|

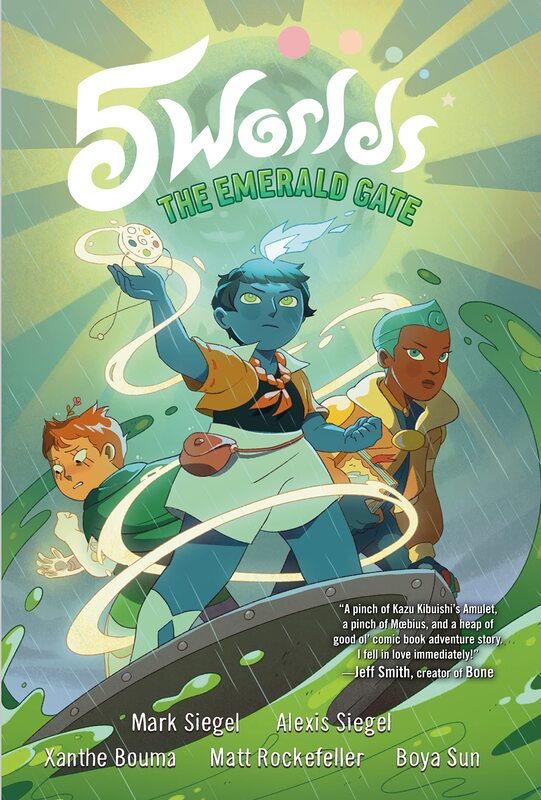

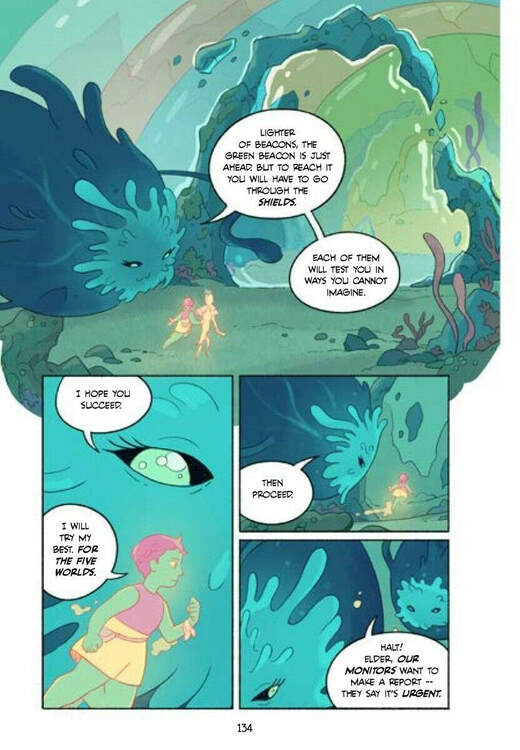

5 Worlds: The Emerald Gate. By Mark Siegel, Alexis Siegel, Xanthe Bouma, Matt Rockefeller, and Boya Sun. RH Graphic/Random House, 2021. The 5 Worlds series (five books set on five planets, published over roughly five years) has always been a high-wire act, balancing space fantasy, ecofiction, and Miyazaki-esque tropes with allegorical broadsides against neoliberalism and right-wing populism—all of this served up by a complex collaborative team consisting of five geographically dispersed co-creators. The way they have all worked together is a bit of a miracle. I’ve reviewed every volume (one, two, three, four) and keenly followed the evolving story of heroes Oona, An Tzu, and Jax and the many co-revolutionaries and loved ones they’ve gathered along the way. The series reaches it big finish with The Emerald Gate, and it’s a corker of a climax. Overall, the series has proved smart, bold, and very good—though I must admit it has left me with a sort of gnawing dissatisfaction, somehow. Pointedly allegorical from end to end, 5 Worlds has targeted egotism, greed, environmental carelessness, demagoguery, and (most clearly in Book 5) gradualism and hidebound deference to tradition, as its youthful heroes throw off the shackles of what has been done in favor of what can be done. The story is unabashedly progressive, topical, and on the nose. The Emerald Gate, dedicated to “the young people not waiting for permission to bring long overdue change to our world,” casts lead heroine Oona as a Greta Thunberg-like climate activist who must defy authority and take big risks to make big changes. The Five Worlds of the title are suffering a gradual ecocide—that is, dying of heat death—but an oily Trumpian oligarch (possessed by an ancient dark force) is trying his damnedest to smother that fact. Only drastic measures can save the day. This final volume’s signature phrase, Green doesn’t wait for permission to grow, signals Oona’s shift from diffidence to absolute certainty; she is done questioning, and now knows the way. Though the book takes time to sow little seeds of doubt (What if Oona’s plan only plays into the villain’s plan? What if the perfect solution turns out to be perfectly disastrous?), there really is no doubt: Oona and her fellow heroes must do something radical, must play for the highest stakes, if they are to save the Five Worlds. They must rebel. Oona must rebel. Above all, she must embody moral and political certitude. The Emerald Gate, more than its four predecessors, reveals an odd tension: between the radically egalitarian and democratic spirit to which the series aspires, and, on the other hand, the near-deification of Oona, the fated heroine who must give her all for the cause. In the home stretch, Oona undergoes a sort of ritual testing, running a gauntlet of five “filters” or “shields,” that is, moral and psychological trials, so that she can recognize “the truth.” Through this ritual, Oona rejects tradition and hierarchy, factionalism and rage, egocentrism, and personal desire. In effect, she rejects the novel’s version of neoliberalism. But this renunciation is the key to her final apotheosis; even as she rejects crude individualism, she is affirmed as The One who can channel the virtues and energies of all Five Worlds. While every member of Oona’s team plays a vital part in the novel’s ending, their final success depends on deferring to Oona’s vision and artistry (“Do not tell me your plan. I trust you”). In this way, the story uneasily mixes the political and the mythic—and remains, perhaps in spite of itself, a heroic fantasy in awe of individual gifts, somewhat at odds with its collectivist ethos. What makes all this work is that there is a price to pay. I won’t get into the details; suffice to say that Oona’s apotheosis entails a change of state and a goodbye—though also a sort of opening into ineffable new possibilities. Her transformations are so dramatic that she cannot return to ordinary life. Nor can she be quite understood. To resolve the story, Oona must escape the containment of the story, must step outside the frame her friends (and we readers) understand. Channeling the powers of the Five Worlds means being more than a person, and so there is lovely sense of consequence to the ending. What I’m talking about is not quite the wounded bittersweetness of Frodo Baggins at the end of The Lord of the Rings, but at least something that surprised me and made me reread the last few pages with care. The Emerald Gate well and truly finishes the story of Oona that began in 2017 with The Sand Dancer. I look forward to rereading this series all at one go. Aesthetically, it’s remarkably cohesive, a seamless collaboration despite the complex interworking it so clearly required. The Emerald Gate is (as I’ve come to expect) a sumptuous feast of worldbuilding and of deft, surehanded cartooning. The payoff in the end is rousing and full of feeling, enough to knock me for a loop. Overall, the book comes across as a paean to the indomitable spirit and visionary energy of the young—though this is one of those texts that, in my Children’s Literature classes, we’d be cross-examining to see what its construction of youth says about the hopes and needs of adults. While 5 Worlds depicts young people as radically free, it follows a didactic agenda that tries to teach young readers to be those free spirits, and to save us all. Ultimately, it rejects the shaded, tragically complex vision of one its avowed inspirations, Miyazaki, in favor of an unequivocal ending in which hesitation and gradualism can be identified with a hated Dark Lord and summarily banished. It’s all about the certainty of Truth. Yet the skeptic in me wants something a shade more tangled and complicated. In the end, I found myself wondering if the utopianism of 5 Worlds conflicts with some of the messages it has been trying so hard to convey. But, oh, what a rapturous five-year ride.

0 Comments

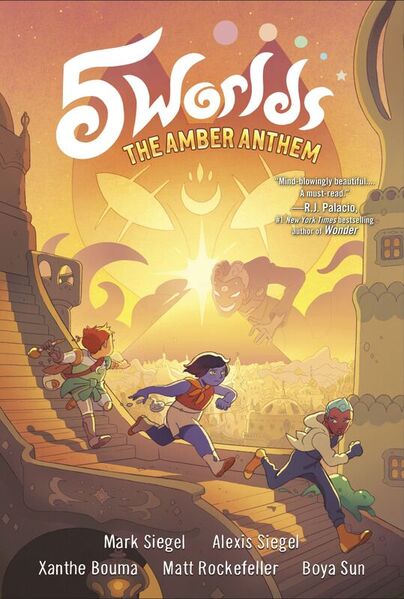

About eight weeks ago, I announced that KinderComics would be “taking a roughly six week-long break.” Every time I say something like that, I sigh—and sigh again when, eventually, tardily, KinderComics returns. So, okay, here I go again: Scheduling pressures under COVID, the endlessness of preparation and grading in my online teaching, and a looming sense that the world is going wrong, that it could explode any day—these things have been getting in my way. I admit I often consider closing this blog and moving on. Only reading and writing pleasure draws me back. So, let me switch gears and get down to the stuff that matters: 5 Worlds: The Red Maze. By Mark Siegel, Alexis Siegel, Xanthe Bouma, Matt Rockefeller, and Boya Sun. Random House, May 2020 Paperback: ISBN 978-0593120569, $12.99. Hardcover: ISBN 978-0593120552, $20.99. 240 pages. Who is the author of Five Worlds? This sprawling adventure series is the work of what seems to be an impossibly harmonious five-person team; somehow, the results comes across as the work of a single hand. Aesthetically, the series is gorgeous, a real feat of cartooning. Structurally, it’s tricky, with a modular, five-book shape, each book color-coded and focusing on a different world and different puzzle to solve (or secret to uncover, or McGuffin to find). Politically, it’s timely, with ever more obvious allegorical broadsides against Trumpism, neoliberalism, and xenophobia; in this progressive fantasy, world-building goes hand in hand with topical commentary that feels, as I’ve said before, on the nose. Alongside its familiar genre elements—the hype invokes Star Wars and Avatar: The Last Airbender as comparisons, but Miyazaki hovers over the whole thing too—Five Worlds conjures the anxieties of our times, and scores palpable hits against “fake news,” noxious right-wing media, climate change denial, and the shamelessness of greed-as-doctrine. KinderComics readers will know that I’ve been fairly obsessed with this series, reviewing Volumes One, Two, and Three in turn, and that I found the third, 2019’s The Red Maze, the most successful thus far at balancing genre convention, fresh discovery, and political relevance. With the latest volume, The Amber Anthem, the series has reached its fourth and penultimate act, and appears to be barreling toward a big finish. It’s actually a bit of a blur. In The Amber Anthem, the McGuffin is a song—the anthem of the title—and the story’s climax depends on thousands of voices lifted in song together, in a vision of peaceful yet powerful resistance that suggests real-world analogies: the Movement for Black Lives, and the recent surge in street protests despite COVID. (The book must have been written and drawn before that surge, and before the pandemic too, but its spirit of protest makes such analogies irresistible.) Here the dominant color is yellow, and the world is Salassandra, a planet briefly glimpsed before but now the center of the action. Our heroes, Oona, An Tzu, and Jax Amboy, once again seek to relight a long-quenched “beacon” in order to save the Five Worlds from heat death and environmental collapse. The Trumpian villain, Stan Moon—a host for the dreaded force known only as The Mimic—redoubles his attacks, even as Oona, An Tzu, and Jax take turns in the spotlight. The plot, as usual, is complicated, a tangled quest. Ordinary Salassandrans alternately help and hinder that quest (many having been persuaded that our heroes’ mission means ruin for the “economy,” and so on). The climax depends upon bringing together people of “five races.” Jax, a sports star, joined by a beloved pop singer, uses his celebrity to draw those people together—a handy metaphor for the way pop culture may provide opportunities for activism and community-building when official politics becomes hopelessly corrupt. Along the way, Anthem clears up several nagging mysteries, in particular the backstory of An Tzu (whose body has been, literally, fading away, book by book). I expected as much. Each new volume of Five World has delivered some big reveal or transformation for one of the heroes; now, with An Tzu’s history disclosed, the series seems poised for its finale. There’s a sense of unraveling complications here, yet of a tense windup at the same time. I confess that the big reveals here, though some of them came out of left field, didn’t leave me gaping or even happily stunned. Instead, I found myself jogging, not for the first time, to keep up with the frantic plot. Reveries and remembrances, sorties and missions, switchbacks and betrayals: it's a lot. The climax, though, is beatific: a shining vision of pluralism and collaboration and a lyrical evocation of “many strands…interweaving.” It's a triumphant close, but a corking good cliffhanger in the bargain, introducing a new moral dilemma and setting the stage what promises to be a breathless final volume. I’m keen—Five Worlds has been an annual stop for me, and I look forward to seeing how it all plays out. Five Worlds is a marvel of coordinated effort and cohesive design; again, its author-in-five-persons communicates like a single voice. Its world-building is lovely—I would happily pore through sketchbooks showing the collaborative process behind these books. That said, I’m starting to wonder whether the series’ complex rigging, breakneck plotting, and moral certainty are robbing it of some degree of complexity (as opposed to structural complicatedness, which it has in spades). The effect of Five Worlds on me, so far, has been like that of an action movie with soul, but its compression and momentum have not allowed for the sort of complex characterization that marks, say, Jeff Smith’s Bone, whose deepest characters, Rose Ben and Thorn, are sometimes at odds and go through hard changes. Five Worlds gestures toward the hard changes, and has enough soul to tend to the hearts and minds of its heroes, but everything feels a bit rushed. Despite the loveliness of the proceedings, then, at times the generic tropes come across as just that (Stan Moon, for example, speaks fluent Villain). When stories are ruthlessly streamlined, often what we remember are the clichés. I hope not. I look forward to the last chapter, The Emerald Gate, which I hope will bring everything—world-building, political urgency, and layered characterization—into balance one last, splendid time. When I open up the fifth and final volume, I’ll be holding my breath.

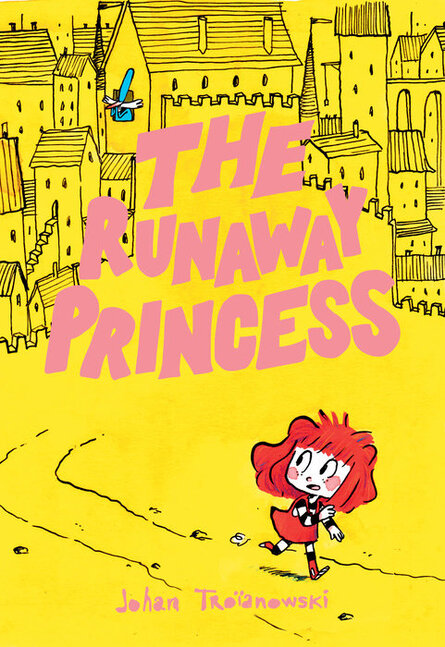

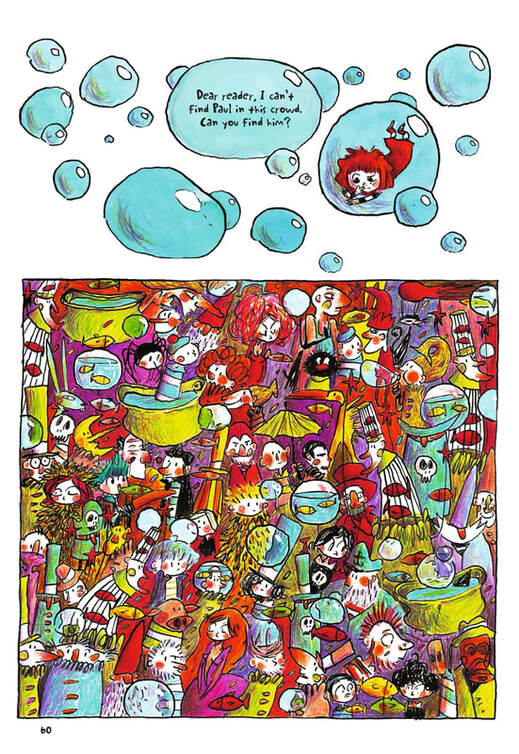

The Runaway Princess. By Johan Troianowski. Translated by Anne and Owen Smith; designed by Patrick Crotty. RH Graphic, ISBN 978-0593118405 (softcover), $12.99. 272 pages. January 2020. The Runaway Princess, a giddy, self-aware romp, celebrates doodling, play, and spontaneous worldbuilding. Its title and cover may suggest a feminist fractured fairy tale of the Princess Smartypants variety, but it’s really a Baron Munchhausen sort of yarn, a happy riot whose main lesson is pleasure. Not so much a deliberate novel as a spree, it showcases author Johan Troianowski’s freewheeling cartooning while riffing on familiar stuff. The first release under RH Graphic, Random House’s new comics imprint, The Runaway Princess translates Troianowski’s French series Rouge (2009-2017). The Rouge of the original becomes Robin here; she’s a wayward young adventuress with a touch of Little Red Riding Hood but also Pippi Longstocking. The world she travels is a vehicle for exuberant drawing and vivid, crayon-and-ink coloring. It’s also chockablock with drive-by homages to children’s literature, from classic fairy tales to Alice to The Wind and the Willows. Essentially, The Runaway Princess collects three rambling quests that consist of hide-and-seek, maze-walking, and casual discovery. In the first, Robin traverses a dark and threatening wood, where she befriends four lost kids, all boys, whom she leads out of the wood, to a strange city and festival. There some of the kids get lost again and have be found. In the second tale, Robin and the boys discover an underground world, where Robin befriends a witch, until the tale takes a darker, Hansel and Gretel-like turn; more hiding and chasing ensue. In the third, Robin and boys are cast away on an island, where a benevolent explorer introduces them to the culture of the Doodlers: small creatures who make art. Treasure-hungry pirates attack, and again the plot affords plenty of frantic running around. Notably, the book includes self-reflexive, interactive pages that invite the reader not just to read but to do things: solve mazes, shake the book, etc. That is, The Runaway Princess is a game of sorts; the book knows that it’s a book, and invites us to have fun with that fact. If Troianowski’s loose, scribbly style recalls Joann Sfar or Lewis Trondheim, his metatextual play recalls Fred’s classic Philemon series: as the plot bounces from one craziness to another, there’s little sense of danger or poignancy, more a benign, Fred-like absurdism and self-awareness. Troianowski excels at weird places—City of Water, Island of Doodlers—and favors graphic playfulness over tight logic, but it’s the direct appeals to the reader that make it work. Though The Runaway Princess would be at home alongside Philemon, or, say, Sfar’s Little Vampire, it lacks the philosophical weight of Fred and odd tenderness of Sfar, and sometimes reproduces Eurocentric, colonialist clichés (as in the ethnological Doodlers plot). Yet the book fizzes like a rocket, and cheerfully celebrates creativity (in this, it resembles, say, Liniers’s Written and Drawn by Henrietta). In sum, it’s is a breezy, inventive launchpoint for RH Graphic, and recommended.

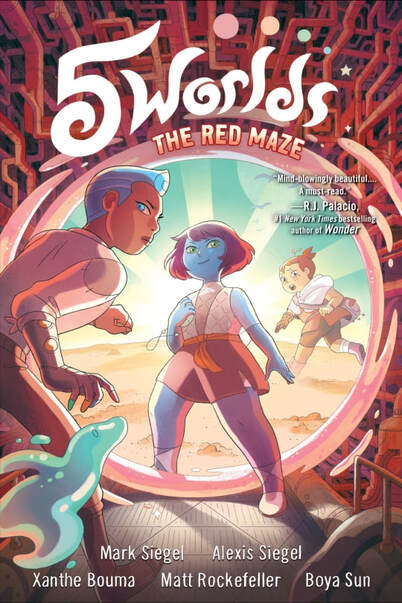

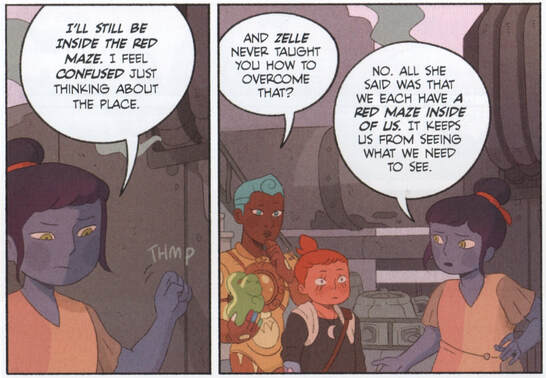

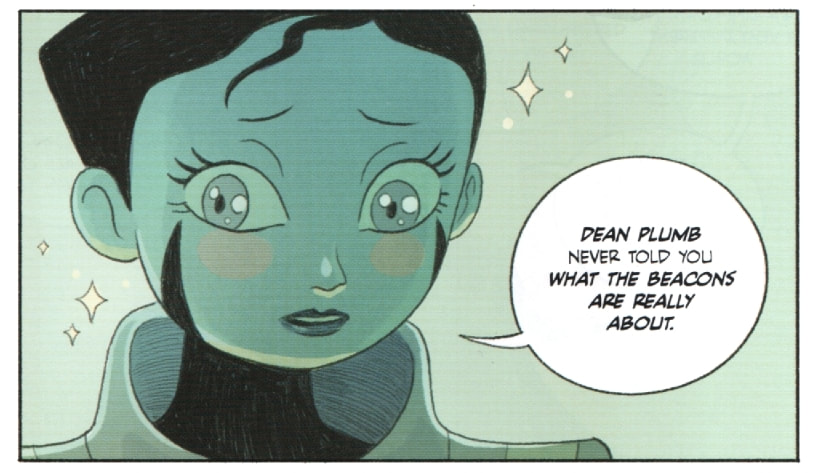

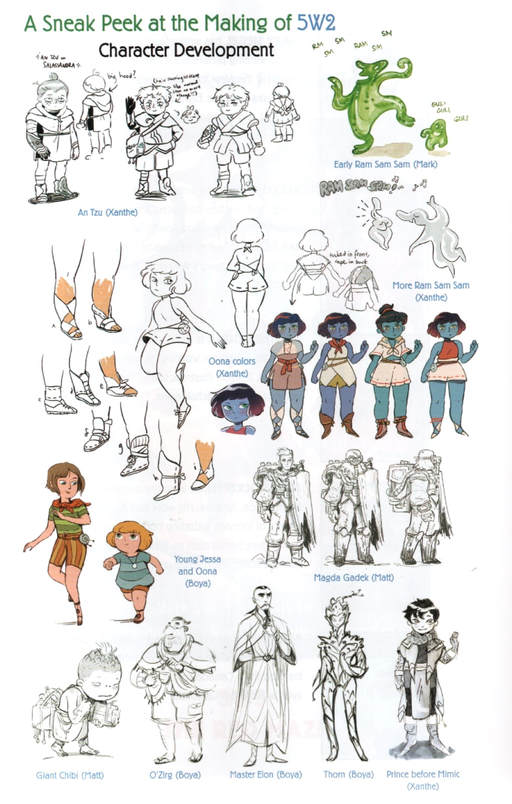

5 Worlds: The Red Maze. By Mark Siegel, Alexis Siegel, Xanthe Bouma, Matt Rockefeller, and Boya Sun. Random House, May 2019. Paperback: ISBN 978-1101935941, $12.99. Hardcover: ISBN 978-1101935927, $20.99. 256 pages. 5 Worlds — the epic science fantasy series by brothers Mark and Alexis Siegel and the artistic team of Xanthe Bouma, Matt Rockefeller, and Boya Sun — has been overstuffed with invented worlds, scenic wonders, and dizzying plot twists from the start (that being 2017’s The Sand Warrior and its 2018 followup, The Cobalt Prince). The series has bounded from one setup to another with a breathless energy and worked up a sprawling, spiraling plot. Its delights are many, but its confusions too, inspiring mixed reviews from yours truly (the first here, the second here). It’s a labor of love, obviously, and the complex collaboration behind it has wrought visually seamless results: a remarkable artistic and editorial feat. There have been times, though, when 5 Worlds has seemed to rush narratively from one thing to another: this world, and then that; a tip o’ the hat to this influence, then that one; another disclosure of tangled backstory, another "huh?" moment. I’ve sometimes wondered if the influences were going to cohere into something distinct, and if the long game wasn’t getting in the way of the individual volumes. But no longer. The recently-released third book, The Red Maze, gathers up, extends, and deepens 5 Worlds with confident character and thematic development, careful pacing, and a troubling relevance. It’s the strongest, most sure-handed of the three books to date, also the sharpest and most topical. An ambitious entry, it gains depth on rereading, while still pulling this reader eagerly on, toward the next volume. Now we’re talking. Briefly, 5 Worlds depicts a system of five planets (to be visited over the series’s five volumes) that are dying of heat death and can only be saved by the lighting of a series of ancient “Beacons,” one on each world. Each new volume of the series focuses on one of the worlds and uses an integrated color scheme implying the dominant culture(s) of that world. The protagonists, a classic heroic triad, are Oona, trained in the ancient discipline of “sand dancing,” who is tasked with reigniting the Beacons; An Tzu, a street urchin of unknown origins and powers, still coming into his own; and Jax, a sports star and (secretly) an android, though archly nicknamed “The Natural Boy.” Each has an unfolding origin story full of twists and surprises, from Oona’s true heritage (revealed in The Cobalt Prince) to the newfound humanity of the Pinocchio-like Jax (who was waylaid for most of the second book but returns and grows more complex here), to An Tzu’s “vanishing illness” (i.e. disappearing body parts) and newly discovered oracular powers. All three have nonstandard, stereotype-defying qualities and hail from vividly realized cultures (carefully imagined in terms of ethnicity and class). In The Red Maze, all three have arcs, problems, and discoveries, without any one of them being overshadowed by the others. From the book's opening, a frantic action scene that reintroduces Jax, to its final pages, which tease the forthcoming Volume Four, the plot rockets along, and yet, more so than in past volumes, makes room for quiet, character-building exchanges and epiphanies. The Red Maze made me want to reread all three volumes with an eye on that proverbial long game. If the second book improved on the first, this new volume overleaps them both. The Red Maze’s special power comes partly from its pointed political relevance. The book allegorizes the current politics of our world in a way that's pretty much on the nose, and crackles with urgency. At last, it seems that 5 Worlds is discovering (or perhaps I am just belatedly discovering?) its themes, which include, broadly speaking, fighting impending ecological disaster while speaking truth to power, and finding one’s identity in principled resistance without losing the joy of life. The Red Maze depicts its heroes saying "hell no" to the short-sightedness and greed of oligarchs and false populists who have vested interests in denying that anything is wrong. Along the way, of course, it tells multiple coming-of-age stories, as each of our three heroes has self-discoveries to make — but it's the constant backdrop of world-threatening climate change that sharpens everything and raises the stakes. This particular volume takes place on “the most technologically advanced of the Five Worlds,” the supposedly free and democratic Moon Yatta, against the background of, ah, an election campaign that pits the ordinary mendacity of a self-serving incumbent politician against the demonic scheming of a populist gazillionaire challenger, a demagogue boosted by authoritarian media and keen to exploit xenophobia. Both would like to silence our heroes’ message of looming environmental collapse. Basically, we’re dealing with climate change denial here, as well as a stew of political chicanery, nativism, and bigotry. Familiar? There’s more. The Yattan regime, we learn, suppresses a minority of protean “shapeshifters” who have the ability to change bodily form (and gender) but who are subdued by “form-lock” collars (clearly, signs of enslavement). Signs of oppression are everywhere, most obviously in a diverse crew of rebellious street kids who become an intriguing if perhaps under-developed new supporting cast. Despite the kids' help, though, our heroes' attempts to penetrate the industrial complex or “maze” around Moon Yatta’s Beacon come to nothing. So, desperate measures are called for. Jax, athletic superstar, is coopted to play in a much-hyped televised championship that becomes a propaganda coup for the challenger, supported by the obscenely wealthy “Stoak” brothers. And if all that doesn’t come through clearly enough, allegorically, consider this blurb on the book’s inside front cover: ...Moon Yatta is home to powerful corporations that have gradually gained economic control at home and on neighboring worlds... [Its] democratic system of government is widely admired in the Five Worlds, but there is increasing concern that it may be undermined by the political influence of its corporations. Indeed, a cabal of super-rich profiteers, aided by the rantings of a Limbaugh or Alex Jones-like media blowhard, works to undercut the Yattan democratic system. Everything, it seems, is about money, even health care: a hospital scene depicts a boastful, tech-savvy doctor determined to leech every penny from his patients. Other scenes show populist xenophobes towing the oligarchs’ line and condemning the shapeshifters for threatening the social order. Racism and homophobia are implicitly evoked (you have to read between the lines, but what’s there isn’t that hard to see). Unsympathetic readers might call this propaganda, but children's fiction, including fantasy fiction, has always been value-laden if not didactic. My description may make The Red Maze sound less like a story than a screed, but it actually is a story, and a thrilling one, a rattling good yarn. At its heart is a spiritual crisis for Oona: the weight of expectation on her is so great that it crushes her joy in dancing, in using her near-magical art. She falters, bewildered and panicked by the retreat of her powers. (This recalls, for me, Kiki’s temporary loss of confidence and magic in Miyazaki’s adaptation of Kiki’s Delivery Service.) Late in the book, a training sequence, that is, a mentor-mentee sequence, allows Oona — and the story — a calming and refocusing moment, a catching of breath. Thus Oona is able to take a perspective beyond that of the looming crisis, and learn a crucial new power. Her dilemma has to do with finding ways to sustain her spirit in the face of overwhelming environmental and political odds: how do you keep going when things are so terrible? That’s a kind of dilemma, and story, that needs telling right now. Oona's mentor Zelle (one of a long line of mentor or donor figures in 5 Worlds) tells her, “We each have our own red maze. We can be lost there.” What’s needed, Zelle suggests, is joy and inspiration: some delight in the doing, right now, whatever the odds against us. Oona, though, admits that she feels stuck “inside the red maze. I feel confused just thinking about the place.” She has to look for other perspectives on her task, other angles on the problem. Out of that crisis comes the through-line that gives The Red Maze its depth and integrity. This third volume of 5 Worlds makes everything click. It's aesthetically dazzling, of course; 5 Worlds has always been beautifully designed, rendered, and colored. The Red Maze is another master class in revved-up graphic storytelling, the pages at times bursting into frenzied action, during which bleeds, diagonals, and unframed figures spike the book's ordinarily measured and lucid delivery (dig, for instance, the ecstatic climax). The series has always been good at that sort of thing. Yet now 5 Worlds is jelling narratively and thematically. The Red Maze builds smartly on the previous books, and brings fresh nuances to its heroes, growing each into a deeper, more interesting character. The myriad artistic influences are still there, but the world-building no longer feels, say, stenciled from Miyazaki; instead the story-world has gained enough heft and momentum to draw this reader into its own singular orbit. And the stakes feel genuinely high. I expect that, when 5 Worlds is completed, rereading it all and watching it come together is going to be a very rewarding experience. Granted, The Red Maze won't make sense to those who haven't read the first two volumes: though 5 Worlds has a modular structure (one world per book), it is definitely one continuing story, not an episodic series. (Start with The Sand Warrior.) But this third volume is a terrific reward for those who've been following along: a timely, urgent, artfully layered adventure. I think we’re looking at some kind of monument in the making. Random House provided a review copy of this book.

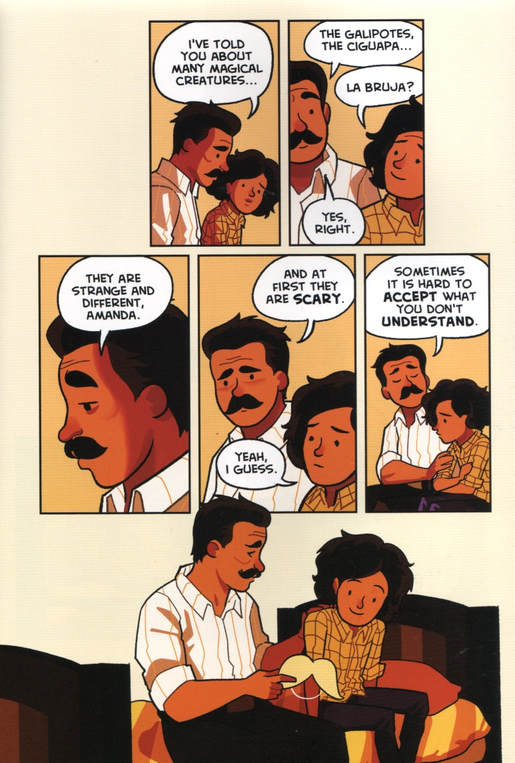

The Cardboard Kingdom. By Chad Sell, with Vid Alliger, Manuel Betancourt, Michael Cole, David Demeo, Jay Fuller, Cloud Jacobs, Kris Moore, Molly Muldoon, Barbara Perez Marquez, and Katie Schenkel. Alfred A. Knopf/Random House Children’s Books, June 2018. ISBN 978-1524719371. Hardcover, 288 pages, $20.99. The Cardboard Kingdom celebrates community and in fact is the work of a community: a team made up of cartoonist and creator Chad Sell and ten co-writers, referred to by the publisher as “new and diverse authors” (one of whom, Kris Moore, sadly seems to have passed away). An impressive collaborative feat, it depicts an idealized neighborhood of kids who also collaborate, turning their everyday lives into, basically, a nonstop live-action roleplaying game. A paean to shared creative play—essentially, the book is about kids as cosplayers, crafters, and friends—it must also have been a playful, if complicated, project. Happily, everything clicks. The book works as an anthology of short stories and vignettes, from about five to thirty-plus pages in length, but more powerfully as a novel, which, though episodic, designedly builds to a big and satisfying finish. Sell enlisted each author to write a story or two, and then apparently brought them together to cook up the boffo finale. Reading it straight through, it’s almost seamless; the novel builds its neighborhood carefully, gradually introducing new characters into its busy communal scenes. Though the publisher says The Cardboard Kingdom is about “sixteen kids,” I counted nineteen distinct, recurring child characters in the novel, some identified only by their roleplaying names, some known by more than one name. There’s a lot of juggling going on, but never to the point of distraction. The publisher also says that the book depicts “adolescent identity-searching and emotional growth”—yet it certainly isn’t YA fiction. My sense is that The Cardboard Kingdom is emphatically a middle-grade novel, aiming for upper elementary to perhaps middle school age. While its large cast, complex rigging, and lively and dynamic pages say “middle-grade” to me (not younger), its eager, almost ingratiating cartoon style reminds me of Pixar—say, Inside Out, with its mix of emotional gravity and toylike cuteness. Certainly the book depicts identity-searching and emotional growth; however, its bright cartooning, winsome children, and almost Peanuts-like sense of suburbia (not wholly idyllic like Schulz’s but still reassuringly safe) seem pre-adolescent in tone. Its let’s-pretend and DIY ethos brings back some early memories of my own. I mention this not because I’m concerned about age levels (KinderComics doesn’t usually focus on leveling) but because I’m interested in The Cardboard Kingdom’s treatment of identity, which I consider bold for a middle-grade novel. If graphically the book suggests years of reading Peanuts and Tintin, its imagined neighborhood has a utopian queer- and trans-positive vibe that would make it a good companion to, say, Alex Gino’s groundbreaking George (also a middle-grade fiction). Among the book’s young role-players are several who defy or ignore gender norms. In fact the first story, “The Sorceress,” written with Jay Fuller, introduces a cross-dressing pair: the titular Sorceress, soon shown to be (ostensibly) a boy but only much later identified as “Jack,” and his neighbor, a seeming girl who refuses the princess role and becomes The Knight (I don’t think she ever gets another name). Reportedly, this story was the kernel or inspiration for the whole book. There’s more: one character, Sophie, defies expectations of sweet girlishness and becomes a rampaging, Hulk-like bruiser she calls The Big Banshee; another, Amanda, a self-styled Mad Scientist, worries her father by wearing a mustache. Meanwhile, the relationship between Miguel the Rogue and Nate the Prince hints at a young gay crush. The Cardboard Kingdom, in fact, resists conventional gender and sexual roles throughout. For all that, it’s a story about kids who like to imagine combat: big, frenzied dust-ups between heroes and villains. Reading it, I was more than once reminded of an Avengers movie. If the drawing style and solid, bright colors follow a clear-line aesthetic, recalling the moral and ideological sureties of so many children’s comics, then Jack Kirby is surely a reference point too, from the Big Banshee’s unabashed monstrousness (more cheerful than tragic here) to the outrageous costuming, replete with spiky cardboard headgear that would do Cate Blanchett proud. The book taps the same vein of explosive fantasy that superhero comics do, but with more charm than most. The neighborhood kids of The Cardboard Kingdom, though they never really hurt one another, like to run around and fight; Sell and company are unafraid of children’s capacity to play at physical conflict and violence. Further, many of the kids like to be “bad guys” as well as “good,” and the book gleefully mines that tendency for humor. There’s a disarming mixture of sweetness and brutal imaginings in the book, though it all comes out seeming like harmless fun. Sell and his collaborators have a feel for the reckless, revved-up fantasy lives of young kids hanging out together--I appreciate that. And no adult ever dictates the terms of, or reins in, what the kids are fantasizing about. The book presents an entirely child-driven and child-centered world of cooperative, if pugnacious, play. In short, it’s feisty as well as sweet. Behind its bright, cheery surface, then, The Cardboard Kingdom is structurally tricky and thematically gutsy. On the critical side, I would say that some of its component stories resolve too quickly; the book runs the risk of being too neat, because its nested structure and sheer number of characters demand fast pacing, even when dealing with hard matters of identity and parent-child tension. Problems are invoked and solved with speed. In that sense, it’s, again, utopian. Also, the book makes some obvious, even heavy-handed, didactic moves, though in the direction of adult chaperones rather than child readers. Its sharpest lessons will likely be ones of forbearance and acceptance aimed at concerned parents whose children are behaving, well, unexpectedly. The best examples of parenting in The Cardboard Kingdom involve suspending or tempering judgment, i.e. being brave about children’s imaginative self-fashioning (would that all anxious parents course-corrected as readily as those in the book). But, most of all, it’s the book’s wise embrace of childhood play that makes The Cardboard Kingdom a brave and interesting graphic novel, one I highly recommend. Random House provided a review copy of this book.

NEWS! As I was reviewing 5 Worlds: The Cobalt Prince (see yesterday), I noticed, on the back cover, a logo that was new to me:  While Random House Children’s Books has already published a number of graphic novels, I hadn't seen this logo before. Today I learned why, as RHCB officially announced Random House Graphic as their new graphic novel imprint! Although Random House Graphic is not expected to launch until fall 2019—i.e. the first books developed specially for the imprint are not expected until then—Random House already appears to be telegraphing its intentions (though it's not clear exactly how RHCB's graphic novel backlist, including 5 Worlds, will mesh with the new imprint). A press release I received from RHCB this morning states that Random House Graphic will launch in fall 2019 with titles for children and teenagers and a combination of literary and commercial works. Random House Graphic will hire a team to be solely dedicated to the creation and promotion of the imprint’s titles, and for outreach and advocacy within the industry and direct-to-consumers to increase readership. The most exciting part of this news, to me, is that Gina Gagliano will be heading that team, as the new imprint's publishing director: Gagliano is a leading figure in children's and YA comics publishing. As part of the First Second team since that company's launch in 2005—most recently as First Second's Associate Director for Marketing and Publicity—Gagliano has been responsible for building connections between graphic novel publishing and diverse librarians, literary professionals, and teachers (myself included). A bittersweet note of parting on the First Second blog (from Mark Siegel, Editorial & Creative Director, and Calista Brill, Editorial Director) describes Gagliano as one of the "transformative factors" behind the "unfolding comics renaissance in America," and that's not just hype. Gina Gagliano has been a marketer-with-passion and a veritable force. Anyone who has spent even a little time talking with her has a sense of her expertise in children's literature, comics, and publishing. (Speaking personally, I'm a children's literature teacher of many years, but when I talk to Gina I feel like I should be taking notes, because her knowledge of that field is vast and detailed, and she often recommends books that I know little or nothing about.) First Second has been extremely fortunate to have Gagliano on its team, as she combines expertise in children's books with dedication to independent comics and the artist-driven side of comics culture. Her work as an event organizer (for the Brooklyn Book Festival, BookExpo, the Women in Comics collective, and the Toronto Comic Arts Festival) has made her a very respected figure in both mainstream and small-press publishing contexts. A fount of information and a tireless connector of people, Gagliano represents a living link between comics cultures and one of the best examples of a comics pro who has helped the graphic novel thrive in the book trade. In short, RHCB has made a wise choice. As publishing director of Random House Graphic, Gagliano will report to RHCB Senior Vice-President, Associate Publisher, Judith Haut. Quoted in the press release, Haut says, “It is a truly exciting and important time of growth for comics and graphic novels within the kids' market, and we see a distinct opportunity to reach even more readers. We are thrilled to have Gina, with her creativity, expertise, and passion for the medium, at the helm of our new venture.” Over at Publishers Weekly, Calvin Reid has full details. Here's a notable passage from Reid's article: ...Gagliano called it “too early” to specify the ultimate size of the list or the size of the staff she will assemble. But she emphasized that the imprint will hire "editors, designers, and publicists," and will focus on “all genres and all age categories. Kids need to grow up with graphic novels and publishers need to provide a complete reading experience. We need to add to the breadth of the comics medium in order to transform the U.S graphic novel market.” Hear, hear. I look forward to what Random House Graphic will bring.

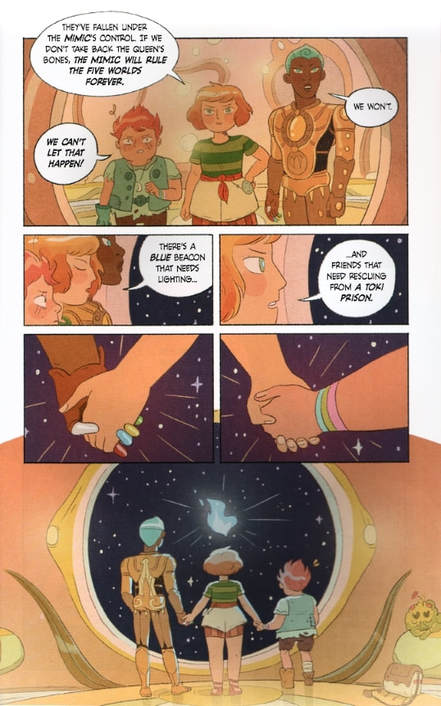

5 Worlds: The Cobalt Prince. By Mark Siegel, Alexis Siegel, Xanthe Bouma, Matt Rockefeller, and Boya Sun. Random House, May 2018. Paperback: ISBN 978-1101935910, $12.99. Hardcover: ISBN 978-1101935897, $20.99. 256 pages. Epic fantasy is a balancing act. On the one hand, its make-believe settings tend to be rule-governed and to strive after internal consistency, as if some kind of voluntary constraint were needed to hem in and discipline the pure exercise of fancy. We have to know that the characters, however magical, won't be able to do just anything they please, and that the worlds won't simply change in mid-story to suit the storyteller's whims (anyone who has ever played Dungeons & Dragons with a very whimsical DM knows how annoying that can be). Tolkien's Middle Earth has set a standard: that high fantasy worlds are to be approached with something like the self-discipline of historical fiction, even if that kind of discipline belies the very term fantasy. On the other hand, epic fantasy series, as they sprawl, often reveal new things about their worlds that shift the terms of our understanding. They elaborate, giving us more and more backstory that impinges on, or changes the stakes of, the story we're reading. Multi-volume fantasies, as they ravel out, tend to disclose (or discover) more about origins or antecedent conditions, uncovering deep foundations that may generate new problems. Even Tolkien, who crafted a history of Middle Earth before he publicly shared that world, famously said that The Lord of the Rings "grew in the telling," which I take it means that the book (ultimately trilogy) ended up drawing in more and more of the mythic backstory as he had privately envisioned it. Of course, there are also epic fantasy series written without the same strict dedication to consistency: say, Zelazny's Amber, with its odd, shifting rules. Such shifting or feinting may betray Tolkien's disciplined mode of high fantasy, but I confess I enjoy twisting, ramifying plots that reveal more of a world to me, even when the twists undermine what I thought I knew about the world at first. Consider the way Rowling's Harry Potter turns out to be a multigenerational saga set in a world more layered, and corrupt, than the first book shows, or the way Le Guin’s Earthsea, in its later books, dismantles its own patriarchal foundations, or the way Jeff Smith's Bone, in the seventh-inning stretch, gets more tangled and complex. In a satisfying fantasy epic, we will come to believe that all the complications were foreordained and fit perfectly. Besides self-consistency, then, I do enjoy the continual deepening of fantasy worlds. I bet a lot of readers do. As we travel the worlds, we learn, even as the heroes do, how complex the worlds truly are. That, I think, is the effect that 5 Worlds is going for. 5 Worlds, a collaborative graphic novel series that launched last year, does not quite persuade me that everything has been worked out, or that everything fits. Its cluster of worlds is complicated, even baroque, yet its plot is a breathless, rocket-propelled blur. I reviewed the first volume, The Sand Warrior, here recently, and complained that the tale suffered from tangled plotlines, a frantic pace, and too much downloading of mythic backstory. The second volume, The Cobalt Prince, is due out this week, and guess what? It has all those same qualities. The Cobalt Prince does not "solve" the "problems" of The Sand Warrior, and there are moments where its storytelling gets muddled. However, the book is splendidly imaginative, enough so to make its problems into virtues—which is to say that I'm glad to be revisiting 5 Worlds and exploring its universe. There's a lot going on here, plot-wise, and the book is a delirious exercise in graphic world-building. Thankfully, it remembers to round out and humanize its characters as it goes, and so attains a poignancy that the first volume lacked. If The Sand Warrior seemed promising, The Cobalt Prince is grand. By way of recap (here I'll crib from my first review), 5 Worlds is a science fantasy co-scripted and designed by cartoonist Mark Siegel and his brother Alexis Siegel and then further designed and drawn by three other cartoonists, Xanthe Bouma, Matt Rockefeller, and Boya Sun. Its plot revolves around an ecological catastrophe that threatens five rival yet interconnected planets. These are Mon Domani, the so-called Mother World, and her four satellites, each with a distinctly different culture. All five worlds are drying out and dying of heat death. Per an ancient prophecy, this disaster can be averted by relighting the long-dormant "Beacons” on each world, but not everyone believes the prophecy. Rivalry among the worlds gets in the way of cooperative problem-solving, and a shadowy adversary known as the Mimic (a sort of Dark Lord) exploits this rivalry in order to sow invasion and war. Our heroine Oona, an unfledged “sand dancer” of Mon Domani, seeks to relight the Beacons and stop the Mimic, with the help of a resourceful urchin named An Tzu and a sleek android called Jax. The first book centered on Mon Domani, but The Cobalt Prince moves on to other worlds: Toki, home of the despised, racially Othered "blue-skins," and Salassandra, home to diverse religious orders. Though Toki is the main theater of action, the plot caroms from place to place. When first I saw The Cobalt Prince, I noted Jax's absence from the cover—and sure enough Jax gets sidelined along the way, as if his story were one too many for this book. A plethora of new characters more than fills his space, and The Cobalt Prince becomes a roll call of unfamiliar names assigned to familiar archetypal roles: Master Elon, a mentor and outlaw; Ram Sam Sam, a cute ectoplasmic critter; O'Zirg, a shopkeeper; Anselka, a healer; and Magda, another mentor, this one a Master Yupa or Obi-Wan type who possesses essential knowledge. These figures become helpers or donors to our heroes (in folklorist Vladimir Propp's sense). They also bring new info, as, in good fantasy fashion, The Cobalt Prince dives into fresh elaborations and disclosures. So, even as this second book explains and solidifies things that happened in the first, it also changes the terms of the first, complicating what was already tricky. Along the way, it changes how we think of Oona (and how she thinks of herself) and makes Oona's sister Jessa, a morally ambiguous figure in the first book, into the linchpin of the plot. The sisterhood of Jessa and Oona turns out to be this book's core. Narratively, The Cobalt Prince, like The Sand Warrior before it, is a mixed bag. On the plus side, the book's elaborations are emotional as well as clever, giving it more gravity than its predecessor. Also, I like the way its plot presses on the issue of racism as both personal animus and systemic oppression. In this story, distrust and division are keyed to skin color and culture, and at times racist hatred or fear threatens to misdirect our heroes. The challenges of transcultural understanding lend the frenetic, pinballing story greater depth. However, some of that subtlety gets fumbled along the way to a grand finale: a gathering of forces that, in its rigging, reminds me of The Hobbit's Battle of Five Armies, though sadly it comes across less clearly. The book, finally, stacks up too many plot points at once. A frenzied fight between giant, godlike avatars is particularly confusing, as those beings are possessed first by one side, then by the other, blurring the action's meaning. I had to reread some pages two or three times to understand what was happening, to whom, and why. When I finally did "get" it, it was rather glorious, but on first reading I was a bit lost. An anticlimactic but necessary "epilogue" does the work of sorting things out and springboarding readers onward to the next volume. I know I'll be there, waiting to see what complications the plot delivers next. Like its predecessor, The Cobalt Prince is beautifully designed, drawn, and colored, a rapturous outpouring of images. The five-person 5 Worlds team continues to be a collaborative miracle. The book wears its visual influences on its sleeve: a temple scene on Salassandra recalls Moebius; a chase scene involving starships and an "escape pod" cannot help but evoke Star Wars. Miyazaki looms large: treks through a post-apocalyptic "wasteland" echo the opening of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, while the final battle invokes Princess Mononoke's giant Forest Spirit but also its sense of ecological renewal, as the dead wasteland blooms green again. 5 Worlds, then, is frankly an exercise in allusion and synthesis. The reason I not only tolerate but savor these familiar elements is that, against all odds, the 5 Worlds team makes everything seem of a piece visually. 5 Worlds continues to be a grand experiment that seems ever in danger of flying off the rails. I hope the books to come will slow down, find their feet narratively, and deliver their action more clearly. I look forward to seeing how the team's world-building and piling-up of ideas comes together as an epic whole. Will everything fit perfectly? Of course I can't say yet, but the journey is head-spinning. Random House provided a review copy of this book.

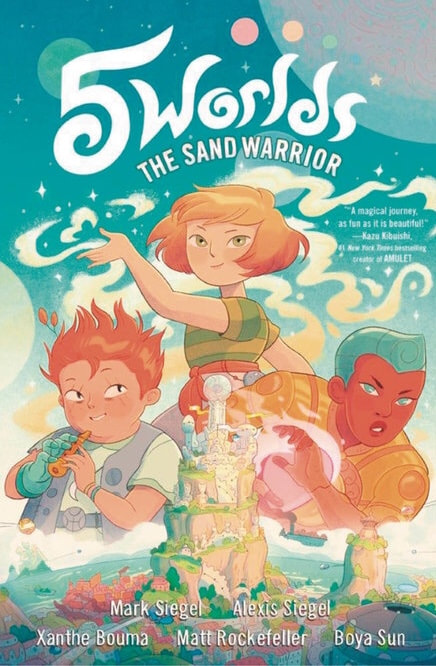

5 Worlds: The Sand Warrior. By Mark Siegel, Alexis Siegel, Xanthe Bouma, Matt Rockefeller, and Boya Sun. Random House, 2017. ISBN 978-1101935880. 256 pages, $16.99. A Junior Library Guild Selection. The Sand Warrior, a busy, fast-paced science fantasy adventure set in a wholly invented universe, teems with lovely ideas and designs. It is the first of a promised five-book series in the 5 Worlds (one book per world), and sets up a patchwork of different cultures, ecologies, technologies, and species. Indeed the book does some terrific world-building, the result of a complex collaborative process involving co-scriptwriters Mark Siegel and Alexis Siegel (brothers) and designer-illustrators Xanthe Bouma, Matt Rockefeller, and Boya Sun, working from an initial premise and designs by Mark Siegel. (Interestingly, Mark Siegel is founder and editorial director of First Second Books, but this is not a First Second title.) Reportedly, Mark Siegel conceived 5 Worlds as a project he would draw on his own (fans of Sailor Twain, To Dance, and his other books know that he could pull it off). However, as he and brother Alexis brainstormed the story, its plot and worlds grew so grand that he decided to turn it into a collaborative venture. Recruiting three recent graduates of the Maryland Institute College of Art — Bouma, Rockefeller, and Sun, who all met in a Character Design class at MICA — Siegel set in motion a complex, geographically dispersed teamwork, reportedly enabled by Google Drive, Skype or Zoom calls, texting, and secret Pinterest boards (see below for video links that shed light on this teamwork). The resulting book is remarkably consistent and aesthetically whole for such an elaborate process. It appears that Bouma, Rockefeller, and Sun became much more than hired illustrators on the project. They helped design and flesh out the worlds, and divided the page layouts and drawing (based on Mark Siegel’s thumbnails) in a selfless and seamless way. At the CALA festival last December, I bought a making-of zine (5W1 behind-the-scenes) from Bouma and Rockefeller, full of sketches and studies — a bit of archaeology for process geeks like me — and it intrigues me almost as much as the finished book. Visually, what has come out of that collaborative process is lovely. Story-wise, though, The Sand Warrior suffers from the greater ambitions of 5 Worlds. Its hectic, ricocheting plot zips forward too quickly for me to get a grip, even as it lurches into backstory with sudden, unexpected moments of info-dumping. Insertions here and there try to help the reader make sense of the 5 Worlds mythos (and do pay attention to the maps and legends on the endpapers). World-design and baiting-the-hook for future volumes get in the way of character development, even though the lead characters are soulful and troubled in promising ways. To be fair, there are moments of gravitas and emotional force amid the headlong action sequences, and there are consequential, irrevocable outcomes too. These impressed me. Yet I’d have liked to see longer spells of quietness, reflection, and clarity between the frenzied set pieces. The book actually does quietness rather well, but not enough; it has too much ground to cover. As a result, the plot comes off like a raw schematic of familiar things: prophecy, Chosen One, destiny, self-discovery, and reveals and reversals that I saw coming a long way off. When archetypal fantasy is stripped to its bones, too often the bones appear borrowed, and shopworn. It takes new textures to freshen those familiar elements. When the plot is streamlined to the point of frictionlessness (as in, for example, the breathless film adaptations of The Golden Compass and A Wrinkle in Time), we can all see that the game is rigged. My advice would be to slow down! Briefly, the plot of The Sand Warrior concerns the rival societies of five worlds: one great planet and her four satellites, each hosting a distinctly different culture. All five worlds are in crisis, dying of heat death and dehydration (a timely ecological allegory, ouch). According to an ancient prophecy, this catastrophe can be averted only by relighting the “Beacons” on each world, long since extinguished but still sources of wonder and controversy. Not everyone believes in this prophecy, and one world has plans of its own—prompted by the machinations of a dark, obscure adversary known only as the Mimic. Invasion and violence ensue. Our heroes, led by Oona, a mystically gifted yet diffident and halting “sand dancer,” seek to reignite the Beacon of their world and then defeat the Mimic. It’s all very complicated, with environmental and political workings and some of the plot machinery you'd expect to find in a fantasy epic with a prophesied hero. Bravely, The Sand Warrior tries to fill in all that detail on the fly; it foregoes the usual expository business of front-loading its mythos with a prologue, instead picking up backstory on the go. I appreciate that. However, this strategy poses challenges in terms of pacing and structure. Reading the book, I often felt as if I was being introduced to places and cultures just as they were being wrecked. The effect is like starting Harry Potter with the Battle of Hogwarts: too much too quickly, and with one or two familiar moves too many. By novel's end, even more interwoven secrets, and even more evidence of Oona's special nature, are hinted at—a touch too much—and the last pages almost desperately try to springboard into the coming second volume (out May 8). We close with obvious gestures toward self-realization and resolution but also toward open-endedness and further complication. Whew. Frankly, there’s too much to take in, and The Sand Warrior struggles to find a pace that is exciting but not skittish. Still, I look forward to further chapters in 5 Worlds. This five-headed collaborative beast, as frantic as its first outing may be, somehow has a single heart and speaks with a single voice. Sure, The Sand Warrior is overstuffed with known elements; the back matter acknowledges, among others, LeGuin, Bujold, and Moebius as inspirations, and many readers will also detect traces of Avatar: The Last Airbender and of Miyazaki (perhaps the beating heart of graphic fantasy nowadays). The story travels well-trod paths. But I like those paths; I like high fantasy. I also like the cultural complexity and diversity suggested by the book’s elaborate world-building. Further, the art attains a gorgeous fluency, with stunning color (reportedly Bouma did the key colors) and a lightness of touch, or delicacy of line, that recalls children’s bandes dessinées at their most ravishing. What’s more, the environments are transporting feats of design: giddy exercises in make-believe architecture and technology with a charming toy- or game-like density of detail. Naturally I want to stick around. I expect that The Sand Warrior will improve with rereading once more of 5 Worlds is revealed, and I look forward to seeing the characters through their troubles and gazing at whatever fresh landscapes they traverse along the way. In scope, and certainly in complexity of mythos, 5 Worlds compares well with Jeff Smith’s Bone — what it needs is patience, and pacing. Sources on the 5 Worlds Collaboration:

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed