|

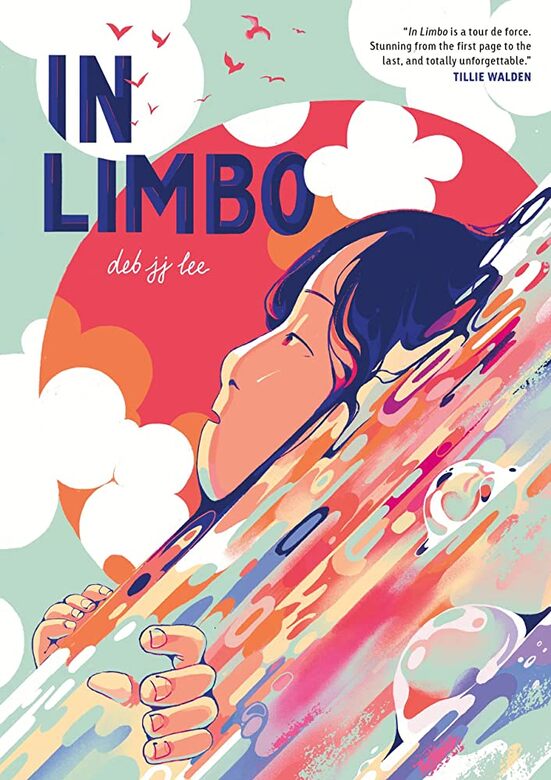

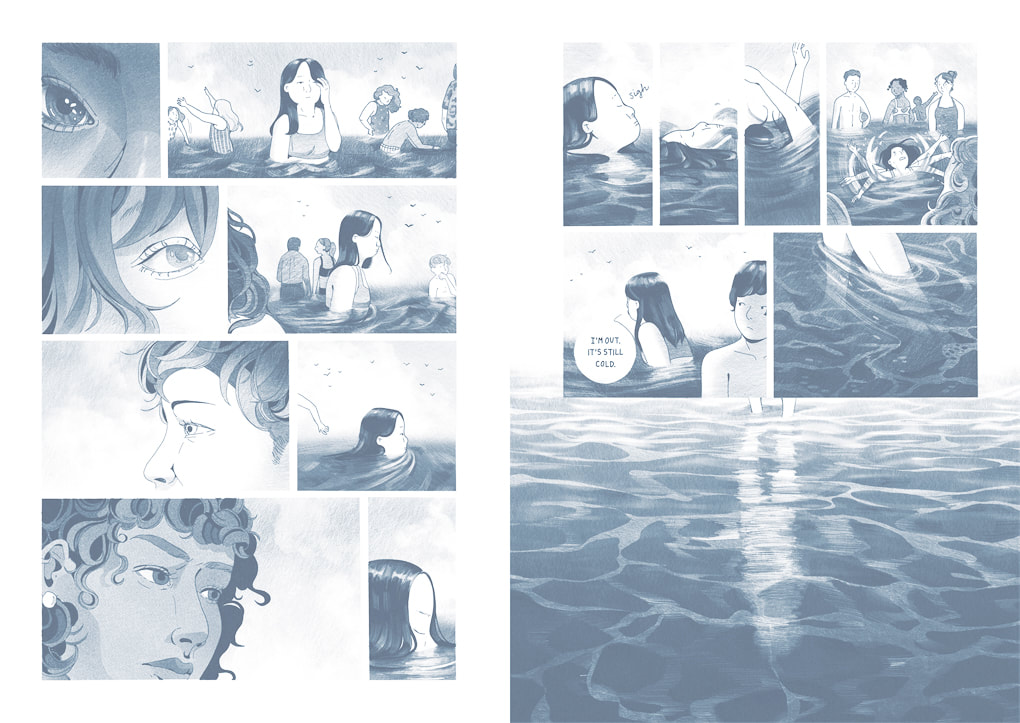

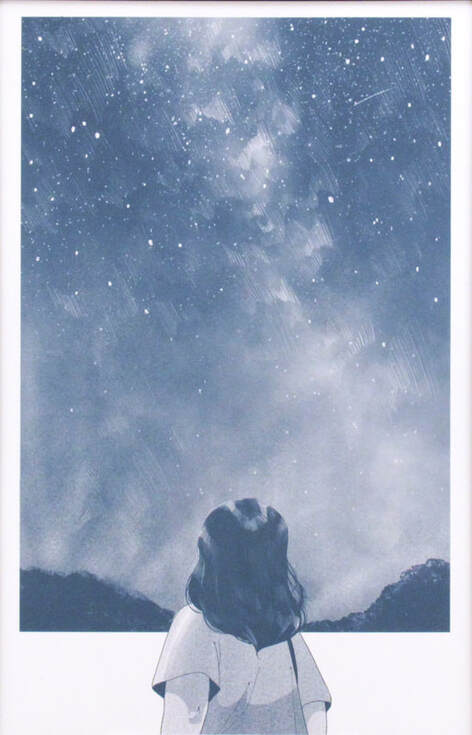

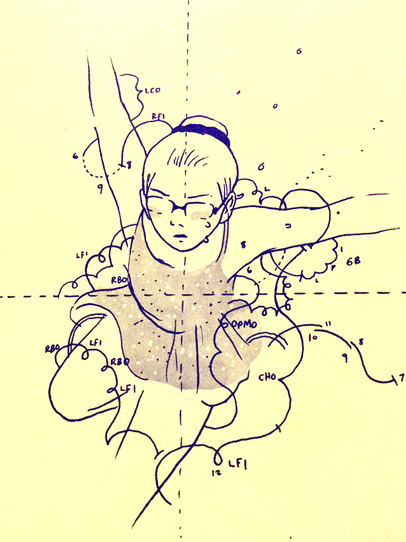

In Limbo. By Deb JJ Lee. First Second, ISBN 978-1250252661, 2023. US$17.99. 352 pages, softcover. I lost sleep over In Limbo. Foolishly, I started to read it late one night, when I was in a sticky, sort of unhappy mood that had nothing to do with the book and much to do with work. I needed to read something that was utterly different than the work I was obsessing over; I needed a way out of my spiraling. So, I thought I would start In Limbo before bed. Just start it, you know? Get my feet wet. But no — once I started, I had to finish. Damn. There was something quietly harrowing about the book, something that frustrated and gnawed at me. I think maybe I was angry with the book's protagonist, and her mother? Or maybe bothered by the evocations of racism, bullying, or depression? Struck by the contrast between the book's elegant, quiet style and its dark undertow? Whatever it was that got to me, I felt pretty helpless about it. I mean, I did put the book down for a few minutes, about a third of the way in, but then I grabbed it up again, anxiously, and plowed on. As the story got deeper and darker, I was all in. When I finished, it was well after midnight — and of course I had the story on my mind as I tried to get some shuteye. Again, damn. In Limbo is a graceful and refined graphic book, a beautiful feat of design, and a moody, enveloping story. It's also observant and brave. Thematically, the book treads some familiar ground: a high school memoir; a Korean immigrant's story; an exploration of familial tensions, crushed friendships, cultural in-betweenness, mental and emotional fragility, suicidal thoughts. The protagonist is a version of author Deb JJ Lee, and the story tracks her four years of high school, leading up to graduation and college after a long spell of desperation and loneliness. Okay, none of that feels unprecedented. But In Limbo is bothersome and riveting, a tough, involving work. I couldn't read it complacently. It pulled me in with its long silences, layered, emotionally telling details, fraught conversations, and occasional shocks. Its cloudy, blue-grey palette, monochrome yet somehow endlessly varied, feels soft, yet Lee uses it to create sharp, crisply defined pages — despite their refusal of black frame lines and their frequent use of bleeds. (Note that in life the author goes by they, but the book genders Deb as she, which, Lee says, more accurately reflects who they thought they were in high school.) Their layouts are often dense and maximally detailed, yet the overall impression is dreamlike, entranced. At first blush, it looks like a book that should be calm. But calm is not what the book is about, and reading it often hurts. What I'm trying to say is, this is a great and hard book. Briefly, In Limbo follows Deborah (Jung-Jin), or Deb, through her four years of high school as she tries to love and understand herself, embrace art as her vocation, and get out from under her family's expectations, especially the relentless needling of her very driven, at times abusive, mother. Her mom, as a character, hews perilously close to the "tiger mom" stereotype (as the book itself acknowledges). Their relationship is full of jagged edges and cruel scenes — and it's one of the things, I think, that caused me to read on, after midnight, in hopes of relief or understanding. Deb's father and brother don't register as strongly; In Limbo is very much a daughter/mother story. Yet it's also about friendships, sometimes fraught, overburdened ones. Deb's feelings for her friend Quinn, to whom she has a sort of desperate, proprietary attachment, lead to surprising reversals. Officially, In Limbo is described as "a cross section of the Korean-American diaspora and mental health," and that seems right, but it is Lee's depiction of complicated, ambivalent relationships that yields the greatest shocks. Lee doesn't show young Deborah as a good friend; instead, they show her taking friends for granted, or reading them strictly through the lens of her own anxiety, or laying terrible responsibilities on them. In this sense, the book seems self-accusatory. Deb doesn't understand what she's doing, of course, and the story is partly about her coming to grips with how she hurts both her friends and herself. Some relationships outlive the end of the book, others don't, but the book is remarkably generous in the home stretch, as Deb opens out from the tortured inwardness of the first half and learns to see more clearly. To say that the book's characterizations are complex would be a measly understatement. In Limbo doesn't resolve every problem it raises. This is probably partly by design; Lee has acknowledged in interviews (again, see this one) that their life, past and present, is more complex than a single book can cover, and the book seems anxious to show Deborah as a work always in progress. There are things in the book I'd have liked to know more about. Some relationships and threads are still nagging me, even now. Some readers may finish the book wanting to know more about Lee's understanding of internalized racism and the pressure to assimilate. Some may wonder about the connection between those things and the book's tormented mother/daughter dyad (cf. Robin Ha's graphic memoir Almost American Girl). Some readers may be anxious to know more about the mother's abuse, what prompts it, and how Deb lives with it (cf. Lee's own short comic from 2019, "Dear CPS," readable on their website). Some may wish that the Künstlerroman aspect of the book came through more strongly, that they were left knowing more about Deb's artistic vocation. Some may wonder about Deb's implicit queerness or perhaps about gender nonconformity. I've been thinking about all those questions; the book feels a bit tentative about what to include, what to leave out, and how to balance things. That said, I don't expect complete "closure" in memoir, and when I do get it, I worry that I'm being sold a bill of goods. In Limbo has honesty and emotional rawness despite its delicately finished surface, and I dig that. That "surface" is going to draw in and mesmerize a lot of readers, I expect. The book's rapturous reception has a lot to do with Lee's virtuosity as an illustrator and designer (indeed, the many blurbs on the cover note their lush, meticulous art). In Limbo is visually extraordinary; the book is gorgeous and transporting, a master class in narrative drawing and sustained mood. That mood is melancholy almost the whole way through, but In Limbo is vital and ravishing enough to make one fall in love with melancholy. (My images here don't do the book justice.) I'm grateful to this book for introducing me to a singular and gutsy artist. Most highly recommended: another high watermark for autobiographical comics about adolescence. <3

0 Comments

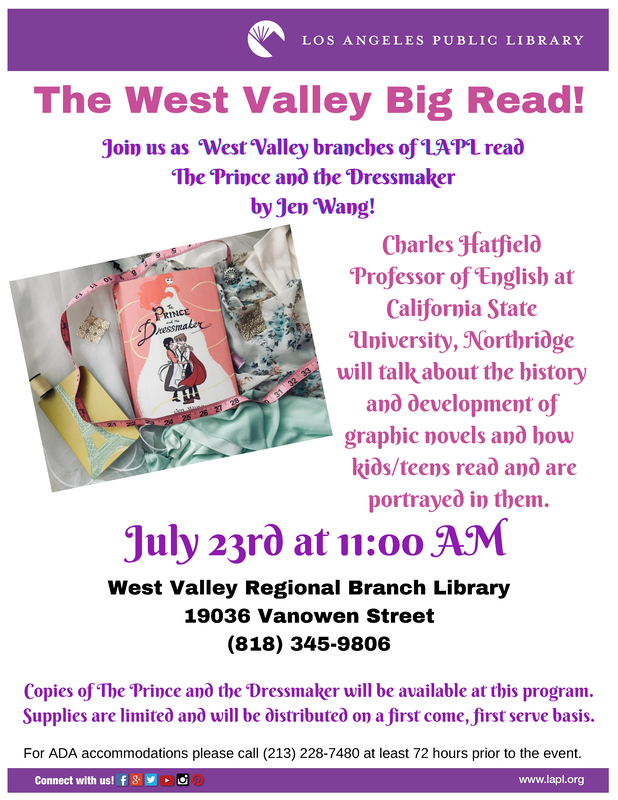

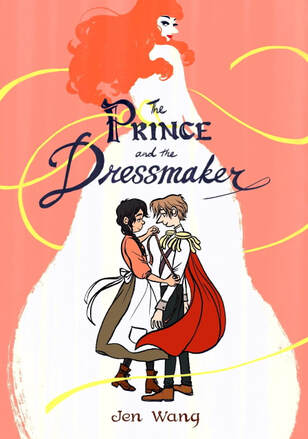

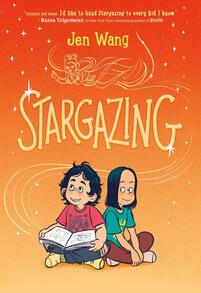

I'm honored and delighted to be giving a talk as part of the Los Angeles Public Library's West Valley Big Read focusing on Jen Wang's graphic novel, The Prince and the Dressmaker (the first book I ever reviewed here on KinderComics). Jen Wang is one of my favorite cartoonists, and The Prince and the Dressmaker one of my favorite books of the 2010s. In fact, I'd say it's one of my top ten graphic novels of the past half-decade. So doing this talk is a real treat! As the above flyer says, the talk is happening at the West Valley Regional Branch Library on Saturday, July 23, at 11:00 a.m. LAPL has more information about the talk here: https://www.lapl.org/whats-on/events/lets-talk-graphic-novels. Readers, I hope some of you will be able to make it — and please help spread the word!

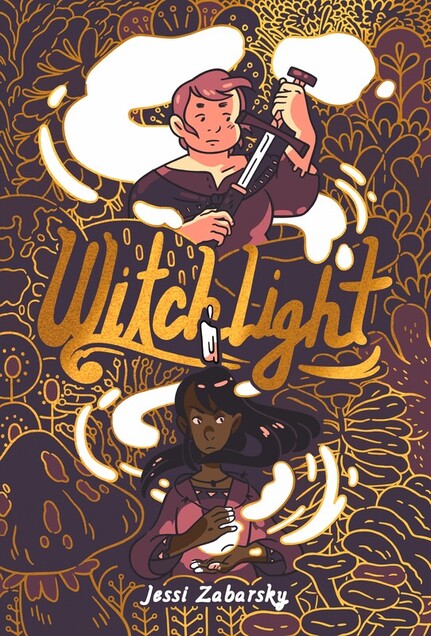

Witchlight. By Jessi Zabarsky. With coloring by Geov Chouteau. RH Graphic/Random House, 2020. ISBN 978-0593119990, $US16.99. 208 pages. I guess you say that this review is part of an occasional series (heh). In an unnamed land—a marvelous, culturally syncretic fantasy world—two young women undertake a magical quest and, as they go, learn how to care for one another. One of them, Lelek, volatile and enigmatic, is a witch who has lost half her soul. The other, her newfound friend (well, at first her kidnappee) Sanja, is determined to help find it. Love blooms between them—a matter of blushing shyness at first, but then owned and enjoyed with a winning matter-of-factness. As they travel, Lelek and Sanja scare up money by challenging local witches to duels, but often end up learning from those same witches; their travels uncover woman-centered communities and hints of matriarchal lore and magic. The larger culture hints at witch-hunting and misogyny, and this leads to a harrowing twist in the final act, but also, by roundabout means, to the resolution of a mystery and a ringing affirmation of Lelek, Sanja, and everyone they’ve befriended en route. Originally published by Kevin Czap’s micro-press Czap Books in 2016, Jessi Zabarsky’s Witchlight is a gorgeous and soulful feast of cartooning in a clear-line but vigorous, rounded style (which reminds me a bit of Czap’s own). It grows more confident in its linework and layouts as it goes. Beautifully colored by Geov Chouteau, the pages sing with an assured minimalism and harmony. I suppose the backstory and conflicts could be established more firmly—the plot might be clearer—but on the other hand, I enjoyed immediately diving back into the book to better understand its dreamlike premises. The book’s feminist, antiracist, and queer-positive ethos are a part of that dream and arise organically from the world Zabarsky has created; she uses her secondary world to imagine a better one. The utopian vibe is complicated by emotional and social nuances and an earned sense of loss and struggle. More than anything, Witchlight radiates a sense of love, offhand intimacy, and the thrills of self-discovery. Zabarsky clearly delights in her characters. She is a great cartoonist, with another graphic novel promised from RH Graphic by year’s end. I can't wait!

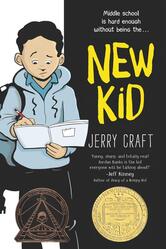

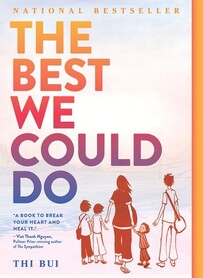

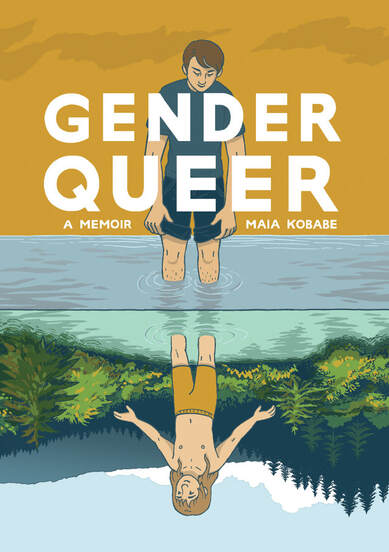

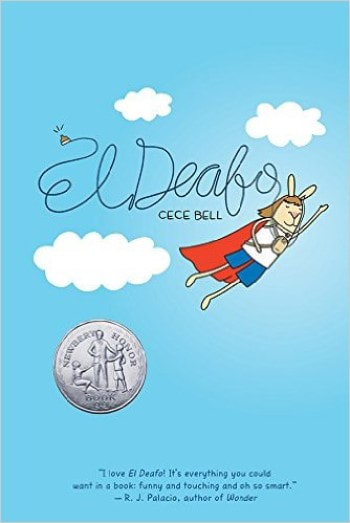

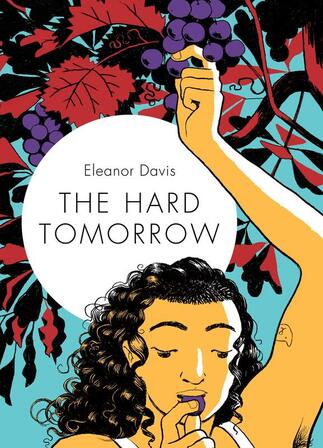

A partial list, forever in progress (every week I learn about new stuff)!(This Election Week post grew out of queries from colleagues as well as virtual teach-ins at CSU Northridge. It is very much a quick, tentative dispatch!) Below is a bunch of notes, roughly organized, about comics (especially graphic novels) that engage urgent social issues such as voting, migrant and refugee experience, racism, police violence, political activism, gender, feminism, and LGBTQ+ activism. Note that not all of these books are designated as children's or young adult books, and many contain frankly adult content. OTOH, there are some excellent young reader's books here. Besides long-form comics like graphic novels, other, shorter comics may engage such issues too, webcomics in particular. Webcomics are typically free and often address vital issues briefly and powerfully; e.g., consider the many affecting comics about living under COVID (see especially the series “In/Vulnerable,” on thenib.com, researched by reporters for The Center for Investigative Reporting and drawn by Thi Bui: https://thenib.com/in-vulnerable/). The Movement for Black Lives and the Black Comics Explosion  March, by the late John Lewis, with collaborators Andrew Aydin and Nate Powell — a memoir trilogy about Lewis’s participation in the Civil Rights Movement. One of the most acclaimed of recent American comics, and highly recommended. “Your Black Friend,” by Ben Passmore, a short satirical comic found in his book Your Black Friend and Other Strangers. Also, see Passmore’s collaboration with Ezra Claytan Daniels, BTTM FDRS, an urban horror story and satire about gentrification—it’s gross and very good! (I’d check out anything by Passmore, though he may not appeal to everyone, and some of his more underground-like work is a mixed bag. He has a new graphic novel called Sports Is Hell that I haven’t read yet. Be sure to look for Passmore’s online comics, especially on The Nib. He often engages issues of police violence and critically engages the BLM movement.) Damian Duffy and John Jennings adapted Octavia Butler’s classic novel Kindred into a graphic novel: a heartfelt piece of work about time-traveling back into the era of slavery. They have recently adapted another of Butler’s novels, Parable of the Sower, but I haven’t read it yet. Speaking of Jennings, he and fellow artist Stacey Robinson together drew the graphic novel I Am Alphonso Jones, written by Tony Medina—the story of a young Black man killed by police. This is often categorized as YA. Hot Comb, by Ebony Flowers, combines memoir and fiction: a series of short, intimate stories, many exploring the consequences of racist beauty standards for Black women. Understated, powerful. Sometimes also categorized as YA. See Jerry Craft’s New Kid for a funny, insightful middle-grade GN about being a scholarship kid of color in a tony private school. (Craft has a new book, Class Act, that I haven’t read yet.) Bitter Root, by Chuck Brown, David Walker, and Sanford Greene, is an ongoing comic book series that filters period pulp action through African American historical and cultural lenses. There are two collected volumes so far. It’s overtly political even as it dishes out monster-smashing action: an Ethno-Gothic, steampunk, antiracist adventure. Cool. (Not understated!) Great African American SF/fantasy novelists like Nalo Hopkinson, Nnedi Okorafor, and N.K. Jemisin have been writing superhero comic book serials lately. Jemisin is about 2/3 of the way through a Green Lantern series with many topical elements titled Far Sector, drawn by Jamal Campbell. It concerns race and the challenge of living in a pluralistic society (a faraway world inhabited by billions of beings of several different species). Smart, rich work. Immigrant and Refugee Experience Alberto Ledesma shares reflections from his life as an undocumented immigrant in Diary of a Reluctant Dreamer, a very personal scrapbook of sorts that grew out of a series of Facebook posts. Eye-opening for me, and poignant. Besides superheroes, Nnedi Okorafor has written a SF comic called LaGuardia that deals with immigration and nativist backlash—but on a planetary level! It’s drawn by Tana Ford. Escaping Wars and Waves, by graphic journalist Olivier Kugler, depicts Syrian refugees living in refugee camps, and is excellent. Border: A Crisis in Graphic Detail, edited by Mauricio Alberto Cordero, is a recent comics anthology about migrant experience at the US’s southern border, and a fundraiser for the South Texas Human Rights Center. Powerful stories and testimony. The Scar, by Andrea Ferraris and Renato Chiocca, is a brief but powerful treatment of the US/Mexico border. Migrant: Stories of Hope and Resilience, written by Jeffry Korgan and illustrated by Kevin Pyle, recounts personal stories of crossing the US border (I haven’t had a chance to read it yet). Thi Bui’s graphic memoir, The Best We Could Do, about five generations in the life of a Vietnamese American family, is brilliant, a great book. (Matt Huynh’s webcomic Cabramatta resonates with this: http://believermag.com/cabramatta/. So does GB Tran's book Vietnamerica.) The recent YA graphic memoir by Robin Ha, Almost American Girl, depicts a Korean American experience that perhaps invites comparison. There are quite a few graphic memoirs about the experience of immigrants’ children—see, e.g., I Was Their American Dream, by Malaka Gharib. They Called Us Enemy, by George Takei, Justin Eisinger, Steven Scott, and Harmony Becker, is an autobiographical account of the incarceration of Japanese Americans during WW2. Much to learn here. Immigration policy is discussed in Open Borders: The Science and Ethics of Immigration, by Bryan Caplan and Zack Weinersmith, though I haven’t gotten to read it yet. It’s a didactic graphic book: less story than argument. But there are many great comics like that! Comics on the Political ProcessUnfit: How to Fix Our Broken Democracy, by Daniel Newman and George O’Connor—though I’m afraid I haven’t read this yet. Drawing the Vote: An Illustrated Guide to Voting in America, by Tommy Jenkins and Kati Lacker. Comics about Indigenous LivesFor comics by Indigenous creators, see for example the anthology Moonshot, and check out publisher Native Realities: https://redplanetbooksncomics.com/collections/native-realities. In particular, the collaborations of artist Weshoyot Alvitre and writer Lee Francis IV (e.g., Sixkiller; Ghost River: The Fall and Rise of the Conestoga) have captured my attention. Look also for the anthology Deer Woman, co-edited by Alvitre and Elizabeth LaPensée. A recent scholarly collection, Graphic Indigeneity, ed. Aldama, will help here. Celebrated comics journalist Joe Sacco (who produces one stunning book after another) has just recently published Paying the Land, a book about resource extraction and energy politics, but most particularly the history of an Indigenous Canadian people, the Dene. I’ve read only the opening chapter so far (which is remarkable) but the book looks ambitious and informative. Know that Sacco is not an Indigenous author (he is Maltese-American), and scholar colleagues versed in this area have shared some eye-opening critical points with me; still, Paying the Land will surely be worth your time. Gender and Sexuality (Feminist, Queer, and Trans Perspectives)Drawing Power, edited by Diane Noomin, is a stunning anthology of stories about sexual violence, harassment, and survival. Strong, stinging, varied work there, sometimes harrrowing—a response to #MeToo. Maia Kobabe’s nonbinary memoir, Gender Queer, is tender and revelatory. You could call it a YA book, though of course its reception in YA circles has been fraught. (It's a frank depiction of, among other things, gender expression and sexual exploration — so, well, let's just say that some Amazon customers disapprove.) Look for the LGBTQIA anthology Love Is Love, a 2017 benefit to help victims of the Orlando nightclub shooting—short comics, but often powerful, and varied in approach. Justin Hall’s No Straight Lines: Four Decades of Queer Comics is essential history. Edie Fake's Gaylord Phoenix is a mind-altering, phantasmagorical quest fantasy from a trans perspective: a mostly wordless transition fable that rewrote the way I think about comics! Highly recommended. (Be aware: this is not tagged as a young reader's book, and includes startling images of violence and self-harm as well as sexual abandon.) Disability, Graphic Medicine, and CareCheck out the graphic medicine movement, devoted to comics treatment of illness, wellness, and dis/ability: see https://www.graphicmedicine.org. Note also the prevalence of disability memoirs in comics that are not medical in focus, e.g. Cece Bell’s great children’s comic, El Deafo; or the very recent (fictionalized) YA book, The Dark Matter of Mona Starr, by Laura Lee Gulledge, about depression; or any number of webcomics about life on the autism spectrum. Kabi Nagata’s manga My Lesbian Experience with Loneliness concerns not only sexuality but also anxiety and depression. Allie Brosh’s work also addresses depression and anxiety (Hyperbole and a Half; Solutions and Other Problems). Katie Greene’s Lighter Than My Shadow depicts her life with anorexia and an eating disorder. I highly recommend Vivian Chong and Georgia Webber's collaborative memoir, Dancing after TEN, which recounts a life-changing medical crisis for Chong that robbed her of sight; as well as Webber's own solo book about literally losing her voice, Dumb. Re: aging and elder care, see such graphic memoirs as Roz Chast’s Can't We Talk about Something More Pleasant? and Joyce Farmer’s Special Exits. Just a random recommendationFor depiction of progressive activism in a near-future dystopia, basically just a few steps from our own, read The Hard Tomorrow, by Eleanor Davis. This one rattled me, and it's beautiful. One last note (preaching to the choir?)As many KinderComics readers may know, children’s and young adult graphic novels are the fastest-growing, most robust sector of comics publishing in the US. They often deal with complex immigrant or minority experience, and offer queer-positive portrayals as well. Check out anything by Mariko Tamaki, Jillian Tamaki, Jen Wang, or Tillie Walden. This publishing movement is really doing bold new things in queer representation and identity narrative.

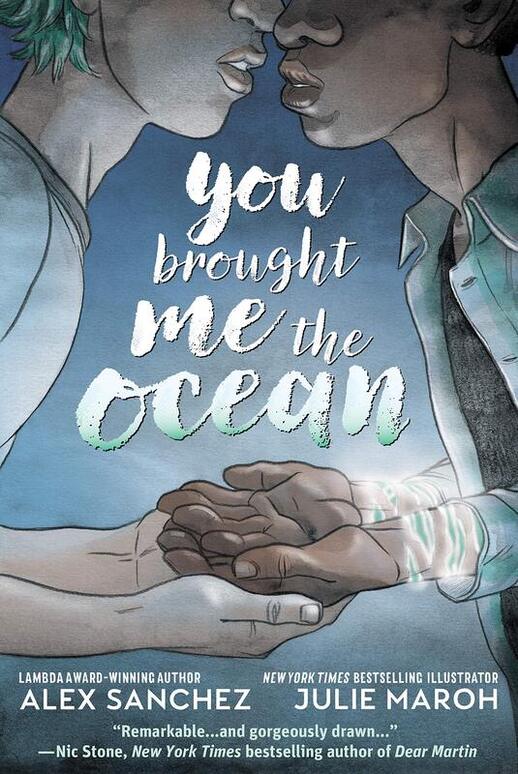

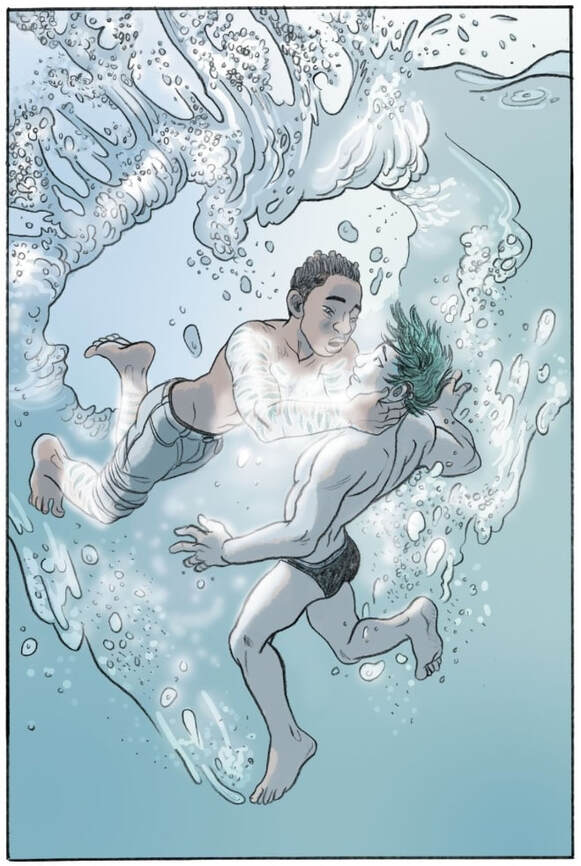

I have not been a fan of 21st-century DC Comics. Often I have criticized DC for not acting like a real publisher and for pushing more of the same ugly, self-defeating work: grim heroes, continuity porn, line-wide reboots, and other rigged and desperate moves. But nonetheless I found myself reeling from this week’s news of massive layoffs and restructuring at DC, part of a general purge at WarnerMedia (Heidi MacDonald has the best think piece on this that I’ve seen, over at The Beat). That was hard news. With DC losing a reported one-fifth of its editorial staff—indeed, as MacDonald says, “almost an entire level of editorial executives“—and the company’s publishing plans downsized, this seems like a fraught moment for comic-book culture here in the USA. I have to imagine that it’s a heartbreaking moment for many; the human cost of this sweep is considerable. It’s hard to know what to expect of DC going forward, though. Can we perhaps read some silver lining into this storm cloud? Interestingly, DC editorial will be run by two women (for the first time ever?), Marie Javins and Michelle Wells, the latter the head of DC’s Young Reader division. And, as MacDonald speculates, it seems likely that “DC’s kids and YA books will be more important going forward.” I take that as good news—but I’m afraid the news for direct-market comic book shops doesn’t sound so good (see my recent reflection on that subject here). DC Publisher Jim Lee, who remains in place after the layoffs, gave an interview to The Hollywood Reporter last Friday that puts a bright face on the changes; it seems intended to be reassuring. But I’m not reassured. (See Heidi MacDonald and Rob Salkowitz for informed readings of that interview.) I am, however, guardedly impressed by DC’s current Young Adult line, despite initial skepticism and misgivings about the work continuing to be work-for-hire in the traditional DC way. This brings me to (forgive me for pivoting so sharply) a happy review of a newish book: You Brought Me the Ocean. By Alex Sanchez and Julie Maroh. Lettered by Deron Bennett. Edited by Sara Miller. DC Comics, ISBN 978-1401290818 (softcover), 2020. US$16.99. 208 pages. (BTW, this is the third in an occasional series reviewing children’s and Young Adult graphic novels from DC. See the first here and the second here.) You Brought Me the Ocean is a smart, beautifully rendered queer YA romance in the guise of a superhero origin story, and a whole, rounded novel to boot. Despite being set in a desert town, it’s about water, about the ocean, and about learning to live as an “amphibian” in a mostly dry world. There’s something about Aquaman in it, and Superman does a distant fly-by, but, really, this story belongs to young Jake Hyde, his lifelong friend and neighbor Maria Mendez, and the young swimmer Jake falls in love with, Kenny Liu. (Jake is basically a new take on the Young Justice version of Aqualad, for those keeping track.) Kenny opens new doors in Jake’s life, just as Jake has to contemplate leaving home for college and a complex shift in his relationship with Maria. Fittingly named, Jake Hyde is closeted in several ways—in fact he is an unknown even to himself—but the story represents his coming out and coming into his own, folding together hero-origin tropes with high school and romance conventions. Loved ones and bullies alike exhibit homophobia—but, with the exception of one foul thug, the major characters all reveal unexpected depths and changeability. Characters disappoint, but then happily surprise. As Jake realizes his powers—the reason for the strange, scar-like markings on his skin—he, Maria, and Kenny become a triad of friends, and the denouement is wish-fulfilling but not pat. (There could and should be a sequel.) If Ocean revisits some familiar stuff—protective or disapproving parents, homophobic bullies repping toxic white masculinity—its characters are distinct and nuanced, and have humanizing touches. Further, the familiar stuff feels pretty convincing: these aren’t cliches so much as things that commonly happen and should be acknowledged. The book has a confident sense of its characters from the first; I can believe, for example, that Maria and Jake are longtime friends, with a shared history and personal language. Their interaction feels real enough. Scriptwriter Alex Sanchez (Lambda Award-winning author of the Rainbow Boys trilogy) handles characters and world deftly, with a smart, unforced touch. And artist Julie Maroh (Blue Is the Warmest Color) seems to know these characters’ physicality—their carriage and body language—as well as an artist could. Maroh’s figures are compact, sensual, and expressive. Most importantly, they are distinct. You Brought Me the Ocean benefits from a unified aesthetic that is unusual for DC Comics. Bathed in watery blue and silver-gray, and then again in muted desert browns and tans, the book enacts the major conflict in Jake’s life through its very palette. Thanks to Maroh and designer Amie Brockway-Metcalf, it boasts a visual wholeness and integrity that set it apart. Subtle yet dynamic layouts, unhurried pacing, and mostly understated action define the book, which sidesteps epic superhero dust-ups in favor of smaller, though still dramatic, discoveries. That said, the art remains ravishing; Maroh’s individualized figures and muted colors cast a spell even as they do the vital work of characterization. This appears to have been a harmonious, lovingly edited collaboration; it’s a remarkable feat for a first-time team. As I said, I’d read more. You Brought Me the Ocean is YA superheroics done with grace and a sensuous visual language. In fact, it’s only a superhero story on its edges; fluency in the DC Universe is not required. At heart, it’s an affirming story of love and friendship with a fantastical, magic-realist touch. Recommended! PS. KinderComics is taking a roughly six week-long break, sigh, so that I can start the new semester at CSU Northridge more or less sanely. See you in about a month and a half!

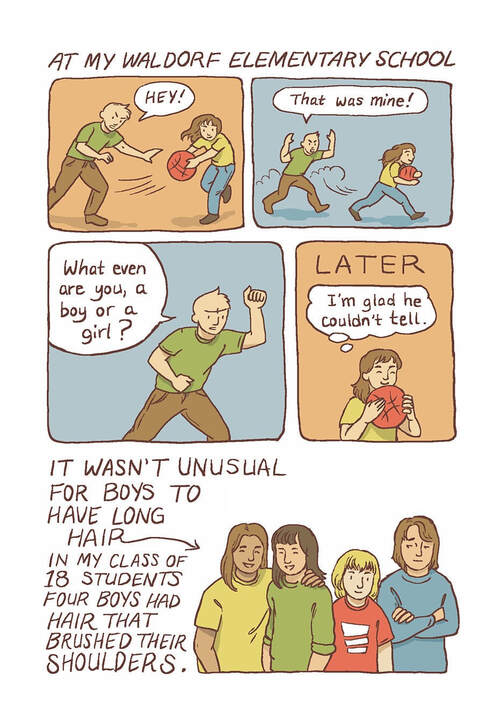

Gender Queer. By Maia Kobabe. Colors by Phoebe Kobabe. Sensitivity read by Melanie Gillman. Oni Press, ISBN 978-1549304002 (softcover), May 2019. $17.99. 240 pages. Glad to get to this one, at last. Gender Queer bills itself (on its cover) as both a memoir and a guide. It does both well. As a memoir, it is intimate, recounting a personal story about the push-pull of body and mind, self and society. It is as candid as it must be, as discreet as it can be. This is Maia Kobabe’s story, told with autographic frankness. As a guide, it gestures beyond the personal, giving an authoritative (though not universalizing) perspective on gender dysphoria, asexuality, and the politics of being a nonbinary subject in a binary culture. Actually, it works well as a guide because it works as a story — meaning Gender Queer is authoritative because Kobabe lived it. The book demonstrates how comics, by interweaving picture, word, and symbol, can evoke the general through the particular; how graphic memoir can do the work of political as well as autobiographical witness. Gender Queer credibly witnesses to tough issues precisely because Kobabe does not assume that anyone else has lived with those issues in precisely the same way; that is, the book honors the specificities of eir life (Kobabe uses the Spivak pronouns e, eir, and em). The quirks of eir own experience make the book what it is—yet sharing those quirks brings a vivid honesty that will speak to readers whose circumstances are very different from the author’s. Gender Queer is bookended by scenes of teaching and learning. In the opening, Maia struggles with eir autobiographical cartooning class, taught by MariNaomi (part of eir Comics MFA at the California College of the Arts); e resists the idea of sharing eir “secrets” on the page. Overcoming that resistance is prerequisite to the very book we are reading, and Kobabe depicts eirself tearing away a kind of veil to share eir story with us. In the closing, Maia teaches eir own comics workshop to tweens and teens at a local library, but struggles again: e reproaches eirself for not coming out to eir students, that is, not sharing eir nonbinary identity and preferred pronouns. Oddly, then, this coming-out story ends with an instance of not coming out, and of self-blame. The book is open about troubles and misgivings of this sort, as well as the familial and social awkwardness of negotiating new pronouns. In one striking scene, Maia’s aunt, a lesbian and committed feminist, responds to the pronoun question by challenging Maia’s perspective on FTM transitioning and genderqueerness, suggesting that these things may stem from misogyny, from a “deeply internalized hatred of women” (195). Maia is troubled by this challenge, of course, but the scene plays out with a delicate touch (eir aunt is properly supportive, not an adversary). Thus Kobabe is able to field a sensitive question, perhaps even to defuse the likely skepticism of some readers. I confess that these admissions of awkwardness and trouble swayed me; it was good to see Kobabe dealing with the struggles of family and friends without rancor or caricature. Gender Queer is that kind of book: humanly complicated, and willing to lean into complexity and trouble (it pairs well with L. Nichols’s Flocks in that regard). As an autographic, testimonial comic, Gender Queer adds to the fund of helpful cultural resources available to queer and gender-nonconforming young people. At the same time, it testifies to how Kobabe has drawn upon cultural resources in eir own journey: books, comics, Waldorf schooling, homeschooling, and art teachers (two depicted here, MariNaomi and Melanie Gillman, are queer cartoonists themselves). In Maia’s quest for self-understanding, books loom large: e is a voracious and self-documenting reader, a lister of books read and re-read. Kobabe’s account suggests that storytellers such as Neil Gaiman, Tamora Pierce, and Clamp served eir as resources for self-fashioning. A now-poignant passage recounts how Maia, a delayed reader at age eleven, taught eirself to read so as to devour the Harry Potter books (the irony of which, at the present moment, cuts like a knife). At a key moment late in Gender Queer, Kobabe turns to another book, neurophilosopher Patricia Churchland’s Touching a Nerve: The Self as Brain (2013), and even conjures Churchland as a character, an expert witness whose testimony about “the masculinizing of the brain” affirms Maia’s sense that “I was born this way.” This flourish is perhaps a touch too triumphant: Kobabe gives no sense of the intellectual debate around Churchland’s ideas, but simply invokes her as a bookish authority and solution. In any case, Gender Queer is, through and through, the record of a reader’s life. Style-wise, Gender Queer favors spareness and economy. Scenic backgrounds are few, and deliberate; Kobabe’s panels often consist of head shots against color fields. Conversation, reflection, and expression are everything. Pages typically follow a grid, whether unvarying or, more often, a bit relaxed, letting the white of the page show through: On the other hand, Kobabe lets rapturous, full-page drawing take over every so often. Clearly, eir minimalism is a considered choice, as confirmed by certain passages that break with the general sparseness. Dig for example these two facing pages: Though Gender Queer is discursive and text-filled, it never feels clotted. Kobabe’s organic hand-lettering and use of unbordered elements give the art breathing room. The pages include telling pauses, open bleeds, and dialogic exchanges that add up to a accessible, even brisk, read. Disarming is a good word for Gender Queer: the book’s honesty about dysphoria and bodily phobias may trouble some readers. I myself started the book in, admittedly, a guarded or hard-hearted mood, skeptical of the family ethos depicted: the utopian, back-to-the-woods values, the homeschooling, every little thing that I could interpret as a sign of sheltering or self-indulgence. Of course I was being pigheaded, and wrong — as the book’s warmth and complexity so clearly showed me. Gender Queer is moving and informative, an invaluable memoir and guide.

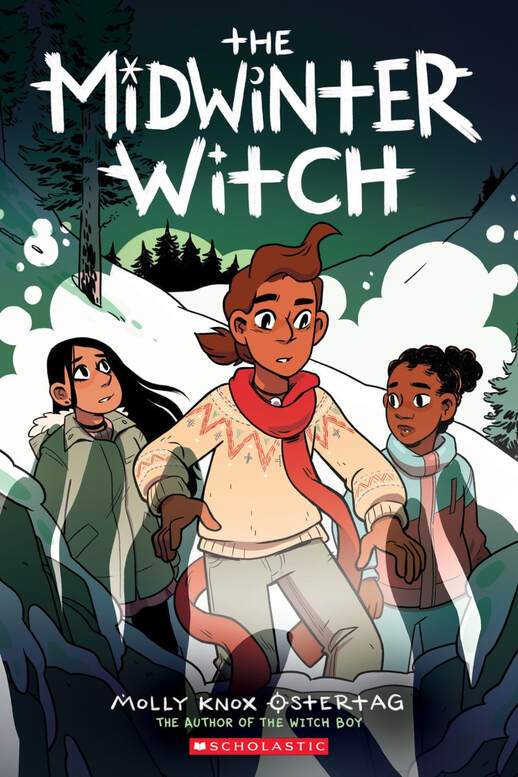

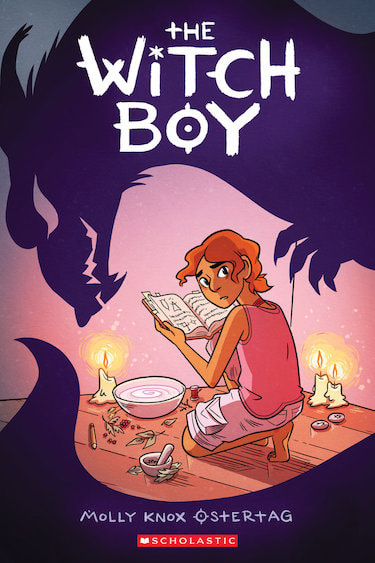

Coming-of-age stories about young witches have definitely become a genre in young readers’ graphic novels: a means of blending fantasy and Bildungsroman, and of telling stories about gender and sexuality, sometimes about other forms of difference, and about resistance versus conformism. Generally, these witch stories offer gender-conscious, often queer-positive, fables of identity. Post-Harry Potter, but often rejecting the Potter novels’ emphasis on passing in the mundane world, they also seem influenced by Hayao Miyazaki and the magical girl franchises of anime and manga. Here are reviews of three graphic novels about witches that came out, one after another, last fall: The Okay Witch. By Emma Steinkeller. Aladdin/Simon & Schuster, ISBN 978-1534431454 (softcover), Sept. 2019. 272 pages, $12.99. A girl named Moth, a misfit in her Salem-like town, discovers that she comes from a line of superhuman witches, her mother is more than three centuries old, and her family is entangled in the history of the town and its witch-hunters. Moth’s grandmother has retreated into a timeless, otherworldly utopia for witches, while her Mom has embraced the mortal world and sworn off witchcraft. Grandmother and Mom argue over Moth’s destiny, while Moth seeks her own way. There’s an intriguing story hook in this middle-grade fantasy, which poses an ethical dilemma about retreating from, versus engaging, an imperfect world — and suggests an allegory of America, in which women of color (Moth and family) expose and challenge the culture’s white-supremacist and patriarchal origins (the witch-hunters). However, The Okay Witch seems tentative and underthought, hobbled by blunt exposition, shallow characterization, and patchy drawing. Steinkellner’s characters are designedly cute and expressive (her style reminds me of Steenz), and she seems to grow into the work as she goes, but the results are unsteady. The breakdowns and staging of action sometimes confuse, the settings lack texture and depth, image and text do not always cooperate, and distractions such as crowded lettering and jumbled perspectives dilute the impact. The novel is progressive, hopeful, and charming, much more than the pastiche of Kiki’s Delivery Service suggested by its cover, but still strikes me as a derivative, uncertain effort. Mooncakes. By Wendy Xu and Suzanne Walker. Lettered by Joamette Gil; edited by Hazel Newlevant. Roar/Lion Forge, ISBN 978-1549303043 (softcover), Oct. 2019. 256 pages, $14.99. Mooncakes is a Young Adult fantasy about witches, werewolves, and demons, set in a world where magic is — well, not commonplace, but not unheard of either. More than that, it’s a gentle romance between two sometime childhood friends, now young adults: Nova, a witch who lives and works with her grandmothers (also witches); and Tam, a genderqueer werewolf and a refugee, running from cultists who seek to exploit their power. Even more, though, Mooncakes is a paean to community: a culturally diverse, queer one that helps Nova and Tam bind demons and face down their adversaries. The complicated plot hints at a world in which the relationships between technology and magic, humans and spirits, and the living and dead could take volumes to explore. Xu’s drawing is organic and expressive, her pages lively variations on the grid, with occasional dramatic breakouts. The settings are richly textured, the colors thick, a tad cloying. The emotional dynamics are enriched with grace notes of characterization (Xu and Walker know when to take their time). That Nova is hard of hearing is a point gracefully handled, neither central nor incidental. The story is finally a bit too pat, and reworks some shopworn elements — again, there’s that whiff of Miyazaki, with animal spirits and talk of a young witch’s apprenticeship. Yet the distinct characters and budding romance make it click. The Midwinter Witch. By Molly Knox Ostertag. Color by Ostertag and Maarta Laiho; designed by Ostertag and Phil Falco. Scholastic/Graphix, ISBN 978-1338540550 (softcover), Nov. 2019. 208 pages, $12.99. The Midwinter Witch rounds out Ostertag’s middle-grade Witch Boy trilogy — though I dearly wish this wasn’t the last book, since she has created such a beguiling world and winning family of characters. The series keeps getting better, and this volume hints at conflicts and potential that could sustain even deeper explorations. Here, Aster (the gender-nonconforming “witch boy”) and Ariel (a character introduced in the second book, The Hidden Witch) and their friends attend the Midwinter Festival, a yearly reunion of Asher’s extended family. There they compete in a tournament that requires each of them to face their fears: Aster’s of defying a strictly gendered tradition, Ariel’s of not fitting in, of being the orphan and odd witch out. Acerbic and defensive, Ariel is not sure she can become part of Asher’s very welcoming family. A dark force from her past looms up, luring her to a different path and leading to a confrontation that is all too quickly resolved — I wanted to know more about Ariel’s particular darkness and its source. The payoff, though, is lovely and affirming. The Midwinter Witch is a remarkably sure-handed work of cartooning, enlivened by deft, often silent, characterization, artfully designed pages that mix the grid with bleeds and multilayered spreads, and felicitous coloring. Overall, it’s a marvel of elegant, empathetic storytelling — a new high for Ostertag. By way of conclusion, I invite KinderComics readers with insights into this genre to weigh in with comments! I'd love to hear from readers with a strong interest in this kind of story; I'm eager to gain a fuller sense of the witch's tale, where it comes from, and what it might mean for culture and for comics. I see literary, cinematic, and anime/manga influences in this genre, but still find myself wondering, why is the witch's tale flourishing now, as a comics genre? How does the treatment of the witch's tale in comics differ from its treatment in prose?

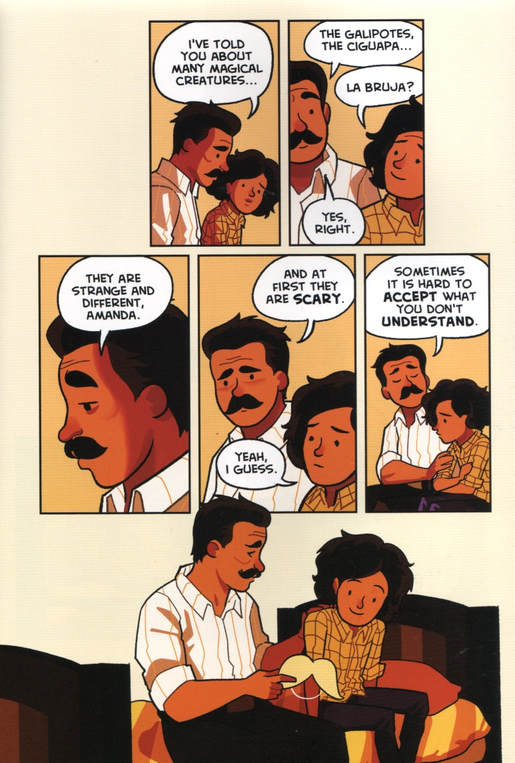

The Cardboard Kingdom. By Chad Sell, with Vid Alliger, Manuel Betancourt, Michael Cole, David Demeo, Jay Fuller, Cloud Jacobs, Kris Moore, Molly Muldoon, Barbara Perez Marquez, and Katie Schenkel. Alfred A. Knopf/Random House Children’s Books, June 2018. ISBN 978-1524719371. Hardcover, 288 pages, $20.99. The Cardboard Kingdom celebrates community and in fact is the work of a community: a team made up of cartoonist and creator Chad Sell and ten co-writers, referred to by the publisher as “new and diverse authors” (one of whom, Kris Moore, sadly seems to have passed away). An impressive collaborative feat, it depicts an idealized neighborhood of kids who also collaborate, turning their everyday lives into, basically, a nonstop live-action roleplaying game. A paean to shared creative play—essentially, the book is about kids as cosplayers, crafters, and friends—it must also have been a playful, if complicated, project. Happily, everything clicks. The book works as an anthology of short stories and vignettes, from about five to thirty-plus pages in length, but more powerfully as a novel, which, though episodic, designedly builds to a big and satisfying finish. Sell enlisted each author to write a story or two, and then apparently brought them together to cook up the boffo finale. Reading it straight through, it’s almost seamless; the novel builds its neighborhood carefully, gradually introducing new characters into its busy communal scenes. Though the publisher says The Cardboard Kingdom is about “sixteen kids,” I counted nineteen distinct, recurring child characters in the novel, some identified only by their roleplaying names, some known by more than one name. There’s a lot of juggling going on, but never to the point of distraction. The publisher also says that the book depicts “adolescent identity-searching and emotional growth”—yet it certainly isn’t YA fiction. My sense is that The Cardboard Kingdom is emphatically a middle-grade novel, aiming for upper elementary to perhaps middle school age. While its large cast, complex rigging, and lively and dynamic pages say “middle-grade” to me (not younger), its eager, almost ingratiating cartoon style reminds me of Pixar—say, Inside Out, with its mix of emotional gravity and toylike cuteness. Certainly the book depicts identity-searching and emotional growth; however, its bright cartooning, winsome children, and almost Peanuts-like sense of suburbia (not wholly idyllic like Schulz’s but still reassuringly safe) seem pre-adolescent in tone. Its let’s-pretend and DIY ethos brings back some early memories of my own. I mention this not because I’m concerned about age levels (KinderComics doesn’t usually focus on leveling) but because I’m interested in The Cardboard Kingdom’s treatment of identity, which I consider bold for a middle-grade novel. If graphically the book suggests years of reading Peanuts and Tintin, its imagined neighborhood has a utopian queer- and trans-positive vibe that would make it a good companion to, say, Alex Gino’s groundbreaking George (also a middle-grade fiction). Among the book’s young role-players are several who defy or ignore gender norms. In fact the first story, “The Sorceress,” written with Jay Fuller, introduces a cross-dressing pair: the titular Sorceress, soon shown to be (ostensibly) a boy but only much later identified as “Jack,” and his neighbor, a seeming girl who refuses the princess role and becomes The Knight (I don’t think she ever gets another name). Reportedly, this story was the kernel or inspiration for the whole book. There’s more: one character, Sophie, defies expectations of sweet girlishness and becomes a rampaging, Hulk-like bruiser she calls The Big Banshee; another, Amanda, a self-styled Mad Scientist, worries her father by wearing a mustache. Meanwhile, the relationship between Miguel the Rogue and Nate the Prince hints at a young gay crush. The Cardboard Kingdom, in fact, resists conventional gender and sexual roles throughout. For all that, it’s a story about kids who like to imagine combat: big, frenzied dust-ups between heroes and villains. Reading it, I was more than once reminded of an Avengers movie. If the drawing style and solid, bright colors follow a clear-line aesthetic, recalling the moral and ideological sureties of so many children’s comics, then Jack Kirby is surely a reference point too, from the Big Banshee’s unabashed monstrousness (more cheerful than tragic here) to the outrageous costuming, replete with spiky cardboard headgear that would do Cate Blanchett proud. The book taps the same vein of explosive fantasy that superhero comics do, but with more charm than most. The neighborhood kids of The Cardboard Kingdom, though they never really hurt one another, like to run around and fight; Sell and company are unafraid of children’s capacity to play at physical conflict and violence. Further, many of the kids like to be “bad guys” as well as “good,” and the book gleefully mines that tendency for humor. There’s a disarming mixture of sweetness and brutal imaginings in the book, though it all comes out seeming like harmless fun. Sell and his collaborators have a feel for the reckless, revved-up fantasy lives of young kids hanging out together--I appreciate that. And no adult ever dictates the terms of, or reins in, what the kids are fantasizing about. The book presents an entirely child-driven and child-centered world of cooperative, if pugnacious, play. In short, it’s feisty as well as sweet. Behind its bright, cheery surface, then, The Cardboard Kingdom is structurally tricky and thematically gutsy. On the critical side, I would say that some of its component stories resolve too quickly; the book runs the risk of being too neat, because its nested structure and sheer number of characters demand fast pacing, even when dealing with hard matters of identity and parent-child tension. Problems are invoked and solved with speed. In that sense, it’s, again, utopian. Also, the book makes some obvious, even heavy-handed, didactic moves, though in the direction of adult chaperones rather than child readers. Its sharpest lessons will likely be ones of forbearance and acceptance aimed at concerned parents whose children are behaving, well, unexpectedly. The best examples of parenting in The Cardboard Kingdom involve suspending or tempering judgment, i.e. being brave about children’s imaginative self-fashioning (would that all anxious parents course-corrected as readily as those in the book). But, most of all, it’s the book’s wise embrace of childhood play that makes The Cardboard Kingdom a brave and interesting graphic novel, one I highly recommend. Random House provided a review copy of this book.

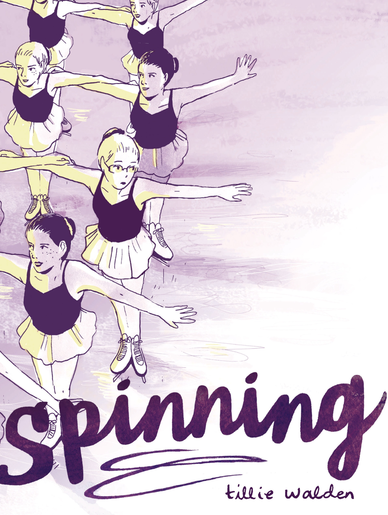

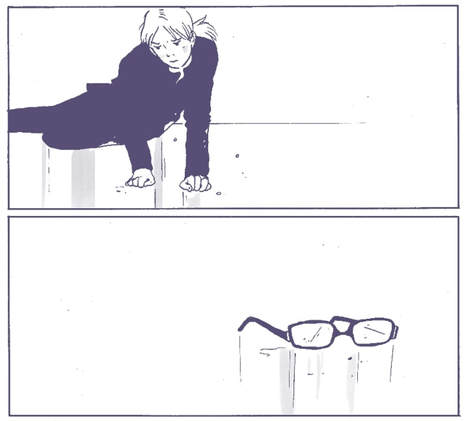

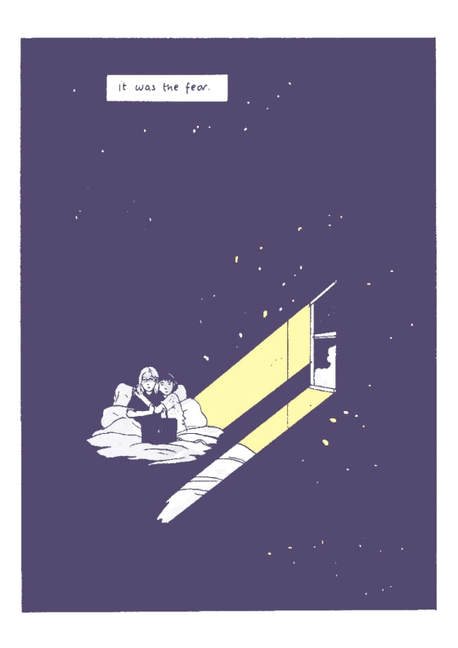

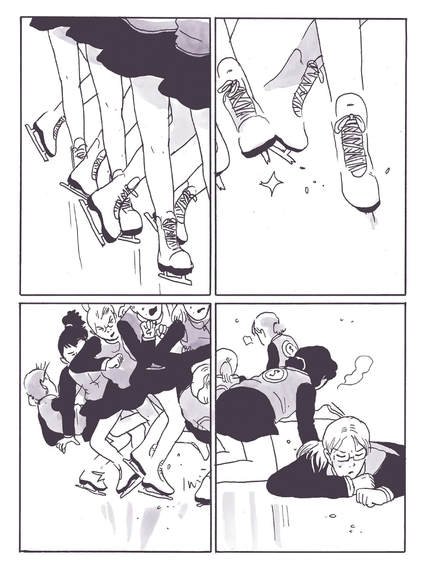

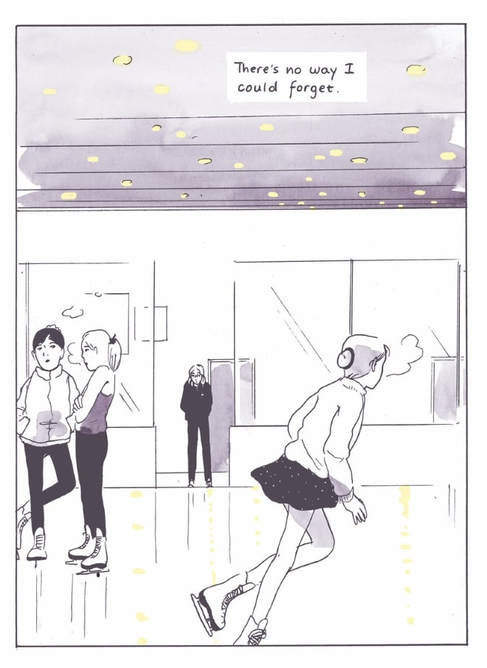

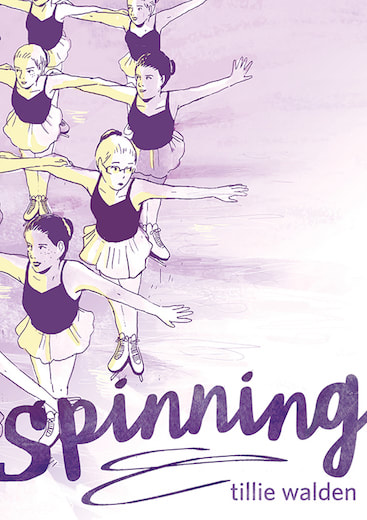

Spinning. By Tillie Walden. First Second, 2017. ISBN 978-1626729407. $17.99, 400 pages. Nominated for a 2018 Excellence in Graphic Literature Award. The feeling of waiting curbside for a ride in the predawn cold, watching headlights sweep through the darkness. Of peering out windows on sleepy car rides. Of early-morning arrival at the ice rink. Of locker rooms, benches, and earbuds, of lacing up your ice skates, everyone in their own little orbit, quietly, tensely readying themselves. Of being the new girl, of being sized up to see if you are “a threat.” Of skating across the ice, jumping and falling, your eyeglasses flinging off and away. The feeling of a teacher’s hands on your shoulders, helping you on with your jacket, and the inward recognition that you are gay. Of sidelong glances in a classroom, “dizzy” with longing. Of walking in a crowd of girls, talking about Twilight (Edward or Jacob?), while hiding who you are. Of playing “never have I ever” with the girls while hiding who you are. Of passing. Of trying to recreate, as a skater, with your body, the “tiny graphs and charts,” the “intricate patterns and minute details,” of an instruction book. Of desperately holding hands during a synchro skating routine. Even as the speed is “ripping them apart.” Holding on for dear life. Of friendship as a lifeline. As rivalry and sympathy intermingled. The feeling of being judged, as your teammate speeds up to walk a few paces ahead of you. Of winning and losing, of exulting in first place and weeping when you lose. Of knowing that you cannot always be the one that wins. The tears of your competitors, and your own. The dread of the school bully, rendered faceless in memory but still so powerfully there. Your hands nervously playing in your lap, or gripping your knees. Your teacher questioning you. The feeling of falling asleep next to your brother by the light of a laptop screen. Of crying from the makeup in your eyes. Of pulling a blanket up over your head. The sight of the girl you like stretching, and quietly smiling at you. The feeling of being alone with her. Of love, bounded by fear. Of kissing: I didn’t know it would feel like that. Of capering in a hotel room, alone, free from anyone’s judgment. Gazing into your reflection in the surface of a vending machine. The felt “eternity” of a three-minute skating routine. Feet in the air, in mid-jump. Stares and glances. Stares and glances. Girlhood as competitive arena. The feeling of being tested, and failing. Of being alone in a closed room with a tutor who treats you as a thing. The memory of his hand. The feeling of coming out, in a broad, silent room crossed by a slanting beam of sunlight, your mother huddled, tense. Of coming out to your music teacher, in a loving embrace. The sensation of drawing. Of time collapsed into drawing. Of a skate remembered as a nervous, tight grid of panels. Of moves and thoughts flickering. Of falling. Oh my god / my coach is looking at me / the audience shit / the judges The sight of oncoming headlights like round staring eyes. The memory of his hand. Of quitting skating. Walking away.

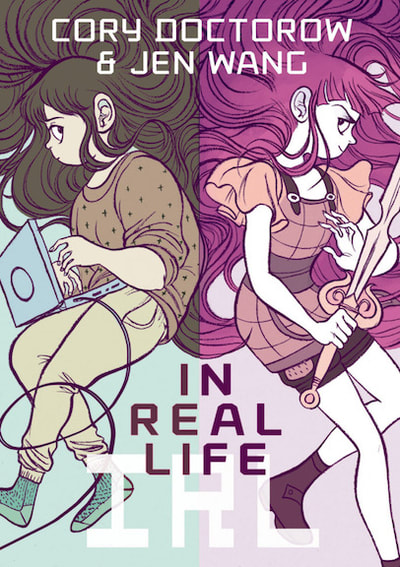

Driving away, crying. Of returning to the rink, once more, just to prove that you can leave. (There’s no way I could forget.) For all these experiences, and many more--so finely observed, so precisely caught, in a style at once tense and graceful, minimal yet conveying every telling detail, rigorous and yet so light and free—for all this, Tillie Walden’s memoir Spinning is an unforgettable comic, the kind that gets inside your mind and heart. I cannot recommend it highly enough. WOW. No sooner do I finish reviewing Jen Wang's splendid new graphic novel, The Prince and the Dressmaker, than I realize that Wang and a panel of other great talents will be discussing the book at Chevalier's Books, Los Angeles's fabled independent bookstore, tomorrow night, Thursday, March 15, at 7:00pm. The details are at Chevalier's site, here (Chevalier's is at 126 North Larchmont Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90004). Wang, author of Koko Be Good (2010), co-author, with Cory Doctorow, of In Real Life (2014), and co-founder of the Comic Arts LA festival, will be joined by Doctorow, as well as two other notable comics creators, Molly Knox Ostertag and Tillie Walden. Doctorow is of course a novelist (author of Little Brother among others), columnist, tech expert and activist, and the co-editor of Boing Boing. Ostertag is the author of the recent graphic novel The Witch Boy (whose exploration of gender resonates with The Prince and the Dressmaker), co-creator of the graphic novel Shattered Warrior, and co-creator of the ongoing webcomic Strong Female Protagonist. Walden is author of the recent graphic memoir Spinning (one of 2017's most acclaimed comics) and the webcomic (soon to be graphic novel) On a Sunbeam, as well as the graphic books The End of Summer, I Love This Part, and A City Inside. This is an incredible gathering of talent. Frankly, it would be hard to imagine a stronger panel than this when it comes to the intersection of children's publishing and graphic novels, small-press and independent comics, women comics creators, and explorations of gender and sexuality in comics. I dearly hope to make this event, which I expect is going to be great!

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed