|

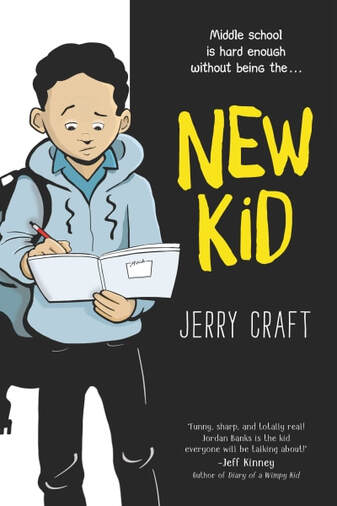

Class Act. By Jerry Craft. HarperAlley / Quill Tree Books, 2020. ISBN 978-0062885500, $US12.99. 256 pages. Billed as a “companion” to Jerry Craft’s Newbery-winning New Kid, Class Act is actually a direct sequel, following Jordan Banks and his schoolmates into the next year, but this time focusing less on Jordan and more on his friend Drew. The opening pages go to Jordan, and again his work as a budding cartoonist punctuates the story, in the form of comic strips notionally drawn by him—but Drew’s challenges, as a Black scholarship boy raised by a hard-working grandmother, soon take center stage. Drew’s pained awareness of class difference tests his friendships with Jordan and their affluent White schoolmate, Liam, and the plot tracks the awkward social negotiations among the three of them. Once again, Craft’s kids, brave and self-knowing, navigate the minefields of race and class, dogged by an inescapable sense of the things they don’t have in common; once again, their teachers are fumbling and oblivious. This time, Craft satirizes the inane efforts of their school, the tony Riverdale Academy, to extol “diversity”: teachers are dispatched to a conference called the National Organization of Cultural Liaisons Understanding Equality, and the school makes a failed effort to “adopt” a sister school whose working-class students of color don’t know what to make of Riverdale’s privileged, “bougie” atmosphere. As in New Kid, Craft observes all this in an amused, good-humored way, while never forgetting that difference can make all the difference. One tense scene depicts Jordan’s father being stopped by a White cop when driving in Liam’s posh neighborhood; moments like that affirm that Craft is playing for keeps, drawing out humor from real pain. Class Act, then, is smart and careful as well as high-spirited – though its story, I think, is more diffuse than that of New Kid, its stakes not quite as clear. (It would help to reread New Kid just before reading this one.) The book is busy and teems with in-jokes, including nods to comics and children’s book authors; sidelong gags are everywhere, to the point of distraction. More impressive is Craft’s diverse cast of distinctive, well-defined kids, many of whom get moments in the spotlight; they actually talk to each other, in courageous, meaningful ways, and Craft understands the subtle dynamics among them. You can tell he likes them. I confess that the art, with its jumbled, cut-and-paste style, clip-art elements, and CG backgrounds, put me off at first (I felt the same about New Kid). The work has an overbusy finish that mixes cartoony flatness with gradient coloring – an uneasy compromise. But Craft builds smart pages, and his socially engaged storytelling, once more, rings sharp, wise, and true. Dancing at the Pity Party: A Dead Mom Graphic Memoir. By Tyler Feder. Dial Books, 2020. ISBN 978-0525553021, $US18.99. 208 pages. Tyler Feder’s mother Rhonda Feder (née Hoffman) died of cancer when Tyler was nineteen, more than ten years ago. This memoir recounts Rhonda’s illness and death, her funeral, and the enduring sadness that has been part of Tyler’s life ever since—sometimes a still-raw, lacerating grief, sometimes a bittersweet nostalgia. That may sound just about unendurable: a self-pity party indeed. But what this book really does is pay homage to Rhonda Feder, evoke her particular, idiosyncratic self, and capture the way profound memories, very specific and odd memories that no one else could understand, arise unpredictably from quirky particulars and chance encounters. Yes, the book depicts, in fact enacts, grieving as a process, one that never quite ends, but it does so with verve, comic frankness, and surprisingly many laughs. In fact, at first, in the book’s opening pages, I wasn’t ready for Feder’s almost nonstop humorous flippancy, her many comic asides, satiric observations, and zingers. This sort of larking around in the shadow of death seemed like the very definition of Too Soon (although her mother died so long ago). To me, Feder’s approach at first felt too self-involved. But soon, very soon, the book crafts a precise portrait of Rhonda as a personality, lovingly remembered in all her quirks, the emotional, mental, and physical subtleties that made her who she was. Her eccentric liveliness, and that of her family, come through strongly, and Feder, in an unassuming and uncluttered style, balances deep sadness and irrepressible good humor, in a lovely, unforgettable tribute. Helpfully didactic at times (“Dos and Don’ts for dealing with a grieving person”), the book is mainly witty, personable, and compulsively readable—a remarkable example of how art, as Feder says, can “turn the crap into something sweet.” Little Lulu: The Fuzzythingus Poopi. By John Stanley, with Charles Hedinger, Irving Tripp, et al. Edited by Frank Young and Tom Devlin. Drawn & Quarterly, 2020. ISBN 978-1770463660, $US29.95. 276 pages. Lovingly edited, gorgeously designed, this second volume in Drawn & Quarterly’ deluxe hardcover Little Lulu series reprints more than thirty stories and strips, and a score of beautiful covers, that ran in the Dell comic book series circa 1949-1950. Written and laid out by John Stanley, these brilliant, economical, tightly wound comics were among the best of their time. They hold up well. Much has been said about Lulu as a feisty feminist icon who gets the drop on the sexist, obtuse, often mean-spirited boys in her neighborhood, and that’s true (the book’s introduction by Eileen Myles underscores that point); I was also struck, though, by the notes of human vulnerability and doubt in her characterization, by the signs of frailty and uncertainty that Stanley’s heroes often show. Lulu can be bullied, and Lulu can be hurt, but that makes her victories all the sweeter—she has real character. Stanley packs a surprising amount of human complexity into these condensed fables and gags. The tales are often absurd, sometimes satirical (such as “The Old Master,” a takedown of the art world), and always exquisitely timed, with gags and payoffs that depend upon very precise rigging. D&Q’s Lulu series is one of the best things happening in comics right now, even though the comics themselves are old. Drawn & Quarterly provided a review copy of this book.

0 Comments

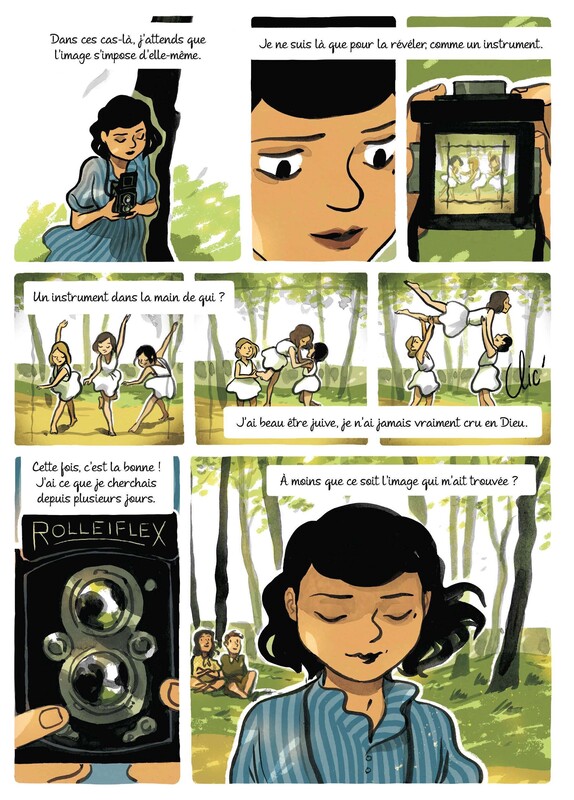

Catherine’s War. By Julia Billet and Claire Fauvel. Translated from the French by Ivanka Hahnenberger. HarperAlley, 2020. ISBN 978-0062915597, $US12.99. 176 pages. Catherine’s War is a finely shaded, beautifully cartooned, and engrossing book that ends much too abruptly. A historical novel stenciled from real events, it has been translated from the Angoulême Youth Prize-winning BD album La guerre de Catherine (Rue de Sèvres, 2017), which adapts Julia Billet’s prose novel of the same name (2012). Billet’s novel itself freely adapts, or at least draws inspiration from, the wartime story of Billet’s mother, Tamo Cohen, one of thousands of hidden children uprooted by the Holocaust: Jewish children sheltered from the Nazis, often in Catholic convents or among Gentile families. In real life, Tamo Cohen did attend the Sèvres Children’s Home (in fact a progressive, student-centered school), as does the protagonist of this novel, Rachel Cohen, and she did flee the Nazis, and she was renamed to pass as a Gentile, just as Rachel here is renamed “Catherine Colin.” But, as Billet admits in her notes, the story of Catherine’s War “remains a story”—a historical fiction interwoven with truths. Billet imagines Rachel/Catherine as a young photographer whose images of WWII are successfully exhibited in a Parisian art gallery soon after the war (an exhibition that replays many experiences depicted earlier in the book). Further, Rachel’s narration, implicitly, comes from her journal—so, she is an artist in words as well as pictures. In that sense, Catherine’s War becomes a Künstlerroman as well as a wartime tale of life on the run. Thematically, it reminds me of books like Whitney Otto’s ensemble novel Eight Girls Taking Pictures (2012), a fictionalized biography of eight women photographers, and comics like Isabel Quintero and Zeke Peña’s Photographic (2017), a YA biography of famed Mexican photographer Graciela Iturbide. Reframing Tamo Cohen’s story within the history of photography, Billet casts her mother, or rather Rachel, as a visual witness to the terrors of war. Armed with a Rolleiflex (like Robert Capa – or Annemarie Schwarzenbach?), the fugitive Rachel/Catherine becomes a chronicler as well as autonomous artist, even as she rushes from one shelter to the next to evade the Nazis. For all that, Catherine’s War is not explicitly violent. Though fear is ever-present, intimations of war and Holocaust are discreet; we never see the dreaded roundups or camps, or combat (though overheard dialogue among Resistance fighters does imply sabotage). The point of view is limited to what a child in hiding, pretending to live out her normal life, might have witnessed. Trauma is suggested by the extent to which Rachel and other young people help each other cope with it. The various children depicted (the story begins at the Sèvres home, and Rachel most often travels with other kids) are wounded by the shocks and partings they have to endure, yet they are resourceful, brave, and unselfish—not to the point of absurd angelic idealization, thank goodness, but in a tense, believable way. (Billet’s trust in young people mirrors the radical teaching philosophy of the Sèvres school.) Multiple scenes depict the challenge of trying to keep cover stories straight, the distrust stoked by constant surveillance, and the dread of giving the game away. Yet the novel is so discreet that it takes Billet’s endnotes to flesh out the terrible context of WWII. Those notes clearly anticipate a young audience, and I note that the book is blurbed by a notable writer of children’s nonfiction, Susan Campbell Bartoletti, whose work (Hitler Youth, Kids on Strike!, etc.) often extols young people’s activism and recounts harrowing historical facts with candor but also due sensitivity. Decorous would describe this book’s approach: from the story’s quiet hinting, to Claire Fauvel’s rippling brush-inking, gentle watercolors, and borderless panels, to the prim digital lettering (by David DeWitt). A genteel aesthetic overlays everything, conferring delicacy despite the nightmarish world evoked. What makes all this work is Fauvel’s patience, empathy, and attention to detail: from the opening pages, she tracks Rachel and the other characters with exquisite care, and their feelings, both spoken and unspoken, register honestly. Fauvel’s visual storytelling, if understated, is fluid and confident, moving characters about gracefully and capturing unwritten nuances in most every scene. She really cares about these characters. In short, Catherine’s War is smartly laid out, superbly drawn, and piercing. (For insight into Fauvel's process, and the book's production, see Billet's VanCAF presentation from last spring: a slideshow and talk captured on video, subtitled in English.) Not everything in the book works. There are moments where the book seems determined to spell out, rather than suggest, its messages—passages that seemed forced. In particular, a postwar scene depicting the ritual shaming (head-shaving) of French women accused of Nazi collaboration seems underdone; it doesn’t explain what’s at stake, and Rachel’s rejection of the shaming mob doesn’t register (though Billet’s endnotes work hard to underscore the didactic point). Also, as the book accelerates toward its end, things happen rather too fast. Both a crucial relationship and the postwar arc of Rachel’s life are sketched in abruptly over the last couple of pages. (It turns out that there’s a sequel, published in French in 2020, so perhaps the ending was meant to be a springboard?) When I turned the final page, I felt as if I was still in midair. That said, the gnawing dissatisfaction I felt got me to reread the book, which sharpened my appreciation of Fauvel’s subtle artistry. As I say every so often, I’d be glad to read more.

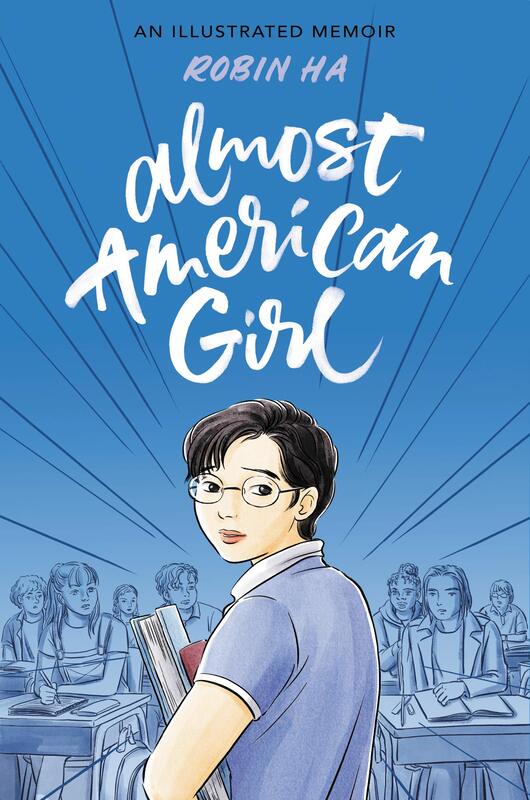

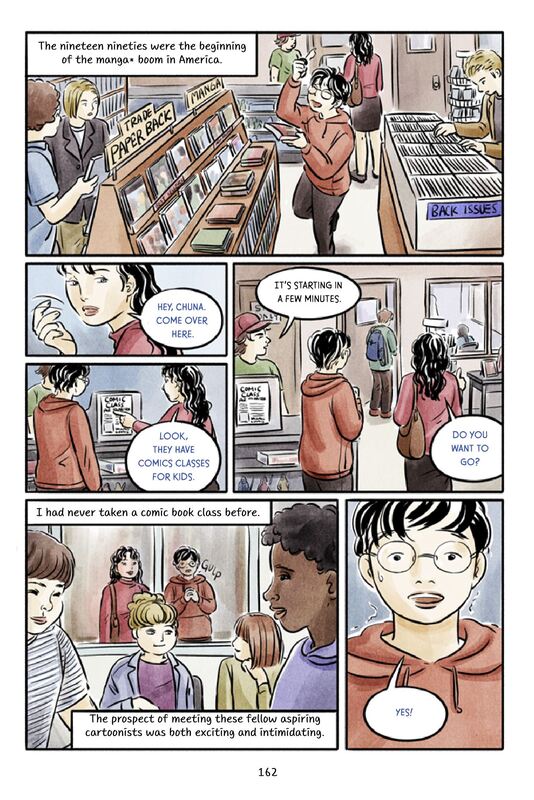

Almost American Girl. By Robin Ha. Balzer + Bray / HarperAlley. Paperback: ISBN 978-0062685094, US$12.99. Also in hardcover, Kindle, comiXology, and Nook. 240 pages. Robin Ha’s Almost American Girl, a Korean American memoir of emigration and acculturation, evokes hard truths and traumatic memories through a mostly gentle, almost decorous style. The style belies Ha’s toughness. A complex story of cultural displacement and loss, but then again gradual near-assimilation—or, better, ongoing negotiation of identity—Almost American Girl boasts a delicate watercolor aesthetic and, by contrast, stilted digital lettering. The style is sometimes straitened or stiff, yet tender and personal; the balance suggests both tentativeness and poise. I confess, I didn’t warm to it easily—but Ha’s story has stayed with me, provocatively. Young Robin, raised in Seoul, suddenly finds herself uprooted and forced to adapt to life in the US. Her mother, a single parent, makes that choice, indeed all the choices, for them. Ha’s complex relationship to her mother—who at first, it seems, did not want this book to get made—accounts for Almost American Girl’s pointed, unsentimental, and clear-eyed qualities. The book relives Ha’s memories of anger toward her mother, which could not have been easy to set down on the page, but also portrays her mom as a self-driven woman determined to break out of a South Korean society premised on gender conformity and suffocating moralism. Gradually, Robin develops empathy for her mother’s struggles, even as she learns to be critical of stereotypic gendering in her own life—and it is her (re)discovery of comics as an artistic outlet, a move encouraged by her mom, that enables Robin to stake out these positions. So, to say that Ha’s treatment of her mother is necessarily double-edged would be an understatement. The negotiations behind the book’s making must have been complicated. Just so, the finished book is hard and sort of unfinished. Much of it replays old hurts with fresh anger. In the home stretch, though, Ha fast-forwards into life changes that bring a warmer, more resolved ending; the book seems to leapfrog to its finish. This shift perhaps comes a bit too fast, reflecting, I suppose, the YA genre’s demand for at least some provisional resolution. However, to Ha’s credit, hanging questions remain. The result is clear but not pat, and emotionally rich. Almost American Girl joins other graphic memoirs of divided identity and enculturation in the US: comics about immigrants and immigrants’ children working their way into a robust but ambivalent sense of Americanness (Thi Bui, say, or Malaka Gharib). In this post-Raina moment of comics memoirs for young readers, the graphic story of renegotiated identity has become a distinct and powerful vein of storytelling. Ha adds worthily to that growing list, with work that is at once aesthetically subdued yet piercingly written. It’s very good, and I imagine it will make a big difference for many readers. PS. Dig Ha and Raina Telgemeier’s online panel from the recent Comic-Con at Home: a warm, collegial chat (with some drawing!). This has been one of my favorites of the many online “convention” events I’ve watched recently; you can tell that these authors are used to fielding questions from readers young and old. It is hard for me to imagine a Comic-Con panel like this fifteen years ago. Thank goodness the world keeps changing! Here's the video: Also, Robin Ha has a nice how-to / process video on YouTube, from this past May, courtesy of Epic Reads: see here.

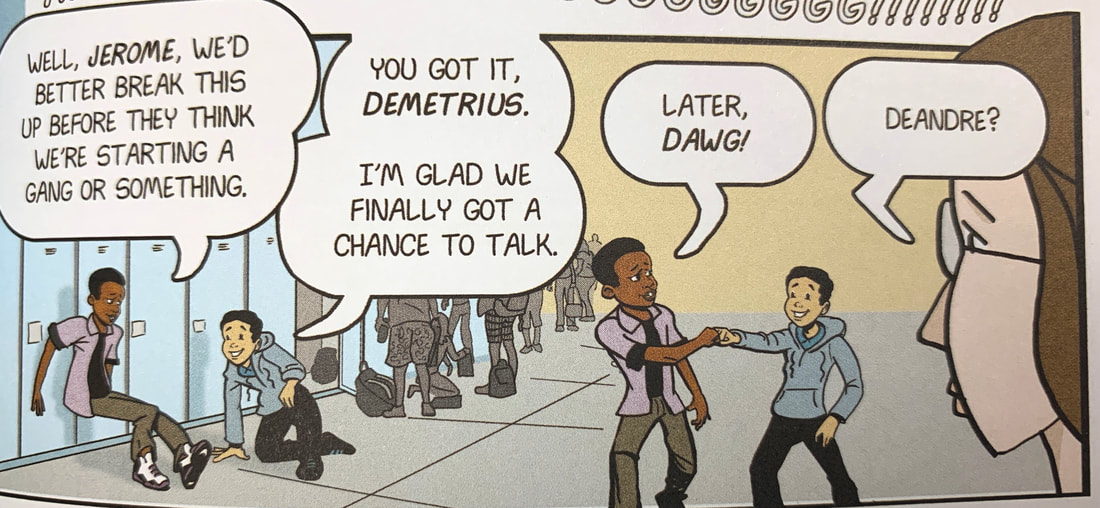

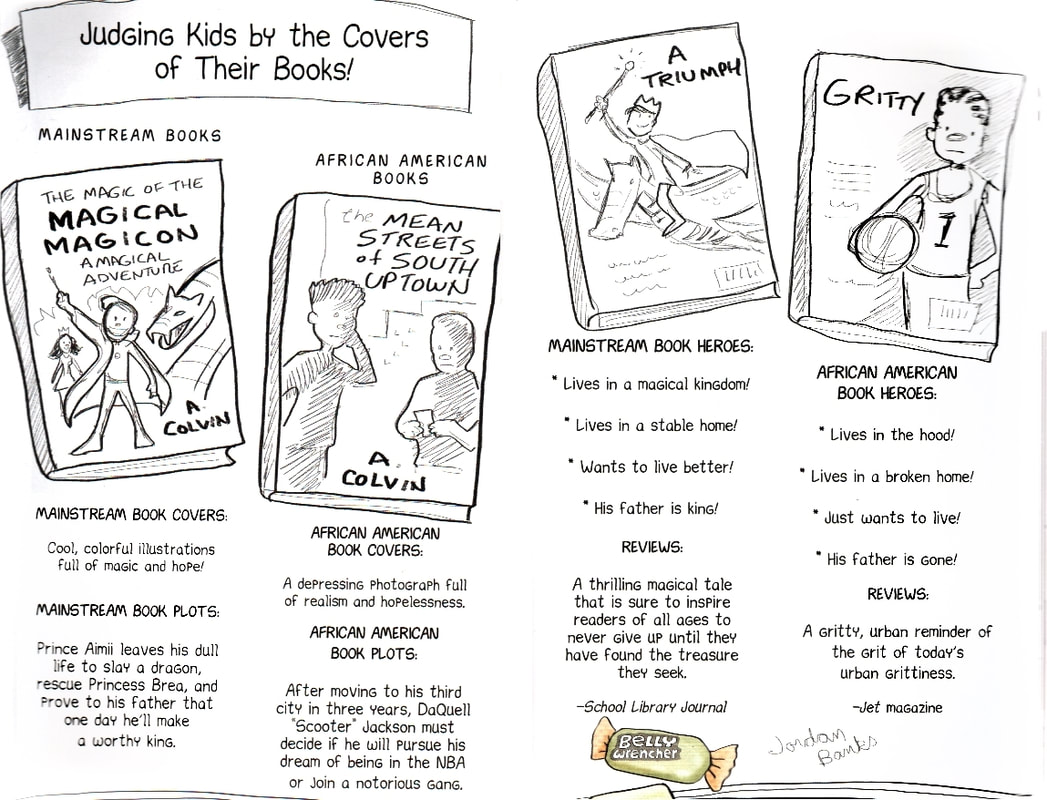

New Kid. By Jerry Craft. Color by Jim Callahan. Harper. ISBN 978-0062691194 (softcover), $12.99; ISBN 978-0062691200 (hardcover), $21.99. 256 pages. A month ago, Jerry Craft’s graphic novel New Kid became the first comic to win the coveted Newbery Medal for children’s literature. I came to New Kid late, and KinderComics readers may remember that I did not include it among my faves of 2019. I wish I had. I confess I put off reading New Kid because I did not love its graphic style, which struck me as cobbled together digitally, with elements seemingly cloned, rescaled, and reused across its pages. At first the work looked patchy to me, compositionally choppy, and too tech-dependent for my tastes. I didn’t see the visual flow or elegance of design that I tend to crave. So, I was closed-mind about this one, I have to say. (This would not be the first time my aesthetic preferences blocked me from recognizing good work. For instance, I recently read Maggie Thrash’s fine comics memoir Honor Girl, done in a seemingly naive watercolor style, and realized that I had been avoiding that one also. I had sold it short.) New Kid deserves better from me. It’s an excellent school story, not only smartly written but visually clever and insinuating throughout. Craft, with exceeding sharpness, depicts African American scholarship boy Jordan Banks and his private school mates at awkward intersections of race, class, and gender. Indeed New Kid, with miraculously high spirits, examines the effects of racism and classism without ever actually breathing those words. Craft is astute and at times can be blunt, but is also endlessly subtle; his touch is marvelously light, yet telling. New Kid manages to be hopeful and often funny, even while acknowledging racism as both systemic feature and stubborn habit. The story of one school year, New Kid gently critiques the class aspirations of private school parents, the casual racist carelessness of teachers, and the blunders of overcompensatory liberal tone-deafness, all while painting Jordan and his fellow students as canny survivors. The book abounds with sly, knowing recognitions, unexplained but pointed, including many gags that show Jordan trying to deal quietly with racial and class-based awkwardness. A middle-class Black boy in a (to him) new school that defines the very notion of privilege, Jordan is alive to the implications of every social move. Craft’s approach is at once realistic, worldly, amused, jaded even, and yet guardedly optimistic; he is properly impatient with ingrained prejudice, yet fatalistically aware that, well, young people have to get on in this broken world. New Kid humorously acknowledges the ways young people of color are too often seen, or rather mis-recognized, and fences smartly with the usual stereotypes about young urban Blackness. The school kids mostly come out well here: they see and deal with social inequality and the willed blindness of adults while upholding their sense of humor and camaraderie. Running gags and droll in-jokes are everywhere: a kind of code and coping mechanism among the kids. For example, Jordan and his classmate Drew call each other mistaken names throughout, mimicking the cluelessness of their white teacher who cannot distinguish one Black student from another. The jokes in New Kid are not just funny, but insightful—as are the young people who tell them. One of the best things in New Kid is a self-reflexive spoof of children’s and young adult publishing that mocks the narrowness of Black depictions in the field. This spread made me laugh out loud (please forgive my crummy scan): If, as Philip Nel argues in Was the Cat in the Hat Black?, the cordoning off of genres marks a de facto line of segregation (Genre Is the New Jim Crow, in Nel’s phrasing), then Craft gets this exactly, and takes the whole publishing field to task. Indeed, the sight of a “gritty” novel for Black teen readers becomes a repeated joke in New Kid, one that stings with its insight but is also downright hilarious. Bravo! This is a supremely wise and charming book that jousts with, and defeats, a thousand cliches.

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed