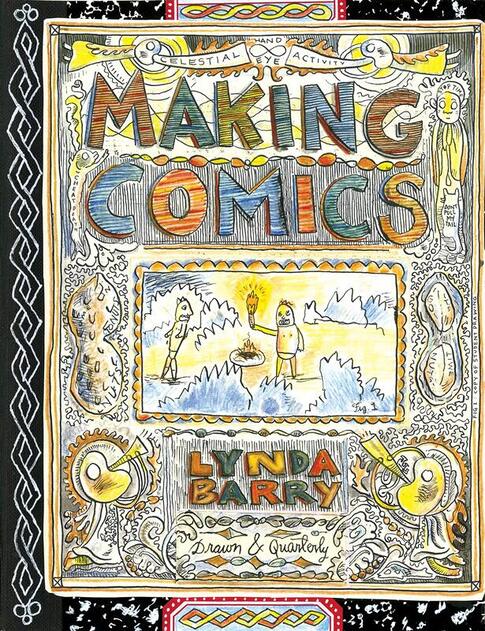

Despite hard times, I've been blessed with good comics reading, especially around this winter holiday season. I've contributed a list of favorites from 2021, along with commentary, to The Comics Journal's annual Best-Of, and what they have assembled is a great resource, well worth checking out (more than 20,000 words by close to thirty different critics). Meanwhile, the slideshow below offers an expanded list of personal faves, sans commentary, just FYI. I'm sure I've missed many great comics this year, as usual. Who can keep up? Of the thirty-two comics shown below, only six or seven are clearly "for" young readers. Some are decidedly adult. I note that, once again, I've listed more books (seven) from Drawn & Quarterly than any other publisher. I've also listed four from Fantagraphics. I've reviewed four of the titles below for SOLRAD: The Online Literary Magazine for Comics and three of them here on KinderComics. The books are listed alphabetically. Click on a book's cover to go to a webpage with more info about the book: A few notes about some of the above titles:

0 Comments

Man, I've been trying to catch up! What you see here is a short and personal list (though longer than the list I contributed to SOLRAD's Best) of new comics in print that kept me busy and happy, or productively on edge, in 2020 to early 2021. Most had 2020 publication dates, officially (I think). These twenty-five books or series are works I'll remember for a long time: books that felt urgent and/or mesmerizing to me and that fell into a bedside pile of "notable comics." I'm afraid these twenty-five do not include great webcomics, or short comics found outside of book or booklet form. Nor does it include certain books I might have admired had I been able to get to them. There is so much to catch up on, and so much more that I just can't include here, lest I make my head explode! Click on a book's cover to see a webpage with more info about the book. Note that many of these titles are not intended for children or young adults. PS. The two books that compelled me to redraw my mental map of comics this year were Dancing After TEN, by Vivian Chong and Georgia Webber, and The Sky Is Blue with a Single Cloud, a collection of comics by Kuniko Tsurita (1947-1985), masterfully curated and placed in context by Ryan Holmberg. Dancing After TEN, a collaborative memoir, overturns assumptions about the so-called autobiographical pact (as in, what exactly does the "auto" in autographics mean?), while also providing, with perhaps inevitable irony, powerful visual means of conveying one person's experience of what it meant to go blind. I think it's going to be a landmark among graphic memoirs depicting disabled experience. And the Tsurita volume, well, the surreal, elliptical, and haunting manga collected in it, the sheer beauty of the evolving artwork, the sometimes puzzling but always intriguing way it pulls me out of myself, and the superb contextualizing essay by Holmberg and Asakawa — it all adds up to an incredible gift: an important act of historical recovery as well as a bundle of great comics. BTW it's been an amazing year or so for scholar-translator-editor Holmberg, from The Man without Talent, The Swamp, and The Sky Is Blue with a Single Cloud, to his own personal scholarly/travelogue book, The Translator without Talent, to his reportage on antiracist comics activism in Graham, North Carolina. I first met Holmberg at (I think) the 2004 ICAF conference, and he's been expanding my understanding of comics ever since. Man, he deserves a medal. And I suppose Drawn & Quarterly, which has published translations of so many outstanding Japanese and Korean comics lately, is once again my Publisher of the Year. Thank goodness for them.

Class Act. By Jerry Craft. HarperAlley / Quill Tree Books, 2020. ISBN 978-0062885500, $US12.99. 256 pages. Billed as a “companion” to Jerry Craft’s Newbery-winning New Kid, Class Act is actually a direct sequel, following Jordan Banks and his schoolmates into the next year, but this time focusing less on Jordan and more on his friend Drew. The opening pages go to Jordan, and again his work as a budding cartoonist punctuates the story, in the form of comic strips notionally drawn by him—but Drew’s challenges, as a Black scholarship boy raised by a hard-working grandmother, soon take center stage. Drew’s pained awareness of class difference tests his friendships with Jordan and their affluent White schoolmate, Liam, and the plot tracks the awkward social negotiations among the three of them. Once again, Craft’s kids, brave and self-knowing, navigate the minefields of race and class, dogged by an inescapable sense of the things they don’t have in common; once again, their teachers are fumbling and oblivious. This time, Craft satirizes the inane efforts of their school, the tony Riverdale Academy, to extol “diversity”: teachers are dispatched to a conference called the National Organization of Cultural Liaisons Understanding Equality, and the school makes a failed effort to “adopt” a sister school whose working-class students of color don’t know what to make of Riverdale’s privileged, “bougie” atmosphere. As in New Kid, Craft observes all this in an amused, good-humored way, while never forgetting that difference can make all the difference. One tense scene depicts Jordan’s father being stopped by a White cop when driving in Liam’s posh neighborhood; moments like that affirm that Craft is playing for keeps, drawing out humor from real pain. Class Act, then, is smart and careful as well as high-spirited – though its story, I think, is more diffuse than that of New Kid, its stakes not quite as clear. (It would help to reread New Kid just before reading this one.) The book is busy and teems with in-jokes, including nods to comics and children’s book authors; sidelong gags are everywhere, to the point of distraction. More impressive is Craft’s diverse cast of distinctive, well-defined kids, many of whom get moments in the spotlight; they actually talk to each other, in courageous, meaningful ways, and Craft understands the subtle dynamics among them. You can tell he likes them. I confess that the art, with its jumbled, cut-and-paste style, clip-art elements, and CG backgrounds, put me off at first (I felt the same about New Kid). The work has an overbusy finish that mixes cartoony flatness with gradient coloring – an uneasy compromise. But Craft builds smart pages, and his socially engaged storytelling, once more, rings sharp, wise, and true. Dancing at the Pity Party: A Dead Mom Graphic Memoir. By Tyler Feder. Dial Books, 2020. ISBN 978-0525553021, $US18.99. 208 pages. Tyler Feder’s mother Rhonda Feder (née Hoffman) died of cancer when Tyler was nineteen, more than ten years ago. This memoir recounts Rhonda’s illness and death, her funeral, and the enduring sadness that has been part of Tyler’s life ever since—sometimes a still-raw, lacerating grief, sometimes a bittersweet nostalgia. That may sound just about unendurable: a self-pity party indeed. But what this book really does is pay homage to Rhonda Feder, evoke her particular, idiosyncratic self, and capture the way profound memories, very specific and odd memories that no one else could understand, arise unpredictably from quirky particulars and chance encounters. Yes, the book depicts, in fact enacts, grieving as a process, one that never quite ends, but it does so with verve, comic frankness, and surprisingly many laughs. In fact, at first, in the book’s opening pages, I wasn’t ready for Feder’s almost nonstop humorous flippancy, her many comic asides, satiric observations, and zingers. This sort of larking around in the shadow of death seemed like the very definition of Too Soon (although her mother died so long ago). To me, Feder’s approach at first felt too self-involved. But soon, very soon, the book crafts a precise portrait of Rhonda as a personality, lovingly remembered in all her quirks, the emotional, mental, and physical subtleties that made her who she was. Her eccentric liveliness, and that of her family, come through strongly, and Feder, in an unassuming and uncluttered style, balances deep sadness and irrepressible good humor, in a lovely, unforgettable tribute. Helpfully didactic at times (“Dos and Don’ts for dealing with a grieving person”), the book is mainly witty, personable, and compulsively readable—a remarkable example of how art, as Feder says, can “turn the crap into something sweet.” Little Lulu: The Fuzzythingus Poopi. By John Stanley, with Charles Hedinger, Irving Tripp, et al. Edited by Frank Young and Tom Devlin. Drawn & Quarterly, 2020. ISBN 978-1770463660, $US29.95. 276 pages. Lovingly edited, gorgeously designed, this second volume in Drawn & Quarterly’ deluxe hardcover Little Lulu series reprints more than thirty stories and strips, and a score of beautiful covers, that ran in the Dell comic book series circa 1949-1950. Written and laid out by John Stanley, these brilliant, economical, tightly wound comics were among the best of their time. They hold up well. Much has been said about Lulu as a feisty feminist icon who gets the drop on the sexist, obtuse, often mean-spirited boys in her neighborhood, and that’s true (the book’s introduction by Eileen Myles underscores that point); I was also struck, though, by the notes of human vulnerability and doubt in her characterization, by the signs of frailty and uncertainty that Stanley’s heroes often show. Lulu can be bullied, and Lulu can be hurt, but that makes her victories all the sweeter—she has real character. Stanley packs a surprising amount of human complexity into these condensed fables and gags. The tales are often absurd, sometimes satirical (such as “The Old Master,” a takedown of the art world), and always exquisitely timed, with gags and payoffs that depend upon very precise rigging. D&Q’s Lulu series is one of the best things happening in comics right now, even though the comics themselves are old. Drawn & Quarterly provided a review copy of this book.

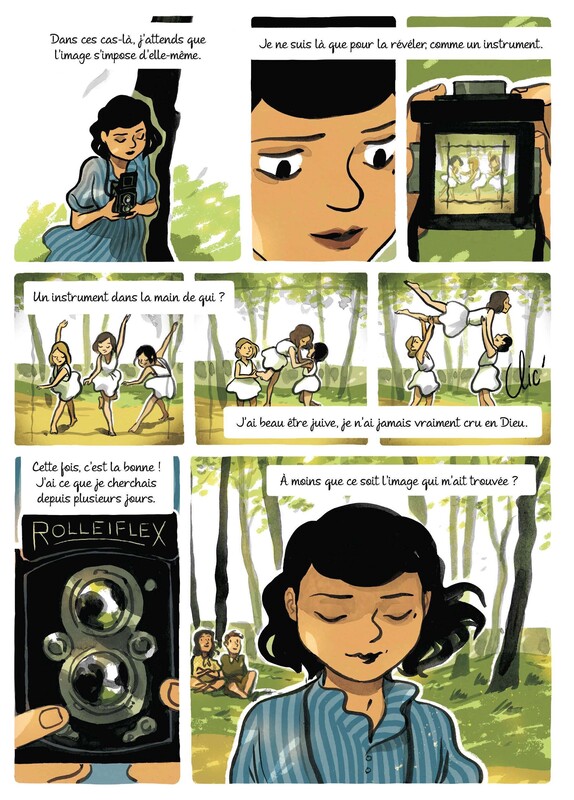

Catherine’s War. By Julia Billet and Claire Fauvel. Translated from the French by Ivanka Hahnenberger. HarperAlley, 2020. ISBN 978-0062915597, $US12.99. 176 pages. Catherine’s War is a finely shaded, beautifully cartooned, and engrossing book that ends much too abruptly. A historical novel stenciled from real events, it has been translated from the Angoulême Youth Prize-winning BD album La guerre de Catherine (Rue de Sèvres, 2017), which adapts Julia Billet’s prose novel of the same name (2012). Billet’s novel itself freely adapts, or at least draws inspiration from, the wartime story of Billet’s mother, Tamo Cohen, one of thousands of hidden children uprooted by the Holocaust: Jewish children sheltered from the Nazis, often in Catholic convents or among Gentile families. In real life, Tamo Cohen did attend the Sèvres Children’s Home (in fact a progressive, student-centered school), as does the protagonist of this novel, Rachel Cohen, and she did flee the Nazis, and she was renamed to pass as a Gentile, just as Rachel here is renamed “Catherine Colin.” But, as Billet admits in her notes, the story of Catherine’s War “remains a story”—a historical fiction interwoven with truths. Billet imagines Rachel/Catherine as a young photographer whose images of WWII are successfully exhibited in a Parisian art gallery soon after the war (an exhibition that replays many experiences depicted earlier in the book). Further, Rachel’s narration, implicitly, comes from her journal—so, she is an artist in words as well as pictures. In that sense, Catherine’s War becomes a Künstlerroman as well as a wartime tale of life on the run. Thematically, it reminds me of books like Whitney Otto’s ensemble novel Eight Girls Taking Pictures (2012), a fictionalized biography of eight women photographers, and comics like Isabel Quintero and Zeke Peña’s Photographic (2017), a YA biography of famed Mexican photographer Graciela Iturbide. Reframing Tamo Cohen’s story within the history of photography, Billet casts her mother, or rather Rachel, as a visual witness to the terrors of war. Armed with a Rolleiflex (like Robert Capa – or Annemarie Schwarzenbach?), the fugitive Rachel/Catherine becomes a chronicler as well as autonomous artist, even as she rushes from one shelter to the next to evade the Nazis. For all that, Catherine’s War is not explicitly violent. Though fear is ever-present, intimations of war and Holocaust are discreet; we never see the dreaded roundups or camps, or combat (though overheard dialogue among Resistance fighters does imply sabotage). The point of view is limited to what a child in hiding, pretending to live out her normal life, might have witnessed. Trauma is suggested by the extent to which Rachel and other young people help each other cope with it. The various children depicted (the story begins at the Sèvres home, and Rachel most often travels with other kids) are wounded by the shocks and partings they have to endure, yet they are resourceful, brave, and unselfish—not to the point of absurd angelic idealization, thank goodness, but in a tense, believable way. (Billet’s trust in young people mirrors the radical teaching philosophy of the Sèvres school.) Multiple scenes depict the challenge of trying to keep cover stories straight, the distrust stoked by constant surveillance, and the dread of giving the game away. Yet the novel is so discreet that it takes Billet’s endnotes to flesh out the terrible context of WWII. Those notes clearly anticipate a young audience, and I note that the book is blurbed by a notable writer of children’s nonfiction, Susan Campbell Bartoletti, whose work (Hitler Youth, Kids on Strike!, etc.) often extols young people’s activism and recounts harrowing historical facts with candor but also due sensitivity. Decorous would describe this book’s approach: from the story’s quiet hinting, to Claire Fauvel’s rippling brush-inking, gentle watercolors, and borderless panels, to the prim digital lettering (by David DeWitt). A genteel aesthetic overlays everything, conferring delicacy despite the nightmarish world evoked. What makes all this work is Fauvel’s patience, empathy, and attention to detail: from the opening pages, she tracks Rachel and the other characters with exquisite care, and their feelings, both spoken and unspoken, register honestly. Fauvel’s visual storytelling, if understated, is fluid and confident, moving characters about gracefully and capturing unwritten nuances in most every scene. She really cares about these characters. In short, Catherine’s War is smartly laid out, superbly drawn, and piercing. (For insight into Fauvel's process, and the book's production, see Billet's VanCAF presentation from last spring: a slideshow and talk captured on video, subtitled in English.) Not everything in the book works. There are moments where the book seems determined to spell out, rather than suggest, its messages—passages that seemed forced. In particular, a postwar scene depicting the ritual shaming (head-shaving) of French women accused of Nazi collaboration seems underdone; it doesn’t explain what’s at stake, and Rachel’s rejection of the shaming mob doesn’t register (though Billet’s endnotes work hard to underscore the didactic point). Also, as the book accelerates toward its end, things happen rather too fast. Both a crucial relationship and the postwar arc of Rachel’s life are sketched in abruptly over the last couple of pages. (It turns out that there’s a sequel, published in French in 2020, so perhaps the ending was meant to be a springboard?) When I turned the final page, I felt as if I was still in midair. That said, the gnawing dissatisfaction I felt got me to reread the book, which sharpened my appreciation of Fauvel’s subtle artistry. As I say every so often, I’d be glad to read more.

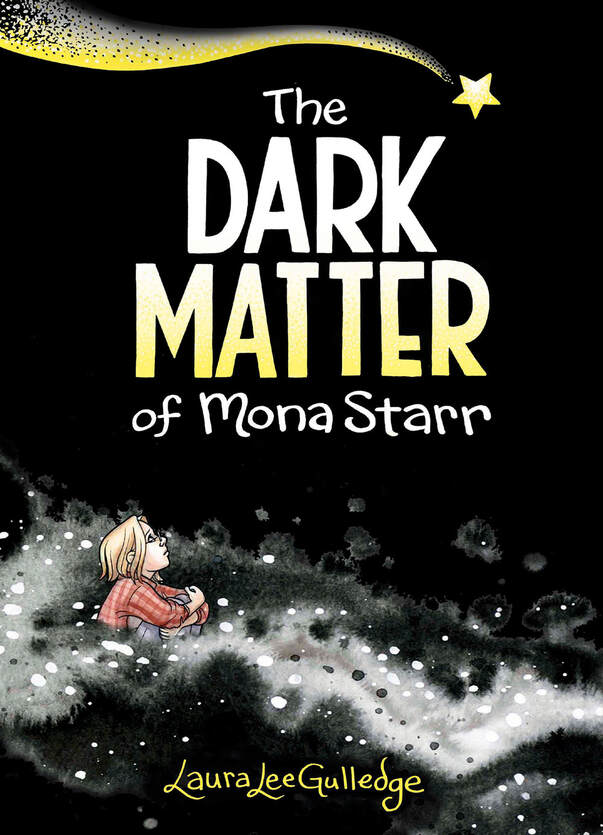

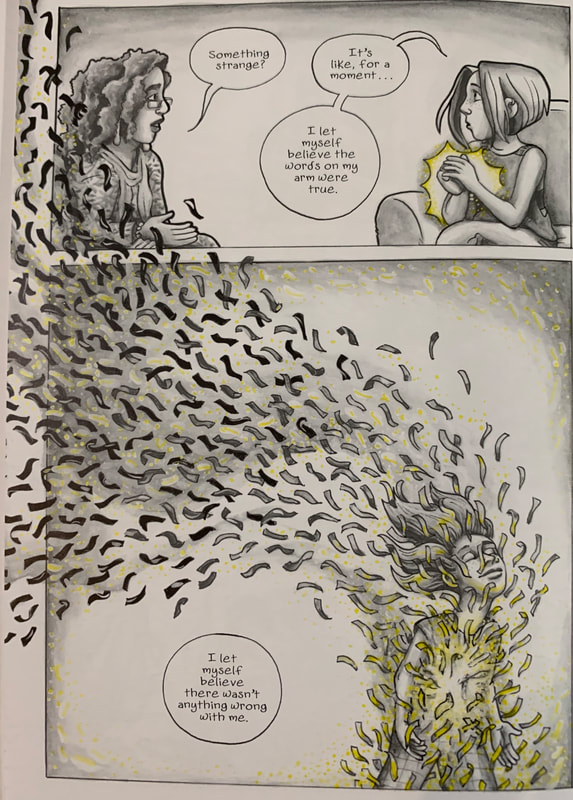

The Dark Matter of Mona Starr. By Laura Lee Gulledge. Amulet Books/ABRAMS, 2020. ISBN 978-1419742002, $US14.99. 192 pages. In this semi-autobiographical novel, Mona, a high-schooler and artist who suffers from depression, undertakes a self-study to better understand her needs and triggers and fashion a "self-care plan." Though a loner by temperament, she learns to think outside of herself and recognize loving relationships and creative collaboration as important resources in her life. With the help of her counselor, parents, and friends, Mona chooses an ethic of community and participation, sharing her aesthetic gifts and inspiring others to do the same. Looking beyond herself, even as she honors her own needs, enables her to engage the world on different terms and, to some degree, counteract her depression. The novel climaxes with a community art project in which Mona and her self-styled "Artners," Aishah and Hailey, invite many of their fellow high-schoolers to collaborate in a spirit of loving community. The story's keynotes are self-love, self-advocacy, and willful optimism, and its last word (literally) is hope. Like Ellen Forney's celebrated memoir Marbles, this novel hovers between raw personal storytelling and hortatory self-help, with chapter headers that give emphatic advice, such as Turn emotion into action and Break your cycles. Author Gulledge shares her own self-care plan in the back pages, and her notes confirm that Mona Starr is indeed based on her. Artistically, the book is wildly expressive; the pages brim with visual metaphors of depression and elation, self-isolation and self-release, artistic engagement and pure joy. Depression, Mona's so-called dark matter (her mom is an astrophysicist), appears as swirling black clouds, faceless anthropomorphic demons, dark waters, black flames, and gripping hands. Moments of self-realization and delight are accompanied by stars and streaks of bright yellow: the one spot color in Gulledge's otherwise black-and-white, or rather grayscale, aesthetic. Mental landscapes — vast oceans, deep, dark wells, and the swirling cosmos — convey Mona's ever-shifting inner state. Consensus "reality" is perfused with expressionistic symbolism, and many pages leave behind real-world settings altogether. The sheer profusion of visual symbols reminds me of, say, Iasmin Omar Ata's Mis(h)adra (a semi-autobiographical account of epilepsy that is likewise braided with graphic devices signaling the protagonist's inner state). Gulledge's figures, word balloons, and symbols routinely break out of her panel grid — in fact, there is not one page that obeys a strict, unbroken paneling — and the layouts are ceaselessly dynamic. Immersive full bleeds are frequent. In short, the book is a staggering exercise in expressive drawing and page-making. Story-wise, though, Mona Starr feels a bit thin and undeveloped to me. Despite hints that other characters may also struggle with mental illness or disability, and despite the plot's emphasis on seeking "help" and community, the novel feels very much absorbed by Mona's mental state and Gulledge's exhortations to embrace one's creativity. The book feels idealized, dreamy, and self-involved; Gulledge's artistic bravura, the sheer busyness of her pages, doesn't let the depression seem real. Everything is couched in terms of artistic therapy, self-study, and a self-improvement "project." Mona's counselor is introduced at the start, before Mona's depression has manifested narratively, and the greater context is emphatically reassuring. Much of the book consists of poetic self-reflection, heightened by the overflow of visual metaphor, as if in confirmation of Mona's creative "genius" (a personality test labels her "the potentially unstable visionary type"). Familial and social complexity take second place to exploring Mona's state of mind through ravishing visuals. The singular focus on Mona's feelings and self-conception would probably be smothering in bare prose; only Gulledge's ecstatic imagery gives the story life and depth. The result is heady and interesting but, I'm tempted to say, less novelistic than an exercise in didactic self-help. Somehow, the book manages to be at once lyrical, spectacular, and a confidently crafted exercise in comics, yet also frustratingly under-done, as if Gulledge couldn't quite take distance from what is, after all, a kind of exhortative autofiction. But here's the deal: I enjoyed reading Mona Starr, and it has moments that, on re-reading, still get me choked up. The book's conclusion is calming and gratifying, and I cannot deny Gulledge's hard-won insight. I am pretty sure that some readers will be affirmed, and perhaps even forever changed, by reading this book. I wouldn't recommend Mona Starr for complex, intersubjective storytelling, but will remember its powerful evocations of feelings and states of mind, as well as Gulledge's confident artistry.

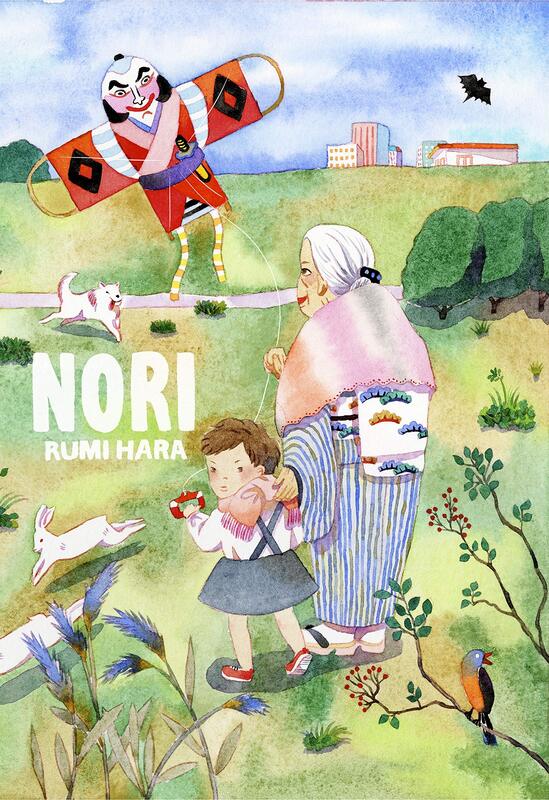

Nori. By Rumi Hara. Drawn & Quarterly, 2020. ISBN 978-1770463974, $US24.95. 228 pages. Collecting a series of minicomics begun in 2016. I regret not reading Nori sooner. It’s great: a poetic, beautifully observed portrait of one Japanese girl’s (and her grandmother’s) life, unforced, elliptical, and deeply personal. Sadly, this sort of evocative and searching book often gets dismissed by proponents of children’s books as too confusing or difficult (I know—I’ve been in quite a few conversations like that). Rumi Hara’s tale, seemingly semi-autobiographical, recalls a mid-1980s Japanese girlhood of a particular kind, in a scruffy, organic style that, for me, calls to mind Debbie Drechsler, early Lynda Barry, or Henrik Drescher. There's a similar fascination with texturing, in this case achieved through a versatile dry-brush technique that lends mood and specificity to each scene (Hara reportedly works on handmade paper, and her surfaces have a kind of nap, or nubbliness, a delicious roughness). Graceful use of a different spot color in every chapter imparts added flavor and also an overall sense of structure. I found Hara’s pages a bit disorienting at first—so rich are they—but man are they beautiful, and transporting. There are enchanting spreads here that just carry me away. Noriko, or Nori, an energetic girl of about four or five, is never disciplined out of her own free self, and remains, throughout, stubborn and even volatile, at times perhaps a bit of a pill, but really a delight. Her spirits are never sacrificed for some insufferable didactic point about maturing or becoming less of a challenge to grownups. Thank goodness. Nor does she just stand in for “childhood” as a vague state of freewheeling, unworldly innocence. She and her world are too particular for that—again, thank goodness. I grew to love this specific girl and her patient, but not over-idealized, granny, who in effect mothers Nori while the girl’s parents are busy working, working. This is a soulful book, empathetic and unpredictable, without obvious designs on the reader. Hara's storytelling takes an outside observer’s view most of the time, not giving us too-easy access into Nori’s (or anyone’s) thoughts, and sort of ambling from one thing to another, or so it seems, without obvious crises or problems to solve. But then bursts of dreamlike fantasy, brief and powerful, intervene, showing Nori's thoughts as she communes with her environment or works out her own fantastical logic. At those moments, Hara takes us in deep, but without ever showing her hand. We get glimpses of a magical but not overly sweet inner life; there's a touch of the uncanny as well (Hara says, "I like stories that have a little creepiness to them, like old folk stories that are simple but mysterious"). And as it turns out, the stories, which at first seem to have a shaggy-dog waywardness about them, are insinuating, carefully crafted, smartly rounded and complete, with levels and levels of implication and (if you care to reread and ponder) symbolism. Seeming threats turn into affirmations; the uncanny becomes lovable, yet never saccharine. I particularly enjoyed the long, ambitious story in which Nori and granny unexpectedly win a trip to Hawaii and have a wonderful, though complicated, visit there. Writing and art are both electrifyingly good here. I didn't get to read this, one of the best books of 2020, until a week into 2021. For shame! Most highly recommended. Drawn & Quarterly provided a review copy of this book.

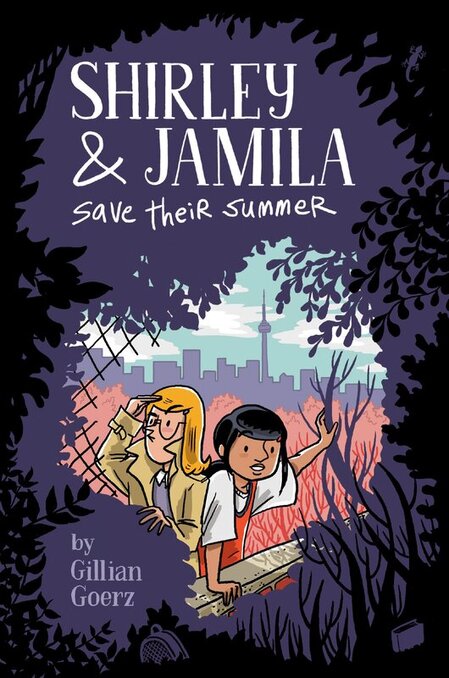

First, a brief personal note:You might think that being in pandemic lockdown would mean reading lots of comics, and with relish. I had thought so too. But I have to confess to feeling adrift lately; if anything, I may have been reading fewer comics than usual. I frankly don’t understand this, and it makes me sad, but there it is. COVID seems to have wrought havoc with my reading life, and many of the talked-about comics of 2020 are still unknown to me. Usually, I look back on the year in comics with a surplus of terrific new titles that I have trouble choosing among. Bounty is my normal. This year, though, I've had a hard time envisioning a Best-Of list for KinderComics. I've been down in the dumps about this for a bit. That's why it is such a pleasure to have contributed, in however small a way, to SOLRAD's list of The Best Comics of 2020. This multi-authored listicle is an education to me: a reminder of how widespread, diverse, and unpredictable comics can be. SOLRAD, "a nonprofit online literary magazine dedicated to the comics arts," has just celebrated its first anniversary, and it's a great site, an essential stop for readers who care about innovation and artistry in comics. I'm glad to have done anything for them, and very glad to have their Best-Of list as an antidote to my blues. Please go check it out! And now, back to what KinderComics usually does: Shirley and Jamila Save Their Summer. By Gillian Goerz. Dial Books, 2020. ISBN 978-0525552864, US$10.99. 224 pages. I like this sunny middle-grade mystery, which follows a pair of mismatched but true friends who investigate a theft at a local swimming pool. It’s the sort of thing that could hit the spot for fans of Nancy Drew, Encyclopedia Brown, or Nate the Great. The setting appears to be suburban Toronto. Shirley is a super-observant Holmesian kid detective, also a social outcast: a tightly wound nerd-savant figure, perhaps implicitly an Aspie (the characterization seems to lean in that direction). Jamila, the novel’s true focal character, is an aspiring athlete, eager and restless, loved by her family yet perhaps overshadowed by her older brothers. Jamila and Shirley, temperamental opposites, need each other; both girls chafe against the protectiveness of their moms and are looking for ways to buy a bit of freedom over the summer. They team up to break out. Shirley is White, while Jamila comes from a South Asian, perhaps Afghan or Pakistani, ostensibly Muslim family; the girls' neighborhood is convincingly diverse. We learn much about Jamila’s family, the dynamics of which are deftly established, with discreet cultural cueing and an easy, lived-in complexity. (I particularly liked the characterization of her mother, a subtle and telling depiction.) Despite some early signs of tentativeness (say, in layout and balloon placement), Goerz crafts a tightly constructed, unflagging, engaging story, one that hopscotches confidently from chapter to chapter, evokes a credible social milieu, and, best of all, vividly imagines what turns out to be a large repertory company of characters. This is, in the end, a sure-handed, well-edited, handsomely cartooned first graphic novel for Goerz: in sum, a cool book. It looks to be the first volume in a projected series; I'd happily read more.

Despite the ravages of COVID, I feel optimistic about my field, comics studies, and glad to be part of it. Important, eye-opening research continues apace, and my understanding of the field keeps getting bigger (which is to say that I keep getting challenged, in invigorating ways). The scholarly institutions I’ve been part of are doing what they can to bring communities together in spite of the pandemic. Academic conferences, independent comics festivals, and large-scale comic-cons have offered virtual programming this past year, so that life and study at home don’t seem quite so lonesome. I’m particularly happy to see the International Comic Art Forum’s slate of monthly virtual events, still ongoing, and the call for next summer’s Comics Studies Society conference. On a personal note, this year saw, at last, the publication of a long-term project of mine, Comics Studies: A Guidebook, a classroom-ready anthology co-edited with Bart Beaty (and published by Rutgers University Press). Bringing this book into the world took many years, but I'm proud of the results: essays by twenty scholars on the history, form, genres, production, and reception of Anglophone comics. These essays succinctly explain fundamental issues in the comics studies field, crystallizing complex questions, if I may say so, in ways that no book has done before, and often with real conceptual originality. I thank our contributors for their steadfastness, patience, and brilliant writing; the life of the Guidebook is in their essays. If you're a student or teacher of comics, I hope you'll check our Guidebook out. Again speaking personally, I had the pleasure to contribute to another comics studies volume this year, Kim Munson's Comic Art in Museums (published by the University Press of Mississippi), a groundbreaking collection focusing on the exhibition of comics in museums and galleries. If you want to know more about how comics came to be exhibited and recognized in the art world, then this book can give you a grounding. The history that Munson and her contributors lay out is longer and more complex than you might expect. (I am honored to have two pieces in the book, and to have curated the 2015 Jack Kirby exhibition that is the focus of several pieces.) What follows is a handful of comics studies books that I'm currently reading, books that I find particularly exciting at this moment. This is not meant to be a best-of for 2020, since, goodness knows, I've had trouble keeping up academically during the long lockdown (and there are new books that I haven't had a chance to dive into yet, such as Anna Peppard and company's Supersex: Sexuality, Fantasy, and the Superhero, or Frederick Luis Aldama et al.'s massive Oxford Handbook of Comic Book Studies). These are just a few of the books that recently struck me as expanding the boundaries of the field: Sean Kleefeld, Webcomics (Bloomsbury). Eszter Szép, Comics and the Body: Drawing, Reading, and Vulnerability (The Ohio State University Press). Disclosure: I co-edit, along with Jared Gardner, Rebecca Wanzo, and acquiring editor Ana Jimenez-Moreno, the OSUP's Studies in Comics and Cartoons series, which published Szép's book.) Gwen Athene Tarbox, Children's and Young Adult Comics (Bloomsbury). Rebecca Wanzo, The Content of Our Caricature: African American Comic Art and Political Belonging (NYU Press). Paul Williams, Dreaming the Graphic Novel: The Novelization of Comics (Rutgers UP).

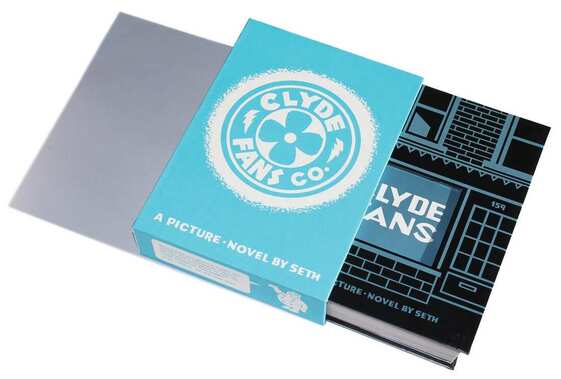

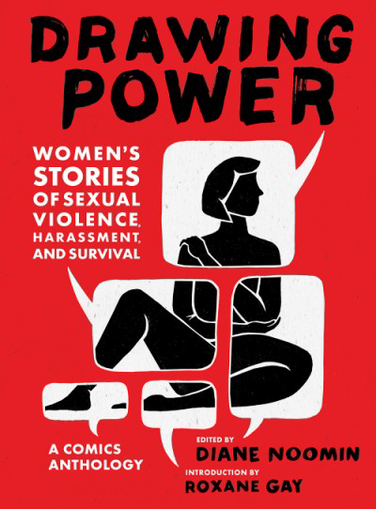

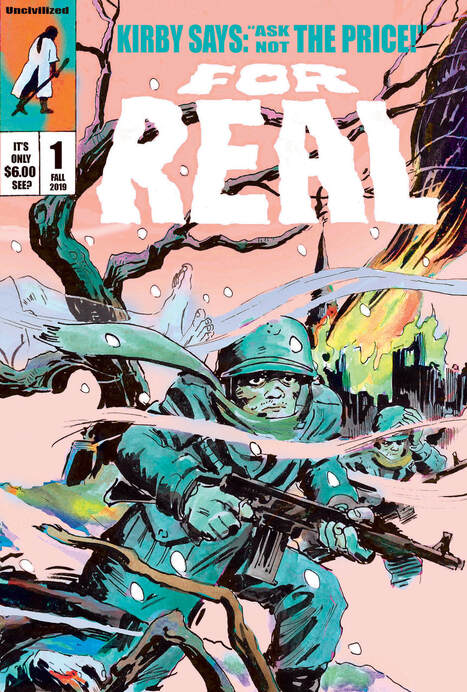

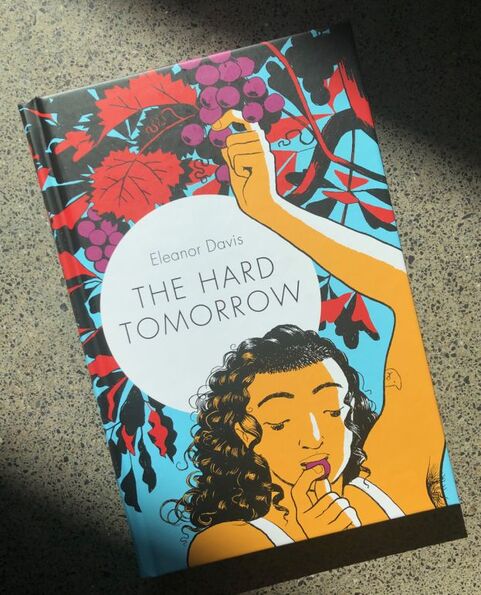

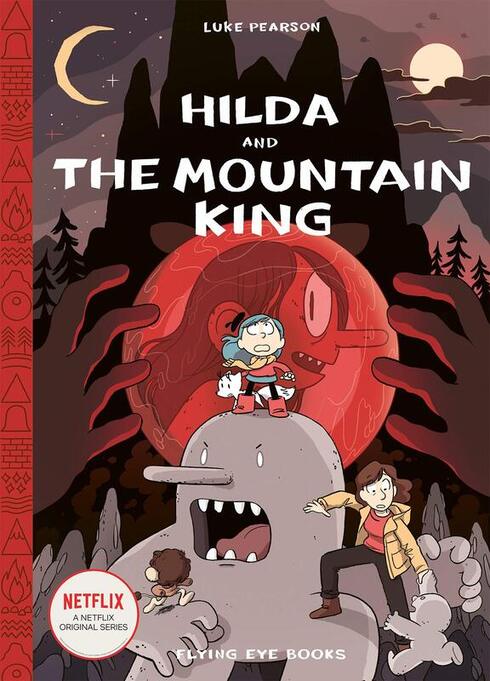

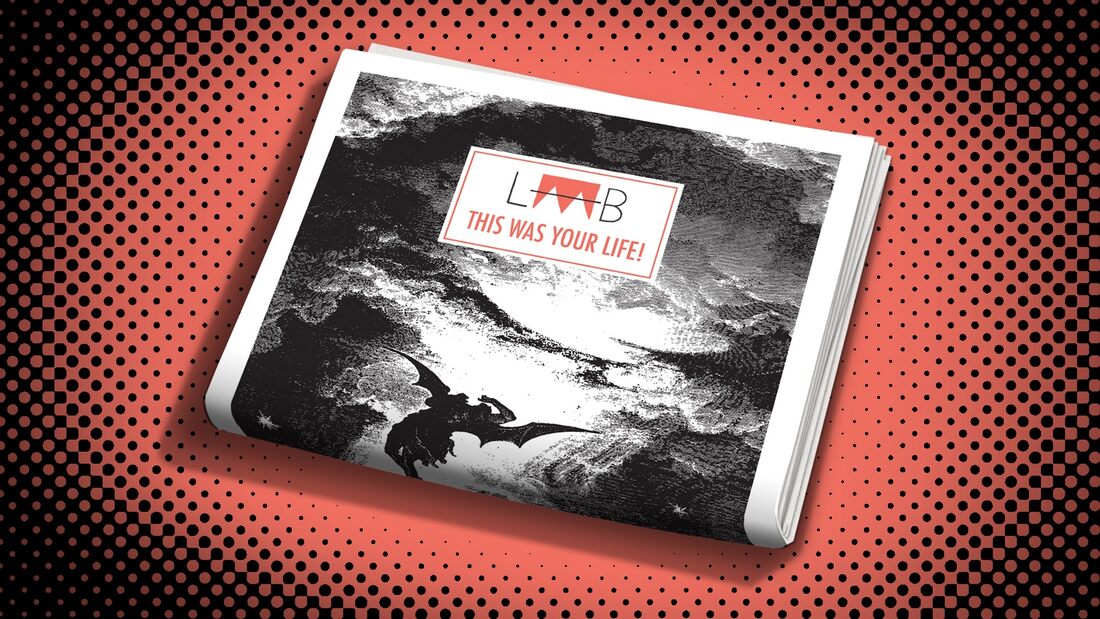

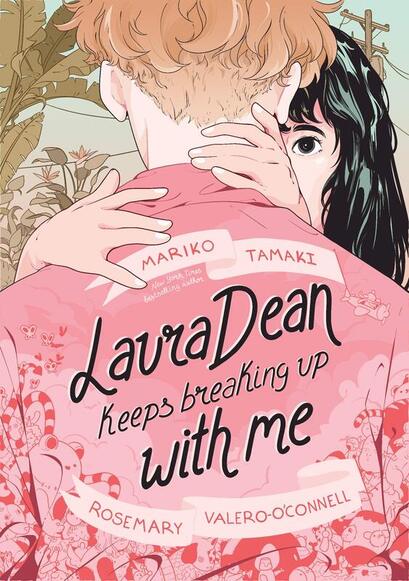

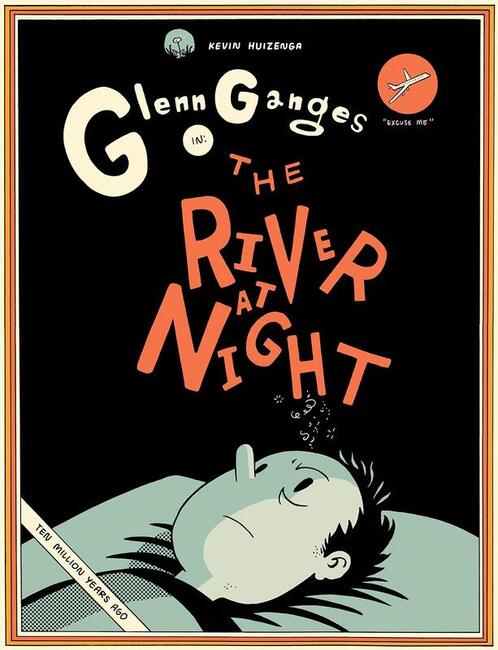

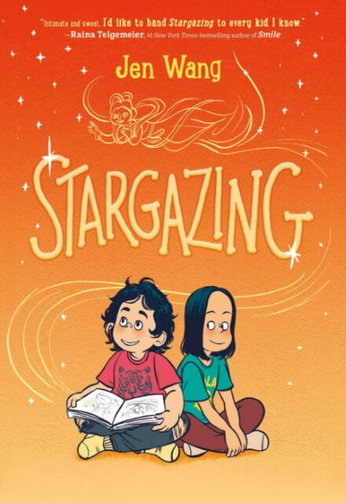

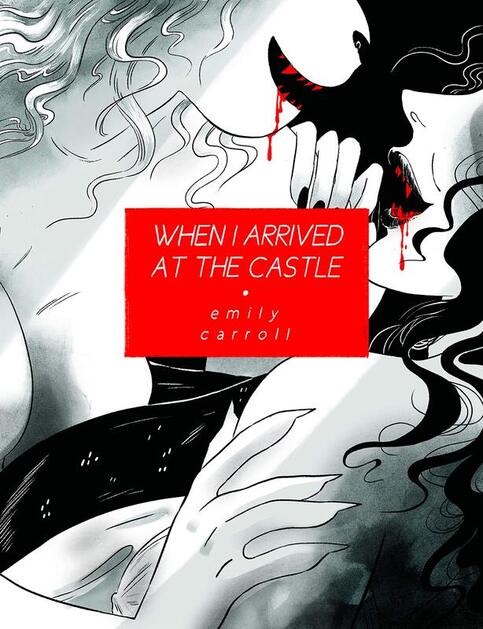

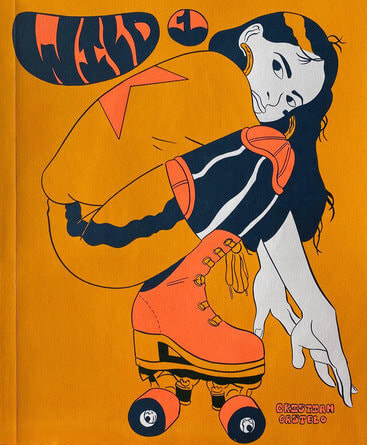

I’m late to this party, I know. By now, I’ve been arguing with best-of-year and best-of-decade lists for weeks. I gotta admit, keeping up with new comics (both those I choose to cover on KinderComics and many others) is a full-time gig that I don’t quite have “full time” for. Truth to tell, I’m still catching up with many talked-about books from this past year (e.g. work by Ebony Flowers, Molly Knox Ostertag, Frank Santoro, and Chris Ware). The patchiness of my reading matches the patchiness of this blog over the past year. Due to academic scheduling pressures, I published nothing substantial here between my best-of list for 2018 and late July. That was painful. I finally got in a few posts in the late summer, then returned more decisively in October, finishing out the year with a string of reviews that made me feel better. I had thought that I might need to shutter KinderComics entirely, but the sprint I was able to do late in the year has convinced me that I should stick around. Thank goodness. I love doing this work. Below (in alphabetical order by title) are the new English-language books of comics that made the strongest impressions on me in 2019. Some I’ve reviewed on this blog. I’ve kept this list narrow, excluding translations, webcomics, reprints, and most periodical comics for the sake of expediency. As usual, the list reflects my split identity as both a children’s comics advocate and a lover of alternative and art comics and small-press work (not everything here is meant for young readers). I hope to follow this post soon with a best-of-decade list and some reflections. The 5 Worlds series, a planet-hopping space opera for young readers, at last finds its rhythm and delivers a fairly transparent but still affecting allegory about how to maintain hope in dark times. This has always been a wildly ambitious series whose reach exceeds its grasp, but The Red Maze won me over. I reviewed this here on KinderComics at the end of July. A beautiful, mystifying graphic novel in which two young women, fugitives, drive through a fantastical version of West Texas, pursued by shadowy figures and their own traumas and losses. Perhaps not Walden's strongest story, but a transporting experience, gorgeously drawn and colored. I reviewed this here in early November. Razor-sharp satire and oozy body horror collide in a wickedly funny fable about gentrification. I reviewed a beta version of this novel on the Comics Studies Society's Extra Inks blog way back in Feb. 2018. So glad to see it out in the world now. Seth's long-simmering novel of failed ambition, social withdrawal, and psychological isolation, now collected. Chilling, in the end. I expressed ambivalence about this book in my contribution to the Comics Journal roundtable, back in June, but, damn, it is a monumental, haunting work. Reviewed here very recently. What a resource! An anthology of wrenching work, and a project of real artistic courage. Inevitably uneven in terms of professional finish, but so, so powerful. So many very strong emotions have been funneled into this book, and so many different ways of delivering hard truths. Far from despairing, the book is, as promised, a power source -- and a timely, necessary intervention. James Romberger's biographical fiction about the great Jack Kirby: an understated yet moving comic book, short but full, light years away from the usual thoughtless evocations of Kirby as "king." Great cartooning and real insight. I reviewed this on my Kirby studies blog in October. I'll join the chorus of voices hailing Davis as the cartoonist of the decade. I'm not sure what to think of this dystopian near-future fable, but I can tell you that I literally shook while reading it, and stared at its final pages, stunned. I so want to write more about this series and its creator here on KinderComics. The latest and most complex of the Hilda albums, and a perfect capper for everything that has come so far. Breathlessly exciting, as usual; also sensitive, subtly moral, and an unexpected broadening of Pearson's world. This has been my favorite new children's series of the decade. Finding the first issue (#0) of this, Ronald Wimberly's et al.'s annual broadsheet anthology, was one of the highlights of my CALA 2018 experience. A year later, finding the second issue (oddly, it's called #4) was one of the highlights of CALA 2019. A brilliant, troubling collection of giant-sized comics (Wimberly, Hellen Jo, Emily Carroll, Richie Pope, Ben Passmore, etc.) and provocative essays and arguments. This particular issue concerns environmental catastrophe, necropolitics, and horror. I came late to this, at year's end. I wish I had reviewed it. A matter-of-factly queer YA story of high school romance, friendship, and the struggle for moral agency, this novel is distinguished by a thousand grace notes of observation and expression. A bodily and culturally diverse cast of characters dances a complicated social dance, courtesy of nuanced dialogue and cartooning that makes them feel wholly real. Wise as well as useful, Beautiful as well as strange. Try it on for size; it might change the way you feel about your own ability to create. See my event report from mid-October. I happened to run into Kevin Huizenga at CALA 2019, and stood there like a tongue-tied idiot, trying to think of novel ways to gush. I love the thoughtfulness and rigor of his cartooning, and the formalist inventiveness too. Those qualities come through in this philosophical novel about an insomniac's sleepless night of contemplation and mental journeying. It feels like a super-dense lesson in thinking about thinking. Or simply a lesson in living? I reviewed this here in early December. It's a graceful and moving evocation of friendship among two outwardly mismatched but deeply bonded Chinese American schoolgirls. A fresh new approach to what is rapidly becoming a familiar type of graphic novel, delivered by one of America's best comics artists and storytellers. Lovely and rather terrifying: a ripe, rapturous erotic horror story in a deluxe package, formally daring, disorienting, and like no one else's work. NSFW, but to hell with safe. Another CALA 2019 discovery: cartoonist Cristian Castelo and his colleagues in the Bay Area comic artists' collective Freak Comics. They had so many good things at their table, I could hardly decide what to get, but I settled on the above book: an oversized, riso-printed beauty that collects and revises the first three chapters of Castelo's ongoing series Wild, a period fantasy about mid-1970s high-school roller derby girls. It's drawn in a voluptuous style that for me recalls both Paul Pope and Los Bros Hernandez. Castelo's outsized characters fill the pages and demand attention; this is gutsy cartooning, full of sensuous, heroic figures. And the coloring and production are enough to make me swoon. I can't wait to read more from Castelo and his Freak colleagues. PS. For the record, the new comic book serials that I found most interesting in 2019 were Walker, Brown, and Greene's Bitter Root and Wilson and Ward's Invisible Kingdom. The corporate superhero comics I enjoyed most were Bendis, Derington, and Stewart's six-issue romp Batman: Universe and Ewing and García's cosmically posthuman Immortal Hulk #25. I also dug Tradd Moore's trippy art on Silver Surfer: Black, though I wasn't won over by the book's writing. Among serials, I am currently interested in Craig Thompson's autobiographical Ginseng Roots and John Allison's droll comedy about religion, witchcraft, and community, Steeple. I am behind on faves like Saga, Paper Girls, and Monstress, but determined to catch up...

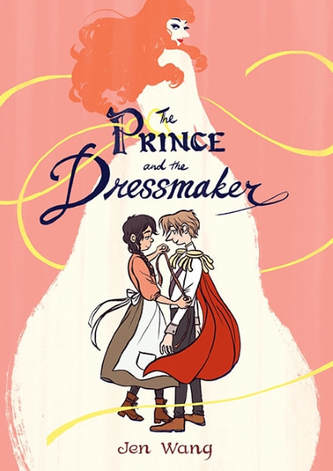

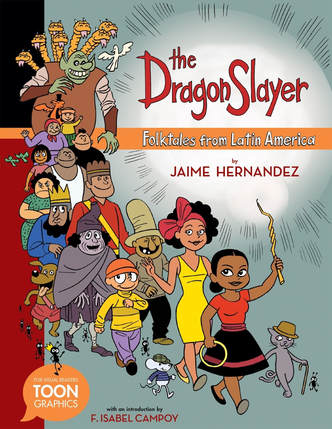

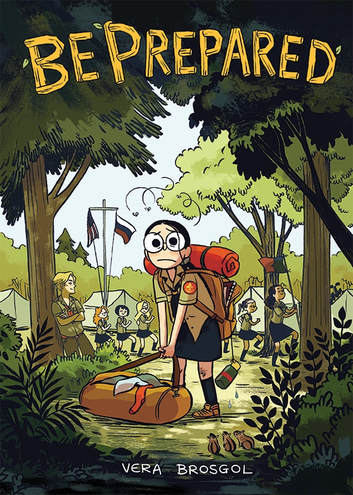

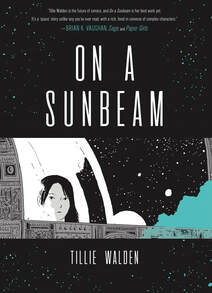

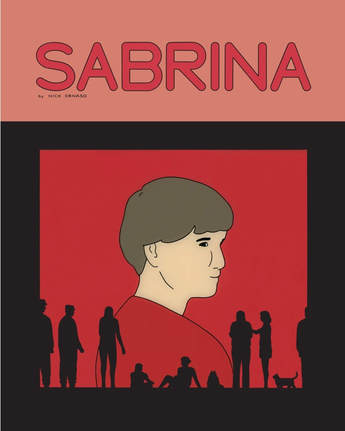

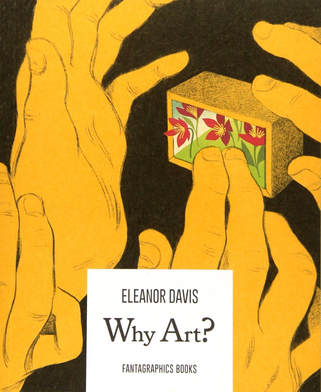

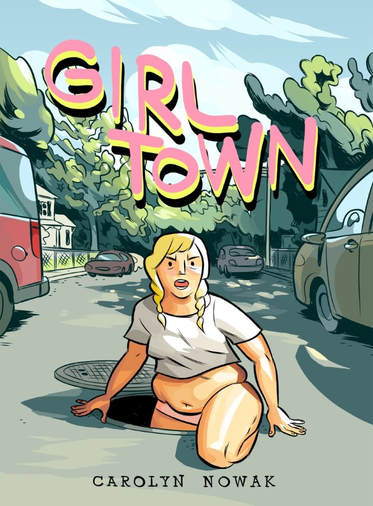

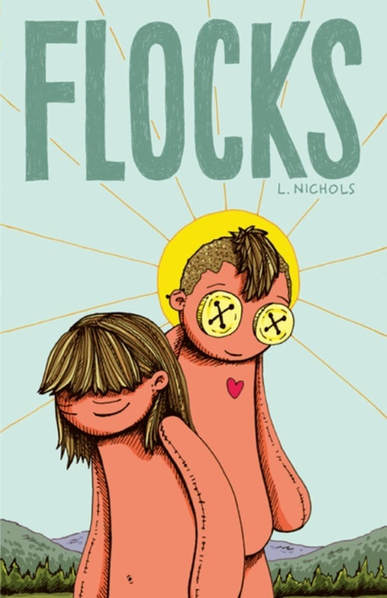

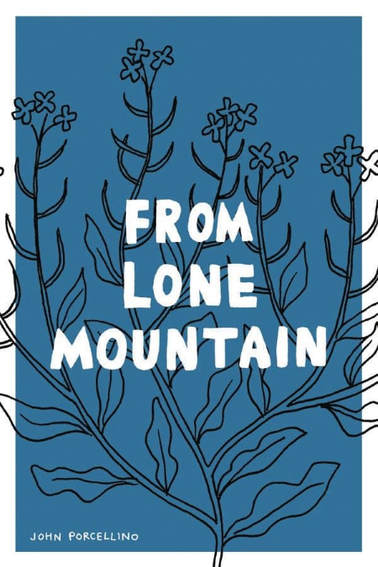

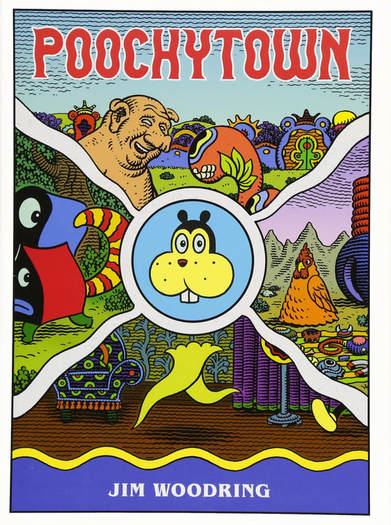

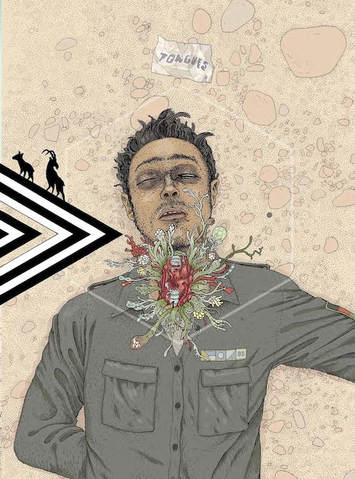

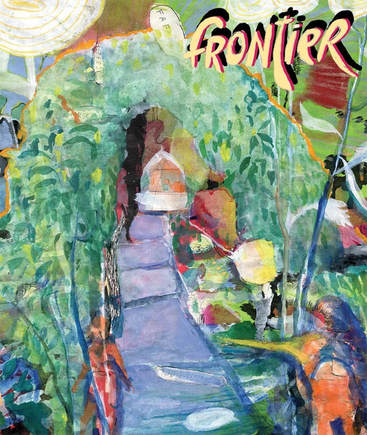

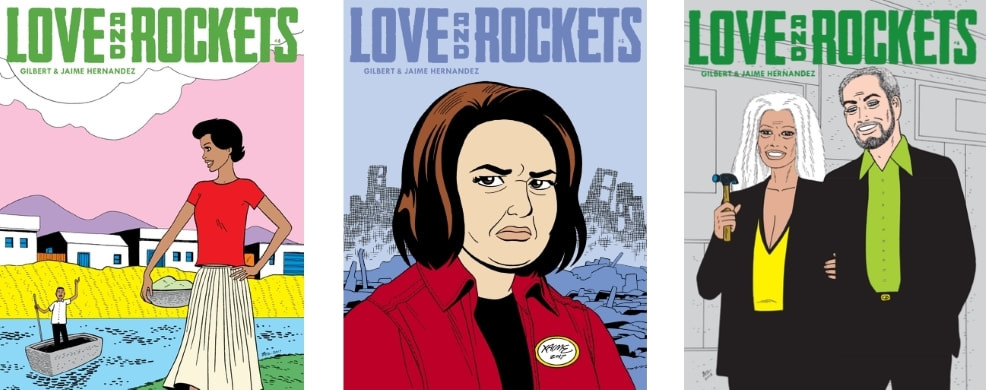

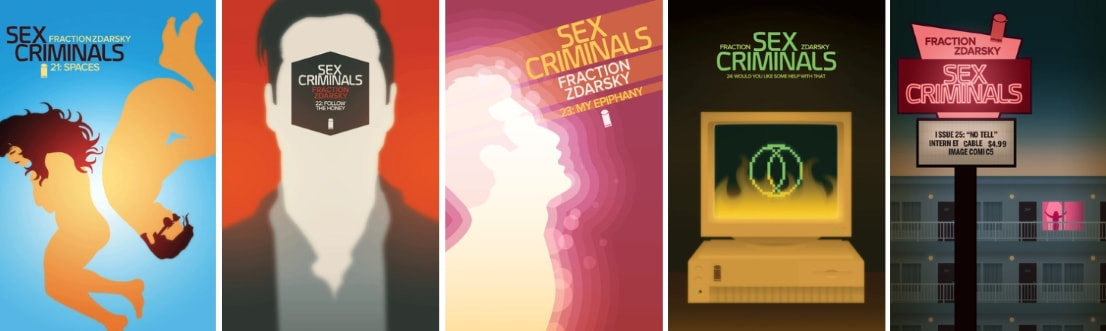

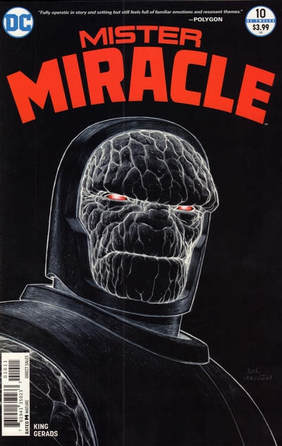

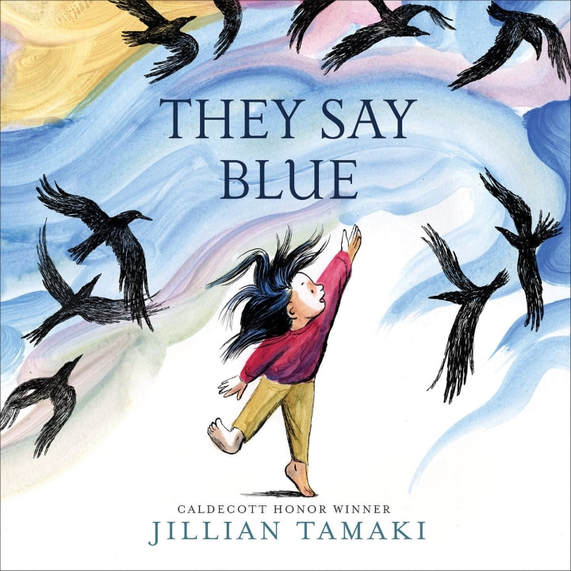

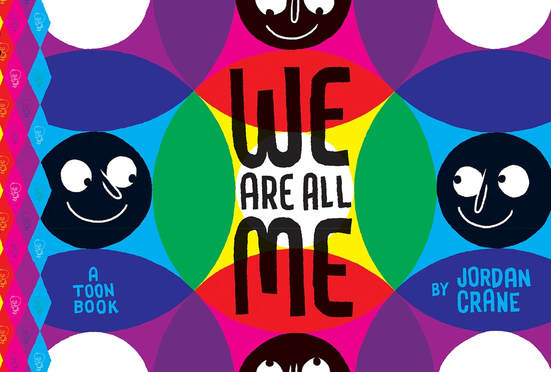

Tempus Fugit Dept.:What follows is a rundown of English-language comics newly published in North America in 2018 that have left strong impressions on me — but it is NOT intended as a "best of 2018" list. Frankly, it's too quirky, too patchy and selective, to qualify as a professional survey of the field's best. It testifies to a comics-reading life hemmed in by other obligations, and by the amount of time I've spent rereading, teaching, and writing about titles from before 2018. For example, this list is manga-less, testifying to the fact that I tend to binge-read manga seasonally, guided by nudges from my daughter Nami Kitsune Hatfield (and those binges usually consist of older titles; my time lag on manga is considerable). Likewise, this list is Eurocomics-free. These are sad omissions, but a fair take on how my year has gone. Also missing are webcomics, as I don't yet have a steady webcomics-reading habit or a firm sense of that huge, and vital, field. That said, I stand by the following list, which contains, IMO, some of the best print comics published in North America this past year. They are not all young readers' comics, i.e., not all books I'd review for this blog — but those I have reviewed on KinderComics are mostly up top. (Doing KinderComics has certainly shifted the balance of my comics-reading toward kids' titles.) Two picture books round out the list, at the bottom. The Prince and the Dressmaker, by Jen Wang (First Second Books). A gorgeously drawn, progressive, Belle Époque fairy tale about couture, gender, desire, hiding out, and coming out. Its nuanced artwork, tender and expressive, is charged with complex, unspoken feeling. I dig both the aesthetic loveliness and generous spirit of this graphic novel, which is positively swoonworthy. KinderComics reviewed this on March 14. The Dragon Slayer: Folktales from Latin America, by Jaime Hernandez (TOON). The first children's book by the great Xaime (see Love & Rockets, below) is a treasure: a set of three stories that have the off-kilter, arbitrary, but oh-so-perfect logic of traditional tales. These are droll and lovely comics, delivered with the author's trademark classicism, clarity, and verve. Just a plain delight. In a better world, folk and fairy tale comics like these would be reaching millions of young readers every month, in affordable comic book form (I dream of a more culturally diverse Fairy Tale Parade for the 21st century). May there be more of this kind of work from Xaime! KinderComics reviewed this on April 5. Be Prepared, by Vera Brosgol (First Second). The author of Anya's Ghost switches gears, from children's Gothic to a Raina-style memoir of summer camp. An ambivalent, though affirming, tale of cultural heritage, tween awkwardness, and hard lessons. Sharp, funny, and refreshingly unsentimental, with killer cartooning and comic timing. I like the fact that Brosgol sometimes lets her kid protagonists be jerks and that she indulges in bodily and occasionally raw humor. KinderComics reviewed this on May 21. The Cardboard Kingdom, by Chad Sell et al. (Knopf/Random House). A paean to creativity and community: a diverse bunch of kids get together, make stuff, and transform their suburban neighborhood into one nonstop live action role-playing campaign: a shared game of let's-pretend, populated with stalwart “heroes” and gleeful “villains.” Remarkably, this novel follows almost twenty distinct characters (each chapter focuses on a different character or group, and each is co-written by Sell and another creator) and yet it all hangs together, building to a big, punchy climax. Along the way, many of the characters defy societal norms — especially around gender and sexuality — and Sell and co. build a utopian vision of community that happily incorporates and celebrates difference. I’ve admired this book from the first, but when I reviewed it back on May 28, I did complain a bit, saying that the story seemed a bit too perfect, too quickly and neatly resolved, and that the book telegraphed its punches too obviously. However, having reread and taught The Cardboard Kingdom this past week, I’ve come to see it as a remarkable achievement, and I expect that it’s going to be a watershed for middle-grade graphic novels. Sell’s cartooning, lively and eminently readable, is the unifying factor, and should not be underrated (he hides his painstaking work in plain sight: everything seems effortless). I don’t think I’ve ever seen a better treatment of what superheroes can mean for young children. (What is the “Gargoyle” chapter, if not the story of a young Batman fan?) On a Sunbeam, by Tillie Walden (First Second). Walden has great artistic courage, and a genius for comics. Like Jillian Tamaki and Eleanor Davis, she shows such skill and daring that she leaves me gobsmacked. Collecting and revising her epic webcomic, this graphic novel could serve as Exhibit A of her dumbfounding excellence. It’s a tale of love and community, exile and rescue. In a boarding school. In space. A first-class genre-masher, it works as both a heartfelt queer romance and a caroming space opera. Walden's graceful, economical art conjures up a fantastical world and a found family of diverse, shaded characters. The work is generous, yet dares you to take it on its own terms. I read this in one breathless, late-night sitting, wow, and reviewed it on October 26. Book of the Year? Sabrina, by Nick Drnaso (Drawn and Quarterly). Not a children’s book. Chill and frightening, but oh so terribly human and believable. Here's what I had to say about this timely and upsetting graphic novel on its initial release: "A tense, quietly devastating clockwork of a book—drenched in unease and punctuated by moments of muted terror. A study of misinformation, fake news, post-9/11 paranoia, and epistemological doubt—and, more importantly, how it feels to live with these things, on an everyday human level. Sterile, clip-art like drawings, deadpan, seemingly emotionless, and inscrutable, become, as you read in deeper, perfect conveyors of dread." I stand by that: reading this book was an unsettling experience that stayed in my head, haunting me, nagging me, for days. Why Art?, by Eleanor Davis (Fantagraphics). A satirical allegory of sorts, smart and stinging as a whip, but humane and thrilling too. It starts by poking fun at the fatuous self-regard of artists, but then upshifts into a poignant, confounding fable about how much (too much?) we demand of art in catastrophic times. Davis is one of the best comics artists today, an impeccable cartoonist and designer, also a great writer. Again and again, she turns mockery into sympathy, unsettles settled opinions, and overturns smug knowingness in favor of a more complex, and earned, humanity. Small book, big yield. I reviewed this at Extra Inks (the Inks and Comics Studies Society blog) on March 24. Girl Town, by Carolyn Nowak (Top Shelf). I discovered Nowak through her erotic minicomic, No Better Words (which is great — see my mini-review here). Soon after, Top Shelf released this, her first big collection, which includes the celebrated story "Diana's Electric Tongue" and other tales. Aptly named, Girl Town is a queer-positive anthology of young woman-centered tales that evoke uncertain, often unspoken feelings (it could be considered Young Adult fiction, though I don’t think it’s YA by design). The stories are perhaps uneven, some more finished-seeming than others, but every one of them hits home. The best of them are great. Nowak does tenderness and feeling so well; you can feel the desire welling up in her characters. Her cartooning and timing: flawless. I bet we’ll be raving about Carolyn Novak years from now. Flocks, by L. Nichols (Secret Acres). This memoir about growing up queer in a fundamentalist community depicts its protagonist as a rag doll, surrounded by characters rendered in more conventional fashion. At the same time, the pages are full of scientific notation, as if guilt, fear, and alienation could be drawn out as a physics problem — aesthetically, I’ve never seen another comic like it. Flocks does that thing that I long for comics to do: communicate feeling through a complex visual language of its own. Remarkably, this story about how to find your identity within and between your “flocks” (your communities, or social worlds) avoids rancor in favor of a comprehensive love and understanding, even as it criticizes and ultimately rejects fundamentalism and its protagonist literally transitions into a new life. A beautiful, affirming book, deeply personal, and a compelling addition to the growing comics literature on trans experience. I wrote about this briefly on KinderComics, on October 9. From Lone Mountain, by John Porcellino (Drawn and Quarterly). John P is a national treasure. From Lone Mountain is an exquisite collection of four to five years’ (seven issues’) worth of comics and stories from his indispensable zine King-Cat. Tender, heartbreaking remembrances of everyday life and of life-changing loss and struggle, all distilled down into John P’s crystalline, oh-so-spare, Zen-minimalist style. A record of a hard passage in the life of one of America’s greatest cartoonists — and that rare thing, a truly moving comic that brings tears to my eyes. I reviewed this wonderful book for The Comics Journal, back in March. Poochytown, by Jim Woodring (Fantagraphics). Woodring returns to the Surreal, dreamlike world of Frank (bucktoothed zoomorph of uncertain species) to rewrite, or unwrite, an earlier episode. It's as if the jury has been instructed to disregard earlier testimony (but who can ever forget such testimony?). The result feels like having a recurrent dream with variations, or like winding back to the start of something that seems oddly familiar but then fails to stick to what you expected. No matter: the wordless misadventures (joys, sufferings, weird trips) of Frank and company are among the most hypnotic comics I know, and also the most alarming, as the characters' surface cuteness often gives way to amoral selfishness, self-defeating foolishness, and even downright cruelty (these are adult books). Behind the mask of cuteness lies a loving terror at the mysteries of life. This graphic novel is an especially loaded example. In short, Poochytown (rendered as ever in the mesmerizing Woodring Wavy Line) is strange and delightful. Whenever I finish a Woodring book, I feel as if I've come back from a journey to a distinct and unnerving place — one I always want to revisit. In addition to the above self-contained graphic books, I have, of course, continued following a number of comic book (i.e. pamphlet or floppy) serials this year. Most, but not all, have been direct-market series in the traditional sense. Here are the four that have impressed me most. None began this year, and so none is quite new, but of all the floppies I've tracked, these have been the most meaningful for me: Tongues #2, by Anders Nilsen (No Miracles Press). It might not be quite right to call this a "floppy" serial, but it is literally that, i.e. a saddle-stitched comic book periodical (or sporadical). Really, it's as lavish as any of the books listed above: a real art object. It's also narratively dense and, frankly, mind-boggling. At once a fable, myth fantasy, puzzle, and brutal take on our brutal world, Tongues consists of multiple intertwining stories that promise some kind of awful shared meaning. Nilsen uses the fantastic to probe and trouble, never to back away from what's hard. I have no idea where this is going, but each new issue startles and then haunts me. And its beautiful, oversized format is narratively meaningful: not just sumptuous, not just lavishly drawn and printed, but insinuating, teasingly coded, designed down to the last significant detail. These are masterful comics, eerie and destabilizing in the best way. (I reviewed the first issue of Tongues for Extra Inks on August 1.) Frontier #17, by Lauren Weinstein (Youth in Decline). Like Tongues, Frontier might be considered a kind of "art floppy," one that few comic book stores will carry. That's too bad, because this quarterly anthology is outstanding. It devotes each issue to a single artist, and there have been some wonderful ones: Jillian Tamaki, Eleanor Davis, Rebecca Sugar, Emily Carroll, Michael DeForge, and more. Honestly, every issue is strong. This issue, by Lauren Weinstein, consists of "Mother's Walk," a memoir of childbearing and parenting, in fact the story of her second child’s birth. Gutsy, explicit, tender, alarming, and funny, it’s a wonderfully frank comic about a dimension of life too often soft-pedaled, sentimentalized, and mystified. Weinstein paints and cartoons in a way that's deliriously free and unconventional. As soon as I read this book, I decided to add it to the reading list in my comics class next semester. Weinstein says she has more stories to tell in this vein — a whole book, even — and, wow, I would queue up for that. She is great. I wrote about this briefly on KinderComics, on October 9. Love & Rockets #4, 5, and 6, by Gilbert Hernandez and Jaime Hernandez (Fantagraphics). I love no comic book series more than this one. Launched in 1981, L&R has lasted long enough to come to terms with its own history, and recent stories by Gilbert and Jaime have done that, with lived-in characterizations, loving revisitations, reflections on growth and change, and, most importantly, fresh, disconcerting, surprises. Just when I think I’ve got them pegged — just when I’m getting all nostalgic about their work — they throw another curve ball, and I get a little shock, a mild sense of disorientation. And I love it. Funny, poignant, masterfully drawn comics, always a pleasure. This year’s issues have been particularly great, confirming yet again that Los Bros are two of the best cartoonists alive. Sex Criminals, by Matt Fraction and Chip Zdarsky (Image Comics). This risk-taking genre mashup, a ribald, at-times explicit tale of desire, shame, romance, and crime, no longer quite works as a traditional comic book serial: long wait times have attenuated its suspense, and these days each new issue requires me to reread the previous ones just to stay more or less unconfused. (I’ve had that same experience with L&R.) Sex Criminals is an odd duck, pushing at the seams of several genres at once, and sometimes it falters. Further, its queasy comedy may sometimes seem glib. But I think it's terrific; from my POV, Fraction has far outgrown glibness. Further, I delight at Fraction and Zdarksy’s self-questioning way of complicating, perhaps even sabotaging, their initial premises. Gutsy, weird stuff. So, I look forward to reading this series to its end. And, on the more obviously commercial, work-for-hire side of serial comics, there's the final arc of Mister Miracle, by Tom King and Mitch Gerads (DC Comics). By rights I should hate this, but I don't. A dark, depressive update on Jack Kirby's beloved Fourth World character — the super escape artist, emblem of freedom and possibility — this story begins with the hero trying to kill himself, and goes downhill from there. But then uphill, maybe? The final movement, and last couple of issues, are enigmatic but guardedly affirming. Overall, though, this series is harsh, troubling. King, the direct market's laureate of depression and trauma, works in an Alan Moore-ish vein, with a similar clinical formalism that offsets the bruising emotional content. At times ultraviolent, at other times perversely comic, this is one revisionist superhero comic that actually seems to be trying to say something. I can't say I love it, but it has a mind, and some genuine ache, behind it. Increasingly, I find myself rejecting nostalgically literal takes on Kirby, and this came as a sort of tonic relief from that mode — something oddly personal. So, yeah. Finally, I also want to mention two picture books from 2018 that do not seem to be "comics" in the usual sense but happen to be by established comics artists and are wonderful visual poems: They Say Blue, by Jillian Tamaki (Abrams). A young girl looks at the world around her in light of what people conventionally “say” about it — and her thoughts deliver up the world anew, richer and more beautiful than convention will allow. The landscape, the weather, the water, the sky, and small observations about everything: They Say Blue builds out from these, in lyric rather than narrative form. The book steers into Romantic conceptions of the Child as naively wise and gifted with unblinkered sight — yet at the same time Tamaki thankfully includes notes of mundane business and everyday frustration, touches that ground the book’s sense of wonder. Very much an observational picture book in the modernist here-and-now tradition — Tamaki does not regard it as a comic — They Say Blue is visual poetry of a high order, and a drop-dead gorgeous book. Is there anything this supremely gifted artist cannot do? KinderComics reviewed this on April 26. We Are All Me, by Jordan Crane (First Second). Lately I've been teaching this picture book in English 392, and Crane recently came to my campus to talk with my class and other visiting students. This too is a lyrical picture book rather than a storybook, and in fact it is even less "narrative" than They Say Blue. Built around the concept of interdependence, We Are All Me is a brief but very rich poetic evocation of the web of life. It balances figural and abstract forms and creates its own system of colors and color-transitions, taking us from the individual human figure to the cycle of life and then into the atomic, even the quantum, level. As it moves toward the infinitesimal, it embraces the infinite. Finally, it brings us back to the human form, the individual "me," yet also the affirming collective "we." This is not a very original conceit -- indeed, the book builds upon a familiar, almost proverbial, wisdom -- but Crane realizes it with beautiful, glowing pages and a suite of braided and nested forms and inspired visual rhymes. The total effect is transporting. I have never seen a mass-market book with such fluorescent, eye-boggling color. Quite lovely: a book to get drunk on.  The above are the graphic books that have meant the most to me in 2018. They have stood out in mind and stayed with me, and in many cases moved me. I’ve read and re-read them, stared at and savored and wondered over them. In my opinion, it's been a great year for comics in the US, and there's lots more to love beyond these few titles. Man, do I have a lot of catching up to do as a reader! For example, there are new titles or new US translations by Emily Carroll, Junji Ito, Nagata Kabi, Hartley Lin, Héctor Oesterheld & Alberto Breccia, Katie O'Neill, Keiler Roberts, and others that I want to experience. Plus, there's a number of ongoing floppy-to-trade serials I am seriously behind on, such as Monstress, Saga, and Paper Girls, and there are promising new floppy series to track (The Seeds and Bitter Root, among others). In fact, there's a ton of promising new work out there! (And what about the comics I don't yet know anything about, the genuine surprises? Maybe this week's CALA festival will once again introduce me to a few. So much to learn!) And, no, I haven't yet finished Jason Lutes's collected Berlin. I'm saving it. :) PS. I have to say, First Second Books is my Publisher of the Year. They have put out such strong books in 2018 (including ones by Sarah Varon, Graham Annable, and Aaron Renier that very nearly made the above list). Theirs is one amazing catalog. Twelve years and counting, they've been bringing great comics into the world, but 2018 in particular has been a superb year for them.

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed