|

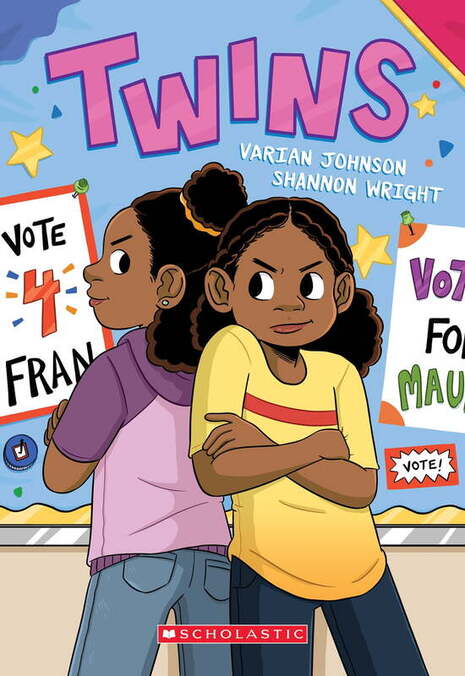

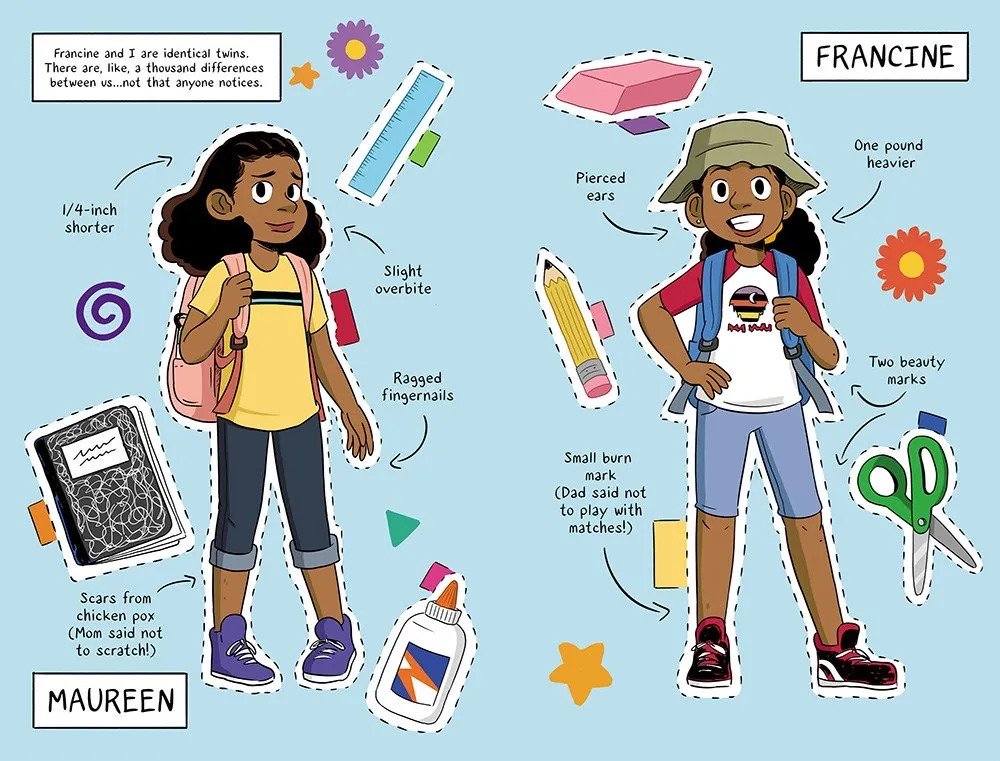

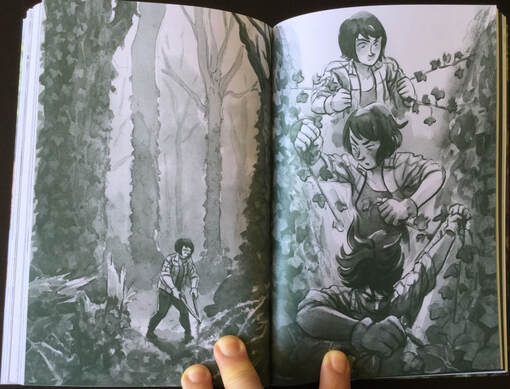

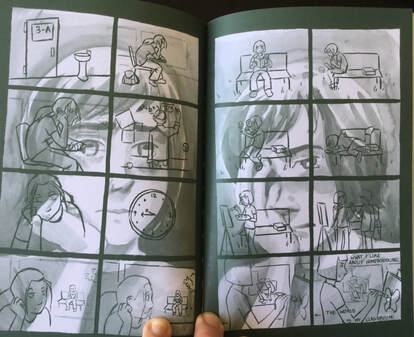

Twins. By Varian Johnson and Shannon Wright. Scholastic/Graphix, ISBN 978-1338236132 (softcover), 2020. US$12.99. 256 pages. Last week I belatedly read Twins, a much-praised middle-grade graphic novel published by Scholastic in 2020 — a first graphic novel for both writer Varian Johnson, who is a prolific novelist, and artist Shannon Wright, who has illustrated a number of picture books (most recently, Holding Her Own: The Exceptional Life of Jackie Ormes). Twins is good, but left me wanting more. The plot concerns identical twin sisters, Maureen and Francine, who have always been close but begin to pull apart as they enter sixth grade. They end up running against each other in a student body election, a rivalry driven by mixed or confused motives that hurts their relationships with friends and family. The book boasts many nicely observed, sometimes poignant, details: novelistic good stuff. The plotting balances the twins' need for individuation against their strong bond, with a sense of earned insight for both sisters. There are astute cartooning choices along the way, including full-bleed splash pages that capture moments of struggle, hurt, and growing realization. Compositionally, Wright delivers, with emotive characters, startling page-turns, and a confident grasp of what's at stake dramatically. Twins, I admit, strikes me as more reassuring than challenging. It's on familiar middle-grade turf, with a story of girls becoming tweens and growing more sensitized to social nuances and strained friendships. There are soooo many graphic novels currently working this turf. The setting is anodyne: a comfortably middle-class suburbia with dedicated students, supportive teachers and families, wise parents, and lessons on offer about self-discipline, self-confidence, and leadership. Loose ends are tied and every arc resolved, or at least reassuringly advanced, by book's end, with no one coming off the worse. Some elements, however, seem under-thought or cliched — for instance an ROTC-like "Cadet Corps" at the school, a plot device that allows for a fierce, drill sergeant-like teacher and moments of tough discipline for the more timid of the two sisters, who of course comes out the stronger (but oh the unexamined militaristic overtones). The book is inclusive and aims to be progressive, focusing on protagonists of color (Maureen, Francine, and their family are Black) while downplaying the usual generic thematizing of racism and classism as "problems" to be suffered through (a tendency expertly spoofed by Jerry Kraft in New Kid). One scene deals with shopping while Black and implies a critique of unspoken racism, but that thread isn't woven through the whole book. That in itself might be refreshing; the book thankfully avoids potted depictions of racialized suffering and trauma. Yet for me there is too little sense of social or institutional critique; the twins' relationship and personal growth are the main things, to the point of presenting adult choices uncritically and tying up the story without any lingering sense of mystery or depths remaining to be plumbed. In a word, it's pat. Perhaps I'm guilty of wanting this middle-grade book to be more YA? That wouldn't be fair, of course. But Twins is one of so many recent graphic novels that, from my POV, appear boxed in by children's book conventions, more specifically by the rush to affirm and reassure. The contours of this kind of book are starting to seem not just clear, but rigid. Young Adult books too have their conventions, one being skepticism of adult choices and institutions, and I don't know if I'm asking for that. Perhaps what I'm wishing for is something else: a touch of mystery, maybe, or a respect for the unfinished business of living. Twins is a traditional tale well told, with all its arcs well finished and its major characters affirmed and advanced. I just can't imagine re-reading it for pleasure. Some readers will stick to the book like glue, I expect. The characterization of the twins is complex, and Maureen, who is the book's focal character and real protagonist, is especially well realized: a socially anxious nerd and academic overachiever but not a shrinking violet, not a cliché. Johnson and Wright know these characters and treat them kindly; their dialogue clicks. Plus, the art is full of smart touches, and Wright offers clear, crisp cartooning and dynamic layouts throughout. Some moments registered very strongly with me: for example, the scene early in the book where Maureen and Francine get separated at school and a page-turn finds Maureen stranded in a teeming crowd of other kids, lost. Yet the book's brightness and formulaic coloring, which favors open space, solid color fields, abstract diagonals, and color spotlights, strike me as simply functional, and in the end more busy than harmonious. While Wright excels at characters, the settings appear textureless and a bit bland. Her page designs are restless, inventive, and clever, the storytelling clear, yet the governing sensibility seems, again, generic to my eyes. It's right in the pocket for post-Raina middle-grade graphic novels, but doesn't grip me. The middle-grade graphic novel is one of the most robust areas in US publishing, and the novel of school, friendship, and social navigation is its nerve center. Twins is a fine example of that. I think I'm becoming more and more jaundiced about that kind of book, though. I can now see the outlines of a formula, and I'm getting jaded. I admit, this realization has me rethinking the bright burst of enthusiasm with which I began Kindercomics five years ago.

0 Comments

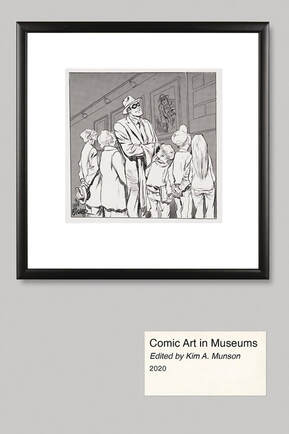

Despite the ravages of COVID, I feel optimistic about my field, comics studies, and glad to be part of it. Important, eye-opening research continues apace, and my understanding of the field keeps getting bigger (which is to say that I keep getting challenged, in invigorating ways). The scholarly institutions I’ve been part of are doing what they can to bring communities together in spite of the pandemic. Academic conferences, independent comics festivals, and large-scale comic-cons have offered virtual programming this past year, so that life and study at home don’t seem quite so lonesome. I’m particularly happy to see the International Comic Art Forum’s slate of monthly virtual events, still ongoing, and the call for next summer’s Comics Studies Society conference. On a personal note, this year saw, at last, the publication of a long-term project of mine, Comics Studies: A Guidebook, a classroom-ready anthology co-edited with Bart Beaty (and published by Rutgers University Press). Bringing this book into the world took many years, but I'm proud of the results: essays by twenty scholars on the history, form, genres, production, and reception of Anglophone comics. These essays succinctly explain fundamental issues in the comics studies field, crystallizing complex questions, if I may say so, in ways that no book has done before, and often with real conceptual originality. I thank our contributors for their steadfastness, patience, and brilliant writing; the life of the Guidebook is in their essays. If you're a student or teacher of comics, I hope you'll check our Guidebook out. Again speaking personally, I had the pleasure to contribute to another comics studies volume this year, Kim Munson's Comic Art in Museums (published by the University Press of Mississippi), a groundbreaking collection focusing on the exhibition of comics in museums and galleries. If you want to know more about how comics came to be exhibited and recognized in the art world, then this book can give you a grounding. The history that Munson and her contributors lay out is longer and more complex than you might expect. (I am honored to have two pieces in the book, and to have curated the 2015 Jack Kirby exhibition that is the focus of several pieces.) What follows is a handful of comics studies books that I'm currently reading, books that I find particularly exciting at this moment. This is not meant to be a best-of for 2020, since, goodness knows, I've had trouble keeping up academically during the long lockdown (and there are new books that I haven't had a chance to dive into yet, such as Anna Peppard and company's Supersex: Sexuality, Fantasy, and the Superhero, or Frederick Luis Aldama et al.'s massive Oxford Handbook of Comic Book Studies). These are just a few of the books that recently struck me as expanding the boundaries of the field: Sean Kleefeld, Webcomics (Bloomsbury). Eszter Szép, Comics and the Body: Drawing, Reading, and Vulnerability (The Ohio State University Press). Disclosure: I co-edit, along with Jared Gardner, Rebecca Wanzo, and acquiring editor Ana Jimenez-Moreno, the OSUP's Studies in Comics and Cartoons series, which published Szép's book.) Gwen Athene Tarbox, Children's and Young Adult Comics (Bloomsbury). Rebecca Wanzo, The Content of Our Caricature: African American Comic Art and Political Belonging (NYU Press). Paul Williams, Dreaming the Graphic Novel: The Novelization of Comics (Rutgers UP).

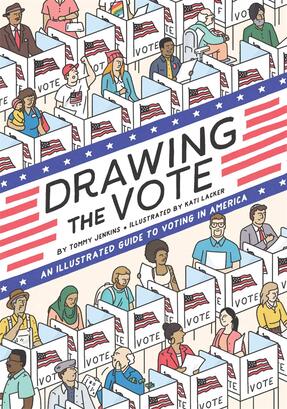

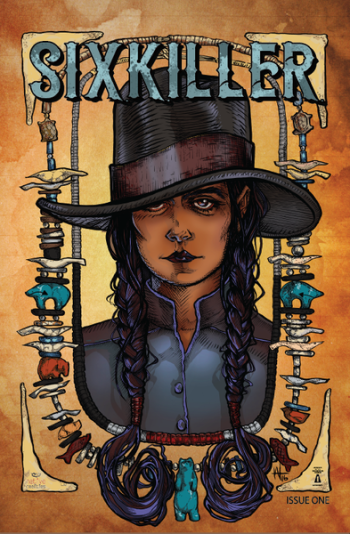

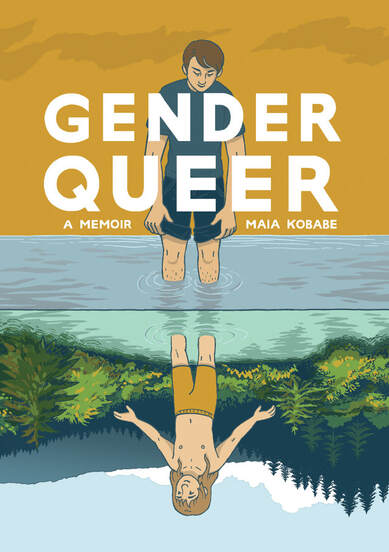

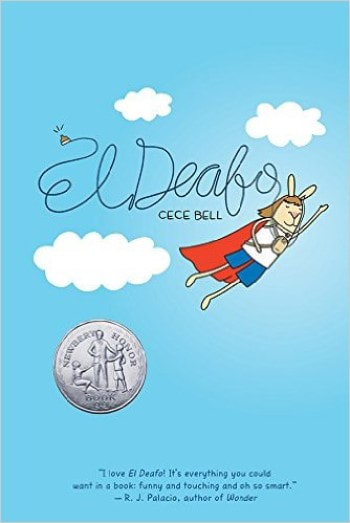

A partial list, forever in progress (every week I learn about new stuff)!(This Election Week post grew out of queries from colleagues as well as virtual teach-ins at CSU Northridge. It is very much a quick, tentative dispatch!) Below is a bunch of notes, roughly organized, about comics (especially graphic novels) that engage urgent social issues such as voting, migrant and refugee experience, racism, police violence, political activism, gender, feminism, and LGBTQ+ activism. Note that not all of these books are designated as children's or young adult books, and many contain frankly adult content. OTOH, there are some excellent young reader's books here. Besides long-form comics like graphic novels, other, shorter comics may engage such issues too, webcomics in particular. Webcomics are typically free and often address vital issues briefly and powerfully; e.g., consider the many affecting comics about living under COVID (see especially the series “In/Vulnerable,” on thenib.com, researched by reporters for The Center for Investigative Reporting and drawn by Thi Bui: https://thenib.com/in-vulnerable/). The Movement for Black Lives and the Black Comics Explosion  March, by the late John Lewis, with collaborators Andrew Aydin and Nate Powell — a memoir trilogy about Lewis’s participation in the Civil Rights Movement. One of the most acclaimed of recent American comics, and highly recommended. “Your Black Friend,” by Ben Passmore, a short satirical comic found in his book Your Black Friend and Other Strangers. Also, see Passmore’s collaboration with Ezra Claytan Daniels, BTTM FDRS, an urban horror story and satire about gentrification—it’s gross and very good! (I’d check out anything by Passmore, though he may not appeal to everyone, and some of his more underground-like work is a mixed bag. He has a new graphic novel called Sports Is Hell that I haven’t read yet. Be sure to look for Passmore’s online comics, especially on The Nib. He often engages issues of police violence and critically engages the BLM movement.) Damian Duffy and John Jennings adapted Octavia Butler’s classic novel Kindred into a graphic novel: a heartfelt piece of work about time-traveling back into the era of slavery. They have recently adapted another of Butler’s novels, Parable of the Sower, but I haven’t read it yet. Speaking of Jennings, he and fellow artist Stacey Robinson together drew the graphic novel I Am Alphonso Jones, written by Tony Medina—the story of a young Black man killed by police. This is often categorized as YA. Hot Comb, by Ebony Flowers, combines memoir and fiction: a series of short, intimate stories, many exploring the consequences of racist beauty standards for Black women. Understated, powerful. Sometimes also categorized as YA. See Jerry Craft’s New Kid for a funny, insightful middle-grade GN about being a scholarship kid of color in a tony private school. (Craft has a new book, Class Act, that I haven’t read yet.) Bitter Root, by Chuck Brown, David Walker, and Sanford Greene, is an ongoing comic book series that filters period pulp action through African American historical and cultural lenses. There are two collected volumes so far. It’s overtly political even as it dishes out monster-smashing action: an Ethno-Gothic, steampunk, antiracist adventure. Cool. (Not understated!) Great African American SF/fantasy novelists like Nalo Hopkinson, Nnedi Okorafor, and N.K. Jemisin have been writing superhero comic book serials lately. Jemisin is about 2/3 of the way through a Green Lantern series with many topical elements titled Far Sector, drawn by Jamal Campbell. It concerns race and the challenge of living in a pluralistic society (a faraway world inhabited by billions of beings of several different species). Smart, rich work. Immigrant and Refugee Experience Alberto Ledesma shares reflections from his life as an undocumented immigrant in Diary of a Reluctant Dreamer, a very personal scrapbook of sorts that grew out of a series of Facebook posts. Eye-opening for me, and poignant. Besides superheroes, Nnedi Okorafor has written a SF comic called LaGuardia that deals with immigration and nativist backlash—but on a planetary level! It’s drawn by Tana Ford. Escaping Wars and Waves, by graphic journalist Olivier Kugler, depicts Syrian refugees living in refugee camps, and is excellent. Border: A Crisis in Graphic Detail, edited by Mauricio Alberto Cordero, is a recent comics anthology about migrant experience at the US’s southern border, and a fundraiser for the South Texas Human Rights Center. Powerful stories and testimony. The Scar, by Andrea Ferraris and Renato Chiocca, is a brief but powerful treatment of the US/Mexico border. Migrant: Stories of Hope and Resilience, written by Jeffry Korgan and illustrated by Kevin Pyle, recounts personal stories of crossing the US border (I haven’t had a chance to read it yet). Thi Bui’s graphic memoir, The Best We Could Do, about five generations in the life of a Vietnamese American family, is brilliant, a great book. (Matt Huynh’s webcomic Cabramatta resonates with this: http://believermag.com/cabramatta/. So does GB Tran's book Vietnamerica.) The recent YA graphic memoir by Robin Ha, Almost American Girl, depicts a Korean American experience that perhaps invites comparison. There are quite a few graphic memoirs about the experience of immigrants’ children—see, e.g., I Was Their American Dream, by Malaka Gharib. They Called Us Enemy, by George Takei, Justin Eisinger, Steven Scott, and Harmony Becker, is an autobiographical account of the incarceration of Japanese Americans during WW2. Much to learn here. Immigration policy is discussed in Open Borders: The Science and Ethics of Immigration, by Bryan Caplan and Zack Weinersmith, though I haven’t gotten to read it yet. It’s a didactic graphic book: less story than argument. But there are many great comics like that! Comics on the Political ProcessUnfit: How to Fix Our Broken Democracy, by Daniel Newman and George O’Connor—though I’m afraid I haven’t read this yet. Drawing the Vote: An Illustrated Guide to Voting in America, by Tommy Jenkins and Kati Lacker. Comics about Indigenous LivesFor comics by Indigenous creators, see for example the anthology Moonshot, and check out publisher Native Realities: https://redplanetbooksncomics.com/collections/native-realities. In particular, the collaborations of artist Weshoyot Alvitre and writer Lee Francis IV (e.g., Sixkiller; Ghost River: The Fall and Rise of the Conestoga) have captured my attention. Look also for the anthology Deer Woman, co-edited by Alvitre and Elizabeth LaPensée. A recent scholarly collection, Graphic Indigeneity, ed. Aldama, will help here. Celebrated comics journalist Joe Sacco (who produces one stunning book after another) has just recently published Paying the Land, a book about resource extraction and energy politics, but most particularly the history of an Indigenous Canadian people, the Dene. I’ve read only the opening chapter so far (which is remarkable) but the book looks ambitious and informative. Know that Sacco is not an Indigenous author (he is Maltese-American), and scholar colleagues versed in this area have shared some eye-opening critical points with me; still, Paying the Land will surely be worth your time. Gender and Sexuality (Feminist, Queer, and Trans Perspectives)Drawing Power, edited by Diane Noomin, is a stunning anthology of stories about sexual violence, harassment, and survival. Strong, stinging, varied work there, sometimes harrrowing—a response to #MeToo. Maia Kobabe’s nonbinary memoir, Gender Queer, is tender and revelatory. You could call it a YA book, though of course its reception in YA circles has been fraught. (It's a frank depiction of, among other things, gender expression and sexual exploration — so, well, let's just say that some Amazon customers disapprove.) Look for the LGBTQIA anthology Love Is Love, a 2017 benefit to help victims of the Orlando nightclub shooting—short comics, but often powerful, and varied in approach. Justin Hall’s No Straight Lines: Four Decades of Queer Comics is essential history. Edie Fake's Gaylord Phoenix is a mind-altering, phantasmagorical quest fantasy from a trans perspective: a mostly wordless transition fable that rewrote the way I think about comics! Highly recommended. (Be aware: this is not tagged as a young reader's book, and includes startling images of violence and self-harm as well as sexual abandon.) Disability, Graphic Medicine, and CareCheck out the graphic medicine movement, devoted to comics treatment of illness, wellness, and dis/ability: see https://www.graphicmedicine.org. Note also the prevalence of disability memoirs in comics that are not medical in focus, e.g. Cece Bell’s great children’s comic, El Deafo; or the very recent (fictionalized) YA book, The Dark Matter of Mona Starr, by Laura Lee Gulledge, about depression; or any number of webcomics about life on the autism spectrum. Kabi Nagata’s manga My Lesbian Experience with Loneliness concerns not only sexuality but also anxiety and depression. Allie Brosh’s work also addresses depression and anxiety (Hyperbole and a Half; Solutions and Other Problems). Katie Greene’s Lighter Than My Shadow depicts her life with anorexia and an eating disorder. I highly recommend Vivian Chong and Georgia Webber's collaborative memoir, Dancing after TEN, which recounts a life-changing medical crisis for Chong that robbed her of sight; as well as Webber's own solo book about literally losing her voice, Dumb. Re: aging and elder care, see such graphic memoirs as Roz Chast’s Can't We Talk about Something More Pleasant? and Joyce Farmer’s Special Exits. Just a random recommendationFor depiction of progressive activism in a near-future dystopia, basically just a few steps from our own, read The Hard Tomorrow, by Eleanor Davis. This one rattled me, and it's beautiful. One last note (preaching to the choir?)As many KinderComics readers may know, children’s and young adult graphic novels are the fastest-growing, most robust sector of comics publishing in the US. They often deal with complex immigrant or minority experience, and offer queer-positive portrayals as well. Check out anything by Mariko Tamaki, Jillian Tamaki, Jen Wang, or Tillie Walden. This publishing movement is really doing bold new things in queer representation and identity narrative.

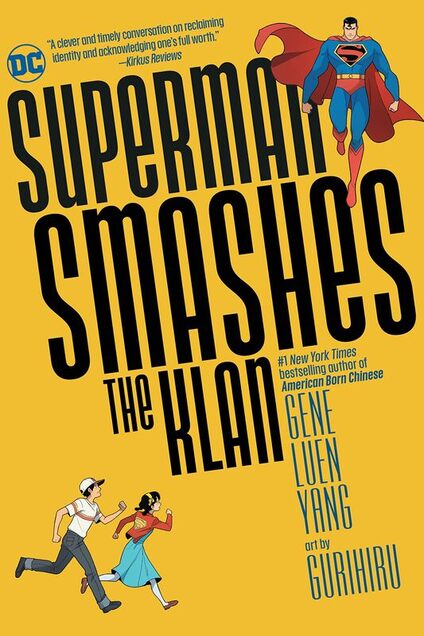

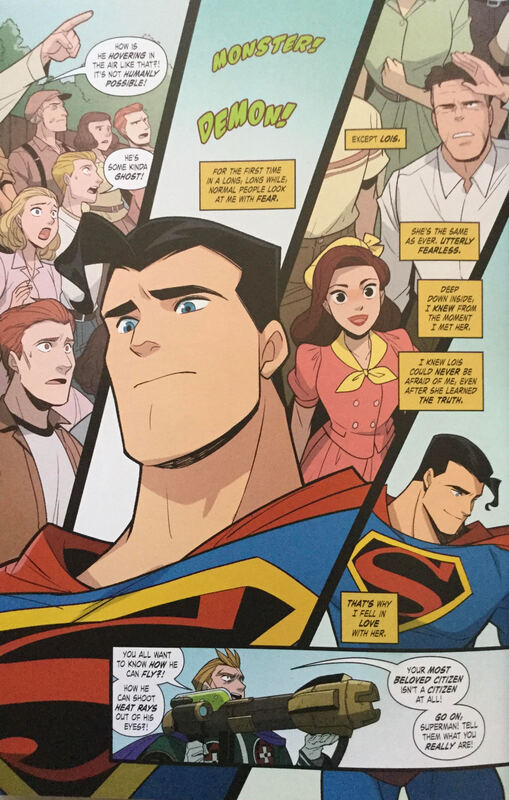

Superman Smashes the Klan. By Gene Luen Yang and Gurihiru. Lettering by Janice Chiang. DC Comics, ISBN 978-1779504210 (softcover), May 2020. US$16.99. 240 pages. (The first in an occasional series reviewing children’s and Young Adult graphic novels from DC.) One of the pleasures of reading Gene Luen Yang is watching him play — and take risks — with sources. American Born Chinese gives the Chinese literary classic Journey to the West an Americanized (and Christianized) spin, while riffing on sitcoms, Transformer-style mecha, and Yang’s own boyhood as an immigrant’s son. The recent Dragon Hoops (reviewed here in March) folds the history of basketball, reverently sourced, into its account of Yang’s last year as a high school teacher. Yang’s five-volume run on Avatar: The Last Airbender (2012-2017), his first collaboration with Japanese art team Gurihiru (Chifuyu Sasaki and Naoko Kawano), is a sequel to the beloved TV series (2005-2008). The Shadow Hero, Yang’s 2014 graphic novel with artist Sonny Liew, revives an obscure Golden Age superhero, Chu Hing’s Green Turtle (1944-1945), giving him a new origin and feel. Yang’s latest, Superman Smashes the Klan (now gathered into one volume, after a three-issue serial release last year), draws from an antiracist storyline in the Adventures of Superman radio serial in 1946, but adapts it freely. Superman Smashes the Klan interweaves several threads from Yang’s previous work. Once again, he plays with DC Comics and Superman lore; again, he collaborates with Gurihiru. Once more, as in The Shadow Hero, he treats the superhero-with-secret-identity as an overt assimilation fantasy, in a period American setting. It’s the best of his DC projects by a long shot: the most obviously personal, the most graphically whole, consistent, and readable. It’s also, I think not coincidentally, the one that comes closest to the children’s and YA graphic novel genre that Yang is best known for. This is one of the more interesting of the many 21st-century reinterpretations of Superman’s origin. It happens that my wife and I have been reading it at the same time as another reinterpretation, Tom De Haven’s prose novel It’s Superman! (2005). De Haven’s is a free retelling of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster’s original, late mid-1930s Superman, done up as nerdy, name-dropping historical fiction in the vein of Michael Chabon’s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay (2000). It’s Superman! digs hard into that vein, stressing economic misery, political unrest, migration, segregation, and pervasive everyday racism in tune with its Depression-era setting. Also, it’s peppered with cameos by real-world people, neighborhoods, architecture — you name it, De Haven has researched it. Add in sexual knowingness, lurid violence, and odd character studies of crooks and victims, and you’ve got a very “adult” riff on the Siegel and Shuster model, something not too far from De Haven’s other comics-themed historical novels. Don’t get me wrong: It’s Superman! is a terrific book, one I’d like to teach when I get around to doing an all-Superman course. I think it would teach well alongside Superman Smashes the Klan, as both replay Superman’s origin in early 20th-century period (the mid-30s for De Haven; 1946 for this book) — and both stress Clark Kent’s moral education, his growing awareness of social injustice. Yet the two books are quite different. De Haven’s Clark never finds out where he came from; though he suspects that he is not from Earth, he never learns about planet Krypton. The book only hints at Clark’s origins. De Haven works hard to suggest how this lonely, alienated young man might turn to reporting, and to his unrequited love for Lois Lane, as a way of becoming “just like everybody else.” Yang and Gurihiru’s Clark, on the other hand, learns more about his extraterrestrial origins — there’s more SF in his story. He too, though, longs to be like everyone else, to assimilate — so much so that he hides his light under a bushel, downplaying or even failing to recognize some of his powers. He befriends young Roberta and Tommy Lee, children of a Chinese immigrant family that has just moved to Metropolis, and combats a militant, White supremacist Klan group that terrorizes them. At the same time, he must confront his fears of revealing his own alienness, and frightful visions of himself and his birth parents as green-skinned monsters. This Clark starts out not knowing about Krypton, but gradually learns of it (through a familiar plot device: a bit of leftover Kryptonian tech). In the course of fighting the Klan, Clark discovers the full extent of his powers, hidden from him by his own desires to assimilate: a clever way to explain how the running and jumping Superman of early Siegel and Shuster became the flying Superman with X-ray vision that we know now. But much of the story belongs to young Roberta (Lan-Shin) Lee, whose worries about fitting in mirror Clark’s, and whose empathy with him proves key to unlocking his potential. Yang and Gurihiru give us brief flashbacks to Clark’s origin, while focusing on his anxious way of passing among humans in the present — an anxiety Roberta knows all too well. The book's nonlinear retelling deftly frames the old origin story as a fable of assimilation (à la The Shadow Hero). Roberta and Clark, both immigrants uncomfortably aware of their alienness, together foil the Klan and stand up for a vision of Metropolis — implicitly of America — in which everyone is “bound together,” sharing the same future, “the same tomorrow.” In this way, Superman Smashes the Klan makes its antiracist parable integral to Superman’s own process of becoming. Superman Smashes the Klan is not subtle; after all, it’s a value-laden fantasy of nation, like so many American superhero comics — and it obviously courts a young audience (Young Adults, says the back cover, but I’d say middle-grade). The book wears its values on its sleeve. Also, the period setting seems idealized: for example, Inspector Henderson of the Metropolis PD is here portrayed as African American, which tends to suggest a very progressive Metropolis for 1946, one in which the Klansmen’s anti-Black racism makes them outliers. This may be too easy. Though the story acknowledges that racism takes many forms, the masked Klansmen provide an obvious, simplistic focus (I’d expect a YA novel about racism to be more ambiguous and challenging on this score). On the other hand, the book allows some of its racist characters to grow: young Chuck, nephew of the Klan’s leader, learns to reject his uncle’s ways at the boffo climax — at which a bunch of kids help Superman save the day, own his identity, and face down xenophobia. Superman Smashes the Klan, then, dares to hope — as children’s texts so often do — that the openness and innocence of the young can redeem a society riven by bigotry and corruption. This utopian vision is familiar to anyone who studies children's literature; it's obvious. Yet, obvious or not, this is just the kind of Superman story I prefer to read, one in which Supes clearly stands for a decent, humane, inclusive ideal. It’s on the nose, sure, but that doesn’t bother me much. It could make a terrific animated film, in post-Spider-Verse mode (we can only hope). That said, Superman Smashes the Klan is not as effective, I think, as Yang and Liew’s Shadow Hero, which more daringly uses superhero tropes to create a layered, ambivalent assimilation story. This is a Superman comic, after all, hence constrained; the nervy, potentially offensive gambits in The Shadow Hero are not to be expected. Yet Yang has taken some interesting risks in reworking Superman’s origin; it’s good to see the truism that Superman is an immigrant being put to real use. It’s likewise good to see Superman sprung free — liberated — from the suffocating weight of “DC Universe” continuity. I'm a little sad that this has to happen in a distanced period setting, rather than a contemporary one. (I'd love to see this book spawn a series of timely, obviously relevant Superman GNs set in the present day, for the same audience.) Stylistically, I’ll say that I find the book a bit too clean and antiseptic to conjure the desired sense of period; Gurihiru’s neat, smart artwork strikes me as too textureless and bland to evoke a mid-1940s Metropolis. I’d have liked to see a grittier city setting, with more grimy particulars, so that Superman’s bright, heroic doings would stand out by contrast. On the other hand, Gurihiru’s pages are dynamic, inventive, and ever-readable. The book combines the snazziness and roughhousing energy of most superhero comics with clear-line legibility. It’s fetching and fun to look at, and Yang and Gurihiru are clearly sympatico (their Avatar collaboration obviously prepared them for this). If only most DC comics were this free and confident of their aims. The recent news that Marvel is teaming up with Scholastic — that is, licensing Scholastic to produce a series of original graphic novels for young readers starring Marvel heroes, to be published under the Graphix line — gives me hope that we may see a flood of comics with similar aims. That announcement came as a surprise, but perhaps it shouldn't have: after all, young readers' graphic novels are the thriving sector in US comics publishing today. Maybe, just maybe, US-style superhero comics, not just movies, TV shows, and goods based on such comics, can once again become popular, widely available children's entertainment. Having lived through (and, for a time, invested emotionally in) the revisionist adultification of superheroes in the 1980s to 90s, I find this prospect oddly exhilarating. I wonder what Yang thinks — and if he is keen to do more books of this type. Man, what I wouldn’t give to teach a sequence like so: Siegel and Shuster’s first two years of Superman (1938-1940), De Haven’s retake, The Shadow Hero, and Superman Smashes the Klan. I bet that would kick off some great conversations. PS. Gene Luen Yang has been on the board of the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund since 2018. In light of the infuriating recent news out of that troubled organization, his frank and reflective remarks on Twitter have been illuminating. Yang — wisely, I think — values the Fund's mission over the current organization, while also pointing out the good work done by current CBLDF staffers. It's quite a tightrope walk — and recommended reading for those who've been following the news of the CBLDF, and the comic book field's larger sexual harassment and abuse crisis, on this blog. PPS. Gene Yang is slated to take part in three virtual panels at this week's Comic-Con@Home: The Power of Teamwork in Kids Comics (today, Wednesday, July 22); Comics during Clampdown: Creativity in the Time of COVID (Thursday, July 23); and Water, Earth, Fire, Air: Continuing the Avatar Legacy (Friday, July 24). These events, like most panels making up Comic-Con@Home, will presumably be prerecorded, hence without live audience Q&A, which is a shame. But, still, there should be some interesting back-and-forth among the panelists, and Yang is a great ambassador and thinker on the fly. See comic-con.org or Comic-Con's YouTube channel for further info.

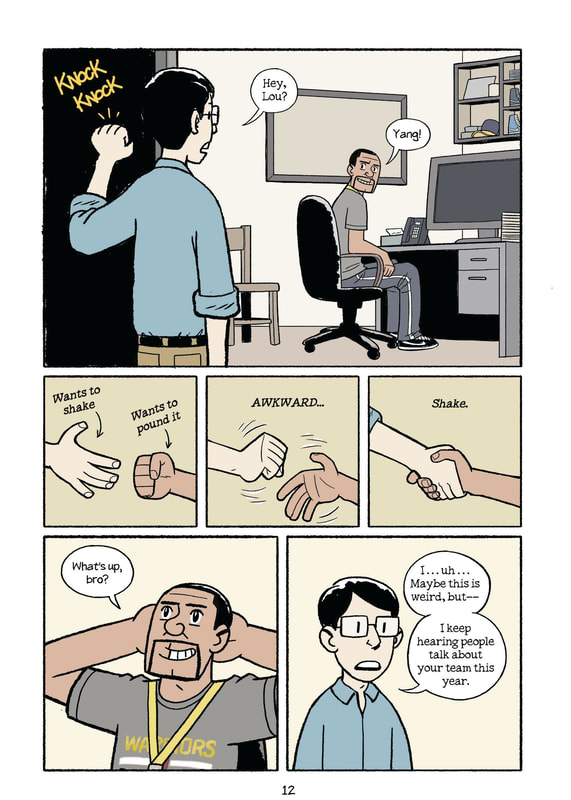

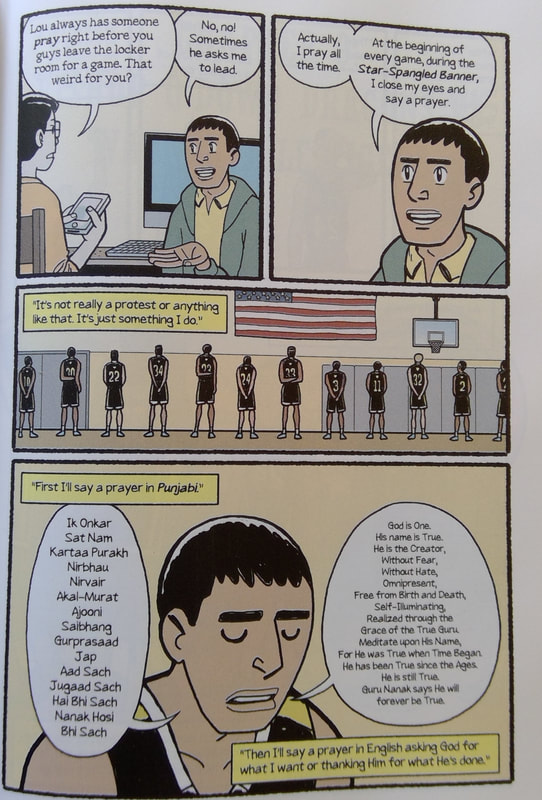

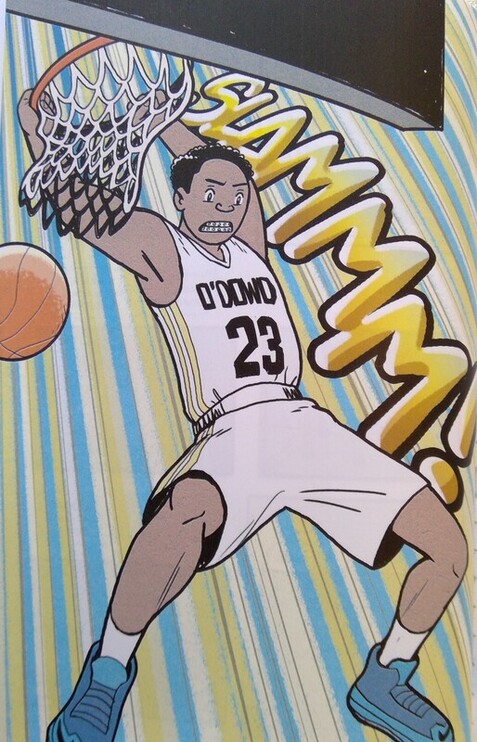

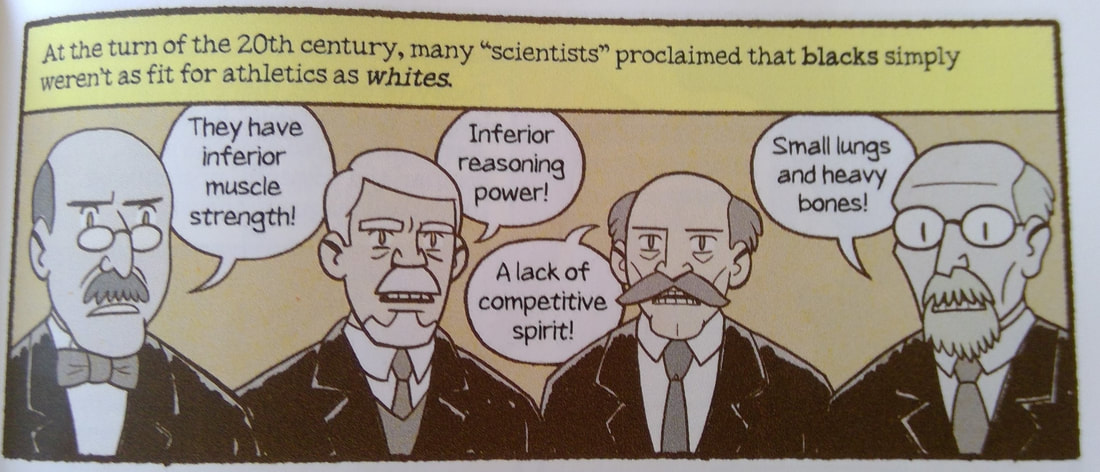

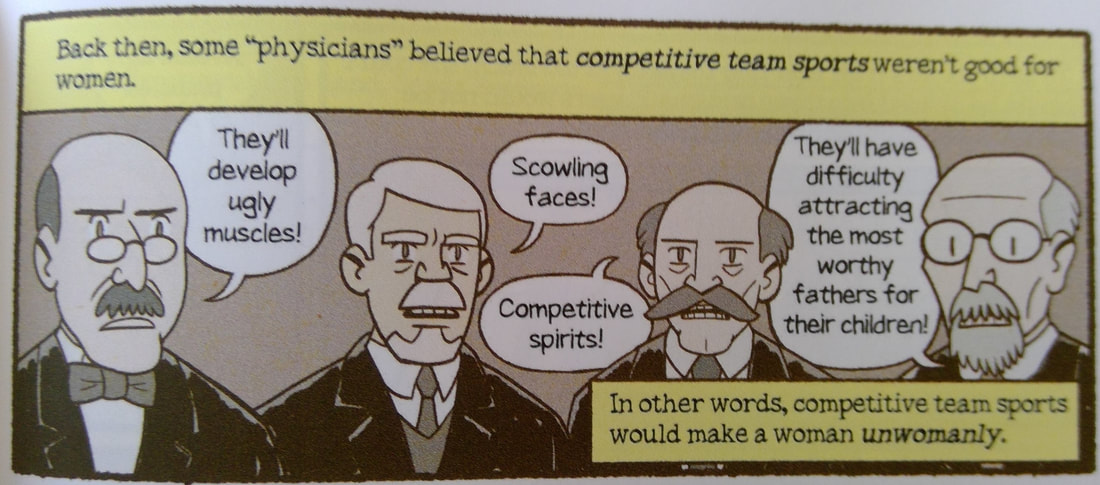

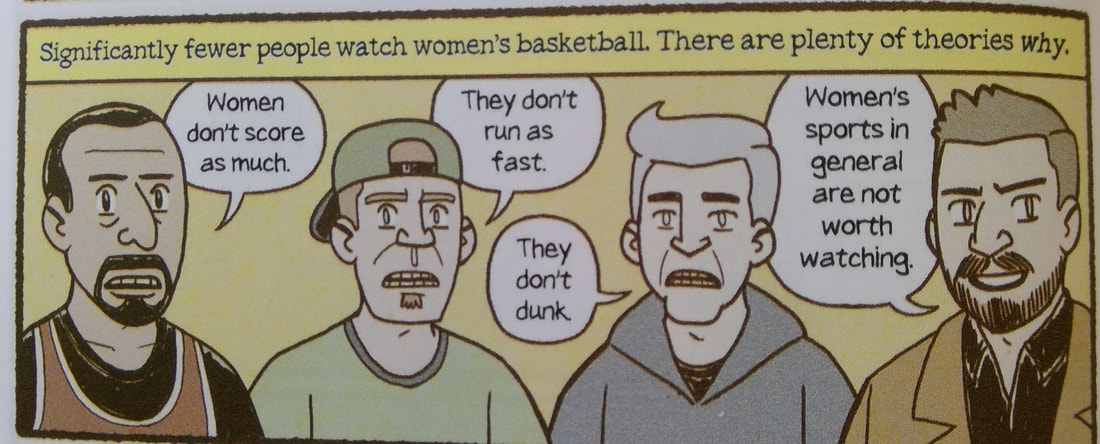

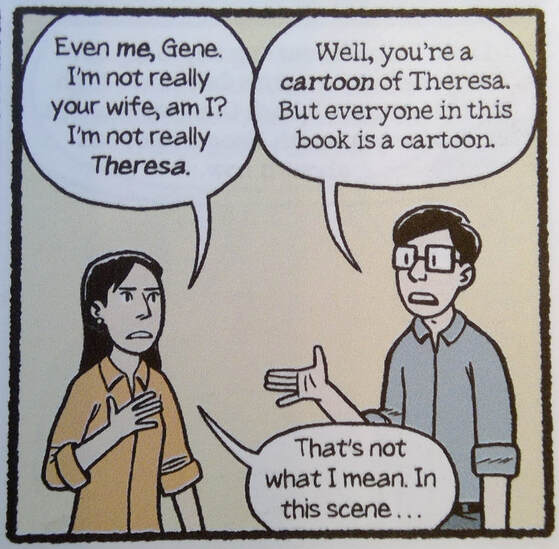

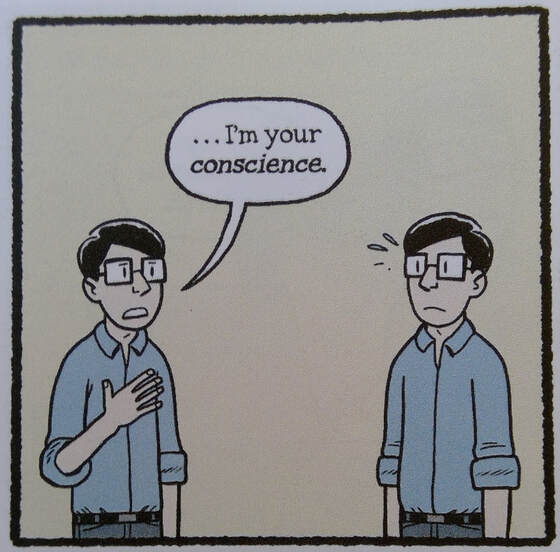

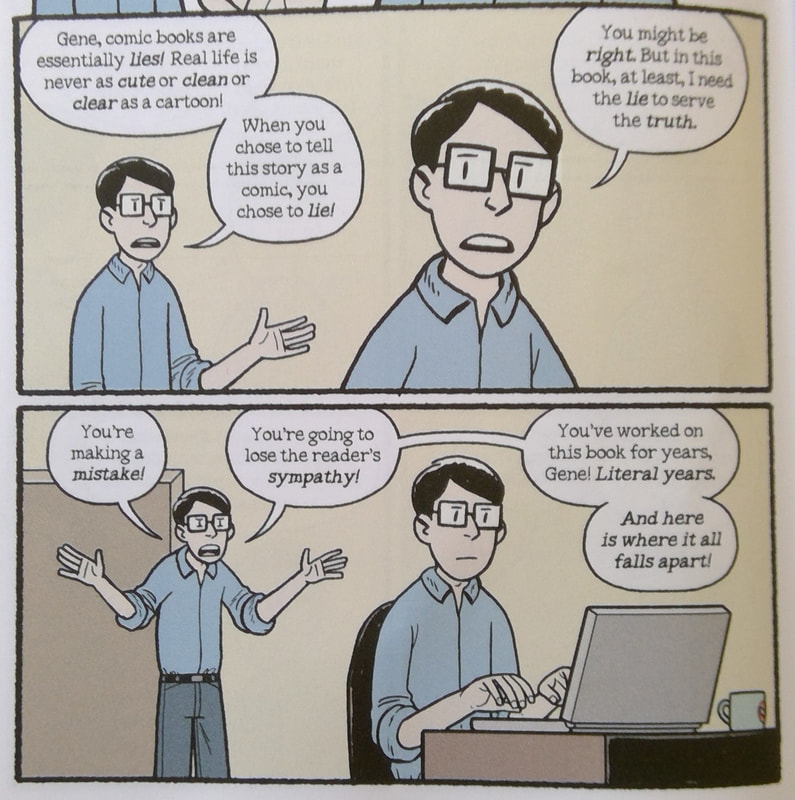

Dragon Hoops. By Gene Luen Yang. Color by Lark Pien. First Second. ISBN 978-1626720794 (hardcover), $24.99. 448 pages. March 2020. Recently Gene Yang has been out touring in support of his newest graphic novel, the just-released Dragon Hoops. But of course he hasn't been touring in the flesh; the COVID-19 pandemic has had him—like so many of us—holed up at home, trying to find creative new ways to engage with both his family and his public. Happily, he hit upon the idea of a virtual book tour: that is, promoting Dragon Hoops through a series of Instagram comic strips in which he responds to readers’ questions. These quick comics are formulaic, but the formulas are clever and engaging: Yang repeats shots and gags across the series, making it feel much like whistle stops before a loving audience that tends to ask the same few questions again and again. Of course, these comics are self-deprecating—more than anyone else, Yang is the object of his own jokes. He makes an excellent comic strip character. Humorous self-deprecation is one of Yang’s constants. He used to self-publish under the imprint Humble Comics, and if you’ve seen him speak you know that he excels at genial self-mockery. Yang plays humble the way Liszt played the piano—it’s his instrument. But don’t let him fool you: he is a gutsy and ambitious narrative artist whose work walks a tightrope between charming accessibility and willed difficulty. Yang takes chances. In particular, his solo graphic novels (as opposed to his many collaborative works) are fearsome high-wire performances. Dragon Hoops is no exception. Yang’s comics tend to be structurally tricky, thematically bold, and psychologically sharp. His breakout book, American Born Chinese (2006), semi-autobiographical yet fantastical at once, interweaves three stories in three different genres, until a startling moment that turns those three tales into one. The novel oscillates between ingratiating humor and terrible pain (in fact, those two tones are co-present throughout). Mixing myth fantasy, earthbound middle-grade school story, and arch sitcom, American Born Chinese is great comics, capitalizing on the form’s stable-unstable, multimodal heterogeneity to tell an immigrants’ son’s story, one of divided identity or fractured self. At bottom, it’s a story about internalized racism and self-hatred. A nervy book, it freely adapts China’s legendary Journey to the West, while at the same time insinuating a Christian allegory and riffing on Transformer/mecha pop culture. Moreover, it dares a form of grotesque satire, in which hateful, grossly racist anti-Chinese stereotypes reflect the protagonist’s self-loathing (a strategy as impious and risky as Art Spiegelman's notorious animal metaphor in Maus). In sum, American Born Chinese revealed Yang’s propensity for large-scale structural conceits that enact his own ambivalence and complex sense of identity. It was, is, daring. Yang’s follow-up project, Boxers & Saints, goes one better. A two-volume novel about China’s Boxer Rebellion, it’s a magic-realist historical fantasy in which the twin volumes represent, in a kind of tense counterpoint, both Chinese nationalist (Boxers) and Europeanized missionary (Saints) perspectives. Pitting the story of a young man who is an anti-colonial revolutionary against that of a young woman who is a Christian convert, Boxers & Saints balances Yang’s Catholicism against his pained awareness of Western imperialism and racism, while also critiquing strands of misogyny in traditional Chinese culture. The resulting two-headed novel, rather shockingly violent for Yang, represents a dramatic argument: a psychomachia in which different facets of Yang contend with each other, bitterly. Boxers completes Saints, and vice versa, and both volumes sting. This project shows, again, Yang’s penchant for teasing out self-conflict by counterposing different plots (in this case, different books!) and engineering complex structures. Identity in his books is as tricky as the plots: dynamic and never settled, an anxious balancing act. Yang's ingenious plotting, and an overall sense of high personal stakes, of storytelling wrung from pain, transform what could be flatly didactic into harrowing stuff. Dragon Hoops aims for this quality too, though it lacks the big structural conceits of the three-part American Born Chinese or two-part Boxers & Saints. It differs in another important way too: this time the tale is not historic, mythic, or crypto-autobiographical, but instead a literal memoir, an account of a year in Yang’s life as a teacher at Bishop O’Dowd High, a Catholic school in the Bay Area. Dragon Hoops is the longest overtly autobiographical work Yang has done. Yet it’s really about (huh?) basketball: on one level, Bishop O’Dowd’s varsity men’s basketball team, the Dragons, hungry for a state championship, but more broadly the entire history of the sport and how it intersects with race, class, and even Catholic schooling. In short, Dragon Hoops takes on basketball as a social force. This is something that the book’s version of Gene, archetypally geeky and sports-averse, has to struggle to understand. The story follows Gene from standoffish sideline observer (he is, at first, simply a storyteller looking for a new story) to ardent booster of the school’s basketball squad. At the same time, it charts a major shakeup in Yang’s own life, and offers multiple stories of struggle and vindication if not redemption. Further, it explores ethical issues involved in coaching, mentoring young people, and even Yang’s own storytelling. In fact, Yang worries on the page about what he is doing on the page. Here the book seems boldest--or perhaps most vulnerable? Dragon Hoops is long and complex (at about a hundred pages longer than Boxers, it is Yang’s heftiest single volume). Somewhere between intimate memoir, journalism, and oral history, it profiles the players on Bishop O’Dowd’s team, observes the complex social dynamics of their lives, and sets us up for, yes, a nail-biting climax on the court, at the longed-for championship game. Simultaneously, though, it recounts the creation and democratization, or broadening, of basketball, in a series of historical vignettes—while also depicting a transformative moment in Gene’s uncertain career in comics. That career comes to a sort of fortunate crisis when Gene, startled and uncertain, is offered a chance to write, of all things, Superman. Yang thus parallels the team’s story with a node of decision in his own life. In this way, the book explains why he is no longer at Bishop O’Dowd, and becomes a bittersweet valedictory to his seventeen-year stretch there (and perhaps a way of prolonging his connection to the school?). There’s a great deal happening in Dragon Hoops, then—the book’s seemingly straightforward structure conceals yet another gutsy high-wire act. This book is jammed full. Starting from a prologue in which Gene, reticent and awkward, seeks out Dragons coach Lou Richie, the story shuttles between present-day profiles and historical background, while also packing in loads of on-court basketball action. The team’s season, and Gene’s growing relationship with “Coach Lou,” are the spine of the book, but Yang freely intermixes other elements, with special attention to particular Dragons and how their team collectively embodies diversity. Chapters depicting important games alternate with chapters devoted to key players (in this sense, the book’s structure is very deliberate). Yang uses the players’ backstories both to celebrate basketball as an inclusive and egalitarian sport but also to point out various problems, notably racism and sexism, in the history and culture of the game. One chapter is devoted to a pair of siblings, Oderah, star of O’Dowd’s championship women’s basketball team, and her younger brother, Arinze, now part of the men’s varsity squad; the two are constant rivals, yet fiercely loyal to each other. Another chapter profiles Qianjun (“Alex”) Zhao, a Chinese exchange student on the Dragons’ team. Another focuses on Jeevin Sandhu, a Punjabi student of the Sikh faith—and here Yang focuses on the challenges of assimilation, while also providing, in effect, a brief introduction to Sikhism. There’s more. Dragon Hoops depicts James Naismith, who invented basketball in 1891; Marques Haynes and his fellow Harlem Globetrotters, who helped integrate the game; Senda Berenson, who launched women’s basketball; Yao Ming, the first star of Chinese basketball to thrive in the NBA; and other notables in the game’s history. Yang smartly interweaves present and past: the chapter on Jeevin also recounts the rise of Catholic schooling and the career of early NBA star George Mikan, a Croatian American player from a Catholic seminary; Yang then acknowledges that Jeevin, as a Sikh, is an outlier in Bishop O’Dowd’s Catholic culture (a scene of Jeevin reciting the Mul Mantar, a Sikh prayer, complements other scenes of praying in the book). Similarly, the chapter on Oderah and Arinzes weaves in Berenson’s story and the rise of the women’s game, including a historic dunk by pioneering college player Georgeann Wells. You can feel Yang matching up elements from past and present to build a tight, cohesive book. Visually, Dragon Hoops is likewise purposeful and designing. Breathless scenes of action on the court, sometimes parsed down to the split second, recall the sort of intense basketball manga popularized by Takehiko Inoue (Slam Dunk, Buzzer Beater, Real). These scenes attain an energy and forcefulness that exceed Yang’s previous work (even the martial violence of Boxers & Saints). There are sequences that fairly set my pulse racing. What makes these explosions of action thrilling is the way the book as a whole carefully measures out its storytelling, and uses the very controlled braiding of repeated imagery to reinforce its themes. Yang recycles and repurposes the same signal images over and over, to point up thematic parallels between past and present, among the different players, and between the Dragons’ quest for the championship and his own concern about going “all in on comics” as a career. Dragon Hoops is a library of key images, reworked and re-inflected (indeed, it could take the place of the vaunted Watchmen when it comes to classroom lessons about braiding!). In fact, it’s a brilliant sustained feat of cartooning for the graphic novel form; the book echoes back and forth, as Yang plays the long game. There’s a kind of nervousness, though, behind Yang’s cleverness. Dragon Hoops is an anxious, self-conscious work. Like Spiegelman’s Maus—and a great many other graphic memoirs since—it reveals and worries over its own stratagems. The authorial notes in the book’s back matter frankly discuss Yang’s sourcing and his occasional resort to artistic license. Said notes relate to the main story dialectically and at times critically (reminding me of the disarming notes in several books by Chester Brown). In particular, Yang admits that he has cast his wife Theresa as, essentially, his sounding board and proverbial better half: wise and practical, humorously tolerant of his anxieties, and full of advice and encouragement (or reasonable doubts about his judgment, as the occasion demands). Talking to Theresa becomes a means of registering Gene’s doubts about his own project, and the sometimes choppy ethical waters that the project gets him into. Though Theresa makes an impression, she does not really emerge as a full-blown character (and the same could be said of Theresa and Gene’s children). Yang notes that he took “particular liberty” with her dialogue: “I figured I could because, y’know, we’re married.” His notes are full of revealing asides like these, which invite a closer look at Dragon Hoops as a performance and a made thing, not just an artless recording of real-life events. Yang’s self-reflexive disclosure of his artistic feints happens not only in the back matter but also in the main story. Dig these two successive panels, on either side of a page turn: In particular, Yang depicts himself worrying over a single compromising plot point: a deeply troubling element of real life that threatens his desired “feel-good” story but that he feels he cannot omit. That ethical sore point is seeded about a third of the way into the book, after which Gene frets and frets over it—until a moment about four-fifths in, when Gene, or rather the book, enacts its moment of decision: Readers of Maus may be reminded of Art’s insistence that “reality is too complex for comics"—which Yang echoes here, stating that comics are “essentially lies.” (Spiegelman too sometimes casts his wife, Françoise Mouly, as a sounding board whose dialogue makes his work’s ethical complications clearer.) In the case of Dragon Hoops, this sort of self-reflexive gambit becomes a fundamental plot element, in fact a suspense generator, long before Yang reveals precisely why. We spend a good part of the book wondering what he is hiding, and how he will reveal it (of course, this plot tease makes it obvious that at some point he will). This isn’t a terribly original move—graphic memoirs have been depicting the rigors of their own making since at least Justin Green—but here it feels almost like a forced move, as if Yang was compelled to it by unnerving real-world details that he could not wish away. Anxiety over this point fundamentally shapes the book’s narrative structure. Dragon Hoops, then, perhaps seeks to inoculate itself against criticism. That is, Yang’s self-critical gambits (there are many) may be meant to deflect charges that his expert storytelling massages the truth a bit too much. I’m not sure that such charges would be fair—but I confess I don’t think Dragon Hoops is Yang’s most convincing graphic novel. Whereas American Born Chinese and Boxers & Saints continue to hint at mixed feelings even as they aim for conclusiveness and wholeness, this book wants to feel emphatically resolved. Yang’s trademark ambivalence yields to a sort of boosterism. At times, Dragon Hoops seems to apply the “underdog” template of most sports stories rather uncritically; for example, the book registers some complicated thoughts about sports, coaching, and Catholic education that its final pages don’t so much resolve as hush. Me, I would have liked to see more critical engagement of what it means to turn young athletes into media stars. I would have liked to see more of Coach Lou’s self-questioning. Dragon Hoops is smart and honest enough to acknowledge problems in the culture of sports, but still wants us to cheer at the final buzzer. Maybe it’s an ironic tribute to Yang’s storytelling that, in the end, I wasn’t quite there. In any case, the book’s reigning structural parallel—how the courage and tenacity of the Dragons empowers Yang to go “all in” himself, as an artist—feels a bit rigged alongside the terrible dilemmas depicted in his previous novels. But, man, it's hard to begrudge Yang the effort, because so much good stuff happens along the way. Dragon Hoops captures a culture, community, and season vividly, and is the very definition of what we should want from a major artist: a step in a new direction, and a dare-to-self that plays out in complex ways. No one could accuse Yang of making things easy on himself. And the book has taught me a lot. As my wife Mich and I take our daily break from isolation, walking the quiet neighborhoods around us, waving (distantly) at passers-by, we see a lot of basketball hoops on driveways and in yards. In fact, a couple of days ago, as we walked uphill through another neighborhood, we heard the sounds of shooting hoops before we came upon the sight: a quick dribble, a silence, a thudding backboard, then more of the same. Sure enough: someone was practicing basketball, solo, in a rear driveway, just barely visible above a tall gate. I had this book on my mind, and had to smile.

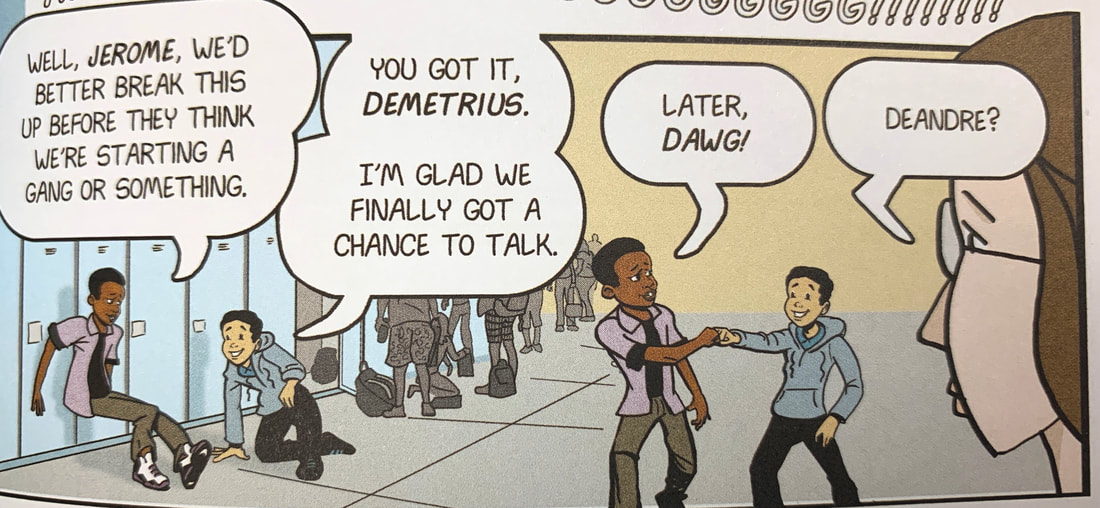

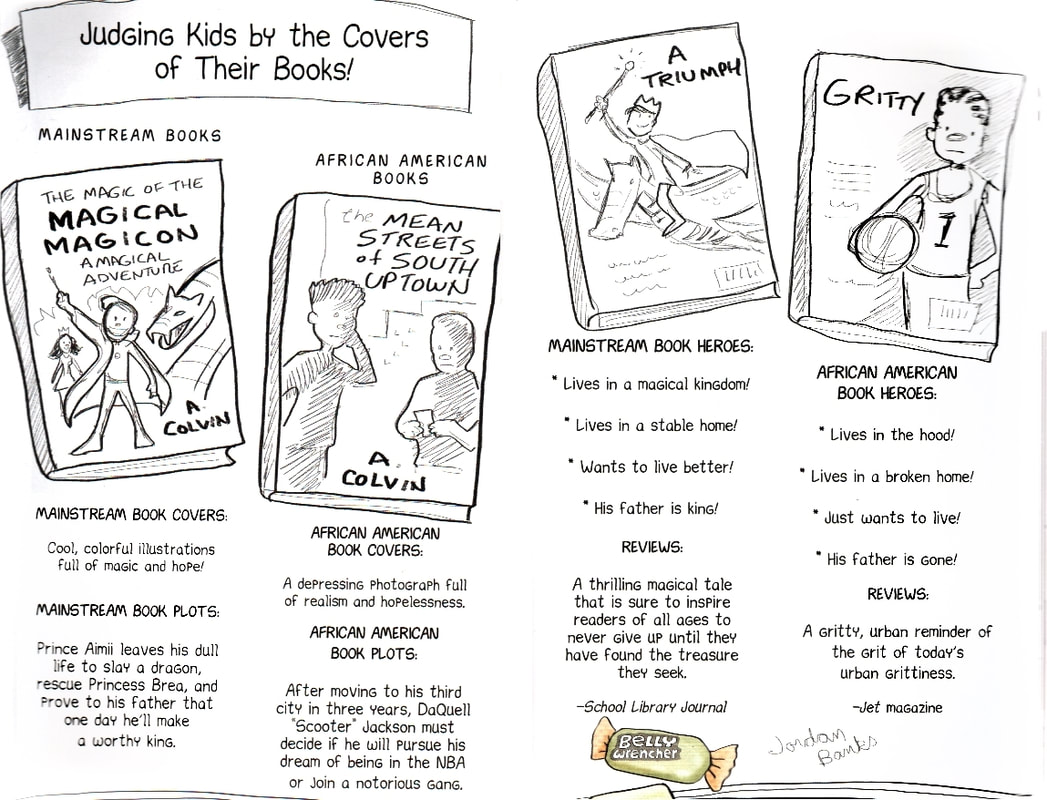

New Kid. By Jerry Craft. Color by Jim Callahan. Harper. ISBN 978-0062691194 (softcover), $12.99; ISBN 978-0062691200 (hardcover), $21.99. 256 pages. A month ago, Jerry Craft’s graphic novel New Kid became the first comic to win the coveted Newbery Medal for children’s literature. I came to New Kid late, and KinderComics readers may remember that I did not include it among my faves of 2019. I wish I had. I confess I put off reading New Kid because I did not love its graphic style, which struck me as cobbled together digitally, with elements seemingly cloned, rescaled, and reused across its pages. At first the work looked patchy to me, compositionally choppy, and too tech-dependent for my tastes. I didn’t see the visual flow or elegance of design that I tend to crave. So, I was closed-mind about this one, I have to say. (This would not be the first time my aesthetic preferences blocked me from recognizing good work. For instance, I recently read Maggie Thrash’s fine comics memoir Honor Girl, done in a seemingly naive watercolor style, and realized that I had been avoiding that one also. I had sold it short.) New Kid deserves better from me. It’s an excellent school story, not only smartly written but visually clever and insinuating throughout. Craft, with exceeding sharpness, depicts African American scholarship boy Jordan Banks and his private school mates at awkward intersections of race, class, and gender. Indeed New Kid, with miraculously high spirits, examines the effects of racism and classism without ever actually breathing those words. Craft is astute and at times can be blunt, but is also endlessly subtle; his touch is marvelously light, yet telling. New Kid manages to be hopeful and often funny, even while acknowledging racism as both systemic feature and stubborn habit. The story of one school year, New Kid gently critiques the class aspirations of private school parents, the casual racist carelessness of teachers, and the blunders of overcompensatory liberal tone-deafness, all while painting Jordan and his fellow students as canny survivors. The book abounds with sly, knowing recognitions, unexplained but pointed, including many gags that show Jordan trying to deal quietly with racial and class-based awkwardness. A middle-class Black boy in a (to him) new school that defines the very notion of privilege, Jordan is alive to the implications of every social move. Craft’s approach is at once realistic, worldly, amused, jaded even, and yet guardedly optimistic; he is properly impatient with ingrained prejudice, yet fatalistically aware that, well, young people have to get on in this broken world. New Kid humorously acknowledges the ways young people of color are too often seen, or rather mis-recognized, and fences smartly with the usual stereotypes about young urban Blackness. The school kids mostly come out well here: they see and deal with social inequality and the willed blindness of adults while upholding their sense of humor and camaraderie. Running gags and droll in-jokes are everywhere: a kind of code and coping mechanism among the kids. For example, Jordan and his classmate Drew call each other mistaken names throughout, mimicking the cluelessness of their white teacher who cannot distinguish one Black student from another. The jokes in New Kid are not just funny, but insightful—as are the young people who tell them. One of the best things in New Kid is a self-reflexive spoof of children’s and young adult publishing that mocks the narrowness of Black depictions in the field. This spread made me laugh out loud (please forgive my crummy scan): If, as Philip Nel argues in Was the Cat in the Hat Black?, the cordoning off of genres marks a de facto line of segregation (Genre Is the New Jim Crow, in Nel’s phrasing), then Craft gets this exactly, and takes the whole publishing field to task. Indeed, the sight of a “gritty” novel for Black teen readers becomes a repeated joke in New Kid, one that stings with its insight but is also downright hilarious. Bravo! This is a supremely wise and charming book that jousts with, and defeats, a thousand cliches.

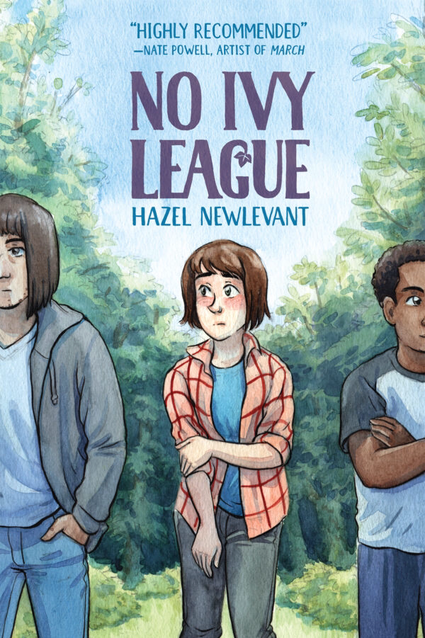

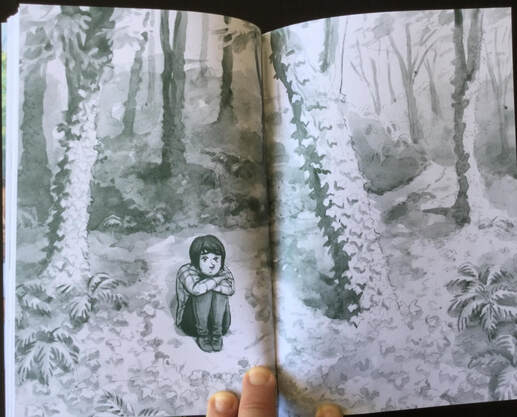

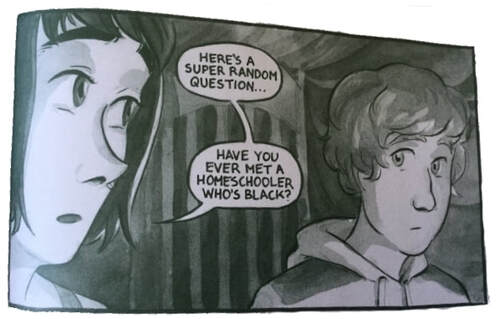

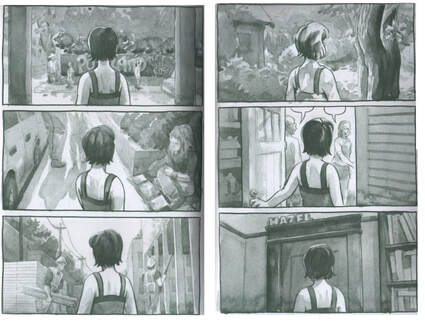

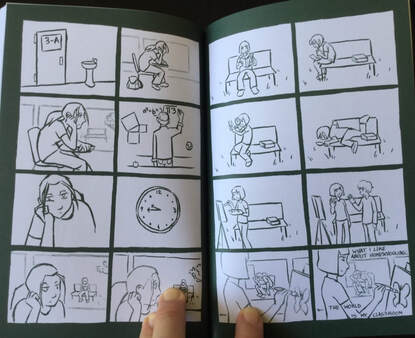

No Ivy League. By Hazel Newlevant. Roar/Lion Forge, 2019. ISBN 978-1549303050 (softcover), $14.99. 216 pages. No Ivy League, a memoir of adolescence, recounts a transformative summer in the life of author Hazel Newlevant. That summer, they (Hazel) took a first tentative step out of the cocoon of their homeschooled upbringing by joining a teenaged work crew clearing ivy from the trees of Portland, Oregon’s Forest Park. That crew consisted of high school students, diverse in class and ethnicity—a sharp contrast to Hazel’s sheltered, all-white life. (Note: I refer to Hazel the character by Newlevant’s gender pronouns they/them/their, though the book’s treatment of that issue is ambiguous: Hazel is addressed by her peers as “girl” or chica, but is seldom if ever referred to by pronoun.) Essentially, No Ivy League is the story of a challenging summer job. It depicts Hazel as not quite up to the challenge: a well-intentioned yet privileged and obtuse kid, painfully self-conscious, whose homeschooling has left them unprepared for the social and ethical challenges of getting along in a varied group. This can be inferred even from the book’s cover (above), which epitomizes Newlevant’s way of getting inside their teenage self and showing their social awkwardness and anxious aloneness. There are lots of fretful images of Hazel like this within the book. I’ve been looking forward to No Ivy League since Newlevant previewed the book at the 2018 Comics Studies Society conference (they were a keynote speaker there, in conversation with fellow artist Whit Taylor). It was a pleasure to meet them and hear them reflect on their creative process. Visually, the end result does not disappoint: the book boasts sharp, emotionally readable cartooning and atmospheric settings, built out of layered watercolor washes and selective touches of brush-inking (the book’s back matter demonstrates Newlevant’s process). The drawings are made of light and shade. Newlevant makes many smart aesthetic choices, not least the pages’ rich green palette, which, fittingly, often shades into deep forest hues. The overall look conjures the green spaces of Forest Park. This is a lovely, well-designed book. No Ivy League’s narrative, though, doesn’t quite convince me. It has a point to make; certain things (telegraphed in the jacket copy and in Newlevant’s own notes) are meant to come through clearly. Hazel is meant to see their own upbringing in a newly critical light, as they realize their white privilege and class privilege. In particular, they are meant to regret reporting a coworker of color for sexual harassment (one humiliating, profane remark), since their words cost that coworker his job. Guilt leads Hazel to examine critically the prevailing whiteness of home-school culture, and to research the history of integration busing in Oregon, which leads to a dismaying realization about their parents’ own motives for home-schooling them. In effect, all this teaches Hazel to recognize the privilege that separates them from their coworkers. But these revelations have a second-hand quality that doesn’t feel earned. This is not for want of trying on Newlevant’s part; individual scenes are nuanced, and Newlevant does not shy away from problems. But the book’s form, as a literal memoir, does not allow for a complex treatment of the diverse work crew in which Hazel finds themself. The storytelling remains too intimately tied to Hazel’s anxieties and desires, and never builds its other characters beyond hints. Those hints are good—they suggest what Newlevant could do with a freer novelistic development of the book's themes—but everything remains keyed to the growth of Hazel’s consciousness, so that, ironically, the book’s form ends up mirroring the self-absorption that Newlevant so clearly intends to criticize. The story’s resolution, which affirms community across ethnic and class lines, feels like a lunge for closure that isn’t warranted, based on what the story gives. In short, No Ivy League feels a bit signpost-y to me, i.e. forced. Still, there are terrific things in this book. For one thing, there’s a lot of smart dialogue and physical blocking. Newlevant well captures the awkwardness of Hazel’s social moves, their blundering, unsure way of making connections, and (again) their sense of isolation. For another, Newlevant does intriguing things with design, rhythm, and the braiding of details. A wordless two-page sequence captures Hazel’s alienation from their own once-comfortable surroundings: Hazel’s animated video extolling the advantages of homeschooling (their submission to a contest among home-school students) comes up twice, and the second time we see Hazel watching it with a more critical eye, their own expressions superimposed over the video’s images: On the other hand, the book includes some narrative feints that don’t come to much, such as a subplot about Hazel’s relationships with their boyfriend and with an older supervisor (on whom they have a crush). That narrative dogleg doesn’t seem to lead anywhere—though, to be fair, one could argue that that’s the point (perhaps Hazel puts aside romance in favor of a greater self-discovery?). To me, it felt like a dangling, untied thread. Overall, I was left feeling that Newlevant’s narrative reach had exceeded their grasp. Given a conclusion that feels willed but not organically attained, I came away with, mainly, a nagging desire to learn more about what I can only call the book’s “supporting cast” (an inadvertent testimony, perhaps, to Newlevant’s storytelling potential). No Ivy League, I think, wants a form better-suited to conveying its cocoon-busting message. That said, the book is visually elegant and transporting. Newlevant is a gifted cartoonist with a keen sense of place and mood. They are also, my criticisms aside, an ambitious writer who merits following. I urge my readers to seek out No Ivy League and give it their own considered reading.

A guest post by Joe Sutliff SandersMy colleague Dr. Joe Sutliff Sanders has kindly agreed to follow up my initial post in a series that I'm calling our Teaching Roundtable. This series stems from my preparations for teaching, in Fall 2018, a course called Comics, Childhood, and Children’s Comics, and my thoughts about the challenges of designing such a course. Thanks, Joe! - Charles Hatfield The best teaching that I have ever done has always been set up just beyond the edge of what I actually understand. You’ll hardly be surprised to learn, then, that I am in love with the idea of this blog. Charles does know a thing or two about comics, but he’s starting this blog conversation about the course not with what he knows, but with where he knows he’s going to have problems. It’s sick; it’s beautiful. I love it. As fate would have it, I happen to be in a very good situation to think about what can go wrong teaching childhood and comics. I’ve just relocated to Cambridge, where the teaching is very, very different from what I’ve done (and experienced) in every other classroom. The number one problem that I keep experiencing is that when the nature of the course wants us to lecture about the center, the books that Have To Be Known, then that nature is insistently nudging us away from the rich work done by people on the margins. For me, this urge toward the center is constant because at Cambridge we teach in a model that might best be understood as serial guest lecturing. Students have a different instructor almost every week, and once I have taught my subject, it might well never come up again for the rest of the term—indeed, the rest of the year. I have about two hours to give the students a fiery introduction to the material that will drive them to go educate themselves about the subject once I’m gone. If I can only ask them to read one book to prepare for my day in front of them, don’t I have to assign them the most canonical, traditional, familiar, central…let’s call it what it is: White…text possible? And Charles isn’t going to find the challenge much easier. Yes, he has the same students for a few months, so with some judicious selection, he can assign both the center and the margin. But there will be times when the nature of the subject seems to insist on safe, familiar choices. For example, while talking about the Comics Code, which was developed by influential White businessmen to protect their interests by playing to 1950s sensibilities of American middle-class propriety, how will he escape a reading list that is White, White, White? The men whose comics sparked the outrage were White; the public intellectual at the center of the debate was White; the men who wrote the Code were White; the books that thrived under the new regime were White. What reading material central to this history will be about anything but Whiteness? Or how about teaching the origins of cartooning? The most common version of the history of comics is populated by White Europeans who had access to the training and venues of publication necessary for a career as a public artist. I’m uncomfortable (to put it mildly) with a module featuring only them, but what are you going to do, not teach the center? These problems arise from comics as a subject matter, but there’s another problem rooted even more deeply in the specific aspect of contexts that Charles has chosen. The title of the course pinpoints "childhood," yes? Childhood’s close association with innocence, which is itself associated with Whiteness (if you don’t believe me, ask Robin Bernstein), is going to make straying from the center even more problematic. Here, as above, the enemy he faces is the nature of the subject. But there is another potential enemy. If—or, knowing Charles, when is the more appropriate word—he edges the reading list and classroom conversation away from innocence, will his students still recognize what they are reading as children’s comics? It’s not just the institution and the subject matter that insist on staying safely in the zone of the canonical…it’s frequently the students as well. So will his students resist when the reading list includes perspectives that don’t fit with the general notion of lily-White childhood? Charles asked me here only to point out his looming problems, but I feel some tiny obligation to offer some possible solutions, too. For example, when teaching the origins of comics, it might do to teach a competing theory, namely the theory that what we call comics today owes a debt to thirteenth-century Japanese art. Frankly, I don’t find that theory convincing (though I think that the influence of another Japanese art form, kamishibai, on contemporary comics has potential), but so what? Our job isn’t to teach proved, finished intellectual ideas, but to help train students to struggle with ideas on their own, and giving them a theory that mostly works will put them in the position of critiquing (or improving) it themselves. Another idea: rather than letting innocence and Whiteness be default categories, rather than letting them force us to defend any deviation from their norms, make them subjects. This is the brilliant move that feminists made with the invention of "masculinity studies": take the thing that has rendered itself invisible and make it the object of study. I’m still concerned that we’ll wind up with all-White reading lists, but this strategy allows us to observe the center without taking the center for granted. Wow, that was fun! Who knew that pointing out other people’s problems and then walking away whistling would be so liberating? Thanks for the invitation, Charles, and I can’t wait to read the posts from the upcoming comics scholars. (Up next: Dr. Gwen Athene Tarbox!) Joe Sutliff Sanders is Lecturer in the Faculty of Education at the University of Cambridge. He is the editor of The Comics of Hergé: When the Lines Are Not So Clear (2016) and the co-editor, with Michelle Ann Abate, of Good Grief! Children and Comics (2016). With Charles, he gave the keynote address on comics and picture books at the annual Children’s Literature Association conference in 2016. His most recent book is A Literature of Questions: Nonfiction for the Critical Child (2018). |

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed