|

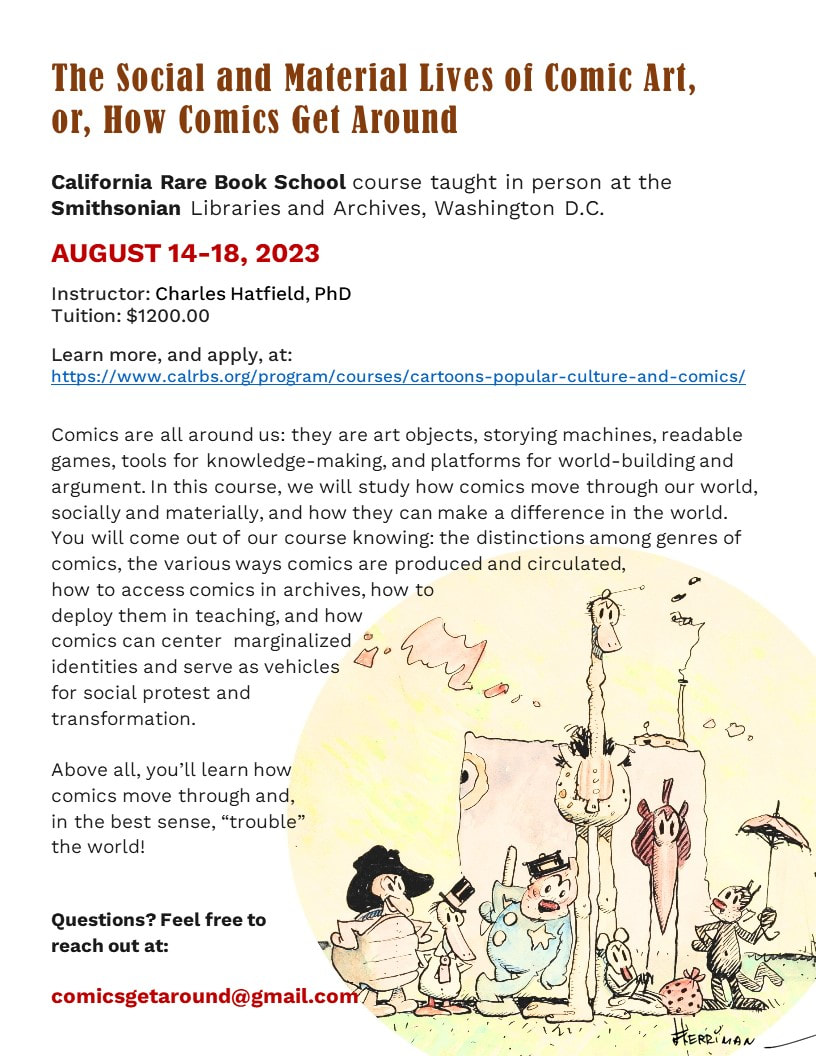

This summer, for the first time, I'm teaching a course for UCLA's California Rare Book School (CalRBS). Titled "The Social and Material Lives of Comic Art, or, How Comics Get Around," the course is part of a new partnership between CalRBS and the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives in Washington, D.C. I'm thrilled to be doing this! As I envision it, the course will be a hands-on workshop that will draw upon the Smithsonian, the Library of Congress, and other D.C.-area resources, involve several site visits or field trips, and bring in multiple guest speakers. If you'd like to know more about it, or would like to apply, visit: Popular yet personal, branded as trivial yet rich with meaning, comics are more than cultural scraps or leftovers. In fact, comics are everywhere: they are art objects, storying machines, readable games, tools for disseminating knowledge, and platforms for worldbuilding and political argument. Whether viewed as historical artifacts or distinctive literary and artistic works, comics carry culture with them. In this workshop, we will study how comics move through the world, socially and materially, how they can make a difference in the world, and how we, as teachers, researchers, and creators, can use them. Comic art has a complex social life. Comic books, graphic novels, strips, and cartoons come in varied material (and now digital) forms and reach diverse readerships. Many are thought to be ephemeral, as disposable as yesterday’s newspapers or tweets; some are built to last. Many last despite their seeming ephemerality, archived by collectors, fans, and, increasingly, archiving professionals and research libraries. Conserving, organizing, and accessing these artifacts can be a challenge but also a profound pleasure; comics offer us opportunities for creative engagement as well as deep research. Our workshop will study how comics come to be, how they circulate, where and how they are archived, and how we may teach with them. We will focus on comics’ physical materiality, on firsthand experience and “show and tell.” Our hands-on sessions will mix varied forms of nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first century comic art, from newspaper pages to comic magazines, from graphic novels to minicomix, zines, and webcomics. Drawing on the resources of the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives, we will explore the material and social histories of comics, the idiosyncrasies of comics production, including differences among American, European, and Japanese traditions, and how comics have been shored against time by collectors. We will consider comics as products of various industries, cultures, and social scenes—as historic artifacts, yes, but also urgent dispatches from the here and now. Participants will come out of this workshop knowing:

Do visit the CalRBS website, above, to find out more about requirements and credits! Also, please spread the word to anyone you think might be interested!

0 Comments

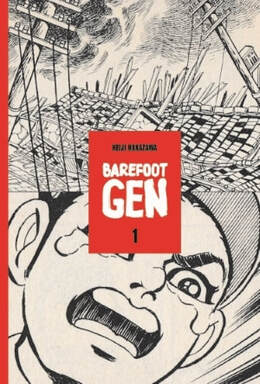

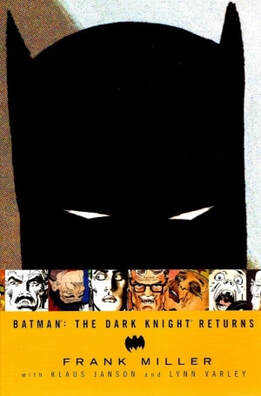

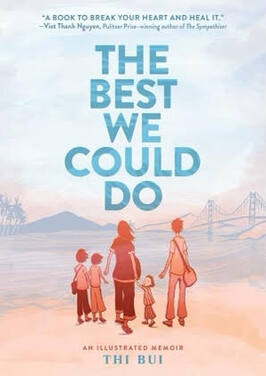

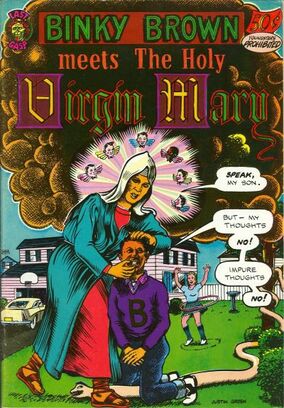

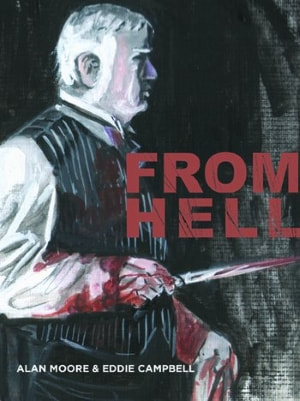

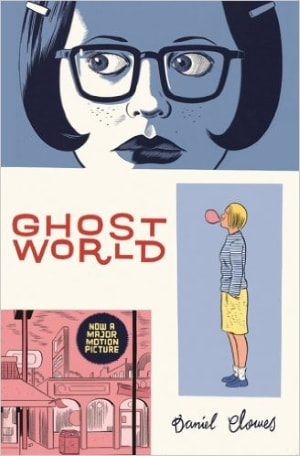

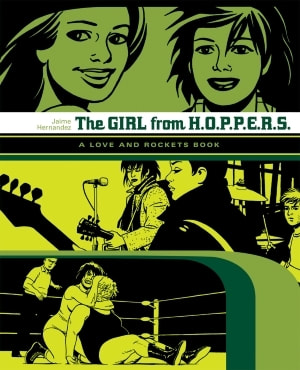

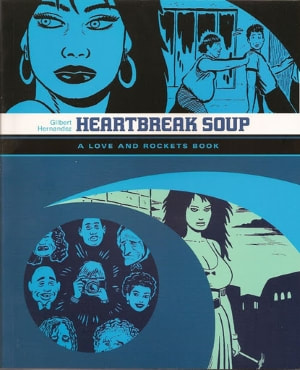

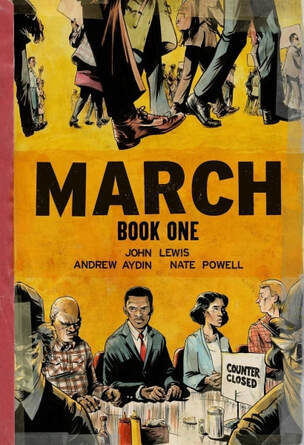

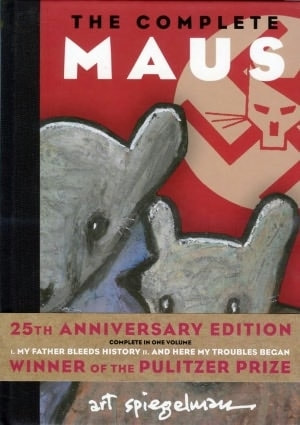

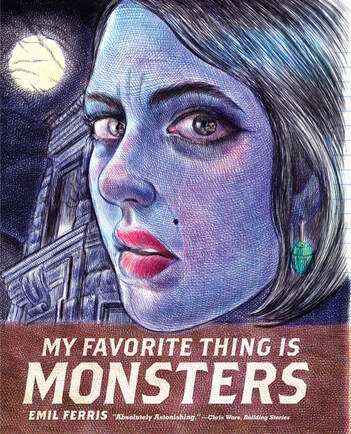

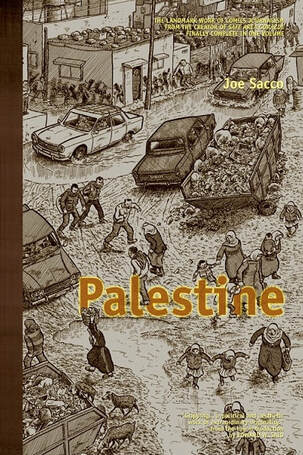

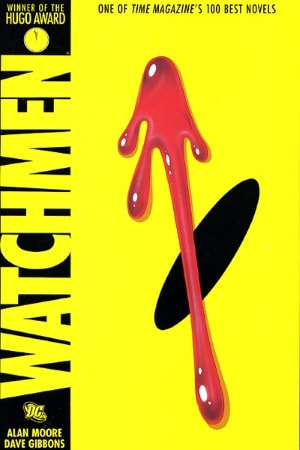

Foreword: As a teacher, I'm often asked to recommend graphic novels, or to explain where the graphic novel genre has "come from." What follows is a list I've used in order to field those questions, one copied, pasted, and adapted from a webpage I've maintained for various classes. Basically, the original aim of this list was to inform students briefly about much talked-about graphic books that we were not covering in class. It was designed to be a changeable document, a resource that could keep shifting and growing, and of course it by no means ever captured all the good and worthy books in the field; it's always been out of date, in fact. Lately I've begun to wonder if this list doesn't need to be drastically revised or perhaps this entire endeavor rethought, but I present it here as, perhaps, a first, rough guide. (Note that this list is not confined to children's and young adult comics.) Below are thirty-three especially noteworthy book-length comics in English. This is not a history of the graphic novel, but a sampling for convenience's sake. In assembling this “cheat sheet,” I've been guided not only by my own taste but also by the amount of scholarship and criticism these works have inspired. For the most part, the books listed here are touchstones for creators and critics; they represent genres or trends that are important in the field, as well as creators who have influenced others. That is, this list consists mostly of landmarks to which other graphic novels are often compared, and which have changed the way we talk about book-length comics. (That said, my own tastes and biases remain a factor, of course.) A bouquet of caveats: This list does not constitute a properly inclusive comics "canon." It is biased toward the self-contained literary graphic novel as practiced in anglophone North America, particularly the US. As such, it neglects a lot of important and delightful stuff — most of the comics world, in fact. I certainly don't claim that these are the only important comics out there, or even that these are the "most" important ones (actually, most great comics IMO are not graphic novels, but that's an argument for another day). Moreover, this list does not capture the present moment, that is, does not represent the range and diversity of comics these days (the newest books here are some three years old). Nor does this list do the important work of advocating for greater inclusivity in comics studies (a principle that informs my syllabi). But if you want to join conversations about the literary graphic novel as currently understood in English-language criticism, this list can give you a head start, a brief breakdown of some keystone titles. Just think of it as one possible point of entry, time-stamped 2020... PS. Clicking on a book's title will take you to an informational page maintained by its publisher. 100 Demons, by Lynda Barry (2002) Barry is one of the greatest writers in comics, and hugely influential. Whether writing, cartooning, or illustrating, she insists on composing everything by hand, and invites her readers into the process of composition — bodily, messy, human. This volume collects strips Barry did for Salon.com, and adds layers of collage and commentary; the result is an evocative storytelling scrapbook. Funny, haunting, troubling, these are memories of childhood and adolescence, transformed into what Barry calls “autobifictionalography.” Gender, culture, growing up, feeling different — all are reflected in Barry’s wonderfully loose, quirky style and intimate voice. An essential book in alternative and feminist comix. Alec: "The Years Have Pants", by Eddie Campbell (2009) Scots cartoonist Campbell found fame in the 1980s British small press with these autobiographical stories, thinly veiled by his use of an alter ego, “Alec MacGarry.” The Alec tales capture Campbell’s relationships and career over a span of decades, with a loose, gestural style and incisive, ironic, sometimes self-damning wit. From love, sex, and family life to Campbell’s take on the ever-changing comics world, these stories evoke the life and times of a brilliant artist and raconteur. They even chronicle Campbell’s work on From Hell (see below). The Years Have Pants gathers thirty years of Alec into one 640-page brick. American Born Chinese, by Gene Luen Yang (2006) This acclaimed and influential book — a key example of the graphic novel for young readers — has an unusual structure consisting of three ostensibly separate stories in different genres: fantasy, sitcom, and realistic, semi-autobiographical fiction. The interaction of these stories yields a whole greater than the sum of its parts, and speaks to issues of divided identity, as hinted by the title. Yang brings it all together unexpectedly, ingeniously, in ways that capture the dilemma of immigrants' children caught between cultures, desperate to transform and “fit in.” His accessible, cartoony, clear-line style evokes idealized childhood, belying the book’s darkness and complexity. The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye, by Sonny Liew (2015) Chan Hock Chye is Singapore’s greatest comics artist, and this book an exhibition of his works, interspersed with his biography, told in comics form. It’s also the history of Singapore itself, from decolonization (i.e. independence from Britain), to its separation from Malaysia, to the present. Here’s the catch: Chan Hock Chye is fictional, while his artistic influences — British, American, Japanese — are real-life landmarks of 20th century comic art. In this tour de force, Malaysian-born Singaporean artist Liew recasts the history of his nation as comics’ history, interweaving fact and fiction and probing the form’s colonial heritage. Provocative, brilliantly executed, mind-boggling. Asterios Polyp, by David Mazzucchelli (2009) This graphic novel by former Daredevil and Batman artist Mazzucchelli shows what can be done when every resource of the medium — layout, drawing style, colors, letterforms, balloons, everything — is deliberately varied to match different characters and shifting points of view. The story concerns architect Asterios — arrogant, out of touch — and his wife Hannah, and how their lives are transformed by circumstance. Mazzucchelli, one of the most electrifying talents in mainstream comic books in the 1980s, retreated from the limelight to explore alternative comics, then spent years crafting this layered masterpiece of form. Almost too clever, but also moving and beautiful. Barefoot Gen, by Keiji Nakazawa (1973-1987; translation completed in 2009) Gen, a semi-autobiographical tale, recounts Nakazawa's life as a survivor of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima — in ten volumes. It's a fierce, emotionally raw, yet deliberately crafted work: an intimate epic. Nakazawa depicts war, more particularly the Bomb, with brutal honesty, unquenchable anger, and a wounded heart. Gen makes a powerful dramatic argument for pacifism and anti-militarism, yet brims with violence, from large scale to small. A furious indictment of imperialism and warmongering (including Japan’s), this is searing, melodramatic, nakedly political storytelling — yet oddly hopeful too. A hugely influential autobiographical comic, and the first book of manga translated into English. Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, by Frank Miller, Klaus Janson, and Lynn Varley (1986) An aged, PTSD-haunted Batman comes out of retirement to save a dystopian Gotham; turns out he’s a righteous lunatic who insists on seeing the world in stark, uncompromising terms. This seminal Bat-story has influenced every Bat-movie and TV show made since the eighties, but it’s really in dialogue with the history of superhero comics and the comic book industry. Brash, brutal, Miller’s story runs roughshod over the DC Universe, bending the genre to personal and satirical purposes. Miller is unafraid to draw ugly to get the kind of intensity he wants — the result is an expressionistic nightmare. Forget the pointless sequels. The Best We Could Do, by Thi Bui (2017) Like several other books here, this memoir inhabits a genre made habitable by Spiegelman's Maus: the multigenerational family memoir woven out of war, atrocity, and trauma, informed by the author’s ambivalence toward her parents. Bui chronicles five generations of her family, first in Vietnam, then the US, all while examining her own resentments, fears, and complex, divided identity. Rigorously self-critical, artfully braided, and beautifully drawn in a fluid, brush-inking style, this book imparts a library’s worth of history, but also subtle, tangled feelings. Though familiar in its approach, it remains tonally and aesthetically distinct. A brilliant, gorgeous, revelatory autobiography. Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary, by Justin Green (1972) Binky stands in for author Green, and this comic recounts Binky/Green’s struggles with religious guilt and what he now recognizes as obsessive-compulsive disorder. An embarrassing, even harrowing memoir that reveals the author’s darkest secrets, this is also a beautifully crafted and hilarious high-water mark in the underground comix movement. It inspired Spiegelman’s Maus and the whole autobiographical comics genre. Weird, disturbing, and poignant, this comic still makes me laugh — and cringe with guilt every time I do. Green’s obsessive renderings, imaginative flights, and ironic humor about his own struggles have influenced comics ever since. Not for the fainthearted, but great. Blankets, by Craig Thompson (2003) Inspired by French artists, Thompson has a voluptuous, sensual style that carries readers away. Blankets is his breakout book, a memoir of adolescence, sexual awakening, and strict religious upbringing. Some readers find the heart of the book in its depictions of love and longing; I find it in Thompson’s rebellion against fundamentalism. This is not a memoir in the same vein as Green’s Binky; its images are more beautiful, its perspective less ironic, more Romantic, for some readers even mawkish. But read it to see how graphic memoir has been mainstreamed, and for a lovely example of the book as art object. Bone, by Jeff Smith (2004) Originally self-published, then republished by Scholastic, and now translated worldwide, Bone is a 1300-page epic (serialized over thirteen years). Smith has described it as Looney Tunes meets The Lord of the Rings, and his animation background comes out in the work, which combines Disneyesque charm and childlike heroes with unexpected depths. Smith’s style, influenced by Walt Kelly (Pogo), mixes slapstick cartooning with elegant brushwork and lush landscapes. His comic timing is terrific. The usual tropes of fantasy are here (princesses, dragons, dark lord, prophecy), but freshly redone for comics. Smith’s influence, particularly on children’s comics, would be hard to overstate. Building Stories, by Chris Ware (2012) The formalist comics achievement of the 21st century, so far? Depending on your POV, Building Stories either perfectly fulfills or violates the notion of “graphic novels.” It consists of a large box that recalls board games like Monopoly but contains fourteen different “Books, Booklets, Magazines, Newspapers, and Pamphlets” that can be read in any order (I don’t know any two readers who’ve read it the same way). The drama — poignant, sometimes heartbreaking — centers on a Chicago apartment building and a lonely, unnamed woman as she grows up and has a family. Ware captures sensations I never expected comics to capture. A Contract with God, by Will Eisner (1978) Veteran artist Eisner, a comics pioneer since the 1930s, launched his career’s last great phase with this “graphic novel” — actually four short stories about working-class Jewish lives, rooted in a common locale, a Bronx neighborhood remembered from Eisner’s youth. These stories mix social realism and melodrama. Here Eisner put his mature style — loose, rumpled, gritty — to new use, adopting a literary aesthetic and book format that lent legitimacy to the emerging graphic novel genre. Most impressive is the semi-autobiographical title story, a fable inspired by the death of Eisner’s daughter. Often wrongly called the “first” graphic novel, yet still seminal. Epileptic, by David B. (1996-2003, complete English trans. 2005) Another memoir whose brutal candor recalls Maus, Epileptic recounts the author’s family’s struggle to heal his brother’s severe epilepsy, which gradually isolates the brother and chokes off any chance of autonomous living. The family seeks cures in pseudoscience and mysticism, but is thwarted time and again, and haunted by its powerlessness. Concurrently, the book unfolds a history of postwar France, and 20th century atrocities generally, as the author-protagonist processes the world through a filter of rage and his art fearfully evokes an epileptic’s loss of control. Dark, hallucinatory, symbolically dense, swirling with hypnotic detail—a troubling masterpiece of graphic expressionism. From Hell, by Alan Moore & Eddie Campbell (1999) A fair candidate for Moore’s “other” great graphic novel (after Watchmen): a dense, paranoid retelling of the “Jack the Ripper” killings in London circa 1888, here treated as part of an occult conspiracy and an indictment of Victorian misogyny and classism. This project took a decade to complete, and shows not only Moore’s obsessiveness but also artist Campbell’s sense of period. Architecture, medicine, politics, freemasonry — it all gets caught up in their web. Campbell’s inky, scratchy, black-on-white pages, influenced by penny dreadfuls, are far from Watchmen's slickness. Magisterial, sinister, frightening, with alarming violence and butchery, and brutal commentary on gender. Fun Home, by Alison Bechdel (2006) Bechdel, known for her strip Dykes to Watch Out for, shifted gears with this memoir, which quickly became one of the US’s most-analyzed comics. Fun Home explores the relationship between Alison (an out lesbian) and her father Bruce (gay, closeted), whose death shortly after her coming-out may have been a suicide. The learned Bechdels often communicated through reading and writing rather than face to face, so Fun Home deploys myriad literary references (Joyce, Proust, Wilde, Colette, Fitzgerald) to weave an ambivalent portrait — precise, detailed, self-reflexive, darkly funny — of a complex, difficult man. After Maus, the most academically influential graphic book. Ghost World, by Daniel Clowes (1997) Drawn from Clowes’s comic book Eightball, Ghost World epitomizes mid-nineties alternative comics. A fiction with veiled autobiographical elements, it tracks the relationship between two young women, Enid and Becky, and what happens when they discover that their hip air of contempt for the world is not enough to carry them over the threshold to adulthood. Clowes’s satirical, deadpan humor runs throughout — the book is at times hilarious — but is matched by tacit emotional undercurrents. Beneath a chill, almost antiseptic style (emphasized by cold blue-green shading), Ghost World hints at psychological unease and turmoil, and ultimately tells a moving coming-of-age story. The Girl from H.O.P.P.E.R.S., by Jaime Hernandez (2007) The Hernandez brothers’ Love and Rockets (1981-) is arguably the most groundbreaking US comic book series of the past forty years. It defined alternative comics with its diverse cast, Latina/o and LGBTQ characters, punk rock/DIY ethos, mixture of underground and mainstream aesthetics, and experiments in form. Jaime’s “Locas” serial, based in Hoppers, a barrio inspired by his childhood in Oxnard, follows the lives and loves of Maggie Chascarillo and her circle, and is still going strong today. This volume captures Jaime’s amazing artistic growth in the mid-eighties, and boasts fluent, elegant cartooning, vivid, indelible characters, and searching, deeply moving stories. Heartbreak Soup, by Gilbert Hernandez (2007) While Jaime Hernandez was doing “Locas,” brother Gilbert created the other acclaimed serial in Love and Rockets: the stories of Palomar, a mythical Central American village populated by families, friends, lovers, and rivals. Gilbert’s style, broader and more grotesque than Jaime’s elegant naturalism, perfectly fits this magic-realist chronicle of love, loss, jealousy, psychological trauma, and social and political upheaval. This is bold work, exploring queer identities and sexualities, fearlessly depicting childhood and the traumas of growing up, and reflecting on art’s role in the world. This volume collects an extraordinary mid-80s run that shows Gilbert growing by leaps and bounds. Hicksville, by Dylan Horrocks (1998) Hicksville is a bucolic New Zealand town where everyone lives and breathes comics: a utopia for comics lovers. But what happens when a journalist comes to town determined to unearth the secret of a millionaire artist from Hicksville, a hometown boy turned pariah? Horrocks’ love letter to comic art is also a lament for the history of the comics business, one that has treated its artists like dirt. This funny yet melancholy meta-comic epitomizes alternative comics, and reflects on artistry-versus-commerce, the very nature of the comics form, and New Zealand's colonial history. Brilliantly cartooned: crisp yet scruffy, lively, organic. I Never Liked You, by Chester Brown (1994) A guilt-haunted memoir of adolescence, this book treats the ordinary stuff of high school relationships with a seriousness and graphic austerity that make it emotionally wrenching. Chester, a severely repressed young man, cannot seem to perform masculinity in the expected way, and his social relationships are punctuated by moments of almost-autistic withdrawal. His relationship with his mother is particularly fraught, and leads to a shattering climax. Beautifully drawn, with a fragile, minimalist line and dreamlike emotional reserve. A seminal example of graphic memoir from early-nineties comic books, and a key work of Canadian alternative comics from a restless, controversial creator. Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth, by Chris Ware (2000) Ware may be the most acclaimed cartoonist of the 21st century. He is famed for his command of, and willingness to push, the comics form; his dense, blueprint-like pages; his unerring, diagram-like style; the bleak honesty of his stories; and his focus on sad, isolated characters. He is comics’ poet laureate of loneliness. Some find Ware’s work unlovable, but others find in it a poignancy that few comics have reached. Jimmy Corrigan, his breakout novel, is a multi-generational chronicle of the screwed-up Corrigan family, and a devastating portrayal of failed, self-deluding White masculinity. Quiet, heartrending, epic, anticipating Ware's Building Stories. Kindred, by Damian Duffy and John Jennings (2017) Octavia Butler’s time-travel novel Kindred (1979) transports a modern African American woman to Maryland in the early 1800s, during slavery’s reign, where she must try to save the lives of her ancestors, both Black and White. Butler evokes the culture and psychology of slavery with horrific clarity. Duffy and Jennings wrestle with this challenging classic in an adaptation that favors frenzied expressionism over naturalistic detail, while seeking to preserve the original’s pacing and depth. The results show signs of struggle and inspiration, and intense feeling. A watershed in the contemporary Black comics movement, this has opened doors to new work. March, by John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell (three volumes, 2013-2016) Adapted from the memoirs of Civil Rights activist John Lewis (Freedom Rider, onetime chair of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and longtime Congressman), this trilogy is a testament: a personal window onto a history at once traumatic and exhilarating. While unfolding Lewis’s personal story, the book shows, clearly and unblinkingly, the politics and process of nonviolent Civil Rights protest. Powell’s organic drawing sets the rhythms, conjures a full, believable world, and brings the pages to life with an assured naturalism and graphic fluency that recall (without mimicking) Will Eisner. An autobiographical American epic, and an eye-opening work of comics historiography. Maus, by Art Spiegelman (two volumes, 1986 and 1991) Maus evokes the Holocaust from one survivor’s perspective—and that of his son, cartoonist Spiegelman, who works to get his father’s memories down on paper. It contains stories inside of stories, tracing the Shoah from prewar Poland to its still-traumatic aftereffects today, all while exploring the antagonism between father and son. Oddly, it exploits the so-called funny animal tradition: Jewish people appear as mice, Nazis as cats: a startling, sacrilegious device. Academically and critically, Maus has become America’s most talked-about book of comics ever: a generative project that inspired other books on this list. Its influence is hard to overstate. My Favorite Thing Is Monsters, by Emil Ferris (2017) Karen, a lonesome queer girl who envisions herself as a monster, investigates the death of an neighbor in her Chicago apartment building. That neighbor turns out to have been a Holocaust survivor with a knotted, complicated past. Karen's detective work brings her to dark places, and Ferris renders her quest in stunning art, lovingly detailed, obsessively dense, drawn almost entirely with a ballpoint pen in a series of spiral school notebooks (Karen's journals). Atmospheric, laced with references to high art and monster movies, suspenseful, and affecting, this staggering book does things with a comics page that I hadn’t seen before. Palestine, by Joe Sacco (1996) Journalist Joe Sacco makes comics about war zones and contested places in the world: Bosnia, Chechnya, the Middle East. These comics draw from his travels and investigative reporting. Influenced by underground comix, Sacco at first favored satire and grotesque exaggeration, but with Palestine, his foray into the Occupied Territories, he began shifting toward hyper-detailed realism, as he pursued his subjects with greater journalistic seriousness. Palestine advocates the Palestinian cause, giving an unabashedly political, while also scrupulous, unflinching, and human, perspective on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Sacco’s work has earned praise as both reportage and literature and fueled the graphic journalism movement. Persepolis, by Marjane Satrapi (2000-2003, English trans. 2003-2004) Persepolis, an Iranian autobiography first published in France, joins Maus and Fun Home as one of the most acclaimed graphic memoirs. Satrapi, born into a progressive Persian family, grew up during the Iranian Revolution and ensuing Iran-Iraq War. Her family, opposed to the Shah, welcomed revolution, but found the new fundamentalist regime even more oppressive. Satrapi left Iran for France. Using a stark, pared-down style, and an ironic voice that filters politics and violence through a child’s perspective, Persepolis explores traumatic memories and the bitterness of exile, while countering anti-Iranian stereotypes. Widely translated; adapted to film (2007) by Satrapi herself. Smile, by Raina Telgemeier (2010) Telgemeier, America’s best-selling graphic novelist, has legions of readers, especially girls aged 8 to 12. In 2019, her new graphic novel Guts (her ninth) got a million-copy print run. She started in self-published minicomics, but hit big with Scholastic, for whom she adapted four of Ann Martin’s Baby-sitters Club novels (2006-2008) before undertaking original GNs, starting with this memoir of girlhood, growth, and, um, dentistry. Phenomenally successful, Smile opened the door to further books by Telgemeier, both autobiographical (Sisters, 2014; Guts) and fictional (Drama, 2012; Ghosts, 2016). Accessible, energetic, crystal-clear, her work has become THE template for middle-grade GNs. Soldier's Heart, by Carol Tyler (2015) First published as a trilogy titled You’ll Never Know (2009-2012), Soldier’s Heart is now available in a single, revised volume. It tells the story of WW2 veteran Chuck Tyler and of his daughter Carol’s efforts to understand the War’s impact on his psyche. Working in the tradition of Maus, this intergenerational memoir digs into repressed wartime memories in order to understand and pay homage to a distant, sometimes irascible man whose hard exterior hides the aftereffects of trauma. Exquisitely illustrated in flowing, textured drawings and ravishing washes of color, this is a gorgeous, moving, heartfelt exploration of family (and) history. This One Summer, by Mariko Tamaki and Jillian Tamaki (2014) In this acclaimed Young Adult graphic novel, a girl, Rose, spends summer at the beach with her parents and her friend Windy. Rose’s mother, depressed, bears a secret that weighs on the family, Rose’s parents are at odds, and Rose blames her mom for the conflict. Windy and her family provide contrast. Rose, seeing through eyes clouded with mistrust and jealousy, tries to understand what’s expected of her as a woman, and what’s wrong with mom. A subtle exploration of girlhood and gender expectations, poetic in its rhythms and imagery. Transporting, haunting, a benchmark for its genre, though often unfairly maligned as "not for children." Understanding Comics, by Scott McCloud (1993) A book of theory presented in comics form, Understanding Comics may be the most-cited textbook in the field — but no textbook should be this much fun to read. Using his own cartooning as evidence, McCloud strives to build a grand theory that encompasses nearly everything about comic form: drawing style, breakdown/transitions, image/text interplay, line, color, on and on. It’s a terrific, insanely ambitious performance, one that has influenced comics studies ever since. To be honest, it changed my life, though nowadays I find myself arguing with it! The best candidate for a “primer” in comics studies. (We'll sample in class.) Watchmen, by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons (1987)

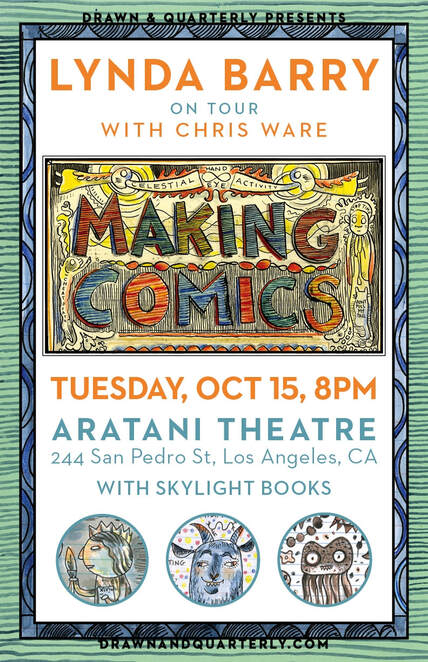

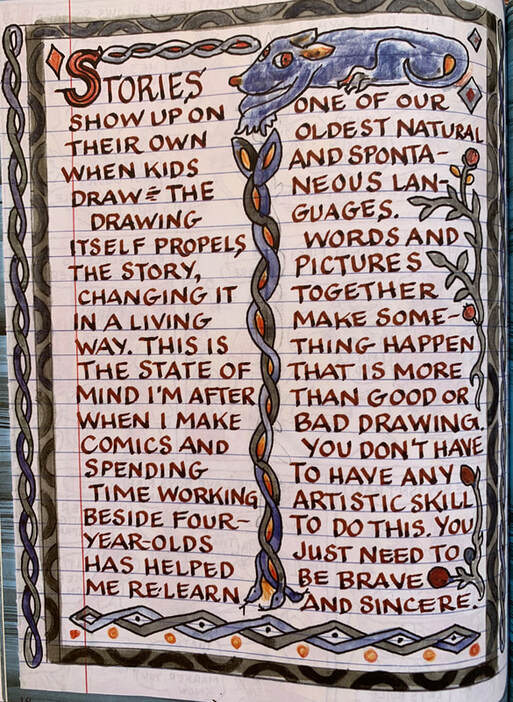

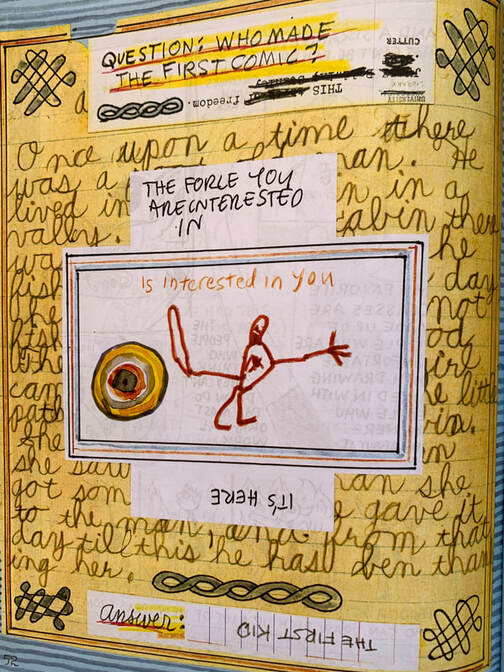

This most acclaimed of superhero comics asks, what would superheroes be like in the real world? Set in an alternate 1985, it’s a dystopian philosophical novel about the Cold War, empire, surveillance, paranoia, and fate. Obsessively detailed, Watchmen epitomizes the idea of the graphic novel as a system: dense, complex, full of echoes. Gibbons’s meticulous art perfectly captures scriptwriter Moore’s thirst for order. This book persuaded many that a superhero story could be Literature. (Forget the comic book spinoffs and movie, and take the 2019 TV series on its own terms; Watchmen’s meaning resides in its readability and book form.) Tuesday night’s conversation between Lynda Barry and Chris Ware (at the Aratani Theater in downtown Los Angeles, organized by Skylight Books) touched on childhood again and again. Both artists shared pictures or artifacts from their childhoods and recounted formative childhood experiences: Ware recalled a life-changing friendship he had as a young boy with another introverted, comics-loving schoolboy, memories of which continue to fuel his work (particularly his new graphic novel, Rusty Brown). Barry expressed her delight at working with four-year-old artists as well as university students, and evoked her girlhood experience of watching a troubled young uncle draw obsessively (a story movingly told in her new book, Making Comics). Both artists stressed honesty and spontaneity over scripting or planning, and invoked the unselfconscious narrative drawing of children as an inspiration. Barry, animated, disarming, and often hilarious (as ever), showed photos and videos of young kids drawing and learning, her comments suggesting an almost Wordsworthian romantic regard for children’s untrammeled creativity (though mixed with a matter-of-fact acceptance of the terrors that kids’ stories so often uncover). Ware, woefully self-deprecating (as usual) but also articulate and funny (as usual), spoke of memory, of reinhabiting remembered spaces and using comics to move through recollected time. It was one hell of a chat. Ware began his comments by recalling how Barry inspired him, early on. He was clearly in awe of Barry and delighted by her irrepressibility. Barry readily drew him (and the audience) out, and into deep conversation. Aesthetically, the two artists would seem an odd match, and frankly I think their works differ fundamentally despite the mutual admiration they projected during their talk, but as a conversational tag team they were delightful. The evening gave me a lot to think about—most of all comics’ debt to memory and the mysteries of narrative drawing. (I only regret that we couldn’t spend hours hanging around afterward, sharing our impressions of the talk with some of the many fans and artists there--a big and enthusiastic crowd. I think there were several people in the audience that I know, but we couldn’t seek them out, as the night was wearing on and we had an early morning to get ready for.) Though Ware’s comments about spontaneity in writing and drawing resonated with Barry’s, I confess I don’t see him working in anything like the same vein. He says that these days he works from page to page, instinctively, without script, but some architectonic notion of form still seems to guide him, and his work remains compulsively crafted in ways that veer far from what Barry celebrates in Making Comics. Indeed, Ware invoked as points of reference, or aspirational guides, such designing literary figures as Joyce and Nabokov, and expressed his admiration for big books that “sprawl” (but that also, I would add, impose global structure through myriad devices). His comments revealed how Rusty Brown is deliberately shaped with an overall sense of form: at one point he likened his new book’s structure to that of a water molecule, or a snowflake forming, and explained how the book’s removable jacket, which charts or anticipates the various narratives contained within, would be complemented by another such jacket when, years from now, he completes the novel’s anticipated second volume (!). So, he is already thinking about design conceits that will contain and contextualize whatever he comes up with. In light of comments like these, I take Ware’s comments about spontaneous invention with the proverbial grain of salt—I don’t think his meticulously crafted surfaces jibe with Barry’s ethos of unlocking creativity through drawing-as-process. I also think that Barry’s theorizing about narrative drawing (“There was a time when drawing and writing were not separated for you”) is really onto something, whereas Ware’s theories about narrative drawing often seem belied by the nature of his own work. For example, when Ware says that the functionality of a drawing matters more than its beauty or polish, I don’t see that borne out by his (often gorgeous, always pristine) pages, and I know many readers fetishize Ware's craft. Yet when Barry says similar things, I see a clear connection between her theory and her pedagogical practice (though I find her pages just as beautiful, in a much different way). In general, I tend to take Ware’s theoretical positions as somewhat at odds with what I see in his work, but Barry, I think, has truly embraced a romantic position about cartooning as demotic and open to all (“You don’t have to have any artistic skill to do this. You just need to be brave and sincere”). The obvious contrast between their respective styles of work, however, did not stop them from finding points to share and admire. Again, Ware seemed grateful to be sharing a stage with Barry, and, I thought, caught some of her energy, while Barry was, in effect, a gracious and delightful host. Despite the manifest differences between their work, I was fascinated to see both of them harking back to childhood as a wellspring of inspiration. They did this in different ways, of course. When asked by an audience member what they would say to their childhood selves if they could go back in time, they had very different answers: Barry said she would assure her younger self that it would all work out fine, that the struggles would definitely turn out to be “worth it." Ware, on the other hand, said he didn’t think he could reassure his younger self because, essentially, his work feeds on sad and anxious memories—that is, reassurance would take away the impetus or subject matter of much of his art. That right there speaks volumes, I think, about their differences in temperament and focus. PS. I’ve been reading Barry’s Making Comics with great interest and hope to review it here. It’s an extraordinary book, one that will influence my teaching going forward (as indeed some of Barry’s previous books already have). This is turning out to be an incredible season for new comics releases!

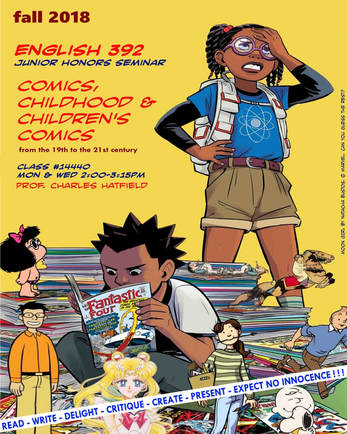

(The following statement opens the syllabus for English 392: Comics, Childhood, and Children's Comics, a course I am now teaching at CSU Northridge. English 392 launched on August 27, 2018, and we are at, roughly, mid-term. Regular KinderComics readers will recognize this post as one in a continuing series on teaching.) Did you know that Scholastic—publisher of Harry Potter, Captain Underpants, and The Baby-sitters Club—is also America's number one publisher of new, English-language comics? Not Marvel. Not DC. Scholastic. In fact, we are in a Golden Age of comics for children and young adults, in the form of the graphic novel. For about the past decade, graphic novels have been booming as a young reader's genre. Today, diverse publishers and imprints are competing to put graphic novels in the hands of children and teens: Graphix (Scholastic), First Second (Macmillan), Amulet (Abrams), Random House, TOON Books, Papercutz, BOOM! Studios, Farrar, Straus and Giroux BYR, Flying Eye Books (Nobrow), and others, including brand-new or forthcoming imprints CubHouse (Lion Forge), Yen Press JY, and even DC's soon-to-launch DC Zoom and DC Ink. In short, something interesting is going on. Who could have predicted this trend fifteen years ago? Comics, historically, have been a disreputable medium, branded as "objectionable," even as a threat to childhood, learning, and literacy. Further, the field of academic children's literature criticism (launched in the 1970s) has been so averse to comics that for decades it downplayed or ignored the form. The current interdisciplinary field of childhood studies has produced little work on comics. Even the field of comics studies, which has been exploding in the twenty-first century, has been so eager to attain legitimacy and "adulthood" (in terms defined by adult literature) that it has stinted research on children’s comics. Until quite recently, few scholars have felt the need to examine the intersection of comics and childhood. Yet comics have been central to the literacy stories, and reading lives, of millions of children the world over. Moreover, children's comics include many of the most influential comics ever published. Young readers have been the target audience of the most successful comics ever made—and those have been very successful indeed, in terms of profit, cultural influence, and deep connections made with readers. Comics for children are not new, even if we are now thinking of them in new ways. Many national cultures, from the Americas to Europe to Asia, have sustained long traditions of children's comics and drawn iconic images and characters from those comics (How can one understand postwar Japan without the manga of Tezuka, or contemporary France without Asterix?). In the United States, millions of readers young and old read comic strips in newspapers throughout most of the twentieth century, and the comic book, born in the Depression era, mushroomed by the end of the forties into an industry that sold tens of millions of magazines every month, most of them to young people. If comic books were disreputable, they were also hugely popular and influential. If many of us have almost forgotten that era, still it lives on, implicitly, in today's conversations about the graphic novel and children. Nowadays we see in comics the seed of a new visual literacy, complex and multimodal, but have the old fears gone away? Simply put, comics for children is a vital but still-obscured topic crying out for critical study—and that's what our English 392 class is all about. We will study the contemporary graphic novel as a children's and YA publishing phenomenon, and trace how and why this renascence has come about. In addition, we will consider (though alas only too briefly) the troubled history that lies behind this trend. What social, cultural, and educational changes have transformed the once-disreputable comic book into the graphic novel of today? What dynamics of power and cultural legitimization (or delegitimization) have changed the status of comics in our culture? To what extent has comics' reputation as illegitimate persisted, despite the current boom in children's comics? Together we will read articles and book chapters in children’s literature and comics studies, plus a range of children’s comics, from pioneering strips (e.g. Peanuts) to comic books to, most especially, contemporary graphic novels by authors such as Raina Telgemeier and Gene Luen Yang. As we work together, each of you individually will be able to find your own areas of interest and dig more deeply. Expect to present in class, i.e. lead class discussion, at least once during the semester; to pursue self-directed research responsive to your own interests; and to craft a final seminar paper roughly 10 to 12 pages in length. Expect several guest speakers as well!

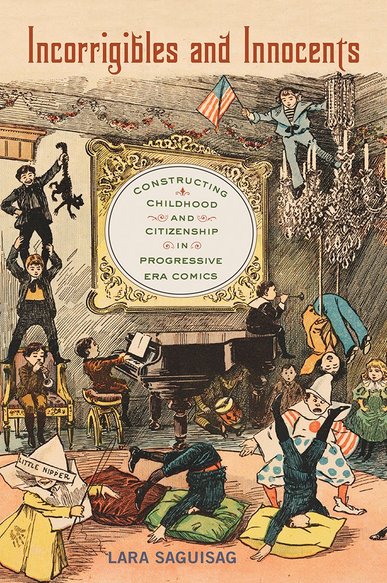

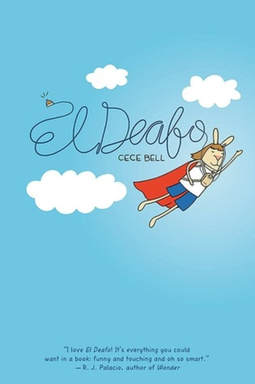

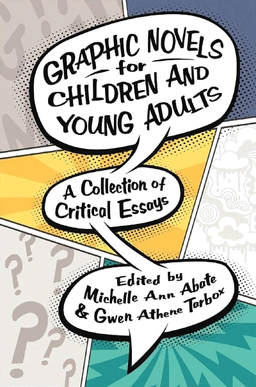

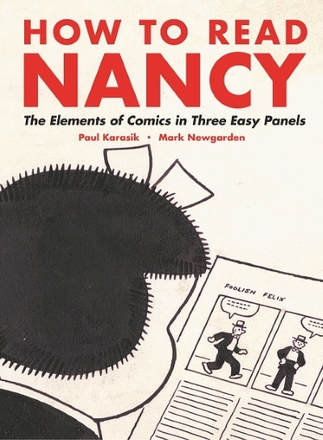

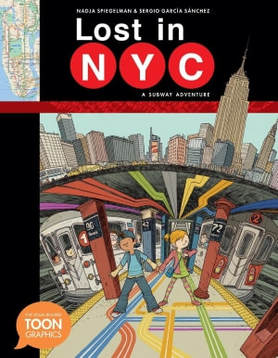

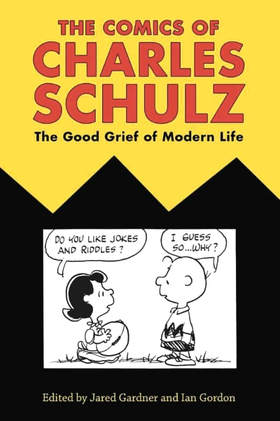

Sigh. About eleven weeks ago, I announced that KinderComics would be taking "a four-week break." That is, back around July 23 I envisioned that KinderComics would take a brief timeout so that I could prep my Fall classes and fix some technical problems, but then come roaring back to life by August 20. My hope, as I said, was "to get KinderComics on a more secure tech footing and then resume blogging on a biweekly basis just in time for the Fall semester." Further, I promised that KinderComics would "delve into teaching in a big way come August 20-27." Out of such promises, embarrassing retractions are made. August 20 would have been one week before the launch of classes at my school (CSU Northridge). As it happens, we are now in Week Seven of classes. Of particular interest to KinderComics is my Honors seminar, English 392, devoted to "Comics, Childhood, and Children's Comics." That course underwent much revision between the time of my last substantial post about it (gulp, May 31) and the launch of class on August 27. For example, four or five of the books I envisioned teaching in 392 have in fact dropped out of the syllabus, since I had to make more room for big issues and assignments (as a course designer, I'm used to that sort of change). As I've noted before, 392 is a bit of a balancing act: the impetus for the class is the current boom in young readers' graphic novels, but the class also seeks to "address the vexed larger history of children’s comics," including, briefly, "the histories of newspaper strips and comic books vis-à-vis children." As I've said, juggling those various topics is a challenge, both practically and intellectually. And now my students and I are right in the middle of that challenge! Working with the reality of 392, as opposed to planning it in the abstract, has required me to adjust my sights and hopes, so as to do the best I can by my students. What was a notional blueprint for a course has become, as it always must, an actual class and a kind of living experiment. I have begun to worry that my approach assumes too much prior knowledge, and to remind myself that any comics course at this level needs to lay a foundation, because students very often come into these courses with no prior experience of Comics Studies, and even little experience as comics readers (I am reminded of Gwen Tarbox's wise comments about gearing her comics-teaching toward her students' needs and concerns). In any case, I have certainly been mindful, these past seven weeks, of the serious challenge we have undertaken as a class. Here is the abridged course description for 392 that I gave out on paper back on Day One (the full syllabus being online, in the form of a class website): And here is the tentative schedule, also given out on Day One (the final schedule being on the class website, and always potentially in flux): Thus far we've kept to the rough contours of this schedule. On the one hand, we need some flexibility in scheduling; OTOH, the students have volunteered for dates to serve as discussion leaders (or "launchers"), so we do have to hold to the schedule as much as we can. Per the schedule, just yesterday we hosted the first of our four scheduled guest speakers: Dr. Lara Saguisag of the College of Staten Island-CUNY. Dr. Saguisag is an experienced children's author, longtime contributor to the Children's Literature Association, and author of the brand-new study, Incorrigibles and Innocents: Constructing Childhood and Citizenship in Progressive Era Comics (Ruters UP), which I consider a watershed book in both comic strip and childhood studies. I am sure that this is going to be an important and generative work for both children's literature and comics scholars. Having read both Dr. Saguisag's article on Buster Brown and some of her work on Peanuts this past week, we joined her via Skype for a freewheeling, spontaneous conversation about childhood studies, children's book publishing in the Philippines, early comic strips, and her research methods and process, as well as her passionate childhood reading (and perhaps more ambivalent adult assessment) of Hergé's Tintin and Lewis Carroll's Alice (with a sprinkling of Roald Dahl for good measure). It was a delight to witness Dr. Saguisag thinking aloud, on her feet as it were, about serious issues, including children's reading, its possible influence, the dark side of humor, and the resonance, or one could even say terrible relevance, of her book's findings for America today, an America once again obsessed with self and Other, inclusion and exclusion, and what it means to be a citizen. Speaking personally, I can't thank Lara enough for her forthrightness, openness, and thoughtfulness, and for her generous, accessible way with everyone in our class. It was a great session. By semester's end, we will have hosted, assuming all goes according to plan, three more speakers, including Skype guests Carol Tilley and Gina Gagliano and in-person visitor Jordan Crane (We Are All Me). To say that I'm looking forward to these sessions would be a huge understatement! What else have we been up to in 392? Well, besides delving into Peanuts and (via Lara Saguisag's work) early American newspaper strips, we've also discussed: the cultural status of comics in the US, in particular the comic book as defined by the scandals of the mid-20th century (this will lead to Dr. Tilley and other sources in a couple of weeks); the children's graphic novel boom (and the current status of graphic novels in public libraries); the introductions to two landmark scholarly books that came out last year, Picturing Childhood: Youth in Transnational Comics (ed. Heimermann and Tullis) and Graphic Novels for Children and Young Adults (ed. Abate and Tarbox); Joe Sutliff Sanders's "chaperoning theory" regarding the difference between comics and picture books, followed by Spiegelman and García Sánchez's Lost in NYC (2015) vis-à-vis De la Peña and Robinson's Last Stop on Market Street (also 2015); and Karasik and Newgarden's How to Read Nancy (2017), alongside, of course, a fair serving of Ernie Bushmiller's Nancy (and Jared Gardner on the history of comic strips). So, it's been a heady brew: history, current events, comics form, constructions of childhood, and more. And we're not even halfway through! Given all this, and three other courses to teach, in addition to writerly, editorial, and service commitments on multiple fronts, I'm forced to admit that maintaining even a biweekly blog is probably going to be beyond me between now and December. On top of that, the technical problems I alluded to back in July have not changed at all (Weebly continues to be anathema to my university), and I may therefore have to make some tough choices, and soon. But KinderComics is not going away; I hope to be back with reviews before Halloween. I continue to read children's and young adult comics (as well as many other sorts of comics) with the usual trancelike fascination, and look forward to sharing my thoughts here -- and, I hope, to hearing from my readers! PS. They are not "children's" texts per se, not in the usual, expected sense anyway, but I'd be remiss if I didn't point my readers to two extraordinary works in comics that I've read this past week, one a memoir of childhood to adulthood, the other a story about childbearing and birthing:  L. Nichols's booklength graphic memoir, Flocks, tells a story of growing up queer, and wracked with guilt, in a fundamentalist community. It's not a screed; it's not an act of revenge. Rather, it's an act of love, through and through, one that transmutes pain into courage and understanding. An achingly personal testimony to the work of transitioning and self-fashioning, it finds its own visual language, its own distinctive vocabulary of braided metaphors, to tell a story of self-in-community, of what it means to find yourself within (and against) your "flocks." Brave, tender, and astonishing. Bless publisher Secret Acres for bringing us the completed version of this long-awaited project.  Just as astonishing, though wholly different, is Lauren Weinstein's graphic memoir of her second childbearing and birthing experience, "Mother's Walk," which makes up the latest issue (No. 17) of Youth in Decline's outstanding quarterly anthology, Frontier. "Mother's Walk" is an explicit and revealing remembrance of childbearing and delivery, with all its rigors, emotional, psychological, and of course physical. I have been anxious to see a graphic memoir like this for some time, one that depicts birth and mothering in raw but loving detail. This is a startling, eloquent, and, as always with Weinstein, unpretentious and gutsy piece of work, one that (she says) anticipates a longer book about childbearing and child-rearing. I can't wait. I recommend these two titles as emphatically as I can recommend any art. PPS. It’s back in print: Joe Lambert’s Annie Sullivan and the Trials of Helen Keller. Ohmigosh, yes.

I continue to wrestle with the design of my my upcoming Fall 2018 course, English 392: Comics, Childhood, and Children’s Comics. My impulse is to focus mainly on the current (i.e. post-2005) boom in children’s and young adult graphic novels in the US, which is what sparked or inspired the class in the first place. Therefore it seems to me that books by Jeff Smith, Raina Telgemeier, and Gene Luen Yang have to be in the mix; exposure to those very successful and influential authors will help lay the groundwork for what's happening today. At the same time, we do need to address the vexed larger history of children’s comics; it seems vital to at least sketch in the histories of newspaper strips and comic books vis-à-vis children (and what of seminal children's comics from, say, Japan, Europe, or Latin America?). So, juggling all this continues to be an intellectual and practical challenge. That said, at this point it seems likely to me that the following books, or selections from them, will be represented in our required reading list: I'm still working out many issues, including the need for greater diversity in genre, format, and cultural content, the scheduling of student presentations and guest speakers, and of course costs. So I would not call this anywhere near the final list. But it's a hint as to where my head is currently at. Frankly, the list is too US-centric for my tastes, but I may have to live with that, given time constraints. I'm not quite sure yet. Work-wise, I'm envisioning student discussion launchers most weeks, a seminar paper (preceded by a formal prospectus), and a weekly or semi-weekly online discussion forum, which is something I can only do when a class is fairly small. I'm also hoping for three to four guest speakers, one a scholar, one a children's publishing pro, and one a comics creator. I hope that one or more of my scholarly colleagues at CSUN can pay a visit as well.  Whew! We'll see. Readers, click on the category "392" if you'd like more behind-the-scenes info on this evolving course...

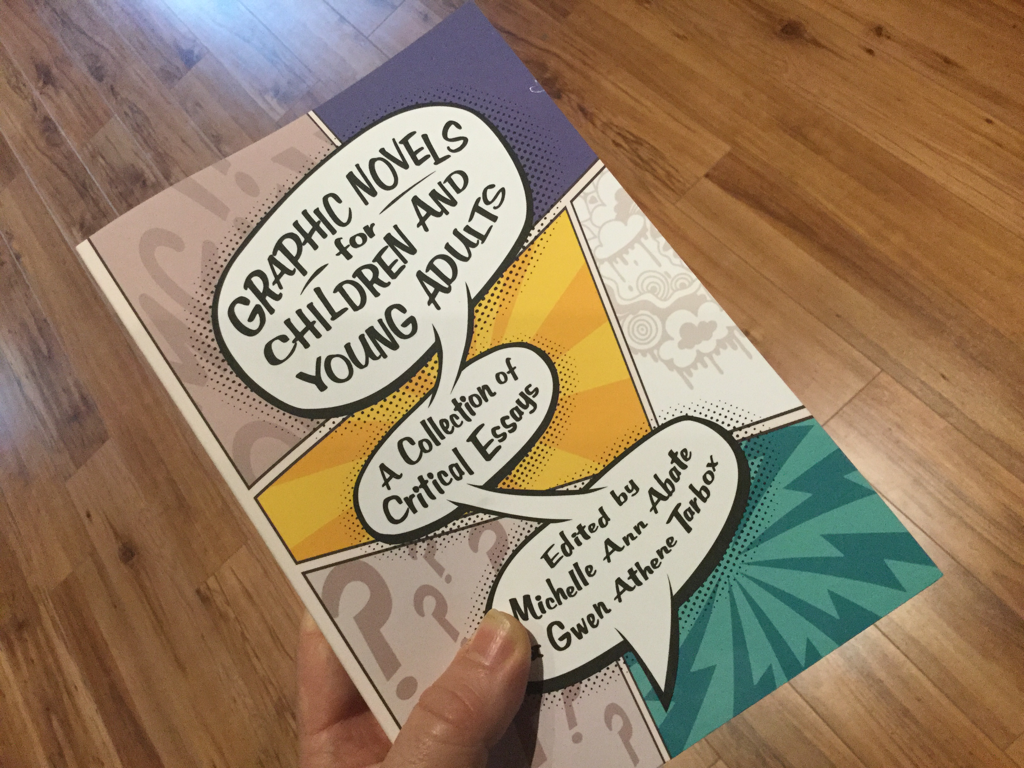

Graphic Novels for Children and Young Adults: A Collection of Critical Essays. Edited by Michelle Ann Abate and Gwen Athene Tarbox. University Press of Mississippi, 2017. ISBN 978-1496818447. Paperback, 372 pages, $30. Newsflash! Graphic Novels for Children and Young Adults (2017), edited by Michelle Ann Abate and Gwen Tarbox, and including a score of essays by diverse authors, has just been (re-) released in paperback. It came out last year, but now, at last, I have a softcover copy of my own that I can annotate and mark up in the usual ruthless way. Yes! This is an essential collection, a landmark in the academic consideration of children's and Young Adult comics. Readers of Gwen's contribution to our Teaching Roundtable may know, or may wish to know, that her post builds on and adds detail to ideas set forth in this book, specifically in her essay, "From Who-villle to Hereville: Integrating Graphic Novels into an Undergraduate Children's Literature Course." Also, Roundtable participant Joe Sutliff Sanders has an essay in the book on children's digital comics! I haven't quite figured out how to teach English 392 yet, but I do know that this is going to be one of the required texts.

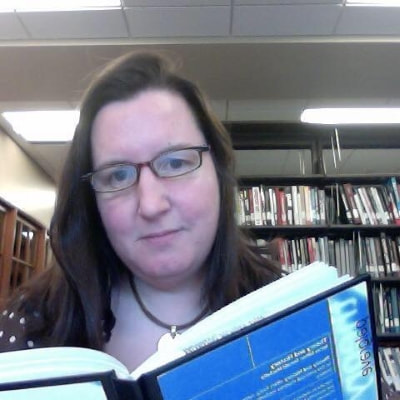

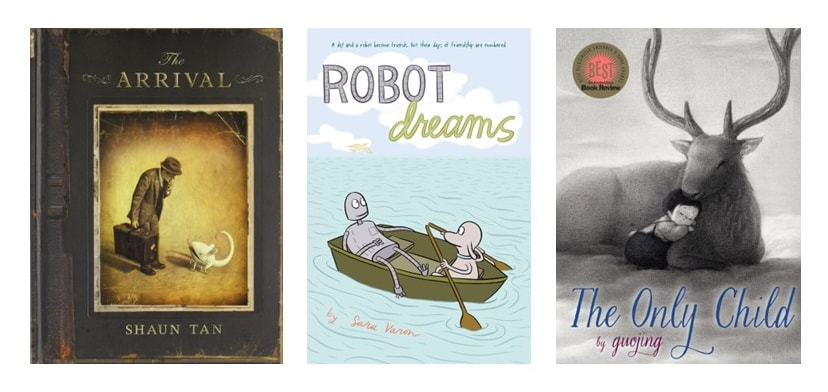

A guest post by Gwen Athene Tarbox The KinderComics Teaching Roundtable continues! Today my colleague Dr. Gwen Athene Tarbox, expert in comics and children's literature and co-editor of the essential Graphic Novels for Children and Young Adults (2017), responds to posts by me and Joe Sutliff Sanders regarding the challenges of teaching comics for and about children. This series arises from my preparations for teaching (this coming Fall) a seminar called Comics, Childhood, and Children’s Comics. Gwen, thank you for contributing your voice here! - Charles Hatfield When it comes to identifying strategies for teaching children’s comics, context matters. As Charles embarks upon the process of developing an elective honors seminar, ENGL 392, Comics, Childhood, and Children’s Comics, he knows that his students have at least some interest in comics and are probably used to researching and writing about interdisciplinary subject matter. The Department of English at California State University, Northridge frequently offers courses in popular culture, and Charles is one of a number of faculty members who integrate comics into their syllabi. Could there possibly be a downside to teaching childhood and children’s comics within a supportive academic environment? Well, not really, but as Charles tells us in his roundtable post, being faced with a seemingly unlimited set of topics and approaches at the nexus of two complex fields makes for a daunting task. Joe, a Lecturer in the Faculty of Education at the University of Cambridge, teaches in a system where students are exposed to a variety of instructors and subjects related to literature, education, and the history of education, as part of a three-year program that combines seminars with tutorials. As he explains in his roundtable post, “I have about two hours to give the students a fiery introduction to the material that will drive them to go educate themselves about the subject once I’m gone.” Many of Joe’s colleagues are interested in visual culture, as are the undergraduate and graduate students with whom he works, but the UK university system relies upon students being much more self-directed, so Joe may end up doing more of his teaching informally, in conferences with individual students. His concerns about teaching canonical texts, which are overwhelmingly male and White, should be shared by anyone who teaches in our fields, and Joe may have to rely upon handing out bibliographies and carving out an online or podcast resource for his students to ensure that they are familiar with a broad spectrum of comics texts. My own experience in the Department of English at Western Michigan University involves integrating comics into ENGL 3820, Literature for the Young Child, and ENGL 3830, Literature for the Intermediate Reader, courses that are required for elementary education majors, but can also serve as general education electives. Creative writing majors, inspired by the success of J.K. Rowling, Jacqueline Woodson, and Kwame Alexander, view 3820 and 3830 as venues for unlocking the secrets of character development or comparing how different media impact the way a narrative unfolds. However, regardless of their motivations for taking my courses, all but a few of my students tell me up front that they are AFRAID of comics—perhaps not as afraid as they are of taking Math 2650, Probability and Statistics for Elementary/Middle School Teachers… but for at least some of my students analyzing comics appears to be as terrifying as being asked to switch on their calculators. My context—preparing future teachers and aspiring authors—compels me to select texts that are frequently used in classrooms or are cutting-edge in terms of their form, and also means that many of my students are encountering comics for the very first time. Typically, I ease my children’s literature undergraduates into the study of comics by spending most of the semester focusing on visual rhetoric, first with picture books and illustrated novels and then moving on to hybrid texts such as Lorena Alvarez’ Nightlights and to films like Paddington or Coco. Then, on the first day of class devoted solely to comics, I hand out a few wordless offerings--Shaun Tan’s The Arrival, Sara Varon’s Robot Dreams, or Guojing’s The Only Child—and ask students to read them aloud. Reading aloud has become a major component of our children’s literature courses, so when students appear flustered and hesitate, it is not because they are unaccustomed to reading in front of their peers. Rather, they are hesitant because, and I give voice here to my students: “How do I know what to read first? What if I interpret something incorrectly? Do I take in the whole page first and summarize it? Or do I talk about each panel? Who is the narrator? Where is the narrator?” All of these questions lead us to a nuts-and-bolts discussion of form and content that occurs organically and is supplemented by excerpts from a variety of critical texts, including Joe’s essay, “Chaperoning Words: Meaning-Making in Comics and Picture Books” (Children’s Literature, 2013), Charles’s “Comic Art, Children's Literature, and the New Comic Studies” (The Lion and the Unicorn, 2006), and Paul Karasik and Mark Newgarden’s newly released How to Read Nancy. Since 2017, I have been working on a book, Children’s and Young Adult Comics, that will come out later this year from Bloomsbury Academic. Like Charles, I have struggled to carve out a narrow enough focus, and like Joe, I feel as if I have only a few short chapters to encourage readers’ investment in children’s comics. Writing an introductory guide to children’s comics has a lot in common with teaching children’s comics insofar as I spend as much time worrying about what I have left out as I do about what is actually on the page. Another venue that has contributed significantly to my understanding of how to share comics with my students is the Comics Alternative Young Readers podcast that I have been a part of since 2015. Working first with Andy Wolverton, and now with Paul Lai, I have had the chance to read dozens of children’s and YA comics every year and to talk about them with experts. Derek Royal, who co-founded and now runs The Comics Alternative, is another great resource whom I consult regularly and with whom I have interviewed a number of children’s comics creators, including Mairghread Scott, Tony Cliff, and Hope Larson. Finally, I was fortunate enough to co-edit Graphic Novels for Children and Young Adults: A Critical Collection (University of Mississippi Press, 2017—now available in paperback), with Michelle Ann Abate, and the process introduced me to over twenty scholars, from traditional literary critics to teacher educators to visual theorists and cultural studies experts, all of whom provide in-depth analyses of a host of contemporary children’s and YA comics. What heartens me the most, then, is that a large community is beginning to congregate around the study and teaching of children’s and YA comics. Charles and Joe, Laura Jiménez, David Low, Nathalie op de Beeck, Carol Tilley, Michelle Ann Abate, Philip Nel, and countless other amazing scholars are helping to create an ongoing dialogue about the intersection of two fields whose fortunes have often been linked, but have rarely been discussed together. And now we have KinderComics, Charles’s blog, as another important resource! (Note: this roundtable will continue in the weeks and months ahead. - CH) Gwen Athene Tarbox is a professor in the Department of English at Western Michigan University, where she teaches courses in children's and YA literature, as well as comics studies. She is the author of The Clubwomen's Daughters: Collectivist Impulses in Progressive-era Girls' Fiction (Routledge, 2001), co-editor with Michelle Ann Abate of Graphic Novels for Children and Young Adults: A Critical Collection (UP of Miss, 2017), and author of an upcoming monograph, Children's and Young Adult Comics, from Bloomsbury Academic. She has written articles on the comics of Hergé and Gene Luen Yang, on teaching comics, and on various topics related to children's literature. She is also co-host, with Paul Lai, of The Comics Alternative's Young Reader podcast, which airs towards the end of every month (www.comicsalternative.com).

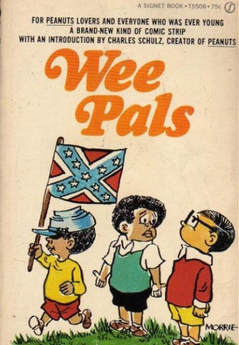

A guest post by Joe Sutliff SandersMy colleague Dr. Joe Sutliff Sanders has kindly agreed to follow up my initial post in a series that I'm calling our Teaching Roundtable. This series stems from my preparations for teaching, in Fall 2018, a course called Comics, Childhood, and Children’s Comics, and my thoughts about the challenges of designing such a course. Thanks, Joe! - Charles Hatfield The best teaching that I have ever done has always been set up just beyond the edge of what I actually understand. You’ll hardly be surprised to learn, then, that I am in love with the idea of this blog. Charles does know a thing or two about comics, but he’s starting this blog conversation about the course not with what he knows, but with where he knows he’s going to have problems. It’s sick; it’s beautiful. I love it. As fate would have it, I happen to be in a very good situation to think about what can go wrong teaching childhood and comics. I’ve just relocated to Cambridge, where the teaching is very, very different from what I’ve done (and experienced) in every other classroom. The number one problem that I keep experiencing is that when the nature of the course wants us to lecture about the center, the books that Have To Be Known, then that nature is insistently nudging us away from the rich work done by people on the margins. For me, this urge toward the center is constant because at Cambridge we teach in a model that might best be understood as serial guest lecturing. Students have a different instructor almost every week, and once I have taught my subject, it might well never come up again for the rest of the term—indeed, the rest of the year. I have about two hours to give the students a fiery introduction to the material that will drive them to go educate themselves about the subject once I’m gone. If I can only ask them to read one book to prepare for my day in front of them, don’t I have to assign them the most canonical, traditional, familiar, central…let’s call it what it is: White…text possible? And Charles isn’t going to find the challenge much easier. Yes, he has the same students for a few months, so with some judicious selection, he can assign both the center and the margin. But there will be times when the nature of the subject seems to insist on safe, familiar choices. For example, while talking about the Comics Code, which was developed by influential White businessmen to protect their interests by playing to 1950s sensibilities of American middle-class propriety, how will he escape a reading list that is White, White, White? The men whose comics sparked the outrage were White; the public intellectual at the center of the debate was White; the men who wrote the Code were White; the books that thrived under the new regime were White. What reading material central to this history will be about anything but Whiteness? Or how about teaching the origins of cartooning? The most common version of the history of comics is populated by White Europeans who had access to the training and venues of publication necessary for a career as a public artist. I’m uncomfortable (to put it mildly) with a module featuring only them, but what are you going to do, not teach the center? These problems arise from comics as a subject matter, but there’s another problem rooted even more deeply in the specific aspect of contexts that Charles has chosen. The title of the course pinpoints "childhood," yes? Childhood’s close association with innocence, which is itself associated with Whiteness (if you don’t believe me, ask Robin Bernstein), is going to make straying from the center even more problematic. Here, as above, the enemy he faces is the nature of the subject. But there is another potential enemy. If—or, knowing Charles, when is the more appropriate word—he edges the reading list and classroom conversation away from innocence, will his students still recognize what they are reading as children’s comics? It’s not just the institution and the subject matter that insist on staying safely in the zone of the canonical…it’s frequently the students as well. So will his students resist when the reading list includes perspectives that don’t fit with the general notion of lily-White childhood? Charles asked me here only to point out his looming problems, but I feel some tiny obligation to offer some possible solutions, too. For example, when teaching the origins of comics, it might do to teach a competing theory, namely the theory that what we call comics today owes a debt to thirteenth-century Japanese art. Frankly, I don’t find that theory convincing (though I think that the influence of another Japanese art form, kamishibai, on contemporary comics has potential), but so what? Our job isn’t to teach proved, finished intellectual ideas, but to help train students to struggle with ideas on their own, and giving them a theory that mostly works will put them in the position of critiquing (or improving) it themselves. Another idea: rather than letting innocence and Whiteness be default categories, rather than letting them force us to defend any deviation from their norms, make them subjects. This is the brilliant move that feminists made with the invention of "masculinity studies": take the thing that has rendered itself invisible and make it the object of study. I’m still concerned that we’ll wind up with all-White reading lists, but this strategy allows us to observe the center without taking the center for granted. Wow, that was fun! Who knew that pointing out other people’s problems and then walking away whistling would be so liberating? Thanks for the invitation, Charles, and I can’t wait to read the posts from the upcoming comics scholars. (Up next: Dr. Gwen Athene Tarbox!) Joe Sutliff Sanders is Lecturer in the Faculty of Education at the University of Cambridge. He is the editor of The Comics of Hergé: When the Lines Are Not So Clear (2016) and the co-editor, with Michelle Ann Abate, of Good Grief! Children and Comics (2016). With Charles, he gave the keynote address on comics and picture books at the annual Children’s Literature Association conference in 2016. His most recent book is A Literature of Questions: Nonfiction for the Critical Child (2018). |

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed