|

Over the past two weeks, the Denver-based nonprofit Pop Culture Classroom has announced the winners of this year's Excellence in Graphic Literature (EGL) Awards. This marks the 7th annual round for the EGL prizes (founded in 2017). First, on June 4, the group announced the winners in eight categories, that is, both fiction and non-fiction winners for Children’s (Pre-K to 4th grade), Middle Grade (5th to 8th grade), Young Adult (9th to 12th grade), and Adult (eighteen years and older) books. At the same time, they announced the finalists for their two big prizes that are not age-leveled, the Book of the Year and the Mosaic Award (which focuses on diversity and inclusivity). Then, on June 10, the group announced the Book of the Year, Shubeik Lubeik by Deena Mohamed, and the Mosaic winner, JAJ: A Haida Manga by Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas: Here is the full list of 2024 EGL winners:

The EGL process does not include public voting, except for a promised "Reader's Choice Award" to be decided by "a public online vote" (I could not find more information about that). In general, the EGLs are decided by professional juries, with the fiction and nonfiction works in each age category judged by a separate jury. Once the category juries have decided upon their finalists and winners, the Book of the Year and Mosaic Award finalists are announced. Those two awards are then judged by the assembled jury chairs in tandem with an EGL Advisory Board (whose current makeup I have not been able to ascertain). Typically, the winners in the several categories also loom large among Book of the Year and Mosaic Award finalists. The EGLs tout their "clearly defined and transparent process," which apparently relies upon rubrics. I gather that all the age categories are ranked according to common criteria and a consistent four-point scale, while the two big awards are judged somewhat differently. The process gives the appearance of orderliness and predictability, though not all categories have been awarded in past years; perhaps the process is still evolving. The yearly juries seem to have a fair degree of turnover. (For more on the judging criteria and process, see here.) Ever since the EGLs were announced, I've been on the fence about them. The awards aim to help teachers and librarians identify those comics that "best advance literacy, learning, and social connection—particularly in educational settings," which to my mind sits awkwardly alongside the nominal emphasis on literature, a term that has usually implied a degree of artistic autonomy if not an ars gratia artis stance. The juries seem to consist solely of librarians and educators (past advisors have included publishing pros, comics retailers, and a very few creators). It's a bit puzzling, though potentially a plus too, that the EGL finalists tend to be so different from those of other comics awards, such as the Eisners. There's nothing wrong with that, or with awards that pay attention to educational value (consider for example the NCTE's Orbis Picture Award for children's nonfiction, or the ALA's Geisel Award for beginning readers). But the "graphic literature" tag seems odd when paired up with what appears to be a language-arts approach whose horizons are primarily academic. Ah well. This tension (or what I perceive as a tension) is not new. Maybe it's at the root of what we call children's literature. It may be that I'm simply too biased toward the notion of artistic autonomy to get comfortable with the EGL criteria. That's on me. In the meantime, reviewing this year's list of EGL finalists has gotten me to check out some new books — which is the whole point, right?

(To get the full benefit of the EGLs, check out the whole list of this year's finalists!)

0 Comments

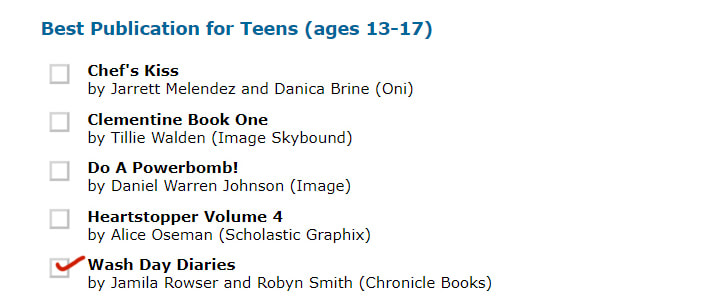

This post is the third in a series of three. On Friday I reviewed this year’s Eisner Award nominees for Kids (roughly, middle-grade readers). Today I turn to the nominees for Teens, that is, Young Adult books (see my post of May 17 for an overview of all young readers’ categories). Once more, I’ve tried to describe every book fairly, while signaling my favorites. The Teens category is amazing this year! Of course, this is all about getting ready to cast my votes before the June 6 deadline! (For info on voting, see here). Blackward, by Lawrence Lindell (Drawn & Quarterly). Four friends run a club for queer, nonbinary, and otherwise “alternative” Black folx. With the help of a bookstore owner, they organize a Black zine fest to build community, while fending off online hate from reactionary, homophobic voices. Blackward is a hilarious, high-spirited mash note to zinesters, organizers, and the kind of friendship that creates new cultural spaces. It’s also a knowing satire of Black community frictions. Lindell’s cartooning is quirky and wild, and sometimes strains to its limits. Yet he uses repetition and braiding to great effect, and the characters are great. I bet this book will change lives. Danger and Other Unknown Risks, by Ryan North and Erica Henderson (Penguin Workshop). Like Mexikid, this made my TCJ Best-of list. Since then, I’ve read many books I wish I had read earlier, so if I were writing that list now, it would look different. This book, though, would still be on it. A brilliantly engineered fantasy about a transformed, postapocalyptic world, Danger offers an adventure in thinking. It rewires a conservative premise (saving the old world) into something wiser (welcoming in the new); ultimately, it’s about embracing change rather than clinging to an idealized past. Ingenious, dizzying, moving, and gobsmackingly drawn by Henderson, this one has captured my heart, and my vote. Frontera, by Julio Anta and Jacoby Salcedo (HarperAlley) In this blend of realism and magic, a young man, Mateo, slips across the Mexico-US border and crosses the Sonoran Desert, aided by the ghost of another man who died during that crossing almost seventy years earlier. The Border Patrol, vigilantes, and dehydration stand between Mateo and his goal, and he nearly dies, though he gets, and gives, help along the way. Frontera’s magical-realist plot works to refute nativism, as Mateo’s quest conveys complex truths about the geography and politics of the border. The climax, however, is generically heroic and feels forced. Graphically sharp, with stylized naturalism and expressive colors. Lights, by Brenna Thummler (Oni Press) The third and final volume in the Sheets series (unknown to me until now). A benign ghost is haunted by his inability to remember his own past, and why he died; his two living friends, eighth-grade ghost-hunters, help him recover those memories, while renegotiating their own complicated friendship. Delicately drawn and colored, Lights is also brilliantly written, filled with subtly observed moments of social negotiation and moral decision-making. Thummler is wise to the ways we typecast other people, limiting who they can be, yet the ending poignantly turns stereotype on its head. Stunningly good (and another one I’d vote for). Monstrous: A Transracial Adoption Story, by Sarah Myer (First Second) In this memoir of intercountry adoption, Sarah, a Korean child of a white family living in rural Maryland, struggles against racism, social ostracism, and bullying – and her fear of her own explosive anger. Frankly, given the unrelenting cruelty shown here, I often felt that her violent outbursts, or moments of fierce self-defense, were justified. Graphically, Monstrous is bold, imaginative, and sometimes frightful; drawing, for Myer, is clearly a high-stakes act of self-invention. Yet the story is anchored by retrospective text that seeks to narrate her experience calmly, from a stance of mature judgment, which softens its impact. Still, powerful work. My Girlfriend’s Child, Vol. 1, by Mamoru Aoi, translation by Hana Allen (Seven Seas) In the first volume of this ongoing manga, a high schooler’s unplanned pregnancy upends her life, tipping her into indecision and emotional turmoil that she cannot share with anyone else, even her sympathetic boyfriend. Aoi’s visuals are sensitive and devastatingly acute. Pensive, almost dreamlike, and marked by long wordless passages, the storytelling balances a sweet, idealized style against unyielding facts. Conversations are muted yet quietly agitated; visual metaphors are understated but fraught. The evocation of anxiety, tenderness, and naivete is overwhelming, and the sense of isolation often harrowing. No preaching here, just minutely observed and heartbreaking drama. I’ll be back. Some final thoughts: I like to treat comics of all varieties, and from all spaces, as cousins, and the comics world as a continuity. I maintain an interest in comics of just about every kind, and I try to follow comics publishing in several sectors. Yet I must admit, it is now impossible for me to “keep up” with comics in the US in any comprehensive way. The Eisner Awards of today, despite their roots in comic book fandom, represent an attempt to spotlight many different kinds of comics, and I appreciate that. Every year I see signs of progress toward greater inclusivity, as well as signs of strain. As a former judge, I can attest that focusing on and weighing so many different kinds of comics is a huge challenge. The Eisners are not guild awards; the US comics field is not a united (much less unionized) industry, and, as my colleague Benjamin Woo has pointed out, there really isn’t any such thing as a single “comics industry.” Nor is there a single comics community – the Eisners represent, and speak to, several different communities. The job of the judges, each year, is to craft a ballot that acknowledges that complexity and seeks out excellence of many different kinds. Honestly, I never read so many comics, in such a brief span, as I did when I served as a judge back in 2013. It was joyous work, but hard. This year’s Eisner ballot includes nominees in thirty-two different categories. I feel qualified to judge in maybe slightly less than half of those categories (what, maybe fourteen? Fifteen?). When I get around to casting my vote (by or before this Thursday, June 6), I will, as usual, struggle to figure out which categories I can fairly cast votes in and which I cannot. I will, as usual, feel as if I’ve missed important things. But I know that thinking about the Eisner nominees always gives me a better sense of what’s happening in the field (fields?). And I know that I greatly enjoy this custom of picking out at least a few categories and trying to get up to speed. My favorites in the Teens category are Lights and Danger and Other Unknown Risks, but I’ve enjoyed the whole process. Congratulations, nominees, and thank you, judges!

This post is the second in a series of three. Yesterday I reviewed this year’s Eisner Award nominees for Early Readers. Today I turn to the nominees for Kids, which I assume means roughly middle-grade readers, around 8 to 12 years old (see my post of May 17 for an overview of all young readers’ categories). Once again, I’ve tried to describe every book fairly, while acknowledging my favorites. I’ll be back soon with a third and final post about the nominees for Teens. This is all about getting ready to cast my votes before the June 6 deadline! (For information about voting, see here). Buzzing, by Samuel Sattin and Rye Hickman (Little, Brown Ink) A book for our time: a neurodivergent Bildungsroman, plus a paean to creative and queer community, in the form of a Dungeons & Dragons-like RPG that gives the protagonist, a young man with OCD, a group of nonjudgmental friends with whom he can be free. He just has to persuade his anxious mother that playing the RPG will be good, not bad, for him. OCD is a familiar topic in disability-themed comics, but Buzzing does something new. Intrusive thoughts are cleverly represented through visual metaphor (a swarm of bees, buzzing), while the cartooning is lively and the cast delightful. Vivid! Mabuhay! by Zachary Sterling (Scholastic Graphix) A Filipino American brother and sister struggle to balance assimilation pressures at school with filial obligations at home. Forced to work on their family’s food truck, they are alienated and resentful – until their family must unite to, I guess, save the world? This acculturation fantasy starts with everyday complaints and embarrassments, then lurches into magic and monsters inspired by Filipino folklore. Sterling’s elastic, manga-flavored cartooning shows his expertise in animation design: characters are distinct, and emote hugely, with broad expressions. The action is frenetic; the plot feels juryrigged. The lessons in filial piety are rather on the nose, I think. Mexikid: A Graphic Memoir, by Pedro Martín (Dial Books for Young Readers). This memoir made my Best-of-2023 list for The Comics Journal. Young Pedro, his many siblings, and mom and dad make an epic road trip to the family’s ancestral hometown in Mexico, there to reunite with his grandfather. Americanized Pedro is often startled by what he learns on the way. Exuberant and graphically tricky, with many inventive, diagram-like pages, Mexikid is a loving tribute to family in all its quirkiness and complexity. In the home stretch, Martín shifts, convincingly, from hilarity to grief, tenderness, and new depths. I’m teaching this in the fall, and it’s my strong favorite in this category. Missing You, by Phellip Willian and Melissa Garabeli. translation by Fabio Ramos (Oni Press) Neotenic cuteness (think Bambi) vies with hard-won lessons about grief and letting go in this gorgeous, disquieting book. A family nurses a wounded fawn back to health, even as they cope with the loss of one of their own. Caring for the deer seems to heal their own hurts, yet they know the deer must someday go back to the woods. Prepare yourself for the inevitable parting (and note, along the way, the deer’s own sad backstory, its own remembered parting). Garabeli’s sumptuous watercolors and elegant pages boost the already considerable power of this of course manipulative, yet beguiling, heartwringer. Saving Sunshine, by Saadia Faruqi and Shazleen Khan (First Second) Feuding twins, sister and brother, make peace during a family trip to Key West. There they learn to care for each other, even as they nurse an enormous loggerhead turtle that lies ailing on the beach. As Muslims from a Pakistani American family, they share a history of struggling against racism and Islamophobia, which informs both their quarreling and their reconciliation. Rendered in digital watercolor, with some lovely, open pages, this book at first leans into adult-centered didacticism (these kids need to learn a lesson), but happily brings nuance and sympathy as it goes. So: predictable arc, but surprising details. Some final thoughts: I'm surprised that Dan Santat's A First Time for Everything was not nominated in this category. It is contending in the category of Best Graphic Memoir, though. (Interestingly, most of the nominated memoirs this year could be considered either middle-grade or YA books.) I obtained all of the above books from the Los Angeles Public Library, save one, Missing You. My sense is that graphic novels published by the children's imprints of the "Big 5 (Hachette, HarperCollins, Macmillan, Penguin Random House, Simon & Schuster) are easy to find in LAPL. Unsurprisingly, so are books from Scholastic, the market leader in children's GN publishing. With other presses, or children's imprints that are not so well known, I had trouble; for example, I could not find a couple of nominated books from Oni Press. We know that the middle-grade graphic novel is (besides manga) the busiest and most profitable sector in US comics publishing. It is also a sector that produces a lot of formulaic work. Reigning themes in middle-grade comics perhaps reflect reigning themes in children's book publishing, period: social negotiation among friends, acculturation, loyalty to family and culture, displacement, loss. Often an adult-centered didacticism clings to books with these themes: I note that the young protagonists of Mabuhay! and Saving Sunshine complain about their parents' decisions, but there is never any suggestion that the parents might need to question their choices (what parents do is not up for debate). When reading middle-grade comics, I often have a feeling that I know just what is happening, and what prosocial messages are meant to be reinforced. I get impatient with that feeling. That said, I've enjoyed reading almost all of this year's middle-grade nominees. To me, the most interesting ones by far are Buzzing and Mexikid, as they are the most formally inventive. It happens that they are also the ones that most clearly resist the thumping didacticism I'm complaining about. Not coincidentally, they have the most complex adult characters as well (though props to Missing You for showing adults and children grieving together). Still to come: this year's Teen nominees!

This post is the first in a series of three. This year's Eisner Award nominations were announced on May 16, and my last post here was a rundown of the nominees in certain categories, especially those focused on young audiences: Early Readers, Kids, and Teens. Since then, I've been requesting books from the Los Angeles Public Library so that I can read all the nominees in those three categories before the June 6 deadline for voting. Award competitions are inevitably biased and troublesome, I know, but as I said last year, I appreciate the heuristic value of this yearly exercise. When the Eisner noms are announced, I start gathering books like crazy! The process keeps me in the swim of things (as a former Eisner judge, I like to stay involved). I note that last year LAPL was able to supply me with most of the nominees, and the same has been true this year; young readers' graphic books appear to be well represented in my public library. This post, the first of three, focuses on the Early Readers nominations, which I have finished reading as of today. I've tried to describe each nominee fairly, while spotlighting my favorites. Posts on the Kids and Teens categories will follow soon. Bigfoot and Nessie: The Art of Getting Noticed, by Chelsea M. Campbell and Laura Knetzger (Penguin Workshop) Two cryptids – Bigfoot, who cannot get noticed by the world, and Nessie, who would rather not be – form a mutually affirming friendship. Together, they make art when no one is looking, bonding over spontaneous creative risk-taking. Yet their friendship is tested when Bigfoot achieves the fame he hungers for. This is one of those cartooned books that looks simple on the surface but is restlessly designed and dense. Knetzger’s bright, candy-colored pages are elaborate and multilayered, sometimes perhaps to the point of confusion; a spread of the two friends drawing chalk art is a wonder. A fragile conceit, lovingly rendered. Burt the Beetle Lives Here! by Ashley Spires (Kids Can Press) Burt, a June beetle, thinks it might be best to get out from under his leaf and find a more permanent home. It turns out that what works for carpenter ants, tent caterpillars, wasps, or cathedral termites doesn’t work for him. As Burt bounces from one slapstick moment to another, trying out different things, the bland, omniscient narration keeps informing him (and us) about what he and other critters need. Crisp digital cartooning and subtly varied layouts (most pages have fewer than four panels) serve both the humor and the science lesson. Format-wise, this reminds me of a TOON book. Go-Go Guys, by Rowboat Watkins (Chronicle Books) Thumping iambs and breathless running text lend a lockstep rhythm, but also surprises, to a rollicking picture book about revved-up “guys” who cannot go to sleep (but end up going to the moon). The art is at once wild and decorous: full of energy, yet within safe, neat bounds. Watkins’ drawings (seemingly pencil and watercolor, but perhaps also digital?) have the delicacy of Arnold Lobel, but then again, his screwball humor recalls James Marshall. The book is perhaps not as anarchic as it wants to be, but I dig the sudden lunges and dynamic layouts. A great read-aloud, I bet. The Light Inside, by Dan Misdea (Penguin Workshop) This pint-sized book (5.75 x 5.75 inches, 32 pages) tells a gentle, wordless story about a child with a jack-o’-lantern head who travels through a spooky landscape to recover his stuffed animal, taken by a black cat. Creepy things turn out to be benign, and adversaries turn out to be helpers. The story has an almost beatific calm despite the Gothic trappings. Misdea, a New Yorker cartoonist, prioritizes design and simplicity (his uncle, Patrick McDonnell of Mutts fame, has been an inspiration). The book’s small pages somehow make room for between three and seven panels each, with perfect clarity. Charming. Milk and Mocha: Our Little Happiness, by Melani Sie (Andrews McMeel) Collected strips about two bears and their pet dino, from the heavily merchandised social media phenom MilkMochaBear. These characters began as stickers for the LINE app – emoji, basically – and have since spread. The comics strike me as ideal for Instagram: short, spare, and cute, in the kawaii sense, with a whiff of Sanrio. But are they for early readers? They read as humorous valentines for adult couples: bite-sized comic affirmations of love and domesticity. Often, they involve social media (the bears are continually on their phones). The humor depends on routine and slight nuances. I confess, this nomination puzzles me. Tacos Today: El Toro & Friends, by Raúl the Third, colors by Elaine Bay (Versify) My emphatic pick in this category, this vibrant, positively Kirbyesque explosion of energy boasts super-cool characters and restive page design. A diverse cast of anthropomorphic critter-kids from “Ricky Ratón’s School of Lucha” gets mucha hambre and goes out for tacos, though they don’t have the dinero to pay. A demonstration of their lucha skills saves the day. Raúl the Third draws up a storm here, with a punky, inky roughness that translates beautifully into digitally finished pages (OMG, Bay’s colors!). Mingled Spanish and English text, and myriad background cues, make this a multicultural bonanza inviting read-aloud interaction and conversation. Fantastic. Some final thoughts: This category feels more adventurous this year than it did last year. My emphatic faves are The Light Inside and especially Tacos Today, but most of the books are interesting, and several of them are visually daring. I continue to be interested in the way this category makes room for picture books, which is an important, underacknowledged format for children’s comics. That's encouraging. BTW, I did not know any of these books before the Eisner nominations were announced. I found all of them save one (Milk and Mocha) through LAPL.

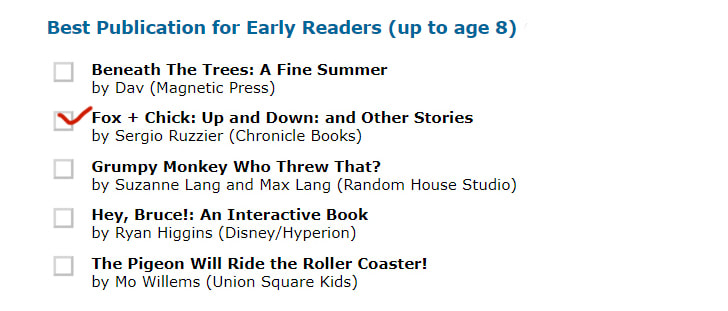

The nominations for this year's Will Eisner Comic Industry Awards (celebrating work published in 2023) were just announced yesterday. Of course I'm already looking up and bookmarking things I want to read, with a big thank you to judges Ryan Claytor, Chris Couch, Andréa Gilroy, Joseph Illidge, Mathias Lewis, and Jillian Rudes! I always learn from, and of course debate, the Eisner nominations. Unsurprisingly, there are always some choices that leave me bewildered and omissions that make me sad. But I know what this job is like from the inside out (having served as an Eisner judge in 2013). It's not easy. Yes, it's delightful work, but it's heavy, and it's not casual. It takes a lot of negotiation. Props to the judges for making the tough calls and shining spotlights on so many deserving works. Below are the nominees in the three categories of special interest to KinderComics, that is, those focused on young readers: Early Readers, Kids, and Teens. I've also noted two other categories of special interest to me that I think are particularly strong this year, Best Graphic Memoir and Best Academic/Scholarly Work. Where possible, I've linked the title of each work to a publisher's webpage, FYI. In the weeks ahead, and especially prior to the June 6 voting deadline, I hope to read and comment on many of the nominees in Early Readers, Kids, and Teens categories. Thus far, I've read only a few. I have requests out at my local branch of LAPL for as many of these books as I can get! I've found that bingeing on the Eisner noms each year is a great learning experience! Best Publication for Early Readers I'm ashamed to say that I haven't read any of these yet!

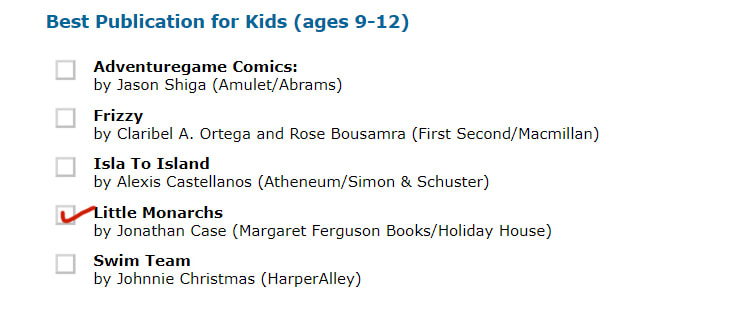

Best Publication for Kids

Best Publication for Teens

Best Graphic Memoir This is the category I'm most prepared for this year, having read four out of the six noms so far. I'm interested to see that several of these could also be nominated in young readers' categories.

Best Academic/Scholarly Work A fantastic group this year! Innovative and important work all round.

I won't begin to make predictions about which books and creators will win. Suffice to say that my reading for the next few weeks will be interesting! PS. Among the Eisner noms I've read lately that didn't make my Best of 2023 list, but I wish had, are Mexikid; A First Time for Everything; Bill Griffith's Three Rocks: The Story of Ernie Bushmiller; K. Wroten's Eden II; Tillie Walden's Clementine, Book Two; and Kelly Sue DeConnick et al.'s Wonder Woman Historia: The Amazons.

PPS. Among things I dearly wish had made the Eisner ballot? Noah Van Sciver's Maple Terrace; Wes Craig's Kaya; Ryan Holmberg's translation of Tsuge's Nejishiki; Ryan North et al.'s Fantastic Four; Craig Thompson's Ginseng Roots; Tom King and Elsa Charretier's continuing Love Everlasting; Tom Kaczynski's Cartoon Dialectics #4; Joe Kessler's The Gull Yettin; Seth's Palookaville #24; Chantal Montellier's Social Fiction; and Daniel Clowes's Monica. Insert a big Schulzian SIGH here for all of these. <3 I like to keep up with the Eisner Awards. I'm a former judge, I value recognitions of excellence in the comics world (even when they're contentious), and I like staying in touch with the process. Honestly, it can be hard to find and read every single nominee, but each year I pay particular attention to, and try to spend time with, all the nominees in the young readers' categories. Currently, that means three categories: Early Readers, Kids (ages 9-12), and Teens. Over the past week, I've read about ten books to get up to speed! I'm told that today, June 9, is the last day to cast votes (officially, the vote is "open until June 10, 2023 12:01 AM (GMT-05:00) Eastern Time"). So, this evening I'm going to vote in as many categories as I feel qualified to vote in! This year's Eisner process has been especially vexed and controversial (leading to a retroactive withdrawal from the ballot). The ballot has been a bit mystifying to me, with some, IMO, startling omissions and puzzling categorizations. But controversy is in the nature of the awards, and I still appreciate the heuristic value of this, let's say, yearly exercise. Here are my thoughts on the Early Reader, Kids, and Teens categories:  Early Readers: I admit, this is not a category that interests me much this year. There are some lovely images here (for sheer sumptuousness, Dav's Disneyesque watercolors are hard to beat), and some nice comic bits (the page-turns of Higgins, the pacing of Willems), but for the most part these books strike me as pat and aesthetically undaring. There's a lot of shtick here, which tires me out. I miss seeing some good TOON Books in this category; 2022 seems to have been fallow for them. That said, my choice here is this charming, quietly ironic, aesthetically delicate take on friendship and learning:  Kids (9-12): This is a more interesting category by far, in fact one of the deepest in this year's ballot. The craft on display is impressive (dig the cartooning in Frizzy and Swim Team), and the ambition (dig the near-wordless storytelling of Isla to Island, a complex tale of immigration, loss, and discovery; or the interactive, formally ingenious Adventuregame). But my hands-down choice is Little Monarchs, an extraordinary piece of worldmaking, which is cartooned with an Alex Toth-like economy that reminds me of elegant classicists like Jaime Hernandez, R. Kikuo Johnson, and Chris Samnee. An amazing book, so dense, involving, subtle, and beautiful: Teens: It's nice to see Tillie Walden in this category, for a book that is a change of pace for her. But I think the outstanding title here is the already much-talked about, groundbreaking Wash Day Diaries, a suite of stories about four Black women and the strength of their friendship and interconnection. Every character in this book has a backstory, but Rowser and Smith smartly leave us guessing, focusing on the energy, grace, and good humor of the four. Darkness marks the edges of the story, but joy wins out. The book seems casual, the way eavesdropping on good friends can, but that's deceptive; there's a lot going on. The chapter devoted to their "group chat" is a wonder of form as well as characterization. I admit that I didn't see this as a YA book at first, but then, I usually have that reaction to books that turn out to be very good YA books! A few observations:

The 2021 Eisner Awards were announced in a virtual ceremony or video released on Friday, July 23, part of Comic-Con@Home. The ceremony, hosted (once again) by actor Phil LaMarr, runs just over an hour and can be viewed via YouTube on the Comic-Con International channel: https://youtu.be/RuVslpoC2nI This year's was a solid and fairly satisfying Eisner Awards crop, and mostly unsurprising, given the ballot announced on June 9. Out of the thirty-two award categories, I was mildly surprised by five or six. Going into the ceremony, I had strong feelings about just three or four categories. In almost all cases, my daughter Nami was able to call the winner just before LaMarr announced it! These past few weeks, I’ve been checking out a number of Eisner nominees and winners from my local library, the LAPL. Good reading! I congratulate all of this year's winners, and, again, particularly congratulate the nominees in the Academic/Scholarly Work category. Readers, do seek out all the books in that category, especially the Award-winner, Rebecca Wanzo's The Content of Our Caricature, which is innovative and important! As I've said before, when that book came to my mailbox, I stood transfixed and read a whole chapter before even sitting down. The book is brave, startling, and bracing: a must. My congratulations to Dr. Wanzo on this well deserved (further) recognition! PS. I hope I will be able to write up some of my recent reading here at KinderComics. This is a time of bereavement and struggle for my family, so my writing and reading time is sorely limited, but I do hope to reconnect, here, in this space I've tended for so long. Peace, everybody.

The nominees for the 2021 Will Eisner Comics Industry Awards – the most prestigious set of awards given within the US comic book and graphic novel industries – were announced on June 9. This year’s judging panel consisted of comics retailer Marco Davanzo, Comic-Con International board member Shelley Fruchey, librarian Pamela Jackson (San Diego State University), creator/publisher Keithan Jones, educator Alonso Nuñez, and comics historian Jim Thompson. As usual, the ballot recognizes an eclectic mix of material, with awards in thirty-two categories, including the following three young-reader categories: Best Publication for Early Readers (up to age 8)

Wow, what a list! This year’s ballot looks smart and interesting to me. As always, I could gripe about oversights, omissions, and puzzling choices. Of course! I’ve been an Eisner judge myself (2013), so I know that the job is challenging, even overwhelming. I get it. The Eisners represent several different communities (after all, they are not a guild prize like the Oscars or the Grammys) and it’s not easy for the yearly ballot to satisfy everyone. That said, I am learning a lot by looking up this year’s nominees. In addition to the nominees in the dedicated young-reader categories above, there are nominations in many other categories that may interest followers of children’s and young adult comics. What follows is not an exhaustive list, but just a few items that I noticed: Best Single Issue:

Readers, I urge you to seek out all of these works!  On a personal note, I'm honored that the book I co-edited with Bart Beaty, Comics Studies: A Guidebook (Rutgers University Press), has been nominated for an Eisner in the category Best Academic/Scholarly Work. This is a testimony to the superb work of our co-contributors: Jan Baetens, Isaac Cates, Mel Gibson, Ian Gordon, Martha Kuhlman, Frenchy Lunning, Brian MacAuley, Matt McAllister, Andrei Molotiu, Philip Nel, Roger Sabin, Kalervo Sinervo, Marc Singer, Theresa Tensuan, Shannon Tien, Darren Wershler, Gillian Whitlock, and Benjamin Woo. Our Guidebook is in excellent company. The other nominees for Best Academic/Scholarly Work are:

More than one of these books has fundamentally changed the way I look at my field. Again, readers, I urge you to check out these thought-provoking works. Also, check out the work in the other comics scholarship category, that of Best Comics-Related Book:

Update, June 29, 2020: Due to a technical or information-security problem, the Eisner Award voting has been restarted from scratch on a new online platform, and the new deadline for votes extended until tomorrow, Tuesday, June 30, at 11:59pm Pacific. Reportedly, voters who previously cast a ballot have been sent emails inviting them to vote again. I'm voting again at this very moment! Voting for this year’s Will Eisner Comic Industry Awards (the Eisners for short) will soon end, so file this post under "belated." Sigh. Unfortunately, the current COVID-19 lockdown and related stresses have slowed me down, so this comes late.  But: onward. This year’s list of Eisner nominees (announced on June 4) is another extraordinary snapshot of a (as ever) divided field that encompasses multiple, sometimes divergent, communities, a field that often feels like many fields at once. Having been an Eisner judge (2013), I can attest to what a joy and challenge it is to access, read, and debate so many different kinds of comics with other judges assembled from several different disciplines. If the final results of the Eisner voting are often an index of popularity, or simply of the kinds of comics that get noticed readily in shops, the ballot is less predictable and more expansive, reflecting the painstaking efforts of longtime Eisner Award Administrator Jackie Estrada and the diverse, carefully-selected judging panels she recruits. Those panels are typically balanced to include comics creators, retailers, journalists, critics, and scholars, and, once recruited, are fully autonomous and, in my experience, absolutely honest about what they like and don’t. It’s a great, once-in-a-lifetime gig. In my case, I spent a long weekend in a San Diego hotel conferring with my fellow judges. This year’s panel, however, has had to judge remotely, connecting via social media and Zoom (I can’t imagine). The process reportedly took two months longer than usual. But the panel sounds like it was an amazing group: journalist and scholar Jamie Coville; graphic novel reviewer Martha Cornog; my friend, scholar/teacher/designer Michael Dooley; comics writer and novelist Alex Grecian; podcaster and Comic-Con volunteer Simon Jimenez; and retailer and festival organizer Laura O’Meara. Michael has some telling comments and reflections on this year’s process, and his own values and priorities as a judge, in a PRINT magazine interviewer with Steven Heller that came out last week (worth a look). I agree with Michael that the list of nominees is the important thing, “the news that readers can most usefully use”; like him, I didn’t particularly care about who won the final voting, but loved taking part in the crafting of the ballot. This year’s list is an excellent and illuminating guide to this particular moment in comics. As I said, the comics community often feels like several disparate communities: different, even conflicting, publics and aesthetic formations. The Eisners, unlike guild awards such as the Oscars or Tonys, are voted on by a wide, dispersed group not held together by membership in a professional body, and the judging and voting processes reflect that. Jackie Estrada has deliberately set out to recruit diverse judges that can represent some of the many publics that make up the comics field and yet can also dialogue across boundaries and bring some focus to the awards. The continuing excellence of the yearly ballots bears out the wisdom of her efforts – congratulations, once again, to the judges and Jackie for a job well done! Of particular interest to KinderComics are the nominees in the young readers’ categories, and this year they’re terrific: Best Publication for Early Readers

Best Publication for Kids

(I confess to some disappointment here. Where is Luke Pearson's Hilda and the Mountain King? Where's Jen Wang's superb Stargazing?) Best Publication for Teens

I also want to note that Lois Lowry’s classic dystopia for young readers, The Giver, has been adapted by P. Craig Russell into a graphic novel nominated in the category Best Adaptation from Another Medium. In addition, children’s and YA comics creators were nominated in several other categories:

A few more observations: All told, there are some 180 Eisner nominees this year, spread over thirty-one categories (again, the full list is here). This year’s judges have moved even farther afield that usual, testifying to the increasing impact of not only children’s and YA comics but also digital comics, native webcomics, and other sectors beyond the traditional comic book shop. The ballot strays off the usual beaten paths and is an education in itself. While there are a number of categories in which I do not have a strong opinion (teaching through the pandemic has curtailed my comics reading these past few months), I’m greatly impressed by the lists for Best Short Story, Best Webcomic, Best Archival Collection/Project—Strips, Best Graphic Album—New, and the three journalistic and scholarly categories: Best Comics-Related Periodical/Journalism, Best Comics-Related Book, and Best Academic/Scholarly Work. In fact, I just have to list the nominees in the following three categories, which are incredible: Best Academic/Scholarly Work(This is a great year for comics studies titles. Dig the diversity of topics and publishers!)

Best Webcomic(As soon as the ballot came out, I went and read or re-read all the nominees, Wow!)

Best Short Story(Again, a rich, revelatory list!)

Finally, I commend the judges for inducting artists Nell Brinkley and E. Simms Campbell into the Eisner Hall of Fame, and for nominating fourteen others, out of which four will be inducted by the voters: Alison Bechdel, Howard Cruse, Moto Hagio, Don Heck, Jeffrey Catherine Jones, Francoise Mouly, Keiji Nakazawa, Thomas Nast, Lily Renée Peter Phillips, Stan Sakai, Louise Simonson, Don and Maggie Thompson, James Warren, and Bill Watterson. (That’s a hard list to choose from!) A final note: The Eisner winners were to be have been announced at the usual gala ceremony on Friday night (July 24) during the San Diego Comic-Con; now, however, they will be announced online instead, sometime in July I hear, most likely as part of Comic-Con@Home. Details TBA.

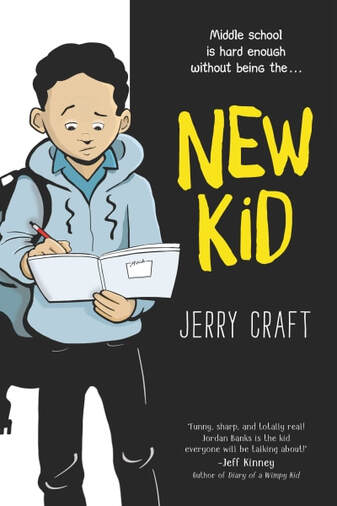

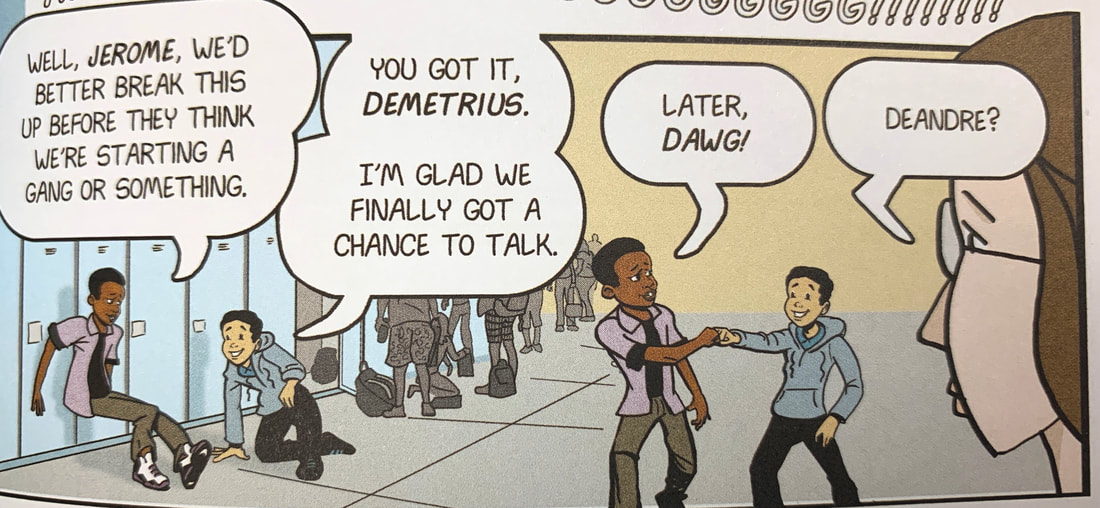

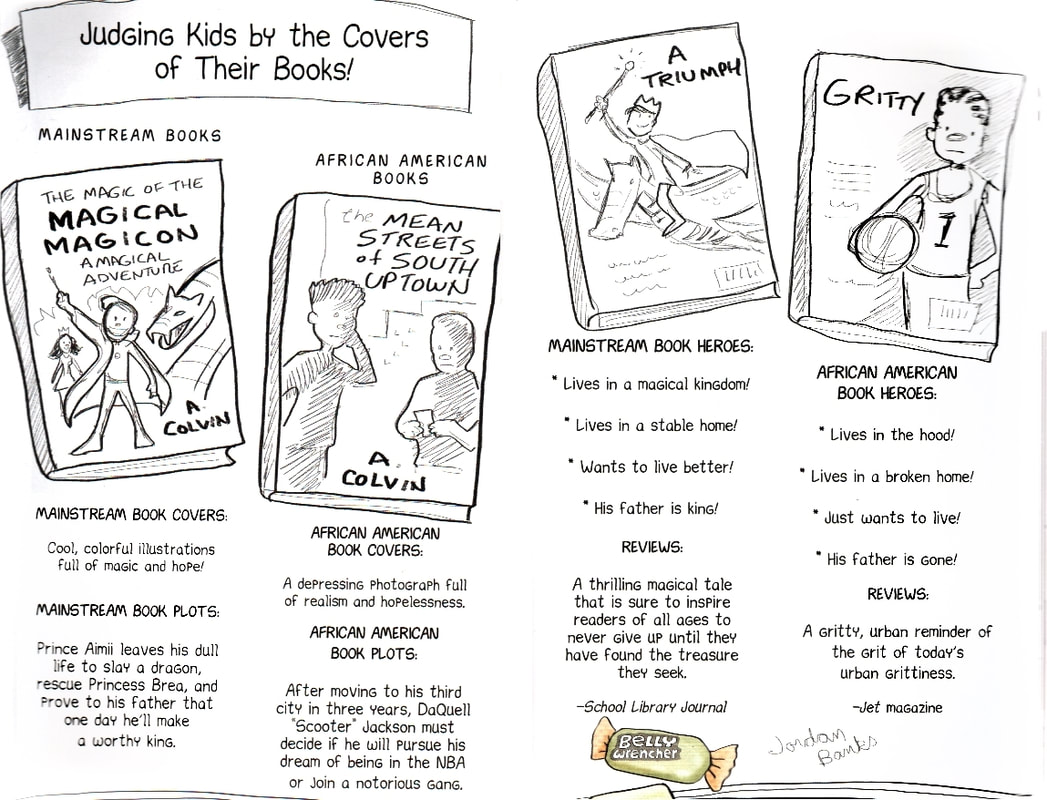

New Kid. By Jerry Craft. Color by Jim Callahan. Harper. ISBN 978-0062691194 (softcover), $12.99; ISBN 978-0062691200 (hardcover), $21.99. 256 pages. A month ago, Jerry Craft’s graphic novel New Kid became the first comic to win the coveted Newbery Medal for children’s literature. I came to New Kid late, and KinderComics readers may remember that I did not include it among my faves of 2019. I wish I had. I confess I put off reading New Kid because I did not love its graphic style, which struck me as cobbled together digitally, with elements seemingly cloned, rescaled, and reused across its pages. At first the work looked patchy to me, compositionally choppy, and too tech-dependent for my tastes. I didn’t see the visual flow or elegance of design that I tend to crave. So, I was closed-mind about this one, I have to say. (This would not be the first time my aesthetic preferences blocked me from recognizing good work. For instance, I recently read Maggie Thrash’s fine comics memoir Honor Girl, done in a seemingly naive watercolor style, and realized that I had been avoiding that one also. I had sold it short.) New Kid deserves better from me. It’s an excellent school story, not only smartly written but visually clever and insinuating throughout. Craft, with exceeding sharpness, depicts African American scholarship boy Jordan Banks and his private school mates at awkward intersections of race, class, and gender. Indeed New Kid, with miraculously high spirits, examines the effects of racism and classism without ever actually breathing those words. Craft is astute and at times can be blunt, but is also endlessly subtle; his touch is marvelously light, yet telling. New Kid manages to be hopeful and often funny, even while acknowledging racism as both systemic feature and stubborn habit. The story of one school year, New Kid gently critiques the class aspirations of private school parents, the casual racist carelessness of teachers, and the blunders of overcompensatory liberal tone-deafness, all while painting Jordan and his fellow students as canny survivors. The book abounds with sly, knowing recognitions, unexplained but pointed, including many gags that show Jordan trying to deal quietly with racial and class-based awkwardness. A middle-class Black boy in a (to him) new school that defines the very notion of privilege, Jordan is alive to the implications of every social move. Craft’s approach is at once realistic, worldly, amused, jaded even, and yet guardedly optimistic; he is properly impatient with ingrained prejudice, yet fatalistically aware that, well, young people have to get on in this broken world. New Kid humorously acknowledges the ways young people of color are too often seen, or rather mis-recognized, and fences smartly with the usual stereotypes about young urban Blackness. The school kids mostly come out well here: they see and deal with social inequality and the willed blindness of adults while upholding their sense of humor and camaraderie. Running gags and droll in-jokes are everywhere: a kind of code and coping mechanism among the kids. For example, Jordan and his classmate Drew call each other mistaken names throughout, mimicking the cluelessness of their white teacher who cannot distinguish one Black student from another. The jokes in New Kid are not just funny, but insightful—as are the young people who tell them. One of the best things in New Kid is a self-reflexive spoof of children’s and young adult publishing that mocks the narrowness of Black depictions in the field. This spread made me laugh out loud (please forgive my crummy scan): If, as Philip Nel argues in Was the Cat in the Hat Black?, the cordoning off of genres marks a de facto line of segregation (Genre Is the New Jim Crow, in Nel’s phrasing), then Craft gets this exactly, and takes the whole publishing field to task. Indeed, the sight of a “gritty” novel for Black teen readers becomes a repeated joke in New Kid, one that stings with its insight but is also downright hilarious. Bravo! This is a supremely wise and charming book that jousts with, and defeats, a thousand cliches.

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed