|

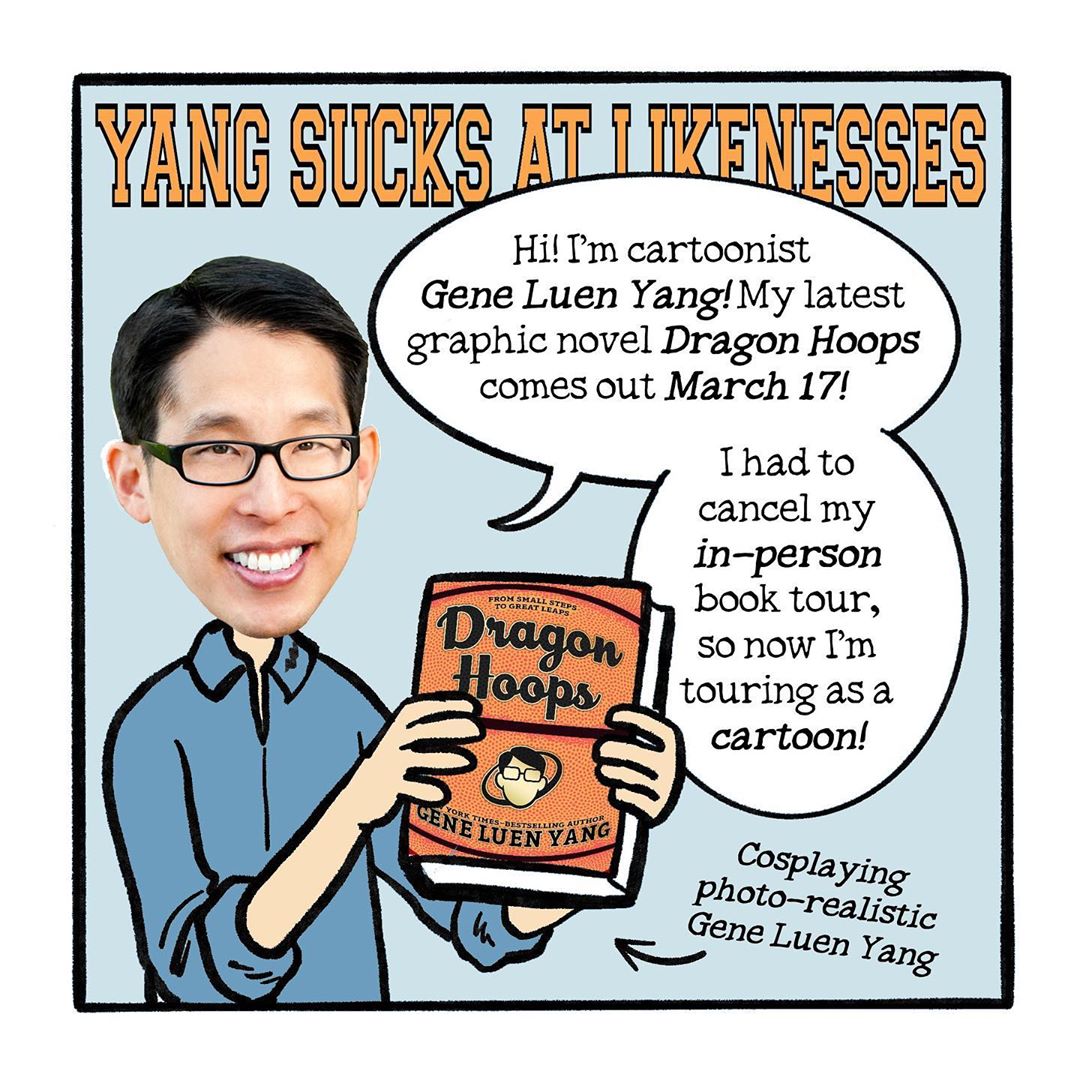

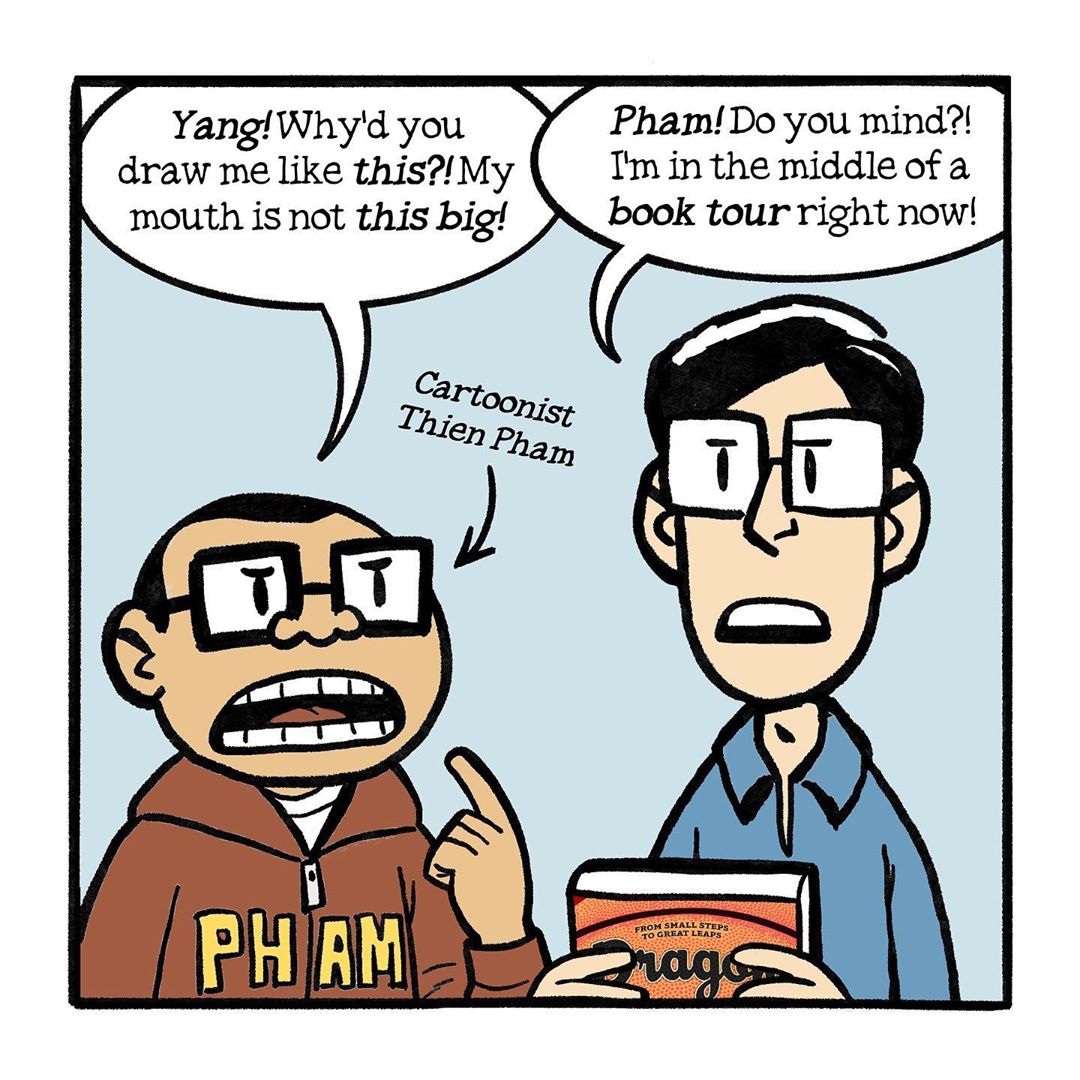

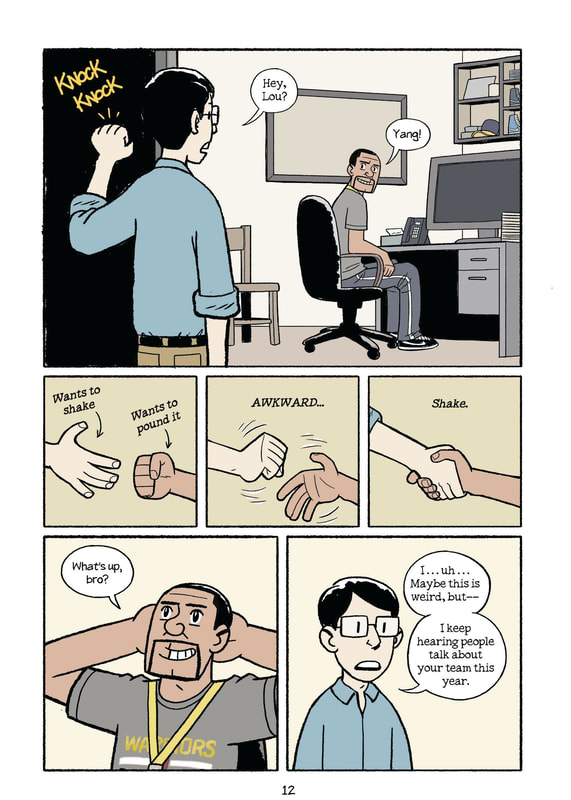

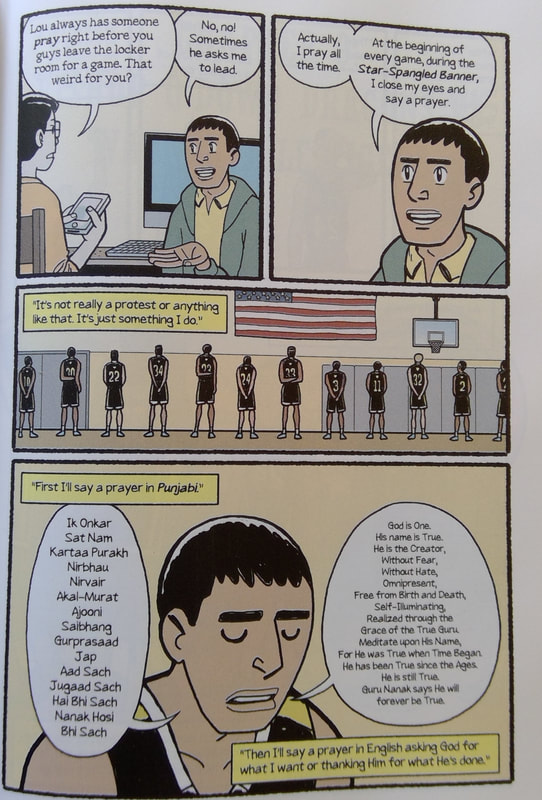

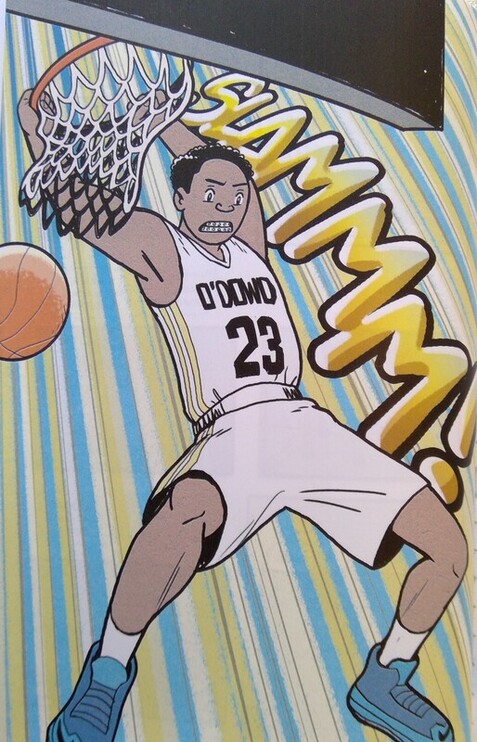

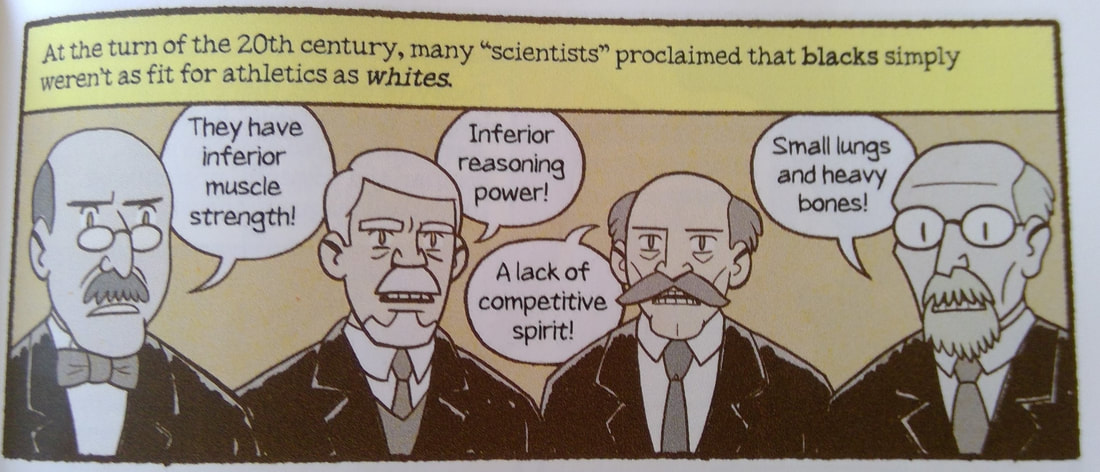

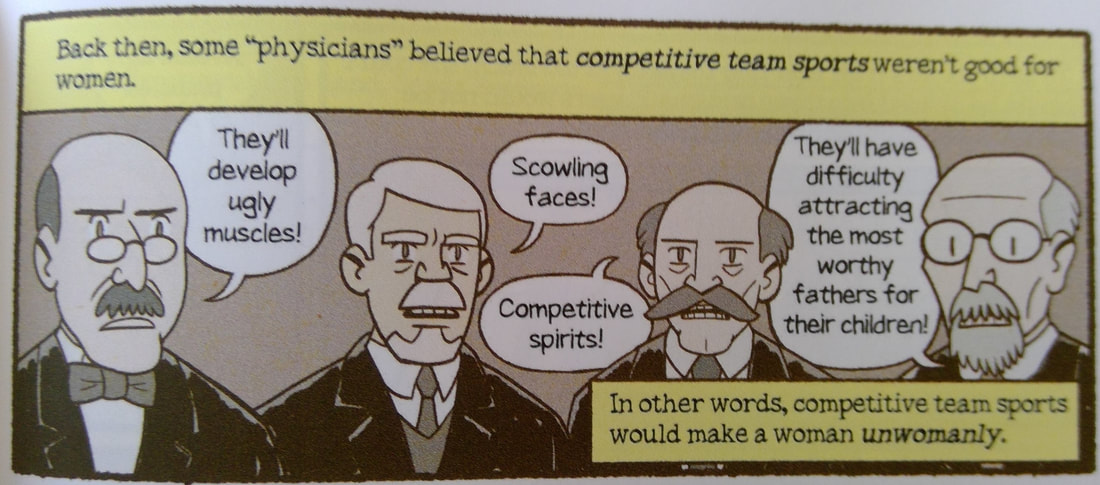

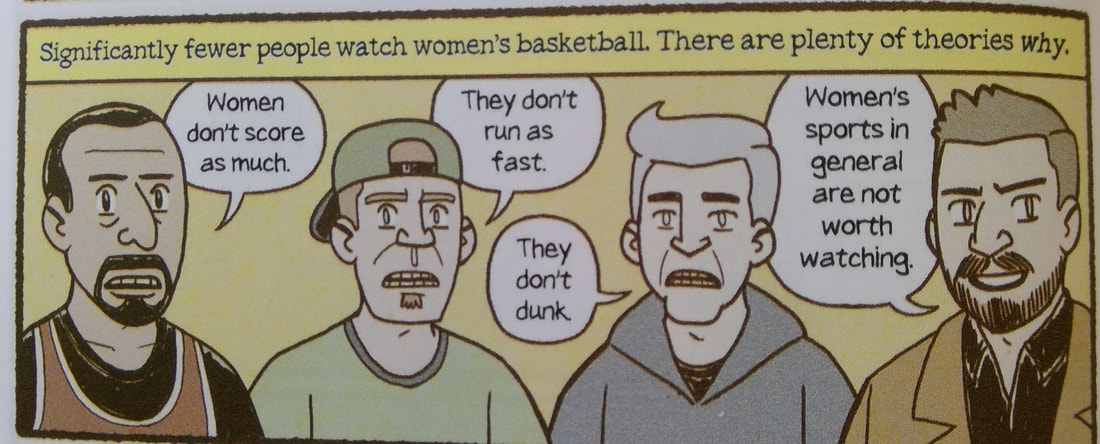

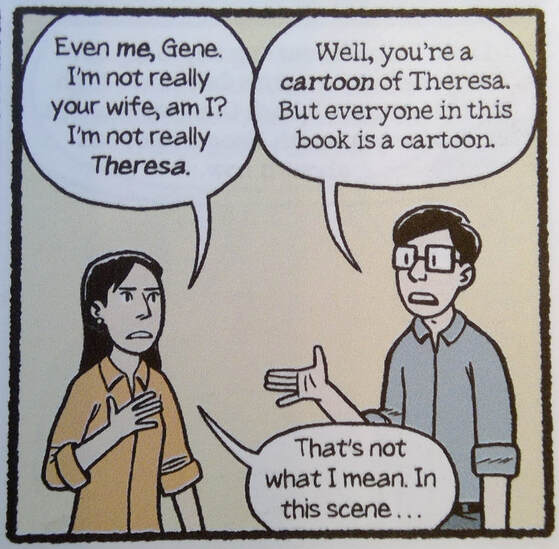

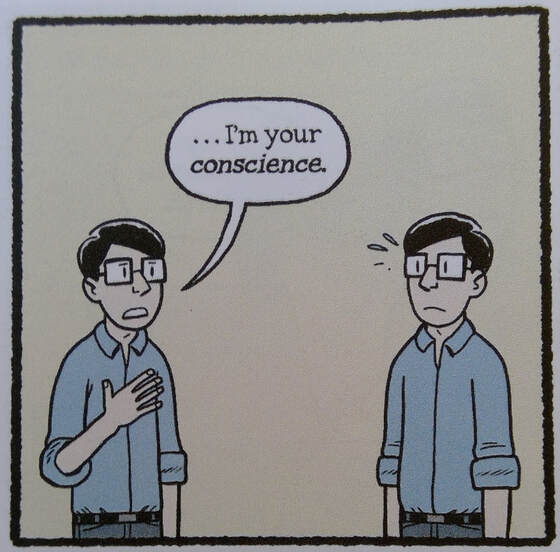

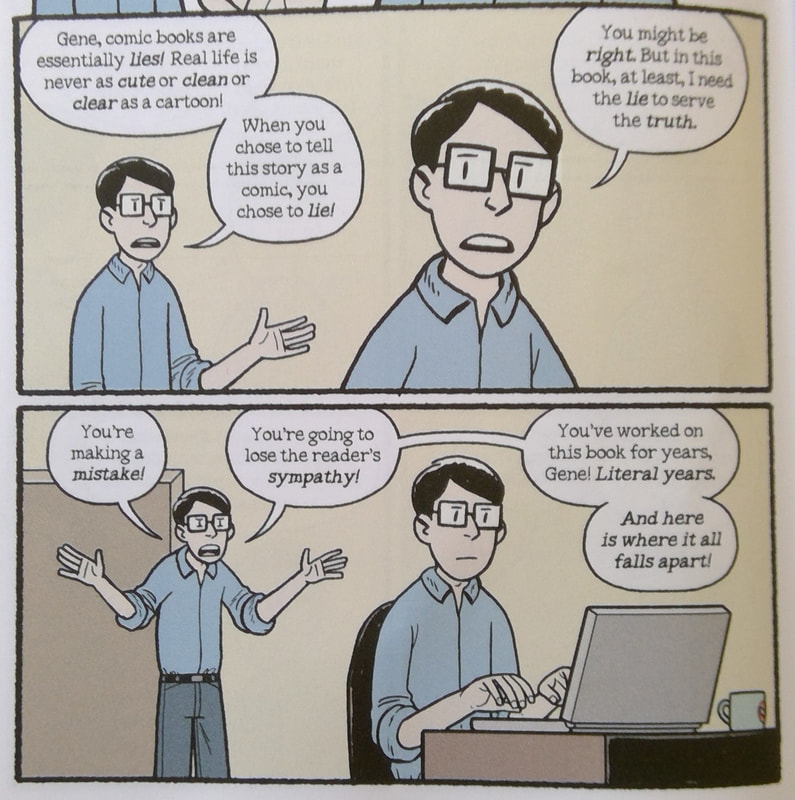

Dragon Hoops. By Gene Luen Yang. Color by Lark Pien. First Second. ISBN 978-1626720794 (hardcover), $24.99. 448 pages. March 2020. Recently Gene Yang has been out touring in support of his newest graphic novel, the just-released Dragon Hoops. But of course he hasn't been touring in the flesh; the COVID-19 pandemic has had him—like so many of us—holed up at home, trying to find creative new ways to engage with both his family and his public. Happily, he hit upon the idea of a virtual book tour: that is, promoting Dragon Hoops through a series of Instagram comic strips in which he responds to readers’ questions. These quick comics are formulaic, but the formulas are clever and engaging: Yang repeats shots and gags across the series, making it feel much like whistle stops before a loving audience that tends to ask the same few questions again and again. Of course, these comics are self-deprecating—more than anyone else, Yang is the object of his own jokes. He makes an excellent comic strip character. Humorous self-deprecation is one of Yang’s constants. He used to self-publish under the imprint Humble Comics, and if you’ve seen him speak you know that he excels at genial self-mockery. Yang plays humble the way Liszt played the piano—it’s his instrument. But don’t let him fool you: he is a gutsy and ambitious narrative artist whose work walks a tightrope between charming accessibility and willed difficulty. Yang takes chances. In particular, his solo graphic novels (as opposed to his many collaborative works) are fearsome high-wire performances. Dragon Hoops is no exception. Yang’s comics tend to be structurally tricky, thematically bold, and psychologically sharp. His breakout book, American Born Chinese (2006), semi-autobiographical yet fantastical at once, interweaves three stories in three different genres, until a startling moment that turns those three tales into one. The novel oscillates between ingratiating humor and terrible pain (in fact, those two tones are co-present throughout). Mixing myth fantasy, earthbound middle-grade school story, and arch sitcom, American Born Chinese is great comics, capitalizing on the form’s stable-unstable, multimodal heterogeneity to tell an immigrants’ son’s story, one of divided identity or fractured self. At bottom, it’s a story about internalized racism and self-hatred. A nervy book, it freely adapts China’s legendary Journey to the West, while at the same time insinuating a Christian allegory and riffing on Transformer/mecha pop culture. Moreover, it dares a form of grotesque satire, in which hateful, grossly racist anti-Chinese stereotypes reflect the protagonist’s self-loathing (a strategy as impious and risky as Art Spiegelman's notorious animal metaphor in Maus). In sum, American Born Chinese revealed Yang’s propensity for large-scale structural conceits that enact his own ambivalence and complex sense of identity. It was, is, daring. Yang’s follow-up project, Boxers & Saints, goes one better. A two-volume novel about China’s Boxer Rebellion, it’s a magic-realist historical fantasy in which the twin volumes represent, in a kind of tense counterpoint, both Chinese nationalist (Boxers) and Europeanized missionary (Saints) perspectives. Pitting the story of a young man who is an anti-colonial revolutionary against that of a young woman who is a Christian convert, Boxers & Saints balances Yang’s Catholicism against his pained awareness of Western imperialism and racism, while also critiquing strands of misogyny in traditional Chinese culture. The resulting two-headed novel, rather shockingly violent for Yang, represents a dramatic argument: a psychomachia in which different facets of Yang contend with each other, bitterly. Boxers completes Saints, and vice versa, and both volumes sting. This project shows, again, Yang’s penchant for teasing out self-conflict by counterposing different plots (in this case, different books!) and engineering complex structures. Identity in his books is as tricky as the plots: dynamic and never settled, an anxious balancing act. Yang's ingenious plotting, and an overall sense of high personal stakes, of storytelling wrung from pain, transform what could be flatly didactic into harrowing stuff. Dragon Hoops aims for this quality too, though it lacks the big structural conceits of the three-part American Born Chinese or two-part Boxers & Saints. It differs in another important way too: this time the tale is not historic, mythic, or crypto-autobiographical, but instead a literal memoir, an account of a year in Yang’s life as a teacher at Bishop O’Dowd High, a Catholic school in the Bay Area. Dragon Hoops is the longest overtly autobiographical work Yang has done. Yet it’s really about (huh?) basketball: on one level, Bishop O’Dowd’s varsity men’s basketball team, the Dragons, hungry for a state championship, but more broadly the entire history of the sport and how it intersects with race, class, and even Catholic schooling. In short, Dragon Hoops takes on basketball as a social force. This is something that the book’s version of Gene, archetypally geeky and sports-averse, has to struggle to understand. The story follows Gene from standoffish sideline observer (he is, at first, simply a storyteller looking for a new story) to ardent booster of the school’s basketball squad. At the same time, it charts a major shakeup in Yang’s own life, and offers multiple stories of struggle and vindication if not redemption. Further, it explores ethical issues involved in coaching, mentoring young people, and even Yang’s own storytelling. In fact, Yang worries on the page about what he is doing on the page. Here the book seems boldest--or perhaps most vulnerable? Dragon Hoops is long and complex (at about a hundred pages longer than Boxers, it is Yang’s heftiest single volume). Somewhere between intimate memoir, journalism, and oral history, it profiles the players on Bishop O’Dowd’s team, observes the complex social dynamics of their lives, and sets us up for, yes, a nail-biting climax on the court, at the longed-for championship game. Simultaneously, though, it recounts the creation and democratization, or broadening, of basketball, in a series of historical vignettes—while also depicting a transformative moment in Gene’s uncertain career in comics. That career comes to a sort of fortunate crisis when Gene, startled and uncertain, is offered a chance to write, of all things, Superman. Yang thus parallels the team’s story with a node of decision in his own life. In this way, the book explains why he is no longer at Bishop O’Dowd, and becomes a bittersweet valedictory to his seventeen-year stretch there (and perhaps a way of prolonging his connection to the school?). There’s a great deal happening in Dragon Hoops, then—the book’s seemingly straightforward structure conceals yet another gutsy high-wire act. This book is jammed full. Starting from a prologue in which Gene, reticent and awkward, seeks out Dragons coach Lou Richie, the story shuttles between present-day profiles and historical background, while also packing in loads of on-court basketball action. The team’s season, and Gene’s growing relationship with “Coach Lou,” are the spine of the book, but Yang freely intermixes other elements, with special attention to particular Dragons and how their team collectively embodies diversity. Chapters depicting important games alternate with chapters devoted to key players (in this sense, the book’s structure is very deliberate). Yang uses the players’ backstories both to celebrate basketball as an inclusive and egalitarian sport but also to point out various problems, notably racism and sexism, in the history and culture of the game. One chapter is devoted to a pair of siblings, Oderah, star of O’Dowd’s championship women’s basketball team, and her younger brother, Arinze, now part of the men’s varsity squad; the two are constant rivals, yet fiercely loyal to each other. Another chapter profiles Qianjun (“Alex”) Zhao, a Chinese exchange student on the Dragons’ team. Another focuses on Jeevin Sandhu, a Punjabi student of the Sikh faith—and here Yang focuses on the challenges of assimilation, while also providing, in effect, a brief introduction to Sikhism. There’s more. Dragon Hoops depicts James Naismith, who invented basketball in 1891; Marques Haynes and his fellow Harlem Globetrotters, who helped integrate the game; Senda Berenson, who launched women’s basketball; Yao Ming, the first star of Chinese basketball to thrive in the NBA; and other notables in the game’s history. Yang smartly interweaves present and past: the chapter on Jeevin also recounts the rise of Catholic schooling and the career of early NBA star George Mikan, a Croatian American player from a Catholic seminary; Yang then acknowledges that Jeevin, as a Sikh, is an outlier in Bishop O’Dowd’s Catholic culture (a scene of Jeevin reciting the Mul Mantar, a Sikh prayer, complements other scenes of praying in the book). Similarly, the chapter on Oderah and Arinzes weaves in Berenson’s story and the rise of the women’s game, including a historic dunk by pioneering college player Georgeann Wells. You can feel Yang matching up elements from past and present to build a tight, cohesive book. Visually, Dragon Hoops is likewise purposeful and designing. Breathless scenes of action on the court, sometimes parsed down to the split second, recall the sort of intense basketball manga popularized by Takehiko Inoue (Slam Dunk, Buzzer Beater, Real). These scenes attain an energy and forcefulness that exceed Yang’s previous work (even the martial violence of Boxers & Saints). There are sequences that fairly set my pulse racing. What makes these explosions of action thrilling is the way the book as a whole carefully measures out its storytelling, and uses the very controlled braiding of repeated imagery to reinforce its themes. Yang recycles and repurposes the same signal images over and over, to point up thematic parallels between past and present, among the different players, and between the Dragons’ quest for the championship and his own concern about going “all in on comics” as a career. Dragon Hoops is a library of key images, reworked and re-inflected (indeed, it could take the place of the vaunted Watchmen when it comes to classroom lessons about braiding!). In fact, it’s a brilliant sustained feat of cartooning for the graphic novel form; the book echoes back and forth, as Yang plays the long game. There’s a kind of nervousness, though, behind Yang’s cleverness. Dragon Hoops is an anxious, self-conscious work. Like Spiegelman’s Maus—and a great many other graphic memoirs since—it reveals and worries over its own stratagems. The authorial notes in the book’s back matter frankly discuss Yang’s sourcing and his occasional resort to artistic license. Said notes relate to the main story dialectically and at times critically (reminding me of the disarming notes in several books by Chester Brown). In particular, Yang admits that he has cast his wife Theresa as, essentially, his sounding board and proverbial better half: wise and practical, humorously tolerant of his anxieties, and full of advice and encouragement (or reasonable doubts about his judgment, as the occasion demands). Talking to Theresa becomes a means of registering Gene’s doubts about his own project, and the sometimes choppy ethical waters that the project gets him into. Though Theresa makes an impression, she does not really emerge as a full-blown character (and the same could be said of Theresa and Gene’s children). Yang notes that he took “particular liberty” with her dialogue: “I figured I could because, y’know, we’re married.” His notes are full of revealing asides like these, which invite a closer look at Dragon Hoops as a performance and a made thing, not just an artless recording of real-life events. Yang’s self-reflexive disclosure of his artistic feints happens not only in the back matter but also in the main story. Dig these two successive panels, on either side of a page turn: In particular, Yang depicts himself worrying over a single compromising plot point: a deeply troubling element of real life that threatens his desired “feel-good” story but that he feels he cannot omit. That ethical sore point is seeded about a third of the way into the book, after which Gene frets and frets over it—until a moment about four-fifths in, when Gene, or rather the book, enacts its moment of decision: Readers of Maus may be reminded of Art’s insistence that “reality is too complex for comics"—which Yang echoes here, stating that comics are “essentially lies.” (Spiegelman too sometimes casts his wife, Françoise Mouly, as a sounding board whose dialogue makes his work’s ethical complications clearer.) In the case of Dragon Hoops, this sort of self-reflexive gambit becomes a fundamental plot element, in fact a suspense generator, long before Yang reveals precisely why. We spend a good part of the book wondering what he is hiding, and how he will reveal it (of course, this plot tease makes it obvious that at some point he will). This isn’t a terribly original move—graphic memoirs have been depicting the rigors of their own making since at least Justin Green—but here it feels almost like a forced move, as if Yang was compelled to it by unnerving real-world details that he could not wish away. Anxiety over this point fundamentally shapes the book’s narrative structure. Dragon Hoops, then, perhaps seeks to inoculate itself against criticism. That is, Yang’s self-critical gambits (there are many) may be meant to deflect charges that his expert storytelling massages the truth a bit too much. I’m not sure that such charges would be fair—but I confess I don’t think Dragon Hoops is Yang’s most convincing graphic novel. Whereas American Born Chinese and Boxers & Saints continue to hint at mixed feelings even as they aim for conclusiveness and wholeness, this book wants to feel emphatically resolved. Yang’s trademark ambivalence yields to a sort of boosterism. At times, Dragon Hoops seems to apply the “underdog” template of most sports stories rather uncritically; for example, the book registers some complicated thoughts about sports, coaching, and Catholic education that its final pages don’t so much resolve as hush. Me, I would have liked to see more critical engagement of what it means to turn young athletes into media stars. I would have liked to see more of Coach Lou’s self-questioning. Dragon Hoops is smart and honest enough to acknowledge problems in the culture of sports, but still wants us to cheer at the final buzzer. Maybe it’s an ironic tribute to Yang’s storytelling that, in the end, I wasn’t quite there. In any case, the book’s reigning structural parallel—how the courage and tenacity of the Dragons empowers Yang to go “all in” himself, as an artist—feels a bit rigged alongside the terrible dilemmas depicted in his previous novels. But, man, it's hard to begrudge Yang the effort, because so much good stuff happens along the way. Dragon Hoops captures a culture, community, and season vividly, and is the very definition of what we should want from a major artist: a step in a new direction, and a dare-to-self that plays out in complex ways. No one could accuse Yang of making things easy on himself. And the book has taught me a lot. As my wife Mich and I take our daily break from isolation, walking the quiet neighborhoods around us, waving (distantly) at passers-by, we see a lot of basketball hoops on driveways and in yards. In fact, a couple of days ago, as we walked uphill through another neighborhood, we heard the sounds of shooting hoops before we came upon the sight: a quick dribble, a silence, a thudding backboard, then more of the same. Sure enough: someone was practicing basketball, solo, in a rear driveway, just barely visible above a tall gate. I had this book on my mind, and had to smile.

0 Comments

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed