|

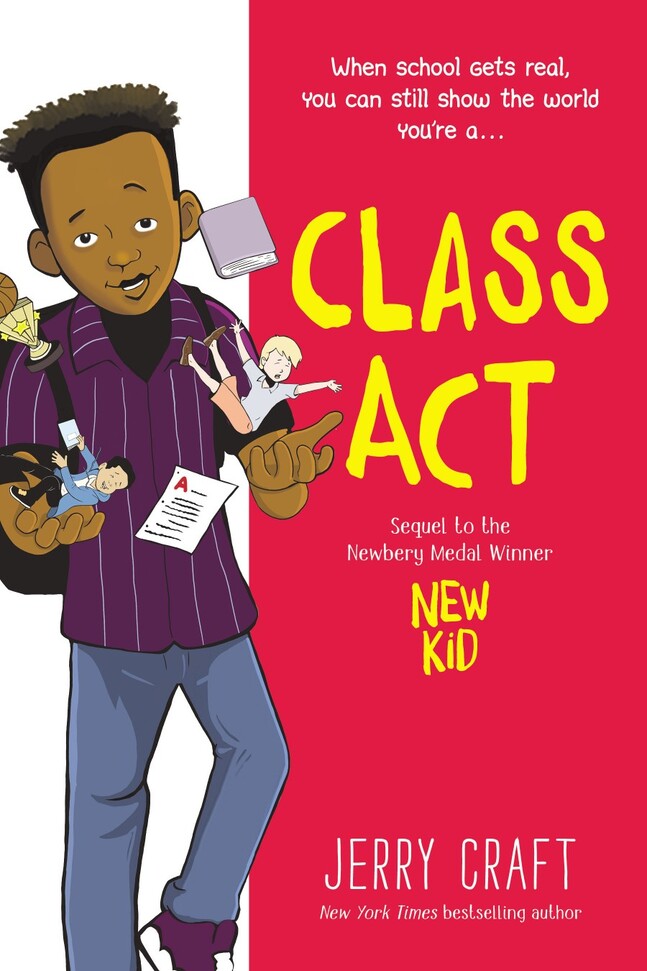

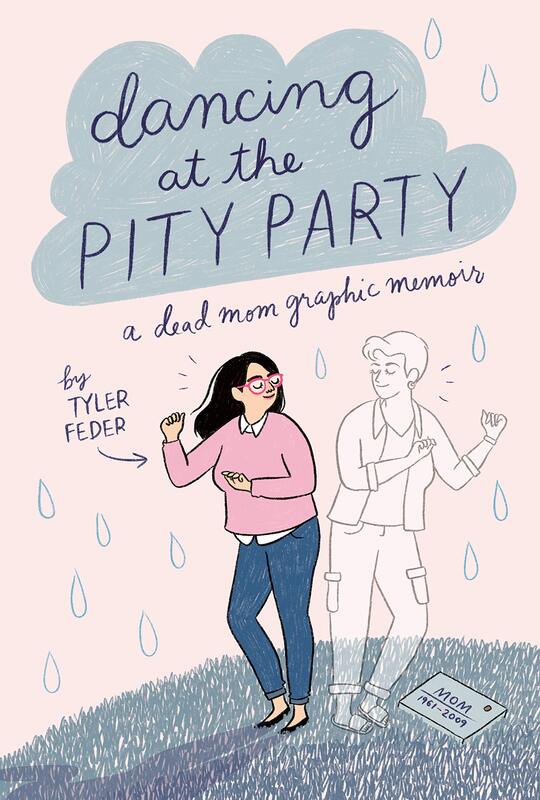

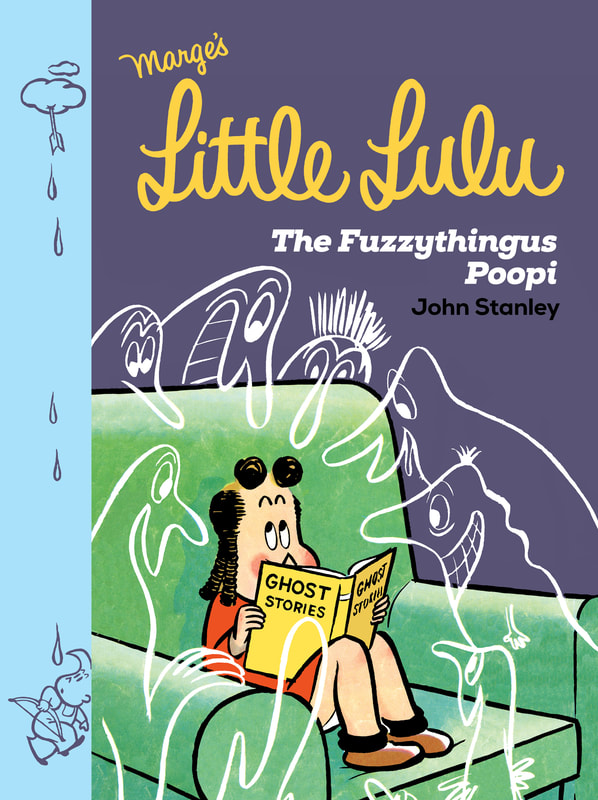

Class Act. By Jerry Craft. HarperAlley / Quill Tree Books, 2020. ISBN 978-0062885500, $US12.99. 256 pages. Billed as a “companion” to Jerry Craft’s Newbery-winning New Kid, Class Act is actually a direct sequel, following Jordan Banks and his schoolmates into the next year, but this time focusing less on Jordan and more on his friend Drew. The opening pages go to Jordan, and again his work as a budding cartoonist punctuates the story, in the form of comic strips notionally drawn by him—but Drew’s challenges, as a Black scholarship boy raised by a hard-working grandmother, soon take center stage. Drew’s pained awareness of class difference tests his friendships with Jordan and their affluent White schoolmate, Liam, and the plot tracks the awkward social negotiations among the three of them. Once again, Craft’s kids, brave and self-knowing, navigate the minefields of race and class, dogged by an inescapable sense of the things they don’t have in common; once again, their teachers are fumbling and oblivious. This time, Craft satirizes the inane efforts of their school, the tony Riverdale Academy, to extol “diversity”: teachers are dispatched to a conference called the National Organization of Cultural Liaisons Understanding Equality, and the school makes a failed effort to “adopt” a sister school whose working-class students of color don’t know what to make of Riverdale’s privileged, “bougie” atmosphere. As in New Kid, Craft observes all this in an amused, good-humored way, while never forgetting that difference can make all the difference. One tense scene depicts Jordan’s father being stopped by a White cop when driving in Liam’s posh neighborhood; moments like that affirm that Craft is playing for keeps, drawing out humor from real pain. Class Act, then, is smart and careful as well as high-spirited – though its story, I think, is more diffuse than that of New Kid, its stakes not quite as clear. (It would help to reread New Kid just before reading this one.) The book is busy and teems with in-jokes, including nods to comics and children’s book authors; sidelong gags are everywhere, to the point of distraction. More impressive is Craft’s diverse cast of distinctive, well-defined kids, many of whom get moments in the spotlight; they actually talk to each other, in courageous, meaningful ways, and Craft understands the subtle dynamics among them. You can tell he likes them. I confess that the art, with its jumbled, cut-and-paste style, clip-art elements, and CG backgrounds, put me off at first (I felt the same about New Kid). The work has an overbusy finish that mixes cartoony flatness with gradient coloring – an uneasy compromise. But Craft builds smart pages, and his socially engaged storytelling, once more, rings sharp, wise, and true. Dancing at the Pity Party: A Dead Mom Graphic Memoir. By Tyler Feder. Dial Books, 2020. ISBN 978-0525553021, $US18.99. 208 pages. Tyler Feder’s mother Rhonda Feder (née Hoffman) died of cancer when Tyler was nineteen, more than ten years ago. This memoir recounts Rhonda’s illness and death, her funeral, and the enduring sadness that has been part of Tyler’s life ever since—sometimes a still-raw, lacerating grief, sometimes a bittersweet nostalgia. That may sound just about unendurable: a self-pity party indeed. But what this book really does is pay homage to Rhonda Feder, evoke her particular, idiosyncratic self, and capture the way profound memories, very specific and odd memories that no one else could understand, arise unpredictably from quirky particulars and chance encounters. Yes, the book depicts, in fact enacts, grieving as a process, one that never quite ends, but it does so with verve, comic frankness, and surprisingly many laughs. In fact, at first, in the book’s opening pages, I wasn’t ready for Feder’s almost nonstop humorous flippancy, her many comic asides, satiric observations, and zingers. This sort of larking around in the shadow of death seemed like the very definition of Too Soon (although her mother died so long ago). To me, Feder’s approach at first felt too self-involved. But soon, very soon, the book crafts a precise portrait of Rhonda as a personality, lovingly remembered in all her quirks, the emotional, mental, and physical subtleties that made her who she was. Her eccentric liveliness, and that of her family, come through strongly, and Feder, in an unassuming and uncluttered style, balances deep sadness and irrepressible good humor, in a lovely, unforgettable tribute. Helpfully didactic at times (“Dos and Don’ts for dealing with a grieving person”), the book is mainly witty, personable, and compulsively readable—a remarkable example of how art, as Feder says, can “turn the crap into something sweet.” Little Lulu: The Fuzzythingus Poopi. By John Stanley, with Charles Hedinger, Irving Tripp, et al. Edited by Frank Young and Tom Devlin. Drawn & Quarterly, 2020. ISBN 978-1770463660, $US29.95. 276 pages. Lovingly edited, gorgeously designed, this second volume in Drawn & Quarterly’ deluxe hardcover Little Lulu series reprints more than thirty stories and strips, and a score of beautiful covers, that ran in the Dell comic book series circa 1949-1950. Written and laid out by John Stanley, these brilliant, economical, tightly wound comics were among the best of their time. They hold up well. Much has been said about Lulu as a feisty feminist icon who gets the drop on the sexist, obtuse, often mean-spirited boys in her neighborhood, and that’s true (the book’s introduction by Eileen Myles underscores that point); I was also struck, though, by the notes of human vulnerability and doubt in her characterization, by the signs of frailty and uncertainty that Stanley’s heroes often show. Lulu can be bullied, and Lulu can be hurt, but that makes her victories all the sweeter—she has real character. Stanley packs a surprising amount of human complexity into these condensed fables and gags. The tales are often absurd, sometimes satirical (such as “The Old Master,” a takedown of the art world), and always exquisitely timed, with gags and payoffs that depend upon very precise rigging. D&Q’s Lulu series is one of the best things happening in comics right now, even though the comics themselves are old. Drawn & Quarterly provided a review copy of this book.

0 Comments

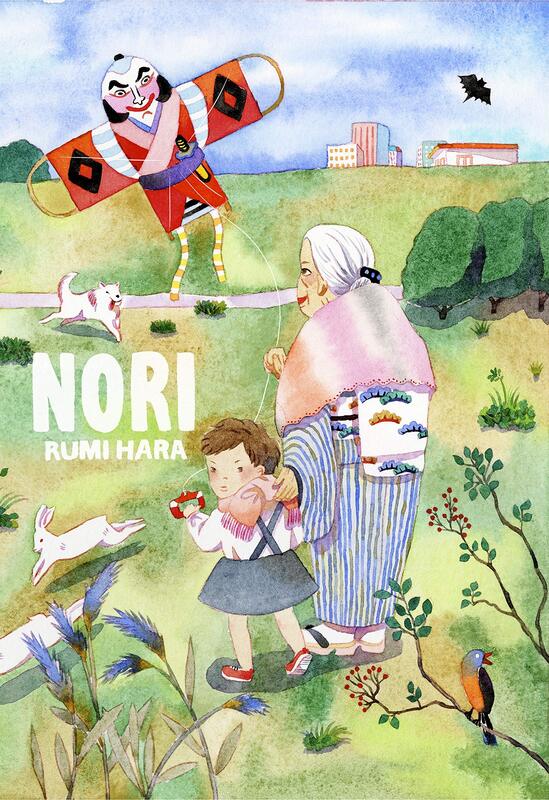

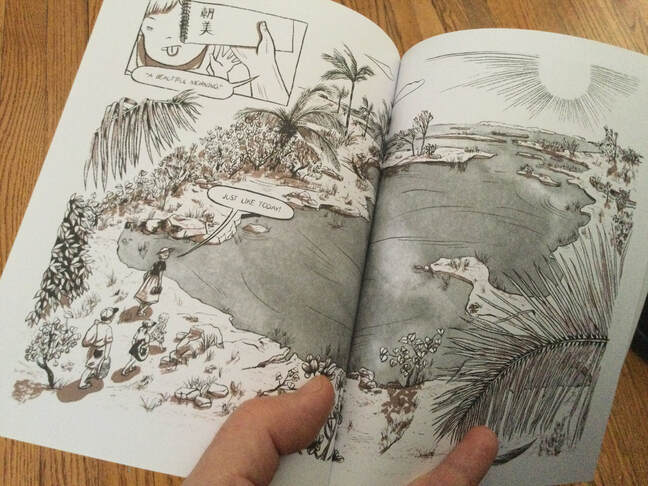

Nori. By Rumi Hara. Drawn & Quarterly, 2020. ISBN 978-1770463974, $US24.95. 228 pages. Collecting a series of minicomics begun in 2016. I regret not reading Nori sooner. It’s great: a poetic, beautifully observed portrait of one Japanese girl’s (and her grandmother’s) life, unforced, elliptical, and deeply personal. Sadly, this sort of evocative and searching book often gets dismissed by proponents of children’s books as too confusing or difficult (I know—I’ve been in quite a few conversations like that). Rumi Hara’s tale, seemingly semi-autobiographical, recalls a mid-1980s Japanese girlhood of a particular kind, in a scruffy, organic style that, for me, calls to mind Debbie Drechsler, early Lynda Barry, or Henrik Drescher. There's a similar fascination with texturing, in this case achieved through a versatile dry-brush technique that lends mood and specificity to each scene (Hara reportedly works on handmade paper, and her surfaces have a kind of nap, or nubbliness, a delicious roughness). Graceful use of a different spot color in every chapter imparts added flavor and also an overall sense of structure. I found Hara’s pages a bit disorienting at first—so rich are they—but man are they beautiful, and transporting. There are enchanting spreads here that just carry me away. Noriko, or Nori, an energetic girl of about four or five, is never disciplined out of her own free self, and remains, throughout, stubborn and even volatile, at times perhaps a bit of a pill, but really a delight. Her spirits are never sacrificed for some insufferable didactic point about maturing or becoming less of a challenge to grownups. Thank goodness. Nor does she just stand in for “childhood” as a vague state of freewheeling, unworldly innocence. She and her world are too particular for that—again, thank goodness. I grew to love this specific girl and her patient, but not over-idealized, granny, who in effect mothers Nori while the girl’s parents are busy working, working. This is a soulful book, empathetic and unpredictable, without obvious designs on the reader. Hara's storytelling takes an outside observer’s view most of the time, not giving us too-easy access into Nori’s (or anyone’s) thoughts, and sort of ambling from one thing to another, or so it seems, without obvious crises or problems to solve. But then bursts of dreamlike fantasy, brief and powerful, intervene, showing Nori's thoughts as she communes with her environment or works out her own fantastical logic. At those moments, Hara takes us in deep, but without ever showing her hand. We get glimpses of a magical but not overly sweet inner life; there's a touch of the uncanny as well (Hara says, "I like stories that have a little creepiness to them, like old folk stories that are simple but mysterious"). And as it turns out, the stories, which at first seem to have a shaggy-dog waywardness about them, are insinuating, carefully crafted, smartly rounded and complete, with levels and levels of implication and (if you care to reread and ponder) symbolism. Seeming threats turn into affirmations; the uncanny becomes lovable, yet never saccharine. I particularly enjoyed the long, ambitious story in which Nori and granny unexpectedly win a trip to Hawaii and have a wonderful, though complicated, visit there. Writing and art are both electrifyingly good here. I didn't get to read this, one of the best books of 2020, until a week into 2021. For shame! Most highly recommended. Drawn & Quarterly provided a review copy of this book.

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed