|

Wildful. By Kengo Kurimoto. Groundwood Books / House of Anansi Press, ISBN 978-1773068626, February 2024. $US22.99. 216 pages, hardcover, 9.625 in x 6.75 in (landscape format). Wildful is a beautiful graphic novel about getting yourself lost in the woods. Or, I'd say, about deep ecology, immersion in the environment, and biophily. It at once takes a posthumanist view (avoiding anthropocentrism and decentering human ego) and yet argues a deeply humanist viewpoint, that losing ourselves in the Wild is a way of recovering our best selves. Specifically, it's a book about biophilia as a salve for grief. It is a sparsely dialogued, in fact mostly wordless book in landscape format (for wide vistas), toned in warm sepia, and drawn naturalistically rather than cartoonishly. I hadn't known about the author, Kengo Kurimoto, til I picked up this book on a whim at my local library. Kurimoto is a game designer (LittleBigPlanet; Dreams) and animator, and Wildful is his first graphic novel. Its organic look differs from the obviously digital artwork that tends to dominate his website (though if you dig deeply enough, you'll find analog as well as digital treasures there, in plenty). Kurimoto highly values unmediated sensorial experience and close, patient observation, and he prioritizes drawing from life rather than using cartoon schemata. In Wildful, the results are rather stunning. This is a book about patiently, patiently, observing the natural world and finding yourself changed in the process. The plot, in outline, is simplicity itself: A young girl named Poppy and her dog Pepper accidentally discover the wild woods behind their house, where they meet a new friend, Rob, whose loving, unhurried appreciation of the environment rubs off on them. Over the course of several days hanging out with Rob, Poppy begins to notice and question more, and to luxuriate in her surroundings. She comes to experience the natural world more deeply. Poppy longs to bring her Mum out to the woods with her, but Mum, who is still grieving the loss of her own mother, is depressed, withdrawn, and housebound. The book's resolution brings Mum out of the house and involves an overnight kip in the woods. The story is that basic. There are four characters: three humans, one dog. We don't learn much about the circumstantial details of their lives. We come to know very little of Poppy's family or backstory, and next to nothing about Rob's other than the fact that he finds solace in the woods. What matters is the process of their shared discoveries and the adventure in perception and empathy that they undergo. On the level of paraphrasable content, or abstracted themes, Wildful is, again, simple, or it's the kind of thing we are tempted to call simple — but as an experience, it's stunning. The storytelling is mostly mute and relies greatly on Kurimoto's minutely observed, naturalistic drawing, warm shading, and unhurried pace. Most pages are multipanel sequences, but some are single panoramic drawings (see this great page about his process). The book can be read in a few minutes, or, better, reread slowly and luxuriated in. You owe it to yourself to experience this.

0 Comments

Plain Jane and the Mermaid. By Vera Brosgol. Color by Alec Longstreth. First Second, ISBN 978-1250314857, May 2024. $US14.99. 368 pages, softcover. Vera Brosgol is one of my favorite artist-authors in the children's graphic novel field. She's back with a new book, her first graphic novel since 2018, and it's a doozy. Mind you, Brosgol has not been idle. These past six years, she has, by my count, written and illustrated two picture books, illustrated two more, and worked as head of story on the film Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio. Whew! I'm glad to have a new graphic novel by her. Plain Jane and the Mermaid is a feminist fairy tale about outward appearances versus inward self-worth. It's also an inventive, and occasionally spooky, phantasmagoria that takes place almost entirely underwater. Jane, a "plain" young woman of apparently few prospects, dives into the deepwater world of selkies, sea monsters, and mermaids in order to rescue (?) Peter, a mermaid-stolen man with whom she thinks she has fallen in love. She hardly knows the guy, but he is beautiful, and she has asked him to marry her. Marriage is Jane's one hope, because, as the last survivor of a household without a male heir, she is about to be turned out of her home by a distant and uncaring cousin: A mysterious crone magically grants Jane the ability to survive underwater, and so Jane takes off in pursuit of her hoped-for husband. In the meantime, Peter is wooed and pampered by a trio of mermaids, little suspecting what they may have in store for him. Things turn dark(er) when Peter learns what it is that mermaids actually do with humans, but meanwhile Jane develops a comical yet genuine friendship with a seal who turns out to be a selkie, and her plainness (if that's what it is) no longer matters. There are twists and surprises en route, and the story ends delightfully, with a sense that various dangling loose ends have been tied up, or tied together, in unexpected but apt ways. It's the kind of well-engineered book where nothing goes to waste, and small details glimpsed along the way turn out to be openings (or deepenings). Brosgol's story-world is cruel. Parents and peers judge and shame; rivals tease and bully. Plainness of face and stoutness of body are condemned. Appearances count, and mirrors are threats. Beautiful people get unearned perks and learn to rely on them, while ordinary, unlovely people are expected to scrape and crawl. Social outliers are sacrificed for the comfort of the socially advantaged. Women get the short end of most everything, and predation and hunger rule. Some readers may be taken aback by the harshness of this world, but to me it seems honest enough. Some may be alarmed by certain terrible comeuppances that are meted out. The story is tough. Moreover, some undersea scenes are scary, as when, on a sunken ship, corpses come groaning to life and close in on Jane, or when a giant anglerfish almost snaps her up in its jaws, or when a mermaid bares her teeth. Brosgol isn't scary in quite the same way as, say, Emily Carroll (whose take on mermaids is positively terrifying); she pushes only a little at what middle-grade books usually allow. But she does push. Me, I love these moments of risk-taking. Her graphic novels always play for keeps, and that wins me over. So, Plain Jane is a recognizable Vera Brosgol book. Yet Brosgol deserves credit for making each book look and feel a little different. Plain Jane doesn't look that much like Anya's Ghost or Be Prepared (they don't look that much like each other, either). This one feels a bit rawer in the rendering, I'm guessing deliberately, but at the same time uses a full color palette, courtesy of color artist Alec Longstreth — a great cartoonist in his own right, and a great graphic novel colorist. He does a lot of heavy lifting here. (It's a shame Longstreth's name isn't on the title page where it should be. Though the back matter reveals some of the coloring process, and Brosgol praises "Alec" effusively, you have to read the fine print to find his full name.) Despite surface changes in style, Plain Jane boasts Brosgol's usual distinctive character designs, expert timing, and gift for small shocks. This is clear, classic cartooning. The book is not the revelation that Anya's Ghost was, but it's thrilling. Its roughly 350 pages pass too quickly, a fierce, lovely dream. The final affirmation of Jane's self-worth is not surprising — in that sense, the book ends where most of us would want it to end — but the trip is full of little gemlike touches. Vera Brosgol really is a gift, you know?

Paul Bunyan: The Invention of an American Legend. Comic by Noah Van Sciver, plus essays and art by Marlena Myles, introduction by Lee Francis IV, and postscript by Deondre Smiles. TOON Books, ISBN 978-1662665226, 2023. $US17.99. 52 pages, hardcover. Paul Bunyan: The Invention of an American Legend is another TOON Graphic that juxtaposes a compelling comic with carefully curated (front and back) editorial matter. In this case, the introduction and back matter are not just instructive supplements but pointed rejoinders to the comic, and essential to the book's overall effect. Noah Van Sciver's comic takes up 36 of the book's 52 pages, but the remaining pages are emphatically not filler. What we have here is a package that both burnishes and yet undermines the "legend" of the faux-folkloric lumberjack, Paul Bunyan, with Van Sciver casting a skeptical eye on how the legend was promulgated while the other features remind us of what the legend hides. It's a great and startling project. I wish it had been among the Kids nominees for this year's Eisners, and was glad to see it among the finalists for this year's Excellence in Graphic Literature Awards (which is what reminded me to write about it here). Noah Van Sciver has become one of my favorite cartoonists. He is a terrific humorist and memoirist (his hilarious autobio comic, Maple Terrace, was one of my favorites from last year). What's more, he is one of the US's best and most prolific creators of historical and biographical comics (his brave book Joseph Smith and the Mormons is just the iceberg's tip). Paul Bunyan feels like it's right in his wheelhouse. The story, a fiction inspired by fact, takes place in Minnesota in 1914 on a westbound train, as lumber industry ad man William Laughead regales his fellow passengers with yarns about Paul Bunyan, "the best jack there ever was" and the epitome of the industry's clear-cutting zeal. Laughead's crazy, mythmaking anecdotes have the zestful absurdity of tall tales, and Van Sciver knows how appealing such tales can be. A shameless fabulist, Laughead imagines Bunyan as an unstoppable giant-sized version of himself. He meets challenges posed by skeptical listeners with a game face and ever-escalating bunkum. Van Sciver portrays him as folksy, funny, a bit desperate, and basically a shill. More critical perspectives are provided by other characters, especially a disillusioned lumber industry vet. The art is lively and joyous, but also insinuating, and the textures (drawn in ink but then colored digitally) are trademark Van Sciver. This is beautifully organic and readable cartooning. You could say that this is Van Sciver's project (the indicia assigns the copyright to him and TOON), but the elements provided by other creators are vital. Those elements, from Native writers and artists, decry the "seizure of homeland" and environmental devastation spurred by America's rapacious lumber industry, and champion forms of history and knowledge obscured by the aggressive expansionism of the Bunyan myth. Lee Francis IV (Pueblo of Laguna), well-known as an advocate for Native comics, provides a wisely ambivalent introduction. Deondre Smiles (Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe), critical geographer and academic, supplies an informative and well-illustrated essayistic postscript about the links among colonization, land theft, and deforestation. Marlena Myles (Spirit Lake Dakota), a multidisciplinary artist, provides essays, a bilingual, Dakota and English map, and strikingly stylized illustrations and endpapers. There is a meeting of talents and perspectives here that suggests careful project management (by editor Tucker Stone and editorial director and book designer Françoise Mouly). The whole definitely exceeds the sum of its parts. Paul Bunyan is the kind of project I've come to expect from TOON: distinctly individual, yet collaborative; personal, yet proactively curated by an expert editorial team. More than further proof of Van Sciver's historical imagination and cartooning chops, it's a multifaceted group effort, the kind that is needed when you're demythologizing and debunking an entrenched bit of Americana. It's a short read, but excellent, and I find myself paging through again and again with admiration.

This post is the second in a series of three. Yesterday I reviewed this year’s Eisner Award nominees for Early Readers. Today I turn to the nominees for Kids, which I assume means roughly middle-grade readers, around 8 to 12 years old (see my post of May 17 for an overview of all young readers’ categories). Once again, I’ve tried to describe every book fairly, while acknowledging my favorites. I’ll be back soon with a third and final post about the nominees for Teens. This is all about getting ready to cast my votes before the June 6 deadline! (For information about voting, see here). Buzzing, by Samuel Sattin and Rye Hickman (Little, Brown Ink) A book for our time: a neurodivergent Bildungsroman, plus a paean to creative and queer community, in the form of a Dungeons & Dragons-like RPG that gives the protagonist, a young man with OCD, a group of nonjudgmental friends with whom he can be free. He just has to persuade his anxious mother that playing the RPG will be good, not bad, for him. OCD is a familiar topic in disability-themed comics, but Buzzing does something new. Intrusive thoughts are cleverly represented through visual metaphor (a swarm of bees, buzzing), while the cartooning is lively and the cast delightful. Vivid! Mabuhay! by Zachary Sterling (Scholastic Graphix) A Filipino American brother and sister struggle to balance assimilation pressures at school with filial obligations at home. Forced to work on their family’s food truck, they are alienated and resentful – until their family must unite to, I guess, save the world? This acculturation fantasy starts with everyday complaints and embarrassments, then lurches into magic and monsters inspired by Filipino folklore. Sterling’s elastic, manga-flavored cartooning shows his expertise in animation design: characters are distinct, and emote hugely, with broad expressions. The action is frenetic; the plot feels juryrigged. The lessons in filial piety are rather on the nose, I think. Mexikid: A Graphic Memoir, by Pedro Martín (Dial Books for Young Readers). This memoir made my Best-of-2023 list for The Comics Journal. Young Pedro, his many siblings, and mom and dad make an epic road trip to the family’s ancestral hometown in Mexico, there to reunite with his grandfather. Americanized Pedro is often startled by what he learns on the way. Exuberant and graphically tricky, with many inventive, diagram-like pages, Mexikid is a loving tribute to family in all its quirkiness and complexity. In the home stretch, Martín shifts, convincingly, from hilarity to grief, tenderness, and new depths. I’m teaching this in the fall, and it’s my strong favorite in this category. Missing You, by Phellip Willian and Melissa Garabeli. translation by Fabio Ramos (Oni Press) Neotenic cuteness (think Bambi) vies with hard-won lessons about grief and letting go in this gorgeous, disquieting book. A family nurses a wounded fawn back to health, even as they cope with the loss of one of their own. Caring for the deer seems to heal their own hurts, yet they know the deer must someday go back to the woods. Prepare yourself for the inevitable parting (and note, along the way, the deer’s own sad backstory, its own remembered parting). Garabeli’s sumptuous watercolors and elegant pages boost the already considerable power of this of course manipulative, yet beguiling, heartwringer. Saving Sunshine, by Saadia Faruqi and Shazleen Khan (First Second) Feuding twins, sister and brother, make peace during a family trip to Key West. There they learn to care for each other, even as they nurse an enormous loggerhead turtle that lies ailing on the beach. As Muslims from a Pakistani American family, they share a history of struggling against racism and Islamophobia, which informs both their quarreling and their reconciliation. Rendered in digital watercolor, with some lovely, open pages, this book at first leans into adult-centered didacticism (these kids need to learn a lesson), but happily brings nuance and sympathy as it goes. So: predictable arc, but surprising details. Some final thoughts: I'm surprised that Dan Santat's A First Time for Everything was not nominated in this category. It is contending in the category of Best Graphic Memoir, though. (Interestingly, most of the nominated memoirs this year could be considered either middle-grade or YA books.) I obtained all of the above books from the Los Angeles Public Library, save one, Missing You. My sense is that graphic novels published by the children's imprints of the "Big 5 (Hachette, HarperCollins, Macmillan, Penguin Random House, Simon & Schuster) are easy to find in LAPL. Unsurprisingly, so are books from Scholastic, the market leader in children's GN publishing. With other presses, or children's imprints that are not so well known, I had trouble; for example, I could not find a couple of nominated books from Oni Press. We know that the middle-grade graphic novel is (besides manga) the busiest and most profitable sector in US comics publishing. It is also a sector that produces a lot of formulaic work. Reigning themes in middle-grade comics perhaps reflect reigning themes in children's book publishing, period: social negotiation among friends, acculturation, loyalty to family and culture, displacement, loss. Often an adult-centered didacticism clings to books with these themes: I note that the young protagonists of Mabuhay! and Saving Sunshine complain about their parents' decisions, but there is never any suggestion that the parents might need to question their choices (what parents do is not up for debate). When reading middle-grade comics, I often have a feeling that I know just what is happening, and what prosocial messages are meant to be reinforced. I get impatient with that feeling. That said, I've enjoyed reading almost all of this year's middle-grade nominees. To me, the most interesting ones by far are Buzzing and Mexikid, as they are the most formally inventive. It happens that they are also the ones that most clearly resist the thumping didacticism I'm complaining about. Not coincidentally, they have the most complex adult characters as well (though props to Missing You for showing adults and children grieving together). Still to come: this year's Teen nominees!

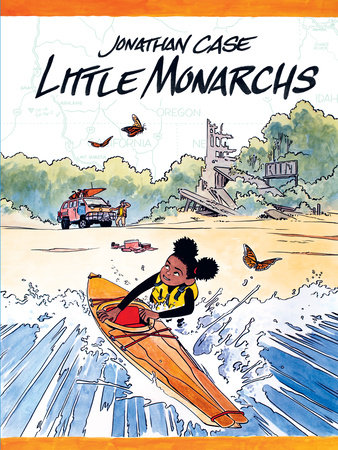

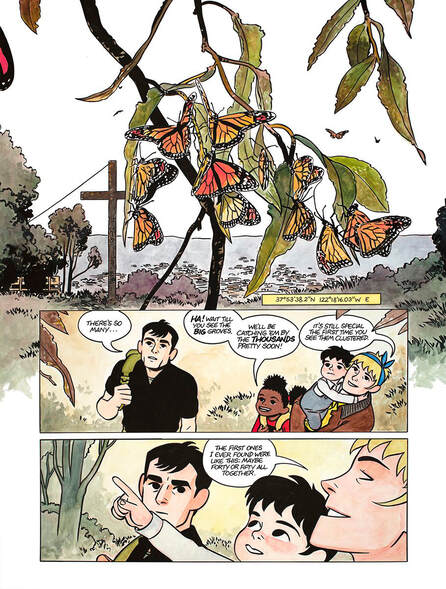

Little Monarchs. By Jonathan Case. Holiday House/Margaret Ferguson Books , ISBN 9780823442607 , 2022. US$22.99. 256 pages. A Junior Library Guild Gold Standard Selection. This post comes belatedly and is not much more than a mash note. A few days ago, I called the Eisner Award-nominated Little Monarchs, by Jonathan Case, "an extraordinary piece of worldmaking, ... dense, involving, subtle, and beautiful." I stand by that. It is one of the best graphic books for readers of any age I've read in a while (and I've been reading a lot of good ones lately, now that school is out). I dove into Little Monarchs hurriedly, without doing my usual obsessive reading of paratexts, indicia, and so on (I'm usually a bit compulsive about how I crack open books that are new to me). I had the book out from my local branch of LAPL and was bingeing before casting my annual Eisner votes, so I was rushing. I hadn't even read the jacket copy. So, it wasn't until I finished the first of the book's dozen chapters that I began to realize that the story was set in a world I did not quite recognize, or a changed version of our world where something had gone wrong (I overlooked a detail given on the first page: that the date is 2101). In fact, Little Monarchs is a post-apocalyptic survival story, though officially a middle-grade (ages 8-12) sort of book. In it, a ten-year-old girl, Elvie, and her guardian, a forty-something biologist named Flora, drive through a drastically depopulated North America in which most people dwell underground, unable to travel safely in sunlight. Elvie and Flora mostly avoid encounters with these "deepers," preferring to go it alone. They dread attacks by "marauders," that is, scavengers who would pirate their stuff.  So, the world of Little Monarchs is different. In it, about fifty years have passed since a "sun shift" has killed off most mammal life. Prolonged exposure to direct sunlight (more than a few minutes) can be fatal. Most human survivors are socked away in underground bunkers, and only a few crepuscular or nocturnal mammals, such as bats, can hope to survive. Flora and Elvie are able to live topside because Flora has developed a medicine that keeps them safe from "sun sickness" for up to about a day and a half at a time. The medicine derives from the milkweed within monarch butterflies, so Flora and Elvie follow the yearly path of the monarchs' migration, catching butterflies, harvesting scales from their wings, releasing them, and creating ever more batches of meds. At the same time, Flora seeks a more permanent solution in the form of a heritable vaccine. Little Monarchs, then, is the story of an never-ending road trip and a scientific quest. Remarkably, this survival story reads less like horror and more like an adventure. That has everything to do with the character of Elvie, a Black girl who is resourceful, eagle-eyed, courageous, decent, and funny. Elvie explores and improvises and above all uses her head. She can face down her fears and make do when disaster strikes. The heart of Little Monsters is the bond between Elvie and Flora, her White caregiver, who is something like a mom, big sister, tutor, and friend all at once, and whose quirks Elvie knows and forgives. You can believe that these two understand and love each other. The book gains heft from Elvie's journal entries: expository interludes that serve to orient the reader while showing off her smarts. These entries combine Elvie's home-school assignments (given by Flora), drawings, reflections, and tips. Elvie knows how to live in the wild world Jonathan Case has imagined, and her entries impart a great deal of knowledge. Case has mapped her story onto real locations, using real geographic coordinates, and included a wealth of fascinating detail about everything from knot tying to the monarchs' life cycle. The story-world fits this girl to a tee, and vice versa. Little Monarchs takes interesting risks. As a survivalist story in a broken world, it delves into the hard ethical questions that such scenarios tend to pose: What are you willing to do to survive? Do the ethical constraints of civil society apply when the world has been upended? Must you be willing to hurt others to protect yourself? The story kicks into gear when Elvie finds another, much younger child wandering in the sunlight and has to take him in, which leads to Elvie and Flora nervously weighing the risks of involvement with other people. At first, Flora seems somewhat mistrustful, even phobic, about taking that risk, but, as things turn out, she has good reason to be. There are reversals, betrayals, and shocks in the story. The last act depicts hard things — and Elvie has to do some hard things, too. Little Monarchs isn't The Road, of course (RIP to the brilliant Cormac McCarthy), but does ask its readers to weigh questions of ethics and risk in the face of grave danger. Somehow it does this and remains a thrilling adventure and credible middle-grade story about a plucky ten-year-old kid. And the visual artistry of it! Little Monarchs is a feast of lovely images made by hand, from the lettering to the gorgeous watercolors. Reading it against a backdrop of other recent graphic novels for young readers, even good ones, I was reminded of how seldom I get to see work at this scale that is handcrafted even down to its finest details. Case is a terrific comics artist, designing dynamic pages, drawing believable characters and environments, pacing and punctuating riveting sequences of high-stakes action as well as quiet scenes of discovery, and making every detail count. As I said a few days ago, he cartoons with an economy and grace that recall Alex Toth as well as latter-day classicists who have drunk from the same well: Jaime Hernandez, R. Kikuo Johnson, and Chris Samnee. His character designs, breakdowns, staging, and layouts are equal to his terrific writing. Little Monarchs urges engagement with the natural world and offers readers all sorts of potential adventures off the page as well as on. You could take this book on the road with you and learn a lot. More than anything, it is a classic quest story, pulled off with warmth, wit, and bravery, surprising and gutsy right up to its very last page. After reading so many well-intended moral and political fables for children in which messages are reliably delivered and conclusions are just what one would expect, I took delight in its splendid eccentricity. Highest recommendation!

I like to keep up with the Eisner Awards. I'm a former judge, I value recognitions of excellence in the comics world (even when they're contentious), and I like staying in touch with the process. Honestly, it can be hard to find and read every single nominee, but each year I pay particular attention to, and try to spend time with, all the nominees in the young readers' categories. Currently, that means three categories: Early Readers, Kids (ages 9-12), and Teens. Over the past week, I've read about ten books to get up to speed! I'm told that today, June 9, is the last day to cast votes (officially, the vote is "open until June 10, 2023 12:01 AM (GMT-05:00) Eastern Time"). So, this evening I'm going to vote in as many categories as I feel qualified to vote in! This year's Eisner process has been especially vexed and controversial (leading to a retroactive withdrawal from the ballot). The ballot has been a bit mystifying to me, with some, IMO, startling omissions and puzzling categorizations. But controversy is in the nature of the awards, and I still appreciate the heuristic value of this, let's say, yearly exercise. Here are my thoughts on the Early Reader, Kids, and Teens categories:  Early Readers: I admit, this is not a category that interests me much this year. There are some lovely images here (for sheer sumptuousness, Dav's Disneyesque watercolors are hard to beat), and some nice comic bits (the page-turns of Higgins, the pacing of Willems), but for the most part these books strike me as pat and aesthetically undaring. There's a lot of shtick here, which tires me out. I miss seeing some good TOON Books in this category; 2022 seems to have been fallow for them. That said, my choice here is this charming, quietly ironic, aesthetically delicate take on friendship and learning:  Kids (9-12): This is a more interesting category by far, in fact one of the deepest in this year's ballot. The craft on display is impressive (dig the cartooning in Frizzy and Swim Team), and the ambition (dig the near-wordless storytelling of Isla to Island, a complex tale of immigration, loss, and discovery; or the interactive, formally ingenious Adventuregame). But my hands-down choice is Little Monarchs, an extraordinary piece of worldmaking, which is cartooned with an Alex Toth-like economy that reminds me of elegant classicists like Jaime Hernandez, R. Kikuo Johnson, and Chris Samnee. An amazing book, so dense, involving, subtle, and beautiful: Teens: It's nice to see Tillie Walden in this category, for a book that is a change of pace for her. But I think the outstanding title here is the already much-talked about, groundbreaking Wash Day Diaries, a suite of stories about four Black women and the strength of their friendship and interconnection. Every character in this book has a backstory, but Rowser and Smith smartly leave us guessing, focusing on the energy, grace, and good humor of the four. Darkness marks the edges of the story, but joy wins out. The book seems casual, the way eavesdropping on good friends can, but that's deceptive; there's a lot going on. The chapter devoted to their "group chat" is a wonder of form as well as characterization. I admit that I didn't see this as a YA book at first, but then, I usually have that reaction to books that turn out to be very good YA books! A few observations:

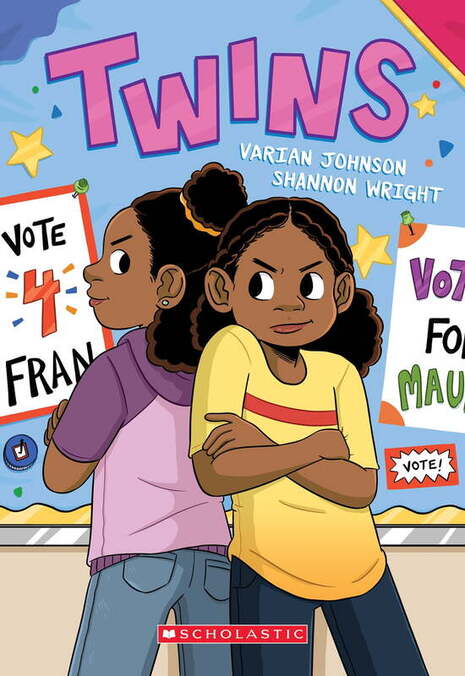

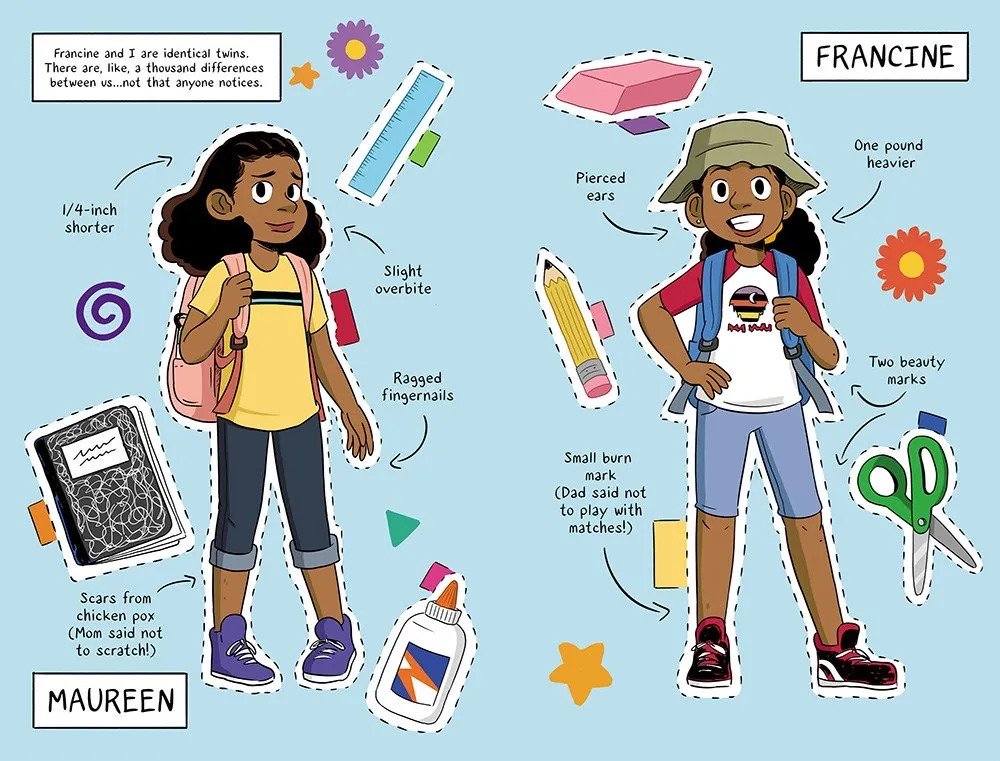

Twins. By Varian Johnson and Shannon Wright. Scholastic/Graphix, ISBN 978-1338236132 (softcover), 2020. US$12.99. 256 pages. Last week I belatedly read Twins, a much-praised middle-grade graphic novel published by Scholastic in 2020 — a first graphic novel for both writer Varian Johnson, who is a prolific novelist, and artist Shannon Wright, who has illustrated a number of picture books (most recently, Holding Her Own: The Exceptional Life of Jackie Ormes). Twins is good, but left me wanting more. The plot concerns identical twin sisters, Maureen and Francine, who have always been close but begin to pull apart as they enter sixth grade. They end up running against each other in a student body election, a rivalry driven by mixed or confused motives that hurts their relationships with friends and family. The book boasts many nicely observed, sometimes poignant, details: novelistic good stuff. The plotting balances the twins' need for individuation against their strong bond, with a sense of earned insight for both sisters. There are astute cartooning choices along the way, including full-bleed splash pages that capture moments of struggle, hurt, and growing realization. Compositionally, Wright delivers, with emotive characters, startling page-turns, and a confident grasp of what's at stake dramatically. Twins, I admit, strikes me as more reassuring than challenging. It's on familiar middle-grade turf, with a story of girls becoming tweens and growing more sensitized to social nuances and strained friendships. There are soooo many graphic novels currently working this turf. The setting is anodyne: a comfortably middle-class suburbia with dedicated students, supportive teachers and families, wise parents, and lessons on offer about self-discipline, self-confidence, and leadership. Loose ends are tied and every arc resolved, or at least reassuringly advanced, by book's end, with no one coming off the worse. Some elements, however, seem under-thought or cliched — for instance an ROTC-like "Cadet Corps" at the school, a plot device that allows for a fierce, drill sergeant-like teacher and moments of tough discipline for the more timid of the two sisters, who of course comes out the stronger (but oh the unexamined militaristic overtones). The book is inclusive and aims to be progressive, focusing on protagonists of color (Maureen, Francine, and their family are Black) while downplaying the usual generic thematizing of racism and classism as "problems" to be suffered through (a tendency expertly spoofed by Jerry Kraft in New Kid). One scene deals with shopping while Black and implies a critique of unspoken racism, but that thread isn't woven through the whole book. That in itself might be refreshing; the book thankfully avoids potted depictions of racialized suffering and trauma. Yet for me there is too little sense of social or institutional critique; the twins' relationship and personal growth are the main things, to the point of presenting adult choices uncritically and tying up the story without any lingering sense of mystery or depths remaining to be plumbed. In a word, it's pat. Perhaps I'm guilty of wanting this middle-grade book to be more YA? That wouldn't be fair, of course. But Twins is one of so many recent graphic novels that, from my POV, appear boxed in by children's book conventions, more specifically by the rush to affirm and reassure. The contours of this kind of book are starting to seem not just clear, but rigid. Young Adult books too have their conventions, one being skepticism of adult choices and institutions, and I don't know if I'm asking for that. Perhaps what I'm wishing for is something else: a touch of mystery, maybe, or a respect for the unfinished business of living. Twins is a traditional tale well told, with all its arcs well finished and its major characters affirmed and advanced. I just can't imagine re-reading it for pleasure. Some readers will stick to the book like glue, I expect. The characterization of the twins is complex, and Maureen, who is the book's focal character and real protagonist, is especially well realized: a socially anxious nerd and academic overachiever but not a shrinking violet, not a cliché. Johnson and Wright know these characters and treat them kindly; their dialogue clicks. Plus, the art is full of smart touches, and Wright offers clear, crisp cartooning and dynamic layouts throughout. Some moments registered very strongly with me: for example, the scene early in the book where Maureen and Francine get separated at school and a page-turn finds Maureen stranded in a teeming crowd of other kids, lost. Yet the book's brightness and formulaic coloring, which favors open space, solid color fields, abstract diagonals, and color spotlights, strike me as simply functional, and in the end more busy than harmonious. While Wright excels at characters, the settings appear textureless and a bit bland. Her page designs are restless, inventive, and clever, the storytelling clear, yet the governing sensibility seems, again, generic to my eyes. It's right in the pocket for post-Raina middle-grade graphic novels, but doesn't grip me. The middle-grade graphic novel is one of the most robust areas in US publishing, and the novel of school, friendship, and social navigation is its nerve center. Twins is a fine example of that. I think I'm becoming more and more jaundiced about that kind of book, though. I can now see the outlines of a formula, and I'm getting jaded. I admit, this realization has me rethinking the bright burst of enthusiasm with which I began Kindercomics five years ago.

I'm honored and delighted to be giving a talk as part of the Los Angeles Public Library's West Valley Big Read focusing on Jen Wang's graphic novel, The Prince and the Dressmaker (the first book I ever reviewed here on KinderComics). Jen Wang is one of my favorite cartoonists, and The Prince and the Dressmaker one of my favorite books of the 2010s. In fact, I'd say it's one of my top ten graphic novels of the past half-decade. So doing this talk is a real treat! As the above flyer says, the talk is happening at the West Valley Regional Branch Library on Saturday, July 23, at 11:00 a.m. LAPL has more information about the talk here: https://www.lapl.org/whats-on/events/lets-talk-graphic-novels. Readers, I hope some of you will be able to make it — and please help spread the word!

Shirley & Jamila’s Big Fall. By Gillian Goerz. Color flatting by Mary Verhoeven. Dial Books, 2021. ISBN 978-0525552895, US$12.99. 240 pages. The first comic I read in 2022! I read it on January 1. I thought I'd break out of my self-imposed hiatus to write this quick review: More complicated and less charming than the first Shirley and Jamila book (which I reviewed almost exactly a year ago), this one adapts a Sherlock Holmes tale by Conan Doyle into a somewhat incredible middle-grade story of bullying and comeuppance, one in which Shirley and Jamila commit burglary and break a lot of rules in order to solve a nasty problem for everyone at their school. I admire the book’s emphasis on kids’ agency and cleverness — adults don’t solve the problems here, kids do — but the resulting story is hard to believe. Essentially, Goerz has taken up an Edwardian thriller, in which the blackmailer gets his just desserts at the point of a revolver, combined it with familiar middle-grade tropes about the excitement and anxiety of a budding friendship, and then tried to engineer a nonviolent, affirming, and progressive payoff. I didn’t quite buy it. The Shirley and Jamila books recast the Holmes and Watson relationship with two middle-grade girls, the White, Anglo-Canadian Shirley Bones and the Pakistani Canadian Jamila Waheed. Goerz portrays contemporary Toronto as a welcoming multiethnic community and promotes an ethic of inclusivity and diversity. The first book, Shirley & Jamila Save Their Summer (2020), is about a theft, but the thieves turn out to be relatable and redeemable characters, and the book becomes a paean to tolerance and understanding. This second book, however, has an out and out villain, one who isn’t quite humanized and certainly not redeemed. He is, tellingly, a rich White boy who epitomizes privilege. This villain seeks to hide his insecurity by gathering secrets, blackmailing his classmates, and turning them against each other. Masking his aggression with smarm and false concern, he is an abhorrent character, loathsome through and through. Of course, Goerz can’t have him shot at point-blank range, à la Conan Doyle, but she has to defang him somehow. This is where the book’s secondary plot about friendship comes in, as a new friend of Jamila’s becomes the means of his undoing. In essence, Goerz introduces a new character into Jamila and Shirley’s friendship dyad, testing their connection to each other, while trying to convert Conan Doyle’s tale of a blackmail victim’s revenge into something more positive. Along the way, the story skirts moral complexity, justifying questionable decisions made by Shirley and Jamila in the pursuit of justice. The original Conan Doyle story endorses vigilantism (key to Holmes's appeal) and excuses Holmes’s deceptive tactics, spying, and use of disguise and feigned friendship in the name of a higher good; these same moves look strange when committed by a fifth-grader. Again, I didn’t buy it. So, I have my doubts about recasting Holmes and Watson, originally 19th-century British men of fortune, as contemporary school kids in a progressive milieu. This second book stirs up those doubts. Its plot-rigging is, again, hard for me to believe, and the Jamila/Shirley relationship isn’t helped by Shirley’s Holmesian habits of secrecy and spying. The resulting mix is unsteady, with Goerz working hard to foreground Jamila's perspective but Shirley upstaging Jamila with her eccentric, Holmes-like brilliance and cool scheming. That said, this is a briskly cartooned, inventively laid-out graphic novel, more visually dynamic than its predecessor. The story’s highlight is the extended, multi-chapter burglary carried out by Shirley and Jamila, a sort of tightly wound heist sequence that takes up a good 90 pages. This is exciting stuff, a tense, precisely staged caper (I imagine that Goerz relished the challenge of staging it). I have to admit, I expected more serious moral repercussions afterward, and I’m disappointed that Goerz didn’t push the hard questions, but there are some nice, suspenseful moments along the way. I hope Goerz will do further Shirley and Jamila books, though I also hope that she doesn’t pattern their stories so closely after Conan Doyle — her characters and milieu seem to call for something else.

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed