|

Plain Jane and the Mermaid. By Vera Brosgol. Color by Alec Longstreth. First Second, ISBN 978-1250314857, May 2024. $US14.99. 368 pages, softcover. Vera Brosgol is one of my favorite artist-authors in the children's graphic novel field. She's back with a new book, her first graphic novel since 2018, and it's a doozy. Mind you, Brosgol has not been idle. These past six years, she has, by my count, written and illustrated two picture books, illustrated two more, and worked as head of story on the film Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio. Whew! I'm glad to have a new graphic novel by her. Plain Jane and the Mermaid is a feminist fairy tale about outward appearances versus inward self-worth. It's also an inventive, and occasionally spooky, phantasmagoria that takes place almost entirely underwater. Jane, a "plain" young woman of apparently few prospects, dives into the deepwater world of selkies, sea monsters, and mermaids in order to rescue (?) Peter, a mermaid-stolen man with whom she thinks she has fallen in love. She hardly knows the guy, but he is beautiful, and she has asked him to marry her. Marriage is Jane's one hope, because, as the last survivor of a household without a male heir, she is about to be turned out of her home by a distant and uncaring cousin: A mysterious crone magically grants Jane the ability to survive underwater, and so Jane takes off in pursuit of her hoped-for husband. In the meantime, Peter is wooed and pampered by a trio of mermaids, little suspecting what they may have in store for him. Things turn dark(er) when Peter learns what it is that mermaids actually do with humans, but meanwhile Jane develops a comical yet genuine friendship with a seal who turns out to be a selkie, and her plainness (if that's what it is) no longer matters. There are twists and surprises en route, and the story ends delightfully, with a sense that various dangling loose ends have been tied up, or tied together, in unexpected but apt ways. It's the kind of well-engineered book where nothing goes to waste, and small details glimpsed along the way turn out to be openings (or deepenings). Brosgol's story-world is cruel. Parents and peers judge and shame; rivals tease and bully. Plainness of face and stoutness of body are condemned. Appearances count, and mirrors are threats. Beautiful people get unearned perks and learn to rely on them, while ordinary, unlovely people are expected to scrape and crawl. Social outliers are sacrificed for the comfort of the socially advantaged. Women get the short end of most everything, and predation and hunger rule. Some readers may be taken aback by the harshness of this world, but to me it seems honest enough. Some may be alarmed by certain terrible comeuppances that are meted out. The story is tough. Moreover, some undersea scenes are scary, as when, on a sunken ship, corpses come groaning to life and close in on Jane, or when a giant anglerfish almost snaps her up in its jaws, or when a mermaid bares her teeth. Brosgol isn't scary in quite the same way as, say, Emily Carroll (whose take on mermaids is positively terrifying); she pushes only a little at what middle-grade books usually allow. But she does push. Me, I love these moments of risk-taking. Her graphic novels always play for keeps, and that wins me over. So, Plain Jane is a recognizable Vera Brosgol book. Yet Brosgol deserves credit for making each book look and feel a little different. Plain Jane doesn't look that much like Anya's Ghost or Be Prepared (they don't look that much like each other, either). This one feels a bit rawer in the rendering, I'm guessing deliberately, but at the same time uses a full color palette, courtesy of color artist Alec Longstreth — a great cartoonist in his own right, and a great graphic novel colorist. He does a lot of heavy lifting here. (It's a shame Longstreth's name isn't on the title page where it should be. Though the back matter reveals some of the coloring process, and Brosgol praises "Alec" effusively, you have to read the fine print to find his full name.) Despite surface changes in style, Plain Jane boasts Brosgol's usual distinctive character designs, expert timing, and gift for small shocks. This is clear, classic cartooning. The book is not the revelation that Anya's Ghost was, but it's thrilling. Its roughly 350 pages pass too quickly, a fierce, lovely dream. The final affirmation of Jane's self-worth is not surprising — in that sense, the book ends where most of us would want it to end — but the trip is full of little gemlike touches. Vera Brosgol really is a gift, you know?

0 Comments

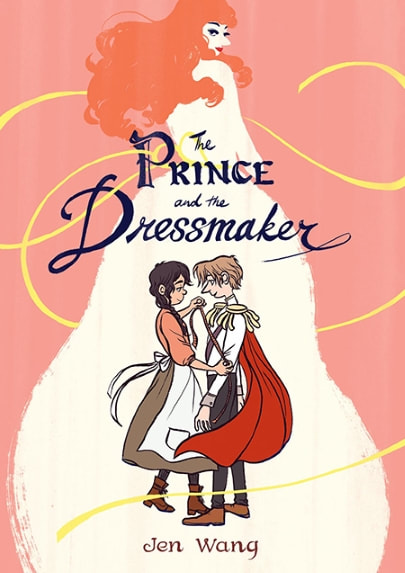

I'm honored and delighted to be giving a talk as part of the Los Angeles Public Library's West Valley Big Read focusing on Jen Wang's graphic novel, The Prince and the Dressmaker (the first book I ever reviewed here on KinderComics). Jen Wang is one of my favorite cartoonists, and The Prince and the Dressmaker one of my favorite books of the 2010s. In fact, I'd say it's one of my top ten graphic novels of the past half-decade. So doing this talk is a real treat! As the above flyer says, the talk is happening at the West Valley Regional Branch Library on Saturday, July 23, at 11:00 a.m. LAPL has more information about the talk here: https://www.lapl.org/whats-on/events/lets-talk-graphic-novels. Readers, I hope some of you will be able to make it — and please help spread the word!

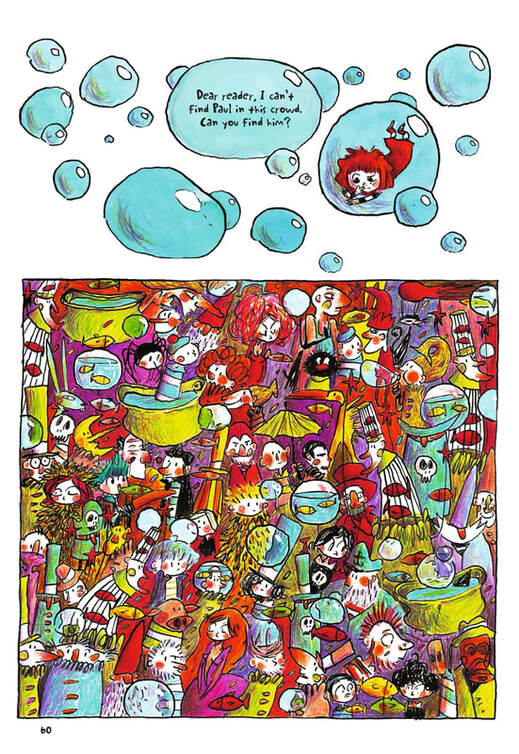

The Runaway Princess. By Johan Troianowski. Translated by Anne and Owen Smith; designed by Patrick Crotty. RH Graphic, ISBN 978-0593118405 (softcover), $12.99. 272 pages. January 2020. The Runaway Princess, a giddy, self-aware romp, celebrates doodling, play, and spontaneous worldbuilding. Its title and cover may suggest a feminist fractured fairy tale of the Princess Smartypants variety, but it’s really a Baron Munchhausen sort of yarn, a happy riot whose main lesson is pleasure. Not so much a deliberate novel as a spree, it showcases author Johan Troianowski’s freewheeling cartooning while riffing on familiar stuff. The first release under RH Graphic, Random House’s new comics imprint, The Runaway Princess translates Troianowski’s French series Rouge (2009-2017). The Rouge of the original becomes Robin here; she’s a wayward young adventuress with a touch of Little Red Riding Hood but also Pippi Longstocking. The world she travels is a vehicle for exuberant drawing and vivid, crayon-and-ink coloring. It’s also chockablock with drive-by homages to children’s literature, from classic fairy tales to Alice to The Wind and the Willows. Essentially, The Runaway Princess collects three rambling quests that consist of hide-and-seek, maze-walking, and casual discovery. In the first, Robin traverses a dark and threatening wood, where she befriends four lost kids, all boys, whom she leads out of the wood, to a strange city and festival. There some of the kids get lost again and have be found. In the second tale, Robin and the boys discover an underground world, where Robin befriends a witch, until the tale takes a darker, Hansel and Gretel-like turn; more hiding and chasing ensue. In the third, Robin and boys are cast away on an island, where a benevolent explorer introduces them to the culture of the Doodlers: small creatures who make art. Treasure-hungry pirates attack, and again the plot affords plenty of frantic running around. Notably, the book includes self-reflexive, interactive pages that invite the reader not just to read but to do things: solve mazes, shake the book, etc. That is, The Runaway Princess is a game of sorts; the book knows that it’s a book, and invites us to have fun with that fact. If Troianowski’s loose, scribbly style recalls Joann Sfar or Lewis Trondheim, his metatextual play recalls Fred’s classic Philemon series: as the plot bounces from one craziness to another, there’s little sense of danger or poignancy, more a benign, Fred-like absurdism and self-awareness. Troianowski excels at weird places—City of Water, Island of Doodlers—and favors graphic playfulness over tight logic, but it’s the direct appeals to the reader that make it work. Though The Runaway Princess would be at home alongside Philemon, or, say, Sfar’s Little Vampire, it lacks the philosophical weight of Fred and odd tenderness of Sfar, and sometimes reproduces Eurocentric, colonialist clichés (as in the ethnological Doodlers plot). Yet the book fizzes like a rocket, and cheerfully celebrates creativity (in this, it resembles, say, Liniers’s Written and Drawn by Henrietta). In sum, it’s is a breezy, inventive launchpoint for RH Graphic, and recommended.

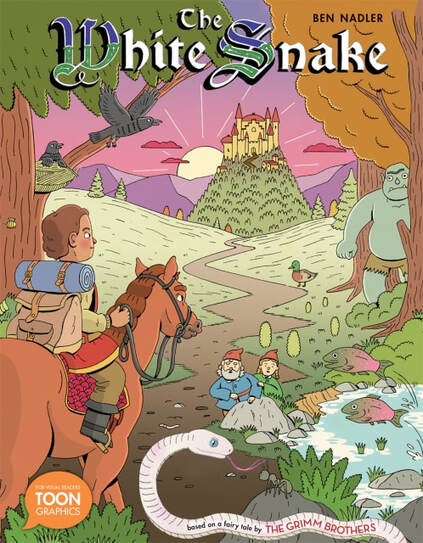

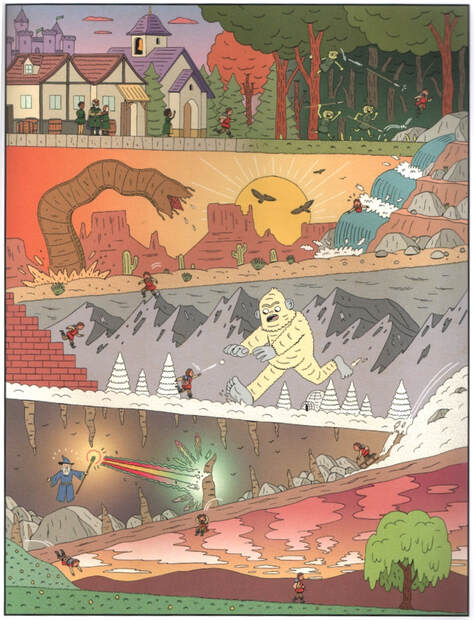

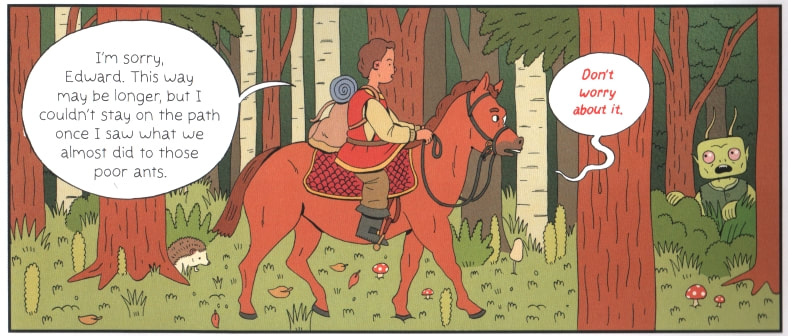

The White Snake. By Ben Nadler; based on a fairy tale by the Grimm Brothers. Edited by Paul Karasik and Dashiell Spiegelman; book design by Françoise Mouly. TOON Books, 2019. ISBN 978-1-943145-37-9 (hardcover), $16.95 ; ISBN 978-1-943145-38-6 (softcover), $9.99. 56 pages. Matter-of-fact inventiveness, marginal drollery, and a heaping helping of weirdness are the main ingredients of Ben Nadler's The White Snake, a winningly eccentric update of a Grimm Brothers fairy tale. It's a cool book. The story is about the getting of wisdom through acts of eating—literally, by taking bites of things. Its logic is less literal than symbolic, a matter of telling parallels and a neat sense of karmic payback: its hero helps various creatures who then help him in return, making it possible for him to overcome various trials. In a sense, the hero wins out because he listens and because he cares—he has a compassionate feeling toward the world around him. This helps when he is set impossible tasks that must end in either victory or death. The upshot of those tasks is that our hero must compete to win the hand of, you guessed it, a princess—but Nadler takes pains to update the tale so that the princess is no shrinking violet, but a smart leader who helps set things in motion in the first place. They become a team, and she the ruler of the land. The story ends with enlightenment (a blast of cosmic insight) and a not-too-crazy happily-ever-after that melds fairy-tale logic with progressive values. The fated parallels and connections so typical of Grimm fairy tales are preserved, the unselfconscious strangeness of folktales maintained, even as the book weaves in current feminist and environmentalist concerns. This is a considered adaptation, helped quite a bit, I gather, by the editorial input of Paul Karasik and TOON's Françoise Mouly. The results are wise as well as cool. The book’s visual style is sharp and clean, almost aseptic, with pristine lines that suggest a yen for the Ligne Claire tradition. Yet at the same time there’s an anxious, post-punk quality that, for me, recalls Mark Beyer or Henrik Drescher, and a trace of eccentric gothicists like Edward Gorey and Richard Sala. Lane Smith’s early, Klee-like work comes to mind too—also Adventure Time, and perhaps Klasky Csupo animation. Which is to say that Nadler’s mark-making, though spare, retains some nervous tics; his pages, though restrained in layout and admirably clear, hint at art-comics affinities. The look here is less the Ivan Brunetti-esque schematic minimalism of Nadler's self-published risograph comic Sonder (in which bodies tend to be clean, geometric forms) and closer to the illustrative lushness of his first book, Heretics! (a graphic history of modern philosophy, co-created with his father, philosopher Steven Nadler). But we are still a long way from naturalism here. The characters are a bit stiff, as opposed to supple; faces are schematized; action is coolly posed. The frequently oblong, page-wide panels tend to stage events and travels as if they were happening in front of a scrolling panorama. The total look implies both stability and an unrepentant oddness—well suited for the blithe absurdity of the story and its deadpan embrace of the weird. Along the way, Nadler enlivens the pages with a wealth of curious detail. There’s a great deal of whimsical chicken fat, and odd critters abound. Right from the start, you can tell that Nadler intends to draw out and reward attentive readers with all sorts of sidelong business. The result is a distinct and pleasurable graphic world, crawling with fun stuff. Like Jaime Hernandez's The Dragon Slayer (another folklore-inspired TOON Graphic "for middle grade visual readers," i.e. experienced comics readers), The White Snake is less a solo act than a group effort. It appears to have been carefully curated by TOON's editorial director Mouly and guided by input from editor Karasik, who supplies the educational back matter: a brief essay on folktales, including a frank discussion of how the book has adapted and revised the Grimms' version. All this contextualizes the book without interfering with its story or damping down its quirkiness. The result is delightfully odd—another TOON title yoking together children's literature and alt-comix aesthetics. It has put Ben Nadler on my radar, for which I'm grateful, and joins a growing smart set of folk and fairy tale-based comics. Recommended!

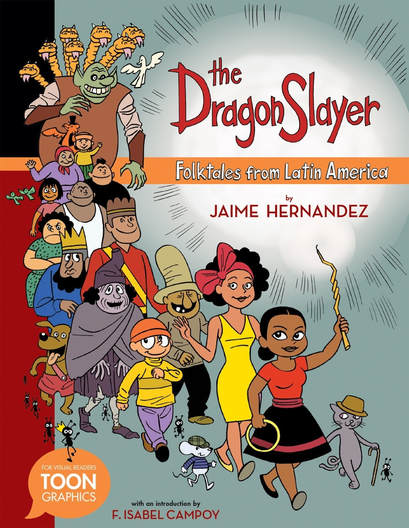

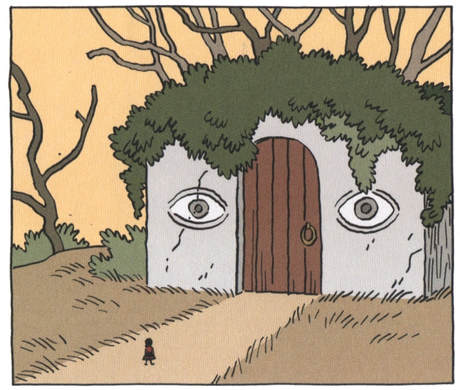

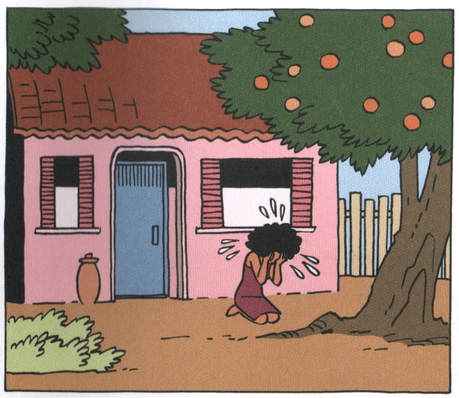

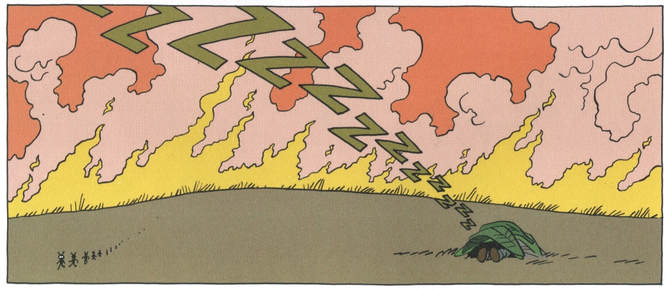

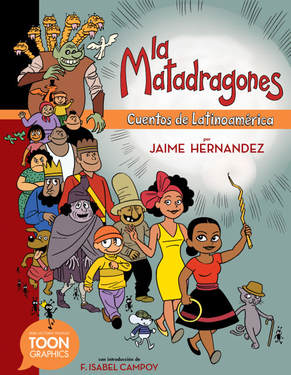

The Dragon Slayer. By Jaime Hernandez. TOON, 2018. Hardcover: ISBN 978-1943145287, $16.95. Softcover: ISBN 978-1943145294, $9.99. 40 pages. A Junior Library Guild Selection.Jaime Hernandez, one of the world's great cartoonists, is as lively and influential a comic book artist as you could hope to find. He has changed many readers' and artists' lives. His work on the Love and Rockets series (1981-now), in tandem with his brothers Mario and especially Gilbert Hernandez, proved that there was life and juice and relevance in the serial comics magazine, beyond even what many fans of the medium had dared hope. The punk, Latinx, and queer-positive aesthetic of L&R, along with its serious, in-depth storytelling and formal risk-taking, made for a revolution in comics, and Jaime Hernandez has deservedly been called one of the masters of the medium. The Dragon Slayer is not his first comic for children, as he's done a few short pieces for children's anthologies. Nor is it his first comic based on folklore: seek out for example "La Blanca," his version of a ghost story he heard from his mother, which he did for Gilbert's all-ages anthology Measles No. 2 back in 1999 (Gilbert too has made folk and family lore into comics: dig his "La Llorona," from New Love No. 5, back in 1997). Moreover, children and childhood memories are essential to Jaime's work in Love and Rockets. But The Dragon Slayer is Jaime's first real children's book. I have kid [characters] in my adult comics, but they play by my rules. Now that I’m writing for children, I’m playing by their rules. I was a little nervous because now I’m speaking directly to kids and to the parents who will let them read [the book]. So Dragon Slayer is something new for him. In fact it's a quiet collaboration: the book's back matter tells us that Hernandez read through many folktales to find the three that he wanted to adapt, and in this he was commissioned and helped by TOON's editorial director and the book's designer, Françoise Mouly. Mouly's team also deserves mention: in this case, designer Genevieve Bormes, who supplied Aztec and Maya design motifs that enliven the book's endpapers and peritexts, and editor, research assistant, and colorist Ala Lee. Like most books in the TOON Graphics line, Dragon Slayer includes some discreet educational apparatus, in the form of notes and bibliography -- more teamwork. Further, the book comes introduced by prolific scholar and children's author F. Isabel Campoy, whose collaborative book with children's author and teacher educator Alma Flor Ada, Tales Our Abuelitas Told: A Hispanic Folktale Collection (2006), is credited as one of Hernandez's sources. Campoy and Ada are key contributors here. (Another key source, albeit not as clearly announced, is John Bierhorst's 2002 collection Latin American Folktales.) All this is by way of packaging three 10-page comics by Hernandez, which are a delight, and are over too soon. I could read book after book like this from Hernandez -- the premise fits him beautifully. Hernandez has said that he liked the "wackiness" of these stories, and they do have that absurd-but-perfect, unquestionable quality of many folk tales: a sense of symbolic rightness and fated, almost-inevitable form in spite of the seeming craziness of their plots. Things happen that are preposterous and unexplained but just seem to fit, to click, because of the tales' use of repetition, parallels, rhythmic phrasing, and ritual challenges: stock ingredients, in anything but stock form. These folkloric patterns make the tales complete and rounded no matter how nonsensical they might appear at first. In crisp pages that rarely depart from a standard six-panel grid, Hernandez delivers the stories straight up, without any rationalizing or ironic distance, in clean, classic cartooning that communicates without breaking a sweat. Jaime is a master of seemingly guileless and transparent, but in fact subtle and artful, narrative drawing, and The Dragon Slayer does not disappoint. This has been billed as a "graphic novel," but it's no more a novel than other splendid TOON books like Birdsong, Flop to the Top, The Shark King, or Lost in NYC. What it is is a charming comic book that whets the appetite for more. Hernandez's cartooning benefits from the book's folkloric and scholarly teamwork, but the main thing is that the comics are marvelous. The title story, a feminist fairy tale with a light touch, focuses on an unfairly disowned youngest daughter who slays monsters and solves problems: a real pip. "Martina Martínez and Pérez the Mouse" (adapted from Ada's text) is an absurd story of marriage between a woman and a mouse, until it becomes a wise fable about panic and grief. "Tup and the Ants" is a lazy-son story in which the (again) youngest child proves his mettle with the help of a hill's worth of hard-working ants. All three comics surprised me and made me laugh out loud. I could call the book an anthology of lovely moments. It suffers no shortage of arresting moments -- panels that leap out: But what really makes these panels lovely is that there is no grandstanding in the art, only a terrific economy in visual storytelling: a streamlined delivery that carries us far, fast. Context is everything, and the book is not so much excerptable as endlessly readable. In short, The Dragon Slayer is a great book for Jaime Hernandez and for TOON, and one of the best folktale and fairy tale-based comics I've seen. I confess myself puzzled by its labeling as a TOON Graphic, which in the TOON system implies an older, more experienced comics reader, as opposed to TOON's Level 1, 2, and 3 books for beginning or emerging readers (I don't see this as a more complex comics-reading experience than, say, some of the Level 3 titles). But I do appreciate the oversized (7¾ x 10 inch) TOON Graphics format, which gives Hernandez a larger space to work in, more like that of a comics magazine. That suits his drawing and pacing. In any case, The Dragon Slayer is a sweet, short burst of smart, loving comics, and comes highly recommended. PS. A Spanish-language edition, La Matadragones: Cuentos de Latinoamérica, is also available in both hardcover (ISBN 978-1943145300) and softcover (ISBN 978-1943145317), priced as above. TOON provided a review copy of this book, in its English-language version.

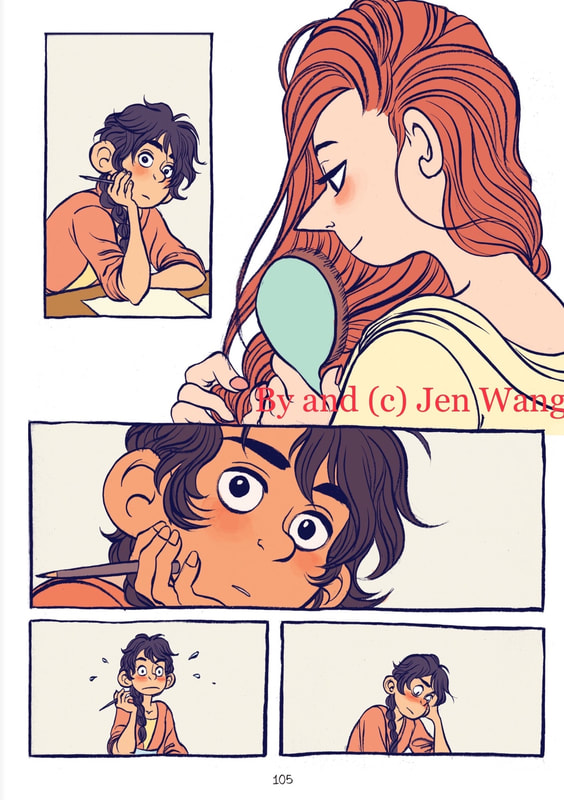

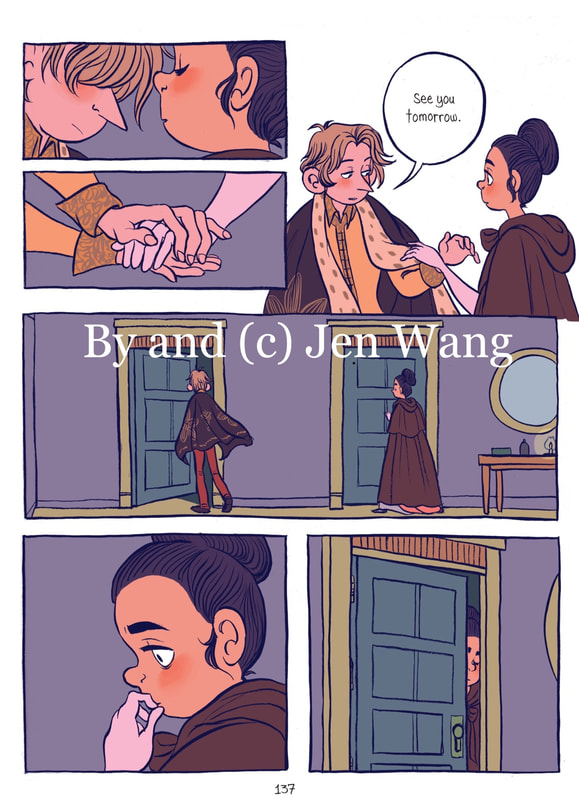

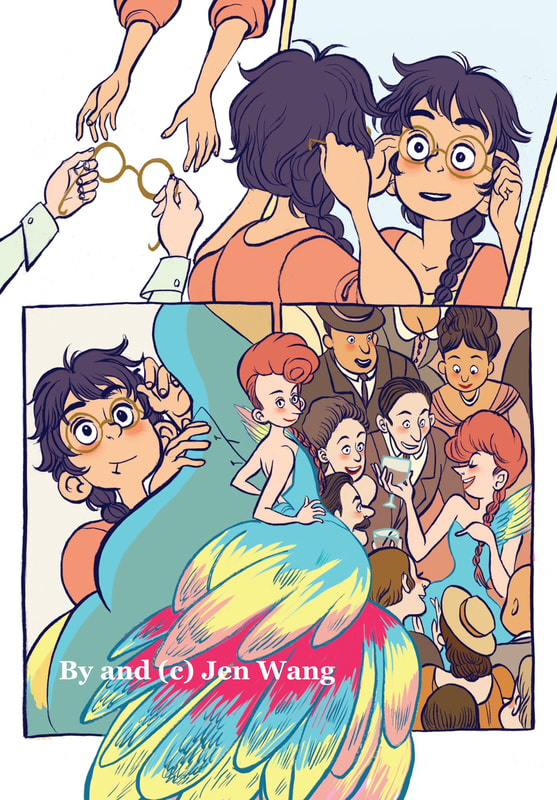

The Prince and the Dressmaker. By Jen Wang. First Second Books, February 2018. ISBN 978-1626723634. $16.99. (New to KinderComics? Check out our introductory post!) The Prince and the Dressmaker, Jen Wang’s new graphic novel, is her third, following Koko Be Good (2010) and In Real Life (2014). All her books have been well reviewed and admired, but this one is likely to be remembered as her breakout, deservedly so. A genderbending YA fairy tale romance set in a make-believe Paris on the cusp of modernity—a Belle Époque Paris with haute couture and department stores but no trace of Industrial Age grime—The Prince and the Dressmaker tells a tender story of nonconformity, the delicate art of public personhood, and desire. I especially like the way it does not editorialize about desire but instead evokes it, often wordlessly, hauntingly—without moralistic signposting and with a florid style that captures the flush of recognition and the confusion of feelings that desire can bring. A marvel of fluid, expressive cartooning, this book takes a fairly shopworn notion, that of the progressive fairy tale (often a go-to genre for feminist, gender-nonconforming subversiveness), and fills it with startling new life. It gives fresh evidence of Wang’s deftness and grace as a comics artist: her characters live, her rhythms draw this reader breathlessly in, and her pages pop. In short, this is artful work, fraught and emotionally daring, ultimately affirming, and, well, ravishing. As the above cover hints, The Prince and the Dressmaker is a prince-and-pauper fable about a process of artistic co-creation: the collaboration between a hard-working seamstress and designer, Frances, and a furtively cross-dressing prince, Sebastian, for whom Frances makes dresses. Sebastian endures his parents' attempts to marry him off to this or that young noblewoman but really only comes alive when he can venture into the world incognito, as Lady Crystallia: a fashion plate and the magnet of every elegant young lady's attention. It is Frances's skill and hard work that transform Prince into Lady; essentially, Crystallia is their joint work of art, with Frances as designer and Sebastian as model. Their clandestine partnership grants Sebastian a chance to live more freely, though only for brief, risky episodes, and Frances a chance to practice her art, but only anonymously. It's a match made in Heaven—or isn't, since each can only enjoy the work of creating Lady Crystallia by hiding or disavowing who they are. Sebastian remains closeted, and Frances remains unknown and unsung, denied the opportunity to take her skills public and fashion an autonomous career. The story tugs at this problem, and one other: that of unacknowledged, perhaps confused, desire. That is, The Prince and the Dressmaker is a love story as well as a Künstlerroman. The novel's plot is not especially devious or complex, and stakes out familiar territory. I'm reminded of feminist and queer-positive fairy tale books such as The Paper Bag Princess and King and King; feminist and queer-positive fairy tale comics like Castle Waiting, Princeless and Princess Princess Ever After; and the cross-dressing traditions of shojo manga (here slyly inverted) as well as manga's more recent explorations of transgender experience (notably, Shimura). Further, the faux-European setting, at once antique and yet salted with anachronisms in speech and manner, recalls the vague storybook Europe of Miyazaki. Familiar things, as I said. What Wang has accomplished here, though, does not boil down to a bald set of thematic or genre conventions; she wins on the details, which are myriad and lovely. The story comes across delicately, with expressive body language and telling grace notes of observation, and thankfully without intrusive narration or didactic underscoring. Frances and Sebastian have next to nothing in the way of backstory, but they remain distinct, visually quirky, well realized characters: Frances a mix of self-sufficiency, ambition, self-deprecation, and inquisitive desire (she looks at things very intently, yet sometimes bashfully looks away); Sebastian a dutiful, conflicted son as well as a lady (ostensibly genderfluid rather than trans), at times selfish or too caught up in his own need for safe hiding, at other times frank and courageous. Frances is willing to help Sebastian, and vice versa, because of mingled kindness, affection, and self-interest—and the willingness of each is tested. Both endure moments of terrible emotional exposure, betrayal, and bewilderment. Wang works the familiar turf beautifully. What I like best in The Prince and the Dressmaker is Wang's way with silence. Of the books 250-plus pages, almost a fifth are wholly wordless, and the great majority of spreads in the book include wordless panels or passages. The novel is entirely unnarrated, like a fast-moving film, but the delight Wang so clearly takes in rendering characters—and, my gosh, couture, in great, swooning, rapturous fits—roots the work in the pleasures of drawing and of comics. Some of the wordless passages dilate on brief sequences of action, catching and expanding small moments; others compress time, montage-style, whisking the characters through hours or days with giddy speed. The minimal wording and lavish drawing together convey ambiguous and conflicted emotion beautifully; witness pregnant moments of observation or reflection like this: The first example above seems, to me, to flirt with Frances's confusion about her own desires, or perhaps simply with the recognition of Sebastian's androgynous beauty. It says volumes. Both the first and second example show one of the things Wang is so very good at: emotional irresolution and the weight of the unspoken. Throughout the book, pairs of panels will hint at subtle interchanges and abashed feelings: All this happens against the backdrop of gorgeous pages, typically airy and free, generous with open space, against which panels and rows of panels appear to float. Bleeds are common: characters and scenes very often go right to the cut edge of the leaves (and implicitly beyond). Indeed Wang will often highlight a critical pause or loaded moment by placing a character at the bottom edge of the page so that the figure bleeds off, as if to hold the eye momentarily before the page turn. In any case, the pages are consistently dynamic without being attention-begging; Wang has a wonderful layout sense to complement her supple and expressive character drawings. No two pages are the same. I could go on about Wang's diverting artistry. It's the sort of thing I love to note: the kinetic freedom of her drawing; the exactness of the movements and expressions captured by her pencil and brush; the ravishing colors; the breath and pulse of the pages. But I think the things that really matter in The Prince and the Dressmaker are the narrative surprises and payoffs (er, these might qualify as spoilers, though I'll try to be vague): the cruelty of Sebastian's eventual exposure; the tender about-face that follows, upending cliched father-son dynamics; the delicious queering of a fashion show that serves as a sort of climax; and the final expression of the unexpressed that is, for me, the book's real climax. Of course all this is expertly cartooned, at the precise point where artistic discipline yields freedom. Yet it's Wang the total storyteller, the writer-artist, who finally gets to me. It's the complete package that made this jaded old reader daub his eyes. In sum, Wang has hit a new high. The Prince and the Dressmaker is very, very good comics, and puts the fairy tale tradition to wise ends. It envisions a better, braver world, one in which loving self-expression and artistic co-creation happily overleap ideological hurdles, setting more than one spirit free.

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed