|

My posts to KinderComics usually focus on the pleasure of reading, and usually contain at least one image. The following post does neither. I trust my reasons will be clear: Over roughly the past two weeks, the US comic book and graphic novel community has been roiled by revelations of sexual harassment, abuse, and predation committed by prominent and admired creators (see here, here, and here for starters). Implicit in the coverage of these outrages is the understanding that habits and presumptions in the field at large have to change, that too much of the field has been complicit in covering up or downplaying, or simply nodding toward and tolerating, these outrages for too long. Even known instances of harassment and abuse, as in the case of Scott Allie at Dark Horse, were let slide, or palmed off with inadequate in-house reprisals that don’t seem to have changed anything. Comics in the US is dealing, belatedly, with the same injustices that have marked other cultural fields, including children’s publishing (recall the sexual harassment crisis of 2018: see here, here, and here). This is not the first #MeToo moment that the US comic book field has had, but it may be the loudest, most impactful, and most propitious of those moments — one that, I hope, will spark not only short-term outrage and equally short-term promises of change, but real, sustained, systemic change: to editorial and personnel practices, mentoring and networking practices, comic-con culture, and the things that all of us stakeholders in comics say (or fail to say) to one another. Quick bursts of performative outrage won’t matter in the long run; what will matter is recognition of the field’s general complicity in these matters, and taking practical steps to propel the field out of complacent gear-lock and into active attention, to alert status. This will be a matter of more than pledges; it will have to be a practical matter of who gets hired, whose voices will get amplified and believed, whose words will reverberate in the proverbial room where it happens, and what comicdom’s gathering spaces do to set policy and expectations. Fan spaces such as cons have been pushing for stronger anti-harrassment policies and new etiquettes and safeguards (see for example here, here, and here); professional spaces both inside and outside of cons must do the same. I have no special wisdom when it comes to addressing these issues. In fact, I’m troubled by my own record of bland complicity in the unthinking sexism of our society — and of comics culture. Despite recoiling from the more obviously sexist and misogynistic content of many comics, I’ve often been blinded by complacency. I will have to work proactively to expand the scope of my empathy and recognize the scope of what I just don’t know. What I do know is that I’m a participant in this culture and share in its problems, and that concrete, deliberate policies will mean more than vague affirmations. A proactive commitment to anti-sexism is needed, and that’s an ongoing thing, not just a matter of signing a pledge. Of special concern to KinderComics is the news out of the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, a long-lived nonprofit that works to protect freedom of expression in the comics field. The CBLDF, I believe, has a crucial mission — but its reputation has been damaged, its future jeopardized, by its failure to address sexist, and sexual, wrongdoing within its own organization. This week, longtime executive director Charles Brownstein has resigned under pressure, due to renewed and intense public outcry over his sexual assault of a comics creator at a convention in 2005 (and other charges that have come to light once more). The convention incident became known in 2006, thanks in part to investigative journalism by Michael Dean of The Comics Journal. The CBLDF, however, kept Brownstein on, despite damning coverage. Though the Fund reportedly took punitive and rehabilitative measures with Brownstein, the shadow cast by his misconduct has dogged the organization. This past couple of weeks, the Fund drew severe criticism on social media, Twitter particularly, with prominent industry voices pledging to withdraw or withhold support from the Fund unless Brownstein were removed (and, some added, the CBLDF board took steps toward serious internal reform). Brownstein’s resignation was reported by the CBLDF on Monday, June 22. This was long overdue — and now the Fund is being called to answer publicly for its years of supporting Brownstein. Again, I believe that the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund does essential work on behalf of comics creators, publishers, retailers, librarians, educators, and readers. Formed in 1986, incorporated in 1990, the Fund “provides legal referrals, representation, advice, assistance and education to cases affecting the First Amendment right to read, create, publish, sell, and distribute comics and graphic novels.” More simply (I’m quoting the CBLDF website here), the Fund “help[s] individuals and businesses who are being criminally prosecuted because of the comic books they read, make, buy, or sell.” Further, it “help[s] libraries gather resources to defend graphic novel challenges.” This is a mission that matters to me greatly — and I believe it matters to the future of comics for young readers. Some organization needs to carry on that mission. As children’s and young adult graphic novels have become a staple in libraries across the US, comics have repeatedly appeared on the lists of “most challenged” books, and the kinds of cases the CBLDF has worked on have changed, as has the Fund’s promotional literature. Much of the CBLDF’s outreach these days goes beyond the diehard comic book hobbyists who were its main public at first, and the Fund now organizes convention panels and produces resources aimed at librarians, teachers, and parents. CBLDF staff have sought to promote inclusivity, spotlighting women, queer, and trans creators of comics, celebrating anti-racist comics, and putting on progressive convention events. They have, most definitely, defended young people’s right to read freely. So it’s disconcerting to hear stakeholders in the comics community declare the organization obsolete or hopelessly rearguard or corrupt. Yet the CBLDF brought this on itself — which is why the voices of its severest critics should be heard, regarded, and discussed. We’re going to need a new model CBLDF, or a new organization that does the same sort of work. The injustices in the Fund’s own history, though, cannot be ignored. The challenge here is to get beyond regretful mea culpas and into the active position of doing something substantial. I believe there needs to be a public accounting by the CBLDF board, and revision of its charter to address issues of sexual harassment in comics culture and within its own ranks. I hope the organization will exhibit the will and courage to address this problem — a great deal depends on what they do next (the most recent statements from the Fund give me some hope). I also believe that a legal empowerment fund, comparable to that once attempted by the now-defunct nonprofit Friends of Lulu, is desperately needed for women, and for queer, trans, nonbinary, racialized, and disabled persons, working in the comics field. If the CBLDF can’t or won’t participate in civil suits, then another mechanism is needed to help support the victims of harassment, stalking, manipulation, exclusion, and bigotry in our community. These are alarming times, for so many reasons — but, again, they are also propitious times. Things can be done, concretely, spiritedly, vocally, forcefully. I hope they will — but of course hope has to be an active, doing thing, not a matter of waiting for the ship to right itself.

0 Comments

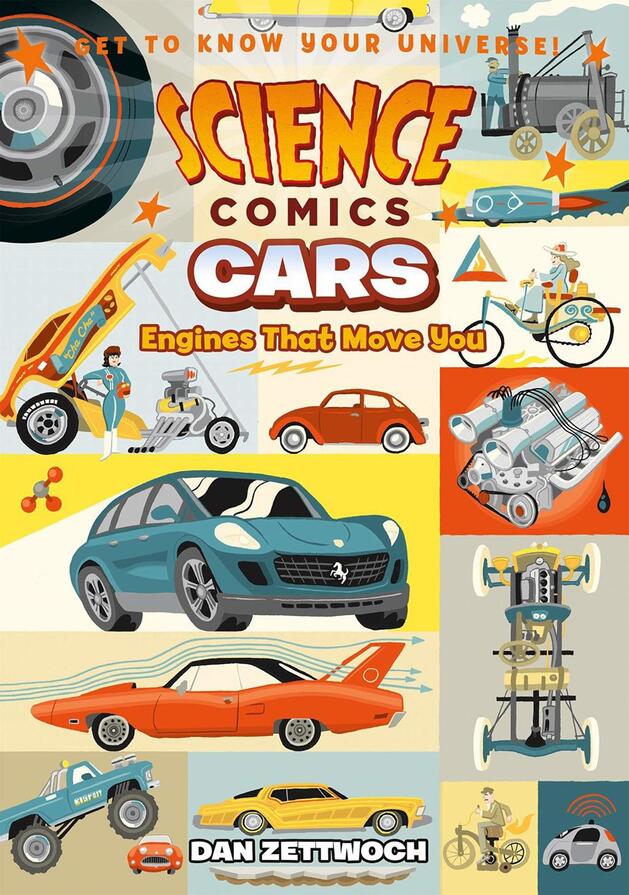

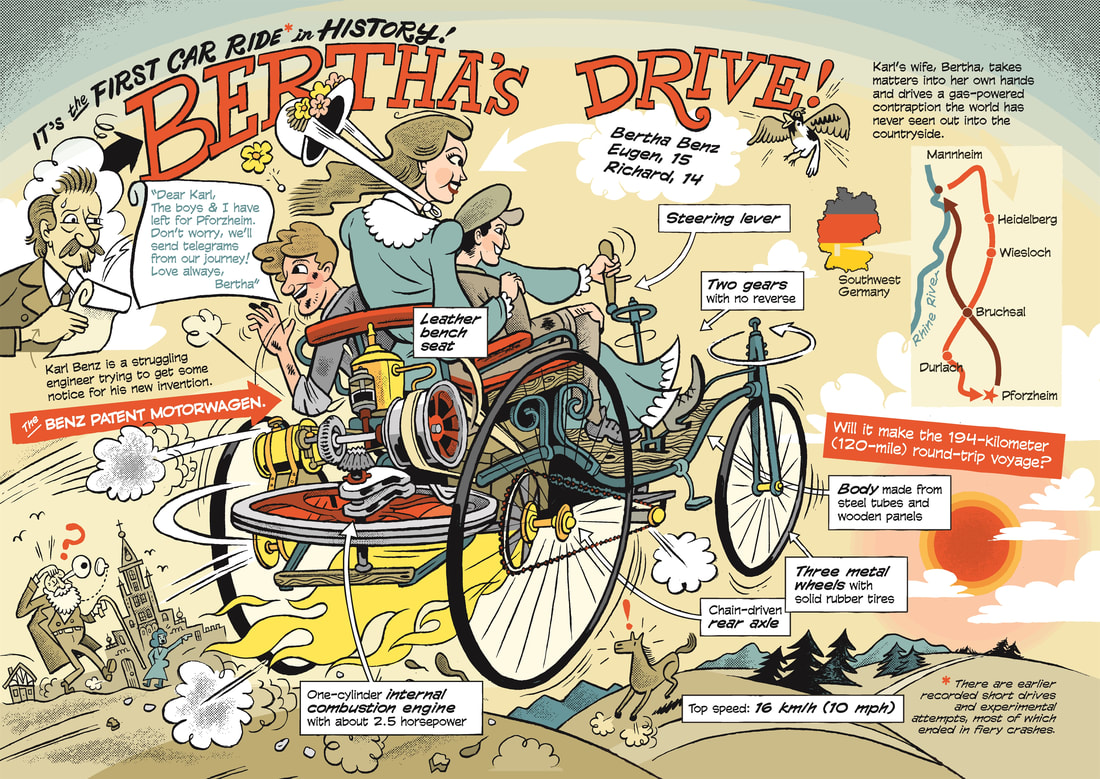

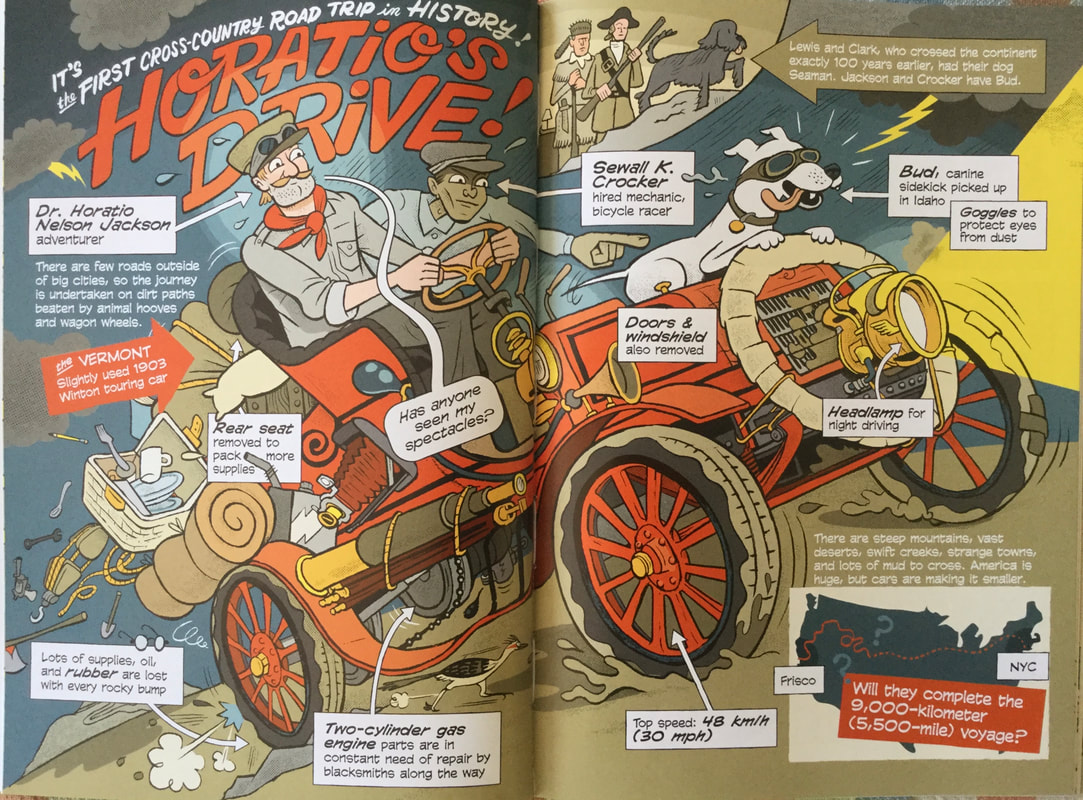

Science Comics: Cars: Engines That Move You. By Dan Zettwoch. Edited by Dave Roman; designed by Zettwoch and Rob Steen. ISBN 978-1626728226 (softcover). 128 pages. $12.99. First Second, May 2019. This one came out in 2019, but I missed it. As much as I dig publisher First Second, I’ve skipped over Science Comics, their didactic middle-grade nonfiction series on topics ranging from dinosaurs to robots, rockets to trees. I should have been paying attention, since the series, launched in 2016, has yielded nineteen books (and counting) and looks like a solid hit. Under editors Casey Gonzalez and (now just?) Dave Roman, Science Comics has welcomed diverse artists and writers, yet the books are strongly branded, sharing a common dress and size (128 pages). Collectively, the series is quite an editorial achievement, as opposed to the creator-driven work First Second usually champions. I suppose that’s one reason I’ve stayed away — but also, I admit, I share the general distrust of children’s informational nonfiction, a critically unloved genre despite outstanding work by creators like David Macaulay (and despite how much time my family and I have spent poring over DK Eyewitness Books). Expository nonfiction for young readers is often slighted as functional, utilitarian stuff, and it’s true that nonfiction books of the Baby Professor type — mechanical and unlovely — are everywhere. I tend to look askance at books that ignore or instrumentalize the pleasures of character and plot. So it took a great cartoonist to get me to try, at last, Science Comics: Dan Zettwoch. I first read Zettwoch in the avant-comix anthology Kramer’s Ergot, then followed him to his first graphic novel, the neglected Birdseye Bristoe (2012), and to Amazing Facts and Beyond (2013), a bundle of mock-didactic, believe-it-or-not strips in collaboration with Kevin Huizenga. Zettwoch’s work is distinctive and, for me, always a draw. He is the master of the cutaway diagram, the cartoon schematic, the absurd yet precise infographic: a successor to both Rube Goldberg and Robert Ripley. Somehow, he manages to be meticulous and loopy at the same time. What’s more, his work often pays tribute to bygone technologies by showing just how they worked. Zettwoch’s cartooning peers into the mechanics of things, rendering them with clarity and joy — so an informational comic about cars would seem like a natural for him. It is. While Science Comics: Cars boasts a few recurring characters who age over the course of the book, it’s not a character-driven narrative; unlike, say, a Magic School Bus adventure, or (I gather) some other Science Comics, it’s not framed as an individual or group journey. The recurrent figures are reminders of the book’s historical through-line, but mainly Cars is a workout for Zettwoch the diagrammer. Though automotive history gives the book an arc and shape, Cars comes closer to encyclopedic Eyewitness style than to a graphic novel. It’s a reminder that comics do not always need traditional strong “storytelling” in order to engage us the way stories do. The book may be organized thematically but coheres graphically. Zettwoch divides the book into four chapters, or “strokes,” named for the modern internal combustion engine’s four-stoke cycle: Intake, Compression, Power, Exhaust. Within these, he repeats certain graphic elements that together lend a sense of order; that is, the book finds its form by braiding and varying key images, layouts, and design conceits. For example, the first two chapters both begin with accounts of historic automobile rides that serve to establish phrases and layouts that recur later. At the same time, Zettwoch throws in, unpredictably, myriad diagrams, charts, and sly jokes, and this graphic playfulness turns Cars into a series of discrete spreads that almost stand by themselves, poster-like. The book demonstrates comics’ diagrammatic nature and the power of design to cluster and clarify big gobs of information — but it also gets a bit drunk on the sheer pleasures of the page. Cars is densely informative, and a feat of design. It excels at the engineering history of autos — but less so, alas, at the social. The book wants stronger thematizing: some social and political threads that would make it, in the end, more than a compendium of wonders. The final chapter, Exhaust, hints at deeper themes, discussing fossil fuels and noxious emissions; belatedly, it suggests the damage automobiles have done to the environment (the globe is shown wreathed by auto exhaust). I figured I was being set up for a reflection on the harm as well as advantages bred by cars — but, no, Zettwoch skitters in other directions, devoting four pages to an insanely detailed chart of trucks, another spread to “Weird Cars,” and then other pages to the histories of car horns, car stereos, etc. A final section covers electric cars and the possibility of driverless cars but gives no sobering sense of the challenges posed by car culture and our reliance on personal vehicles, no sense of ecological or social consequence. Nor does the book deal in detail with automotive safety. It’s as if it can’t face up to harder issues. Instead, it’s a blithe valentine to cars that any gear monkey could love. I get a sense of failed follow-through and of implications left unexplored — that is, I found the book’s finale disappointing. To his credit, Zettwoch’s version of car history is fairly inclusive, honoring women as engineers and innovators and spotlighting non-white figures as well. The book offers a bright, affirming view of a shared car culture. Yet Cars does not come to terms with what the overabundance of autos might mean for our common future. Zettwoch’s love of automotive engineering comes through, but the “science” part of the project feels incomplete without reckoning on the environmental impact of automobiles. Road not taken? Opportunity lost, I'd say. That said, Cars remains a dazzling exercise in show-and-tell, a master class in comics as diagramming and design. Though it may not quite add up, it overflows with ingenuity and pleasure. As it turns out, Science Comics can be interesting comics indeed. I’ll read more, with hope.

Update, June 29, 2020: Due to a technical or information-security problem, the Eisner Award voting has been restarted from scratch on a new online platform, and the new deadline for votes extended until tomorrow, Tuesday, June 30, at 11:59pm Pacific. Reportedly, voters who previously cast a ballot have been sent emails inviting them to vote again. I'm voting again at this very moment! Voting for this year’s Will Eisner Comic Industry Awards (the Eisners for short) will soon end, so file this post under "belated." Sigh. Unfortunately, the current COVID-19 lockdown and related stresses have slowed me down, so this comes late.  But: onward. This year’s list of Eisner nominees (announced on June 4) is another extraordinary snapshot of a (as ever) divided field that encompasses multiple, sometimes divergent, communities, a field that often feels like many fields at once. Having been an Eisner judge (2013), I can attest to what a joy and challenge it is to access, read, and debate so many different kinds of comics with other judges assembled from several different disciplines. If the final results of the Eisner voting are often an index of popularity, or simply of the kinds of comics that get noticed readily in shops, the ballot is less predictable and more expansive, reflecting the painstaking efforts of longtime Eisner Award Administrator Jackie Estrada and the diverse, carefully-selected judging panels she recruits. Those panels are typically balanced to include comics creators, retailers, journalists, critics, and scholars, and, once recruited, are fully autonomous and, in my experience, absolutely honest about what they like and don’t. It’s a great, once-in-a-lifetime gig. In my case, I spent a long weekend in a San Diego hotel conferring with my fellow judges. This year’s panel, however, has had to judge remotely, connecting via social media and Zoom (I can’t imagine). The process reportedly took two months longer than usual. But the panel sounds like it was an amazing group: journalist and scholar Jamie Coville; graphic novel reviewer Martha Cornog; my friend, scholar/teacher/designer Michael Dooley; comics writer and novelist Alex Grecian; podcaster and Comic-Con volunteer Simon Jimenez; and retailer and festival organizer Laura O’Meara. Michael has some telling comments and reflections on this year’s process, and his own values and priorities as a judge, in a PRINT magazine interviewer with Steven Heller that came out last week (worth a look). I agree with Michael that the list of nominees is the important thing, “the news that readers can most usefully use”; like him, I didn’t particularly care about who won the final voting, but loved taking part in the crafting of the ballot. This year’s list is an excellent and illuminating guide to this particular moment in comics. As I said, the comics community often feels like several disparate communities: different, even conflicting, publics and aesthetic formations. The Eisners, unlike guild awards such as the Oscars or Tonys, are voted on by a wide, dispersed group not held together by membership in a professional body, and the judging and voting processes reflect that. Jackie Estrada has deliberately set out to recruit diverse judges that can represent some of the many publics that make up the comics field and yet can also dialogue across boundaries and bring some focus to the awards. The continuing excellence of the yearly ballots bears out the wisdom of her efforts – congratulations, once again, to the judges and Jackie for a job well done! Of particular interest to KinderComics are the nominees in the young readers’ categories, and this year they’re terrific: Best Publication for Early Readers

Best Publication for Kids

(I confess to some disappointment here. Where is Luke Pearson's Hilda and the Mountain King? Where's Jen Wang's superb Stargazing?) Best Publication for Teens

I also want to note that Lois Lowry’s classic dystopia for young readers, The Giver, has been adapted by P. Craig Russell into a graphic novel nominated in the category Best Adaptation from Another Medium. In addition, children’s and YA comics creators were nominated in several other categories:

A few more observations: All told, there are some 180 Eisner nominees this year, spread over thirty-one categories (again, the full list is here). This year’s judges have moved even farther afield that usual, testifying to the increasing impact of not only children’s and YA comics but also digital comics, native webcomics, and other sectors beyond the traditional comic book shop. The ballot strays off the usual beaten paths and is an education in itself. While there are a number of categories in which I do not have a strong opinion (teaching through the pandemic has curtailed my comics reading these past few months), I’m greatly impressed by the lists for Best Short Story, Best Webcomic, Best Archival Collection/Project—Strips, Best Graphic Album—New, and the three journalistic and scholarly categories: Best Comics-Related Periodical/Journalism, Best Comics-Related Book, and Best Academic/Scholarly Work. In fact, I just have to list the nominees in the following three categories, which are incredible: Best Academic/Scholarly Work(This is a great year for comics studies titles. Dig the diversity of topics and publishers!)

Best Webcomic(As soon as the ballot came out, I went and read or re-read all the nominees, Wow!)

Best Short Story(Again, a rich, revelatory list!)

Finally, I commend the judges for inducting artists Nell Brinkley and E. Simms Campbell into the Eisner Hall of Fame, and for nominating fourteen others, out of which four will be inducted by the voters: Alison Bechdel, Howard Cruse, Moto Hagio, Don Heck, Jeffrey Catherine Jones, Francoise Mouly, Keiji Nakazawa, Thomas Nast, Lily Renée Peter Phillips, Stan Sakai, Louise Simonson, Don and Maggie Thompson, James Warren, and Bill Watterson. (That’s a hard list to choose from!) A final note: The Eisner winners were to be have been announced at the usual gala ceremony on Friday night (July 24) during the San Diego Comic-Con; now, however, they will be announced online instead, sometime in July I hear, most likely as part of Comic-Con@Home. Details TBA.

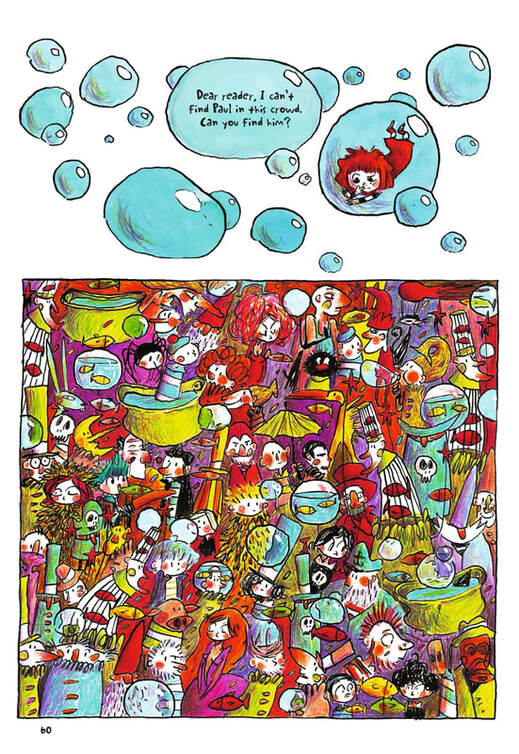

The Runaway Princess. By Johan Troianowski. Translated by Anne and Owen Smith; designed by Patrick Crotty. RH Graphic, ISBN 978-0593118405 (softcover), $12.99. 272 pages. January 2020. The Runaway Princess, a giddy, self-aware romp, celebrates doodling, play, and spontaneous worldbuilding. Its title and cover may suggest a feminist fractured fairy tale of the Princess Smartypants variety, but it’s really a Baron Munchhausen sort of yarn, a happy riot whose main lesson is pleasure. Not so much a deliberate novel as a spree, it showcases author Johan Troianowski’s freewheeling cartooning while riffing on familiar stuff. The first release under RH Graphic, Random House’s new comics imprint, The Runaway Princess translates Troianowski’s French series Rouge (2009-2017). The Rouge of the original becomes Robin here; she’s a wayward young adventuress with a touch of Little Red Riding Hood but also Pippi Longstocking. The world she travels is a vehicle for exuberant drawing and vivid, crayon-and-ink coloring. It’s also chockablock with drive-by homages to children’s literature, from classic fairy tales to Alice to The Wind and the Willows. Essentially, The Runaway Princess collects three rambling quests that consist of hide-and-seek, maze-walking, and casual discovery. In the first, Robin traverses a dark and threatening wood, where she befriends four lost kids, all boys, whom she leads out of the wood, to a strange city and festival. There some of the kids get lost again and have be found. In the second tale, Robin and the boys discover an underground world, where Robin befriends a witch, until the tale takes a darker, Hansel and Gretel-like turn; more hiding and chasing ensue. In the third, Robin and boys are cast away on an island, where a benevolent explorer introduces them to the culture of the Doodlers: small creatures who make art. Treasure-hungry pirates attack, and again the plot affords plenty of frantic running around. Notably, the book includes self-reflexive, interactive pages that invite the reader not just to read but to do things: solve mazes, shake the book, etc. That is, The Runaway Princess is a game of sorts; the book knows that it’s a book, and invites us to have fun with that fact. If Troianowski’s loose, scribbly style recalls Joann Sfar or Lewis Trondheim, his metatextual play recalls Fred’s classic Philemon series: as the plot bounces from one craziness to another, there’s little sense of danger or poignancy, more a benign, Fred-like absurdism and self-awareness. Troianowski excels at weird places—City of Water, Island of Doodlers—and favors graphic playfulness over tight logic, but it’s the direct appeals to the reader that make it work. Though The Runaway Princess would be at home alongside Philemon, or, say, Sfar’s Little Vampire, it lacks the philosophical weight of Fred and odd tenderness of Sfar, and sometimes reproduces Eurocentric, colonialist clichés (as in the ethnological Doodlers plot). Yet the book fizzes like a rocket, and cheerfully celebrates creativity (in this, it resembles, say, Liniers’s Written and Drawn by Henrietta). In sum, it’s is a breezy, inventive launchpoint for RH Graphic, and recommended.

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed