|

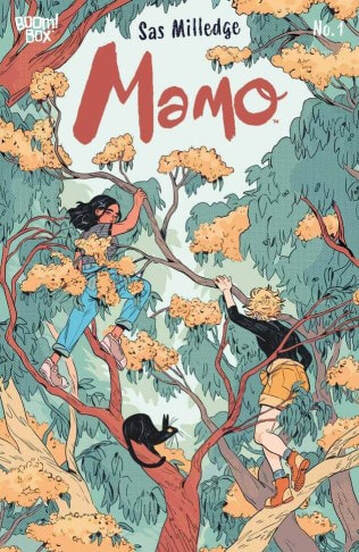

Mamo #1-3 (of 5?). By Sas Milledge. BOOM! Studios / BOOM! Box. July-September, 2021. $US 4.99 per issue. 44-56 pages each. I don't ordinarily review periodical comic books, in the sense of single issues aimed at the direct market, on KinderComics, especially when the stories are still in progress, but for Mamo I must make an exception. Sure, this fantasy about two young women sharing magic and solving problems together is yet another witch-themed story for young readers (of the type I've been covering lately, here, here, here, here, and here). Sure, its storyworld and its visuals are decidedly Miyazaki-esque, with particular nods, I think, to Miyazaki's versions of Kiki's Delivery Service and Howl's Moving Castle. Genre-wise, this has become familiar territory: I'm convinced that Hayao Miyazaki is the key to much of what is happening in contemporary fantasy comics (see for example my comments on Mark Siegel and company's 5 Worlds or Tillie Walden's Are You Listening?). I see many homages to his work even when attending small-press festivals. In that sense, Mamo is not new. But Melbourne-based artist Sas Milledge really delivers the goods here. This is a nuanced, breathtakingly beautiful story, with smart, insinuating characterization, a deliberate, thought-through, but not mechanical approach to magic, and a healthy respect for mystery, both the secrets of the heart and of the world. It really is something, and I can't wait to read it to the end. I won't go into detail here (I expect to come back to Mamo when it is collected), but, briefly, the story takes place in and around an agrarian village, a place that may coexist with the modern world yet seems firmly preindustrial and bucolic. The setting seems vaguely European, ambiguously Irish or Scandinavian or Nordic (with perhaps a nod to Finland's Tove Jansson). But the ambiguity may be important. Protagonist Joanna Manalo, or Jo, is a Filipina. Her co-protagonist, the book's leading witch, boasts an Irish name, Orla O'Reilly. Their village includes a variety of people. Jo and Orla's relationship is the mainspring of the plot: Jo enlists Orla's aid to counteract a seeming spell or curse that overlies the village. Orla's grandmother, the Mamo of the title, once served as the village witch but seems to have died, while yet leaving behind traces of herself that contain powerful and vexatious magic. Jo and Orla must travel round the village and environs to find spots haunted by Mamo, spots of weirdness and trouble that need to be calmed. So far, Mamo is less a character than the precondition of the whole story, but exactly why her spirit is still unsettled remains a mystery, as does the nature of Orla's seemingly ambivalent relationship to her grandmother. As Orla and Jo circle round the village, marking a map to chart their progress, the two women develop a wary yet increasingly warm friendship (and perhaps something more?), and each reveals secrets. Two things really impress me about Mamo. One is the sense of atmosphere conveyed by Milledge's gorgeously colored pages (produced in collaboration with color flatter Belle Murdoch). The environments here remind me of Kazuo Oga's beautiful art direction and backgrounds for various Studio Ghibli films, including many of Miyazaki's: My Neighbor Totoro, Kiki, and so on. The mingled colors and shadows, the play of shadow over color and over forms, results in a transporting loveliness. Even the darkest moments are dappled with filtered sunlight, a delicious effect that Milledge can't seem to get enough of. I'm reminded of Tillie Walden's bold way with colors, as well as, of course, the quietly lovely countryside of Totoro. The other thing that gets me is, again, Milledge's understanding of magic. Mamo has its own theory or philosophy of magic, which emphasizes giving, accepting, and mutuality: the sharing of power (power shared is power doubled). Magic means relationships, and that means constraints and obligations, not just unbridled power. Favors and connections are everything. The idea that magic comes with obligations and limits isn't new (I picked something like this up from reading Le Guin's Earthsea, long ago). But Milledge seems to have thought this issue over very carefully. Logically, her philosophy of magic provides the ideal setting for the story of a budding relationship; really, the relationship and the magic are the same thing. I get the feeling that magic, in Mamo, is a meaningful system built out of mutual regard and strong feeling. All this is conveyed without pedantry or tedious exposition. Many fantasy writers have tried to work out a system of magic that preserves a sense of mystery and wonder without giving way to an anything-goes sort of sloppiness. Milledge does this better than most, the result being a very grounded, though no less wondrous, type of fantasy. Mamo is the kind of comic book that overcomes my habit of trade-waiting: a floppy series that compels me to break down and just buy the next issue, already! A warmly humanistic, implicitly queer-positive, inclusive fantasy, it's also an aesthetic delight. I recommend checking it out.

0 Comments

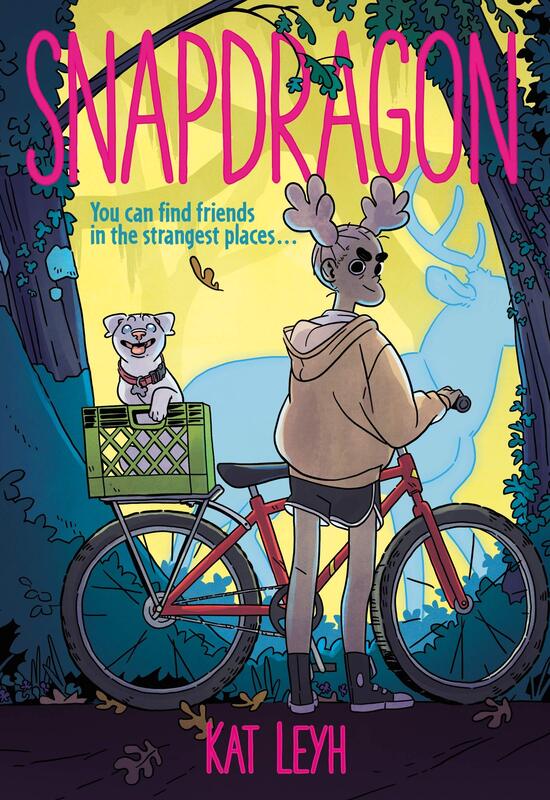

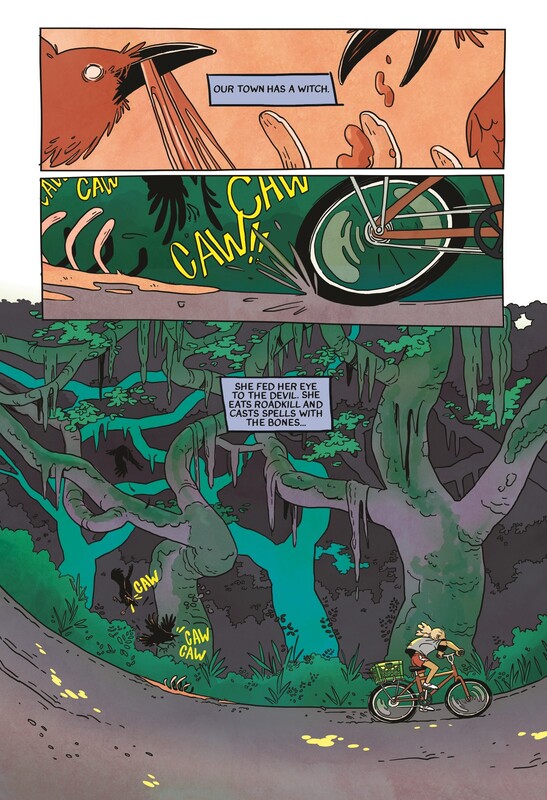

Snapdragon. By Kat Leyh. First Second, 2020. ISBN 978-1250171115, $US12.99. 240 pages. I favored Snapdragon to win this year’s Eisner Award for Best Publication for Kids (though, um, another book ended up winning). Of all the recent comics about witches that I’ve reviewed here, Snapdragon strikes me as the most sure-handed and persuasive, as well as the richest. It shares with most of the other “witch” books a progressive, inclusive, queer-positive ethos and Bildungsroman structure. Snapdragon, though, brings even more to the table, without ever overcramming or pushing too hard. Unsurprisingly, the book has a utopian, welcoming, vibe, but author Kat Leyh stirs in so much complicated humanness that the results never seem pollyannish or schematic. What we get is a winningly complex cast of characters, queer and trans representation that is central to the story while being gloriously unflustered and direct, spooky supernatural details that resolve into unexpected affirmations, and, above all, vivid and confident cartooning – one terrific, nuanced page after another. I was just a few pages in when I realized that I was in the hands of a master comics artist. The book has guts. Its first panel delivers a closeup of hungry birds tearing into carrion (roadkill), then zooms out to Snapdragon, or Snap, barreling through the woods on her bike. “Our town has a witch,” Snap’s opening captions tell us. “She fed her eye to the devil. She eats roadkill. And casts spells with the bones…” So, by way of opening, Leyh leans into the creep factor: But Snap, a fierce young girl, isn’t having it; the town’s rumors of a witch are “bull,” she thinks. “Witches ain’t real,” her skeptical thoughts go, as she brings her bike skidding to a halt in front of the witch’s (?) home. But soon enough Snap has joined forces with this supposed witch, a quirky old woman named Jacks who cares for animals but also salvages and sells the bones of roadkill to collectors and museums. Is Jacks a witch? Does she wield real magic? The book remains coy about this until halfway through, but Snap quickly bonds with Jacks, who welcomes Snap into her work, mentors her in animal anatomy and care, and becomes a sort of avuncular (materteral?) queer role model. That bond helps Snap claim her own implied queerness – that, and Snap’s friendship with Lou/Lulu, an implicitly trans schoolmate labeled as a boy but anxious to claim her girlness. All the book’s relationships are worked out with care, including the crucial one between Snap and her overworked but wise single mom, Vi. Leyh’s characterization is slyly intersectional, including sensitivity to class (Lu and Snap are neighbors in a mobile home park, a detail conveyed with knowing matter-of-factness). Almost every character has more to give than at first appears – the sole exception being Vi’s toxic ex-boyfriend, a heavy whose sudden reappearance at the climax is the book’s one surrender to convenience. Everything else feels truly earned. Snapdragon is the kind of book that, described in the abstract, might seem to be playing with loaded dice. In less sure hands, its story could have come across as pat and programmatic, a matter of good intentions as opposed to gutsy storytelling. But, oh, Leyh is absolutely on point here; her mix of irrepressible cartooning and narrative subtlety, of bounce and insinuation, is a wonder to behold. Snap and Jacks are great characters, and in good company. Their world feels real and vital. Leyh infuses their story with grace, understanding, and nonstop energy. I’ve read this book multiple times and expect to read it again. I’d read sequels, if Leyh wanted to offer any. And I’ll follow her whatever she does.

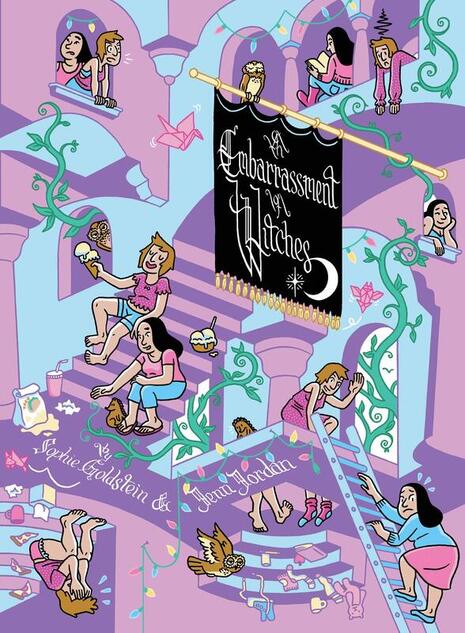

An Embarrassment of Witches. Written by Jenn Jordan and Sophie Goldstein; art by Sophie Goldstein. Coloring assistance by Mike Freiheit; calligraphy by Carl Antonowicz. Top Shelf, 2020. ISBN 978-0593119273, $US19.99. 200 pages. Lately I've been reviewing Bildungsromane about young witches in training (here, here, and here). I thought An Embarrassment of Witches would be one of those, but it really isn't. Yes, it's a coming-of-age story, but it's also a grad school comedy about the experiences of two fairly new adults (not young adults in the adolescent sense) whose loved ones are high-powered academics or wannabes living in a rarified intellectual world ripe for satire. It happens that this world is one in which magic is commonplace, one where you can go to grad school to study "metamystics," and where shopping malls include businesses like Taco Spell and Aleistercrowley & Witch. But the story does not focus on learning witchery or spellcraft. It deals with applying for jobs and school, with internships, and with tense people having relationships at a bemusing transitional moment in their lives. It reads like a Friends-style sitcom combined with an academic novel, but is not as acrid as that might sound. Tonally, it reminds me of John Allison's splendid college comedy, Giant Days; its character writing is just as adult and just as piquant, and it conveys a similar sense of benign absurdity. Briefly, the story focuses on two best friends and roomies, Rory (Aurora) and Angela, and how their friendship is sorely tested by the moves they have to make toward autonomous adulthood: feckless Rory walks away from her supercilious boyfriend and begins looking for a new direction in life, while Angela takes an internship supervised by, of all people, Rory's mother, a famed and fearsome academic. Lies, evasions, and secrets result in a complicated tangle. Eventually, Angela and Rory have to renegotiate the terms of their friendship on a more adult basis. The plot reveals the unreliability and stumbling humanity of just about everybody, without demonizing anybody (characters who at first appear flat turn out to have depths). The book is smart, funny, and endlessly inventive, and scatters little comic jewels on almost every page. Rory and Angela are knowingly and subtly written, with great attention to their brittleness and quirks and, especially, the mostly unspoken complexities of their relationship. This is witty, human, open-hearted stuff. Art-wise, An Embarrassment of Witches is a formally inventive knockout. The character designs are sharp and distinctive, the visual worldbuilding is a hoot, and the book looks like no other. Goldstein dispenses with gutters and borders, favoring jampacked full-bleed pages in which the panels rub right up against each other. The results are a bit overwhelming due to sheer density, but that jibes with the book's emphasis on complex social dynamics. It also makes the book a delight to page through again and again (the disorienting, Escher-like cover is just a hint of the pleasures and challenges inside). The limited color palette — two purples, a near-turquoise green, celeste blue, and a kind of mellow yellow — may sound iffy in the abstract, but works brilliantly in practice, making the book into a cohesive world of its own. All this is to say that the wittiness of the story is matched by an outpouring of visual wit. In short, An Embarrassment of Witches is a full-on delight.

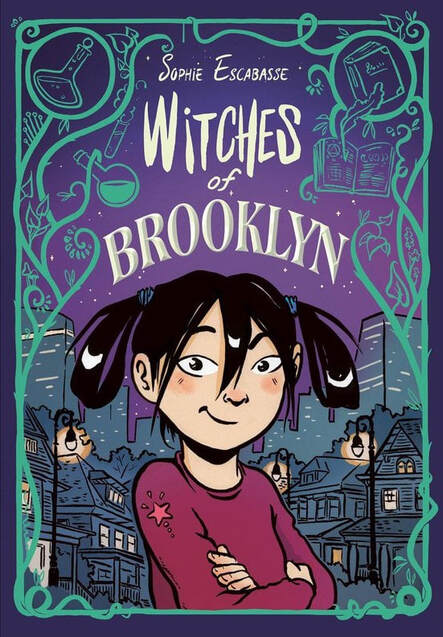

Witches of Brooklyn. By Sophie Escabasse. RH Graphic/Random House, 2020. ISBN 978-0593119273, $US12.99. 240 pages. In this middle-grade urban fantasy, the first in a planned trilogy, orphaned tween Effie is adopted by her eccentric aunts Selimene and Carlota, herbalists and acupuncturists who live in a quaint Victorian house in Flatbush. As it turns out, her aunts are also “miracle makers,” witches whose powers can bend reality and time—and Effie discovers that those powers run in the family. When a vaguely Taylor Swift-like pop star idolized by Effie runs afoul of some ancient magic and needs a cure, Selimene and Carlota take Effie into their confidence, and her training in magic begins. A clever, if rigged, story ensues, jammed with business, as Effie bonds with her aunts, makes friends at school, discovers the hazards of having power without knowledge, and becomes disillusioned with her former idol—but also saves her. The story abounds in Harry Potterisms and other well-worn tropes, and the frantic plot works against the bids for soulful characterization: for example, Effie begins as an embittered foster child with a chip on her shoulder, but then abruptly embraces living with her aunts, leaving all resentments and uncertainties aside. Hints of past unhappiness and family intrigue involving her late mother remain vague, perhaps foreshadowing sequels. There are plenty of loose ends. Author Sophie Escabasse’s style seesaws between joyous energy and fussy detailing. Her layouts are restless and dynamic, the traditional grids often enlivened by inset panels, frame breaks, and diagonals. There’s an enjoyable, exploratory quality about all this—the delight of seeing what a page can do—though the cluttered detail and overbusy coloring bog things down a bit. (On some pages, backgrounds are grayed out to bring the characters forward, which I think helps.) The characters are all distinct, with different silhouettes, head shapes, and faces—so different that they almost seem to have been drawn by different artists. Effie’s aunts are the most vividly realized and charming; in particular, Selimene, mercurial and feisty, stands out from the general busyness, with a comical design that recall Escabasse’s avowed influence André Franquin. Overall, Witches of Brooklyn strikes me as pretty good but also very familiar—so, I’m lukewarm toward it, despite its many good, smart moments. The sequels, I hope, will aim for less obvious plot-rigging, more rooted and consistent characterization, a sharper sense of what magic means and can do in this story-world, and, visually, not so much over-egging of the settings and details. As is, this first book crams in about three books’ worth of material and potential—I’d like to see Escabasse explore her world at a more deliberate pace. The second book reportedly will drop at the end of August.

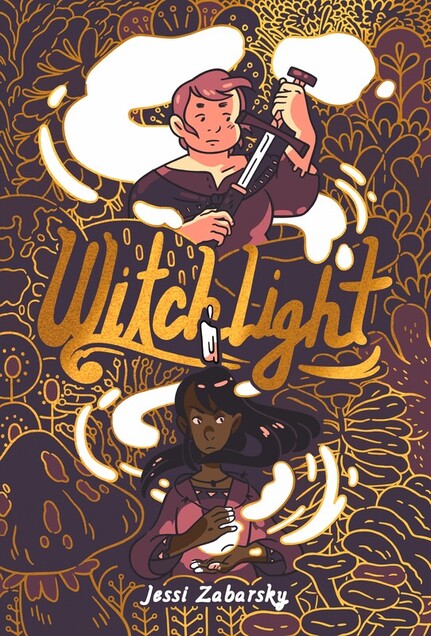

Witchlight. By Jessi Zabarsky. With coloring by Geov Chouteau. RH Graphic/Random House, 2020. ISBN 978-0593119990, $US16.99. 208 pages. I guess you say that this review is part of an occasional series (heh). In an unnamed land—a marvelous, culturally syncretic fantasy world—two young women undertake a magical quest and, as they go, learn how to care for one another. One of them, Lelek, volatile and enigmatic, is a witch who has lost half her soul. The other, her newfound friend (well, at first her kidnappee) Sanja, is determined to help find it. Love blooms between them—a matter of blushing shyness at first, but then owned and enjoyed with a winning matter-of-factness. As they travel, Lelek and Sanja scare up money by challenging local witches to duels, but often end up learning from those same witches; their travels uncover woman-centered communities and hints of matriarchal lore and magic. The larger culture hints at witch-hunting and misogyny, and this leads to a harrowing twist in the final act, but also, by roundabout means, to the resolution of a mystery and a ringing affirmation of Lelek, Sanja, and everyone they’ve befriended en route. Originally published by Kevin Czap’s micro-press Czap Books in 2016, Jessi Zabarsky’s Witchlight is a gorgeous and soulful feast of cartooning in a clear-line but vigorous, rounded style (which reminds me a bit of Czap’s own). It grows more confident in its linework and layouts as it goes. Beautifully colored by Geov Chouteau, the pages sing with an assured minimalism and harmony. I suppose the backstory and conflicts could be established more firmly—the plot might be clearer—but on the other hand, I enjoyed immediately diving back into the book to better understand its dreamlike premises. The book’s feminist, antiracist, and queer-positive ethos are a part of that dream and arise organically from the world Zabarsky has created; she uses her secondary world to imagine a better one. The utopian vibe is complicated by emotional and social nuances and an earned sense of loss and struggle. More than anything, Witchlight radiates a sense of love, offhand intimacy, and the thrills of self-discovery. Zabarsky clearly delights in her characters. She is a great cartoonist, with another graphic novel promised from RH Graphic by year’s end. I can't wait!

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed