|

Despite hard times, I've been blessed with good comics reading, especially around this winter holiday season. I've contributed a list of favorites from 2021, along with commentary, to The Comics Journal's annual Best-Of, and what they have assembled is a great resource, well worth checking out (more than 20,000 words by close to thirty different critics). Meanwhile, the slideshow below offers an expanded list of personal faves, sans commentary, just FYI. I'm sure I've missed many great comics this year, as usual. Who can keep up? Of the thirty-two comics shown below, only six or seven are clearly "for" young readers. Some are decidedly adult. I note that, once again, I've listed more books (seven) from Drawn & Quarterly than any other publisher. I've also listed four from Fantagraphics. I've reviewed four of the titles below for SOLRAD: The Online Literary Magazine for Comics and three of them here on KinderComics. The books are listed alphabetically. Click on a book's cover to go to a webpage with more info about the book: A few notes about some of the above titles:

0 Comments

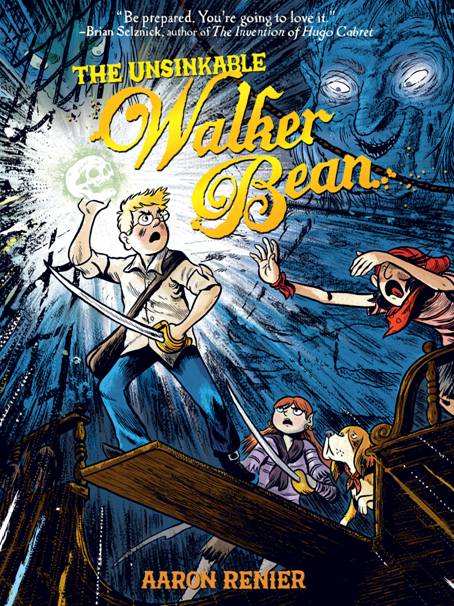

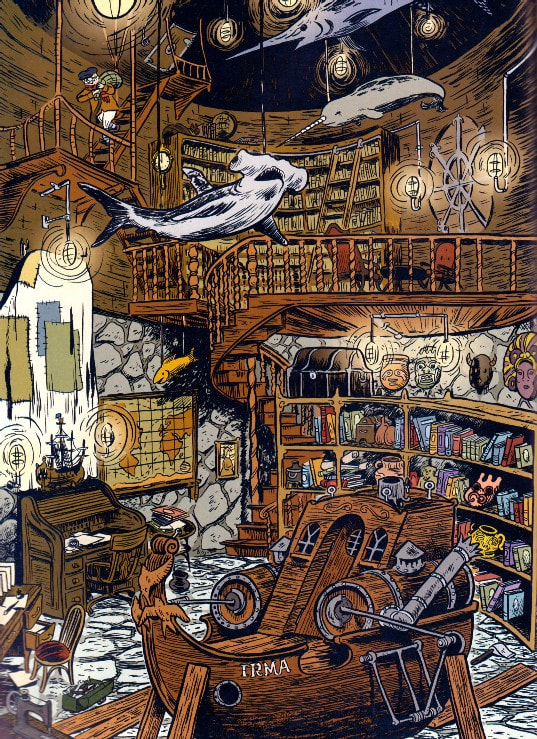

The Unsinkable Walker Bean. By Aaron Renier. First Second, 2010. ISBN 978-1596434530. 208 pages, softcover, $15.99. Colored by Alec Longstreth. (This review originally ran on the now-defunct Panelists blog in June 2011. I've revived it here and now because a sequel to Walker Bean is promised this fall. Ever the fusspot, I have not been able to avoid the temptation to trim and update, albeit slightly. - CH) Piracy on the high seas—storybook piracy I mean, the kind we know mostly from echoes of Stevenson and Barrie—remains an adaptable, nigh-bottomless genre. The piratical yarn lends itself to the dream of an infinitely explorable world, to lusty romance, oceanic myth, and shivery deep-sea terrors, all of it salted with enough bilge, filth, and real-world cynicism to sell even the flintiest skeptic. The golden age of Caribbean piracy, which even as it happened was a set of facts angling to become a myth, helped redefine the pirating life as radically democratic, an anarchic space of freedom—ironic, since it grew out of colonialism and the Thirty Years’ War. That age bequeathed us a roll call of larger-than-life persons, Calico Jack, Anne Bonny and Mary Reade, Blackbeard, and the rest: real-life opportunists from whence Stevenson distilled his great, demonic “Sea-Cook,” Long John Silver, Treasure Island’s indelible villain. Silver’s slipperiness lives on, I suppose, in Johnny Depp’s Jack Sparrow, ever scheming, ever sidling away to scheme another day. Pirates of the Caribbean reinvigorated the old genre, but with a heaping dose of hypocrisy. For example, in Bruckheimer, Verbinski, and Depp's third Pirates film (2007), the multinational juggernaut that is Disney pits globalization, in the person of the über-capitalistic East India Company, against scrappy piratical “freedom,” represented by Sparrow and his fellow rum-soaked scumbags. Huh? Couched in terms of post-9/11, post-Patriot Act resistance to a neoliberal mercantilist New World Order, that movie of course made shiploads of money. Such irony. So, the myth of the high-seas pirate carries on, its popularity an index of how we feel about the tug o’war between hegemonic authority and the individual will to live and indulge. Cartoonists in particular seem to love pirate tales and other nautical yarns, maybe because such tales make the world feel larger, maybe because they give license for scruffiness and odd character design (think Segar), maybe simply because the high seas invite so much gushing ink. A fair handful of graphic novels from recent times either plunge into the deep sea or sail off to faraway places: Leviathan, That Salty Air, Far Arden, The Littlest Pirate King, Blacklung, Set to Sea, et cetera (I bet readers can name a few others). Aaron Renier’s The Unsinkable Walker Bean (released, what, eight years ago now?) dives into the genre with a hectic, dizzying 200-page story and a surplus of delicious inky craft. Written and drawn by Renier and colored by Alec Longstreth, Bean is a beautiful, odd book aimed squarely at young readers, the first of a promised series that, it seems to me, aims to mix a carefully rigged Tintin-esque plot with the jouncing unpredictability and eccentricity of Joann Sfar, whose organic approach to both plotting and drawing probably provided inspiration. The materials are familiar enough, but the execution is, wow, crazy. The results strike me as imperfect but delightful. Walker Bean (a cartoonist’s surrogate?) is an unlikely pirate: a nervous, sensitive boy prone to doodling and mad invention, slightly pudgy and bespectacled to make him seem an unexpected hero. His emotions are worn near the surface. The plot tests his ingenuity and bravery, offering plenty of swashbuckling and catastrophic violence in the bargain. It’s sometimes bloody and boasts some real scares. Walker’s world looks like a farrago of eighteenth and nineteenth century elements—costume, settings, ships—but frankly it’s unreal, a synthetic alternate world. Per the map on the frontispiece, that world is like a distorted view of ours but bears fanciful names (e.g., Subrosa Sound, the Gulf of Brush Tail, and cities like New Barkhausen and Tapioca) alongside real ones like the Atlantic and Mediterranean. Anachronisms abound, such as a middle class child’s bedroom casually appointed with books. Stops along the way, such as the colorful port of Spithead, teem with diverse character types who lend the storyworld a distinctly postcolonial vibe. The plot, a mad, churning mess, begins with mythical backstory: a child’s bedtime story about the destruction of Atlantis. Then it veers sharply into pure breathless adventure. Young Walker, to save his ailing grandfather, must brave the high seas in order to return a maleficent artifact to its home in a deep ocean trench. That artifact is a skull of pearl formed in the nacreous saliva of two monstrous sea “witches”: huge lobster-like monsters who caused Atlantis’s fall. The skull is itself a character, evil, cackling, and seductive. One glimpse of it can send a person into shock or even death. Walker’s grandfather, an eccentric, bedridden admiral, entreats the boy to dispose of the skull, while Walker’s father, Captain Bean, a vain, greedy fool, plots to sell the skull for maximum profit, egged on by one “Dr. Patches,” a fraud and a fiend. The action, which zigzags unpredictably, includes long stretches on a pirate ship called the Jacklight. There Walker becomes an unwitting crew member, working with a powder monkey named Shiv and a girl named Genoa—an able thief and fighter who more than once nearly kills Walker. That's as close as the book gets to the excitements of courtship. The pearlescent skull is said to be a source of great power, of course, but keeps tempting would-be possessors to their doom (there’s a strong hint here of Tolkien’s one Ring). Donnybrooks and sea battles alternate with creepy scenes of the skull exerting its influence and big, splashy encounters with the horrific witches. Pages vary from minutely gridded exercises to explosive full-bleed spreads. Plot-wise, there are double-crosses, shipwrecks, and weird critters aplenty, a burgeoning cast of supporting players, and moments of tenderness, confusion, and self-realization. Walker, Gen, and Shiv are all well realized. Walker himself becomes the true hero that the title promises. In the end, things are resolved but other things left open, setting up Volume Two. Renier has not worked out his story perfectly. Honestly, I didn’t retain most of the plot details after reading through the first time; the story ran by me at a mile a minute, and I couldn’t catch it. The plot twists confusingly like a snake underfoot, and logical stretches are many; even for a pirate yarn, the book strains belief. At one point, the remains of a smashed ship conveniently drift into port. At another, the Jacklight, having been completely wrecked, is rebuilt and transformed into an overland vehicle (with wheels) in the space of a single day. In short, Renier leans on plot devices that don’t convince. What’s more, the storytelling is at times more exuberant than clear; certain double-takes and surprises confused me. Pacing and story-flow sometimes hiccup. What we’ve got here is a patently rigged plot set in an overstuffed story-world that is still in the process of being worked out. Walker Bean is a generous story, almost risibly full, but sometimes it's hard to believe. Ah, but how it testifies to the love of craft! The book’s colophon describes in detail Renier’s process of drawing and hand-lettering (on good old-fashioned Bristol board) and then the shared process of coloring (where the digital takes over). All tools and techniques are duly described, even razor-work and the use of Wite-out to vary texture. The descriptions are aimed at any reader; no prior knowledge of technique is assumed. It’s as if Renier and Longstreth wanted to let young readers in on their trade secrets. The book’s coloring, it turns out, began collaboratively: Using some old, faded children’s books for inspiration, Aaron and Alec created a custom palette of 75 colors, which are the only colors used in this book. Coloring a big book is easier when one has only a limited number of colors to choose from, and it makes the colors feel very unified. The results do exhibit an aesthetic unity, without disallowing the occasional eruption of tasty graphic shocks. In any case, the blend of line art and color—handiwork and digital—is gorgeous. Renier, if not yet a surefooted storyteller, is a terrific cartoonist. Vigorous brush- and pen-work, lush texturing and atmosphere, dramatic staging, complex yet readable compositions, and even formalist games—all these are in his ambit. Examples are legion. For instance, check out this panel depicting a bumpy ride: Or this much quieter one, depicting a secret hideout: Renier’s commitment to the work and talent for conjuring strange places and characters show in every page—and every page is different. This is first-rate narrative drawing, stuffed with beauty and promise; it takes the gifts shown in Renier’s first book, Spiral-Bound, and boosts them to a new level. Finally and most importantly, Walker Bean has soul. It makes room for emotional complexity. Minor epiphanies and finely observed silences, scattered across the book, make it much more than an opportune potboiler. Behind the book is a thumping heartbeat that testifies to a reckless love of comics and adventure. This is a yarn without a whiff of condescension: mad, high-spirited, and cool. (Volume Two is due this October. Hmm, what difference will eight years make? Also, note that KinderComics will be on summer break between now and Monday, August 20, 2018.

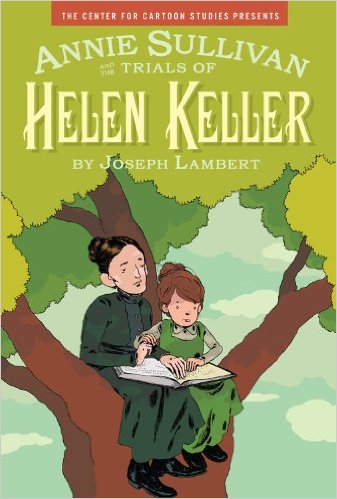

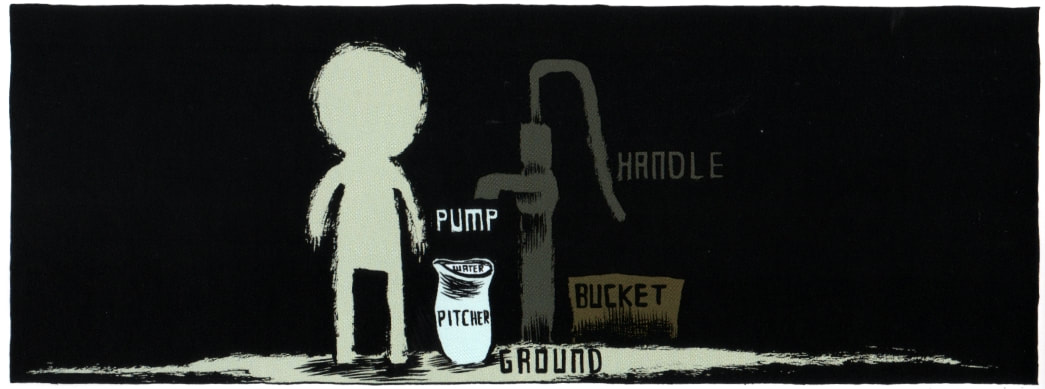

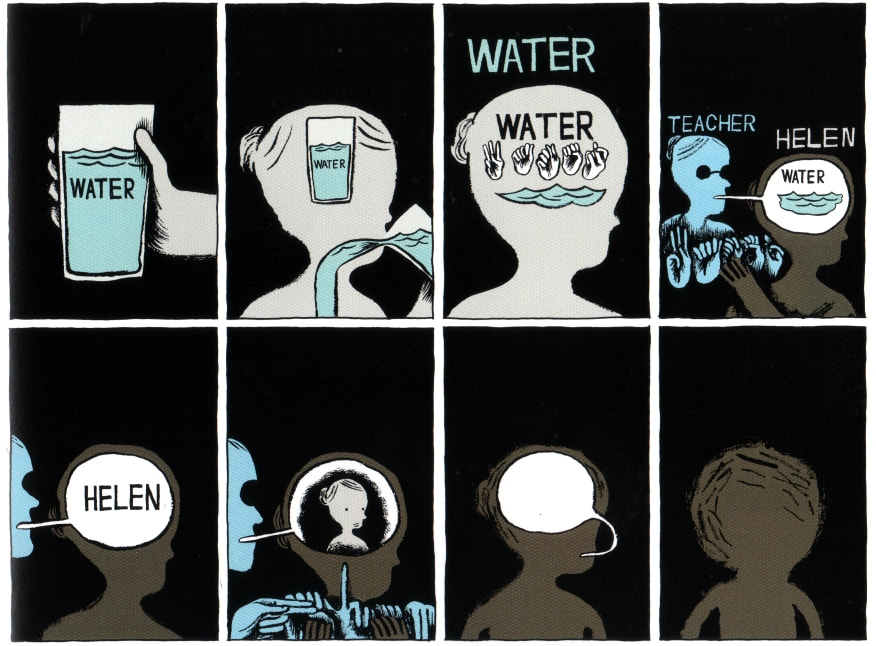

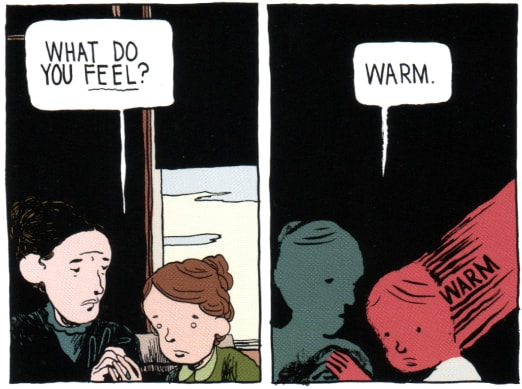

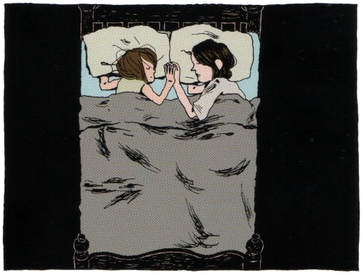

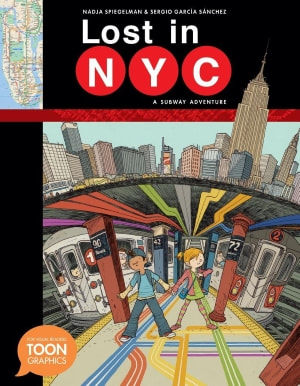

Annie Sullivan and the Trials of Helen Keller. By Joseph Lambert. Edited by Jason Lutes. Disney/ Hyperion, 2012. ISBN 978-1423113362. $17.99, 96 pages. Winner of the Will Eisner Award for Best Reality-Based Work, 2013. I have a dozen copies of Joseph Lambert's Annie Sullivan and the Trials of Helen Keller in my office. It's that good. I bought most of those copies through Alibris just over a year ago while preparing to teach my grad seminar "Disability in Comics." I had always intended Annie Sullivan to be a required book in that class, along with such other comics as Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary, The Spiral Cage, Epileptic, El Deafo, and Hawkeye: Rio Bravo. In fact Annie, along with José Alaniz's Death, Disability, and the Superhero, was one of the books that inspired me to teach the class in the first place. When I discovered that Annie was out of print, I lost my mind a bit, but then decided to scrounge up multiple used copies on my own dime and turn my office into a lending library. So, I ended up with a lot of Annie, and loaned out copies for several weeks. It's criminal that this modern classic is out of print – and I hope someone does something to change that soon. Annie Sullivan is part of a series of comics biographies packaged by the Center for Cartoon Studies for publisher Disney/Hyperion (2007-2012). These include books on Harry Houdini, Satchel Paige, Amelia Earhart, and Henry David Thoreau. All the books are hardcovers that run about 100 pages, and all are good; John Porcellino's Thoreau at Walden is wonderful. But Lambert's book, I believe, is one for the ages. Why do I admire this book so much? Lambert, whose work I came to know through The Best American Comics 2008 (edited by Lynda Barry) and then his story collection I Will Bite You! (2011), is simply a great cartoonist. His work displays a patience for careful breakdowns and repetition which approaches that of Harvey Kurtzman or of a top-notch humor strip artist. His drawing is simplified in appearance but also nuanced and emotionally precise, capable of capturing crucial subtleties of gesture and expression. Further, he has an appetite for expressing feeling and sensation through variations in traditional form; he can make a regular, unvarying grid seem musical and powerful. Feeling and sensation are the life's blood of Annie Sullivan, a book that works cannily, in an austere, rhythmically controlled way, to convey how its title characters experience the world in spite of (or through the filter of) isolating sensory impairments. Lambert does this with a poet's command of meter and a true biographer's interpretive sensitivity. One of the things Annie Sullivan does so well is inevitably, perhaps cruelly, ironic: it finds ways to visually convey non-visual experience, particularly haptic experience: the experience of handling things, of placing your hand in someone else's, of spelling things out with your fingers, and so on. Annie Sullivan taught Helen Keller, who lost her sight and hearing before she turned two, to recognize things in the world with her hands, and to communicate through finger spelling. Keller wrote in her autobiography, The Story of My Life (1903), that her tutor Sullivan revealed to her "the mystery of language," a gift that, she said, "awakened my soul, gave it light, hope, joy, set it free!" Lambert does a stunningly smart job of communicating both how Sullivan taught Keller and how hard it was. His pages convey Helen's haptic world and her opening-out into written language, using a range of techniques: tight, inescapable grids; nearly all-black panels and stark contrasts of light and darkness; isolated and stylized figures; systematic color-coding of figures and objects; inventive rendering and placement of single words; and stylized iconic hands to represent finger spelling. Formally ingenious, these techniques are also moving, for they show the extent of Helen's isolation, the intense, mutually dependent relationship between Helen and Annie, and the cascading emotional consequences of Helen's growing literacy. In a profound sense, Lambert's book is about obstacles to communication, and how, in the singular Hellen/Annie relationship, these were overleapt. Again, to render haptic experience visually is unavoidably ironic. In my class we discussed not only the formalistic means but also the ethics of this approach, in comparison and contrast to other comics' visual depictions of non-visual experience (particularly Marvel's Daredevil). Annie Sullivan and the Trials of Helen Keller cannot perfectly convey Helen's phenomenal world. It cannot help but be an ocularcentric evocation of sightless experience. That's a problem. Yet the book is a highwater mark in the synesthetic use of comics' visual form to suggest life beyond the visual; in this, it strikes me as both ingenious and sensitive. Another thing that makes Annie Sullivan so strong is its dual focus on teacher and student. Sullivan comes off, not as some beneficent "miracle worker," but as a conflicted, heroically stubborn, frank, fierce, and deeply sorrowful person, shaped by her own visual impairment, her wretched years spent living in an almshouse, the tragic loss of her brother, and her just resentment of gender convention and the straitened roles available to women in 19th century America. Sullivan appears to have been a difficult and marvelous person, sometimes bitterly acerbic, and moved by abiding grief and anger. At times Lambert depicts her teaching of Helen as autocratic, harsh, even borderline abusive. Yet he also shows how and why it worked. Lambert, that is, portrays Annie with great empathy but also unsentimental candor. The book is tough-minded, sketching in the horrors of Annie's early life discreetly but powerfully and showing her resistance to the men and women who sought to control her. What's more, in its depiction of teacher and student together, Annie Sullivan avoids the triumphal cliches of children's biography. While Lambert rightly depicts Sullivan's breakthrough with her pupil as remarkable (the famous scene at the water pump, recounted in Keller's biography and in the many versions of The Miracle Worker), that is not the end of the story, and the book's second half delves into other "trials." Chief among these is an accusation of plagiarism that hurt Keller deeply, bedeviled her early efforts as a writer, and estranged Keller and Sullivan from their benefactors in the field of education for the visually impaired. In the end, what emerges is not a simple story of Helen's triumph over adversity but a complex sense of Helen and Annie's profound dependence on one another. In fact, the conclusion of the book is oddly melancholy, offering none of the facile reassurances that ableist stories of overcoming disability tend to offer. In sum, Annie Sullivan is a brilliant feat of writing as well as cartooning and design. It really is a shame that Annie Sullivan and the Trials of Helen Keller is out of print. I can't say that enough.  UPDATE: It's back in print! As of October 2018. Yes! Lost in NYC: A Subway Adventure. Written by Nadja Spiegelman, illustrated by Sergio García Sánchez, and colored by Lola Moral. TOON Books, 2015. ISBN 978-1935179818. $16.95, 52 pages. A Junior Library Guild Selection. From time to time, Faves will offer brief capsule reviews of what I think of as key titles in my library: Lost in NYC is my favorite of the TOON Graphics to date (among the new books, that is—the translations of Fred's Philemon are also a delight). A short comic in picture book format, but as dense with detail as a graphic novel, Lost in NYC works in busy, hide-and-seek, Where’s Waldo? mode. It rewards attention, in fact perfectly demonstrates the idea that comics are a rereading medium. A valentine to New York and its subway system (the book is licensed by NYC's Metropolitan Transportation Authority), Lost in NYC depicts a school field trip to the Empire State Building, and gives a wealth of info about how to navigate the Big Apple (including a detailed subway map). Along the way, it tells the story of an awkward “new kid” in school who has just moved, feels out of place, and doesn’t trust anyone—until he and his field trip partner get lost and have to figure out how to rejoin their school group. The story depicts the new kid’s loneliness and bluff attempts to deny it with a rough honesty, but (unsurprisingly) reaches an uplifting conclusion: the field trip becomes a rite of passage, in a manner familiar from many picture books about first experiences. The pages, though, are the thing; they dazzle in their intricacy and attention to geography and culture. Sánchez’s cartooning is lively yet sly. The packed spreads, so much fun to wind through, turn up small surprises with each reading. Often the spreads use continuous visual narrative (i.e. repeated images of characters moving across a single page or opening) to show the kids negotiating the crowded city. Along the way, Lost in NYC has a lot to say about city life, mobility, access, and diversity (the art implies myriad mingled cultures). Thus the book invites comparison to other recent children's titles that envision cities as vast and pluralistic communities (for example, Matt de la Peña and Christian Robinson’s much-admired 2015 picture book, Last Stop on Market Street). It also tackles the challenges of moving and building new friendships. The plot is simple, and the outcome never in doubt, but the book puts the teeming cityscape to great use, not just as a backdrop, but as the main attraction. By way of bonus, Lost in NYC incorporates photos and historical facts (the field trip conceit allows a teacher character to lecture and explain); further, the book's back matter, as is typical of TOON Graphics, offers a wealth of contextual lore, social, technological, and architectural. Really, this is an overstuffed delight.

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed