|

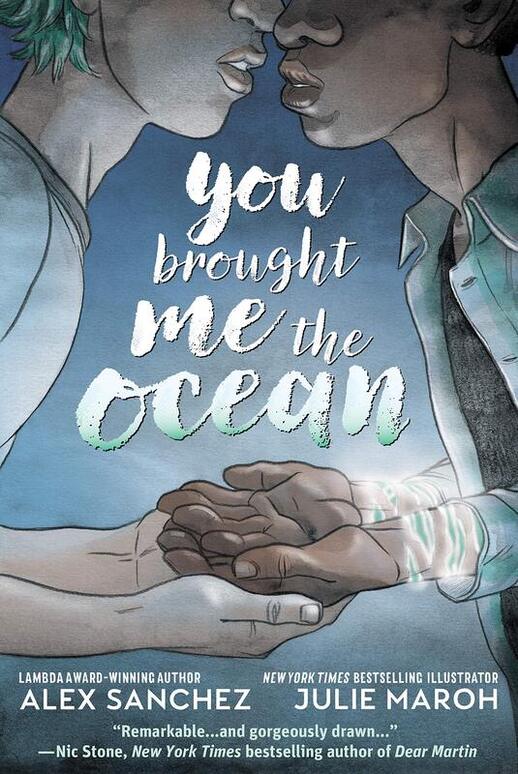

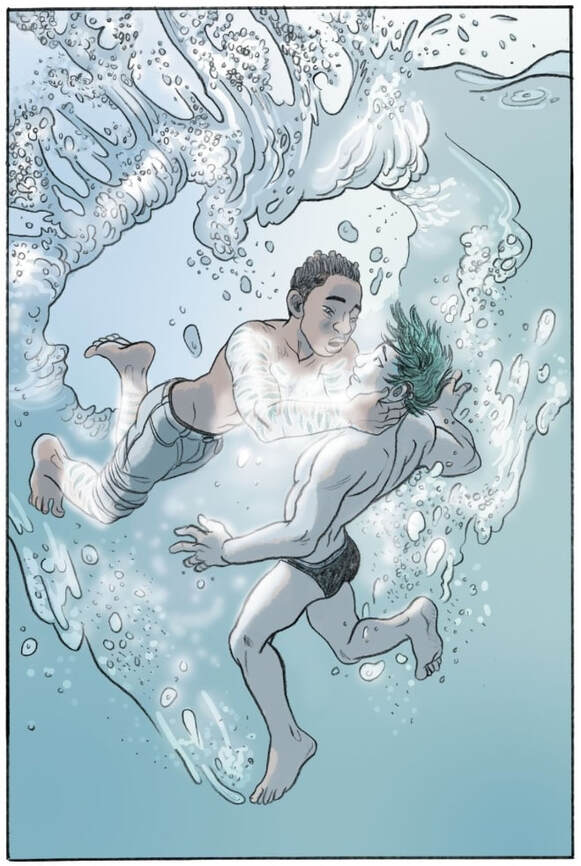

I have not been a fan of 21st-century DC Comics. Often I have criticized DC for not acting like a real publisher and for pushing more of the same ugly, self-defeating work: grim heroes, continuity porn, line-wide reboots, and other rigged and desperate moves. But nonetheless I found myself reeling from this week’s news of massive layoffs and restructuring at DC, part of a general purge at WarnerMedia (Heidi MacDonald has the best think piece on this that I’ve seen, over at The Beat). That was hard news. With DC losing a reported one-fifth of its editorial staff—indeed, as MacDonald says, “almost an entire level of editorial executives“—and the company’s publishing plans downsized, this seems like a fraught moment for comic-book culture here in the USA. I have to imagine that it’s a heartbreaking moment for many; the human cost of this sweep is considerable. It’s hard to know what to expect of DC going forward, though. Can we perhaps read some silver lining into this storm cloud? Interestingly, DC editorial will be run by two women (for the first time ever?), Marie Javins and Michelle Wells, the latter the head of DC’s Young Reader division. And, as MacDonald speculates, it seems likely that “DC’s kids and YA books will be more important going forward.” I take that as good news—but I’m afraid the news for direct-market comic book shops doesn’t sound so good (see my recent reflection on that subject here). DC Publisher Jim Lee, who remains in place after the layoffs, gave an interview to The Hollywood Reporter last Friday that puts a bright face on the changes; it seems intended to be reassuring. But I’m not reassured. (See Heidi MacDonald and Rob Salkowitz for informed readings of that interview.) I am, however, guardedly impressed by DC’s current Young Adult line, despite initial skepticism and misgivings about the work continuing to be work-for-hire in the traditional DC way. This brings me to (forgive me for pivoting so sharply) a happy review of a newish book: You Brought Me the Ocean. By Alex Sanchez and Julie Maroh. Lettered by Deron Bennett. Edited by Sara Miller. DC Comics, ISBN 978-1401290818 (softcover), 2020. US$16.99. 208 pages. (BTW, this is the third in an occasional series reviewing children’s and Young Adult graphic novels from DC. See the first here and the second here.) You Brought Me the Ocean is a smart, beautifully rendered queer YA romance in the guise of a superhero origin story, and a whole, rounded novel to boot. Despite being set in a desert town, it’s about water, about the ocean, and about learning to live as an “amphibian” in a mostly dry world. There’s something about Aquaman in it, and Superman does a distant fly-by, but, really, this story belongs to young Jake Hyde, his lifelong friend and neighbor Maria Mendez, and the young swimmer Jake falls in love with, Kenny Liu. (Jake is basically a new take on the Young Justice version of Aqualad, for those keeping track.) Kenny opens new doors in Jake’s life, just as Jake has to contemplate leaving home for college and a complex shift in his relationship with Maria. Fittingly named, Jake Hyde is closeted in several ways—in fact he is an unknown even to himself—but the story represents his coming out and coming into his own, folding together hero-origin tropes with high school and romance conventions. Loved ones and bullies alike exhibit homophobia—but, with the exception of one foul thug, the major characters all reveal unexpected depths and changeability. Characters disappoint, but then happily surprise. As Jake realizes his powers—the reason for the strange, scar-like markings on his skin—he, Maria, and Kenny become a triad of friends, and the denouement is wish-fulfilling but not pat. (There could and should be a sequel.) If Ocean revisits some familiar stuff—protective or disapproving parents, homophobic bullies repping toxic white masculinity—its characters are distinct and nuanced, and have humanizing touches. Further, the familiar stuff feels pretty convincing: these aren’t cliches so much as things that commonly happen and should be acknowledged. The book has a confident sense of its characters from the first; I can believe, for example, that Maria and Jake are longtime friends, with a shared history and personal language. Their interaction feels real enough. Scriptwriter Alex Sanchez (Lambda Award-winning author of the Rainbow Boys trilogy) handles characters and world deftly, with a smart, unforced touch. And artist Julie Maroh (Blue Is the Warmest Color) seems to know these characters’ physicality—their carriage and body language—as well as an artist could. Maroh’s figures are compact, sensual, and expressive. Most importantly, they are distinct. You Brought Me the Ocean benefits from a unified aesthetic that is unusual for DC Comics. Bathed in watery blue and silver-gray, and then again in muted desert browns and tans, the book enacts the major conflict in Jake’s life through its very palette. Thanks to Maroh and designer Amie Brockway-Metcalf, it boasts a visual wholeness and integrity that set it apart. Subtle yet dynamic layouts, unhurried pacing, and mostly understated action define the book, which sidesteps epic superhero dust-ups in favor of smaller, though still dramatic, discoveries. That said, the art remains ravishing; Maroh’s individualized figures and muted colors cast a spell even as they do the vital work of characterization. This appears to have been a harmonious, lovingly edited collaboration; it’s a remarkable feat for a first-time team. As I said, I’d read more. You Brought Me the Ocean is YA superheroics done with grace and a sensuous visual language. In fact, it’s only a superhero story on its edges; fluency in the DC Universe is not required. At heart, it’s an affirming story of love and friendship with a fantastical, magic-realist touch. Recommended! PS. KinderComics is taking a roughly six week-long break, sigh, so that I can start the new semester at CSU Northridge more or less sanely. See you in about a month and a half!

1 Comment

This is a dreadful, harrowing time in my country, and such a harrowing, wonderful time in comics. It's a rich and confounding, confusing and delightful time, promise-crammed despite the body blows that comics retailers, publishers, creators, and readers have had to endure and continue to endure. At this moment of real change in the American comics business, I am reminded that I founded KinderComics precisely to learn new ways of looking at comics and to challenge my own tastes and habits. That experience keeps on going, more dizzying and eye-opening with each passing month — and, speaking selfishly, that's a continuing gift to me. As a comics scholar and critic, I'm blessed to have an "object of study" that just won't sit still. Please forgive a bit of navel-gazing: KinderComics covers children's and young adult comics from a perhaps unusual angle: I'm a comics fan weaned on (first) newsstand and (then) direct-market comic books, a reader of superhero comic books for nearly fifty years who wavers between nostalgia for and impatience with that genre, and, on the other hand, an adherent of alternative and art comics in the post-underground tradition. At the same time, academically, I'm a scholar-teacher of children's literature and culture. These different experiences and commitments sometimes come into conflict, hopefully in a stimulating, useful way for my readers. I come at young readers' graphic novels with great enthusiasm but also a dose of, I hope, healthy skepticism regarding how they are promoted and judged. This skepticism has been stoked by both my knowledge of the long history of comics and the academic study of childhood as a cultural construct. More than anything, though, I'm just interested in good comics, no matter what audience or bloc they are marketed toward. As I say on this blog's About page, I'm strongly invested in the idea of comics as a form of art and of text with its own traditions and aesthetics, and...I'm less concerned about work that is "good for" or improving for children, more concerned about work that I find artistically startling and enriching. In other words, I have an abiding interest in comics' aesthetic form that tends to outweigh even considerations about what works for children and adolescents as readers. And I tend to look at contemporary comics for young readers against a long backdrop of historic comics for and about children, including comic strips and comics magazines; that is, I resist the presentism of the graphic novel era. Further, I resist questions framed in terms of "age-appropriateness" or didactic agenda. As a teacher of children's literature, I often have to field such questions — for example, what age is this book for? — but I tend to fence with such questions rather than answer them outright. A bad habit, maybe — probably a frustrating habit for my students! — but that's me. I'm interested in young reader's comics as an aesthetic revolution, not just a social and educational one. That, for me, is what KinderComics is all about: following a new source of good comics. With all that in mind, I'm keenly interested in news about the shifting markets for comic books and graphic novels in the US, especially the news that sales in my beloved direct market (that is, the network of comic book specialty shops) are being overtaken by comics sales in the mainstream book trade — plus the news that kid-oriented original graphic novels are surpassing superhero and related comic book serials in sales. Now, these are not very surprising bits of news; in fact, I founded KinderComics with the expectation that this would happen, that it was only a matter of time before the stats reflected these changes. Lately, the stats have been dramatic: if comics sales enjoyed something of a record year in 2019, it was books aimed at young readers that drove that sales spike. Here are a few recent sources that confirm these trends:

One concern of mine — a concern further stoked by the pandemic emergency — is that direct-market comics shops are in a poor position to compete with mainstream bookstores and online retailers when it comes to selling original graphic novels. This is not because comic shops lack expertise or good customer service; in fact, many comic shops do a good job of hand-selling comics graciously, with a personal touch, because they tend to know their customers. But comic shops within the direct-market system do not enjoy the advantages of returnability and deep discounts that an entity like Amazon takes for granted. Structurally, they simply have a hard time competing with high-volume retailers that can afford to sell some books at a loss in return for customer loyalty and bigger returns down the road. As the balance of sales shifts from traditional DM floppy or pamphlet comics to original graphic novels, the decks are somewhat stacked against comic shops. Bookstores, Amazon, and the Scholastic book fairs (Scholastic is by far the number one comics publisher in the US right now) work by different rules. What were advantages when dealing with a fan clientele in the direct market have become liabilities as comics shift their footing to different retail channels. The huge upsurge of comics in children's and YA publishing has everything to do with this sea change. Even before COVID-19, the challenges of returnability and working with multiple distributors were insuperable barriers to many direct-market comic shops. Rolling with the changes is not easy. The commercial dominance of original graphic novels for young readers requires new arrangements and new thinking, lest comic shops be shut out of comics' most explosive growth spurt in generations. I'm watching in the shadows of COVID, anxiously, hoping that my favorite comic shops — the kind that combine expertise and passion, carry and promote most genres, and work hard to serve a diverse community of readers — can survive and find the means to adjust to a potentially bright, yet differently structured, future. Beyond outlasting this pandemic, I think adapting to the rise of young reader's graphic novels is the greatest challenge facing North American comic shops today. This is not simply because comic shops tend to be more welcoming environments for adults than for young readers (some shops have already sought to create a more welcoming atmosphere). It's also because the terms of the business make it hard for comic shops to compete for original graphic novel readers. Negotiating new terms and risking new forms of outreach will have to be part of the comic shop toolkit, going forward. As I said, a rich and confounding, confusing and delightful time. I think I created KinderComics as a way of thinking through this time. Thanks, readers, for joining me.

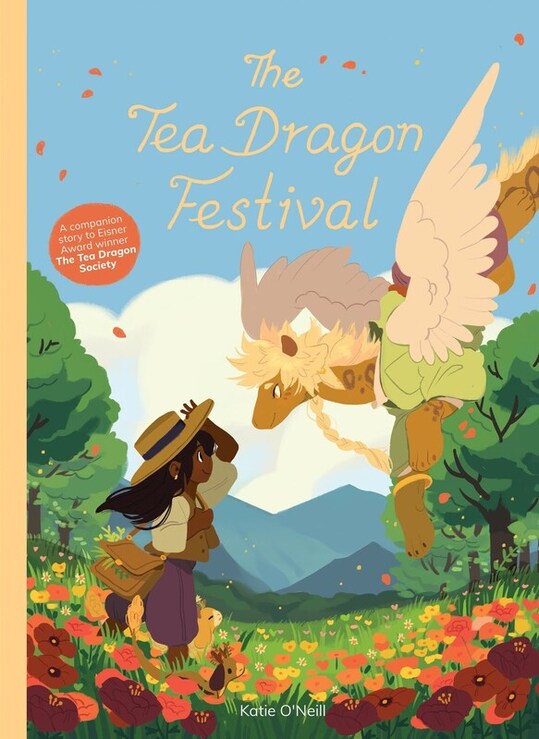

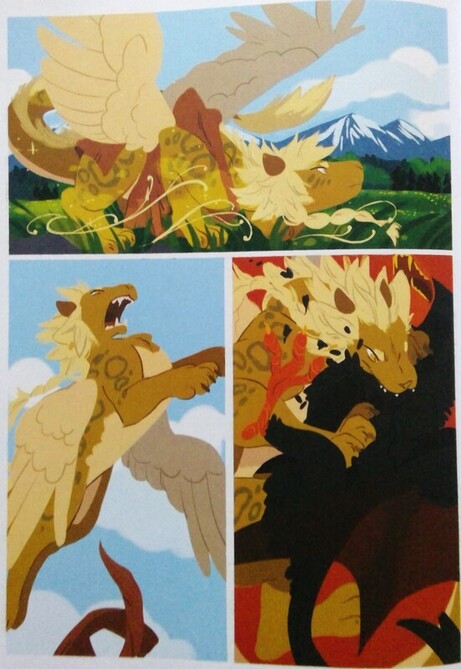

The Tea Dragon Festival. By Katie O’Neill. Oni Press, ISBN 978-1620106556 (hardcover), 2019. US$21.99. 136 pages. I read The Tea Dragon Festival during an early morning idyll, propped up in bed with a cat curled up on my lap (our cat Max likes to hang with us when we read). That sounds about right — it’s that kind of book: tranquil, comforting. A purring cat, basking in a morning ritual, is a pretty good stand-in for the semi-domesticated “tea dragons” that populate its world. In fact, here on KinderComics I described this book’s predecessor, The Tea Dragon Society (2017), as an “idyll full of greenness and life” and a “cat-lover’s daydream.” The same goes this time. The biggest problem I had with this sumptuous book was reading it by diffuse sunlight: O’Neill’s occasional layering of dark or muted colors posed a challenge to my eyes; I couldn’t make out certain expressions and overlapping shapes. I ended up having to turn on my reading lamp and point it directly at the pages — then the expressions popped. So, I recommend reading The Tea Dragon Festival by strong light; then you’ll really get to see O’Neill’s ravishing color work. When well-lit, the book fairly glows. Cover blurbs describe Festival as warm, charming, and gentle. Again, that sounds right. The story skirts pain and hardship; though it evokes some subtle melancholy, its characters are not burdened with difficult ethical decisions or hard losses. The vibe is green, dreamlike, and utopian (with the now-expected traces of Miyazaki). The one potential source of serious conflict appears and disappears in a handful of pages. In fact, the book is so quiet and anodyne that it’s quite a surprise when a fight briefly breaks out: Like its predecessor, Festival takes place in an eco-topia: an idealized rural culture defined by caring community and respect for traditional crafts. The story, again, focuses on a growing girl who is learning a craft — in this case, cooking — and her interactions with dragons — this time, not just miniature tea dragons but also a full-blown, shape-shifting, often humanoid dragon. This dragon, Aedhan, considers himself the appointed protector of the girl, Rinn’s, village, but has been waylaid by a magical, eighty-year sleep, from which he has only just awoken. He is filled with regret for the years he has missed. Rinn takes responsibility for helping Aedhan get to know her people and acculturate to village life — so, once again, the story revolves around the sharing of memories, as Aedhan moves from outsider to trusted villager. Though longer and more ambitious than the first book, then, Festival takes up the same concerns and exhibits the same qualities. I like O’Neill’s work for emphasizing, as I’ve said before, loving connection and tender gestures. But I have to repeat another observation too: this book’s delicacy left me wanting more complication, more trouble. I wanted a harder story, something that would show the characters’ values when put to a fiercer test. It’s easy to love the world O’Neill has created, one of sharing and openness, indeed a queer, feminist, anti-capitalist utopia. Clearly, she herself loves the world and its characters. I particularly like the inclusion of signing (American Sign Language) as a plot element, which sharpens O’Neill’s already impressive sense of (in this case literal) body language. The story, though, gives no sense that the apple cart has ever been upset, or the people’s equanimity challenged, by the ordinary work of survival. O’Neill seems to prefer quieter dilemmas, smaller stakes. Festival is sweet and affirming, but its plot evanesces soon after reading, leaving behind an impression of a personal wonderland, exquisitely tended and mostly about the pleasure of its own rendering. I’ll happily read more by O’Neill: she’s a gifted cartoonist and book artist. Each time I read her, though, I become terribly aware of my own cynicism. Harrumph!

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed