|

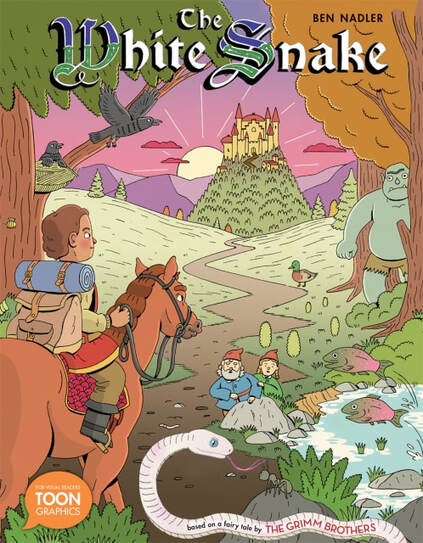

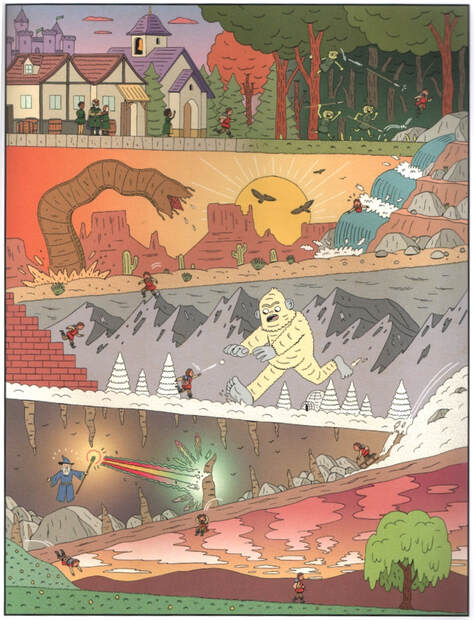

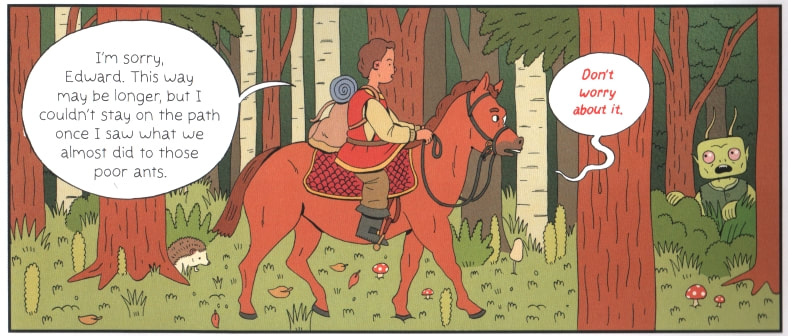

The White Snake. By Ben Nadler; based on a fairy tale by the Grimm Brothers. Edited by Paul Karasik and Dashiell Spiegelman; book design by Françoise Mouly. TOON Books, 2019. ISBN 978-1-943145-37-9 (hardcover), $16.95 ; ISBN 978-1-943145-38-6 (softcover), $9.99. 56 pages. Matter-of-fact inventiveness, marginal drollery, and a heaping helping of weirdness are the main ingredients of Ben Nadler's The White Snake, a winningly eccentric update of a Grimm Brothers fairy tale. It's a cool book. The story is about the getting of wisdom through acts of eating—literally, by taking bites of things. Its logic is less literal than symbolic, a matter of telling parallels and a neat sense of karmic payback: its hero helps various creatures who then help him in return, making it possible for him to overcome various trials. In a sense, the hero wins out because he listens and because he cares—he has a compassionate feeling toward the world around him. This helps when he is set impossible tasks that must end in either victory or death. The upshot of those tasks is that our hero must compete to win the hand of, you guessed it, a princess—but Nadler takes pains to update the tale so that the princess is no shrinking violet, but a smart leader who helps set things in motion in the first place. They become a team, and she the ruler of the land. The story ends with enlightenment (a blast of cosmic insight) and a not-too-crazy happily-ever-after that melds fairy-tale logic with progressive values. The fated parallels and connections so typical of Grimm fairy tales are preserved, the unselfconscious strangeness of folktales maintained, even as the book weaves in current feminist and environmentalist concerns. This is a considered adaptation, helped quite a bit, I gather, by the editorial input of Paul Karasik and TOON's Françoise Mouly. The results are wise as well as cool. The book’s visual style is sharp and clean, almost aseptic, with pristine lines that suggest a yen for the Ligne Claire tradition. Yet at the same time there’s an anxious, post-punk quality that, for me, recalls Mark Beyer or Henrik Drescher, and a trace of eccentric gothicists like Edward Gorey and Richard Sala. Lane Smith’s early, Klee-like work comes to mind too—also Adventure Time, and perhaps Klasky Csupo animation. Which is to say that Nadler’s mark-making, though spare, retains some nervous tics; his pages, though restrained in layout and admirably clear, hint at art-comics affinities. The look here is less the Ivan Brunetti-esque schematic minimalism of Nadler's self-published risograph comic Sonder (in which bodies tend to be clean, geometric forms) and closer to the illustrative lushness of his first book, Heretics! (a graphic history of modern philosophy, co-created with his father, philosopher Steven Nadler). But we are still a long way from naturalism here. The characters are a bit stiff, as opposed to supple; faces are schematized; action is coolly posed. The frequently oblong, page-wide panels tend to stage events and travels as if they were happening in front of a scrolling panorama. The total look implies both stability and an unrepentant oddness—well suited for the blithe absurdity of the story and its deadpan embrace of the weird. Along the way, Nadler enlivens the pages with a wealth of curious detail. There’s a great deal of whimsical chicken fat, and odd critters abound. Right from the start, you can tell that Nadler intends to draw out and reward attentive readers with all sorts of sidelong business. The result is a distinct and pleasurable graphic world, crawling with fun stuff. Like Jaime Hernandez's The Dragon Slayer (another folklore-inspired TOON Graphic "for middle grade visual readers," i.e. experienced comics readers), The White Snake is less a solo act than a group effort. It appears to have been carefully curated by TOON's editorial director Mouly and guided by input from editor Karasik, who supplies the educational back matter: a brief essay on folktales, including a frank discussion of how the book has adapted and revised the Grimms' version. All this contextualizes the book without interfering with its story or damping down its quirkiness. The result is delightfully odd—another TOON title yoking together children's literature and alt-comix aesthetics. It has put Ben Nadler on my radar, for which I'm grateful, and joins a growing smart set of folk and fairy tale-based comics. Recommended!

0 Comments

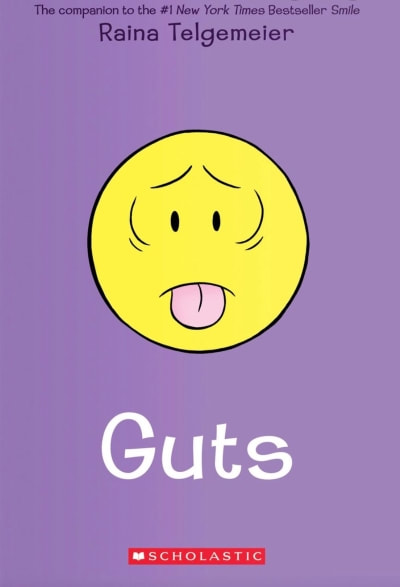

Guts. By Raina Telegemeier. Scholastic/Graphix. ISBN 978-0545852500 (softcover), $12.99. 224 pages. Raina Telgemeier is an engine, a star, a phenomenon. All of us who follow the world of graphic novels have heard this. For several years Telgemeier has borne a job description that, until recently, perhaps no one imagined we would ever need: America’s best-selling graphic novelist. Hype surrounds her like a halo (go, Raina!) Her success is proof of the graphic novel’s decisive new mainstreaming, and further proof, if any were needed, of the buying power and cultural clout of tweenage girls. She is, we’re told, “the Judy Blume of graphic novelists,” and her stardom has been a bellwether of the children’s graphic novel movement. Telgemeier’s publisher, Scholastic, has capitalized on all this with gusto, rolling out the red carpet for each new release and boosting Raina to million-copy print runs. Earlier this year, a spinoff product, Share Your Smile, a kind of “interactive journal,” signaled a new phase in the branding of Raina: an exhortation to her readers to write their own autobiographical stories in the vein of Telgemeier’s breakout books, Smile and Sisters. I honestly don’t know what to think of Share Your Smile, which seems more about design than revealing content: a guided activity book comparable to Wreck This Journal, The Diary of an Awesome Kid, and so many others. I suppose I had wanted to see something more reflective or essayistic, less about prompts and nearly-blank pages for readers to fill in. (It strikes me that young readers may get more from how-to cartooning books like James Sturm et al.’s Adventures in Cartooning or Ivan Brunetti’s Comics: Easy as ABC!) Telgemeier’s latest, though, Guts, now that’s a real book — and for me, her best. Guts is a middle-grade girlhood memoir akin to Smile and Sisters, and designed to match (Telgemeier’s autobiographical books and fictional books are distinguished by different design schemes). It’s in familiar Raina territory: a story of social awkwardness and anxiety, family and friendship, and the minute moral decisions and moments of confusion, defensiveness, and selfishness that can make school life so complicated. Predating the events of Smile, it depicts Raina, the author’s childhood self, going through fourth and fifth grade. Though it matches its sibling titles (indeed, Scholastic has just released all three in a boxed set), it stakes out its own thematic turf, revealing Raina’s anxieties and phobias in an emotionally charged way that goes a step further. It’s a brave book, and, I’m tempted to say, one that only a well-established children’s author could get away with. Guts depicts panic attacks and (as the title hints) upset stomach, cramping, and retching, as well as social and eating-related anxieties. It joins the considerable body of autobiographical comics that deal with anxiety, psychological distress, and neurodivergence. (Such themes are foundational to autographics as a genre, from Justin Green onward.) For a middle-grade graphic novel, Guts is, well, gutsy; it includes many scenes visualizing physical and psychological discomfort, and in some cases sharp pain and outright terror. It also includes quite a few scenes of bathrooming, bodily embarrassment, doctor’s office visits, and therapy sessions. “Treatment” is essential to its story. In short, Guts contributes to the graphic medicine movement. In the process, it yields the most harrowing and inventive pages Telgemeier has yet created. At the same time, Guts is very much a young reader’s book, never forgetting its main audience and taking care to explain and palliate the scary stuff—not with promises of quick cures and happy-ever-afters, but by showing that anxiety and panic are survivable and can be understood and, with practice, coped with and reduced. Young readers who dig Telgemeier’s books are likely to find Guts a warm, awkwardly funny, and ultimately reassuring guide. I tend to think that Telgemeier’s best books are her memoirs. Her fictional graphic novels to date, Drama and Ghosts, have been well-intentioned liberal fables with under-examined premises (Drama has been faulted for reproducing romantic stereotypes of the antebellum South, and Ghosts for naive cultural appropriation and whitewashing colonial history). Both have tried to do good things: Drama is a queer-positive, gender-defying romance, and Ghosts a story of family affected by illness and disability. But they aren’t tough-minded books, and Telgemeier doesn’t quite skirt the pitfalls built into their premises. In her memoirs, however, Telgemeier has crafted a believably human alter ego, just anxious and at times selfish enough to pose serious ethical dilemmas, and she has a way of disclosing certain hard things that don’t get solved, even as her boisterous cartooning conveys a bright, affirming outlook on life. The balance is exquisite, and Telgemeier usually nails it. Guts is the Raina book I’ve liked best. I will remember its formal gambits (startling for a middle-grade graphic novel) and its honesty. Telgemeier, at once a first-class storyteller and a commercial powerhouse, has clearly hit her stride. This book take chances, the chances pay off, and I’m impressed by the way she manages to walk the tightrope.

Below is a byline that I have cherished. No one wrote about the comics community and comics creators with the same mix of moral intelligence, goodwill, and improving sharpness than Tom Spurgeon, the famed Comics Reporter, who, to my very deep sorrow, has just passed away. Tom was free-minded and honest, by turns tolerant and critical as the occasion demanded. His BS detector was keen, but he wrote without spite. I've been edited by Tom (in the pages of The Comics Journal) and interviewed by Tom (at the Reporter) and lucky enough to spend a little, just a little, time with him over coffee or breakfast at the San Diego Comic-Con. He made time for that, for which I will always be grateful. Sadly, I have never yet been to Cartoon Crossroads Columbus (CXC), the comic art festival for which Tom served as Executive Director, and now I will never be able to see it with him. I didn't see him often enough, frankly. When I did, my world seemed a bit bigger and bit better. Tom had the gift of real magnanimity. He could argue and make points and dig for news without rancor or crude self-interest. His heart was that large. Tom would ask piercing questions, and in our conversations I was always aware that his mind was bent toward reporting, but I never had a conversation with him that made me feel smaller. I always felt boosted by his interest and kindness. Comics had no better ambassador: one who did the work without ever surrendering to smarm, false praise, or shallow, feel-good bromides. Tom's writing about comics creators and industry practices often stung with his moral insight; he made no apologies for what was ugly in comics, and again and again he stood up for those who make comics. Tom was tough-minded but gracious, with a genuine feel for people that had nothing to do with being ingratiating. And he could write in so many different ways. I found him a delightful mystery. I mean, he edited The Comics Journal, a magazine known for its critical ferocity, then went off to write the comic Wildwood (1999-2002) for cartoonist Dan Wright, a gentle, faith-filled strip about a rural church and its pastor, a quiet giant of a bear. He had studied in seminary before he became a writer. He dug up dirt, but also worked to bring people together. He could be razor-sharp and humanly decent at the same time. That he valued decency seemed to part of conscious working-out of things in his life. Tom had soul, and worked to sustain it. My god, he was something. I want to note here that when my colleagues and I were in the process of founding the Comics Studies Society, Tom was very interested in this. When we met up on several occasions, Tom asked me pointedly how the work of founding the CSS was going. He supported comics scholarship and asked smart questions about it, as I witnessed many times. For example, when the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum held its grand reopening festival in 2013, Tom and I were there, and I remember his unfeigned delight in the proceedings, his sense that comics study had found a grand new home. He loved it. I admired Tom's intellectual curiosity and farsightedness, qualities that I reckon made him perfect for the CXC job. The world of comics feels smaller tonight; Tom Spurgeon has gone. I hope that the US comics community will find ways to honor Tom that bring support back to the community and its struggling artists, something that would be in Tom's spirit. RIP to a great good person who made a great difference in my, and in so many, lives. Too soon gone, too soon gone: a bright shining light, now shuttered. I'm staring at this computer screen, lost, wondering what I can do. Tom, I'll never forget your example. My deepest condolences to all Tom's family, friends, colleagues, and loved ones, everywhere.

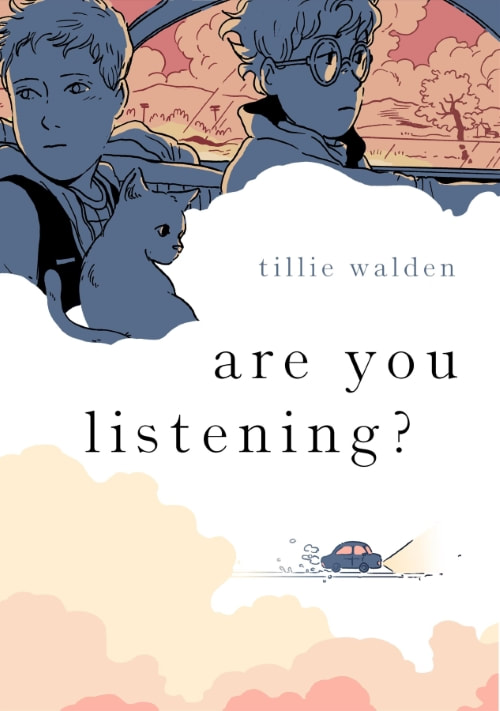

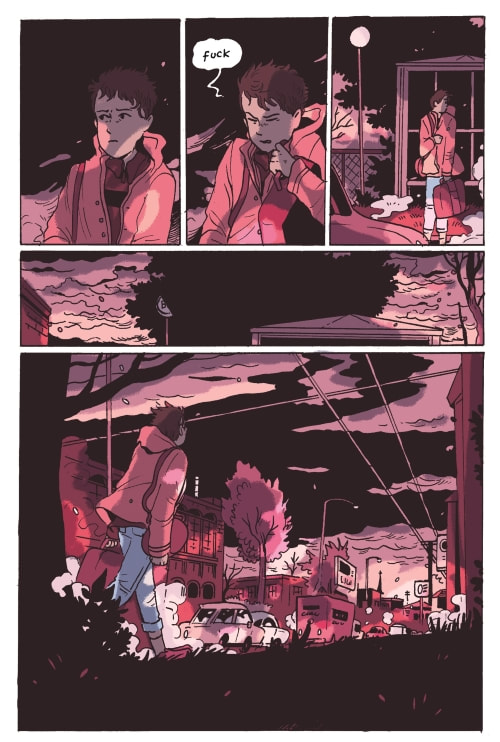

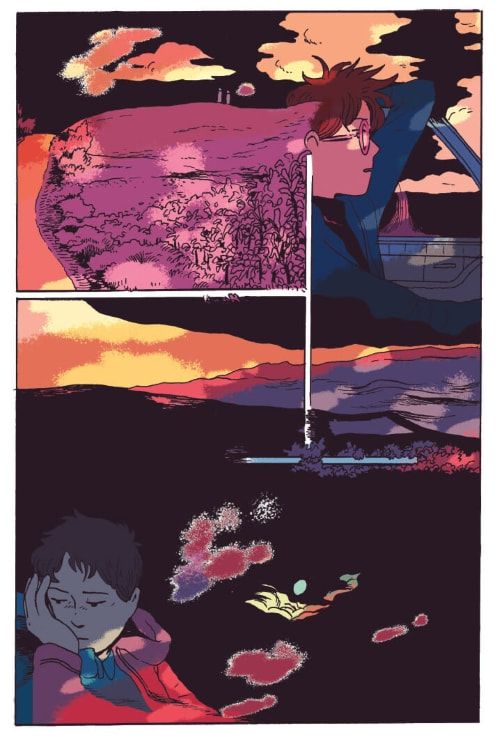

Are You Listening? By Tillie Walden. First Second. ISBN 978-1250207562 (softcover), $17.99; ISBN 978-1626727731 (hardcover), $24.99. 320 pages. Are You Listening? boasts colors unlike any I’ve seen in other comics. It blends and dapples contrasting colors in rapturous ways I literally haven’t seen before. And that heady palette is crucial to the transporting effect of the story: a dreamlike road trip, or wayward, puttering anti-quest, which eventually turns into something more intent and directed. On this odd, minimally detailed trip, the two protagonists, Bea and Lou, both young women with things to get away from, motor through a color-drenched mystic vision of west Texas landscape. They are pursued by indistinct and merely functional antagonists (less men than shadows). En route they find a cat, a perhaps-magical one, whose mysterious nature provides some shape and urgency to the trip. Logic is not the story’s strong point — but, oh, is this an easy book to love. Tillie Walden strikes again. One of Walden’s strengths is dialogue among women, especially young women. From prickly defensiveness to guarded care to unguarded tenderness, she traces the growing relationship between Bea(trice) and Lou, two queer fugitives whose friendship and love may remind readers of other tender pairings in Walden’s work. They are funny together, and sharp-edged enough that their growing bond feels earned rather than programmed. Just watching Lou teach Bea to drive is a pleasure. The dynamic between these two is the heart and soul of Are You Listening?. On the other hand, the book’s ventures into Miyazaki-esque fantasy are not worked out as thoroughly, or really worked out at all, on anything other than a symbolic level — which is to say that the story feels great but sort of collapses when you try to summarize it. Okay. Why do I still dig the book so much? It’s solidly in Walden territory, recalling the romantic dyads and love-motored plots of several of her earlier books, though without the rich social surroundings evoked in Spinning or On a Sunbeam. It’s perhaps a Thelma and Louise homage, crossed with the more elusive Miyazaki of films like Spirited Away or Howl’s Moving Castle, where a felt sense of symbolic fitness matters more than the literal working-out of plot-logic. At its heart are half-hidden losses and traumas that eventually come into the open, via revelations handled with a thankfully discreet touch: the terror that Bea is running from, the bereavement that has propelled Lou out onto the highways. Re-reading the book, you can see these things signaled early on, with moments of barely-quelled panic, ragged intakes of breath, creepy and confining interiors, and enigmatic, triggering exchanges. Walden has a gift for gnawing suspense as well as bruised tenderness, and Are You Listening? is a straight-up master class in how to pull readers into the minds of brave but anxious protagonists. The book invites trembling. That said, Are You Listening? isn’t Walden’s best-plotted book. Truth to tell, it’s the first one by her that has nudged me toward ambivalence — that is, toward some delicate balancing of swooning gratitude against the sense that something hasn’t quite worked. But, okay, I’ve grown fairly besotted with Walden's comics — meaning that I’ve fallen head over heels, in such a way that I doubt that I can render a dispassionate judgment. Who can blame me? Walden draws like anything: beneath the fragility of her line lies an unassuming confidence in form, an ability to draw just whatever she needs and ditch the rest. You’ll find here nary a trace of underdrawing, tentativeness, or fuss. My guess would be that she works as hard as hell to make her comics look like no work at all — that behind these beautiful pages is plenty of the usual agonizing effort of the comics artist. If that’s so, Walden hides it superbly; the images seem to have arisen spontaneously from some lovely Other Place. And her use of color? Damn. The coloring here, pressing on from what was already delicious in On a Sunbeam, makes a world. Most of all, though, what matters is the writing of character. Bea and Lou, like so many of Walden’s heroines, balance sweetness with strength and rawness with principle, revealing reserves of determination and agency when the story pushes them hard. They are worth rooting for. At the same time, Walden has the wisdom not to insist on affirmation and closure on every front — here, as in other books, she leaves you with a live wire of ache, even to the end. Walden has a gift for intimacy in the face of big things: quiet spaces amidst the panorama of unfurling landscape (west Texas, or, as in Sunbeam, deep space). This is her stock in trade: moments of reunion, reconciliation, and self-discovery against the backdrop of a huge, obscurely glimpsed world. On that score, Are You Listening? delivers in spades. Hell, I’ll read anything this artist does — she makes my eyes mist over.

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed