|

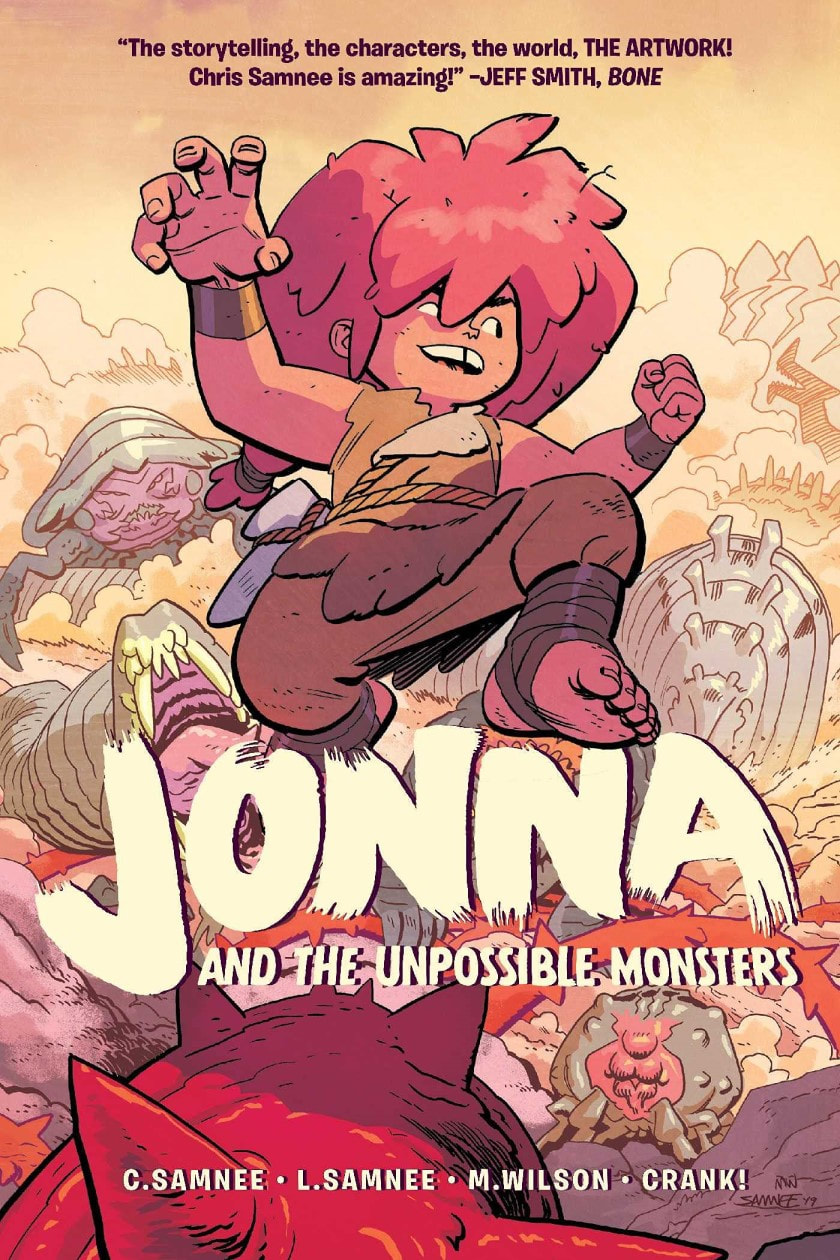

Jonna and the Unpossible Monsters. Book One. Written by Chris Samnee and Laura Samnee. Drawn by Chris Samnee. Colors by Matthew Wilson. Lettering by Crank! (Christopher Crank). Oni Press, August 2021. ISBN 978-1620107843, $US12.99. 112 pages. Jonna and the Unpossible Monsters has a premise that was just waiting to happen, one that somebody, somehow, had to get around to: a postapocalyptic children's fantasy about fighting giant, kaiju-like monsters. There's a touch of Jack Kirby's Kamandi, the Last Boy on Earth about this, and maybe a touch of Pacific Rim too. Co-creators Laura Samnee and Chris Samnee describe Jonna as a story they "could share with [their] three daughters," something created "for them" but also "inspired by them"; the comic, though, will appeal to action-starved fans of Chris Samnee's work on such superhero comics as Thor the Mighty Avenger, Daredevil, Black Widow and Captain America (or his current martial arts fantasy with writer Robert Kirkman, Fire Power). The heroic Jonna is a wild, monster-clobbering girl with a whiff of Ben Grimm or Hellboy. She comes across as untrammeled, almost feral, yet delightful. When Jonna goes missing in a ruined, kaiju-ravaged world, her older sister Rainbow – the more fretful, responsible one, naturally – tries to find her, then corral and (re)civilize her. Jonna, though, remains a unpredictable force of nature. You don't need to know much more; the first half dozen pages give you whopping big monsters, and plenty of synthetic worldbuilding. There's a sense of the familiar about all of it, but novelty and excitement too. By now it's almost a cliché to speak of Chris Samnee's masterful storytelling and sheer chops (I've paid tribute before). It is true that I will read just about anything drawn by him, especially when it's colored by Matt Wilson, his steady collaborator for more than a decade. Granted, I got impatient with Fire Power within a few issues. Though I dug its bang-up start, Fire Power strikes me as a shopworn White martial arts fantasy à la Iron Fist; it's tropey, and conceptually a bit tired. I've stayed with it, however, because of Samnee and Wilson's visuals, and it has become my monthly dose of old-school craft and loveliness, balancing breathless action with an Alex Toth-like elegance. Samnee manages to be polished and rugged at once; his drawing offers classicism and grace, but with a terrific infusion of energy. Jonna, I think, may be the best thing he has ever done: the pages sing, and roar, and astonish with their gusty action and playfulness. Freed somewhat from the stylized naturalism of mainstream superhero comics (though that skill set is still very much in evidence), Jonna cartoons with a joyful freedom. Wilson's coloring, too, is eye-wateringly good. All this is my way of saying that Jonna is craftalicious and affords plenty of gazing and rereading pleasure after the initial readerly sprint. But what does it amount to? On some level, it remains a kind of superhero comic, not only because Jonna packs a mean punch but also because a couple of other characters discovered along the way, Nomi and Gor, are seasoned fighters as well (Nomi boasts powerful prosthetic arms). So, this is a slugfest. But there's more: moments of poignancy, sisterly anxiety, and Jonna's weird, ferine energy and charming social cluelessness. And the Samnees allow a certain melancholy to creep in; the world of Jonna is a fallen one, full of sundered families, lost loved ones, bereavements. In one scene, a ragtag group of survivors huddles around a fire, and their dialogue says a lot: My whole family gone. My home destroyed. My village destroyed. Everything destroyed. Without pressing the point, the story has a genuinely apocalyptic feel that, to me, reeks of COVID. That it manages to be cockeyed and funny at the same time is no small feat. Though billed as a children's story, Jonna is just as much for grownups. The book (originally serialized in floppy form) splits the difference between direct market-oriented cliffhanger series and middle-grade graphic novel, so it's courting multiple audiences. Moreover, a theme of "families and belonging" (as the Samnees put it) threads through the book, familiar from many an animated family film, and like such films Jonna offers adults a kind of reassurance even as it aims for kids. That is, it offers childhood as a cure for ruin and heartbreak. The basic ingredients are familiar – there's nothing revolutionary about this tale – but I'm at a time in my life where seeing kids wallop monster does me a world of good. This first volume (a second is promised for Spring 2022) sets up some mysteries, not least the mystery of Jonna herself, and doesn't answer very many questions, but I enjoy paging through it and rereading it. In fact, I enjoy it more than I can say. PS. The excellent magazine PanelxPanel, by Hass Otsmane-Elhaou and company, devoted a good chunk of its May 2021 issue (No. 46) to Jonna, and includes a revealing interview with Chris Samnee. Plus, the issue contains other articles on depictions of children and on young readers' graphic novels. Well worth checking out!

0 Comments

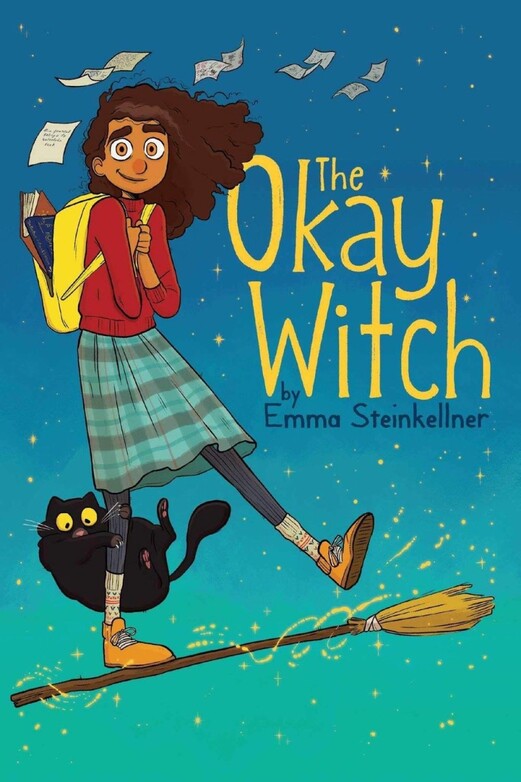

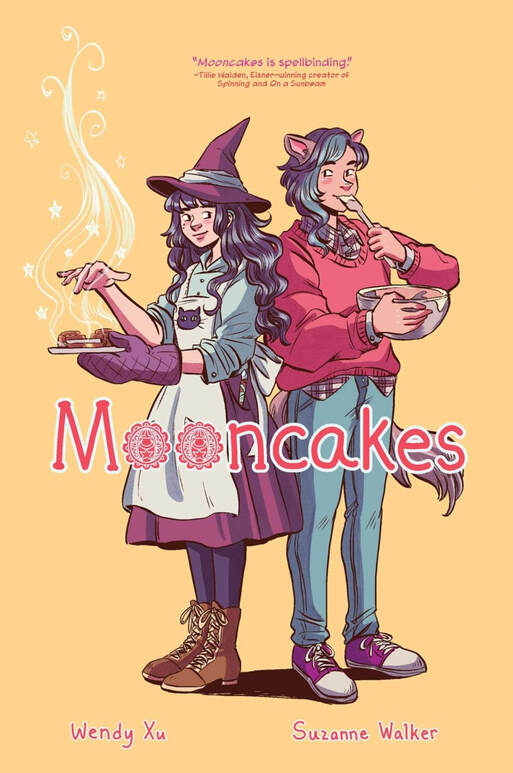

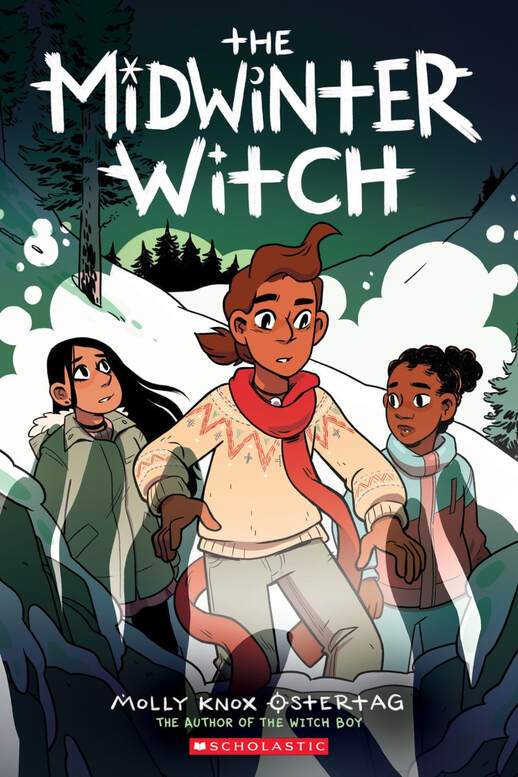

Coming-of-age stories about young witches have definitely become a genre in young readers’ graphic novels: a means of blending fantasy and Bildungsroman, and of telling stories about gender and sexuality, sometimes about other forms of difference, and about resistance versus conformism. Generally, these witch stories offer gender-conscious, often queer-positive, fables of identity. Post-Harry Potter, but often rejecting the Potter novels’ emphasis on passing in the mundane world, they also seem influenced by Hayao Miyazaki and the magical girl franchises of anime and manga. Here are reviews of three graphic novels about witches that came out, one after another, last fall: The Okay Witch. By Emma Steinkeller. Aladdin/Simon & Schuster, ISBN 978-1534431454 (softcover), Sept. 2019. 272 pages, $12.99. A girl named Moth, a misfit in her Salem-like town, discovers that she comes from a line of superhuman witches, her mother is more than three centuries old, and her family is entangled in the history of the town and its witch-hunters. Moth’s grandmother has retreated into a timeless, otherworldly utopia for witches, while her Mom has embraced the mortal world and sworn off witchcraft. Grandmother and Mom argue over Moth’s destiny, while Moth seeks her own way. There’s an intriguing story hook in this middle-grade fantasy, which poses an ethical dilemma about retreating from, versus engaging, an imperfect world — and suggests an allegory of America, in which women of color (Moth and family) expose and challenge the culture’s white-supremacist and patriarchal origins (the witch-hunters). However, The Okay Witch seems tentative and underthought, hobbled by blunt exposition, shallow characterization, and patchy drawing. Steinkellner’s characters are designedly cute and expressive (her style reminds me of Steenz), and she seems to grow into the work as she goes, but the results are unsteady. The breakdowns and staging of action sometimes confuse, the settings lack texture and depth, image and text do not always cooperate, and distractions such as crowded lettering and jumbled perspectives dilute the impact. The novel is progressive, hopeful, and charming, much more than the pastiche of Kiki’s Delivery Service suggested by its cover, but still strikes me as a derivative, uncertain effort. Mooncakes. By Wendy Xu and Suzanne Walker. Lettered by Joamette Gil; edited by Hazel Newlevant. Roar/Lion Forge, ISBN 978-1549303043 (softcover), Oct. 2019. 256 pages, $14.99. Mooncakes is a Young Adult fantasy about witches, werewolves, and demons, set in a world where magic is — well, not commonplace, but not unheard of either. More than that, it’s a gentle romance between two sometime childhood friends, now young adults: Nova, a witch who lives and works with her grandmothers (also witches); and Tam, a genderqueer werewolf and a refugee, running from cultists who seek to exploit their power. Even more, though, Mooncakes is a paean to community: a culturally diverse, queer one that helps Nova and Tam bind demons and face down their adversaries. The complicated plot hints at a world in which the relationships between technology and magic, humans and spirits, and the living and dead could take volumes to explore. Xu’s drawing is organic and expressive, her pages lively variations on the grid, with occasional dramatic breakouts. The settings are richly textured, the colors thick, a tad cloying. The emotional dynamics are enriched with grace notes of characterization (Xu and Walker know when to take their time). That Nova is hard of hearing is a point gracefully handled, neither central nor incidental. The story is finally a bit too pat, and reworks some shopworn elements — again, there’s that whiff of Miyazaki, with animal spirits and talk of a young witch’s apprenticeship. Yet the distinct characters and budding romance make it click. The Midwinter Witch. By Molly Knox Ostertag. Color by Ostertag and Maarta Laiho; designed by Ostertag and Phil Falco. Scholastic/Graphix, ISBN 978-1338540550 (softcover), Nov. 2019. 208 pages, $12.99. The Midwinter Witch rounds out Ostertag’s middle-grade Witch Boy trilogy — though I dearly wish this wasn’t the last book, since she has created such a beguiling world and winning family of characters. The series keeps getting better, and this volume hints at conflicts and potential that could sustain even deeper explorations. Here, Aster (the gender-nonconforming “witch boy”) and Ariel (a character introduced in the second book, The Hidden Witch) and their friends attend the Midwinter Festival, a yearly reunion of Asher’s extended family. There they compete in a tournament that requires each of them to face their fears: Aster’s of defying a strictly gendered tradition, Ariel’s of not fitting in, of being the orphan and odd witch out. Acerbic and defensive, Ariel is not sure she can become part of Asher’s very welcoming family. A dark force from her past looms up, luring her to a different path and leading to a confrontation that is all too quickly resolved — I wanted to know more about Ariel’s particular darkness and its source. The payoff, though, is lovely and affirming. The Midwinter Witch is a remarkably sure-handed work of cartooning, enlivened by deft, often silent, characterization, artfully designed pages that mix the grid with bleeds and multilayered spreads, and felicitous coloring. Overall, it’s a marvel of elegant, empathetic storytelling — a new high for Ostertag. By way of conclusion, I invite KinderComics readers with insights into this genre to weigh in with comments! I'd love to hear from readers with a strong interest in this kind of story; I'm eager to gain a fuller sense of the witch's tale, where it comes from, and what it might mean for culture and for comics. I see literary, cinematic, and anime/manga influences in this genre, but still find myself wondering, why is the witch's tale flourishing now, as a comics genre? How does the treatment of the witch's tale in comics differ from its treatment in prose?

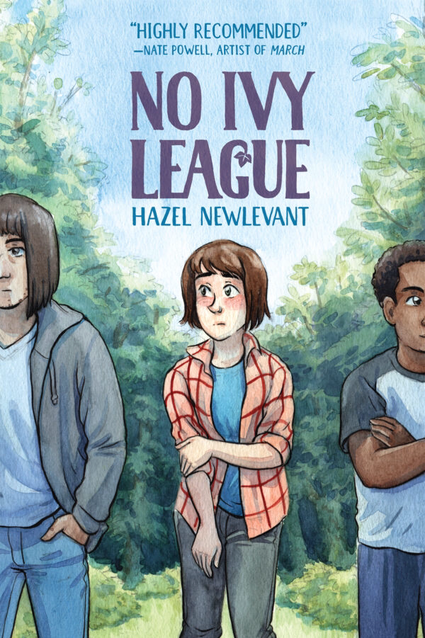

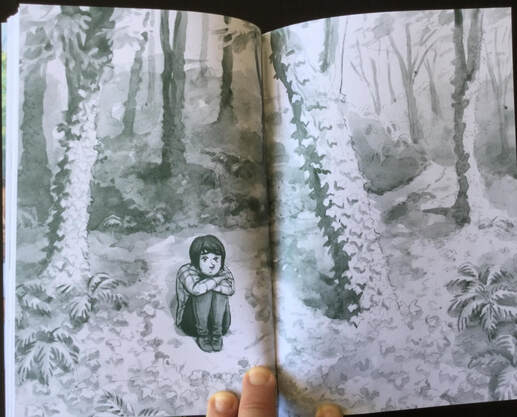

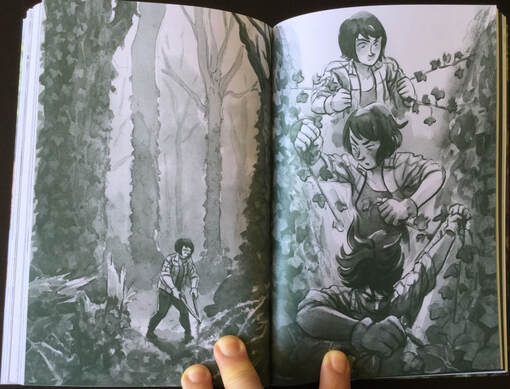

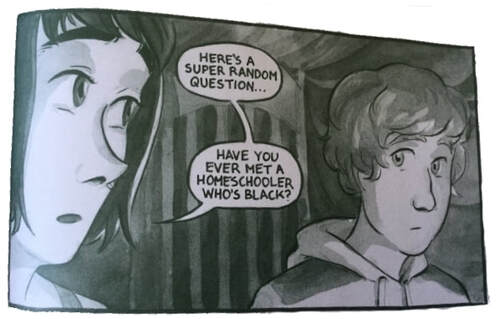

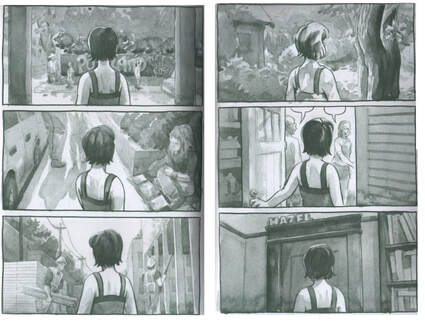

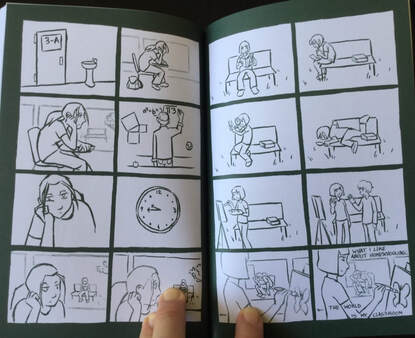

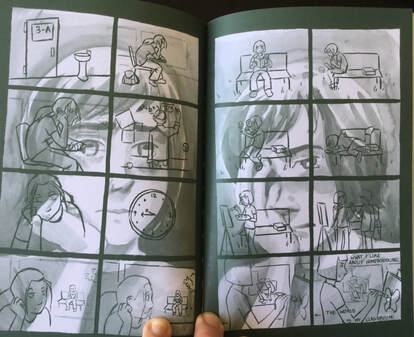

No Ivy League. By Hazel Newlevant. Roar/Lion Forge, 2019. ISBN 978-1549303050 (softcover), $14.99. 216 pages. No Ivy League, a memoir of adolescence, recounts a transformative summer in the life of author Hazel Newlevant. That summer, they (Hazel) took a first tentative step out of the cocoon of their homeschooled upbringing by joining a teenaged work crew clearing ivy from the trees of Portland, Oregon’s Forest Park. That crew consisted of high school students, diverse in class and ethnicity—a sharp contrast to Hazel’s sheltered, all-white life. (Note: I refer to Hazel the character by Newlevant’s gender pronouns they/them/their, though the book’s treatment of that issue is ambiguous: Hazel is addressed by her peers as “girl” or chica, but is seldom if ever referred to by pronoun.) Essentially, No Ivy League is the story of a challenging summer job. It depicts Hazel as not quite up to the challenge: a well-intentioned yet privileged and obtuse kid, painfully self-conscious, whose homeschooling has left them unprepared for the social and ethical challenges of getting along in a varied group. This can be inferred even from the book’s cover (above), which epitomizes Newlevant’s way of getting inside their teenage self and showing their social awkwardness and anxious aloneness. There are lots of fretful images of Hazel like this within the book. I’ve been looking forward to No Ivy League since Newlevant previewed the book at the 2018 Comics Studies Society conference (they were a keynote speaker there, in conversation with fellow artist Whit Taylor). It was a pleasure to meet them and hear them reflect on their creative process. Visually, the end result does not disappoint: the book boasts sharp, emotionally readable cartooning and atmospheric settings, built out of layered watercolor washes and selective touches of brush-inking (the book’s back matter demonstrates Newlevant’s process). The drawings are made of light and shade. Newlevant makes many smart aesthetic choices, not least the pages’ rich green palette, which, fittingly, often shades into deep forest hues. The overall look conjures the green spaces of Forest Park. This is a lovely, well-designed book. No Ivy League’s narrative, though, doesn’t quite convince me. It has a point to make; certain things (telegraphed in the jacket copy and in Newlevant’s own notes) are meant to come through clearly. Hazel is meant to see their own upbringing in a newly critical light, as they realize their white privilege and class privilege. In particular, they are meant to regret reporting a coworker of color for sexual harassment (one humiliating, profane remark), since their words cost that coworker his job. Guilt leads Hazel to examine critically the prevailing whiteness of home-school culture, and to research the history of integration busing in Oregon, which leads to a dismaying realization about their parents’ own motives for home-schooling them. In effect, all this teaches Hazel to recognize the privilege that separates them from their coworkers. But these revelations have a second-hand quality that doesn’t feel earned. This is not for want of trying on Newlevant’s part; individual scenes are nuanced, and Newlevant does not shy away from problems. But the book’s form, as a literal memoir, does not allow for a complex treatment of the diverse work crew in which Hazel finds themself. The storytelling remains too intimately tied to Hazel’s anxieties and desires, and never builds its other characters beyond hints. Those hints are good—they suggest what Newlevant could do with a freer novelistic development of the book's themes—but everything remains keyed to the growth of Hazel’s consciousness, so that, ironically, the book’s form ends up mirroring the self-absorption that Newlevant so clearly intends to criticize. The story’s resolution, which affirms community across ethnic and class lines, feels like a lunge for closure that isn’t warranted, based on what the story gives. In short, No Ivy League feels a bit signpost-y to me, i.e. forced. Still, there are terrific things in this book. For one thing, there’s a lot of smart dialogue and physical blocking. Newlevant well captures the awkwardness of Hazel’s social moves, their blundering, unsure way of making connections, and (again) their sense of isolation. For another, Newlevant does intriguing things with design, rhythm, and the braiding of details. A wordless two-page sequence captures Hazel’s alienation from their own once-comfortable surroundings: Hazel’s animated video extolling the advantages of homeschooling (their submission to a contest among home-school students) comes up twice, and the second time we see Hazel watching it with a more critical eye, their own expressions superimposed over the video’s images: On the other hand, the book includes some narrative feints that don’t come to much, such as a subplot about Hazel’s relationships with their boyfriend and with an older supervisor (on whom they have a crush). That narrative dogleg doesn’t seem to lead anywhere—though, to be fair, one could argue that that’s the point (perhaps Hazel puts aside romance in favor of a greater self-discovery?). To me, it felt like a dangling, untied thread. Overall, I was left feeling that Newlevant’s narrative reach had exceeded their grasp. Given a conclusion that feels willed but not organically attained, I came away with, mainly, a nagging desire to learn more about what I can only call the book’s “supporting cast” (an inadvertent testimony, perhaps, to Newlevant’s storytelling potential). No Ivy League, I think, wants a form better-suited to conveying its cocoon-busting message. That said, the book is visually elegant and transporting. Newlevant is a gifted cartoonist with a keen sense of place and mood. They are also, my criticisms aside, an ambitious writer who merits following. I urge my readers to seek out No Ivy League and give it their own considered reading.

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed