|

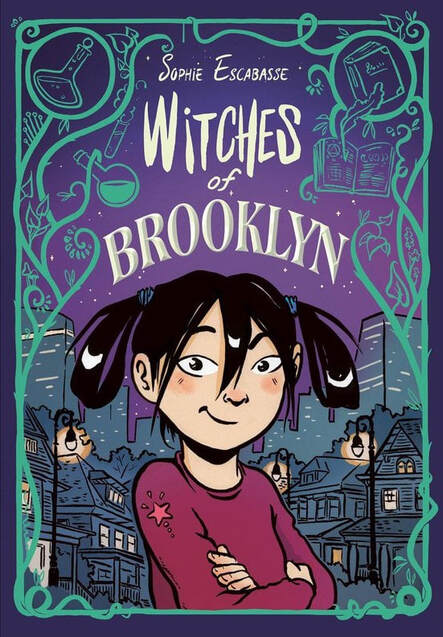

Witches of Brooklyn. By Sophie Escabasse. RH Graphic/Random House, 2020. ISBN 978-0593119273, $US12.99. 240 pages. In this middle-grade urban fantasy, the first in a planned trilogy, orphaned tween Effie is adopted by her eccentric aunts Selimene and Carlota, herbalists and acupuncturists who live in a quaint Victorian house in Flatbush. As it turns out, her aunts are also “miracle makers,” witches whose powers can bend reality and time—and Effie discovers that those powers run in the family. When a vaguely Taylor Swift-like pop star idolized by Effie runs afoul of some ancient magic and needs a cure, Selimene and Carlota take Effie into their confidence, and her training in magic begins. A clever, if rigged, story ensues, jammed with business, as Effie bonds with her aunts, makes friends at school, discovers the hazards of having power without knowledge, and becomes disillusioned with her former idol—but also saves her. The story abounds in Harry Potterisms and other well-worn tropes, and the frantic plot works against the bids for soulful characterization: for example, Effie begins as an embittered foster child with a chip on her shoulder, but then abruptly embraces living with her aunts, leaving all resentments and uncertainties aside. Hints of past unhappiness and family intrigue involving her late mother remain vague, perhaps foreshadowing sequels. There are plenty of loose ends. Author Sophie Escabasse’s style seesaws between joyous energy and fussy detailing. Her layouts are restless and dynamic, the traditional grids often enlivened by inset panels, frame breaks, and diagonals. There’s an enjoyable, exploratory quality about all this—the delight of seeing what a page can do—though the cluttered detail and overbusy coloring bog things down a bit. (On some pages, backgrounds are grayed out to bring the characters forward, which I think helps.) The characters are all distinct, with different silhouettes, head shapes, and faces—so different that they almost seem to have been drawn by different artists. Effie’s aunts are the most vividly realized and charming; in particular, Selimene, mercurial and feisty, stands out from the general busyness, with a comical design that recall Escabasse’s avowed influence André Franquin. Overall, Witches of Brooklyn strikes me as pretty good but also very familiar—so, I’m lukewarm toward it, despite its many good, smart moments. The sequels, I hope, will aim for less obvious plot-rigging, more rooted and consistent characterization, a sharper sense of what magic means and can do in this story-world, and, visually, not so much over-egging of the settings and details. As is, this first book crams in about three books’ worth of material and potential—I’d like to see Escabasse explore her world at a more deliberate pace. The second book reportedly will drop at the end of August.

0 Comments

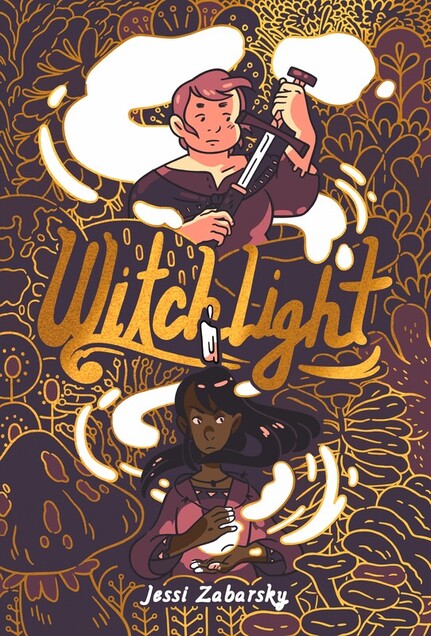

Witchlight. By Jessi Zabarsky. With coloring by Geov Chouteau. RH Graphic/Random House, 2020. ISBN 978-0593119990, $US16.99. 208 pages. I guess you say that this review is part of an occasional series (heh). In an unnamed land—a marvelous, culturally syncretic fantasy world—two young women undertake a magical quest and, as they go, learn how to care for one another. One of them, Lelek, volatile and enigmatic, is a witch who has lost half her soul. The other, her newfound friend (well, at first her kidnappee) Sanja, is determined to help find it. Love blooms between them—a matter of blushing shyness at first, but then owned and enjoyed with a winning matter-of-factness. As they travel, Lelek and Sanja scare up money by challenging local witches to duels, but often end up learning from those same witches; their travels uncover woman-centered communities and hints of matriarchal lore and magic. The larger culture hints at witch-hunting and misogyny, and this leads to a harrowing twist in the final act, but also, by roundabout means, to the resolution of a mystery and a ringing affirmation of Lelek, Sanja, and everyone they’ve befriended en route. Originally published by Kevin Czap’s micro-press Czap Books in 2016, Jessi Zabarsky’s Witchlight is a gorgeous and soulful feast of cartooning in a clear-line but vigorous, rounded style (which reminds me a bit of Czap’s own). It grows more confident in its linework and layouts as it goes. Beautifully colored by Geov Chouteau, the pages sing with an assured minimalism and harmony. I suppose the backstory and conflicts could be established more firmly—the plot might be clearer—but on the other hand, I enjoyed immediately diving back into the book to better understand its dreamlike premises. The book’s feminist, antiracist, and queer-positive ethos are a part of that dream and arise organically from the world Zabarsky has created; she uses her secondary world to imagine a better one. The utopian vibe is complicated by emotional and social nuances and an earned sense of loss and struggle. More than anything, Witchlight radiates a sense of love, offhand intimacy, and the thrills of self-discovery. Zabarsky clearly delights in her characters. She is a great cartoonist, with another graphic novel promised from RH Graphic by year’s end. I can't wait!

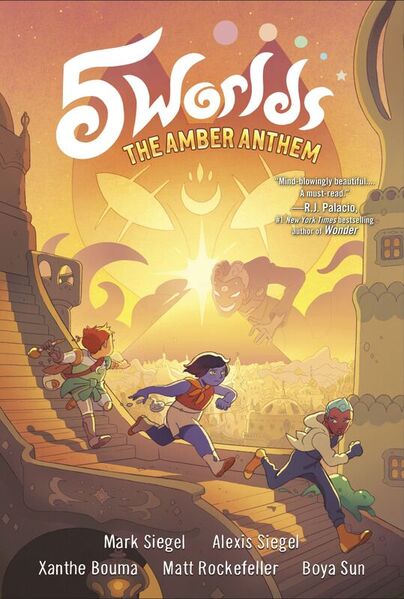

About eight weeks ago, I announced that KinderComics would be “taking a roughly six week-long break.” Every time I say something like that, I sigh—and sigh again when, eventually, tardily, KinderComics returns. So, okay, here I go again: Scheduling pressures under COVID, the endlessness of preparation and grading in my online teaching, and a looming sense that the world is going wrong, that it could explode any day—these things have been getting in my way. I admit I often consider closing this blog and moving on. Only reading and writing pleasure draws me back. So, let me switch gears and get down to the stuff that matters: 5 Worlds: The Red Maze. By Mark Siegel, Alexis Siegel, Xanthe Bouma, Matt Rockefeller, and Boya Sun. Random House, May 2020 Paperback: ISBN 978-0593120569, $12.99. Hardcover: ISBN 978-0593120552, $20.99. 240 pages. Who is the author of Five Worlds? This sprawling adventure series is the work of what seems to be an impossibly harmonious five-person team; somehow, the results comes across as the work of a single hand. Aesthetically, the series is gorgeous, a real feat of cartooning. Structurally, it’s tricky, with a modular, five-book shape, each book color-coded and focusing on a different world and different puzzle to solve (or secret to uncover, or McGuffin to find). Politically, it’s timely, with ever more obvious allegorical broadsides against Trumpism, neoliberalism, and xenophobia; in this progressive fantasy, world-building goes hand in hand with topical commentary that feels, as I’ve said before, on the nose. Alongside its familiar genre elements—the hype invokes Star Wars and Avatar: The Last Airbender as comparisons, but Miyazaki hovers over the whole thing too—Five Worlds conjures the anxieties of our times, and scores palpable hits against “fake news,” noxious right-wing media, climate change denial, and the shamelessness of greed-as-doctrine. KinderComics readers will know that I’ve been fairly obsessed with this series, reviewing Volumes One, Two, and Three in turn, and that I found the third, 2019’s The Red Maze, the most successful thus far at balancing genre convention, fresh discovery, and political relevance. With the latest volume, The Amber Anthem, the series has reached its fourth and penultimate act, and appears to be barreling toward a big finish. It’s actually a bit of a blur. In The Amber Anthem, the McGuffin is a song—the anthem of the title—and the story’s climax depends on thousands of voices lifted in song together, in a vision of peaceful yet powerful resistance that suggests real-world analogies: the Movement for Black Lives, and the recent surge in street protests despite COVID. (The book must have been written and drawn before that surge, and before the pandemic too, but its spirit of protest makes such analogies irresistible.) Here the dominant color is yellow, and the world is Salassandra, a planet briefly glimpsed before but now the center of the action. Our heroes, Oona, An Tzu, and Jax Amboy, once again seek to relight a long-quenched “beacon” in order to save the Five Worlds from heat death and environmental collapse. The Trumpian villain, Stan Moon—a host for the dreaded force known only as The Mimic—redoubles his attacks, even as Oona, An Tzu, and Jax take turns in the spotlight. The plot, as usual, is complicated, a tangled quest. Ordinary Salassandrans alternately help and hinder that quest (many having been persuaded that our heroes’ mission means ruin for the “economy,” and so on). The climax depends upon bringing together people of “five races.” Jax, a sports star, joined by a beloved pop singer, uses his celebrity to draw those people together—a handy metaphor for the way pop culture may provide opportunities for activism and community-building when official politics becomes hopelessly corrupt. Along the way, Anthem clears up several nagging mysteries, in particular the backstory of An Tzu (whose body has been, literally, fading away, book by book). I expected as much. Each new volume of Five World has delivered some big reveal or transformation for one of the heroes; now, with An Tzu’s history disclosed, the series seems poised for its finale. There’s a sense of unraveling complications here, yet of a tense windup at the same time. I confess that the big reveals here, though some of them came out of left field, didn’t leave me gaping or even happily stunned. Instead, I found myself jogging, not for the first time, to keep up with the frantic plot. Reveries and remembrances, sorties and missions, switchbacks and betrayals: it's a lot. The climax, though, is beatific: a shining vision of pluralism and collaboration and a lyrical evocation of “many strands…interweaving.” It's a triumphant close, but a corking good cliffhanger in the bargain, introducing a new moral dilemma and setting the stage what promises to be a breathless final volume. I’m keen—Five Worlds has been an annual stop for me, and I look forward to seeing how it all plays out. Five Worlds is a marvel of coordinated effort and cohesive design; again, its author-in-five-persons communicates like a single voice. Its world-building is lovely—I would happily pore through sketchbooks showing the collaborative process behind these books. That said, I’m starting to wonder whether the series’ complex rigging, breakneck plotting, and moral certainty are robbing it of some degree of complexity (as opposed to structural complicatedness, which it has in spades). The effect of Five Worlds on me, so far, has been like that of an action movie with soul, but its compression and momentum have not allowed for the sort of complex characterization that marks, say, Jeff Smith’s Bone, whose deepest characters, Rose Ben and Thorn, are sometimes at odds and go through hard changes. Five Worlds gestures toward the hard changes, and has enough soul to tend to the hearts and minds of its heroes, but everything feels a bit rushed. Despite the loveliness of the proceedings, then, at times the generic tropes come across as just that (Stan Moon, for example, speaks fluent Villain). When stories are ruthlessly streamlined, often what we remember are the clichés. I hope not. I look forward to the last chapter, The Emerald Gate, which I hope will bring everything—world-building, political urgency, and layered characterization—into balance one last, splendid time. When I open up the fifth and final volume, I’ll be holding my breath.

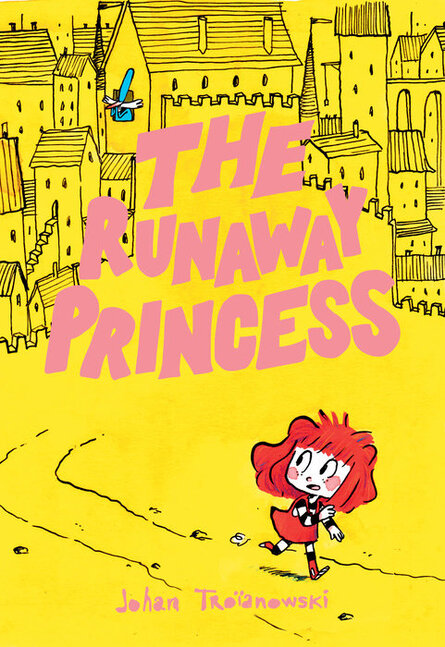

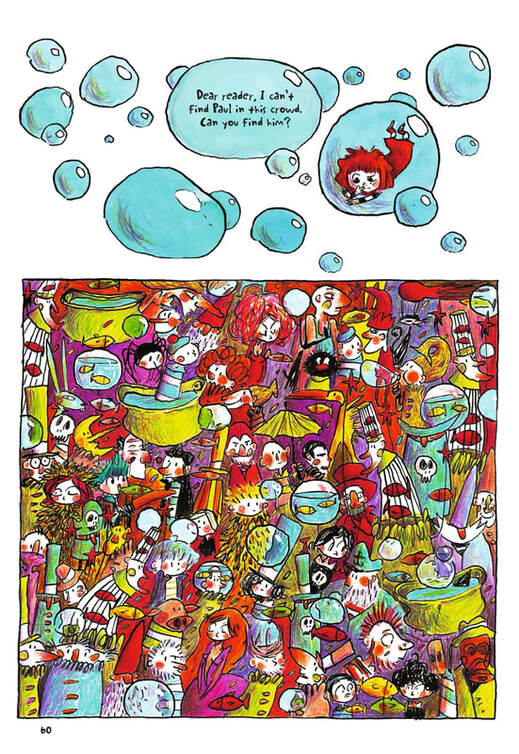

The Runaway Princess. By Johan Troianowski. Translated by Anne and Owen Smith; designed by Patrick Crotty. RH Graphic, ISBN 978-0593118405 (softcover), $12.99. 272 pages. January 2020. The Runaway Princess, a giddy, self-aware romp, celebrates doodling, play, and spontaneous worldbuilding. Its title and cover may suggest a feminist fractured fairy tale of the Princess Smartypants variety, but it’s really a Baron Munchhausen sort of yarn, a happy riot whose main lesson is pleasure. Not so much a deliberate novel as a spree, it showcases author Johan Troianowski’s freewheeling cartooning while riffing on familiar stuff. The first release under RH Graphic, Random House’s new comics imprint, The Runaway Princess translates Troianowski’s French series Rouge (2009-2017). The Rouge of the original becomes Robin here; she’s a wayward young adventuress with a touch of Little Red Riding Hood but also Pippi Longstocking. The world she travels is a vehicle for exuberant drawing and vivid, crayon-and-ink coloring. It’s also chockablock with drive-by homages to children’s literature, from classic fairy tales to Alice to The Wind and the Willows. Essentially, The Runaway Princess collects three rambling quests that consist of hide-and-seek, maze-walking, and casual discovery. In the first, Robin traverses a dark and threatening wood, where she befriends four lost kids, all boys, whom she leads out of the wood, to a strange city and festival. There some of the kids get lost again and have be found. In the second tale, Robin and the boys discover an underground world, where Robin befriends a witch, until the tale takes a darker, Hansel and Gretel-like turn; more hiding and chasing ensue. In the third, Robin and boys are cast away on an island, where a benevolent explorer introduces them to the culture of the Doodlers: small creatures who make art. Treasure-hungry pirates attack, and again the plot affords plenty of frantic running around. Notably, the book includes self-reflexive, interactive pages that invite the reader not just to read but to do things: solve mazes, shake the book, etc. That is, The Runaway Princess is a game of sorts; the book knows that it’s a book, and invites us to have fun with that fact. If Troianowski’s loose, scribbly style recalls Joann Sfar or Lewis Trondheim, his metatextual play recalls Fred’s classic Philemon series: as the plot bounces from one craziness to another, there’s little sense of danger or poignancy, more a benign, Fred-like absurdism and self-awareness. Troianowski excels at weird places—City of Water, Island of Doodlers—and favors graphic playfulness over tight logic, but it’s the direct appeals to the reader that make it work. Though The Runaway Princess would be at home alongside Philemon, or, say, Sfar’s Little Vampire, it lacks the philosophical weight of Fred and odd tenderness of Sfar, and sometimes reproduces Eurocentric, colonialist clichés (as in the ethnological Doodlers plot). Yet the book fizzes like a rocket, and cheerfully celebrates creativity (in this, it resembles, say, Liniers’s Written and Drawn by Henrietta). In sum, it’s is a breezy, inventive launchpoint for RH Graphic, and recommended.

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed