|

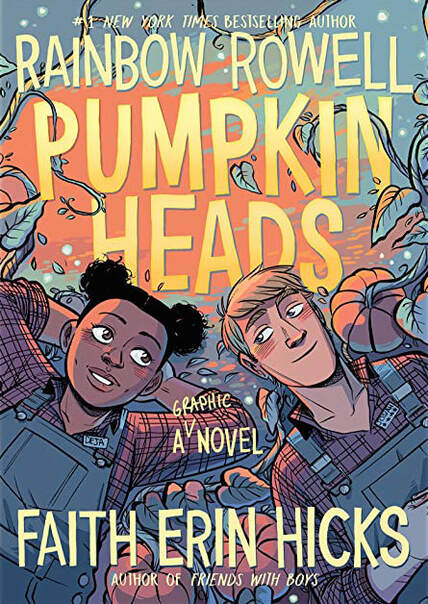

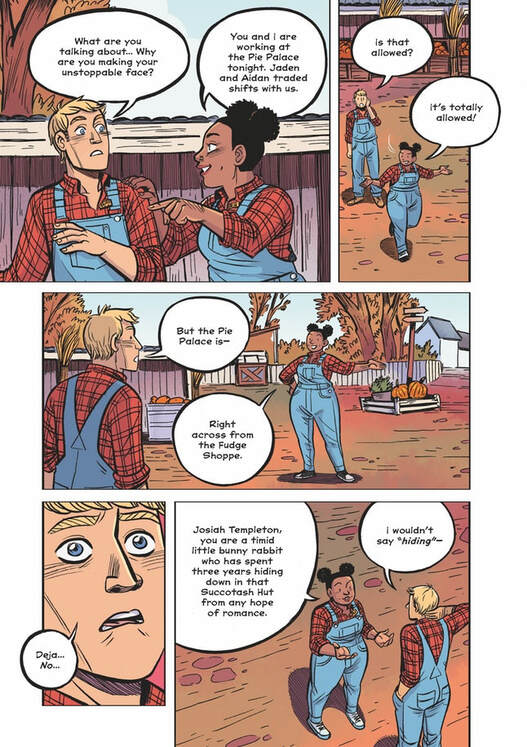

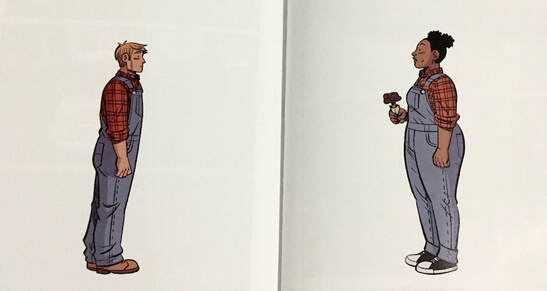

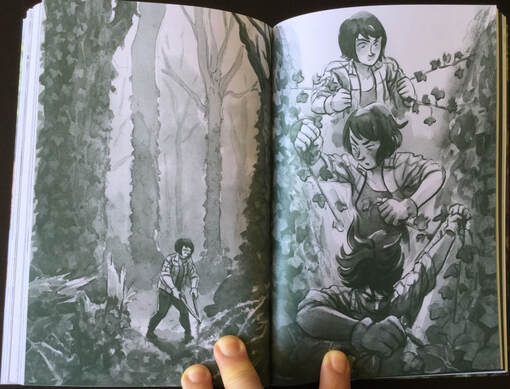

Pumpkinheads. By Rainbow Rowell and Faith Erin Hicks. Color by Sarah Stern. First Second. ISBN 978-1626721623 (softcover), $17.99; ISBN 978-1250312853 (hardcover), $24.99. 224 pages. Pumpkinheads is a breeze of a graphic novel: a busy, boisterous story of roughly six hours shared by two high school seniors one Halloween night. It follows Deja and Josie (Josiah), two seasonal workers at a Midwestern pumpkin patch (replete with corn maze, hayrides, petting zoo, etc.). Deja and Josie are wistfully anticipating graduation and goodbyes, but insist on sharing this “last” Halloween together, which turns out to be a bit of a crazy night. What starts with a gesture of farewell ends by hinting at the possibility of shared times to come. Deja, who seems to have dated every other girl and boy at the patch, comes across as the more socially conscious and proactive of the two, while Josie, a “most valuable” employee and pumpkin geek, is shy, passive, and obtuse. Deja aims to help Josie talk to another patch worker, a girl he’s been mooning over fecklessly for the past three years—this may be his last chance to break out of his shell and strike up a relationship with her. Yet finding that girl in the big sprawl of the patch proves a challenge, as the two run into one colorful mishap after another. Outwardly, the suspense has to do with getting Josie to that girl, but what really matters is the relationship right in front of us: Josie and Deja. The book hints and hints at the special nature of their friendship—will they recognize it before the night is through? Deja and Josie are complementary opposites, but both love, in an unselfconsciously nerdy way, the corniness of the pumpkin patch and its attractions. Where they differ is in their attitudes toward sociability. Josie is the type to wait for good things to come to him — he doesn’t know how to initiate a relationship — but Deja tells him that he must make choices and act on them if he is to get anywhere with anyone. The plot consists mainly of their walking, talking, and solving minor crises at the patch: together they run into various of Deja’s “exes,” navigate the fudge shoppe, s’mores pit, and corn maze, and reunite a lost child with her mom. There’s a lot of funny, rowdy action, but, again, what matters is their dialogue, which telegraphs an unacknowledged depth of feeling between the two. We readers perhaps get to know them better than they know themselves. Scriptwriter Rainbow Rowell captures the offhand, familiar quality of friendly banter; you can believe that Deja and Josie have known each other for a long time. Cartoonist Faith Erin Hicks supplies (as the book’s back matter makes clear) the layout and rhythms, pacing and punctuating the action with wordless panels full of significant glances and sly, well-observed business. Theirs is a felicitous collaboration, intently focused on the two leads, their comical backdrop, and their dawning self-awareness. The results are seamless and fun to read. Pumpkinheads is perhaps thematically slight, reflecting Rowell’s stated desire to do something “light and joyful.” It may be utopian; certainly it's idyllic and matter-of-factly progressive. Tonally, the book echoes many middle-grade stories that anticipate high school without the critical awareness of social power and inequity typical of YA fiction. Set in an idealized Midwest, it skirts questions of racism and homophobia (Deja, a queer young woman of color, is treated as wholly accepted and socially unremarkable). Implicitly, the book promotes body positivity: Deja is (as Rowell describes her) chubby, and one scene deals subtly with fat-shaming, but her beauty and vivacity are never in doubt. Josie, in contrast, is the very image of cornfed white Midwestern handsomeness. The supporting cast is discreetly diverse (though we learn little about them). Mainly, this is a charming story about discovering the depth of a relationship, equal parts ebullient comedy and quiet romance. Rowell and Hicks understand and love their characters, and Hicks draws their interplay with a keen eye for pauses, insinuations, and unspoken currents of feeling. In the end, Pumpkinheads is succinct, pleasant, and remarkably well crafted: a model middle-grade graphic novel, thematically unexceptional maybe, but sweetly human.

0 Comments

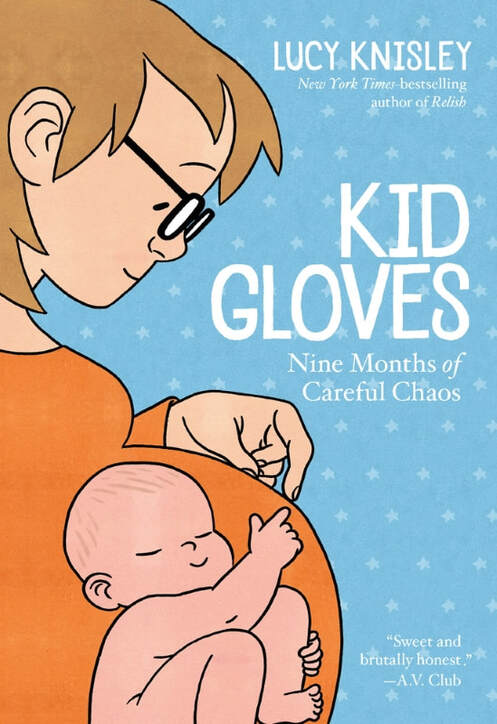

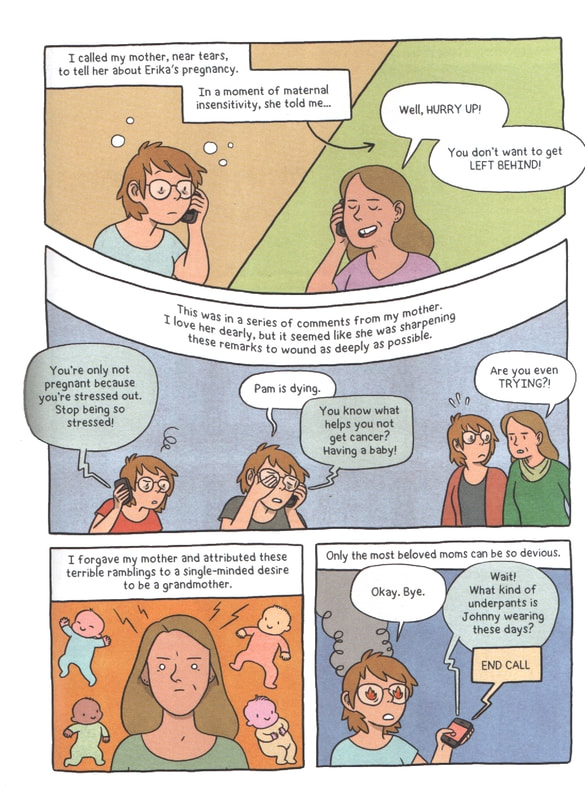

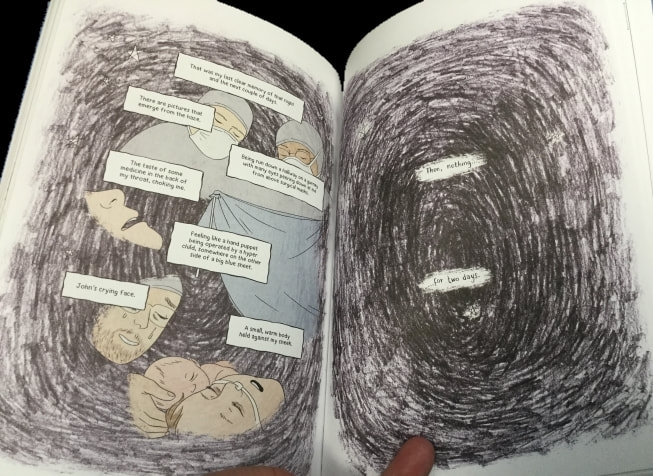

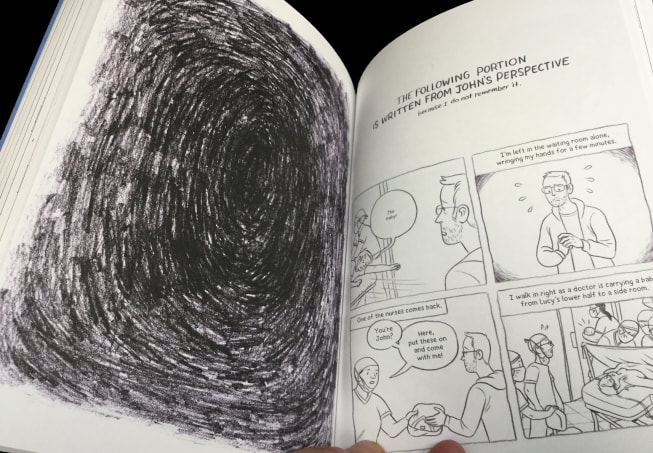

Kid Gloves: Nine Months of Careful Chaos. By Lucy Knisley. First Second. ISBN 978-1626728080 (softcover), $19.99. 256 pages. Kid Gloves tells of author Lucy Knisley’s pregnancies and miscarriages, and finally the birth of her and her husband’s child. Blending memoir, childbirth education, and self-help, the book also offers, at times, sharp criticism of both sexist birthing institutions and natural childbirth truisms. Between chapters of personal narrative, Knisley inserts brief interchapters devoted to “pregnancy research”—actually, a mix of contextualizing details and Knisley’s pointed editorializing: often humorous, sometimes exasperated. These interchapters are didactic but droll, and not impersonal; they resonate with Knisley’s own story. The larger personal narrative takes us through Knisley’s miscarriages and resulting depression, then on through the conception, bearing, and delivery of her child—itself a traumatic, life-threatening event (due to eclampsia and seizure). A lot of scary stuff is replayed in this story, but also a great deal of joy and good humor. Knisley comes across as a friendly but not uncritical guide to the vagaries of pregnancy, opinionated, blunt, and confidential. She relays her story from a safe retrospective distance: her introduction shows Lucy and the baby, weeks after delivery, doing okay, and the narrative captions reassuringly carry us along. That is, the story is recounted in hindsight, rather than rawly dramatized. All this is delivered (sorry!) via Knisley’s reliably excellent, toothsome cartooning, dynamic yet readable layouts, and beautiful colors—signs of her offhand mastery of the craft. Wow, can she make comics. I admit I approached Kid Gloves a tad nervously, unsure of whether Knisley’s writing would be equal to her subject. My first experience of her work, her memoir Relish (2013), had frustrated me with what I took to be its unexamined entitlement, skirting of emotional complexity, and preference for glib affirmation over fierce self-examination. Knisley does not do raw confessionalism or self-damning underground memoir. While her work does take on hard things, she tends to adopt a position of earned confidence and matter-of-factness (again, self-help is a useful point of reference). Her rhetorical construction of self is not the fractured self of Green or Kominsky-Crumb, nor the compulsively self-questioning, reflexive self of Spiegelman or Bechdel (though she does indulge here in comically grotesque caricatures of her changing body and its trials). Knisley the narrator seems secure even when Kid Gloves depicts the depths of depression or the harrowing trials of illness and emergency. It is a reassuring sort of memoir that offers a sane perspective-taking rather than an unsettled, open-ended questioning (in this, it reminds me of what Ellen Forney has done in her memoirs of bipolarity). Indeed, at times Kid Gloves skates over complex things much as Relish did. For example, in a sequence that my wife Michele called to my attention, Knisley recalls the aftereffects of one of her miscarriages, and what she characterizes as her mother’s insensitive response: You might think that this characterization would lead to a considered treatment of her mother throughout the remainder of the book, one that would balance daughterly love and forgiveness against frustration and critique. But Knisley accepts this tension between mother and daughter as an unresolvable, and moves on, not revisiting these hard feelings but tucking them away. (You won’t find here, for example, the extended, ambivalent treatment of parent-child relationships that you’ll see in Thi Bui’s The Best We Could Do.) I worried that this key moment, which comes early in the text, would cancel Knisley’s piercing depictions of depression, that she would paper over complexities in the quest for a feel-good equanimity such as we so often see in popular memoir and self-help books. Knisley, however, proved me wrong. Her narrative goes on to address challenging issues, including her and her husband’s anxieties, her triggers and preoccupations, the wrenching bodily demands of pregnancy, and her tense relationship with childbirthing dogma. The actual birth of her son, accomplished by cesarean and blurred out by medication, brings an explosive change to Knisley’s pages, suggesting lingering trauma and loss. Further, when her own life hangs in the balance, Knisley switches focalization to her husband, with drastic changes in her technique. There are moments when her always decorous, conspicuously well-designed pages become unsettled and the delivery of her story becomes most piercing. The book’s climax moved me beyond my expectations. Michele read Kid Gloves before I did, and told me frankly that the book raised up some difficult memories for her. This was perhaps another reason why I approached the book with a bit of dread. It’s true that reading it brought up some of my own memories of how Michele and I wrestled with medicalized childbirth and its outcomes. Frankly, I was surprised by how much Knisley criticizes natural childbirth rhetoric and embraces what she calls “hospital-based interventions” (even as she recounts what were arguably cases of medical malpractice). Kid Gloves, it's fair to say, takes a jaded view of the power struggles between obstetrics and traditional midwifery. These notes brought up memories of our own childbirthing experience; they also got me to question Knisley's wisdom. At times, the old feelings of impatience regarding her writing came back to me. There was a whiff of unexamined entitlement about Knisley's weighing of women’s “choices” in childbirth (“as long as everyone’s healthy”), and behind her settled self-presentation I sense a certain hardheadedness. But, still, Kid Gloves is a forthcoming and bracing story, one that will surely prove inspiring to many readers going through the childbirthing experience or seeking to put it into perspective afterward. By book’s end, I felt grateful for the ride. In sum, Kid Gloves uses the all-at-onceness and richness of the comics page to tell a story that is at once personal, instructive, and political. I don’t quite love it the way I love comics that tell of childbearing from a rawer, less protected place (check out Lauren Weinstein’s superb Mother’s Walk), and I note that Knisley continues to walk the knife’s edge between personal exploration and tidy, marketable endings. But Kid Gloves marks a step forward for her as a writer, and I recommend it.

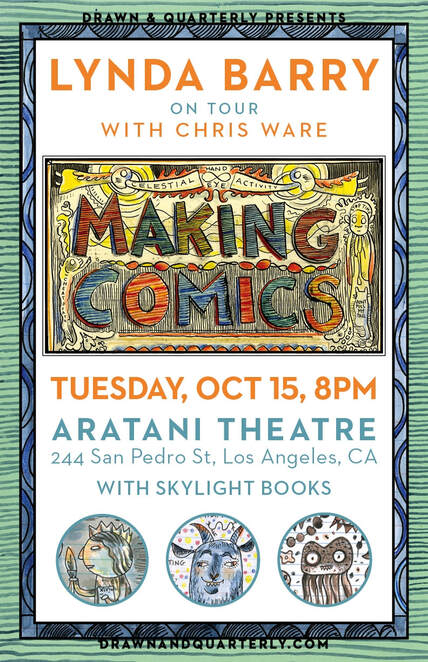

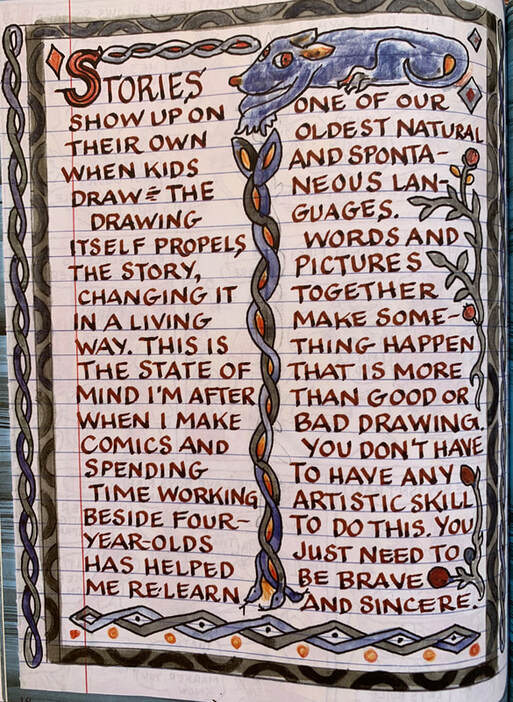

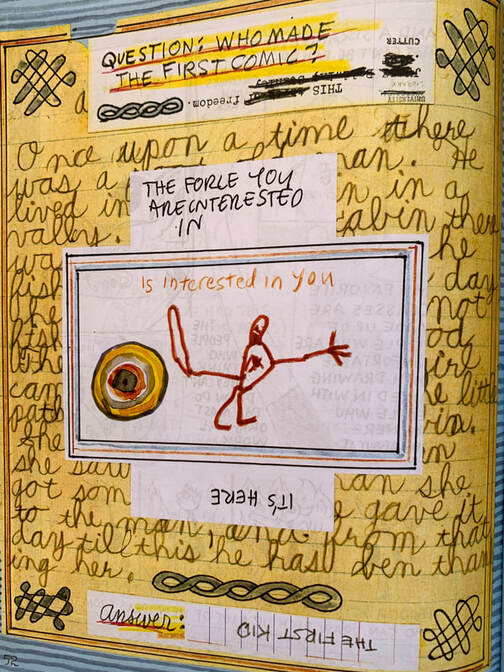

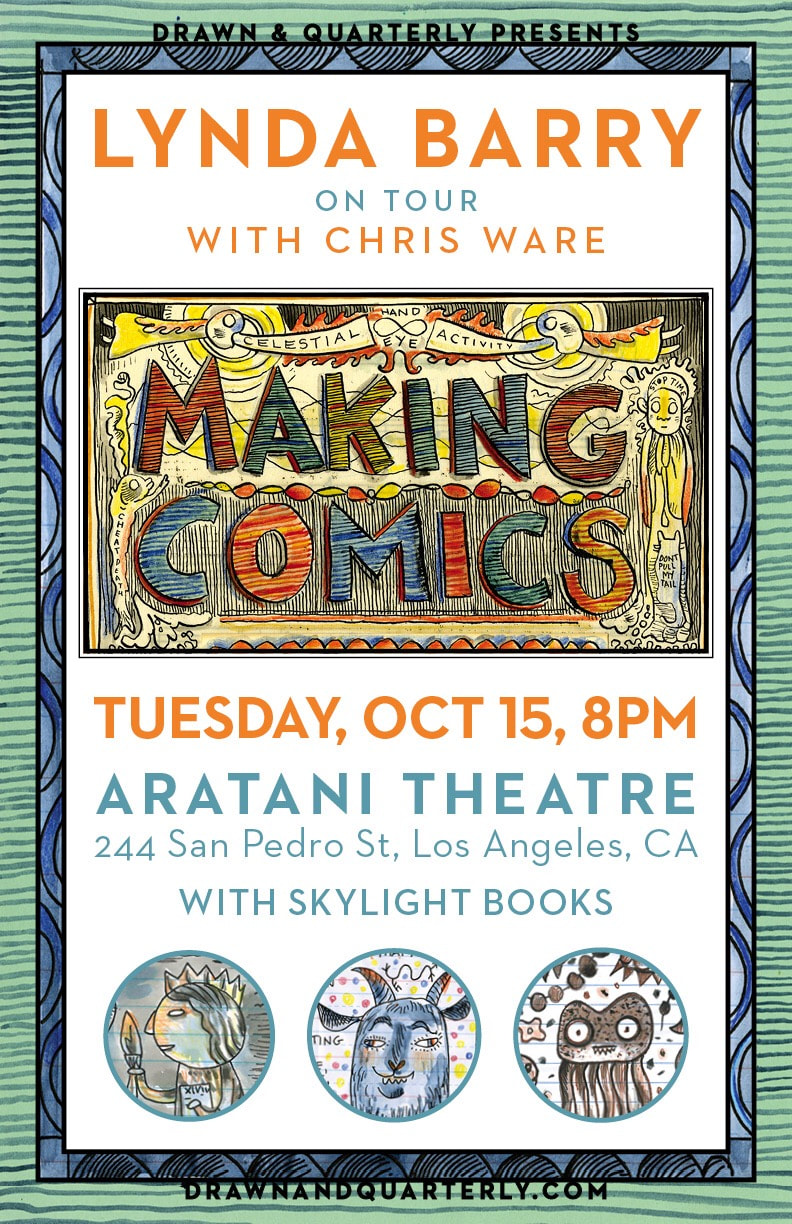

Tuesday night’s conversation between Lynda Barry and Chris Ware (at the Aratani Theater in downtown Los Angeles, organized by Skylight Books) touched on childhood again and again. Both artists shared pictures or artifacts from their childhoods and recounted formative childhood experiences: Ware recalled a life-changing friendship he had as a young boy with another introverted, comics-loving schoolboy, memories of which continue to fuel his work (particularly his new graphic novel, Rusty Brown). Barry expressed her delight at working with four-year-old artists as well as university students, and evoked her girlhood experience of watching a troubled young uncle draw obsessively (a story movingly told in her new book, Making Comics). Both artists stressed honesty and spontaneity over scripting or planning, and invoked the unselfconscious narrative drawing of children as an inspiration. Barry, animated, disarming, and often hilarious (as ever), showed photos and videos of young kids drawing and learning, her comments suggesting an almost Wordsworthian romantic regard for children’s untrammeled creativity (though mixed with a matter-of-fact acceptance of the terrors that kids’ stories so often uncover). Ware, woefully self-deprecating (as usual) but also articulate and funny (as usual), spoke of memory, of reinhabiting remembered spaces and using comics to move through recollected time. It was one hell of a chat. Ware began his comments by recalling how Barry inspired him, early on. He was clearly in awe of Barry and delighted by her irrepressibility. Barry readily drew him (and the audience) out, and into deep conversation. Aesthetically, the two artists would seem an odd match, and frankly I think their works differ fundamentally despite the mutual admiration they projected during their talk, but as a conversational tag team they were delightful. The evening gave me a lot to think about—most of all comics’ debt to memory and the mysteries of narrative drawing. (I only regret that we couldn’t spend hours hanging around afterward, sharing our impressions of the talk with some of the many fans and artists there--a big and enthusiastic crowd. I think there were several people in the audience that I know, but we couldn’t seek them out, as the night was wearing on and we had an early morning to get ready for.) Though Ware’s comments about spontaneity in writing and drawing resonated with Barry’s, I confess I don’t see him working in anything like the same vein. He says that these days he works from page to page, instinctively, without script, but some architectonic notion of form still seems to guide him, and his work remains compulsively crafted in ways that veer far from what Barry celebrates in Making Comics. Indeed, Ware invoked as points of reference, or aspirational guides, such designing literary figures as Joyce and Nabokov, and expressed his admiration for big books that “sprawl” (but that also, I would add, impose global structure through myriad devices). His comments revealed how Rusty Brown is deliberately shaped with an overall sense of form: at one point he likened his new book’s structure to that of a water molecule, or a snowflake forming, and explained how the book’s removable jacket, which charts or anticipates the various narratives contained within, would be complemented by another such jacket when, years from now, he completes the novel’s anticipated second volume (!). So, he is already thinking about design conceits that will contain and contextualize whatever he comes up with. In light of comments like these, I take Ware’s comments about spontaneous invention with the proverbial grain of salt—I don’t think his meticulously crafted surfaces jibe with Barry’s ethos of unlocking creativity through drawing-as-process. I also think that Barry’s theorizing about narrative drawing (“There was a time when drawing and writing were not separated for you”) is really onto something, whereas Ware’s theories about narrative drawing often seem belied by the nature of his own work. For example, when Ware says that the functionality of a drawing matters more than its beauty or polish, I don’t see that borne out by his (often gorgeous, always pristine) pages, and I know many readers fetishize Ware's craft. Yet when Barry says similar things, I see a clear connection between her theory and her pedagogical practice (though I find her pages just as beautiful, in a much different way). In general, I tend to take Ware’s theoretical positions as somewhat at odds with what I see in his work, but Barry, I think, has truly embraced a romantic position about cartooning as demotic and open to all (“You don’t have to have any artistic skill to do this. You just need to be brave and sincere”). The obvious contrast between their respective styles of work, however, did not stop them from finding points to share and admire. Again, Ware seemed grateful to be sharing a stage with Barry, and, I thought, caught some of her energy, while Barry was, in effect, a gracious and delightful host. Despite the manifest differences between their work, I was fascinated to see both of them harking back to childhood as a wellspring of inspiration. They did this in different ways, of course. When asked by an audience member what they would say to their childhood selves if they could go back in time, they had very different answers: Barry said she would assure her younger self that it would all work out fine, that the struggles would definitely turn out to be “worth it." Ware, on the other hand, said he didn’t think he could reassure his younger self because, essentially, his work feeds on sad and anxious memories—that is, reassurance would take away the impetus or subject matter of much of his art. That right there speaks volumes, I think, about their differences in temperament and focus. PS. I’ve been reading Barry’s Making Comics with great interest and hope to review it here. It’s an extraordinary book, one that will influence my teaching going forward (as indeed some of Barry’s previous books already have). This is turning out to be an incredible season for new comics releases!

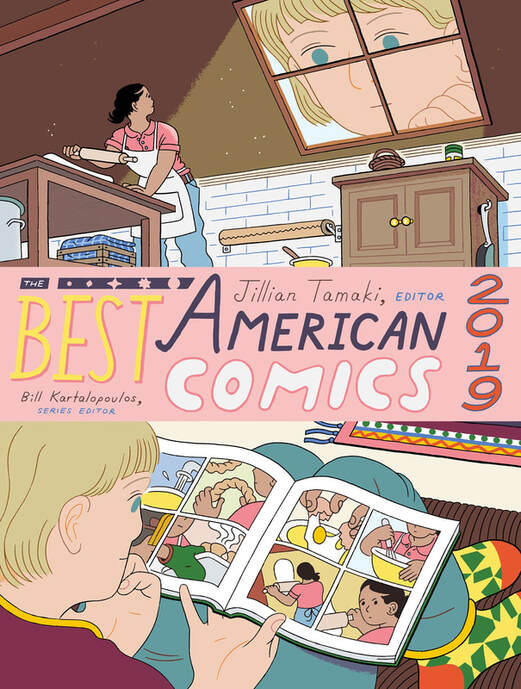

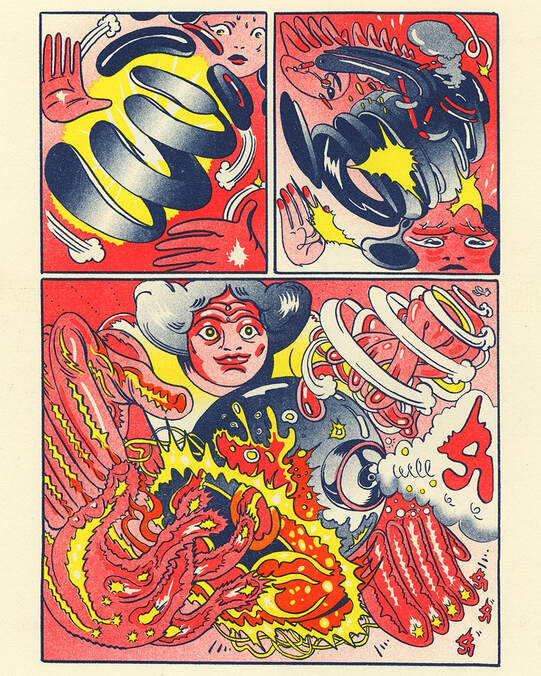

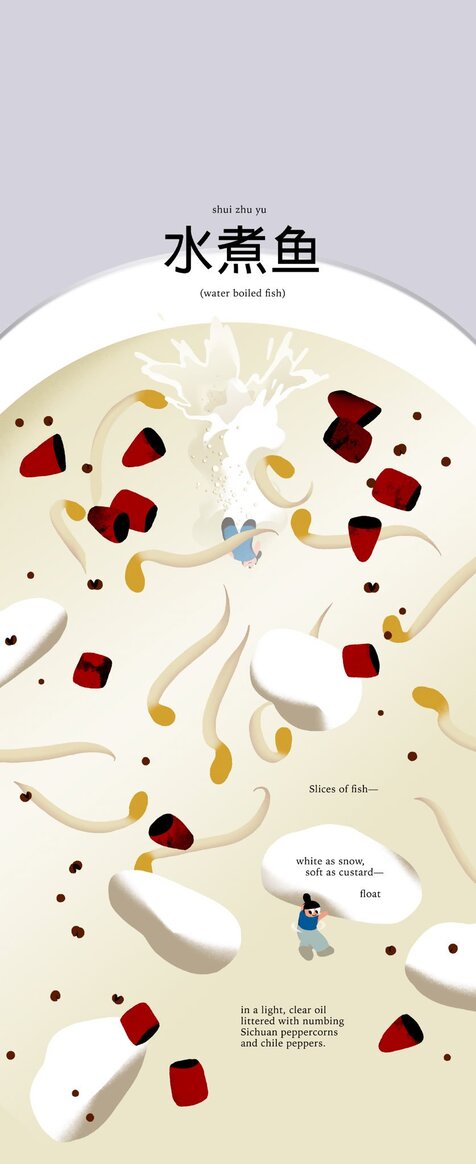

The Best American Comics 2019. Edited and introduced by Jillian Tamaki; series editor Bill Kartalopoulus. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0358067283 (hardcover), $25. 400 pages. Cover by Sophia Foster-Dimino. The Best American Comics series does not aim at young readers, and typically includes frankly adult content. However, its editors have included great writers about childhood, such as Lynda Barry and Neil Gaiman, and great makers of comics for young readers, among them Jeff Smith and this year’s editor, Jillian Tamaki. The series’ remit is to provide “a selection of outstanding North American work” (in this case, published between September 1, 2017, and August 31, 2018). The series, one of many Best American samplers published by HMH, has been published annually since 2006, so fourteen volumes have appeared to date (under three different series editors or teams). I’ve taught two of them (Barry’s 2008 volume was a particular fave that I taught again and again, well after 2008). And I am sure I will be teaching this latest one, 2019, which is a particularly well-curated and beautifully designed edition. You couldn’t ask for a more provocative one-stop sampler of excellent contemporary comics 2019 includes a bounty of distinctive work, and, unusually for this series, few pieces I would have omitted in favor of something else (even those are provocative additions to the mix). Tamaki says that she chose comics “that stuck with me, represented something important about comics in this moment, and exemplified excellence of the craft.” In all, there are twenty-five selections, ranging in length from one page to more than thirty (about half are excerpted from longer works). These were selected from about 120 titles that series editor Bill Kartalopoulus (per the series’ SOP) sent to Tamaki. The resulting table of contents draws from diverse sources, including but not limited to self-published minicomix (for example, John Porcellino’s wonderful King-Cat #78), micro-presses (such as Perfectly Acceptable Press and 2dcloud), online comics (such as by artists Angie Wang and Jed McGowan), established alternative comics publishers (Drawn & Quarterly; Fantagraphics; Koyama Press) and children’s book publishers (Groundwood Books; First Second). Graphic novels, memoirs, floppy comic books, and online magazines (for instance The New Yorker, newyorker.com) are all represented. Interestingly, print anthologies contribute only two selections (or three if you count an excerpt from Remy Boydell and Michelle Perez’s The Pervert, first serialized in the anthology Island). Solo-authored pamphlets and books account for a larger piece of the pie. The works included run the aesthetic range, from rough scrawls to the most elegant of illustrations, from the emphatically handmade (e.g., Lauren Weinstein; Margot Ferrick) to more obviously digital styles (e.g. Angie Wang). Painted, penciled, or inked; mimetically or expressively colored (or uncolored); spare or busy; fictional or nonfictional; straightforwardly narrative or elliptical and nearly abstract—the book embraces, as Tamaki notes, a teeming variety of approaches. I appreciate the way Tamaki and Kartalopoulus have juxtaposed mainstream works for young readers, such as Vera Brosgol’s excellent Be Prepared, with experimental small-press works. I also appreciate the roughly even split of women and men, plus at least one seemingly nonbinary artist, among the contributors. For the record, I had read about one-third of the selections here before, but hadn’t even heard of several (half a dozen creators in the table of contents were new to me). A few were works I had been anxious to read: much talked-about comics like Lale Westvind’s Grip and Connor Willumsen’s Anti-Gone, both of which made many best-of lists in 2018 but which I had trouble finding locally. Some were comics I had snapped with my phone at festivals or shops but had failed to pick up (for example, Laura Lannes’s By Monday I'll Be Floating in the Hudson with the Other Garbage). So, the book has been an education to me. That’s one of the reasons I so look forward to teaching it. The book’s foreword, by Kartalopoulus, and its puckish introduction, written and illustrated by Tamaki, balance seriousness and playfulness, a tightrope act carried on by the rest of the book, which ranges from mischief to poignancy to chilly disturbance—a surplus of strong feelings. High points for me include Westvind’s Grip; Weinstein’s “Being an Artist and a Mother”; McGowan’s posthuman SF fable, Uninhabitable; Sophia Foster-Dimino’s bracing memoir of abortion, “Small Mistakes Make Big Problems” (from Comics for Choice); and Angie Wang’s inventive webcomic about food, memory, and identity, “In Search of Water-Boiled Fish” (originally published on eater.com). The excerpts from bigger books, such as Leslie Stein’s Present, Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina, and Boydell and Perez’s The Pervert, work unusually well in this context. While the book presents some of the usual infelicities caused by reformatting diversely-designed works into the series’ standard size, these are minimal and not too distracting (though Wang’s brilliant scrolling layouts and limited animation cycles are sorely missed in the print version of her piece). In all, Best American Comics 2019 is a terrific volume even by the standards of this series, and, for me, one of the two or three BAC volumes thus far that best lives up to the promise of its title. The team of Tamaki and Kartalopoulus has done excellent work here. Most highly recommended as an exhilarating reminder of what comics, in the here and now, can be. (This book will join Eleanor Davis’s The Hard Tomorrow and Ezra Claytan Daniels and Ben Passmore’s BTTM FDRS as new textbooks in my Comics class next spring.)

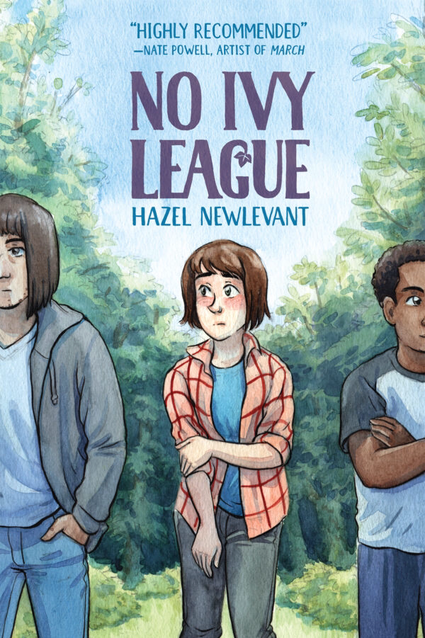

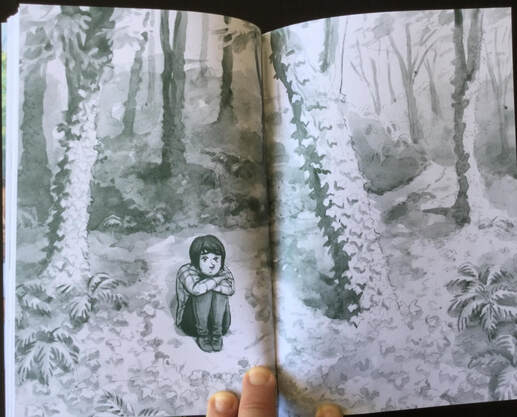

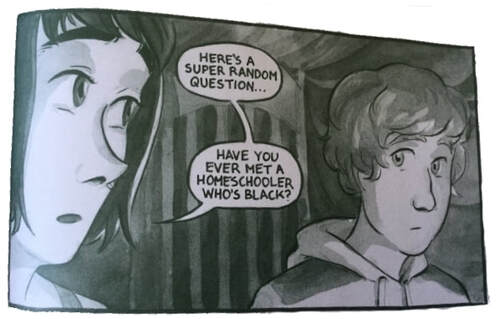

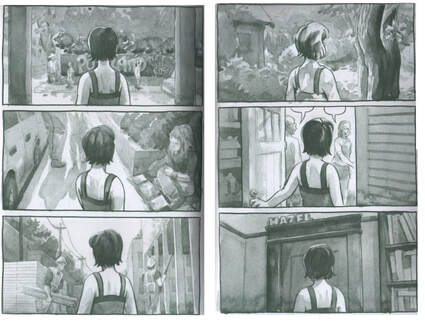

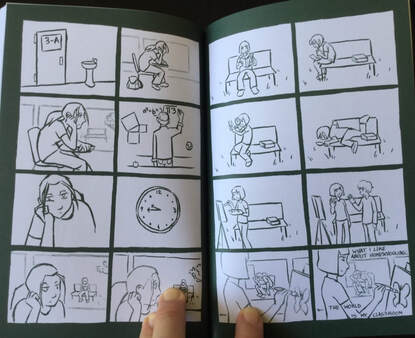

No Ivy League. By Hazel Newlevant. Roar/Lion Forge, 2019. ISBN 978-1549303050 (softcover), $14.99. 216 pages. No Ivy League, a memoir of adolescence, recounts a transformative summer in the life of author Hazel Newlevant. That summer, they (Hazel) took a first tentative step out of the cocoon of their homeschooled upbringing by joining a teenaged work crew clearing ivy from the trees of Portland, Oregon’s Forest Park. That crew consisted of high school students, diverse in class and ethnicity—a sharp contrast to Hazel’s sheltered, all-white life. (Note: I refer to Hazel the character by Newlevant’s gender pronouns they/them/their, though the book’s treatment of that issue is ambiguous: Hazel is addressed by her peers as “girl” or chica, but is seldom if ever referred to by pronoun.) Essentially, No Ivy League is the story of a challenging summer job. It depicts Hazel as not quite up to the challenge: a well-intentioned yet privileged and obtuse kid, painfully self-conscious, whose homeschooling has left them unprepared for the social and ethical challenges of getting along in a varied group. This can be inferred even from the book’s cover (above), which epitomizes Newlevant’s way of getting inside their teenage self and showing their social awkwardness and anxious aloneness. There are lots of fretful images of Hazel like this within the book. I’ve been looking forward to No Ivy League since Newlevant previewed the book at the 2018 Comics Studies Society conference (they were a keynote speaker there, in conversation with fellow artist Whit Taylor). It was a pleasure to meet them and hear them reflect on their creative process. Visually, the end result does not disappoint: the book boasts sharp, emotionally readable cartooning and atmospheric settings, built out of layered watercolor washes and selective touches of brush-inking (the book’s back matter demonstrates Newlevant’s process). The drawings are made of light and shade. Newlevant makes many smart aesthetic choices, not least the pages’ rich green palette, which, fittingly, often shades into deep forest hues. The overall look conjures the green spaces of Forest Park. This is a lovely, well-designed book. No Ivy League’s narrative, though, doesn’t quite convince me. It has a point to make; certain things (telegraphed in the jacket copy and in Newlevant’s own notes) are meant to come through clearly. Hazel is meant to see their own upbringing in a newly critical light, as they realize their white privilege and class privilege. In particular, they are meant to regret reporting a coworker of color for sexual harassment (one humiliating, profane remark), since their words cost that coworker his job. Guilt leads Hazel to examine critically the prevailing whiteness of home-school culture, and to research the history of integration busing in Oregon, which leads to a dismaying realization about their parents’ own motives for home-schooling them. In effect, all this teaches Hazel to recognize the privilege that separates them from their coworkers. But these revelations have a second-hand quality that doesn’t feel earned. This is not for want of trying on Newlevant’s part; individual scenes are nuanced, and Newlevant does not shy away from problems. But the book’s form, as a literal memoir, does not allow for a complex treatment of the diverse work crew in which Hazel finds themself. The storytelling remains too intimately tied to Hazel’s anxieties and desires, and never builds its other characters beyond hints. Those hints are good—they suggest what Newlevant could do with a freer novelistic development of the book's themes—but everything remains keyed to the growth of Hazel’s consciousness, so that, ironically, the book’s form ends up mirroring the self-absorption that Newlevant so clearly intends to criticize. The story’s resolution, which affirms community across ethnic and class lines, feels like a lunge for closure that isn’t warranted, based on what the story gives. In short, No Ivy League feels a bit signpost-y to me, i.e. forced. Still, there are terrific things in this book. For one thing, there’s a lot of smart dialogue and physical blocking. Newlevant well captures the awkwardness of Hazel’s social moves, their blundering, unsure way of making connections, and (again) their sense of isolation. For another, Newlevant does intriguing things with design, rhythm, and the braiding of details. A wordless two-page sequence captures Hazel’s alienation from their own once-comfortable surroundings: Hazel’s animated video extolling the advantages of homeschooling (their submission to a contest among home-school students) comes up twice, and the second time we see Hazel watching it with a more critical eye, their own expressions superimposed over the video’s images: On the other hand, the book includes some narrative feints that don’t come to much, such as a subplot about Hazel’s relationships with their boyfriend and with an older supervisor (on whom they have a crush). That narrative dogleg doesn’t seem to lead anywhere—though, to be fair, one could argue that that’s the point (perhaps Hazel puts aside romance in favor of a greater self-discovery?). To me, it felt like a dangling, untied thread. Overall, I was left feeling that Newlevant’s narrative reach had exceeded their grasp. Given a conclusion that feels willed but not organically attained, I came away with, mainly, a nagging desire to learn more about what I can only call the book’s “supporting cast” (an inadvertent testimony, perhaps, to Newlevant’s storytelling potential). No Ivy League, I think, wants a form better-suited to conveying its cocoon-busting message. That said, the book is visually elegant and transporting. Newlevant is a gifted cartoonist with a keen sense of place and mood. They are also, my criticisms aside, an ambitious writer who merits following. I urge my readers to seek out No Ivy League and give it their own considered reading.

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed