|

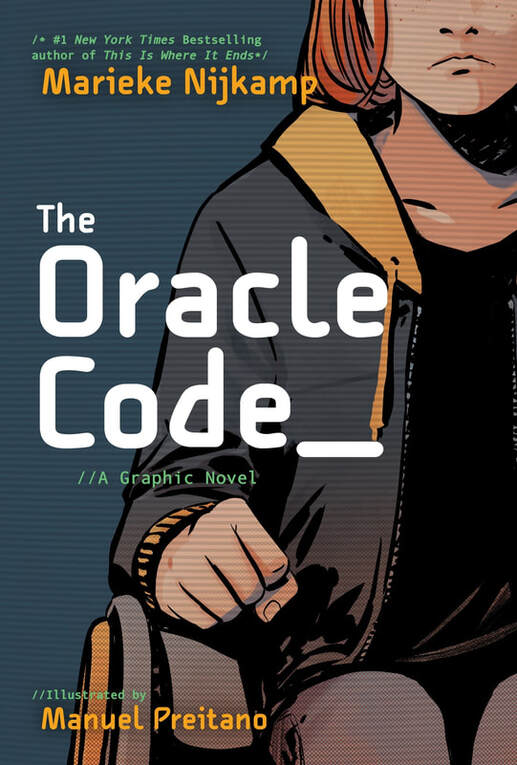

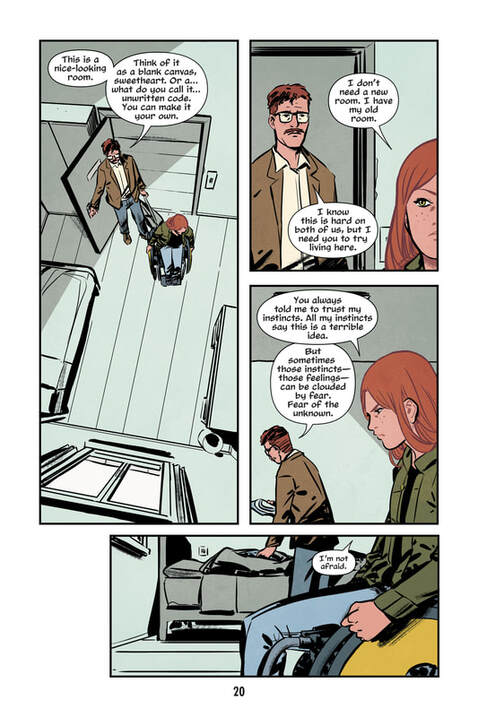

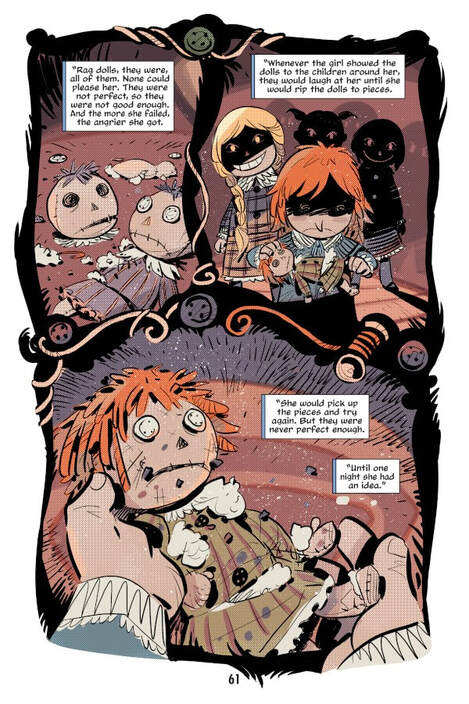

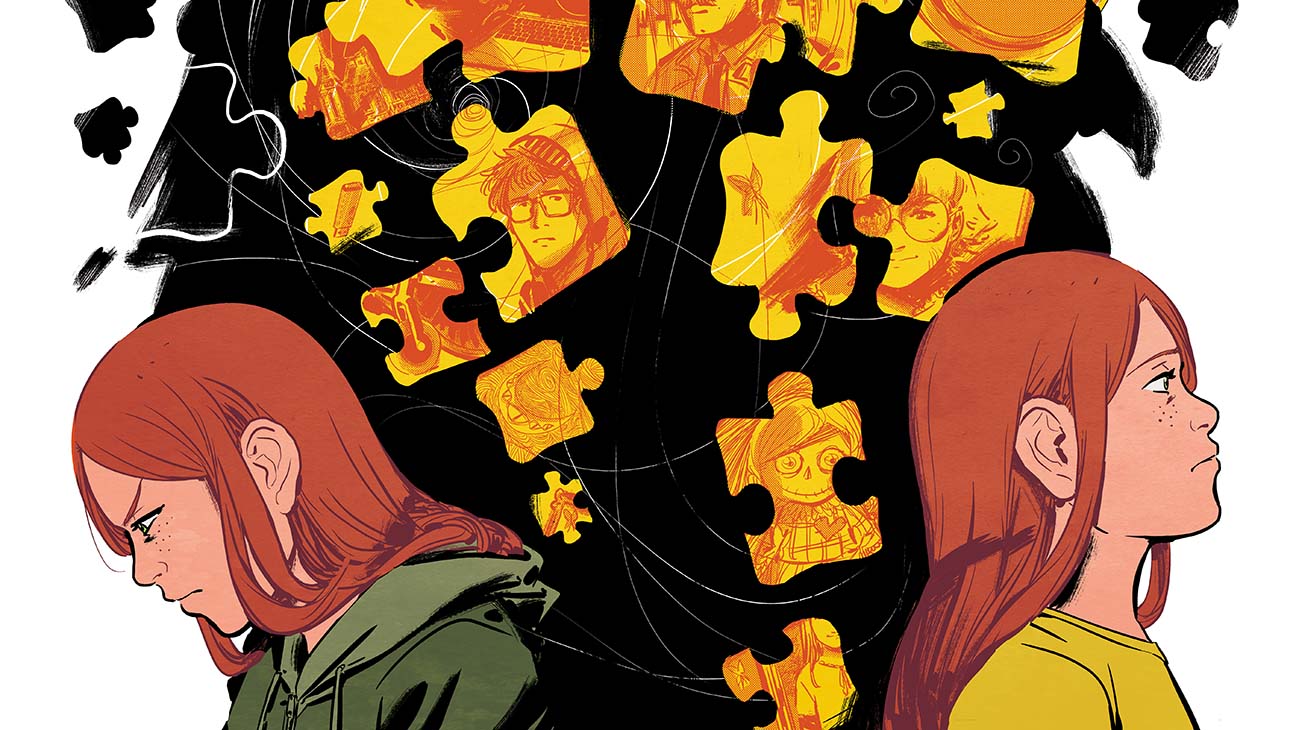

The Oracle Code. Written by Marieke Nijkamp; illustrated by Manuel Preitano; colored by Jordie Bellaire with Preitano; lettered by Clayton Cowles. DC Comics, ISBN 978-1401290665 (softcover), 208 pages. US$16.99. March 2020. (This is the second in an occasional series reviewing children’s and Young Adult graphic novels from DC. See the first here.) Paralyzed by a gunshot wound, brilliant young hacker Barbara Gordon (daughter of Gotham’s police commissioner) undergoes rehabilitation at the so-called Arkham Center for Independence — which, surprise, turns out to be a sinister place, a haunted house even, from which patients keep disappearing. Though traumatized, and at first resentful and alienated, Barbara gradually bonds with other patients, and together they form a team to unravel Arkham’s dark secret. This DC graphic novel does not appear to mesh with any version of DC continuity, and its Barbara Gordon differs sharply from previous Barbaras (Batgirl or Oracle). In fact, its DC-ness is nominal, and could be erased with a few minor edits. It’s not a superhero story in the usual sense. Rather, it’s a Young Adult thriller that follows many of that genre’s conventions: young people up against corrupt adult institutions, fighting with official powers, fighting for self-definition, testing their mettle with no outside help. It’s also grounded in an intersectional and community-oriented disability politics that makes it stand out among DC books. Writer Marieke Nijkamp is an acclaimed author of YA thrillers (e.g., This Is Where It Ends), editor of a disability-themed YA anthology (Unbroken), and advocate for greater diversity in children’s and Young Adult publishing (she served as a founding officer of We Need Diverse Books). The Oracle Code’s plot seems to have been informed by her experience living in a medical rehabilitation facility as a teenager. Her loner hero, Barbara, eventually enters into community, and, with her team, emphatically rejects the idea of being “fixed” (echoing Nijkamp’s criticisms of the trope of curing disability). The book’s politics are obvious and central, and some minor characters and relationships seem designed to make points — or to serve merely as hurdles to Barbara’s ferocious drive. The plot, I think, rushes to a too-sudden conclusion; I can see the story’s somewhat familiar shape from far off. Barbara herself, though, is a distinct character, and the book gives her time and space to be properly angry. If the book preaches, it doesn’t preach to Barbara. Also, the wrap-up wisely lets certain resolutions stay ambiguous; this is no facile overcoming narrative in which all things are made better. The book reflects on the healing value of dark stories — through a series of unsettling embedded tales, like bedtime stories — and itself does not shy away from trouble. The Oracle Code, in sum, is a designedly Young Adult novel that reflects and capitalizes on the disability politics always implicit in the Oracle character. Visually, The Oracle Code wavers between arid daytime plainness — perfect for a medical facility — and darkly atmospheric nighttime scenes. Illustrator Manuel Preitano favors a naturalism that, for me, recalls the post-Mazzucchelli work of David Aja (though without Aja’s drastic stylization and formalist invention). The intentionally limited color palette (colors are credited to both Jordie Bellaire and Preitano) pits vivid yellow-orange and nocturnal purple-blue against drab olive and icky, hospital-bland greens. Insipid, textureless rooms — like the flat, medicalized interiors we all know, presumably lit by fluorescents — clash with densely shadowed scenes defined by slashing swathes of black and vigorous dry-brush technique. Bright jigsaw puzzle pieces stand out against the general gloom and serve as a braided visual device: a multivalent symbol that variously signifies trauma, fragmentation, reassembly, accomplishment, and, of course, mystery-solving. The layouts are dynamic, shifting, yet steadily rectilinear, except for the embedded “bedtime” stories, which boast curving, swirling panel shapes and a contrasting, cartoonish style. This novel is, as far as I know, Preitano’s longest sustained work for the US market (he has also worked on the series Destiny, NY and several comics for Zenescope), and departs from the sometimes lurid retro aesthetic of his illustrations for the Vaporteppa fiction line, in his native Italy. This looks like a big step forward for the artist. On balance, The Oracle Code shows the potential of YA fiction that happens to be set in DC’s story-world. It’s more self-contained, and more attuned to the conventions of YA fiction, than I had expected. To me, these are good things. One thing gets to me, though: despite the signs that this book is a rather personal work for Nijkamp, it is copyrighted solely in the name of DC Comics — that is, it’s work for hire (though it bears about as much resemblance to prior Oracle stories as, say, Neil Gaiman and company’s Sandman bore to prior Sandmen). I think that’s a shame, and, honestly, this is one reason I have not been able to muster great enthusiasm for DC’s work with YA and children’s authors. As long as DC graphic novels are centered on company IP and the creators are wholly dispossessed of any equity in the work, as long as DC persists in these damaging comic book industry practices, the promise of its young readers’ line will be dampened. The Oracle Code is very unusual for a DC comic — its focus on a non-superpowered community of young women, and willingness to highlight a young woman’s anger and power, are laudable — but it’s still shackled to DC’s old way of doing things.

0 Comments

Due to the pandemic, San Diego's Comic-Con International has become a virtual event, taking place this week. It started yesterday, Wednesday, July 22, and continues through this Sunday, July 26. This is Comic-Con@Home. Of greatest interest to me are the virtual "panels" spread over the five days of the event (reportedly more than 350 panels in all). These run the usual gamut of pop culture topics, some comics-focused, some not. Regrettably, the panels are entirely prerecorded, which means no live audience interaction, no Q&A. Most will be in the nature of recorded Zoom calls. This bums me out, but is better than nothing — and there are some very promising-sounding panels on offer. Below, divided by day, are panels that catch my eye or may be of particular interest to KinderComics readers. Note that not all of these panels focus on children's or young adult comics or on education. Some focus on other fannish interests of mine, or on particular creators of note. This is a glimpse into my mind! Obviously, Comic-Con@Home is already well underway; this post comes late. But many if not all of the panels listed below will be available to view online once this week is over. (CCI says that most of its panels "will also be available AFTER the July 22-26 dates, although there are some that may have a limited time period attached to them.") The panels can be accessed via CCI's online program or their YouTube channel. They can't be accessed before their official start times, but once they're up, they're up. There could be weeks and weeks of good viewing here! July 22, WednesdayThis first day continues the now-familiar Comics Conference for Educators and Librarians (CCEL), a Wednesday-afternoon tradition since 2016, co-sponsored by Comic-Con and the San Diego Public Library since 2016. All of Wednesday’s seventeen panels, AFAIK, are CCEL-branded, and all are aimed at librarians and/or teachers. Below are the Wednesday panels that really stood out to me; for info on all of the CCEL panels, follow the CCEL link above to the SD Public Library's page: Teaching and Learning with Comics 3:00pm – 4:00pm With Peter Carlson, Antero Garcia, and Susan Kirtley, co-editors of the anthology With Great Power Comes Great Pedagogy, and creator-teachers Nick Sousanis, Ebony Flowers, and David F. Walker and Brian Michael Bendis. (I’ve already watched this one, and it was terrific!) Comics in the Classroom Ask Me Anything: Pick the Brains of Teachers, Administrators, Creators, and Publishers 3:00pm – 4:00pm The Power of Teamwork in Kids Comics 5:00pm – 6:00pm Including Gene Luen Yang, Chad Sell, Jim Ottaviani and Maris Wicks, and moderator Betsy Gomez. New Kids Comics from Eisner Award Publishers 5:00pm – 6:00pm Including Jerry Craft, Faith Erin Hicks, Robin Ha, Derick Brooks, Jonathan Hill, and moderator Candice Mack Words and Pictures Working Together: Strategies for Analyzing Graphic Texts 6:00pm – 7:00pm Comic-Con Celebrates Fifteen Years of Eisner Librarians 6:00pm – 7:00pm Including librarians and former Eisner Award judges Kat Kan, Karen Green, Jason Poole, Dawn Rutherford, Traci Glass, and moderator John Shableski. July 23, ThursdayGraphix: Get Drawn In 11:00am – 12:00pm Batgirls! 12:00pm – 1:00pm Comics During Clampdown: Creativity in the Time of COVID 12:00pm – 1:00pm 75th Anniversary of Moomin appreciation 1:00pm – 2:00pm Comics Satire and The New Political Cartoon 2:00pm – 3:00pm The Brave New World of TwoMorrows 2:00pm – 3:00pm Comic-Con Museum: A Museum for All Ages 3:00pm – 4:00pm Teaching and Making Comics 6:00pm – 7:00pm Including Ebony Flowers, Roman Muradov, Trina Robbins, Sophie Yanow, and moderator James Sturm. July 24, FridayHoward Cruse: The Godfather of Queer Comics 10:00am – 11:00am Absolutely not to be missed IMO. Last Gasp: 50 Years of Publishing the Underground, Part I 10:00am – 11:00am Reclaiming Indigenous History and Culture Through Comics 11:00am – 12:00pm Decoding the Kirby/Lee Dynamic 11:00am – 12:00pm Raina and Robin in Conversation (starring Raina Telgemeier and Robin Ha) 11:00am – 12:00pm TragiComics 12:00pm – 1:00pm History Goes Graphic 12:00pm – 1:00pm Harryhausen100: Into the Ray Harryhausen Archive 1:00pm – 2:00pm Water, Earth, Fire, Air: Continuing the Avatar Legacy 3:00pm – 4:00pm The Annual Jack Kirby Tribute Panel 4:00pm – 5:00pm VIZ: A Haunting Conversation with Junji Ito 6:00pm – 7:00pm 32nd Annual Will Eisner Comic Industry Awards 7:00-8:00pm Another must for me! July 25, SaturdayLast Gasp: 50 Years of Publishing the Underground, Part II 10:00am – 11:00am The Guide: Overstreet's 50th Anniversary 10:00am – 11:00am Warner Archive's Secret Origins of Saturday Morning Cartoons 11:00am – 12:00pm Inspired: Personal Stories in Graphic Novels 12:00pm – 1:00pm Diversity and Comics: Why Inclusion and Visibility Matter 12:00pm – 1:00pm Personal, Political, Fictional, and Factual 1:00pm – 2:00pm Latinx & Native American Storytellers 1:00pm – 2:00pm Tribute to Dennis O'Neil: Beyond Batman 2:00pm – 3:00pm Gender, Race, and Comic Book Coloring 2:00pm – 3:00pm Mexico's Magnificent Stop-Motion Seven 3:00pm – 4:00pm Best and Worst Manga of 2020 4:00pm – 5:00pm 20 Years of DeviantArt: An Oral History 4:00pm – 5:00pm Adrian Tomine spotlight panel 5:00pm – 6:00pm Comic Shops : Persevering through Crisis 5:00pm – 6:00pm Mexican Lucha Libre: History, Tradition, Legacy 6:00pm – 7:00pm Fantagraphics and IDW: Classic Comics Reprints 6:00pm – 7:00pm Out in Comics 33: Virtually Yours 6:00pm – 7:00pm July 26, SundayBOOM! Studios: Discover Yours

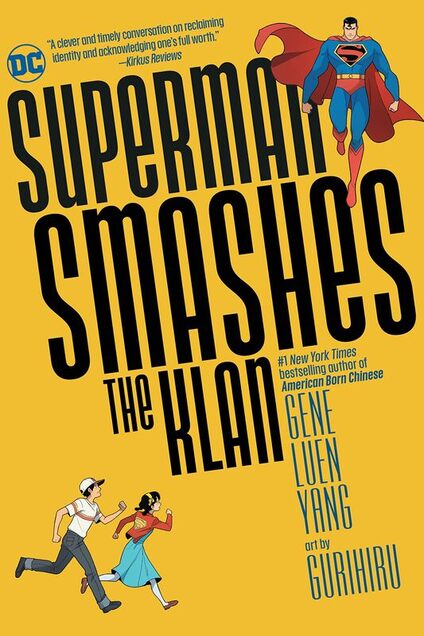

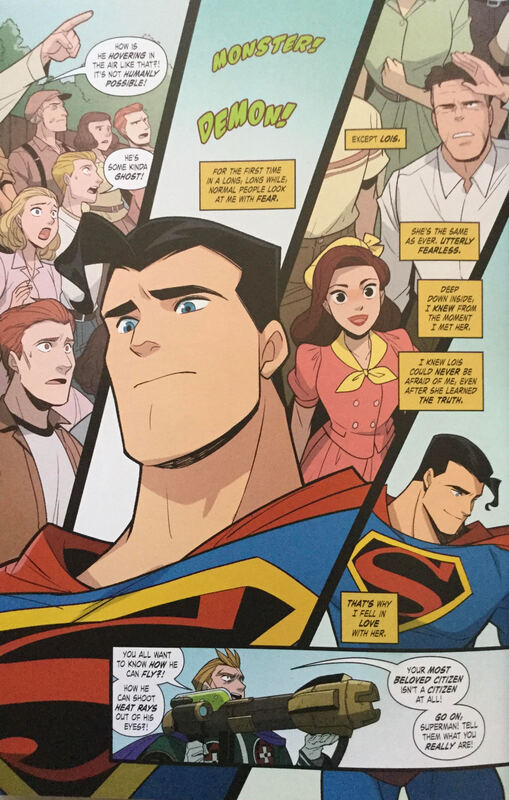

11:00am – 12:00pm Jack Kirby 101: An Introduction 12:00pm – 1:00pm Masters of Style: Woodring, Fleener, Muradov and Hernandez 1:00pm – 2:00pm Comics about Motherhood and Reproductive Choice Including Lisa Wool-rim Sjoblom, Leslie Stein, Teresa Wong, and moderator Hillary Chute. 2:00pm – 3:00pm Another must! Inspired by Real Life: The True Stories Behind Graphic Novels 2:00pm – 3:00pm LGBTQ Comics and Popular Media for Young People 2:00pm - 3:00pm Superman Smashes the Klan. By Gene Luen Yang and Gurihiru. Lettering by Janice Chiang. DC Comics, ISBN 978-1779504210 (softcover), May 2020. US$16.99. 240 pages. (The first in an occasional series reviewing children’s and Young Adult graphic novels from DC.) One of the pleasures of reading Gene Luen Yang is watching him play — and take risks — with sources. American Born Chinese gives the Chinese literary classic Journey to the West an Americanized (and Christianized) spin, while riffing on sitcoms, Transformer-style mecha, and Yang’s own boyhood as an immigrant’s son. The recent Dragon Hoops (reviewed here in March) folds the history of basketball, reverently sourced, into its account of Yang’s last year as a high school teacher. Yang’s five-volume run on Avatar: The Last Airbender (2012-2017), his first collaboration with Japanese art team Gurihiru (Chifuyu Sasaki and Naoko Kawano), is a sequel to the beloved TV series (2005-2008). The Shadow Hero, Yang’s 2014 graphic novel with artist Sonny Liew, revives an obscure Golden Age superhero, Chu Hing’s Green Turtle (1944-1945), giving him a new origin and feel. Yang’s latest, Superman Smashes the Klan (now gathered into one volume, after a three-issue serial release last year), draws from an antiracist storyline in the Adventures of Superman radio serial in 1946, but adapts it freely. Superman Smashes the Klan interweaves several threads from Yang’s previous work. Once again, he plays with DC Comics and Superman lore; again, he collaborates with Gurihiru. Once more, as in The Shadow Hero, he treats the superhero-with-secret-identity as an overt assimilation fantasy, in a period American setting. It’s the best of his DC projects by a long shot: the most obviously personal, the most graphically whole, consistent, and readable. It’s also, I think not coincidentally, the one that comes closest to the children’s and YA graphic novel genre that Yang is best known for. This is one of the more interesting of the many 21st-century reinterpretations of Superman’s origin. It happens that my wife and I have been reading it at the same time as another reinterpretation, Tom De Haven’s prose novel It’s Superman! (2005). De Haven’s is a free retelling of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster’s original, late mid-1930s Superman, done up as nerdy, name-dropping historical fiction in the vein of Michael Chabon’s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay (2000). It’s Superman! digs hard into that vein, stressing economic misery, political unrest, migration, segregation, and pervasive everyday racism in tune with its Depression-era setting. Also, it’s peppered with cameos by real-world people, neighborhoods, architecture — you name it, De Haven has researched it. Add in sexual knowingness, lurid violence, and odd character studies of crooks and victims, and you’ve got a very “adult” riff on the Siegel and Shuster model, something not too far from De Haven’s other comics-themed historical novels. Don’t get me wrong: It’s Superman! is a terrific book, one I’d like to teach when I get around to doing an all-Superman course. I think it would teach well alongside Superman Smashes the Klan, as both replay Superman’s origin in early 20th-century period (the mid-30s for De Haven; 1946 for this book) — and both stress Clark Kent’s moral education, his growing awareness of social injustice. Yet the two books are quite different. De Haven’s Clark never finds out where he came from; though he suspects that he is not from Earth, he never learns about planet Krypton. The book only hints at Clark’s origins. De Haven works hard to suggest how this lonely, alienated young man might turn to reporting, and to his unrequited love for Lois Lane, as a way of becoming “just like everybody else.” Yang and Gurihiru’s Clark, on the other hand, learns more about his extraterrestrial origins — there’s more SF in his story. He too, though, longs to be like everyone else, to assimilate — so much so that he hides his light under a bushel, downplaying or even failing to recognize some of his powers. He befriends young Roberta and Tommy Lee, children of a Chinese immigrant family that has just moved to Metropolis, and combats a militant, White supremacist Klan group that terrorizes them. At the same time, he must confront his fears of revealing his own alienness, and frightful visions of himself and his birth parents as green-skinned monsters. This Clark starts out not knowing about Krypton, but gradually learns of it (through a familiar plot device: a bit of leftover Kryptonian tech). In the course of fighting the Klan, Clark discovers the full extent of his powers, hidden from him by his own desires to assimilate: a clever way to explain how the running and jumping Superman of early Siegel and Shuster became the flying Superman with X-ray vision that we know now. But much of the story belongs to young Roberta (Lan-Shin) Lee, whose worries about fitting in mirror Clark’s, and whose empathy with him proves key to unlocking his potential. Yang and Gurihiru give us brief flashbacks to Clark’s origin, while focusing on his anxious way of passing among humans in the present — an anxiety Roberta knows all too well. The book's nonlinear retelling deftly frames the old origin story as a fable of assimilation (à la The Shadow Hero). Roberta and Clark, both immigrants uncomfortably aware of their alienness, together foil the Klan and stand up for a vision of Metropolis — implicitly of America — in which everyone is “bound together,” sharing the same future, “the same tomorrow.” In this way, Superman Smashes the Klan makes its antiracist parable integral to Superman’s own process of becoming. Superman Smashes the Klan is not subtle; after all, it’s a value-laden fantasy of nation, like so many American superhero comics — and it obviously courts a young audience (Young Adults, says the back cover, but I’d say middle-grade). The book wears its values on its sleeve. Also, the period setting seems idealized: for example, Inspector Henderson of the Metropolis PD is here portrayed as African American, which tends to suggest a very progressive Metropolis for 1946, one in which the Klansmen’s anti-Black racism makes them outliers. This may be too easy. Though the story acknowledges that racism takes many forms, the masked Klansmen provide an obvious, simplistic focus (I’d expect a YA novel about racism to be more ambiguous and challenging on this score). On the other hand, the book allows some of its racist characters to grow: young Chuck, nephew of the Klan’s leader, learns to reject his uncle’s ways at the boffo climax — at which a bunch of kids help Superman save the day, own his identity, and face down xenophobia. Superman Smashes the Klan, then, dares to hope — as children’s texts so often do — that the openness and innocence of the young can redeem a society riven by bigotry and corruption. This utopian vision is familiar to anyone who studies children's literature; it's obvious. Yet, obvious or not, this is just the kind of Superman story I prefer to read, one in which Supes clearly stands for a decent, humane, inclusive ideal. It’s on the nose, sure, but that doesn’t bother me much. It could make a terrific animated film, in post-Spider-Verse mode (we can only hope). That said, Superman Smashes the Klan is not as effective, I think, as Yang and Liew’s Shadow Hero, which more daringly uses superhero tropes to create a layered, ambivalent assimilation story. This is a Superman comic, after all, hence constrained; the nervy, potentially offensive gambits in The Shadow Hero are not to be expected. Yet Yang has taken some interesting risks in reworking Superman’s origin; it’s good to see the truism that Superman is an immigrant being put to real use. It’s likewise good to see Superman sprung free — liberated — from the suffocating weight of “DC Universe” continuity. I'm a little sad that this has to happen in a distanced period setting, rather than a contemporary one. (I'd love to see this book spawn a series of timely, obviously relevant Superman GNs set in the present day, for the same audience.) Stylistically, I’ll say that I find the book a bit too clean and antiseptic to conjure the desired sense of period; Gurihiru’s neat, smart artwork strikes me as too textureless and bland to evoke a mid-1940s Metropolis. I’d have liked to see a grittier city setting, with more grimy particulars, so that Superman’s bright, heroic doings would stand out by contrast. On the other hand, Gurihiru’s pages are dynamic, inventive, and ever-readable. The book combines the snazziness and roughhousing energy of most superhero comics with clear-line legibility. It’s fetching and fun to look at, and Yang and Gurihiru are clearly sympatico (their Avatar collaboration obviously prepared them for this). If only most DC comics were this free and confident of their aims. The recent news that Marvel is teaming up with Scholastic — that is, licensing Scholastic to produce a series of original graphic novels for young readers starring Marvel heroes, to be published under the Graphix line — gives me hope that we may see a flood of comics with similar aims. That announcement came as a surprise, but perhaps it shouldn't have: after all, young readers' graphic novels are the thriving sector in US comics publishing today. Maybe, just maybe, US-style superhero comics, not just movies, TV shows, and goods based on such comics, can once again become popular, widely available children's entertainment. Having lived through (and, for a time, invested emotionally in) the revisionist adultification of superheroes in the 1980s to 90s, I find this prospect oddly exhilarating. I wonder what Yang thinks — and if he is keen to do more books of this type. Man, what I wouldn’t give to teach a sequence like so: Siegel and Shuster’s first two years of Superman (1938-1940), De Haven’s retake, The Shadow Hero, and Superman Smashes the Klan. I bet that would kick off some great conversations. PS. Gene Luen Yang has been on the board of the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund since 2018. In light of the infuriating recent news out of that troubled organization, his frank and reflective remarks on Twitter have been illuminating. Yang — wisely, I think — values the Fund's mission over the current organization, while also pointing out the good work done by current CBLDF staffers. It's quite a tightrope walk — and recommended reading for those who've been following the news of the CBLDF, and the comic book field's larger sexual harassment and abuse crisis, on this blog. PPS. Gene Yang is slated to take part in three virtual panels at this week's Comic-Con@Home: The Power of Teamwork in Kids Comics (today, Wednesday, July 22); Comics during Clampdown: Creativity in the Time of COVID (Thursday, July 23); and Water, Earth, Fire, Air: Continuing the Avatar Legacy (Friday, July 24). These events, like most panels making up Comic-Con@Home, will presumably be prerecorded, hence without live audience Q&A, which is a shame. But, still, there should be some interesting back-and-forth among the panelists, and Yang is a great ambassador and thinker on the fly. See comic-con.org or Comic-Con's YouTube channel for further info.

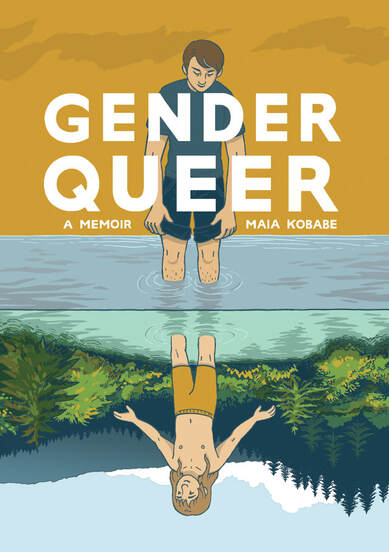

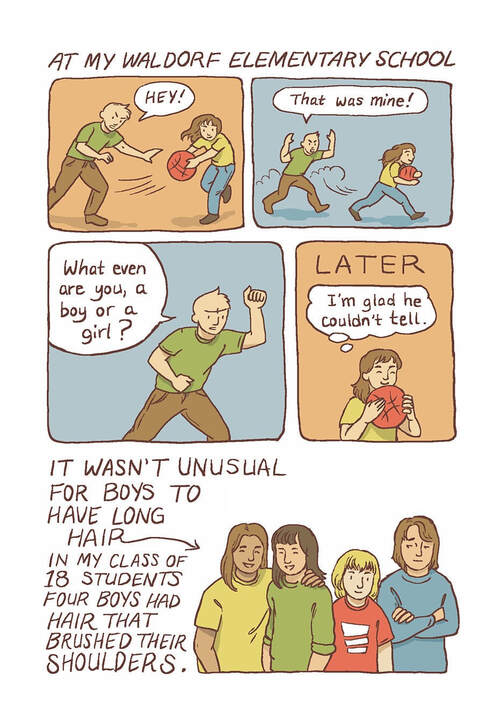

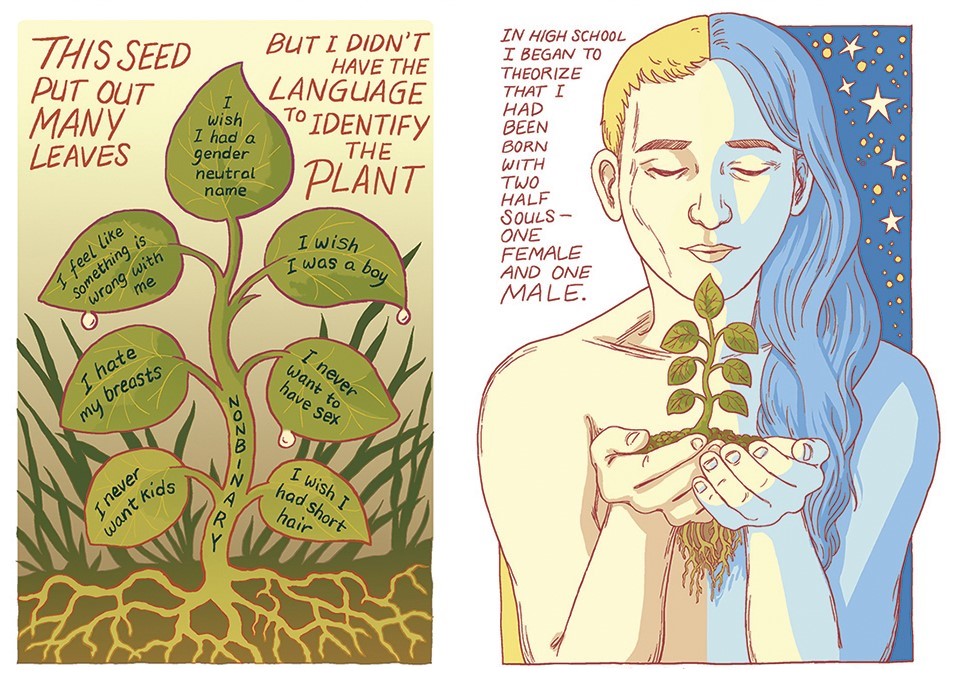

Gender Queer. By Maia Kobabe. Colors by Phoebe Kobabe. Sensitivity read by Melanie Gillman. Oni Press, ISBN 978-1549304002 (softcover), May 2019. $17.99. 240 pages. Glad to get to this one, at last. Gender Queer bills itself (on its cover) as both a memoir and a guide. It does both well. As a memoir, it is intimate, recounting a personal story about the push-pull of body and mind, self and society. It is as candid as it must be, as discreet as it can be. This is Maia Kobabe’s story, told with autographic frankness. As a guide, it gestures beyond the personal, giving an authoritative (though not universalizing) perspective on gender dysphoria, asexuality, and the politics of being a nonbinary subject in a binary culture. Actually, it works well as a guide because it works as a story — meaning Gender Queer is authoritative because Kobabe lived it. The book demonstrates how comics, by interweaving picture, word, and symbol, can evoke the general through the particular; how graphic memoir can do the work of political as well as autobiographical witness. Gender Queer credibly witnesses to tough issues precisely because Kobabe does not assume that anyone else has lived with those issues in precisely the same way; that is, the book honors the specificities of eir life (Kobabe uses the Spivak pronouns e, eir, and em). The quirks of eir own experience make the book what it is—yet sharing those quirks brings a vivid honesty that will speak to readers whose circumstances are very different from the author’s. Gender Queer is bookended by scenes of teaching and learning. In the opening, Maia struggles with eir autobiographical cartooning class, taught by MariNaomi (part of eir Comics MFA at the California College of the Arts); e resists the idea of sharing eir “secrets” on the page. Overcoming that resistance is prerequisite to the very book we are reading, and Kobabe depicts eirself tearing away a kind of veil to share eir story with us. In the closing, Maia teaches eir own comics workshop to tweens and teens at a local library, but struggles again: e reproaches eirself for not coming out to eir students, that is, not sharing eir nonbinary identity and preferred pronouns. Oddly, then, this coming-out story ends with an instance of not coming out, and of self-blame. The book is open about troubles and misgivings of this sort, as well as the familial and social awkwardness of negotiating new pronouns. In one striking scene, Maia’s aunt, a lesbian and committed feminist, responds to the pronoun question by challenging Maia’s perspective on FTM transitioning and genderqueerness, suggesting that these things may stem from misogyny, from a “deeply internalized hatred of women” (195). Maia is troubled by this challenge, of course, but the scene plays out with a delicate touch (eir aunt is properly supportive, not an adversary). Thus Kobabe is able to field a sensitive question, perhaps even to defuse the likely skepticism of some readers. I confess that these admissions of awkwardness and trouble swayed me; it was good to see Kobabe dealing with the struggles of family and friends without rancor or caricature. Gender Queer is that kind of book: humanly complicated, and willing to lean into complexity and trouble (it pairs well with L. Nichols’s Flocks in that regard). As an autographic, testimonial comic, Gender Queer adds to the fund of helpful cultural resources available to queer and gender-nonconforming young people. At the same time, it testifies to how Kobabe has drawn upon cultural resources in eir own journey: books, comics, Waldorf schooling, homeschooling, and art teachers (two depicted here, MariNaomi and Melanie Gillman, are queer cartoonists themselves). In Maia’s quest for self-understanding, books loom large: e is a voracious and self-documenting reader, a lister of books read and re-read. Kobabe’s account suggests that storytellers such as Neil Gaiman, Tamora Pierce, and Clamp served eir as resources for self-fashioning. A now-poignant passage recounts how Maia, a delayed reader at age eleven, taught eirself to read so as to devour the Harry Potter books (the irony of which, at the present moment, cuts like a knife). At a key moment late in Gender Queer, Kobabe turns to another book, neurophilosopher Patricia Churchland’s Touching a Nerve: The Self as Brain (2013), and even conjures Churchland as a character, an expert witness whose testimony about “the masculinizing of the brain” affirms Maia’s sense that “I was born this way.” This flourish is perhaps a touch too triumphant: Kobabe gives no sense of the intellectual debate around Churchland’s ideas, but simply invokes her as a bookish authority and solution. In any case, Gender Queer is, through and through, the record of a reader’s life. Style-wise, Gender Queer favors spareness and economy. Scenic backgrounds are few, and deliberate; Kobabe’s panels often consist of head shots against color fields. Conversation, reflection, and expression are everything. Pages typically follow a grid, whether unvarying or, more often, a bit relaxed, letting the white of the page show through: On the other hand, Kobabe lets rapturous, full-page drawing take over every so often. Clearly, eir minimalism is a considered choice, as confirmed by certain passages that break with the general sparseness. Dig for example these two facing pages: Though Gender Queer is discursive and text-filled, it never feels clotted. Kobabe’s organic hand-lettering and use of unbordered elements give the art breathing room. The pages include telling pauses, open bleeds, and dialogic exchanges that add up to a accessible, even brisk, read. Disarming is a good word for Gender Queer: the book’s honesty about dysphoria and bodily phobias may trouble some readers. I myself started the book in, admittedly, a guarded or hard-hearted mood, skeptical of the family ethos depicted: the utopian, back-to-the-woods values, the homeschooling, every little thing that I could interpret as a sign of sheltering or self-indulgence. Of course I was being pigheaded, and wrong — as the book’s warmth and complexity so clearly showed me. Gender Queer is moving and informative, an invaluable memoir and guide.

Further reporting by Michael Dean for The Comics Journal reveals a long history of administrative neglect, failed oversight, and abusive workplace practices at the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund. In particular, the testimony of former CBLDF Development Manager Cheyenne (Shy) Allott reveals a pattern of harassment by now-departed Executive Director Charles Brownstein back in 2010, and other disturbing details have come to light, including Brownstein's arrest for drunk and disorderly conduct (2003) and Brownstein's harassment of sometime CBLDF Deputy Director Mike Scigliano (circa 2008-2009). Allott's testimony, reported in detail by Dean, has only now become public, due to a binding non-disclosure agreement she was strong-armed into signing when she left her job at the Fund. The CBLDF has released Allott from that agreement. Current CBLDF Board President Christina Merkler officially responds to some pointed questions from The Comics Journal here. I want to support the CBLDF, and take some comfort from Merkler's promise of "a top-to-bottom rebuilding of Fund management, which includes modernizing our Board governance and communicating in a transparent style more representative of the people working for the Fund." Further, she has declared: We must better understand and explain why the Fund did or did not support previous causes important to our members, update our choices of imagery used in our publications and add deeper pre-hire background checks for prospective employees of the Fund. Finally, there will be a new infusion of Board members that reflects all that comics have to offer, with more representatives of our constituents, particularly creators and retailers. All that sounds promising. But the history of breach of trust here is profound. The Fund needs to shed daylight on every aspect of its workings. For too long, it has run on a shoestring, with an Executive Director unaccountable to anyone, a dispersed, out-of-touch Board that has let things slide, and a lack of due process in its own ranks. I have lost faith in the organization and hope for serious change. Frankly, this issue has gotten me all tangled up. I consider myself a free-speech liberal, for whom the protection of freedom of speech is key. To me, freedom of expression is the fountainhead from which other freedoms flow. So I believe in the mission of the CBLDF. It's disheartening to see what strikes me as a spirit of illiberalism growing among progressives who consider First Amendment activism to be simply a marker of privilege, or at odds with the fight for social justice. I tend to think that such critics value freedom of expression too lightly. Yet it is hard to argue with them when institutions like the CBLDF operate in shadows, neglectfully, unjustly, and jeopardize, through their inaction or complicity in wrongdoing, the very cause they are supposed to be fighting for. The CBLDF must align its First Amendment mission with a broader fight for civil rights and social justice. UPDATE, JULY 12: Over at The Daily Beast, Asher Elbein provides a thoughtful, tenaciously argued overview of the US comics industry's sexual harassment and abuse crisis, pointing out that "sexual harassment is a labor rights issue" and placing the crisis in the context of the industry's long history of abusive practices. Elbein's perspective usefully counters the misleadingly upbeat metaphor of weeding out a few "bad apples" from the industry; he shows how the system has been rotten in so many ways from the start, and requires systemic change. Recommended reading.

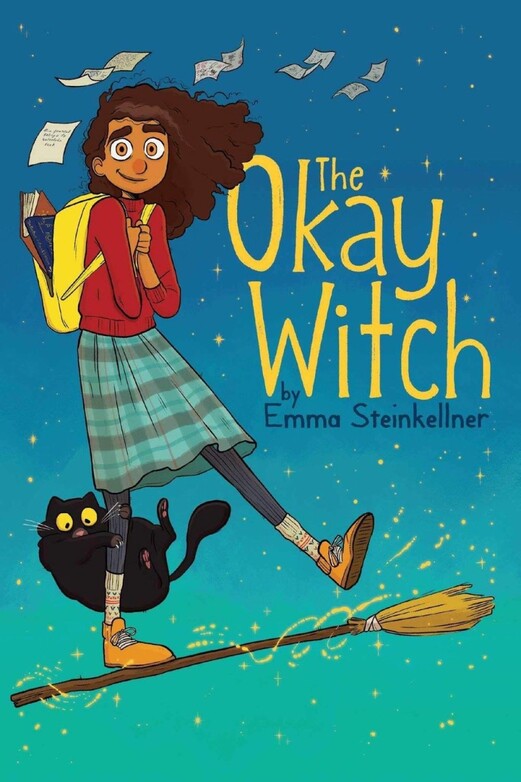

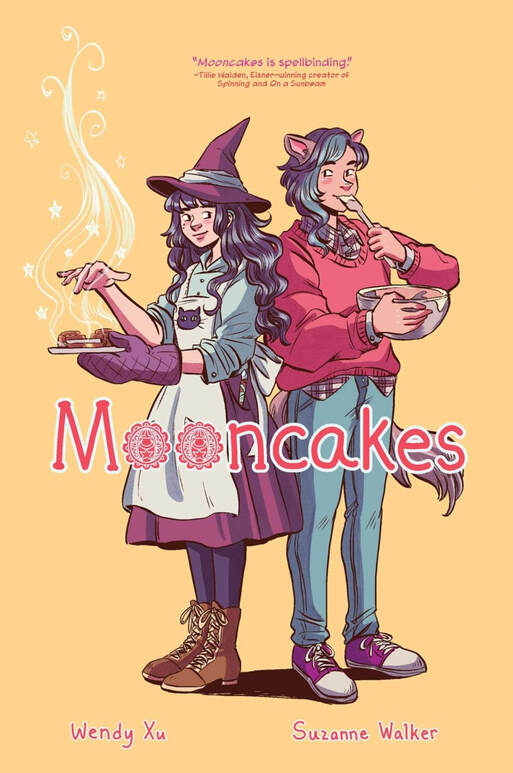

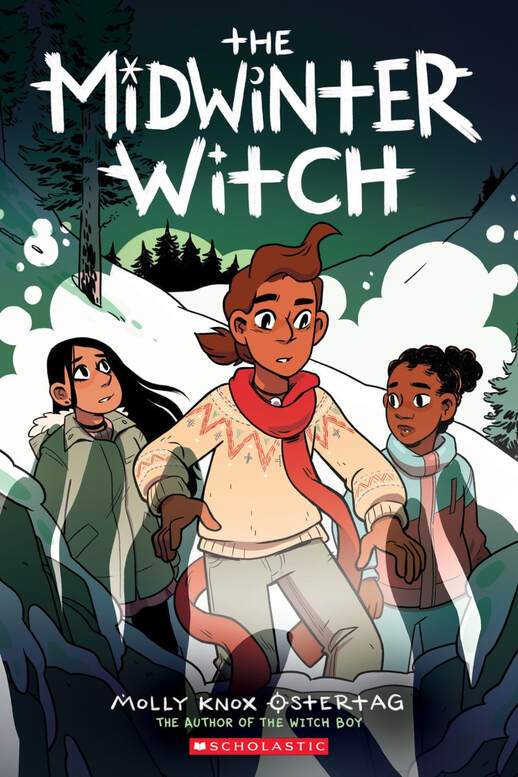

Coming-of-age stories about young witches have definitely become a genre in young readers’ graphic novels: a means of blending fantasy and Bildungsroman, and of telling stories about gender and sexuality, sometimes about other forms of difference, and about resistance versus conformism. Generally, these witch stories offer gender-conscious, often queer-positive, fables of identity. Post-Harry Potter, but often rejecting the Potter novels’ emphasis on passing in the mundane world, they also seem influenced by Hayao Miyazaki and the magical girl franchises of anime and manga. Here are reviews of three graphic novels about witches that came out, one after another, last fall: The Okay Witch. By Emma Steinkeller. Aladdin/Simon & Schuster, ISBN 978-1534431454 (softcover), Sept. 2019. 272 pages, $12.99. A girl named Moth, a misfit in her Salem-like town, discovers that she comes from a line of superhuman witches, her mother is more than three centuries old, and her family is entangled in the history of the town and its witch-hunters. Moth’s grandmother has retreated into a timeless, otherworldly utopia for witches, while her Mom has embraced the mortal world and sworn off witchcraft. Grandmother and Mom argue over Moth’s destiny, while Moth seeks her own way. There’s an intriguing story hook in this middle-grade fantasy, which poses an ethical dilemma about retreating from, versus engaging, an imperfect world — and suggests an allegory of America, in which women of color (Moth and family) expose and challenge the culture’s white-supremacist and patriarchal origins (the witch-hunters). However, The Okay Witch seems tentative and underthought, hobbled by blunt exposition, shallow characterization, and patchy drawing. Steinkellner’s characters are designedly cute and expressive (her style reminds me of Steenz), and she seems to grow into the work as she goes, but the results are unsteady. The breakdowns and staging of action sometimes confuse, the settings lack texture and depth, image and text do not always cooperate, and distractions such as crowded lettering and jumbled perspectives dilute the impact. The novel is progressive, hopeful, and charming, much more than the pastiche of Kiki’s Delivery Service suggested by its cover, but still strikes me as a derivative, uncertain effort. Mooncakes. By Wendy Xu and Suzanne Walker. Lettered by Joamette Gil; edited by Hazel Newlevant. Roar/Lion Forge, ISBN 978-1549303043 (softcover), Oct. 2019. 256 pages, $14.99. Mooncakes is a Young Adult fantasy about witches, werewolves, and demons, set in a world where magic is — well, not commonplace, but not unheard of either. More than that, it’s a gentle romance between two sometime childhood friends, now young adults: Nova, a witch who lives and works with her grandmothers (also witches); and Tam, a genderqueer werewolf and a refugee, running from cultists who seek to exploit their power. Even more, though, Mooncakes is a paean to community: a culturally diverse, queer one that helps Nova and Tam bind demons and face down their adversaries. The complicated plot hints at a world in which the relationships between technology and magic, humans and spirits, and the living and dead could take volumes to explore. Xu’s drawing is organic and expressive, her pages lively variations on the grid, with occasional dramatic breakouts. The settings are richly textured, the colors thick, a tad cloying. The emotional dynamics are enriched with grace notes of characterization (Xu and Walker know when to take their time). That Nova is hard of hearing is a point gracefully handled, neither central nor incidental. The story is finally a bit too pat, and reworks some shopworn elements — again, there’s that whiff of Miyazaki, with animal spirits and talk of a young witch’s apprenticeship. Yet the distinct characters and budding romance make it click. The Midwinter Witch. By Molly Knox Ostertag. Color by Ostertag and Maarta Laiho; designed by Ostertag and Phil Falco. Scholastic/Graphix, ISBN 978-1338540550 (softcover), Nov. 2019. 208 pages, $12.99. The Midwinter Witch rounds out Ostertag’s middle-grade Witch Boy trilogy — though I dearly wish this wasn’t the last book, since she has created such a beguiling world and winning family of characters. The series keeps getting better, and this volume hints at conflicts and potential that could sustain even deeper explorations. Here, Aster (the gender-nonconforming “witch boy”) and Ariel (a character introduced in the second book, The Hidden Witch) and their friends attend the Midwinter Festival, a yearly reunion of Asher’s extended family. There they compete in a tournament that requires each of them to face their fears: Aster’s of defying a strictly gendered tradition, Ariel’s of not fitting in, of being the orphan and odd witch out. Acerbic and defensive, Ariel is not sure she can become part of Asher’s very welcoming family. A dark force from her past looms up, luring her to a different path and leading to a confrontation that is all too quickly resolved — I wanted to know more about Ariel’s particular darkness and its source. The payoff, though, is lovely and affirming. The Midwinter Witch is a remarkably sure-handed work of cartooning, enlivened by deft, often silent, characterization, artfully designed pages that mix the grid with bleeds and multilayered spreads, and felicitous coloring. Overall, it’s a marvel of elegant, empathetic storytelling — a new high for Ostertag. By way of conclusion, I invite KinderComics readers with insights into this genre to weigh in with comments! I'd love to hear from readers with a strong interest in this kind of story; I'm eager to gain a fuller sense of the witch's tale, where it comes from, and what it might mean for culture and for comics. I see literary, cinematic, and anime/manga influences in this genre, but still find myself wondering, why is the witch's tale flourishing now, as a comics genre? How does the treatment of the witch's tale in comics differ from its treatment in prose?

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed