|

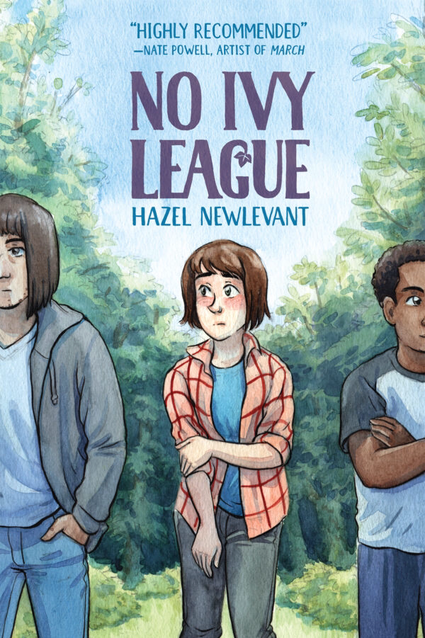

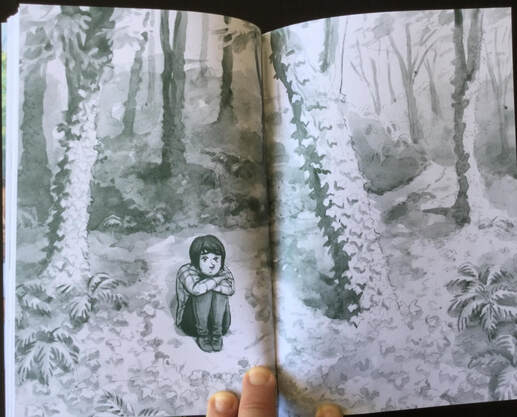

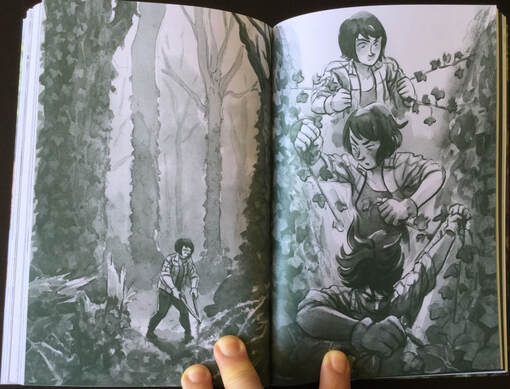

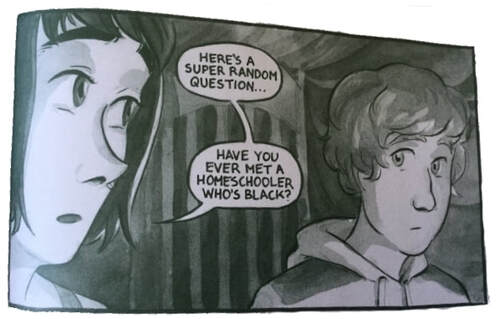

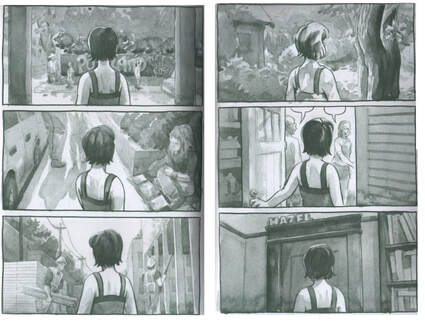

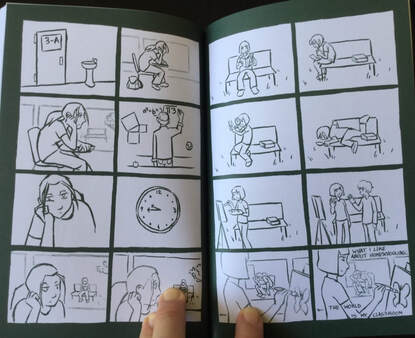

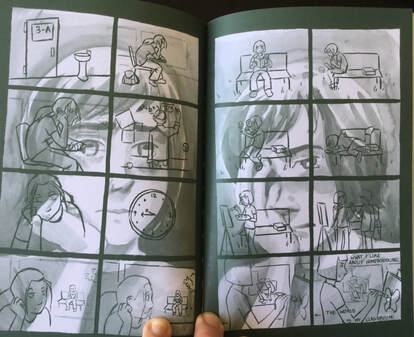

No Ivy League. By Hazel Newlevant. Roar/Lion Forge, 2019. ISBN 978-1549303050 (softcover), $14.99. 216 pages. No Ivy League, a memoir of adolescence, recounts a transformative summer in the life of author Hazel Newlevant. That summer, they (Hazel) took a first tentative step out of the cocoon of their homeschooled upbringing by joining a teenaged work crew clearing ivy from the trees of Portland, Oregon’s Forest Park. That crew consisted of high school students, diverse in class and ethnicity—a sharp contrast to Hazel’s sheltered, all-white life. (Note: I refer to Hazel the character by Newlevant’s gender pronouns they/them/their, though the book’s treatment of that issue is ambiguous: Hazel is addressed by her peers as “girl” or chica, but is seldom if ever referred to by pronoun.) Essentially, No Ivy League is the story of a challenging summer job. It depicts Hazel as not quite up to the challenge: a well-intentioned yet privileged and obtuse kid, painfully self-conscious, whose homeschooling has left them unprepared for the social and ethical challenges of getting along in a varied group. This can be inferred even from the book’s cover (above), which epitomizes Newlevant’s way of getting inside their teenage self and showing their social awkwardness and anxious aloneness. There are lots of fretful images of Hazel like this within the book. I’ve been looking forward to No Ivy League since Newlevant previewed the book at the 2018 Comics Studies Society conference (they were a keynote speaker there, in conversation with fellow artist Whit Taylor). It was a pleasure to meet them and hear them reflect on their creative process. Visually, the end result does not disappoint: the book boasts sharp, emotionally readable cartooning and atmospheric settings, built out of layered watercolor washes and selective touches of brush-inking (the book’s back matter demonstrates Newlevant’s process). The drawings are made of light and shade. Newlevant makes many smart aesthetic choices, not least the pages’ rich green palette, which, fittingly, often shades into deep forest hues. The overall look conjures the green spaces of Forest Park. This is a lovely, well-designed book. No Ivy League’s narrative, though, doesn’t quite convince me. It has a point to make; certain things (telegraphed in the jacket copy and in Newlevant’s own notes) are meant to come through clearly. Hazel is meant to see their own upbringing in a newly critical light, as they realize their white privilege and class privilege. In particular, they are meant to regret reporting a coworker of color for sexual harassment (one humiliating, profane remark), since their words cost that coworker his job. Guilt leads Hazel to examine critically the prevailing whiteness of home-school culture, and to research the history of integration busing in Oregon, which leads to a dismaying realization about their parents’ own motives for home-schooling them. In effect, all this teaches Hazel to recognize the privilege that separates them from their coworkers. But these revelations have a second-hand quality that doesn’t feel earned. This is not for want of trying on Newlevant’s part; individual scenes are nuanced, and Newlevant does not shy away from problems. But the book’s form, as a literal memoir, does not allow for a complex treatment of the diverse work crew in which Hazel finds themself. The storytelling remains too intimately tied to Hazel’s anxieties and desires, and never builds its other characters beyond hints. Those hints are good—they suggest what Newlevant could do with a freer novelistic development of the book's themes—but everything remains keyed to the growth of Hazel’s consciousness, so that, ironically, the book’s form ends up mirroring the self-absorption that Newlevant so clearly intends to criticize. The story’s resolution, which affirms community across ethnic and class lines, feels like a lunge for closure that isn’t warranted, based on what the story gives. In short, No Ivy League feels a bit signpost-y to me, i.e. forced. Still, there are terrific things in this book. For one thing, there’s a lot of smart dialogue and physical blocking. Newlevant well captures the awkwardness of Hazel’s social moves, their blundering, unsure way of making connections, and (again) their sense of isolation. For another, Newlevant does intriguing things with design, rhythm, and the braiding of details. A wordless two-page sequence captures Hazel’s alienation from their own once-comfortable surroundings: Hazel’s animated video extolling the advantages of homeschooling (their submission to a contest among home-school students) comes up twice, and the second time we see Hazel watching it with a more critical eye, their own expressions superimposed over the video’s images: On the other hand, the book includes some narrative feints that don’t come to much, such as a subplot about Hazel’s relationships with their boyfriend and with an older supervisor (on whom they have a crush). That narrative dogleg doesn’t seem to lead anywhere—though, to be fair, one could argue that that’s the point (perhaps Hazel puts aside romance in favor of a greater self-discovery?). To me, it felt like a dangling, untied thread. Overall, I was left feeling that Newlevant’s narrative reach had exceeded their grasp. Given a conclusion that feels willed but not organically attained, I came away with, mainly, a nagging desire to learn more about what I can only call the book’s “supporting cast” (an inadvertent testimony, perhaps, to Newlevant’s storytelling potential). No Ivy League, I think, wants a form better-suited to conveying its cocoon-busting message. That said, the book is visually elegant and transporting. Newlevant is a gifted cartoonist with a keen sense of place and mood. They are also, my criticisms aside, an ambitious writer who merits following. I urge my readers to seek out No Ivy League and give it their own considered reading.

0 Comments

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed