|

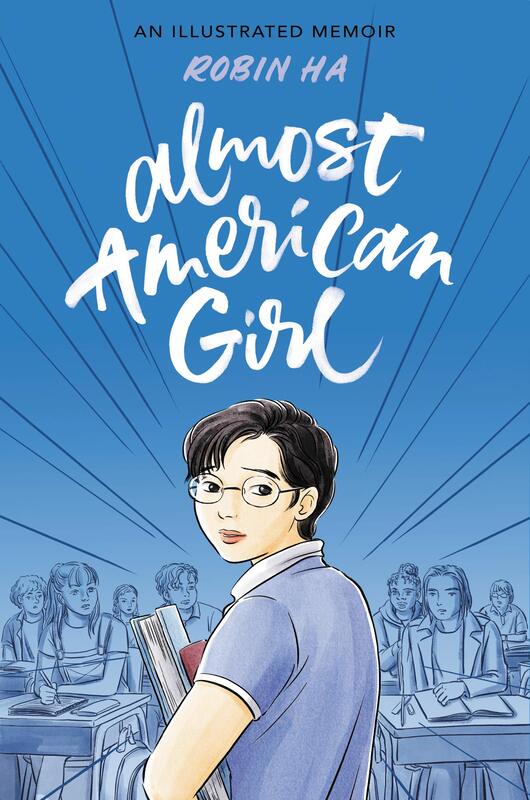

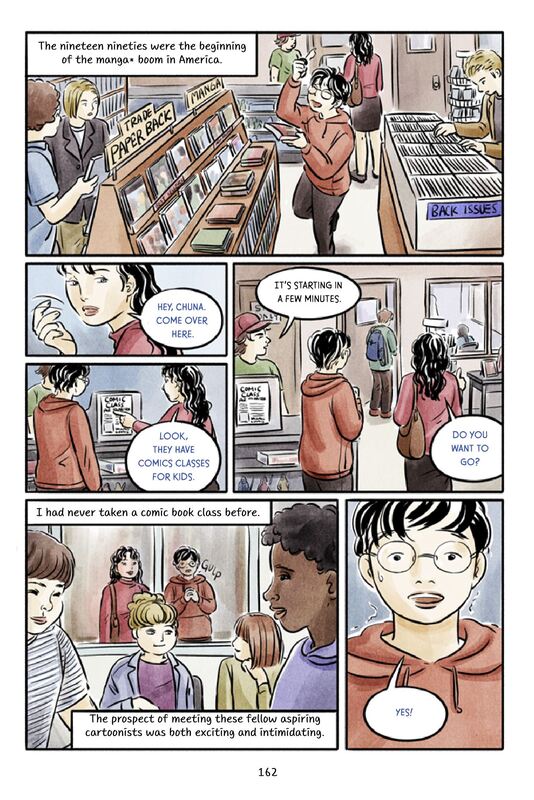

Almost American Girl. By Robin Ha. Balzer + Bray / HarperAlley. Paperback: ISBN 978-0062685094, US$12.99. Also in hardcover, Kindle, comiXology, and Nook. 240 pages. Robin Ha’s Almost American Girl, a Korean American memoir of emigration and acculturation, evokes hard truths and traumatic memories through a mostly gentle, almost decorous style. The style belies Ha’s toughness. A complex story of cultural displacement and loss, but then again gradual near-assimilation—or, better, ongoing negotiation of identity—Almost American Girl boasts a delicate watercolor aesthetic and, by contrast, stilted digital lettering. The style is sometimes straitened or stiff, yet tender and personal; the balance suggests both tentativeness and poise. I confess, I didn’t warm to it easily—but Ha’s story has stayed with me, provocatively. Young Robin, raised in Seoul, suddenly finds herself uprooted and forced to adapt to life in the US. Her mother, a single parent, makes that choice, indeed all the choices, for them. Ha’s complex relationship to her mother—who at first, it seems, did not want this book to get made—accounts for Almost American Girl’s pointed, unsentimental, and clear-eyed qualities. The book relives Ha’s memories of anger toward her mother, which could not have been easy to set down on the page, but also portrays her mom as a self-driven woman determined to break out of a South Korean society premised on gender conformity and suffocating moralism. Gradually, Robin develops empathy for her mother’s struggles, even as she learns to be critical of stereotypic gendering in her own life—and it is her (re)discovery of comics as an artistic outlet, a move encouraged by her mom, that enables Robin to stake out these positions. So, to say that Ha’s treatment of her mother is necessarily double-edged would be an understatement. The negotiations behind the book’s making must have been complicated. Just so, the finished book is hard and sort of unfinished. Much of it replays old hurts with fresh anger. In the home stretch, though, Ha fast-forwards into life changes that bring a warmer, more resolved ending; the book seems to leapfrog to its finish. This shift perhaps comes a bit too fast, reflecting, I suppose, the YA genre’s demand for at least some provisional resolution. However, to Ha’s credit, hanging questions remain. The result is clear but not pat, and emotionally rich. Almost American Girl joins other graphic memoirs of divided identity and enculturation in the US: comics about immigrants and immigrants’ children working their way into a robust but ambivalent sense of Americanness (Thi Bui, say, or Malaka Gharib). In this post-Raina moment of comics memoirs for young readers, the graphic story of renegotiated identity has become a distinct and powerful vein of storytelling. Ha adds worthily to that growing list, with work that is at once aesthetically subdued yet piercingly written. It’s very good, and I imagine it will make a big difference for many readers. PS. Dig Ha and Raina Telgemeier’s online panel from the recent Comic-Con at Home: a warm, collegial chat (with some drawing!). This has been one of my favorites of the many online “convention” events I’ve watched recently; you can tell that these authors are used to fielding questions from readers young and old. It is hard for me to imagine a Comic-Con panel like this fifteen years ago. Thank goodness the world keeps changing! Here's the video: Also, Robin Ha has a nice how-to / process video on YouTube, from this past May, courtesy of Epic Reads: see here.

0 Comments

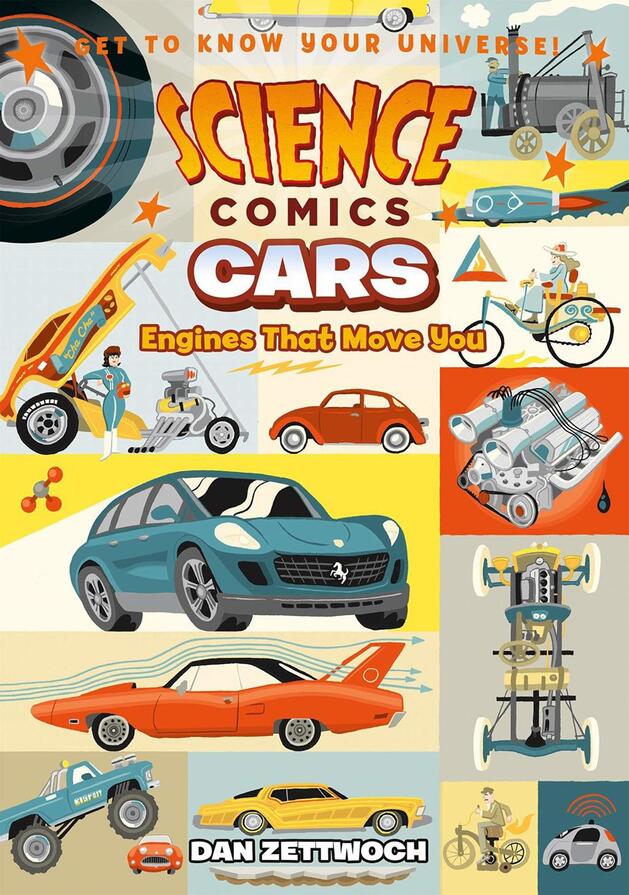

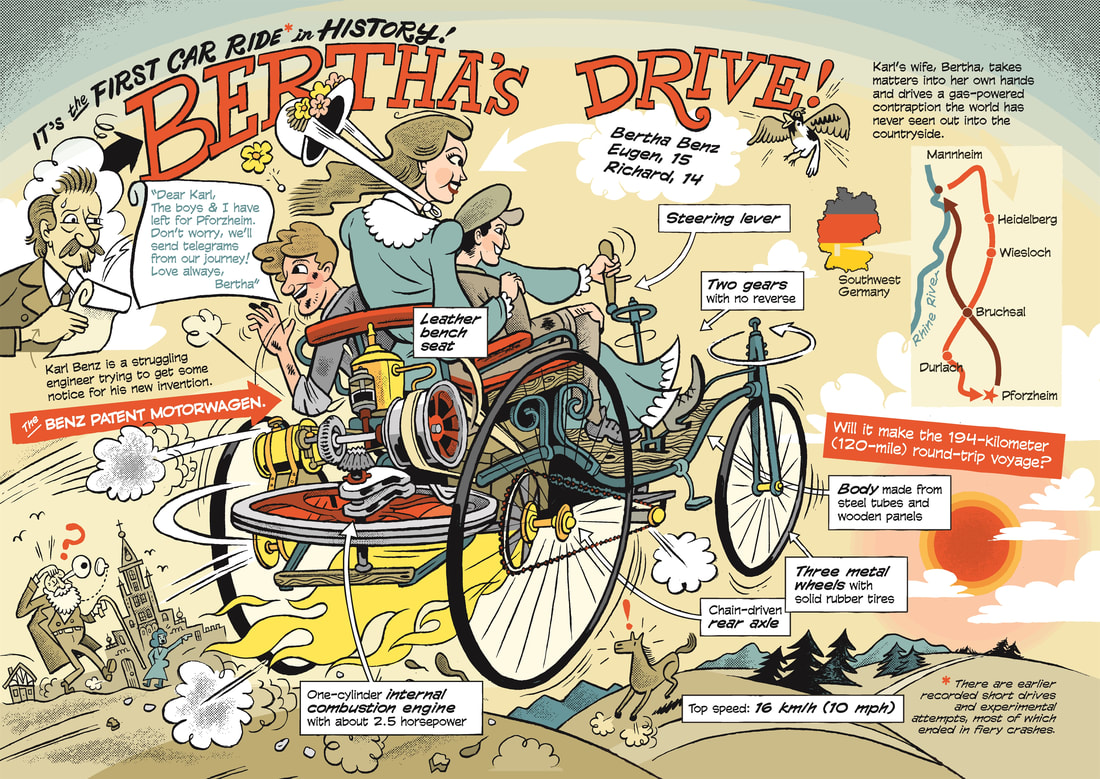

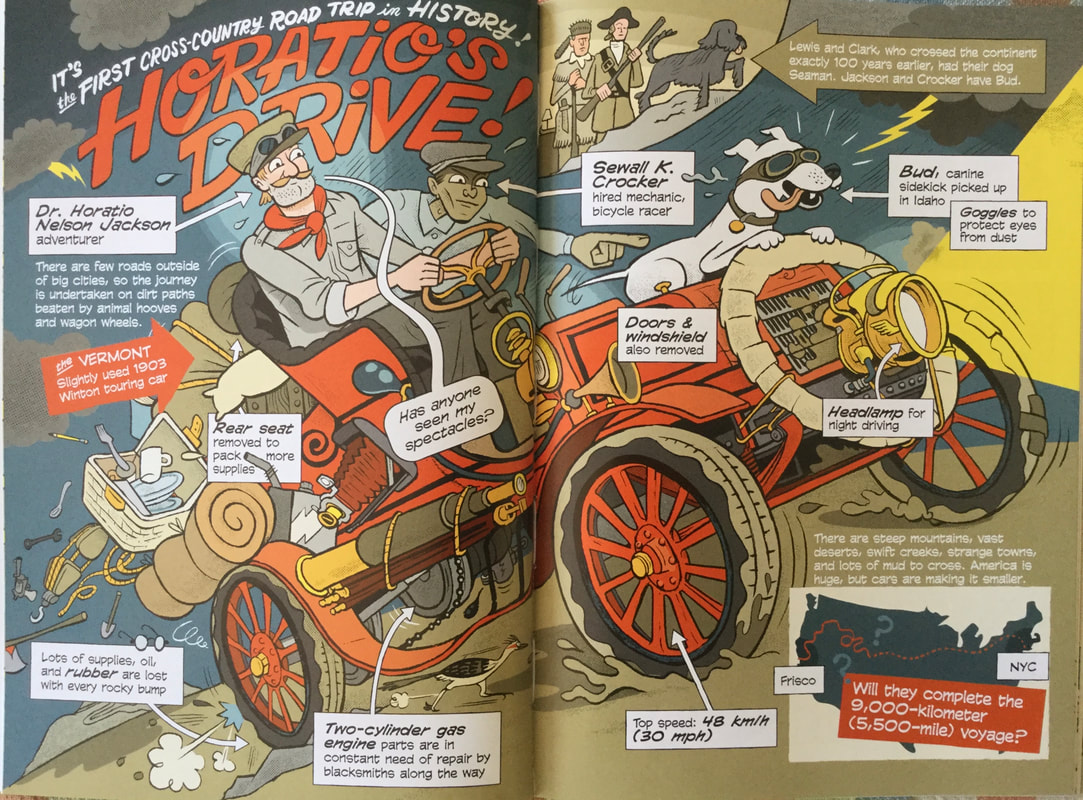

Science Comics: Cars: Engines That Move You. By Dan Zettwoch. Edited by Dave Roman; designed by Zettwoch and Rob Steen. ISBN 978-1626728226 (softcover). 128 pages. $12.99. First Second, May 2019. This one came out in 2019, but I missed it. As much as I dig publisher First Second, I’ve skipped over Science Comics, their didactic middle-grade nonfiction series on topics ranging from dinosaurs to robots, rockets to trees. I should have been paying attention, since the series, launched in 2016, has yielded nineteen books (and counting) and looks like a solid hit. Under editors Casey Gonzalez and (now just?) Dave Roman, Science Comics has welcomed diverse artists and writers, yet the books are strongly branded, sharing a common dress and size (128 pages). Collectively, the series is quite an editorial achievement, as opposed to the creator-driven work First Second usually champions. I suppose that’s one reason I’ve stayed away — but also, I admit, I share the general distrust of children’s informational nonfiction, a critically unloved genre despite outstanding work by creators like David Macaulay (and despite how much time my family and I have spent poring over DK Eyewitness Books). Expository nonfiction for young readers is often slighted as functional, utilitarian stuff, and it’s true that nonfiction books of the Baby Professor type — mechanical and unlovely — are everywhere. I tend to look askance at books that ignore or instrumentalize the pleasures of character and plot. So it took a great cartoonist to get me to try, at last, Science Comics: Dan Zettwoch. I first read Zettwoch in the avant-comix anthology Kramer’s Ergot, then followed him to his first graphic novel, the neglected Birdseye Bristoe (2012), and to Amazing Facts and Beyond (2013), a bundle of mock-didactic, believe-it-or-not strips in collaboration with Kevin Huizenga. Zettwoch’s work is distinctive and, for me, always a draw. He is the master of the cutaway diagram, the cartoon schematic, the absurd yet precise infographic: a successor to both Rube Goldberg and Robert Ripley. Somehow, he manages to be meticulous and loopy at the same time. What’s more, his work often pays tribute to bygone technologies by showing just how they worked. Zettwoch’s cartooning peers into the mechanics of things, rendering them with clarity and joy — so an informational comic about cars would seem like a natural for him. It is. While Science Comics: Cars boasts a few recurring characters who age over the course of the book, it’s not a character-driven narrative; unlike, say, a Magic School Bus adventure, or (I gather) some other Science Comics, it’s not framed as an individual or group journey. The recurrent figures are reminders of the book’s historical through-line, but mainly Cars is a workout for Zettwoch the diagrammer. Though automotive history gives the book an arc and shape, Cars comes closer to encyclopedic Eyewitness style than to a graphic novel. It’s a reminder that comics do not always need traditional strong “storytelling” in order to engage us the way stories do. The book may be organized thematically but coheres graphically. Zettwoch divides the book into four chapters, or “strokes,” named for the modern internal combustion engine’s four-stoke cycle: Intake, Compression, Power, Exhaust. Within these, he repeats certain graphic elements that together lend a sense of order; that is, the book finds its form by braiding and varying key images, layouts, and design conceits. For example, the first two chapters both begin with accounts of historic automobile rides that serve to establish phrases and layouts that recur later. At the same time, Zettwoch throws in, unpredictably, myriad diagrams, charts, and sly jokes, and this graphic playfulness turns Cars into a series of discrete spreads that almost stand by themselves, poster-like. The book demonstrates comics’ diagrammatic nature and the power of design to cluster and clarify big gobs of information — but it also gets a bit drunk on the sheer pleasures of the page. Cars is densely informative, and a feat of design. It excels at the engineering history of autos — but less so, alas, at the social. The book wants stronger thematizing: some social and political threads that would make it, in the end, more than a compendium of wonders. The final chapter, Exhaust, hints at deeper themes, discussing fossil fuels and noxious emissions; belatedly, it suggests the damage automobiles have done to the environment (the globe is shown wreathed by auto exhaust). I figured I was being set up for a reflection on the harm as well as advantages bred by cars — but, no, Zettwoch skitters in other directions, devoting four pages to an insanely detailed chart of trucks, another spread to “Weird Cars,” and then other pages to the histories of car horns, car stereos, etc. A final section covers electric cars and the possibility of driverless cars but gives no sobering sense of the challenges posed by car culture and our reliance on personal vehicles, no sense of ecological or social consequence. Nor does the book deal in detail with automotive safety. It’s as if it can’t face up to harder issues. Instead, it’s a blithe valentine to cars that any gear monkey could love. I get a sense of failed follow-through and of implications left unexplored — that is, I found the book’s finale disappointing. To his credit, Zettwoch’s version of car history is fairly inclusive, honoring women as engineers and innovators and spotlighting non-white figures as well. The book offers a bright, affirming view of a shared car culture. Yet Cars does not come to terms with what the overabundance of autos might mean for our common future. Zettwoch’s love of automotive engineering comes through, but the “science” part of the project feels incomplete without reckoning on the environmental impact of automobiles. Road not taken? Opportunity lost, I'd say. That said, Cars remains a dazzling exercise in show-and-tell, a master class in comics as diagramming and design. Though it may not quite add up, it overflows with ingenuity and pleasure. As it turns out, Science Comics can be interesting comics indeed. I’ll read more, with hope.

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed