|

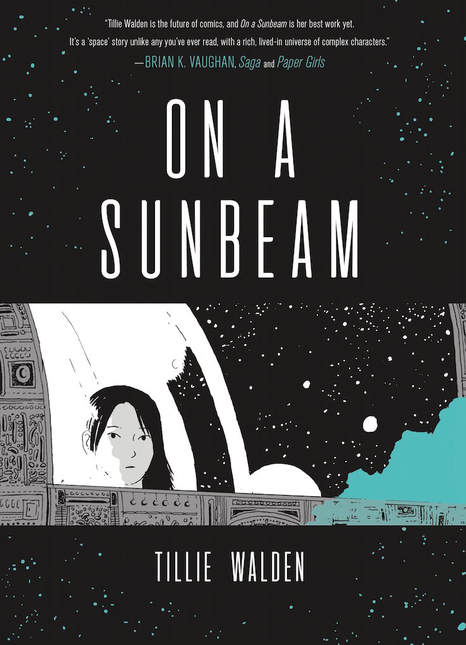

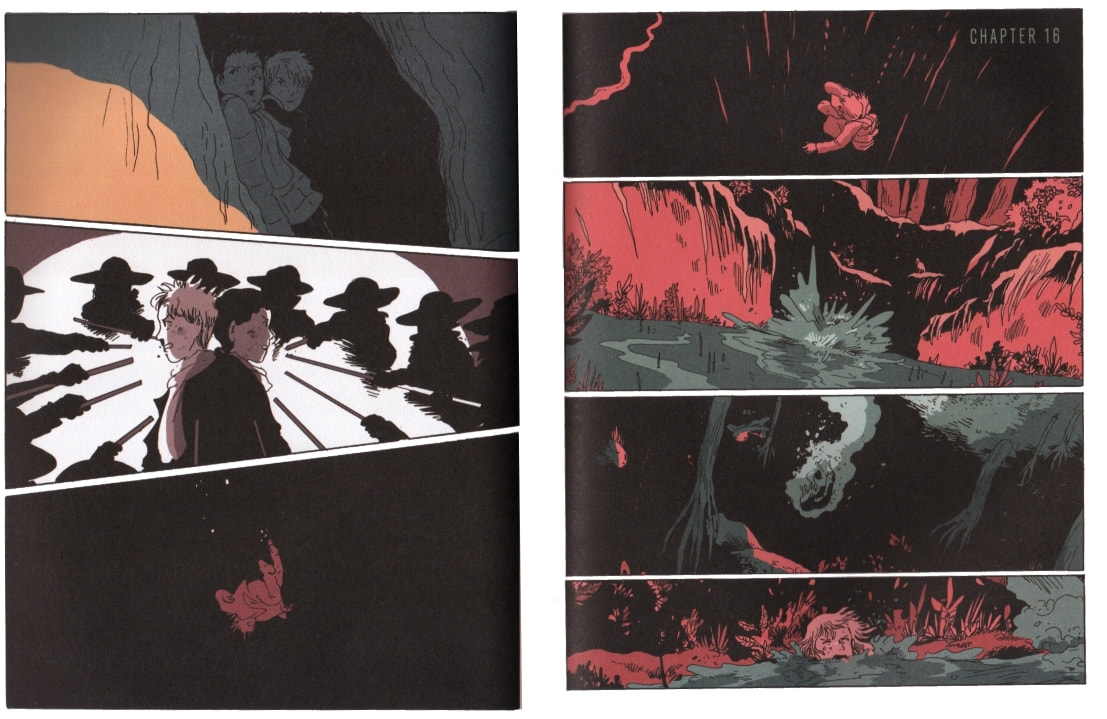

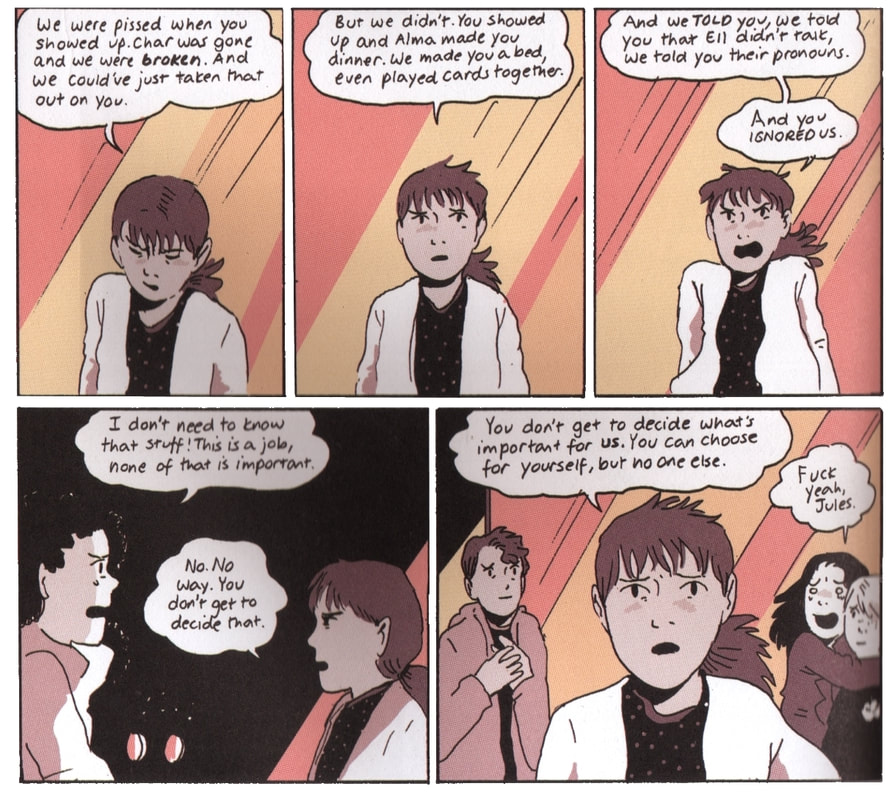

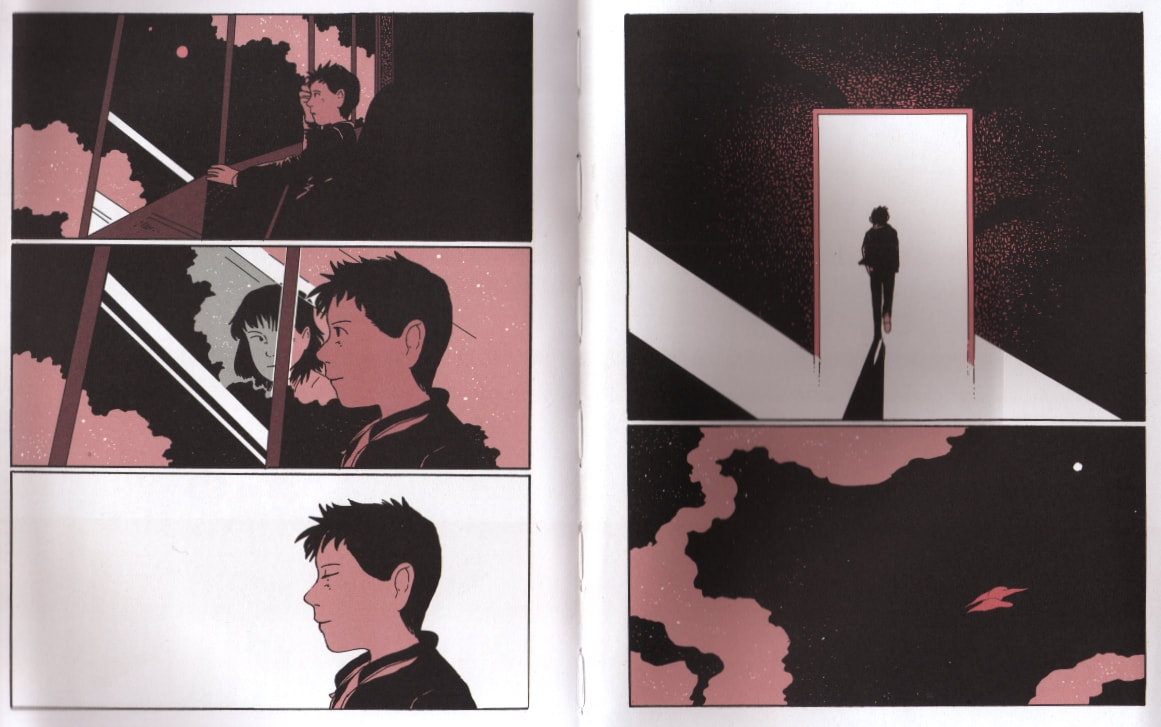

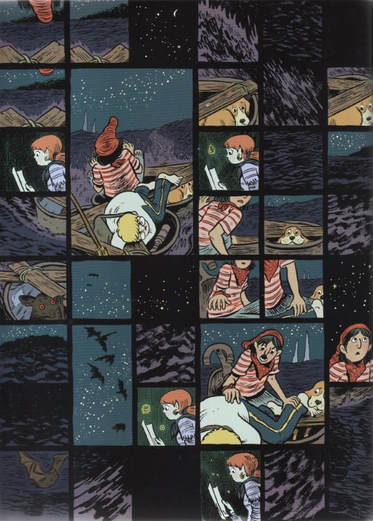

On a Sunbeam. By Tillie Walden. First Second, 2018. ISBN 978-1250178138. 544 pages, softcover, $21.99. Tillie Walden has an uncanny gift for, and dedication to, comics. Her newest book On a Sunbeam (compiling and adapting her 2016-2017 webcomic of the same name) is a gift in itself: a queer romance that starts as a young adult school story—an acute exploration of tenderness, social anxiety, and the keeping of secrets—but then blossoms into a breathless adventure tale. At the same time, it's a paean to queer community and found family, while also being, wow, a space opera. I'm not kidding. In other words, On a Sunbeam is a miracle of genre-splicing and of unchecked, visionary cartooning—one in which Walden does whatever she wants, while yet upholding a traditional, eminently readable form. As soon as I got a copy, I was pulled along, pretty much helpless, for an ecstatic 540-page ride. The story ought not to work, in theory. On a Sunbeam is galaxy-spanning science fantasy in an undated future, one governed less by grounded scientific extrapolation, more by poetic metaphor. The spaceships resemble fishes, swishing across the skies and through the cosmos on fins. Buildings float through space looking exactly like earthbound buildings: a church, say, or a schoolhouse. This is deliberate; Walden treats space like terrestrial geography, only bigger. Ditto architecture. Much of the action involves the repair of damaged or derelict buildings out in space, by a "reconstruction" team whose job falls somewhere between renovation and archaeology. They deal in statuary, stone, and tile as well as high tech. Often the settings don't feel like "space" at all—until they do. No one wears spacesuits, though everyone's bodies must somehow adjust to being in deep space. Oh, and the cast seems to consist solely of women and genderqueer characters. What sort of universe is this? To hell with what would work "in theory." The story, for its first 2/3 or so, shuttles back and forth between two main settings: an upper-crust boarding school (in space), and the Aktis (or Sunbeam), the reconstruction team's spaceship. But it also shuttles back in forth in time, across a gap of years: the "school story" part of the plot happens in flashback, five years past, while the story's "present" follows Mia, formerly of the boarding school, now a (green) member of the Aktis crew. Walden skillfully uses layout and coloring variations to set these two timelines apart (and ultimately to bring them together). What really ties these timelines together is the bond between Mia and her schoolmate Grace, a socially withdrawn girl of unknown origins. Grace and Mia share a romance that is tender and profound: a genuine love story. However, their bond breaks when Grace is mysteriously summoned home from school. Her home is an enigma. Mia longs to see Grace again, but the years go by and a reunion seems impossible. About midway through the book, though, Mia and her Aktis family undertake a fantastical quest for Grace's homeworld, tying the book's several plotlines together. The final third brings the Aktis (and us) to an otherworldly setting worthy of Jack Vance or Keiko Takemiya. On a Sunbeam has tremendous emotional and tonal range. The anxious school scenes of the first half capture budding relationships, first steps toward intimacy, and uneasy social maneuvering, resonating with Walden's great memoir Spinning. The bonding of Mia and Grace recalls, for me, the lyrical evocation of young and growing love in the book that introduced me to Walden, the dreamlike I Love This Part. Walden is great at conjuring the rivalries and vulnerabilities of young women in social groups, the tension between ringleaders and outliers, and the no-bullshit demeanor of girls among girls, at once strong and fragile. On a Sunbeam carefully builds the relationship of Mia and Grace, two believably different young women, into a deep, unqualified love; their unspoken understandings and gestures of mutual care and self-sacrifice make them a couple to root for (and the book, delightfully, suggests that queer romance is common in their school and world). Yet Mia's later initiation into the Aktis crew creates other deep relationships, both among the crew and between Mia and every other member. The tenderness of the Grace/Mia dyad suffuses everything that comes after, and what begins as a rough, contentious team gradually becomes, emphatically, a family, one of Mia's own choosing yet defined by complex bonds with and without her. The book's range broadens dramatically in its final third, as the plot upshifts with a vengeance: Walden leaps headlong into phantasmagorical SF, but also abrupt, jolting violence, frenzied cross-cutting, and nail-gnawing suspense. This is the very stuff of pulp adventure, yet made more urgent by a reservoir of earned emotion. Lives are risked, a world uncovered, and secrets revealed (my favorite being the backstory of Ell, the ship's non-binary mechanical whiz). I could hardly hold on to my chair during the last hundred pages! Yet mostly On a Sunbeam is a story about love. The word that keeps coming back to me is tenderness, and Walden hits the tender spots again and again, not with cynical knowingness but with the thrilled self-discovery of an explorer who has just realized what her explorations are about. Relationships deepen, and at some point we realize—that is, Walden shows us—that On a Sunbeam is not simply the story of a single idealized love but of loving community, and of what it means to take others as they are. It's a story about unlike people forging bonds of mutual respect and care. Among the many exciting climaxes in the book, the most important ones, to me, are embraces. On a Sunbeam wears its heart on its sleeve. All this is delivered with the utmost grace, with a style whose delicacy reminds me of C.F. (Powr Mastrs) and whose out-of-this-world gorgeousness calls to mind Takemiya and Moto Hagio, those masters of shojo manga SF. Remarkably, Walden's style hardly ever betrays signs of underdrawing; the characters and panels seem to have found their perfect form without hesitation. Her style might be considered a variation on the Clear Line—clean contours, no hatching, and the use of contrasting solid blocks of color to solidify form—but without the cool meticulousness and literal, mimetic colors that such a comparison would imply. She's freer, and her light, unfussy lines are elegance itself. This is the more remarkable because her characters, emotionally, are all about undercurrents and anxiety; Walden renders their struggles with an unerring economy even as they're going through hell. Open white space, blocks of color and of darkness, the selective paring of background details—all these artistic strategies bring the story into crystalline focus. The spareness and cleanness of Walden's pages belie, or rather render all the more piercingly, the struggles going on among and within her characters: In my comics classes, I like to say that every book of comics teaches you how to read it, becoming its own instruction manual. That is, no generalized understanding of "comics" as a whole is going to make every new comic you encounter easy to understand, because comics aren't as formally stable and consistent as that. Instead, the form shifts, or artists shift it, toward new strategies and purposes—but attentive readers will learn how to read in a comic's particular way. I think about this when I see pages like the above, or On a Sunbeam's climactic pages: Coming at these pages unprepared, sans context, I would hardly know how to read them. But it's a testament to Walden's skill, and the gripping human story she tells, that these spare pages speak volumes to me now. On a Sunbeam is full of payoffs like this; it's masterful. It's also moving and exhilarating. As I said, uncanny. PS. I was sorry to miss Walden's conversation with Jen Wang at L.A.'s Chevalier's Books on Oct. 8. But I look forward to her signing and exhibition at Alhambra's Nucleus gallery on Feb. 22. First Second Books provided a review copy of this book. (Note: It was particularly challenging to scan pages from On a Sunbeam, a roughly 6 x 1.5 x 8.5 inch brick!)

0 Comments

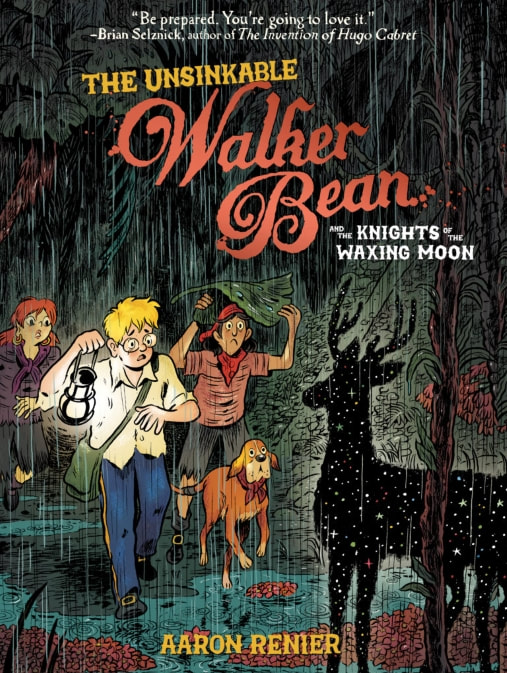

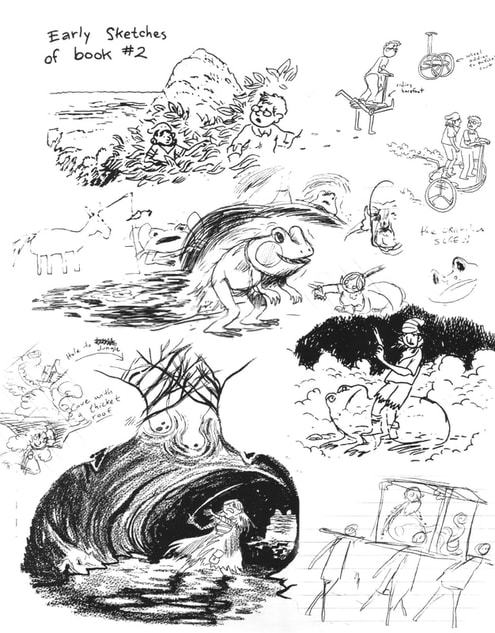

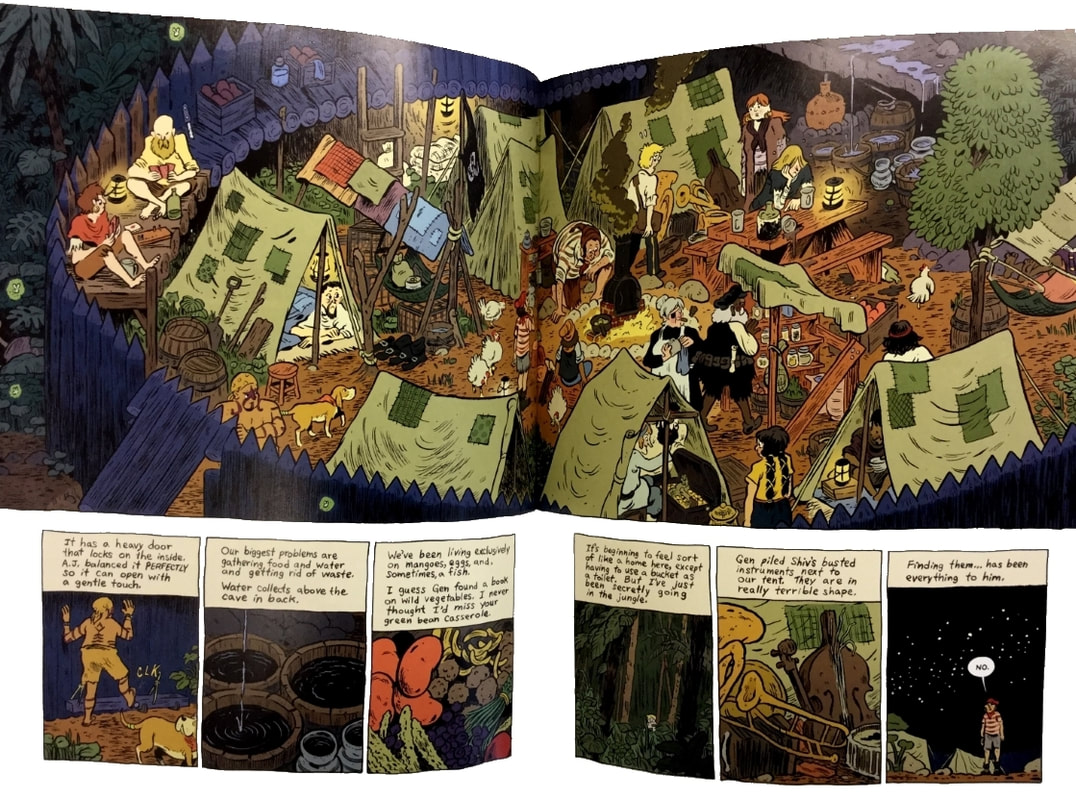

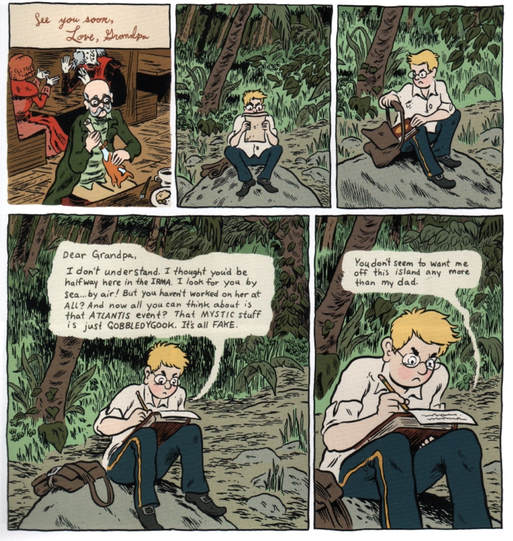

The Unsinkable Walker Bean and the Knights of the Waxing Moon. By Aaron Renier. First Second, 2018. ISBN 978-1596435056. 288 pages, softcover, $18.99. Colored by Alec Longstreth. Eight years ago—my gosh, eight years ago—author-artist Aaron Renier and colorist Alec Longstreth gave us The Unsinkable Walker Bean, a gobsmacking pirate yarn and reckless feat of cartooning. It was, is, absurd and terrific, overfull and bursting with notions. Far-fetched and outrageous, rigged to the point of obsessiveness, it’s also generous and heartfelt, and a gushing testimony to Renier’s love of world-building. Reviewing it was a thrill. Now Renier and Longstreth are, yes, back with a second Walker Bean book that I can only describe as more of the same, but longer and even more ambitious: The Unsinkable Walker Bean and the Knights of the Waxing Moon, an adventure at once hectic and transporting, overbusy yet oddly soulful. When I first read it, it drove me a bit nuts, so mazy and bewildering is its plot. When I re-read it, though—well, I think I got it. The world of Walker Bean consists of salty pirate tales (in the Stevenson tradition) blended with high fantasy. It takes place in an odd variation on the known world that mixes real and invented geography, in an unspecified period that feels like a dreamlike rewriting of the nineteenth century. Walker is a shy, bookish boy, frankly a nerd: brilliant, but fragile and sensitive. People treat him as a softy, but he has steel in him; on the other hand, he can be a bit of a pill. Most unwillingly, Walker gets pressed into nautical adventures that carry him far from his home on Winooski Bay and introduce him to supernatural forces and secret histories. The first book concerned a magical skull, two monstrous “sea-witches,” and a seafaring quest, much of it aboard a tricked-out ship called the Jacklight, which could travel over land as well as wave. In that one, Walker was joined in his travels by Shiv, a powder monkey, and Genoa, an intense and mysterious adventuress. They are still together in the new book, and make for a sturdy triad (in a sort of Harry-Ron-Hermione way). Knights of the Waxing Moon shares the spirit of its predecessor, and offers continued treasure-hunting, with many of the same characters (as well as many new ones). But there’s less sailing, now, because the story takes place mainly on the same haunted archipelago where Walker and friends were stranded at the end of the first book: the Mango Islands. Basically, this is a “mysterious island” tale. Something happened on the archipelago long ago, something that still casts a long shadow. Competing treasure-hunters, some much older than they appear, seek a source of power—a magical metal—and again supernatural agents and occult histories are high in the mix. Mistaken identities play a part, as do bemusing visits to the past. Mysterious shadow-beasts that guard the islands add a whiff of Miyazaki: the environment seems neither benign nor malevolent, but sublime and indifferent. As in the first book, the stakes are high, the violence consequential, and the scares properly scary; Walker and friends experience sadness, anxiety, and loss along with ripsnorting adventure. If I faulted the first Walker Bean for getting lost in its unlikely, careening plot, I have to say the same of the second. Plot-wise, Knights is the equivalent of juggling cutlasses and cannonballs—tricky, that is. I confess that on first reading I had trouble following the story’s logic, its links and reversals, its mad, ambitious sprawl and ballooning cast of characters. In fact, I finished my first reading—a breathless, late-night binge—in a knot of frustration. For a moment, I thought of the book as a failure: a dream that had gotten hopelessly blurred en route. Hallucinatory flashbacks, inscrutable clues, magical MacGuffins, and sudden, disorienting setpieces, not to mention the many new characters, make Knights a challenging, even frustrating tangle. Transitions are often abrupt, and essential details and connections are sometimes left for the reader to intuit. The relationships among the characters are not easy to chart: motivations are shaded, and alliances form or fail on the spur of the moment. Doppelgangers and ghosts abound. Our three young heroes are called upon to change, and Genoa in particular goes through a startling self-discovery. So, there’s a lot to take in. A lot. So confounded was I by my first reading that, in defiance of my schedule and good sense, I reread the book immediately—and reread the first book too. The second time around, Knights seemed to click: I grasped a number of hints and foreshadowings, better understood certain transitions, and, in sum, could more easily negotiate the plot-rigging. If on the first pass Knights seemed jumbled, with a hiccoughing rhythm and befuddling climax, on second read the book revealed an insinuating story with elaborately braided details, a designing shape, and knowing callbacks to its predecessor. As a self-standing graphic novel, Knights may seem overdense, or over-egged, but as one leg in a longer journey, a further unveiling of a big, big world, it’s a marvel.  Although Knights spins its own distinctive yarn, it does require readers to know the first book intimately (not for nothing did First Second reprint the first a few weeks ago). It refers back to its forerunner constantly, in ways both obvious and subliminal—and this was part of my problem on first reading, because I needed the first book in front of me in order to follow the second. Some of these callbacks fulfill mysteries teased out in the first book, while others deepen the mystery, or extend the original’s meaning. Knights, in short, asks to be read alongside its predecessor. At the same time, it outdoes the first book for scale and strangeness: for one thing, it’s about a hundred pages longer. Even then, it seems more compressed, with (often) denser layouts and too-small balloon text. Still, it’s an organic outgrowth of the first book. Revisiting the first, I notice that its back matter includes teasing “sketches of book #2,” and sure enough I do see elements that made it into Knights: Renier clearly had some of this second book in mind more than eight years ago. Knights, then, is both a close sequel and yet its own strange animal. The trickiness of the book’s plot may prove a trial for readers. Yet I take some delight in the way Renier refuses to talk down to us. Clearly, he digs a nested, baroque plot. In fact, his approach to story recaps, on a larger scale, the complicated maps, diagrams, and inventions that he so lovingly draws into the book. I like that. Still, I’d say that the plot is too compacted, and its logic a bit too implicit; this 280-page yarn packs in 500 pages’ worth of complication. At times Knights surrenders clarity for momentum, and, like the first book, sprints through transitions and critical moments that rather beg for a long double-take. What’s more, certain details are left dangling--bait for the next sequel, presumably, but maddening. For example, one of the book’s narrators, a crucial source of exposition, is left shadowed and unidentified, and Walker’s unscrupulous father, briefly glimpsed, remains a nagging loose thread. (I dearly hope it won’t take another eight years to tie off that thread.) More than anything, a passion for worldmaking through drawing animates the Walker Bean books, and on that score Knights of the Waxing Moon matches its forerunner. It piles up, graphically, vividly, a surplus of environments and space, creatures and ships, devices and talismans, all rendered with breathless excitement. Renier, as he zooms ahead, leaves behind a trail of small delights: details that pop out upon rereading, to be savored or puzzled over. In fact the galloping momentum of the story and the luxurious world-building are at odds, making the book at once a sprint and a sightseeing tour, a plot-driven adventure and a dungeon master’s guide (oh man, Walker Bean is a role-playing game just waiting to happen). Judged by the standards of tight, Tintin-esque adventure, the book is a failure—it packs in too much stuff to attain that kind of crystalline form—but as a celebration of drawing worlds into being, man, it’s something. Renier and Longstreth once again turn out beautiful pages and spreads, with a loose, feeling line and sumptuous palette; at the same time, Renier tries out new things in layout, pacing, juxtaposition, and braiding. A labor of love, I cannot help but think. Love and feeling are big for Renier. Both Walker Bean books brim with emotion: characters weep, fret, and startle—gulping, gasping, reacting. They sometimes panic. They get on each others’ nerves too, reproving and arguing with one another. They worry for each other. Walker and his cohort, and even the heavies, wear their emotions near the surface, and many scenes are raw with feeling. Even the quietnesses can be supercharged. Take for instance this loaded moment from early on, as Walker, feeling abandoned, starts an angry letter to his beloved Grandpa, but then thinks better of it: Scenes like these show that Renier values not only the pleasures of drawing but also the vital emotive connection between characters and reader. Some of the relationships in Knights are tumultuous—in fact, testing or reaffirming friendship in the face of severe trials is a large part of what the book is about. The sheer feelingness of Walker Bean is a necessary balance to the baroque plotting and ecstatic drawing. Renier cares about his adventurers, and faithful readers will too. Structure-wise, Renier may be aiming for the kind of unfolding epic that Jeff Smith crafted in Bone. Feels like it. But he isn’t working within the same serial format, one that allowed Smith an unhurried pace, a gradual unspooling and deepening of his imagined world. Nor is Renier publishing with the same momentum as, say, Kazu Kibuishi, whose Amulet series has yielded eight roughly 200-page volumes in a decade. The Walker Bean books are different: jam-packed, overstuffed, sort of obsessive. They bespeak, again, a love of drawing and knotty, puzzle-like storytelling. Renier, I think, loves world-building in a way that can barely be corralled into sensible, well-structured volumes (though he does strive mightily after an overarching structure). His penchant for overstuffing recalls, for me, Mark Siegel et al.’s elaborate 5 Worlds series, except it’s less mediated, more personal: not the result of a carefully managed collaboration that subsumes individual quirks, but the result of one artist running wild. And, you know, I kind of love him for that. Readers who loved the sheer outrageous overspill of the first Walker Bean will also dig the second. Me, I’ll reread these books and take pleasure in them, again and again. In this age of well-shaped, well-behaved, and precisely marketed graphic novels for children, Walker Bean is exceptionally weird, hence wonderful. My gosh, I hope for a third volume. And more.... First Second Books provided a review copy of this book.

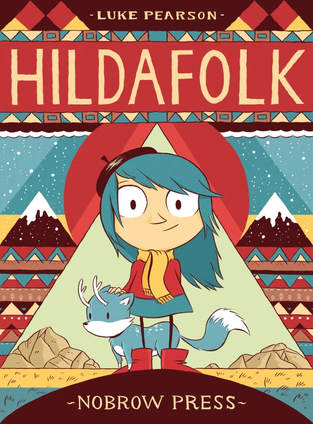

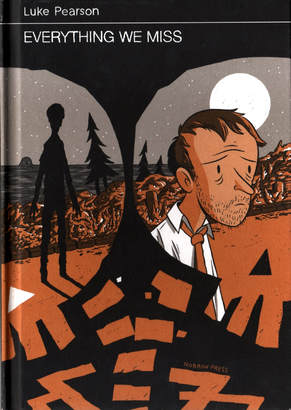

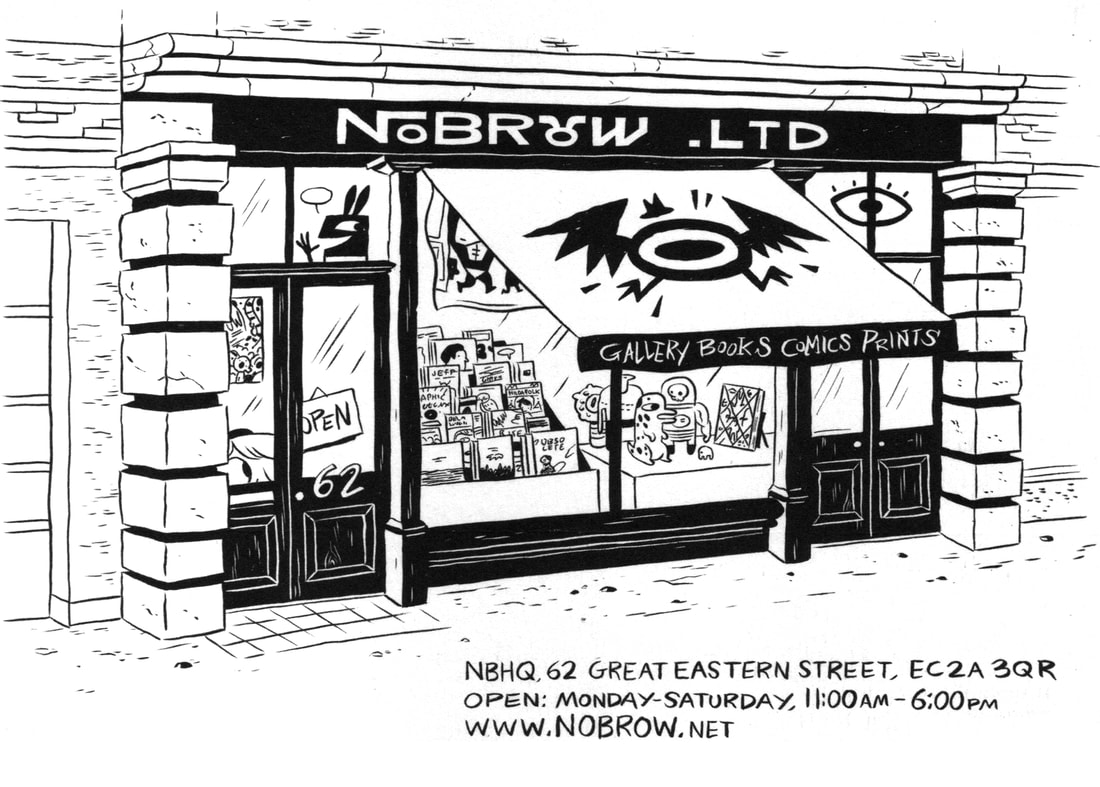

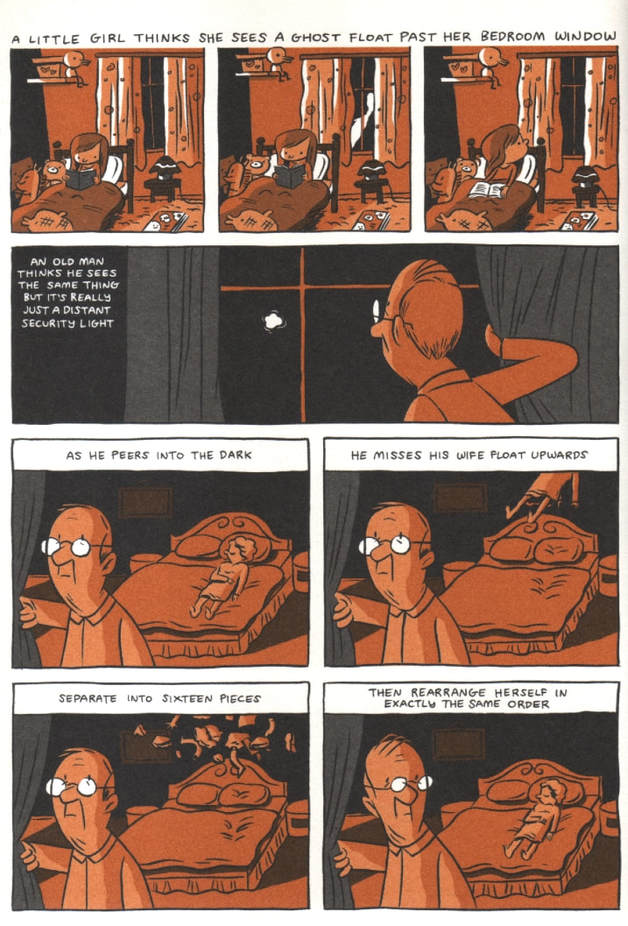

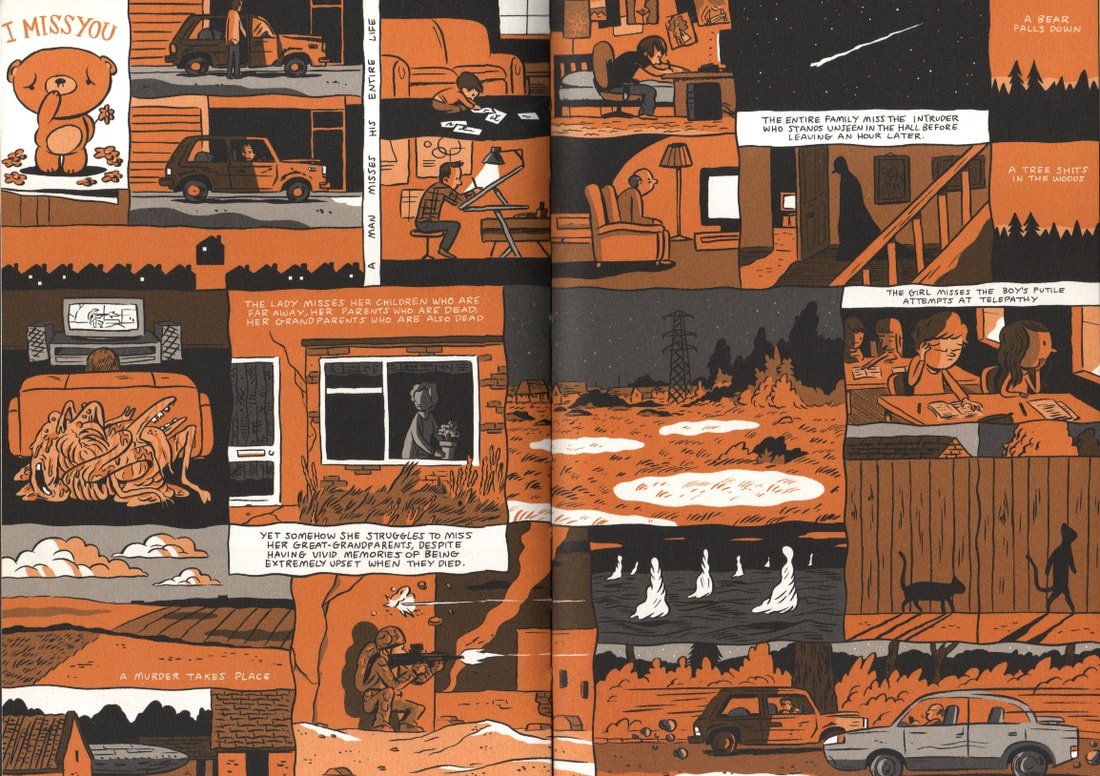

Being a series on one of my favorite cartoonists I first encountered cartoonist Luke Pearson’s work about eight years ago, in a curious, frankly mismatched pair of books, both put out by the London-based boutique publisher Nobrow. The first of these was Hildafolk (2010), a charming 20-page vignette in the form of a full-color, saddle-stitched pamphlet. Hildafolk was part of Nobrow’s 17x23 series (so named for its dimensions, in centimeters)—think of it as a sort of exalted floppy. A child’s adventure, it ended oh so quickly, but suggested a world of further adventures lying in wait. Little did I know: this was the project that would turn out to be the hub of Pearson’s career, to date. The second book, Everything We Miss (2011), was emphatically something else: a melancholy visual poem about loss, loneliness, and our capacity for blind self-absorption, in the form of an even smaller (15.5 x 22 cm) hardcover of 40 pages. I rediscovered Everything We Miss on my shelves the other day: a compact book in an odd palette of black, grey, and two vivid shades of orange. It’s quite sad, and very much an alternative comic for adults. Both books are beautiful—and it was the combination of the two, rather than either of the books on its own, that clued me in to Pearson's talent. I owe my encounter with these books to a family sojourn in London in summer 2011, and particularly to the splendid comic shop Gosh! (then still in its Bloomsbury location, opposite the British Museum, as opposed to its current space in Soho). These are the books that introduced me to Nobrow—these, and then Ben Newman’s Ouroboros (another 17x23 pamphlet), and then Jon McNaught’s two small, gorgeous hardcovers, Birchfield Close and Pebble Island. As I recall, it was Pearson’s work in particular that inspired me to seek out the Nobrow shop (then located on Great Eastern Street in Shoreditch), a visit I recall fondly. I’ve been fairly smitten with the Nobrow brand since. Of the two Pearson comics I discovered in 2011, Hildafolk struck me as the more delightful, while Everything We Miss seemed the more determinedly “serious.” When first I read Everything We Miss, I thought of Chris Ware, not for drawing style so much as a strange combo of formal knowingness—that is, a kind of designing aloofness—and terrible poignancy. In part, Everything We Miss is about watching people suffer. But on re-reading, I think less of voyeuristically peeking into people’s suffering, and more of the poignancy. Also, the style, I now think, bespeaks Seth or Kevin Huizenga more than Ware, with something of Huizenga’s penchant for quiet unease and perhaps sadness, but also wonder—all this, again, allied to an ingenious formalism. Re-reading the book, I also recognized a vein of sly humor, via Pearson's low-key sifting-in of bizarre details. Essentially, Everything We Miss depicts the sad, crumbling end of a couple’s relationship, but also their inability to see other people’s lives—and a host of peculiar, startling things—going on around them. Trees dance; bodies break apart and reassemble; asteroids nearly strike the earth. The estranged lovers do not notice. Their obliviousness stands in for human obliviousness in general, as the book's roving eye makes plain: Meanwhile, braided visual metaphors lend heft and quirkiness to an otherwise despondent story: Shadow-shapes filter in and out of people’s bodies, grabbing at their mouths, their brains. Odd, semi-crustacean creatures observe human doings from the neglected corners of our everyday spaces, always slipping just out of sight. A two-headed skeleton (reminding me of Ware’s “Quimbies the Mouse”) graces the first page and the last (and, implicitly, the cover). Is this a metaphor for the couple's dying relationship, as opposed to either of the two individuals who made up that relationship? And/or for the miraculous, sometimes grotesque details of the world that continually escape us? The book closes ambiguously, with a near-suicide that ends in continued living—though whether this is a matter of life clinging to life, or life hanging on desperately to something that’s already dead, is hard to say. The willed darkness of the story seems indebted to other alt-comix, though Everything We Miss has its own muted shocks, and own loveliness. The book seems to turn on a pun that conflates "missing" in the nostalgic sense (that is, pining away: I miss you) with "missing out" in the sense of failing to notice, or failing to take part in, the world. The climactic spread points out this double meaning with a mix of details both sublime and trivial, and in a tone that's hard to peg, at once melancholy and whimsical: A bear falls down / A tree shits in the woods. Self-reflexively, the spread seems to point to Pearson's own cartooning as a habit that may cause him to miss "his entire life" (a common concern among cartoonists: see Pearson's Ware- and Huizenga-like map of his working environment, from Solipsistic Pop #4, 2011). Meanwhile, ghosts and marvels abound, quiet places reserve dark secrets, and half-glimpsed mysteries impinge on mundane life: A panel about a lady missing her family borders both a panel of, apparently, warfare, and another panel of someone perhaps watching the same warfare on TV. This domestic pathos, rather Ware-like, borders monsters and prodigies. The resulting spread is funny, yet sad. It's hard to tell whether Pearson's tone is a surrender to the familiar alt-comix vibe of melancholy and isolation, or a rejoinder to it: a reminder to open one's eyes and engage the world, in all its teeming strangeness. The anxiety feels genuine enough (and anxiety does come readily to Pearson: check out, e.g., this comic, or this one). I like the way the layout here reinforces the tonal ambivalence: the spread might be read as three more or less even tiers stretching horizontally across the page gutter, but for uneven borders that confuse our linear progress, jumbling the flow as we approach the bottom right corner. All this leads to a suggestive final panel that depicts our would-be suicide driving away, away, toward the page turn. The fantastical quirks in Everything We Miss – the bizarre critters and happenings just beyond human sight – live on in the brighter world of Hilda, with its matter-of-fact approach to mystery and magic. Hilda has become Pearson's calling card: thus far he has created four further Hildafolk albums (2011-2016), with more in the works. He has done a wealth of other things too (his website is, no kidding, a trove), but it's Hilda for which he's best known. In fact, since Nobrow launched its children's imprint, Flying Eye Books, in 2013, Hildafolk albums have become one of that imprint’s best-selling mainstays. And now, of course, there’s something else: an animated adaptation of Hilda has just joined Netflix’s lineup of original animated children’s series. As of September 21, it’s been possible to view the first season of Hilda, all thirteen 24-minute episodes, in Netflix’s usual bingeing way. Co-produced with London-born Silvergate Media and Ottawa animation studio Mercury Filmworks, this Hilda series involves Pearson as credited creator, co-executive producer, and occasional episode writer. That alone was enough to nudge me into renewing my lapsed Netflix account—and to inspire me to gather my Hildafolk albums into one place, the better to reread and review them. They warrant it. Bookmark KinderComics, then, for a series of posts that I’ll call “Reading (and Watching) Hilda.” This series will cover Hilda in print and on screen (including the just-published novelization of the TV series, by Stephen Davies). Stay tuned!

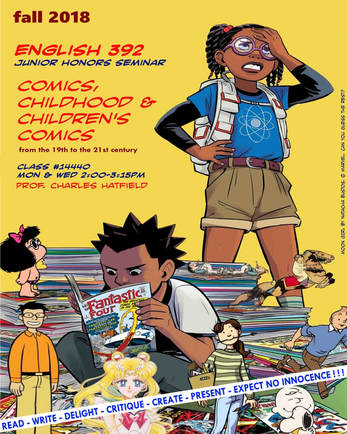

(The following statement opens the syllabus for English 392: Comics, Childhood, and Children's Comics, a course I am now teaching at CSU Northridge. English 392 launched on August 27, 2018, and we are at, roughly, mid-term. Regular KinderComics readers will recognize this post as one in a continuing series on teaching.) Did you know that Scholastic—publisher of Harry Potter, Captain Underpants, and The Baby-sitters Club—is also America's number one publisher of new, English-language comics? Not Marvel. Not DC. Scholastic. In fact, we are in a Golden Age of comics for children and young adults, in the form of the graphic novel. For about the past decade, graphic novels have been booming as a young reader's genre. Today, diverse publishers and imprints are competing to put graphic novels in the hands of children and teens: Graphix (Scholastic), First Second (Macmillan), Amulet (Abrams), Random House, TOON Books, Papercutz, BOOM! Studios, Farrar, Straus and Giroux BYR, Flying Eye Books (Nobrow), and others, including brand-new or forthcoming imprints CubHouse (Lion Forge), Yen Press JY, and even DC's soon-to-launch DC Zoom and DC Ink. In short, something interesting is going on. Who could have predicted this trend fifteen years ago? Comics, historically, have been a disreputable medium, branded as "objectionable," even as a threat to childhood, learning, and literacy. Further, the field of academic children's literature criticism (launched in the 1970s) has been so averse to comics that for decades it downplayed or ignored the form. The current interdisciplinary field of childhood studies has produced little work on comics. Even the field of comics studies, which has been exploding in the twenty-first century, has been so eager to attain legitimacy and "adulthood" (in terms defined by adult literature) that it has stinted research on children’s comics. Until quite recently, few scholars have felt the need to examine the intersection of comics and childhood. Yet comics have been central to the literacy stories, and reading lives, of millions of children the world over. Moreover, children's comics include many of the most influential comics ever published. Young readers have been the target audience of the most successful comics ever made—and those have been very successful indeed, in terms of profit, cultural influence, and deep connections made with readers. Comics for children are not new, even if we are now thinking of them in new ways. Many national cultures, from the Americas to Europe to Asia, have sustained long traditions of children's comics and drawn iconic images and characters from those comics (How can one understand postwar Japan without the manga of Tezuka, or contemporary France without Asterix?). In the United States, millions of readers young and old read comic strips in newspapers throughout most of the twentieth century, and the comic book, born in the Depression era, mushroomed by the end of the forties into an industry that sold tens of millions of magazines every month, most of them to young people. If comic books were disreputable, they were also hugely popular and influential. If many of us have almost forgotten that era, still it lives on, implicitly, in today's conversations about the graphic novel and children. Nowadays we see in comics the seed of a new visual literacy, complex and multimodal, but have the old fears gone away? Simply put, comics for children is a vital but still-obscured topic crying out for critical study—and that's what our English 392 class is all about. We will study the contemporary graphic novel as a children's and YA publishing phenomenon, and trace how and why this renascence has come about. In addition, we will consider (though alas only too briefly) the troubled history that lies behind this trend. What social, cultural, and educational changes have transformed the once-disreputable comic book into the graphic novel of today? What dynamics of power and cultural legitimization (or delegitimization) have changed the status of comics in our culture? To what extent has comics' reputation as illegitimate persisted, despite the current boom in children's comics? Together we will read articles and book chapters in children’s literature and comics studies, plus a range of children’s comics, from pioneering strips (e.g. Peanuts) to comic books to, most especially, contemporary graphic novels by authors such as Raina Telgemeier and Gene Luen Yang. As we work together, each of you individually will be able to find your own areas of interest and dig more deeply. Expect to present in class, i.e. lead class discussion, at least once during the semester; to pursue self-directed research responsive to your own interests; and to craft a final seminar paper roughly 10 to 12 pages in length. Expect several guest speakers as well!

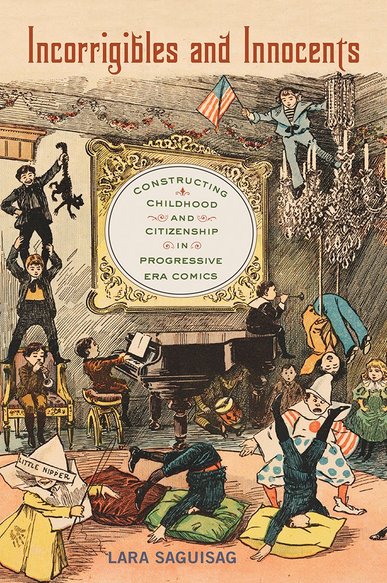

Sigh. About eleven weeks ago, I announced that KinderComics would be taking "a four-week break." That is, back around July 23 I envisioned that KinderComics would take a brief timeout so that I could prep my Fall classes and fix some technical problems, but then come roaring back to life by August 20. My hope, as I said, was "to get KinderComics on a more secure tech footing and then resume blogging on a biweekly basis just in time for the Fall semester." Further, I promised that KinderComics would "delve into teaching in a big way come August 20-27." Out of such promises, embarrassing retractions are made. August 20 would have been one week before the launch of classes at my school (CSU Northridge). As it happens, we are now in Week Seven of classes. Of particular interest to KinderComics is my Honors seminar, English 392, devoted to "Comics, Childhood, and Children's Comics." That course underwent much revision between the time of my last substantial post about it (gulp, May 31) and the launch of class on August 27. For example, four or five of the books I envisioned teaching in 392 have in fact dropped out of the syllabus, since I had to make more room for big issues and assignments (as a course designer, I'm used to that sort of change). As I've noted before, 392 is a bit of a balancing act: the impetus for the class is the current boom in young readers' graphic novels, but the class also seeks to "address the vexed larger history of children’s comics," including, briefly, "the histories of newspaper strips and comic books vis-à-vis children." As I've said, juggling those various topics is a challenge, both practically and intellectually. And now my students and I are right in the middle of that challenge! Working with the reality of 392, as opposed to planning it in the abstract, has required me to adjust my sights and hopes, so as to do the best I can by my students. What was a notional blueprint for a course has become, as it always must, an actual class and a kind of living experiment. I have begun to worry that my approach assumes too much prior knowledge, and to remind myself that any comics course at this level needs to lay a foundation, because students very often come into these courses with no prior experience of Comics Studies, and even little experience as comics readers (I am reminded of Gwen Tarbox's wise comments about gearing her comics-teaching toward her students' needs and concerns). In any case, I have certainly been mindful, these past seven weeks, of the serious challenge we have undertaken as a class. Here is the abridged course description for 392 that I gave out on paper back on Day One (the full syllabus being online, in the form of a class website): And here is the tentative schedule, also given out on Day One (the final schedule being on the class website, and always potentially in flux): Thus far we've kept to the rough contours of this schedule. On the one hand, we need some flexibility in scheduling; OTOH, the students have volunteered for dates to serve as discussion leaders (or "launchers"), so we do have to hold to the schedule as much as we can. Per the schedule, just yesterday we hosted the first of our four scheduled guest speakers: Dr. Lara Saguisag of the College of Staten Island-CUNY. Dr. Saguisag is an experienced children's author, longtime contributor to the Children's Literature Association, and author of the brand-new study, Incorrigibles and Innocents: Constructing Childhood and Citizenship in Progressive Era Comics (Ruters UP), which I consider a watershed book in both comic strip and childhood studies. I am sure that this is going to be an important and generative work for both children's literature and comics scholars. Having read both Dr. Saguisag's article on Buster Brown and some of her work on Peanuts this past week, we joined her via Skype for a freewheeling, spontaneous conversation about childhood studies, children's book publishing in the Philippines, early comic strips, and her research methods and process, as well as her passionate childhood reading (and perhaps more ambivalent adult assessment) of Hergé's Tintin and Lewis Carroll's Alice (with a sprinkling of Roald Dahl for good measure). It was a delight to witness Dr. Saguisag thinking aloud, on her feet as it were, about serious issues, including children's reading, its possible influence, the dark side of humor, and the resonance, or one could even say terrible relevance, of her book's findings for America today, an America once again obsessed with self and Other, inclusion and exclusion, and what it means to be a citizen. Speaking personally, I can't thank Lara enough for her forthrightness, openness, and thoughtfulness, and for her generous, accessible way with everyone in our class. It was a great session. By semester's end, we will have hosted, assuming all goes according to plan, three more speakers, including Skype guests Carol Tilley and Gina Gagliano and in-person visitor Jordan Crane (We Are All Me). To say that I'm looking forward to these sessions would be a huge understatement! What else have we been up to in 392? Well, besides delving into Peanuts and (via Lara Saguisag's work) early American newspaper strips, we've also discussed: the cultural status of comics in the US, in particular the comic book as defined by the scandals of the mid-20th century (this will lead to Dr. Tilley and other sources in a couple of weeks); the children's graphic novel boom (and the current status of graphic novels in public libraries); the introductions to two landmark scholarly books that came out last year, Picturing Childhood: Youth in Transnational Comics (ed. Heimermann and Tullis) and Graphic Novels for Children and Young Adults (ed. Abate and Tarbox); Joe Sutliff Sanders's "chaperoning theory" regarding the difference between comics and picture books, followed by Spiegelman and García Sánchez's Lost in NYC (2015) vis-à-vis De la Peña and Robinson's Last Stop on Market Street (also 2015); and Karasik and Newgarden's How to Read Nancy (2017), alongside, of course, a fair serving of Ernie Bushmiller's Nancy (and Jared Gardner on the history of comic strips). So, it's been a heady brew: history, current events, comics form, constructions of childhood, and more. And we're not even halfway through! Given all this, and three other courses to teach, in addition to writerly, editorial, and service commitments on multiple fronts, I'm forced to admit that maintaining even a biweekly blog is probably going to be beyond me between now and December. On top of that, the technical problems I alluded to back in July have not changed at all (Weebly continues to be anathema to my university), and I may therefore have to make some tough choices, and soon. But KinderComics is not going away; I hope to be back with reviews before Halloween. I continue to read children's and young adult comics (as well as many other sorts of comics) with the usual trancelike fascination, and look forward to sharing my thoughts here -- and, I hope, to hearing from my readers! PS. They are not "children's" texts per se, not in the usual, expected sense anyway, but I'd be remiss if I didn't point my readers to two extraordinary works in comics that I've read this past week, one a memoir of childhood to adulthood, the other a story about childbearing and birthing:  L. Nichols's booklength graphic memoir, Flocks, tells a story of growing up queer, and wracked with guilt, in a fundamentalist community. It's not a screed; it's not an act of revenge. Rather, it's an act of love, through and through, one that transmutes pain into courage and understanding. An achingly personal testimony to the work of transitioning and self-fashioning, it finds its own visual language, its own distinctive vocabulary of braided metaphors, to tell a story of self-in-community, of what it means to find yourself within (and against) your "flocks." Brave, tender, and astonishing. Bless publisher Secret Acres for bringing us the completed version of this long-awaited project.  Just as astonishing, though wholly different, is Lauren Weinstein's graphic memoir of her second childbearing and birthing experience, "Mother's Walk," which makes up the latest issue (No. 17) of Youth in Decline's outstanding quarterly anthology, Frontier. "Mother's Walk" is an explicit and revealing remembrance of childbearing and delivery, with all its rigors, emotional, psychological, and of course physical. I have been anxious to see a graphic memoir like this for some time, one that depicts birth and mothering in raw but loving detail. This is a startling, eloquent, and, as always with Weinstein, unpretentious and gutsy piece of work, one that (she says) anticipates a longer book about childbearing and child-rearing. I can't wait. I recommend these two titles as emphatically as I can recommend any art. PPS. It’s back in print: Joe Lambert’s Annie Sullivan and the Trials of Helen Keller. Ohmigosh, yes.

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed