|

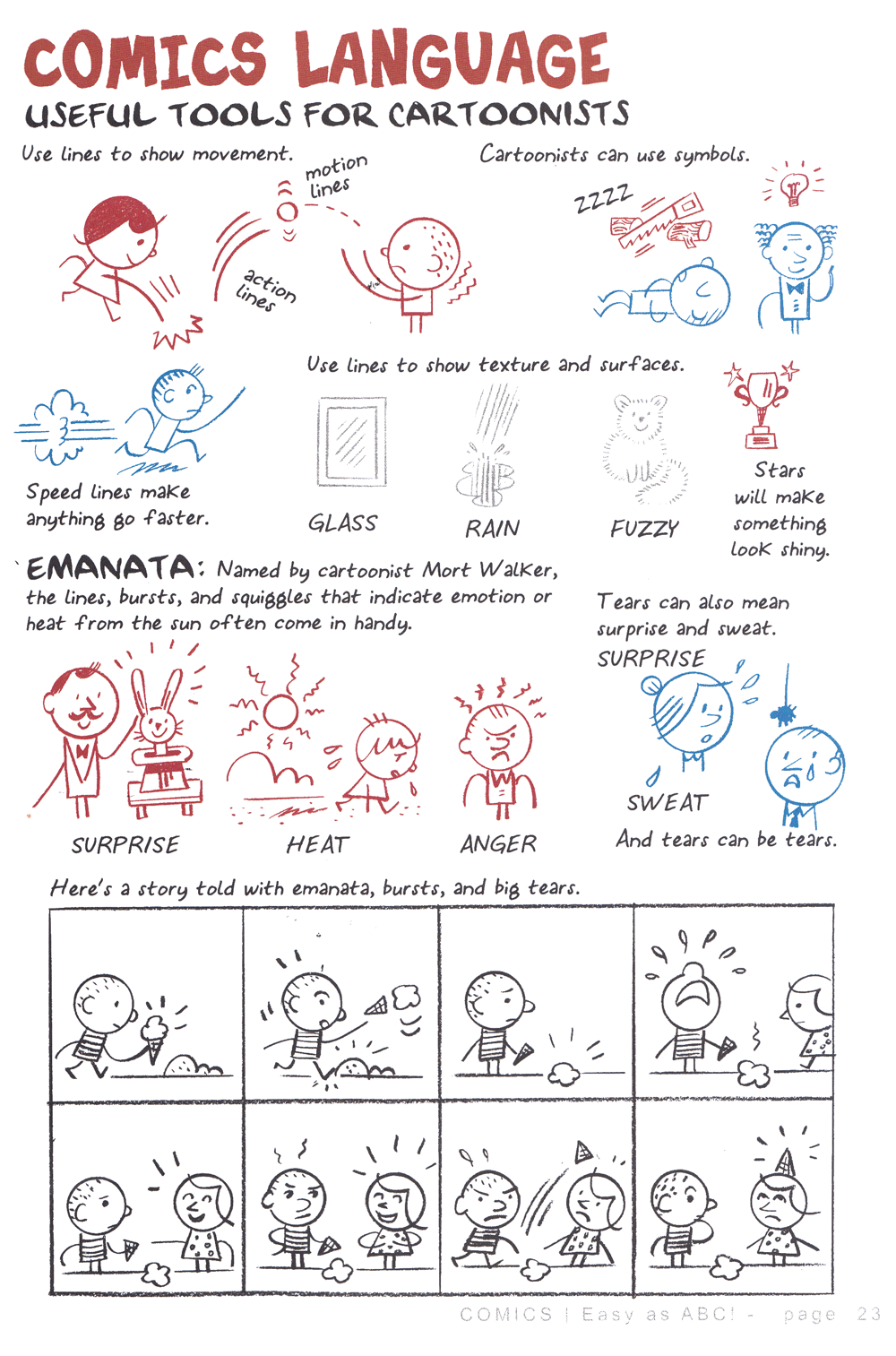

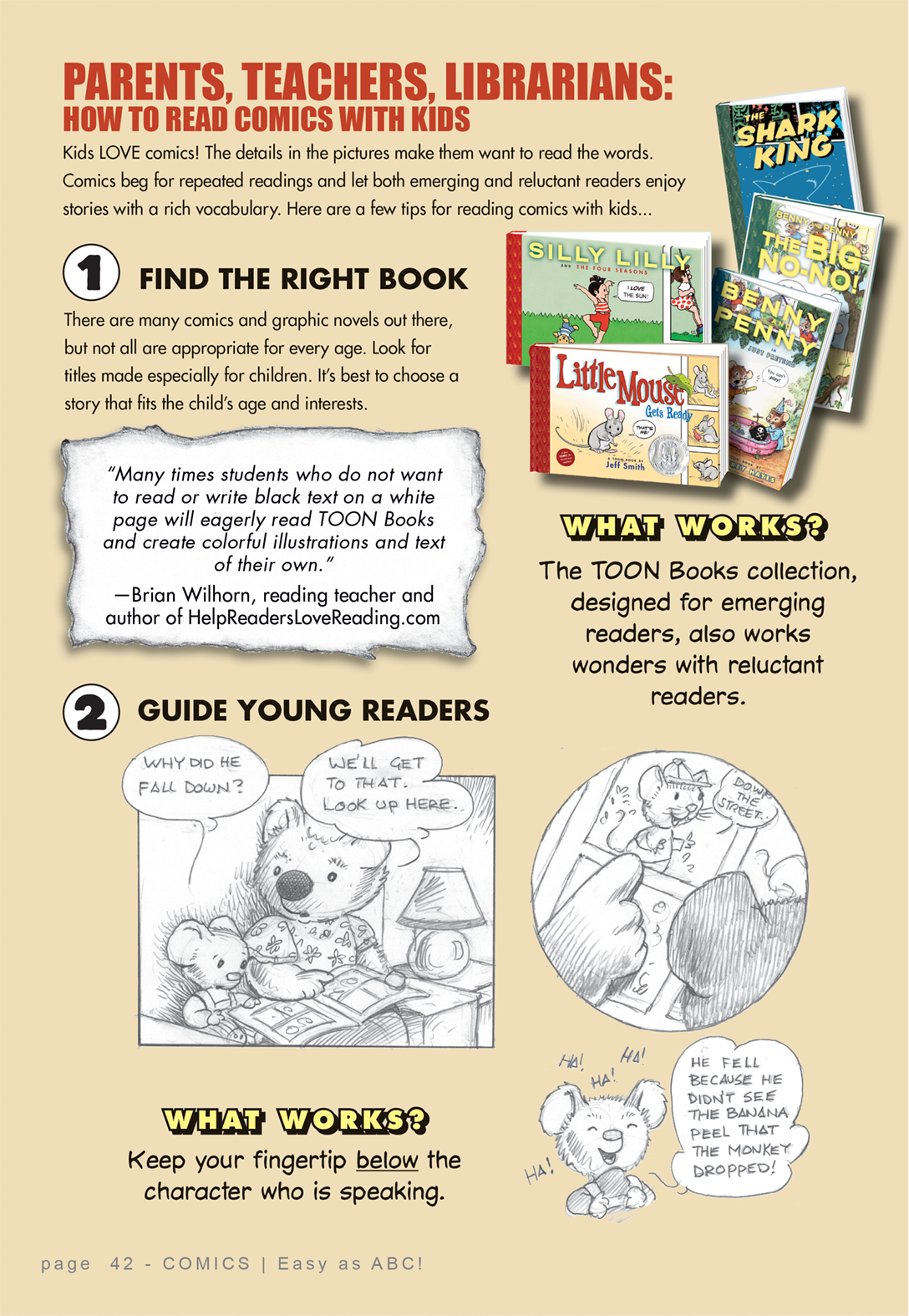

Comics: Easy as ABC! By Ivan Brunetti. Edited and designed by Françoise Mouly. With contributions by Eleanor Davis, Elise Gravel, Geoffrey Hayes, Liniers, Sergio García Sánchez, Art Spiegelman, and others. TOON Books, 2019. ISBN 978-1-943145-39-3 (softcover), $9.99; ISBN 978-1-943145-44-7 (hardcover), $16.95. 52 pages. A Junior Library Guild Selection. This is meant to be a book "for kids." I'll be using it next term as a textbook in a college class. That ought to tell you something. Comics: Easy as ABC! is both a book by Ivan Brunetti and a showcase for the entire TOON Books line. Not for nothing does the spine say Brunetti/Mouly, pointing to the crucial role of TOON's editorial director, Françoise Mouly, who commissioned, edited, and designed the book, drawing on a who's who of TOON authors to complement and fill out Brunetti's text. I imagine that this book was her idea; I note that it reuses the "coaching tips" for parents and educators found on TOON's website. In any case, Comics: Easy as ABC! works as both a young reader's adaptation of Brunetti's pedagogy, as modeled in his previous instructional book Cartooning: Philosophy and Practice (Yale, 2011), and a distillation of Mouly's (and TOON's) editorial ethos. That ethos brings kid-friendly storytelling and cartooning into contact with frank avant-gardism (shades of The World Is Round!). Who would have thought that Brunetti, author behind the scabrous, post-Crumbian Schizo and other bitter, depressive, and often savage alt-comix, would become one of TOON's signature authors, and an ambassador for children's cartooning? The mind reels. But the role suits him, and his methods can help adults as well as kids. Anyone who has carefully read (or has taught) his Cartooning textbook knows that his pedagogy is precisely the sort to encourage those who "can't draw"; Brunetti extols comic art not as illustration but as a form of "writing with pictures" accessible to almost everybody. Whereas Cartooning imagines itself as a syllabus crafted by an authoritative (and strict) teacher with a classroom of official students, Comics: Easy as ABC envisions an audience of free-spirited kids with time on their hands, doing what they want to do. A comparison to Lynda Barry's new Making Comics may help: whereas Barry exhorts her adult students and readers to recover the openness and energy of childhood drawing, Easy as ABC aims right at kids themselves (though with imagined grownups peeking solicitously over the kids' shoulders, as it were). The result is a dual-purpose book: part how-to for a young (or any aspiring) cartoonist, part exhortation to "parents, teachers, and librarians." Woven through Brunetti's pages of advice and demonstration are miscellaneous contributions from other cartoonists, with those by Elise Gravel, Sergio García Sánchez, Art Spiegelman, and the late Geoffrey Hayes being perhaps the most substantial. Benny and Penny pages by Hayes, endpapers by Gravel, a draw-your-own-conclusion strip by Spiegelman, a (too dense?) page on perspective by García Sánchez—the book is filled with diversions. Short, elliptical strips by various artists from the 4PANEL Project website insinuate an art-comics vibe by means of a traditional comics structure. Sprinkled here and there throughout the book are blurbs labeled "What works?" that offer advice either to artists or to adults coaching children through comics-reading. It's a Whitman's Sampler on the surface, a deliberate curriculum underneath. All the "extras" are good, but what most matters to me is Brunetti's teaching method. Mixing brief texts with scads of drawn examples, he starts the budding cartoonist with encouragements to doodle and experiment with basic shapes and free mark-making. He then progresses to faces, emotions, schematic character design, bodies, body language, and point of view. Eventually he gets to comics-specific devices such as emanata, word balloons, and page layout (the back matter includes an index of comics terms). Brunetti's approach is disarmingly accessible, without stinting on specific vocabulary and questions of technique. This is why I want to use this book in my university Comics class: even more than Brunetti's Cartooning, this book lays out, very clearly, basic storytelling and craft conventions that my students will need to think about as they prepare their final comics projects (and the various short exercises that will lead up to and scaffold those projects). I could quibble with some of the book's claims. Consider, for example, this exhortation to rapid-fire doodling: “When we have no time to think about the drawing, we get closer to the idea of the thing being drawn” (6). This idea that the quiddity or basic “whatness” of a thing is best conveyed without fussiness or craft, and without worrying about how to capture its visual particularities, fits Brunetti’s favored notion of comics as picture writing, but seems to deny the importance of observational drawing or the evocative this-ness of a distinctive drawing. At times, Brunetti’s advice seems designed to steer artists toward semiotically handy visual cliches. This is consistent with his ethos of writing over illustrating, and is likely to be liberating good advice for up and coming artists, but it soft-pedals the considerable effort often required to find distinctive, personal ways of rendering things as cartoons. If you believe that eloquence and distinctiveness of drawing are important, Brunetti’s embrace of simplicity and very familiar forms may grate on your nerves. On the other hand, I have given similar assurances to students in my (emphatically non-studio) classes (i.e. English classes), and I find that this sort of advice and exhortation does indeed serve to unlock visual storytelling. So, I dunno, maybe I should keep my big trap shut. In any case, I will be using this book next term! I expect it will be a great guide. It’s also a delightful read on its own terms, and a summation of what makes TOON Books such a terrific publisher.

0 Comments

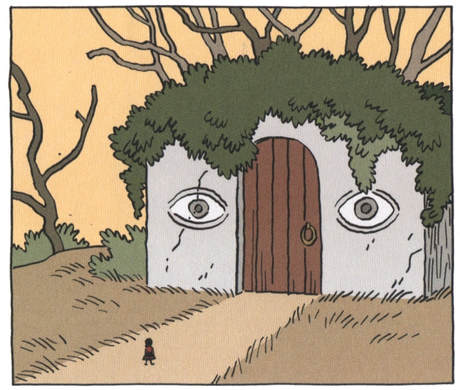

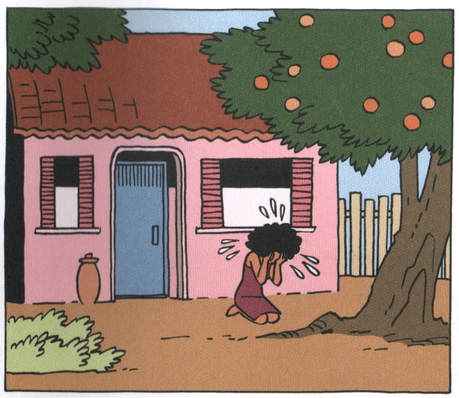

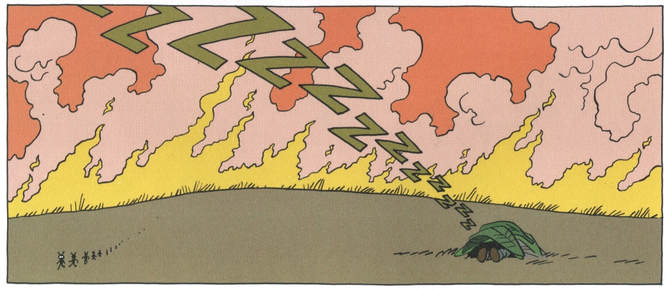

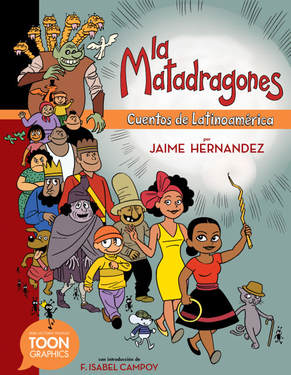

The Dragon Slayer. By Jaime Hernandez. TOON, 2018. Hardcover: ISBN 978-1943145287, $16.95. Softcover: ISBN 978-1943145294, $9.99. 40 pages. A Junior Library Guild Selection.Jaime Hernandez, one of the world's great cartoonists, is as lively and influential a comic book artist as you could hope to find. He has changed many readers' and artists' lives. His work on the Love and Rockets series (1981-now), in tandem with his brothers Mario and especially Gilbert Hernandez, proved that there was life and juice and relevance in the serial comics magazine, beyond even what many fans of the medium had dared hope. The punk, Latinx, and queer-positive aesthetic of L&R, along with its serious, in-depth storytelling and formal risk-taking, made for a revolution in comics, and Jaime Hernandez has deservedly been called one of the masters of the medium. The Dragon Slayer is not his first comic for children, as he's done a few short pieces for children's anthologies. Nor is it his first comic based on folklore: seek out for example "La Blanca," his version of a ghost story he heard from his mother, which he did for Gilbert's all-ages anthology Measles No. 2 back in 1999 (Gilbert too has made folk and family lore into comics: dig his "La Llorona," from New Love No. 5, back in 1997). Moreover, children and childhood memories are essential to Jaime's work in Love and Rockets. But The Dragon Slayer is Jaime's first real children's book. I have kid [characters] in my adult comics, but they play by my rules. Now that I’m writing for children, I’m playing by their rules. I was a little nervous because now I’m speaking directly to kids and to the parents who will let them read [the book]. So Dragon Slayer is something new for him. In fact it's a quiet collaboration: the book's back matter tells us that Hernandez read through many folktales to find the three that he wanted to adapt, and in this he was commissioned and helped by TOON's editorial director and the book's designer, Françoise Mouly. Mouly's team also deserves mention: in this case, designer Genevieve Bormes, who supplied Aztec and Maya design motifs that enliven the book's endpapers and peritexts, and editor, research assistant, and colorist Ala Lee. Like most books in the TOON Graphics line, Dragon Slayer includes some discreet educational apparatus, in the form of notes and bibliography -- more teamwork. Further, the book comes introduced by prolific scholar and children's author F. Isabel Campoy, whose collaborative book with children's author and teacher educator Alma Flor Ada, Tales Our Abuelitas Told: A Hispanic Folktale Collection (2006), is credited as one of Hernandez's sources. Campoy and Ada are key contributors here. (Another key source, albeit not as clearly announced, is John Bierhorst's 2002 collection Latin American Folktales.) All this is by way of packaging three 10-page comics by Hernandez, which are a delight, and are over too soon. I could read book after book like this from Hernandez -- the premise fits him beautifully. Hernandez has said that he liked the "wackiness" of these stories, and they do have that absurd-but-perfect, unquestionable quality of many folk tales: a sense of symbolic rightness and fated, almost-inevitable form in spite of the seeming craziness of their plots. Things happen that are preposterous and unexplained but just seem to fit, to click, because of the tales' use of repetition, parallels, rhythmic phrasing, and ritual challenges: stock ingredients, in anything but stock form. These folkloric patterns make the tales complete and rounded no matter how nonsensical they might appear at first. In crisp pages that rarely depart from a standard six-panel grid, Hernandez delivers the stories straight up, without any rationalizing or ironic distance, in clean, classic cartooning that communicates without breaking a sweat. Jaime is a master of seemingly guileless and transparent, but in fact subtle and artful, narrative drawing, and The Dragon Slayer does not disappoint. This has been billed as a "graphic novel," but it's no more a novel than other splendid TOON books like Birdsong, Flop to the Top, The Shark King, or Lost in NYC. What it is is a charming comic book that whets the appetite for more. Hernandez's cartooning benefits from the book's folkloric and scholarly teamwork, but the main thing is that the comics are marvelous. The title story, a feminist fairy tale with a light touch, focuses on an unfairly disowned youngest daughter who slays monsters and solves problems: a real pip. "Martina Martínez and Pérez the Mouse" (adapted from Ada's text) is an absurd story of marriage between a woman and a mouse, until it becomes a wise fable about panic and grief. "Tup and the Ants" is a lazy-son story in which the (again) youngest child proves his mettle with the help of a hill's worth of hard-working ants. All three comics surprised me and made me laugh out loud. I could call the book an anthology of lovely moments. It suffers no shortage of arresting moments -- panels that leap out: But what really makes these panels lovely is that there is no grandstanding in the art, only a terrific economy in visual storytelling: a streamlined delivery that carries us far, fast. Context is everything, and the book is not so much excerptable as endlessly readable. In short, The Dragon Slayer is a great book for Jaime Hernandez and for TOON, and one of the best folktale and fairy tale-based comics I've seen. I confess myself puzzled by its labeling as a TOON Graphic, which in the TOON system implies an older, more experienced comics reader, as opposed to TOON's Level 1, 2, and 3 books for beginning or emerging readers (I don't see this as a more complex comics-reading experience than, say, some of the Level 3 titles). But I do appreciate the oversized (7¾ x 10 inch) TOON Graphics format, which gives Hernandez a larger space to work in, more like that of a comics magazine. That suits his drawing and pacing. In any case, The Dragon Slayer is a sweet, short burst of smart, loving comics, and comes highly recommended. PS. A Spanish-language edition, La Matadragones: Cuentos de Latinoamérica, is also available in both hardcover (ISBN 978-1943145300) and softcover (ISBN 978-1943145317), priced as above. TOON provided a review copy of this book, in its English-language version.

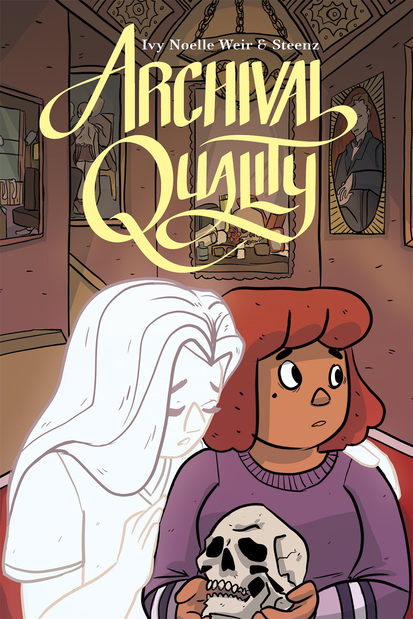

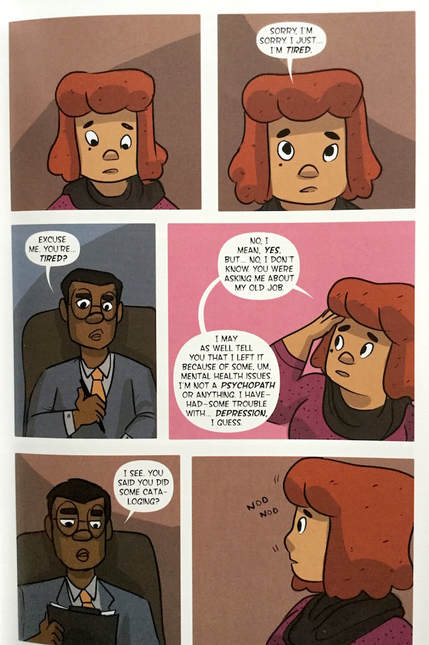

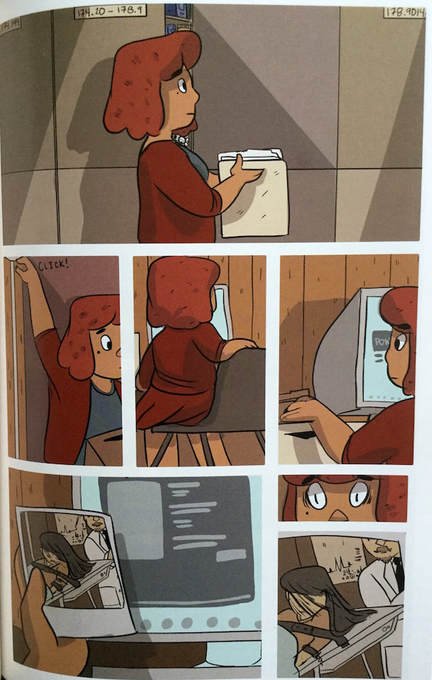

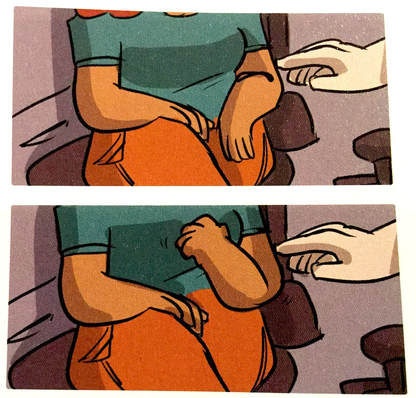

Archival Quality. Written by Ivy Noelle Weir, illustrated and colored by Steenz. Oni Press, March 2018. ISBN 978-1620104705. $19.99, 280 pages. A Junior Library Guild Selection. Archival Quality, an original graphic novel out this week, tells the story of a haunted museum: a ghost story. It also tells about living with mental illness. The protagonist Cel, a librarian struggling with anxiety and depression, takes a job as archivist of a spooky medical museum that once served as an asylum (my friend, medical archivist and comics historian Mike Rhode, should check this out). The catch: she has to live in an apartment on the premises and do her work only in the dead of night. Soon she begins to witness... happenings that she cannot explain. Her boss, the museum's curator, and her coworker, a librarian, tiptoe around her, knowing more than they will say. Cel, who lost her previous job due to a breakdown, is understandably perplexed and triggered by their evasions, and by the fact that no one seems to believe her reports of odd doings. She begins to have frightful dreams: flashbacks that evoke the shadowy history of women's mental health treatment. The plot, which like many ghost stories gestures toward the fantastic (as Todorov defined it), finally veers toward the outright marvelous as Cel investigates the case of a young woman from long ago whose presence still lingers about the place. Cel, as she works to solve that case, is by turns fragile and angry, defensive and determined—a complex character, as is the curator, at first her foil, later her ally. The story takes quite a few turns. To be honest, Archival Quality's title and look did not prepare me for its uneasy exploration of mental health treatment—or rather, the social and psychiatric construction of mental illness. As I read through the novel's first half, Steenz's drawing style struck me as too light, undetailed, and schematically cute for the story's atmosphere of updated Gothic. Cel, with her snub nose, button eyes, and moplike hair, reminded me strongly of Raggedy Ann, and in general Steen's characters have a neotenic, doll-like quality. The settings seemed too plain to conjure up mystery and dread; the staging seemed too shallow, with talking heads posed before blank fields of color or swaths of shadow, lacking particulars. Steenz favors air frames (white borders around the panels, rather than drawn borderlines) and an uncluttered look. This did not jibe with my expectations of the ghost story as a genre. But as the plot deepens, and Cel's dreams and visions overtake her, Weir and Steenz together generate suspense. The pages deal out a number of small, quiet shocks: Further, Steenz's sensitive handling of body language brings the characters, doll-like as they are, to life. The book becomes tense, involving, and, as we say, unputdownable. Weir and Steenz's back pages tell us that the two enjoyed a close working relationship, and you can tell this from the story's anxious unwinding. This is unusually strong storytelling, and a complicated, coiled plot, for a first-time graphic novel team. Clearly, Weir and Steenz are simpatico artistically—and ideologically too, I think, sharing a progressive and feminist outlook that shapes cast, character design, characterization, and plot. I will admit that not everything about Archival Quality works for me. The plot, on the level of mechanics, seems juryrigged and farfetched, that is, determined to pull characters and elements together for the sake of symbolic fitness, without the sort of realistic rigging that the novel seems to be striving for. In other words, certain things happen simply because they have to happen. Further, some elements of the story, rather big elements I think, are palmed off in the end because Weir and Steenz don't seem to be interested in working out the details. At the closing, I had the feeling that a Point was being made, rather than a novel being rounded off (to be fair, I often react this way to YA fiction, even though I know that didacticism is crucial to the genre). Still, Archival Quality, behind its coy title, offers a gutsy exploration of mental health treatment, an eerie ghost story, and characters who renegotiate their relationships with credible human frailty and charm. A most promising print debut, and a keeper.

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed