|

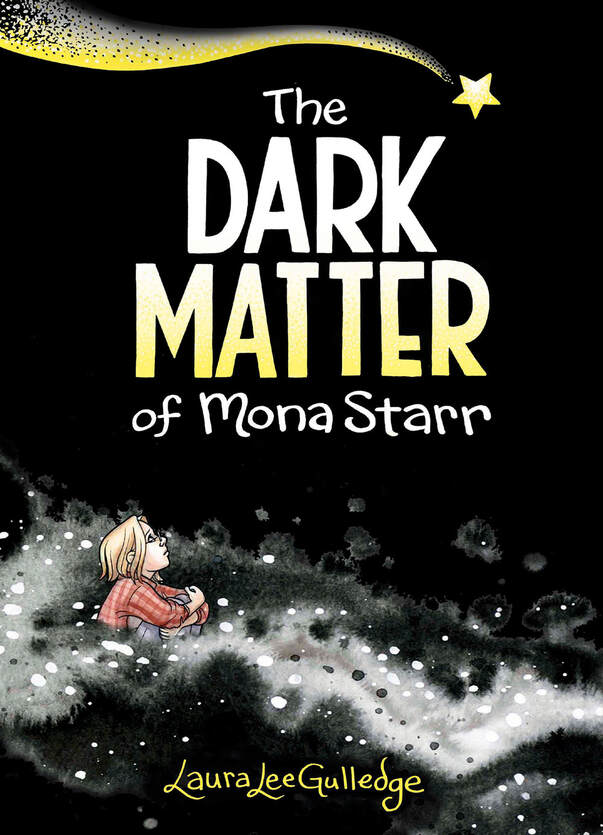

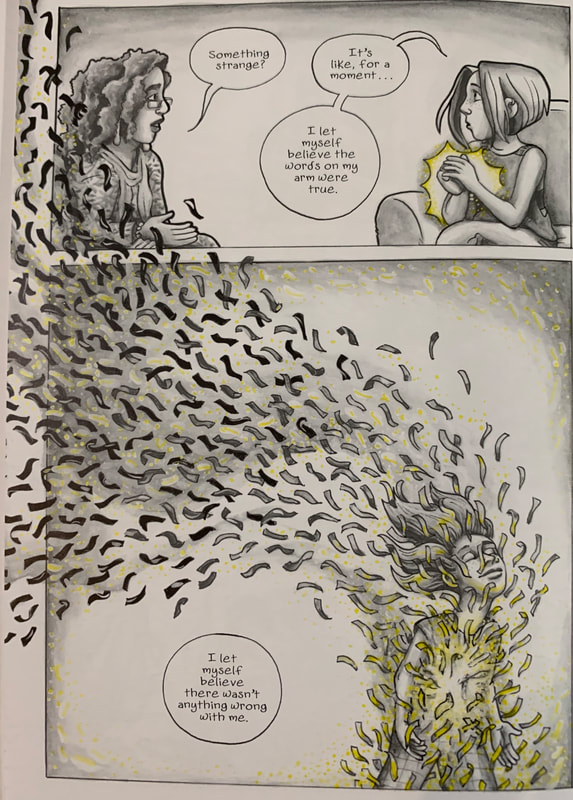

The Dark Matter of Mona Starr. By Laura Lee Gulledge. Amulet Books/ABRAMS, 2020. ISBN 978-1419742002, $US14.99. 192 pages. In this semi-autobiographical novel, Mona, a high-schooler and artist who suffers from depression, undertakes a self-study to better understand her needs and triggers and fashion a "self-care plan." Though a loner by temperament, she learns to think outside of herself and recognize loving relationships and creative collaboration as important resources in her life. With the help of her counselor, parents, and friends, Mona chooses an ethic of community and participation, sharing her aesthetic gifts and inspiring others to do the same. Looking beyond herself, even as she honors her own needs, enables her to engage the world on different terms and, to some degree, counteract her depression. The novel climaxes with a community art project in which Mona and her self-styled "Artners," Aishah and Hailey, invite many of their fellow high-schoolers to collaborate in a spirit of loving community. The story's keynotes are self-love, self-advocacy, and willful optimism, and its last word (literally) is hope. Like Ellen Forney's celebrated memoir Marbles, this novel hovers between raw personal storytelling and hortatory self-help, with chapter headers that give emphatic advice, such as Turn emotion into action and Break your cycles. Author Gulledge shares her own self-care plan in the back pages, and her notes confirm that Mona Starr is indeed based on her. Artistically, the book is wildly expressive; the pages brim with visual metaphors of depression and elation, self-isolation and self-release, artistic engagement and pure joy. Depression, Mona's so-called dark matter (her mom is an astrophysicist), appears as swirling black clouds, faceless anthropomorphic demons, dark waters, black flames, and gripping hands. Moments of self-realization and delight are accompanied by stars and streaks of bright yellow: the one spot color in Gulledge's otherwise black-and-white, or rather grayscale, aesthetic. Mental landscapes — vast oceans, deep, dark wells, and the swirling cosmos — convey Mona's ever-shifting inner state. Consensus "reality" is perfused with expressionistic symbolism, and many pages leave behind real-world settings altogether. The sheer profusion of visual symbols reminds me of, say, Iasmin Omar Ata's Mis(h)adra (a semi-autobiographical account of epilepsy that is likewise braided with graphic devices signaling the protagonist's inner state). Gulledge's figures, word balloons, and symbols routinely break out of her panel grid — in fact, there is not one page that obeys a strict, unbroken paneling — and the layouts are ceaselessly dynamic. Immersive full bleeds are frequent. In short, the book is a staggering exercise in expressive drawing and page-making. Story-wise, though, Mona Starr feels a bit thin and undeveloped to me. Despite hints that other characters may also struggle with mental illness or disability, and despite the plot's emphasis on seeking "help" and community, the novel feels very much absorbed by Mona's mental state and Gulledge's exhortations to embrace one's creativity. The book feels idealized, dreamy, and self-involved; Gulledge's artistic bravura, the sheer busyness of her pages, doesn't let the depression seem real. Everything is couched in terms of artistic therapy, self-study, and a self-improvement "project." Mona's counselor is introduced at the start, before Mona's depression has manifested narratively, and the greater context is emphatically reassuring. Much of the book consists of poetic self-reflection, heightened by the overflow of visual metaphor, as if in confirmation of Mona's creative "genius" (a personality test labels her "the potentially unstable visionary type"). Familial and social complexity take second place to exploring Mona's state of mind through ravishing visuals. The singular focus on Mona's feelings and self-conception would probably be smothering in bare prose; only Gulledge's ecstatic imagery gives the story life and depth. The result is heady and interesting but, I'm tempted to say, less novelistic than an exercise in didactic self-help. Somehow, the book manages to be at once lyrical, spectacular, and a confidently crafted exercise in comics, yet also frustratingly under-done, as if Gulledge couldn't quite take distance from what is, after all, a kind of exhortative autofiction. But here's the deal: I enjoyed reading Mona Starr, and it has moments that, on re-reading, still get me choked up. The book's conclusion is calming and gratifying, and I cannot deny Gulledge's hard-won insight. I am pretty sure that some readers will be affirmed, and perhaps even forever changed, by reading this book. I wouldn't recommend Mona Starr for complex, intersubjective storytelling, but will remember its powerful evocations of feelings and states of mind, as well as Gulledge's confident artistry.

0 Comments

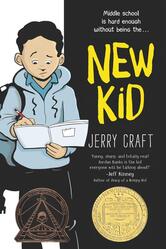

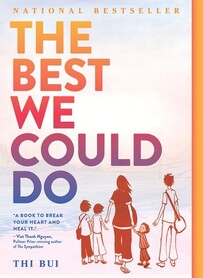

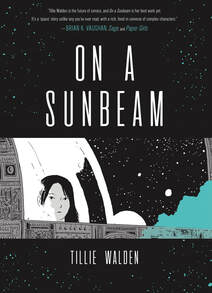

A partial list, forever in progress (every week I learn about new stuff)!(This Election Week post grew out of queries from colleagues as well as virtual teach-ins at CSU Northridge. It is very much a quick, tentative dispatch!) Below is a bunch of notes, roughly organized, about comics (especially graphic novels) that engage urgent social issues such as voting, migrant and refugee experience, racism, police violence, political activism, gender, feminism, and LGBTQ+ activism. Note that not all of these books are designated as children's or young adult books, and many contain frankly adult content. OTOH, there are some excellent young reader's books here. Besides long-form comics like graphic novels, other, shorter comics may engage such issues too, webcomics in particular. Webcomics are typically free and often address vital issues briefly and powerfully; e.g., consider the many affecting comics about living under COVID (see especially the series “In/Vulnerable,” on thenib.com, researched by reporters for The Center for Investigative Reporting and drawn by Thi Bui: https://thenib.com/in-vulnerable/). The Movement for Black Lives and the Black Comics Explosion  March, by the late John Lewis, with collaborators Andrew Aydin and Nate Powell — a memoir trilogy about Lewis’s participation in the Civil Rights Movement. One of the most acclaimed of recent American comics, and highly recommended. “Your Black Friend,” by Ben Passmore, a short satirical comic found in his book Your Black Friend and Other Strangers. Also, see Passmore’s collaboration with Ezra Claytan Daniels, BTTM FDRS, an urban horror story and satire about gentrification—it’s gross and very good! (I’d check out anything by Passmore, though he may not appeal to everyone, and some of his more underground-like work is a mixed bag. He has a new graphic novel called Sports Is Hell that I haven’t read yet. Be sure to look for Passmore’s online comics, especially on The Nib. He often engages issues of police violence and critically engages the BLM movement.) Damian Duffy and John Jennings adapted Octavia Butler’s classic novel Kindred into a graphic novel: a heartfelt piece of work about time-traveling back into the era of slavery. They have recently adapted another of Butler’s novels, Parable of the Sower, but I haven’t read it yet. Speaking of Jennings, he and fellow artist Stacey Robinson together drew the graphic novel I Am Alphonso Jones, written by Tony Medina—the story of a young Black man killed by police. This is often categorized as YA. Hot Comb, by Ebony Flowers, combines memoir and fiction: a series of short, intimate stories, many exploring the consequences of racist beauty standards for Black women. Understated, powerful. Sometimes also categorized as YA. See Jerry Craft’s New Kid for a funny, insightful middle-grade GN about being a scholarship kid of color in a tony private school. (Craft has a new book, Class Act, that I haven’t read yet.) Bitter Root, by Chuck Brown, David Walker, and Sanford Greene, is an ongoing comic book series that filters period pulp action through African American historical and cultural lenses. There are two collected volumes so far. It’s overtly political even as it dishes out monster-smashing action: an Ethno-Gothic, steampunk, antiracist adventure. Cool. (Not understated!) Great African American SF/fantasy novelists like Nalo Hopkinson, Nnedi Okorafor, and N.K. Jemisin have been writing superhero comic book serials lately. Jemisin is about 2/3 of the way through a Green Lantern series with many topical elements titled Far Sector, drawn by Jamal Campbell. It concerns race and the challenge of living in a pluralistic society (a faraway world inhabited by billions of beings of several different species). Smart, rich work. Immigrant and Refugee Experience Alberto Ledesma shares reflections from his life as an undocumented immigrant in Diary of a Reluctant Dreamer, a very personal scrapbook of sorts that grew out of a series of Facebook posts. Eye-opening for me, and poignant. Besides superheroes, Nnedi Okorafor has written a SF comic called LaGuardia that deals with immigration and nativist backlash—but on a planetary level! It’s drawn by Tana Ford. Escaping Wars and Waves, by graphic journalist Olivier Kugler, depicts Syrian refugees living in refugee camps, and is excellent. Border: A Crisis in Graphic Detail, edited by Mauricio Alberto Cordero, is a recent comics anthology about migrant experience at the US’s southern border, and a fundraiser for the South Texas Human Rights Center. Powerful stories and testimony. The Scar, by Andrea Ferraris and Renato Chiocca, is a brief but powerful treatment of the US/Mexico border. Migrant: Stories of Hope and Resilience, written by Jeffry Korgan and illustrated by Kevin Pyle, recounts personal stories of crossing the US border (I haven’t had a chance to read it yet). Thi Bui’s graphic memoir, The Best We Could Do, about five generations in the life of a Vietnamese American family, is brilliant, a great book. (Matt Huynh’s webcomic Cabramatta resonates with this: http://believermag.com/cabramatta/. So does GB Tran's book Vietnamerica.) The recent YA graphic memoir by Robin Ha, Almost American Girl, depicts a Korean American experience that perhaps invites comparison. There are quite a few graphic memoirs about the experience of immigrants’ children—see, e.g., I Was Their American Dream, by Malaka Gharib. They Called Us Enemy, by George Takei, Justin Eisinger, Steven Scott, and Harmony Becker, is an autobiographical account of the incarceration of Japanese Americans during WW2. Much to learn here. Immigration policy is discussed in Open Borders: The Science and Ethics of Immigration, by Bryan Caplan and Zack Weinersmith, though I haven’t gotten to read it yet. It’s a didactic graphic book: less story than argument. But there are many great comics like that! Comics on the Political ProcessUnfit: How to Fix Our Broken Democracy, by Daniel Newman and George O’Connor—though I’m afraid I haven’t read this yet. Drawing the Vote: An Illustrated Guide to Voting in America, by Tommy Jenkins and Kati Lacker. Comics about Indigenous LivesFor comics by Indigenous creators, see for example the anthology Moonshot, and check out publisher Native Realities: https://redplanetbooksncomics.com/collections/native-realities. In particular, the collaborations of artist Weshoyot Alvitre and writer Lee Francis IV (e.g., Sixkiller; Ghost River: The Fall and Rise of the Conestoga) have captured my attention. Look also for the anthology Deer Woman, co-edited by Alvitre and Elizabeth LaPensée. A recent scholarly collection, Graphic Indigeneity, ed. Aldama, will help here. Celebrated comics journalist Joe Sacco (who produces one stunning book after another) has just recently published Paying the Land, a book about resource extraction and energy politics, but most particularly the history of an Indigenous Canadian people, the Dene. I’ve read only the opening chapter so far (which is remarkable) but the book looks ambitious and informative. Know that Sacco is not an Indigenous author (he is Maltese-American), and scholar colleagues versed in this area have shared some eye-opening critical points with me; still, Paying the Land will surely be worth your time. Gender and Sexuality (Feminist, Queer, and Trans Perspectives)Drawing Power, edited by Diane Noomin, is a stunning anthology of stories about sexual violence, harassment, and survival. Strong, stinging, varied work there, sometimes harrrowing—a response to #MeToo. Maia Kobabe’s nonbinary memoir, Gender Queer, is tender and revelatory. You could call it a YA book, though of course its reception in YA circles has been fraught. (It's a frank depiction of, among other things, gender expression and sexual exploration — so, well, let's just say that some Amazon customers disapprove.) Look for the LGBTQIA anthology Love Is Love, a 2017 benefit to help victims of the Orlando nightclub shooting—short comics, but often powerful, and varied in approach. Justin Hall’s No Straight Lines: Four Decades of Queer Comics is essential history. Edie Fake's Gaylord Phoenix is a mind-altering, phantasmagorical quest fantasy from a trans perspective: a mostly wordless transition fable that rewrote the way I think about comics! Highly recommended. (Be aware: this is not tagged as a young reader's book, and includes startling images of violence and self-harm as well as sexual abandon.) Disability, Graphic Medicine, and CareCheck out the graphic medicine movement, devoted to comics treatment of illness, wellness, and dis/ability: see https://www.graphicmedicine.org. Note also the prevalence of disability memoirs in comics that are not medical in focus, e.g. Cece Bell’s great children’s comic, El Deafo; or the very recent (fictionalized) YA book, The Dark Matter of Mona Starr, by Laura Lee Gulledge, about depression; or any number of webcomics about life on the autism spectrum. Kabi Nagata’s manga My Lesbian Experience with Loneliness concerns not only sexuality but also anxiety and depression. Allie Brosh’s work also addresses depression and anxiety (Hyperbole and a Half; Solutions and Other Problems). Katie Greene’s Lighter Than My Shadow depicts her life with anorexia and an eating disorder. I highly recommend Vivian Chong and Georgia Webber's collaborative memoir, Dancing after TEN, which recounts a life-changing medical crisis for Chong that robbed her of sight; as well as Webber's own solo book about literally losing her voice, Dumb. Re: aging and elder care, see such graphic memoirs as Roz Chast’s Can't We Talk about Something More Pleasant? and Joyce Farmer’s Special Exits. Just a random recommendationFor depiction of progressive activism in a near-future dystopia, basically just a few steps from our own, read The Hard Tomorrow, by Eleanor Davis. This one rattled me, and it's beautiful. One last note (preaching to the choir?)As many KinderComics readers may know, children’s and young adult graphic novels are the fastest-growing, most robust sector of comics publishing in the US. They often deal with complex immigrant or minority experience, and offer queer-positive portrayals as well. Check out anything by Mariko Tamaki, Jillian Tamaki, Jen Wang, or Tillie Walden. This publishing movement is really doing bold new things in queer representation and identity narrative.

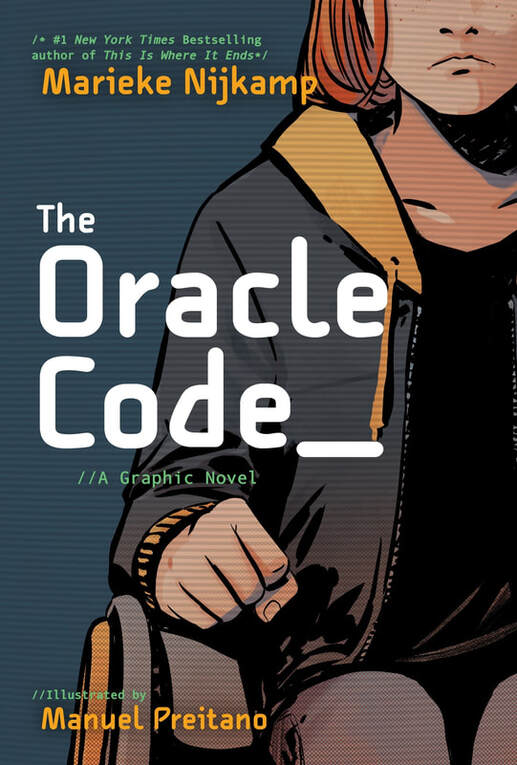

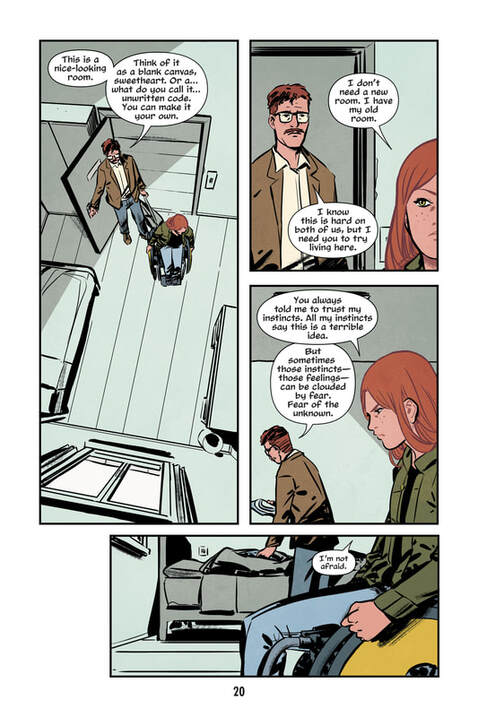

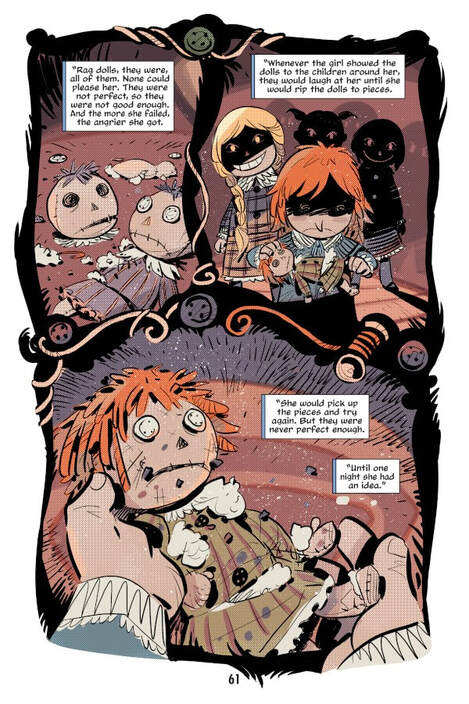

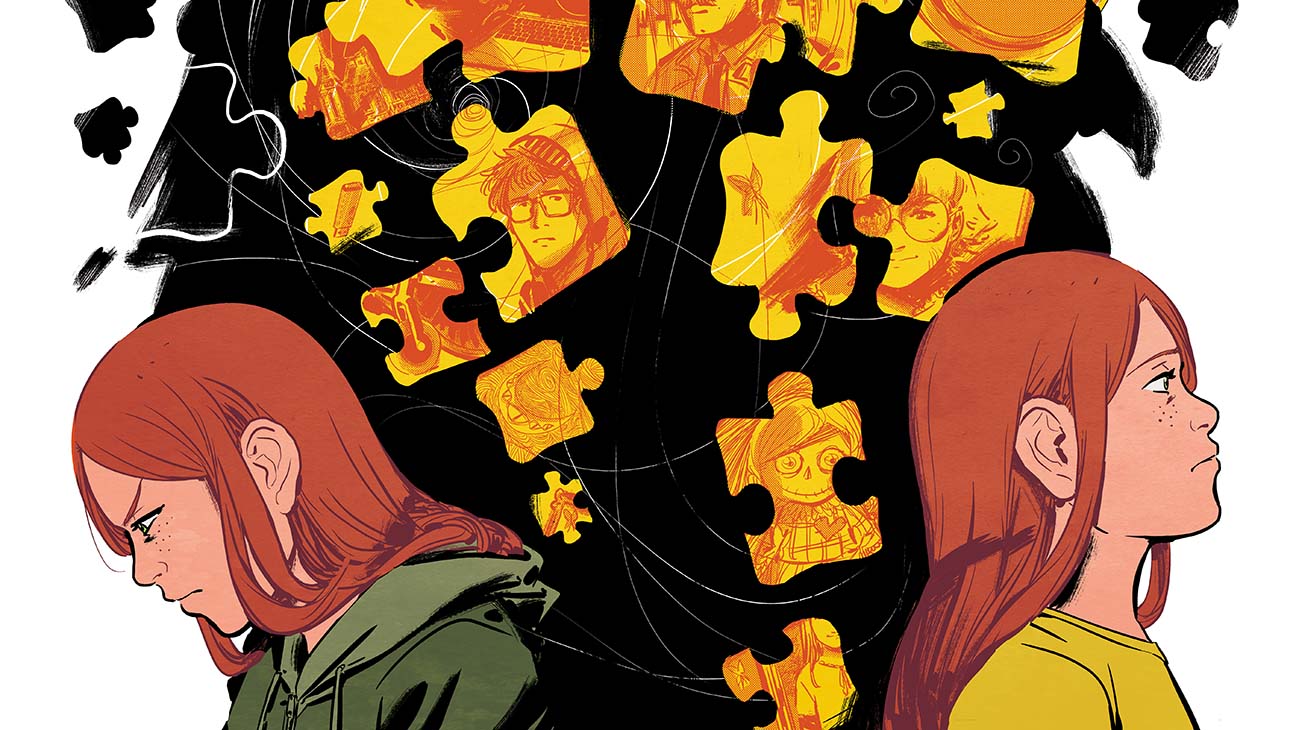

The Oracle Code. Written by Marieke Nijkamp; illustrated by Manuel Preitano; colored by Jordie Bellaire with Preitano; lettered by Clayton Cowles. DC Comics, ISBN 978-1401290665 (softcover), 208 pages. US$16.99. March 2020. (This is the second in an occasional series reviewing children’s and Young Adult graphic novels from DC. See the first here.) Paralyzed by a gunshot wound, brilliant young hacker Barbara Gordon (daughter of Gotham’s police commissioner) undergoes rehabilitation at the so-called Arkham Center for Independence — which, surprise, turns out to be a sinister place, a haunted house even, from which patients keep disappearing. Though traumatized, and at first resentful and alienated, Barbara gradually bonds with other patients, and together they form a team to unravel Arkham’s dark secret. This DC graphic novel does not appear to mesh with any version of DC continuity, and its Barbara Gordon differs sharply from previous Barbaras (Batgirl or Oracle). In fact, its DC-ness is nominal, and could be erased with a few minor edits. It’s not a superhero story in the usual sense. Rather, it’s a Young Adult thriller that follows many of that genre’s conventions: young people up against corrupt adult institutions, fighting with official powers, fighting for self-definition, testing their mettle with no outside help. It’s also grounded in an intersectional and community-oriented disability politics that makes it stand out among DC books. Writer Marieke Nijkamp is an acclaimed author of YA thrillers (e.g., This Is Where It Ends), editor of a disability-themed YA anthology (Unbroken), and advocate for greater diversity in children’s and Young Adult publishing (she served as a founding officer of We Need Diverse Books). The Oracle Code’s plot seems to have been informed by her experience living in a medical rehabilitation facility as a teenager. Her loner hero, Barbara, eventually enters into community, and, with her team, emphatically rejects the idea of being “fixed” (echoing Nijkamp’s criticisms of the trope of curing disability). The book’s politics are obvious and central, and some minor characters and relationships seem designed to make points — or to serve merely as hurdles to Barbara’s ferocious drive. The plot, I think, rushes to a too-sudden conclusion; I can see the story’s somewhat familiar shape from far off. Barbara herself, though, is a distinct character, and the book gives her time and space to be properly angry. If the book preaches, it doesn’t preach to Barbara. Also, the wrap-up wisely lets certain resolutions stay ambiguous; this is no facile overcoming narrative in which all things are made better. The book reflects on the healing value of dark stories — through a series of unsettling embedded tales, like bedtime stories — and itself does not shy away from trouble. The Oracle Code, in sum, is a designedly Young Adult novel that reflects and capitalizes on the disability politics always implicit in the Oracle character. Visually, The Oracle Code wavers between arid daytime plainness — perfect for a medical facility — and darkly atmospheric nighttime scenes. Illustrator Manuel Preitano favors a naturalism that, for me, recalls the post-Mazzucchelli work of David Aja (though without Aja’s drastic stylization and formalist invention). The intentionally limited color palette (colors are credited to both Jordie Bellaire and Preitano) pits vivid yellow-orange and nocturnal purple-blue against drab olive and icky, hospital-bland greens. Insipid, textureless rooms — like the flat, medicalized interiors we all know, presumably lit by fluorescents — clash with densely shadowed scenes defined by slashing swathes of black and vigorous dry-brush technique. Bright jigsaw puzzle pieces stand out against the general gloom and serve as a braided visual device: a multivalent symbol that variously signifies trauma, fragmentation, reassembly, accomplishment, and, of course, mystery-solving. The layouts are dynamic, shifting, yet steadily rectilinear, except for the embedded “bedtime” stories, which boast curving, swirling panel shapes and a contrasting, cartoonish style. This novel is, as far as I know, Preitano’s longest sustained work for the US market (he has also worked on the series Destiny, NY and several comics for Zenescope), and departs from the sometimes lurid retro aesthetic of his illustrations for the Vaporteppa fiction line, in his native Italy. This looks like a big step forward for the artist. On balance, The Oracle Code shows the potential of YA fiction that happens to be set in DC’s story-world. It’s more self-contained, and more attuned to the conventions of YA fiction, than I had expected. To me, these are good things. One thing gets to me, though: despite the signs that this book is a rather personal work for Nijkamp, it is copyrighted solely in the name of DC Comics — that is, it’s work for hire (though it bears about as much resemblance to prior Oracle stories as, say, Neil Gaiman and company’s Sandman bore to prior Sandmen). I think that’s a shame, and, honestly, this is one reason I have not been able to muster great enthusiasm for DC’s work with YA and children’s authors. As long as DC graphic novels are centered on company IP and the creators are wholly dispossessed of any equity in the work, as long as DC persists in these damaging comic book industry practices, the promise of its young readers’ line will be dampened. The Oracle Code is very unusual for a DC comic — its focus on a non-superpowered community of young women, and willingness to highlight a young woman’s anger and power, are laudable — but it’s still shackled to DC’s old way of doing things.

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed