|

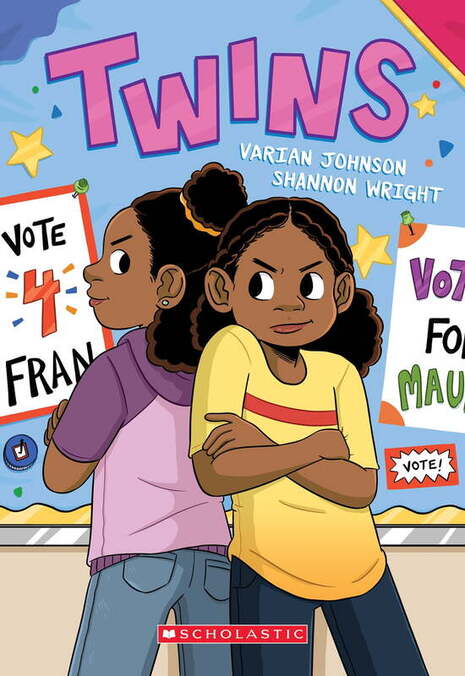

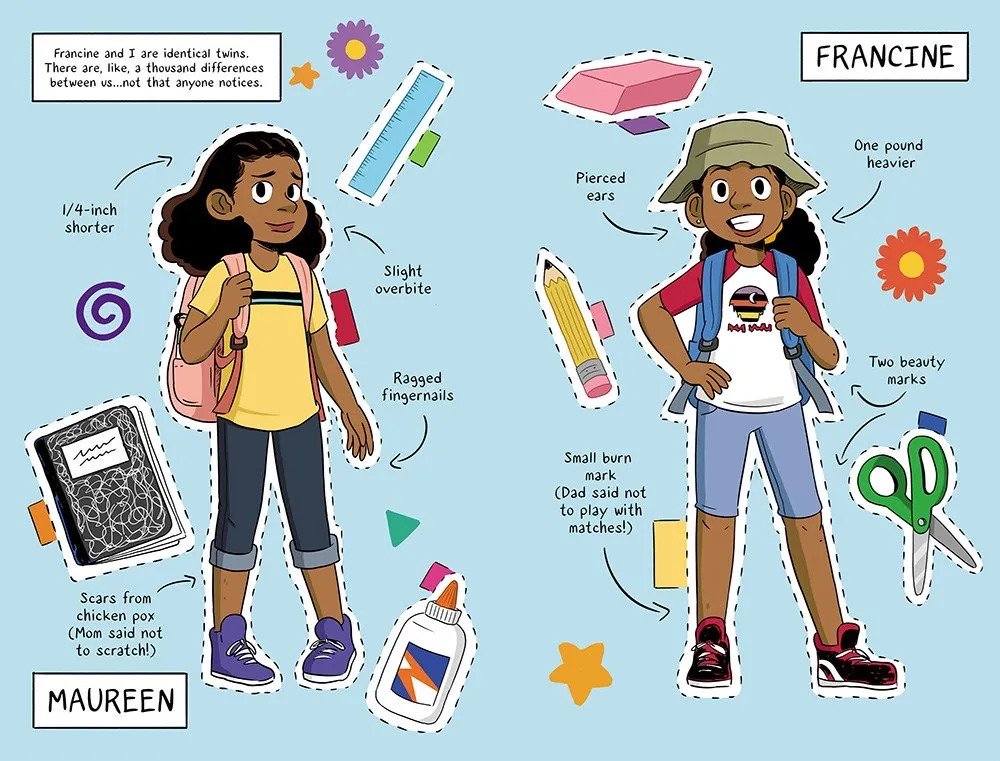

Twins. By Varian Johnson and Shannon Wright. Scholastic/Graphix, ISBN 978-1338236132 (softcover), 2020. US$12.99. 256 pages. Last week I belatedly read Twins, a much-praised middle-grade graphic novel published by Scholastic in 2020 — a first graphic novel for both writer Varian Johnson, who is a prolific novelist, and artist Shannon Wright, who has illustrated a number of picture books (most recently, Holding Her Own: The Exceptional Life of Jackie Ormes). Twins is good, but left me wanting more. The plot concerns identical twin sisters, Maureen and Francine, who have always been close but begin to pull apart as they enter sixth grade. They end up running against each other in a student body election, a rivalry driven by mixed or confused motives that hurts their relationships with friends and family. The book boasts many nicely observed, sometimes poignant, details: novelistic good stuff. The plotting balances the twins' need for individuation against their strong bond, with a sense of earned insight for both sisters. There are astute cartooning choices along the way, including full-bleed splash pages that capture moments of struggle, hurt, and growing realization. Compositionally, Wright delivers, with emotive characters, startling page-turns, and a confident grasp of what's at stake dramatically. Twins, I admit, strikes me as more reassuring than challenging. It's on familiar middle-grade turf, with a story of girls becoming tweens and growing more sensitized to social nuances and strained friendships. There are soooo many graphic novels currently working this turf. The setting is anodyne: a comfortably middle-class suburbia with dedicated students, supportive teachers and families, wise parents, and lessons on offer about self-discipline, self-confidence, and leadership. Loose ends are tied and every arc resolved, or at least reassuringly advanced, by book's end, with no one coming off the worse. Some elements, however, seem under-thought or cliched — for instance an ROTC-like "Cadet Corps" at the school, a plot device that allows for a fierce, drill sergeant-like teacher and moments of tough discipline for the more timid of the two sisters, who of course comes out the stronger (but oh the unexamined militaristic overtones). The book is inclusive and aims to be progressive, focusing on protagonists of color (Maureen, Francine, and their family are Black) while downplaying the usual generic thematizing of racism and classism as "problems" to be suffered through (a tendency expertly spoofed by Jerry Kraft in New Kid). One scene deals with shopping while Black and implies a critique of unspoken racism, but that thread isn't woven through the whole book. That in itself might be refreshing; the book thankfully avoids potted depictions of racialized suffering and trauma. Yet for me there is too little sense of social or institutional critique; the twins' relationship and personal growth are the main things, to the point of presenting adult choices uncritically and tying up the story without any lingering sense of mystery or depths remaining to be plumbed. In a word, it's pat. Perhaps I'm guilty of wanting this middle-grade book to be more YA? That wouldn't be fair, of course. But Twins is one of so many recent graphic novels that, from my POV, appear boxed in by children's book conventions, more specifically by the rush to affirm and reassure. The contours of this kind of book are starting to seem not just clear, but rigid. Young Adult books too have their conventions, one being skepticism of adult choices and institutions, and I don't know if I'm asking for that. Perhaps what I'm wishing for is something else: a touch of mystery, maybe, or a respect for the unfinished business of living. Twins is a traditional tale well told, with all its arcs well finished and its major characters affirmed and advanced. I just can't imagine re-reading it for pleasure. Some readers will stick to the book like glue, I expect. The characterization of the twins is complex, and Maureen, who is the book's focal character and real protagonist, is especially well realized: a socially anxious nerd and academic overachiever but not a shrinking violet, not a cliché. Johnson and Wright know these characters and treat them kindly; their dialogue clicks. Plus, the art is full of smart touches, and Wright offers clear, crisp cartooning and dynamic layouts throughout. Some moments registered very strongly with me: for example, the scene early in the book where Maureen and Francine get separated at school and a page-turn finds Maureen stranded in a teeming crowd of other kids, lost. Yet the book's brightness and formulaic coloring, which favors open space, solid color fields, abstract diagonals, and color spotlights, strike me as simply functional, and in the end more busy than harmonious. While Wright excels at characters, the settings appear textureless and a bit bland. Her page designs are restless, inventive, and clever, the storytelling clear, yet the governing sensibility seems, again, generic to my eyes. It's right in the pocket for post-Raina middle-grade graphic novels, but doesn't grip me. The middle-grade graphic novel is one of the most robust areas in US publishing, and the novel of school, friendship, and social navigation is its nerve center. Twins is a fine example of that. I think I'm becoming more and more jaundiced about that kind of book, though. I can now see the outlines of a formula, and I'm getting jaded. I admit, this realization has me rethinking the bright burst of enthusiasm with which I began Kindercomics five years ago.

0 Comments

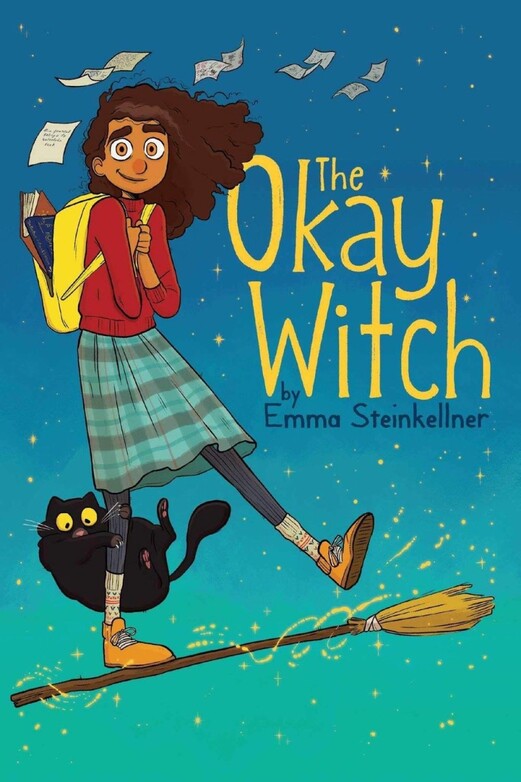

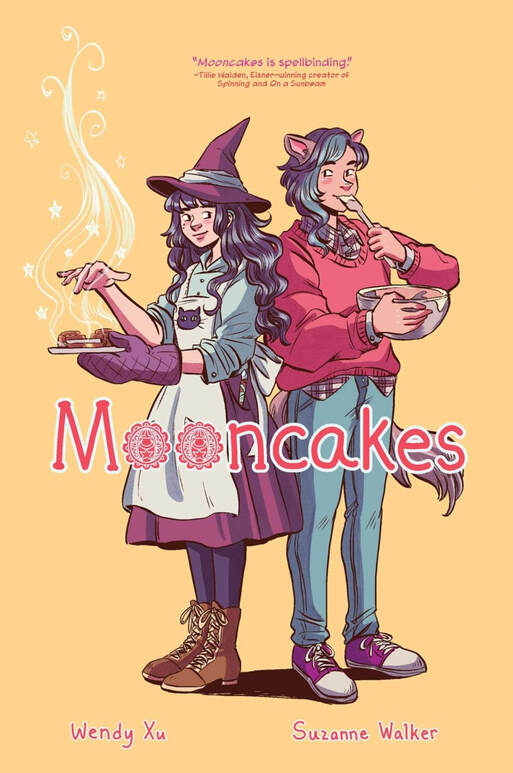

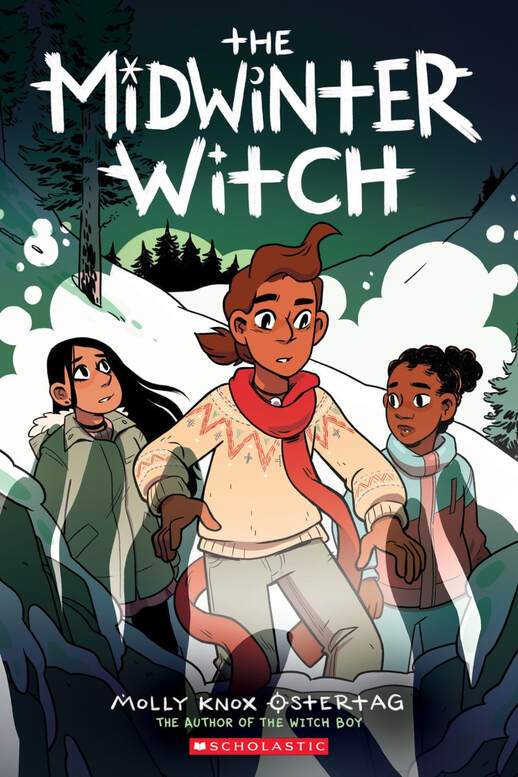

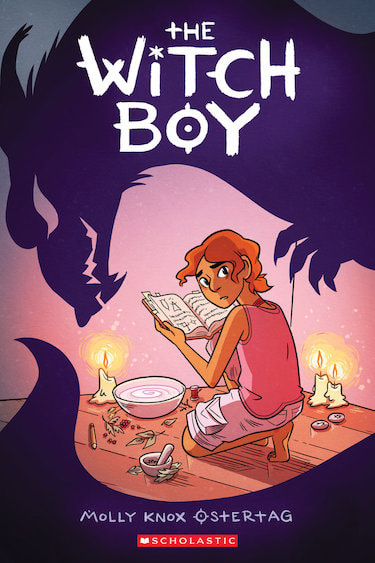

Coming-of-age stories about young witches have definitely become a genre in young readers’ graphic novels: a means of blending fantasy and Bildungsroman, and of telling stories about gender and sexuality, sometimes about other forms of difference, and about resistance versus conformism. Generally, these witch stories offer gender-conscious, often queer-positive, fables of identity. Post-Harry Potter, but often rejecting the Potter novels’ emphasis on passing in the mundane world, they also seem influenced by Hayao Miyazaki and the magical girl franchises of anime and manga. Here are reviews of three graphic novels about witches that came out, one after another, last fall: The Okay Witch. By Emma Steinkeller. Aladdin/Simon & Schuster, ISBN 978-1534431454 (softcover), Sept. 2019. 272 pages, $12.99. A girl named Moth, a misfit in her Salem-like town, discovers that she comes from a line of superhuman witches, her mother is more than three centuries old, and her family is entangled in the history of the town and its witch-hunters. Moth’s grandmother has retreated into a timeless, otherworldly utopia for witches, while her Mom has embraced the mortal world and sworn off witchcraft. Grandmother and Mom argue over Moth’s destiny, while Moth seeks her own way. There’s an intriguing story hook in this middle-grade fantasy, which poses an ethical dilemma about retreating from, versus engaging, an imperfect world — and suggests an allegory of America, in which women of color (Moth and family) expose and challenge the culture’s white-supremacist and patriarchal origins (the witch-hunters). However, The Okay Witch seems tentative and underthought, hobbled by blunt exposition, shallow characterization, and patchy drawing. Steinkellner’s characters are designedly cute and expressive (her style reminds me of Steenz), and she seems to grow into the work as she goes, but the results are unsteady. The breakdowns and staging of action sometimes confuse, the settings lack texture and depth, image and text do not always cooperate, and distractions such as crowded lettering and jumbled perspectives dilute the impact. The novel is progressive, hopeful, and charming, much more than the pastiche of Kiki’s Delivery Service suggested by its cover, but still strikes me as a derivative, uncertain effort. Mooncakes. By Wendy Xu and Suzanne Walker. Lettered by Joamette Gil; edited by Hazel Newlevant. Roar/Lion Forge, ISBN 978-1549303043 (softcover), Oct. 2019. 256 pages, $14.99. Mooncakes is a Young Adult fantasy about witches, werewolves, and demons, set in a world where magic is — well, not commonplace, but not unheard of either. More than that, it’s a gentle romance between two sometime childhood friends, now young adults: Nova, a witch who lives and works with her grandmothers (also witches); and Tam, a genderqueer werewolf and a refugee, running from cultists who seek to exploit their power. Even more, though, Mooncakes is a paean to community: a culturally diverse, queer one that helps Nova and Tam bind demons and face down their adversaries. The complicated plot hints at a world in which the relationships between technology and magic, humans and spirits, and the living and dead could take volumes to explore. Xu’s drawing is organic and expressive, her pages lively variations on the grid, with occasional dramatic breakouts. The settings are richly textured, the colors thick, a tad cloying. The emotional dynamics are enriched with grace notes of characterization (Xu and Walker know when to take their time). That Nova is hard of hearing is a point gracefully handled, neither central nor incidental. The story is finally a bit too pat, and reworks some shopworn elements — again, there’s that whiff of Miyazaki, with animal spirits and talk of a young witch’s apprenticeship. Yet the distinct characters and budding romance make it click. The Midwinter Witch. By Molly Knox Ostertag. Color by Ostertag and Maarta Laiho; designed by Ostertag and Phil Falco. Scholastic/Graphix, ISBN 978-1338540550 (softcover), Nov. 2019. 208 pages, $12.99. The Midwinter Witch rounds out Ostertag’s middle-grade Witch Boy trilogy — though I dearly wish this wasn’t the last book, since she has created such a beguiling world and winning family of characters. The series keeps getting better, and this volume hints at conflicts and potential that could sustain even deeper explorations. Here, Aster (the gender-nonconforming “witch boy”) and Ariel (a character introduced in the second book, The Hidden Witch) and their friends attend the Midwinter Festival, a yearly reunion of Asher’s extended family. There they compete in a tournament that requires each of them to face their fears: Aster’s of defying a strictly gendered tradition, Ariel’s of not fitting in, of being the orphan and odd witch out. Acerbic and defensive, Ariel is not sure she can become part of Asher’s very welcoming family. A dark force from her past looms up, luring her to a different path and leading to a confrontation that is all too quickly resolved — I wanted to know more about Ariel’s particular darkness and its source. The payoff, though, is lovely and affirming. The Midwinter Witch is a remarkably sure-handed work of cartooning, enlivened by deft, often silent, characterization, artfully designed pages that mix the grid with bleeds and multilayered spreads, and felicitous coloring. Overall, it’s a marvel of elegant, empathetic storytelling — a new high for Ostertag. By way of conclusion, I invite KinderComics readers with insights into this genre to weigh in with comments! I'd love to hear from readers with a strong interest in this kind of story; I'm eager to gain a fuller sense of the witch's tale, where it comes from, and what it might mean for culture and for comics. I see literary, cinematic, and anime/manga influences in this genre, but still find myself wondering, why is the witch's tale flourishing now, as a comics genre? How does the treatment of the witch's tale in comics differ from its treatment in prose?

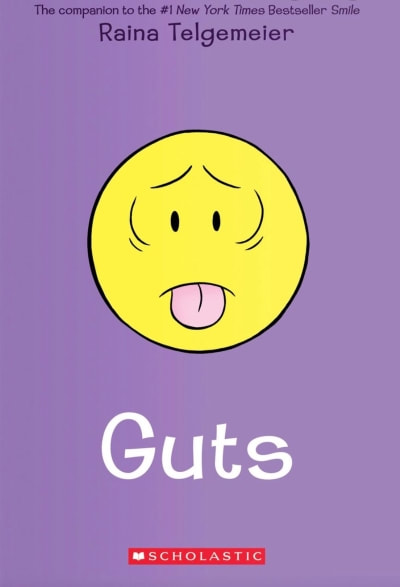

Guts. By Raina Telegemeier. Scholastic/Graphix. ISBN 978-0545852500 (softcover), $12.99. 224 pages. Raina Telgemeier is an engine, a star, a phenomenon. All of us who follow the world of graphic novels have heard this. For several years Telgemeier has borne a job description that, until recently, perhaps no one imagined we would ever need: America’s best-selling graphic novelist. Hype surrounds her like a halo (go, Raina!) Her success is proof of the graphic novel’s decisive new mainstreaming, and further proof, if any were needed, of the buying power and cultural clout of tweenage girls. She is, we’re told, “the Judy Blume of graphic novelists,” and her stardom has been a bellwether of the children’s graphic novel movement. Telgemeier’s publisher, Scholastic, has capitalized on all this with gusto, rolling out the red carpet for each new release and boosting Raina to million-copy print runs. Earlier this year, a spinoff product, Share Your Smile, a kind of “interactive journal,” signaled a new phase in the branding of Raina: an exhortation to her readers to write their own autobiographical stories in the vein of Telgemeier’s breakout books, Smile and Sisters. I honestly don’t know what to think of Share Your Smile, which seems more about design than revealing content: a guided activity book comparable to Wreck This Journal, The Diary of an Awesome Kid, and so many others. I suppose I had wanted to see something more reflective or essayistic, less about prompts and nearly-blank pages for readers to fill in. (It strikes me that young readers may get more from how-to cartooning books like James Sturm et al.’s Adventures in Cartooning or Ivan Brunetti’s Comics: Easy as ABC!) Telgemeier’s latest, though, Guts, now that’s a real book — and for me, her best. Guts is a middle-grade girlhood memoir akin to Smile and Sisters, and designed to match (Telgemeier’s autobiographical books and fictional books are distinguished by different design schemes). It’s in familiar Raina territory: a story of social awkwardness and anxiety, family and friendship, and the minute moral decisions and moments of confusion, defensiveness, and selfishness that can make school life so complicated. Predating the events of Smile, it depicts Raina, the author’s childhood self, going through fourth and fifth grade. Though it matches its sibling titles (indeed, Scholastic has just released all three in a boxed set), it stakes out its own thematic turf, revealing Raina’s anxieties and phobias in an emotionally charged way that goes a step further. It’s a brave book, and, I’m tempted to say, one that only a well-established children’s author could get away with. Guts depicts panic attacks and (as the title hints) upset stomach, cramping, and retching, as well as social and eating-related anxieties. It joins the considerable body of autobiographical comics that deal with anxiety, psychological distress, and neurodivergence. (Such themes are foundational to autographics as a genre, from Justin Green onward.) For a middle-grade graphic novel, Guts is, well, gutsy; it includes many scenes visualizing physical and psychological discomfort, and in some cases sharp pain and outright terror. It also includes quite a few scenes of bathrooming, bodily embarrassment, doctor’s office visits, and therapy sessions. “Treatment” is essential to its story. In short, Guts contributes to the graphic medicine movement. In the process, it yields the most harrowing and inventive pages Telgemeier has yet created. At the same time, Guts is very much a young reader’s book, never forgetting its main audience and taking care to explain and palliate the scary stuff—not with promises of quick cures and happy-ever-afters, but by showing that anxiety and panic are survivable and can be understood and, with practice, coped with and reduced. Young readers who dig Telgemeier’s books are likely to find Guts a warm, awkwardly funny, and ultimately reassuring guide. I tend to think that Telgemeier’s best books are her memoirs. Her fictional graphic novels to date, Drama and Ghosts, have been well-intentioned liberal fables with under-examined premises (Drama has been faulted for reproducing romantic stereotypes of the antebellum South, and Ghosts for naive cultural appropriation and whitewashing colonial history). Both have tried to do good things: Drama is a queer-positive, gender-defying romance, and Ghosts a story of family affected by illness and disability. But they aren’t tough-minded books, and Telgemeier doesn’t quite skirt the pitfalls built into their premises. In her memoirs, however, Telgemeier has crafted a believably human alter ego, just anxious and at times selfish enough to pose serious ethical dilemmas, and she has a way of disclosing certain hard things that don’t get solved, even as her boisterous cartooning conveys a bright, affirming outlook on life. The balance is exquisite, and Telgemeier usually nails it. Guts is the Raina book I’ve liked best. I will remember its formal gambits (startling for a middle-grade graphic novel) and its honesty. Telgemeier, at once a first-class storyteller and a commercial powerhouse, has clearly hit her stride. This book take chances, the chances pay off, and I’m impressed by the way she manages to walk the tightrope.

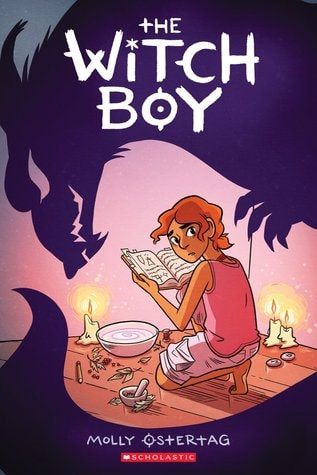

The Witch Boy. By Molly Knox Ostertag. Scholastic/Graphix, 2017. ISBN 978-1338089516. $12.99, 224 pages.I met Molly Knox Ostertag at the Chevalier’s event on March 15, and that inspired me to read, at last, The Witch Boy, a talked-about graphic novel from last fall and now a finalist for the Excellence in Graphic Literature Awards. So, in the spirit of catching up: Billed as a middle grade fantasy, The Witch Boy envisions a clan of witches and shapeshifters on the edges of human society who subscribe to a strictly gendered division of roles: witches are women, and shapeshifters men. However, protagonist Aster is a boy whose magic leans toward witchery, not shifting. This is taboo. Aster’s family anxiously clings to its binarism; his witching strikes them as uncanny and ill-starred. This tale of forbidden skills and aspirations is also, implicitly, a coming-out story; the plot inverts the familiar premise of a girl braving to enter what is deemed a man’s field while also queering notions of gender identity. Indeed the novel exposes the unease that a queer or gender-nonconforming child can bring to an insular community. Aster, shamed and fretted over by his kin, finds support in a non-magical girl named Charlie (Charlotte), a young athlete of color whose own resistance to gender norms is quickly sketched. Charlie, blunt and unaffected, frees Aster up a bit, and helps him use his forbidden gifts to resolve a mystery that is threatening the boys of his clan—a mystery that traces back to his family’s very history of shaming those who do not fit their gender norms. The novel hurtles to an end with an outpouring of backstory from a wise grandmother who holds the key, plot-wise, and the conclusion brings not perfect harmony ("Mom and Dad don't really get it...") but acceptance and the promise of further adventures (sequels!). The Witch Boy is a promising solo debut from Ostertag, already a busy cartoonist and co-creator of several comics. She wrote, drew, lettered, co-designed, and (with help) colored the book, and the story feels personal. The artwork, expressive and clear, recalls Hope Larson for me, but Ostertag is looser and uses backgrounds more sparsely. Her storytelling pulls me through effortlessly, though at times atmosphere and setting seem too thinly (or hurriedly) drawn for full effect. The ending is baldly telegraphed, and the last threescore pages rush to get there, with hasty exposition. But I enjoy the world, including its multiracial and queer-positive families, and the fact that the grownups in it, even at their most fearful or unbending, are not caricatures but strong folk anxious to do right. There is potential for a complex series here, and I look forward to more from Ostertag. Soon, I gather!

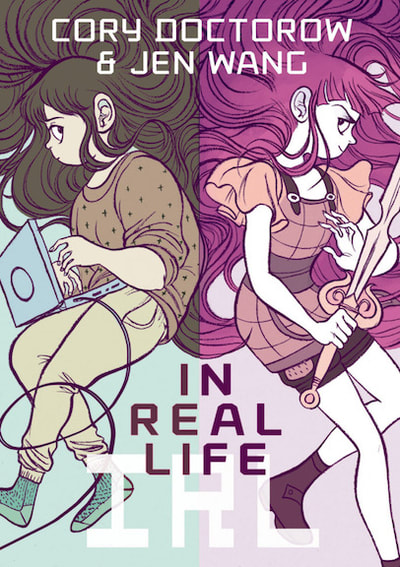

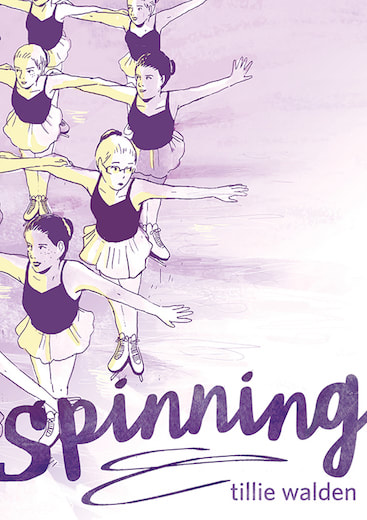

WOW. No sooner do I finish reviewing Jen Wang's splendid new graphic novel, The Prince and the Dressmaker, than I realize that Wang and a panel of other great talents will be discussing the book at Chevalier's Books, Los Angeles's fabled independent bookstore, tomorrow night, Thursday, March 15, at 7:00pm. The details are at Chevalier's site, here (Chevalier's is at 126 North Larchmont Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90004). Wang, author of Koko Be Good (2010), co-author, with Cory Doctorow, of In Real Life (2014), and co-founder of the Comic Arts LA festival, will be joined by Doctorow, as well as two other notable comics creators, Molly Knox Ostertag and Tillie Walden. Doctorow is of course a novelist (author of Little Brother among others), columnist, tech expert and activist, and the co-editor of Boing Boing. Ostertag is the author of the recent graphic novel The Witch Boy (whose exploration of gender resonates with The Prince and the Dressmaker), co-creator of the graphic novel Shattered Warrior, and co-creator of the ongoing webcomic Strong Female Protagonist. Walden is author of the recent graphic memoir Spinning (one of 2017's most acclaimed comics) and the webcomic (soon to be graphic novel) On a Sunbeam, as well as the graphic books The End of Summer, I Love This Part, and A City Inside. This is an incredible gathering of talent. Frankly, it would be hard to imagine a stronger panel than this when it comes to the intersection of children's publishing and graphic novels, small-press and independent comics, women comics creators, and explorations of gender and sexuality in comics. I dearly hope to make this event, which I expect is going to be great!

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed