|

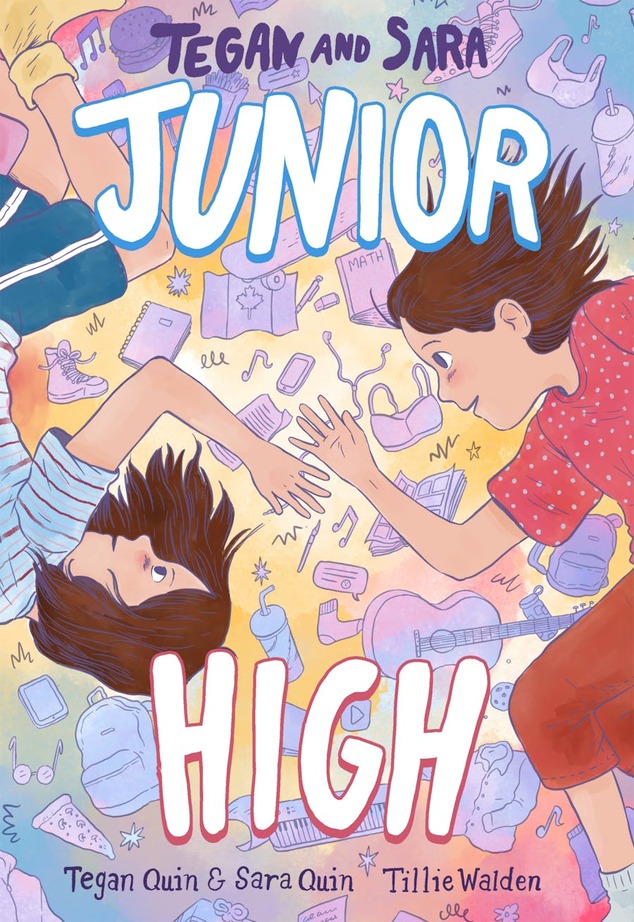

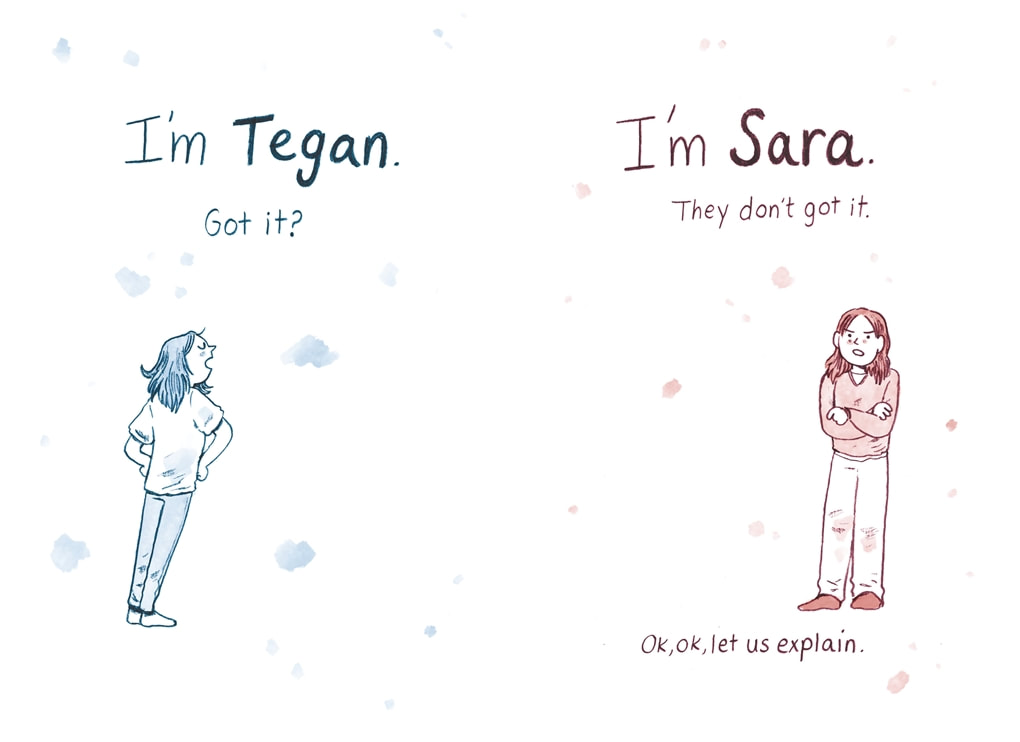

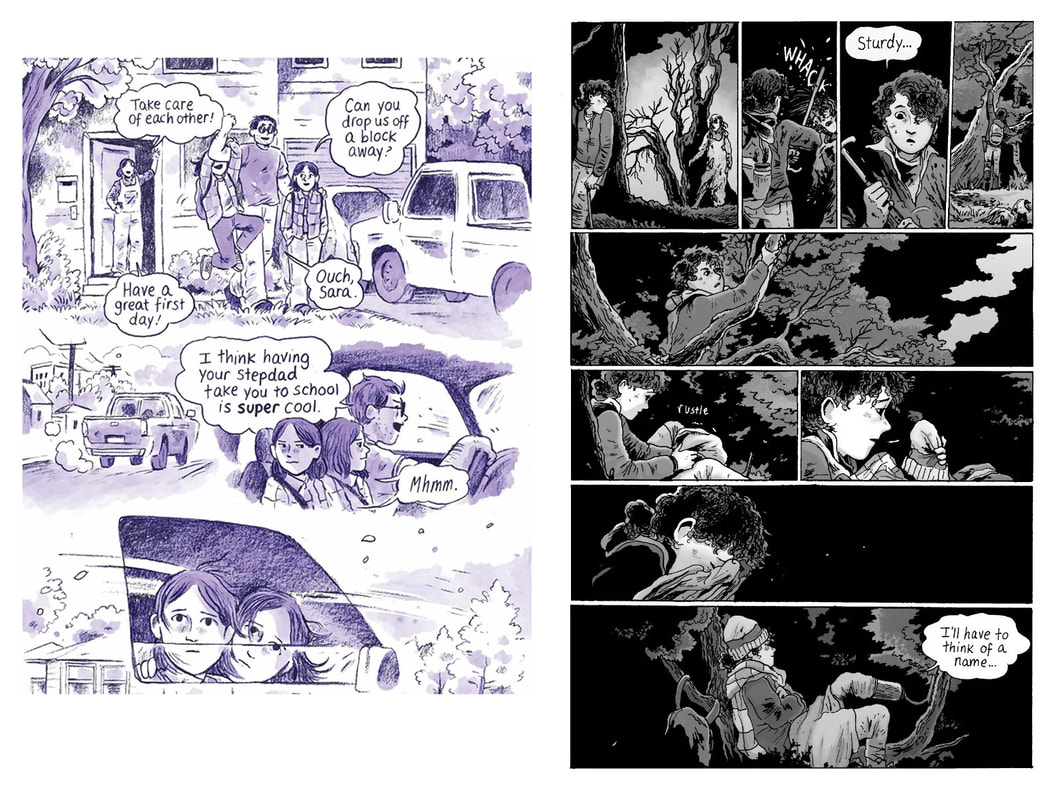

Junior High. By Tegan Quin and Sara Quin (scripting) and Tillie Walden (art). Farrar, Straus and Giroux, ISBN 978-0374313029, 2023. US$14.99. 304 pages, softcover. Tillie Walden strikes again! As ever, I'm excited to see a new book by Walden, one of America's most gifted comics artists and a particular favorite of KinderComics. I realize that this blend of fiction and autobiography (as the publisher calls it) is more likely to be billed as a true-to-life personal story by indie-pop stars and identical twins Tegan and Sara. Of course. Yet I have to admit that, for me, it began as a Tillie Walden book. It was Walden's name that got me to perk up and pay attention, and for that I'm glad. Turns out it's very well-written by Tegan and Sara, and yet another interesting departure for Walden. By now, Walden is hopefully no longer burdened with the wunderkind reputation that seemed to stick to her for her first several books. I mean, that rep was understandable — she was amazingly young for a graphic novelist, it seemed, and fearsomely prolific and good — but Walden has been productive and versatile for years, and is now a teacher at her old school, the Center for Cartoon Studies, so she's a veteran. And it does seem a bit foolish to keep marveling at how very much she has done in a short time. I'm still guilty of doing that, of course! What interests me now is the way she is departing from indy-comics expectations, branching out into different kinds of work. Since her last creator-owned graphic novel, Are You Listening? (2019), she has collected many of her early short works, co-created (with Emma Hunsinger) a collaborative picture book, undertaken a work-for-hire Walking Dead franchise series called Clementine, and now this, another collaborative work. Clementine is a trilogy in progress (the second volume is expected this fall), and Junior High promises to be the first half of a duology, so it looks as if Walden is dividing her work between different serial projects over a fairly long span. Huh. I would not have predicted these things a few years ago, but what do I know? Junior High is, we're told, a "lightly fictionalized" riff on the true story of Tegan and Sara Quin's first year in middle school, which in reality happened in 1991 but here is depicted in the present day, with all the cultural differences that that updating entails. For instance, cell phone use is near-constant here, and word balloons that represent texting are an important storytelling device. At one point (45), Taylor Swift fandom comes up in a conversation, but Swift was born when Tegan and Sara were nine! The Quins are upfront about the fact that the Tegan and Sara depicted here are "fictional" (an afterword explains some of the changes they made to their story). In essence, Junior High conveys the gist of junior-high experience circa 1991 in terms easily relatable to readers of that age in 2023. It's an interesting, if perhaps opportunistic, strategy. What matters is that the Quins write themselves and their schoolmates well, and Walden responds with graceful cartooning and beautiful pages. Briefly, the story follows the formerly inseparable twins into junior high, where their different desires and anxieties pull them apart, until their mutual discovery of music (via their stepdad's guitar, surreptitiously borrowed) brings them back together as a singing and songwriting team. Tegan and Sara are indeed hard to tell apart at a glance, and this becomes a running gag (even they sometimes confuse themselves with each other!). The two are pulled this way and that by budding social and romantic longings, with Sara crushing on one classmate, Roshini, and Tegan trying to win the approval of another, Noa, despite Noa's friendship with a bully who makes everyone feel lousy. Different forms of queer longing are gently explored, and milestones of puberty, such as the onset of periods and shopping for bras, complicate the social pressures the twins already feel. Much of the book concerns social maneuvering, the challenges of shuttling between different peer groups, the betrayal of confidences, and the awakening of desire. The writing is confident, the characterization observant and sensitive. What I love about Junior High is the delicacy that Walden brings to the story through her designs and drawing. The book is distinct from her earlier work, dispensing with framed panels and neat borders in favor of a more open, fluid aesthetic. The panels are separated by, not borderlines, but the deft use of negative space and patches of shading and color. This takes a little getting used to — the pages are still dense and busy — but only a little. Most of the story is colored only in shades of purple, recalling Walden's Spinning, but brief interludes — interchapters or pauses that punctuate the story — depict Tegan in blue and Sara in red, and drop the usual density of detail in favor of open layouts full of uncluttered white. These intervals allow the two sisters to reflect and unload in a symbolic space, underscoring their complex feelings. After Tegan and Sara discover songwriting together, Walden adds a vivid gold to the book's palette, bringing out the joys of music. I can't help but contrast Junior High with Walden's current project, Clementine, a survival horror series toned entirely in greys (by Cliff Rathburn of Walking Dead fame). The pages of Clementine, Book One, consist of tightly packed, sharply bordered panels, with layouts that grow increasingly jagged and dynamic as the story builds, leading to some manga-esque diagonals. The work is fittingly claustrophobic, combining Walden's familiar paneling with thick, atmospheric greyscales that match the story's muted horror, laconic storytelling, and emotionally stunned characters. With Junior High, Walden seems to be exercising different muscles, almost reinventing herself artistically. It's interesting to think about these two very different projects being on the boards at nearly the same time (especially coming after such disparate projects as Are You Listening? and My Parents Won't Stop Talking!, her collaboration with Hunsinger). I note that Junior High was drawn in pencil on watercolor paper, then colored digitally in Procreate, whereas Clementine was penciled in Procreate, then printed out and inked in pen on cardstock, so it appears that Walden is deliberately tacking back and forth between different methods. The penciled shading in Junior High opens up something new in Walden's art — and, as ever, I'm amazed at her hunger for growth and experimentation. In all, Junior High is a quiet joy: a smart, meticulously crafted adaptation, and another fascinating step for a wonderful cartoonist.

0 Comments

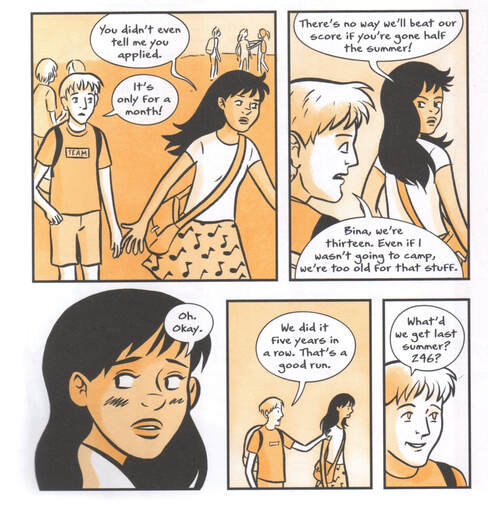

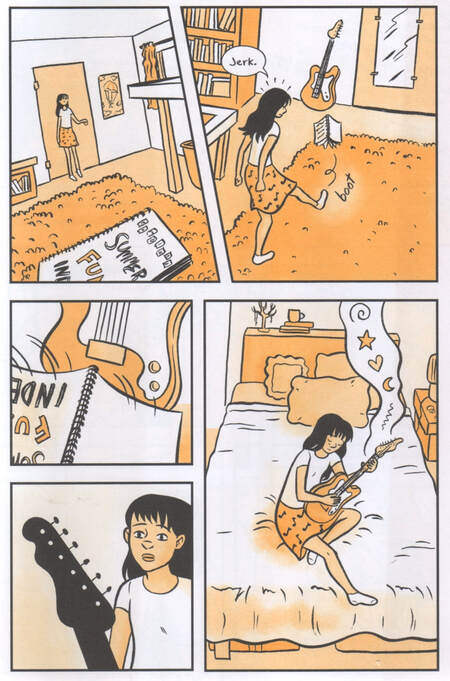

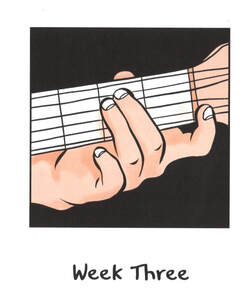

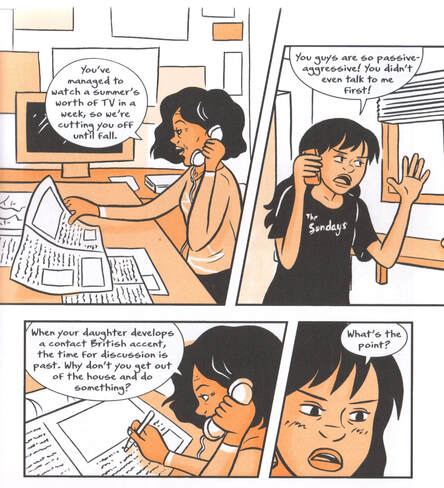

All Summer Long. By Hope Larson, colored by MJ Robinson. Farrar Straus Giroux, May 2018. Paper: ISBN 978-0374310714, $12.99. Hardcover: ISBN 978-0374304850, $21.99. 176 pages. All Summer Long is as interesting for what it doesn't do as for what it does. A teen-to-tween story of nervous friendship and awkward changes experienced over one summer, this middle-grade graphic novel hints at the familiar transition from palling around to the first tentative steps of romance—but it doesn't go there, and it's the better for it. Protagonist Bina, a thirteen-year-old girl, lives in suburban Eagle Rock, California, and has just completed seventh grade. As summer looms, she rather possessively longs for the usual months of uncomplicated fun with her best friend and neighbor Austin, but instead finds Austin changing, and her own social life unmoored. The novel recounts the ensuing summer, a bewildering stretch that, for Bina, climaxes in discoveries that kick up her musical aspirations and sense of self a notch. Romance plays a part in all this, but it's not the romance of Bina and Austin, nor indeed any kind of courtship story for Bina; instead it's about growing up a few small steps. Bina's story is not starkly gendered, nor does it follow a heteronormative romance plot. Rather, it's about one particular girl with a passion for music, anxious not to be left behind by her best friend but also learning that the two of them can be separate, different people. Modest in scope—the book spans just ten weeks or so—All Summer Long does not boast a complex, nail-bitingly suspenseful plot or pose terrible moral dilemmas. It's all about characterization and observation, in one short, focused, tightly-written arc. As such, it plays to author Hope Larson's strengths. The plot setup is simple. Austin's month-long sojourn at soccer camp upends his and Bina's fond summertime tradition of keeping a "combined summer fun index" (a playful numeric scoring system): Bina, feeling adrift, gets mad, sad, bored, and, finally, musical, playing her guitar and getting into a favorite new band: Bina tries to keep up contact with Austin via texting, but long silences from him, and then telltale signs of separateness or withdrawal, leave her feeling lost. She strikes up an odd friendship with Austin's much older sister, Charlie, but there the age differences prove too great for anything like an equal friendship. Austin returns from camp different than when he left, and needs space; Bina feels rejected. Even the shared experience of a gig by Bina's favorite new band doesn't help. The two friends fall out—but then Bina learns what's really been going on with Austin, a discovery that brings reconciliation while also definitely canceling any possibility that the two will pair up romantically as per the stereotypical adolescent courtship plot. The book ends by affirming Bina's budding sense of identity as a musician (an emphasis hinted at by the cover and the chapter breaks, which suggest her dedication to guitar practice). Mild spoiler: her friendship with Austin, though now less exclusive, endures. The events of the summer look different in the rear view mirror, so to speak, and Bina enters eighth grade with a newfound sense of who she is and what she wants. The denouement is both definite yet open-ended enough to invite the reader to think about what's coming next (online info suggests that All Summer Long is part of an "Eagle Rock Trilogy," though I saw no signs of this on the book itself). All Summer Long recalls Larson's early graphic novel about summer camp, friendship, and coming of age, Chiggers (2008). Aesthetically, its tangerine-soaked two-color scheme (courtesy of colorist MJ Robinson) gets closer to her adaptation of A Wrinkle in Time (2012), in which a light blue served as the second color. Larson has become increasingly fluent and emotionally nuanced as a cartoonist (Wrinkle, a demanding project, seems to have tested and extended her skills). All Summer Long is not a subtle or elusive text; the important thing is that the art communicates, words and pictures working in tandem, keyed to physical action but especially to the rhythms of dialogue. In fact, dialogue is one of Larson's not-so-secret weapons. Her characters have a sense of humor, and know how to spar verbally. Dialogue exchanges are brisk, and Larson has a playful way with language:  I confess, though, that I don't find Larson's drawings very transporting. They are good at conveying the in and out of relationships and the lived-in business of feeling and negotiating. They're likewise good at putting characters in spare but habitable spaces, and working out their interaction visually and physically. Only occasionally do they give off any mystery or magic. This was a problem for some of my students, and for me, when I recently taught Larson's Wrinkle alongside Madeline L'Engle's original novel. Larson's adaptation does many things well: it is patient, thorough, as close to the details of L'Engle's text as it can get, and yet eminently readable. Larson (and her publisher) made a good decision in letting the story breathe and expand (up to near 400 pages), a call that too few makers of comics adaptations of literature are willing to make. Larson's Wrinkle cleaves to L'Engle, parses out the action carefully, and seeks to uphold the original's weirdness (despite Larson's confessed aversion to L'Engle's religious themes). She does all she can to give the novel a measured, thorough, and deep treatment. But when it comes to depicting the spiritual, the metaphysical and cosmic, the book falls oddly flat, with prosaic images that, perhaps inevitably, cannot capture L'Engle's use of paradox and self-cancelling figures of speech. My students were quick to pick up on L'Engle's impossible descriptions, which at once invite but frustrate any literal visual depiction. They were also quick to criticize Larson's pages for not living up to those mystical, or I might even say theological, moments. Those passages appear to call for an escape from the grid, from careful, measured steps, and a plunge into the odd and disorienting. Larson doesn't really deliver that, though. She does use layout ingeniously to convey the impossible experience of tessering (transporting), but her alien vistas and creatures tend to be rather ordinary. It's clear from Larson's work as a comics writer (for example, the seafaring adventure of Four Points, with artist Rebecca Mock), or indeed from the magical elements of her early graphic novels (e.g., Gray Horses; Mercury), that she has a yen for the fantastical, but her own drawing seems more methodical than dazzling. All Summer Long, again, plays to her strengths. Larson has been a prolific creator, from her early burst of original graphic novels (2005-2010), through the long haul of Wrinkle, to a lot of subsequent work writing for other artists: again, Four Points, but also Who is AC?, Goldie Vance, and Batgirl. (She has also written and directed a short film.) All Summer Long is her first solo, self-drawn book since Wrinkle, and comes after a brief period during which, it appears, she struggled to sell a new graphic novel, but then moved into a long spell of collaborative work, much of it in periodical form. After all that, All Summer Long seems to tack in the direction of current tastes; it's the kind of book that is all the rage in graphic novels today: namely, a middle-grade coming-of-age story about and for girls. This is not startlingly new territory. But Larson is good, very good, and if All Summer Long leads to a series of books in a similar vein, they will be worth the reading.

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed