|

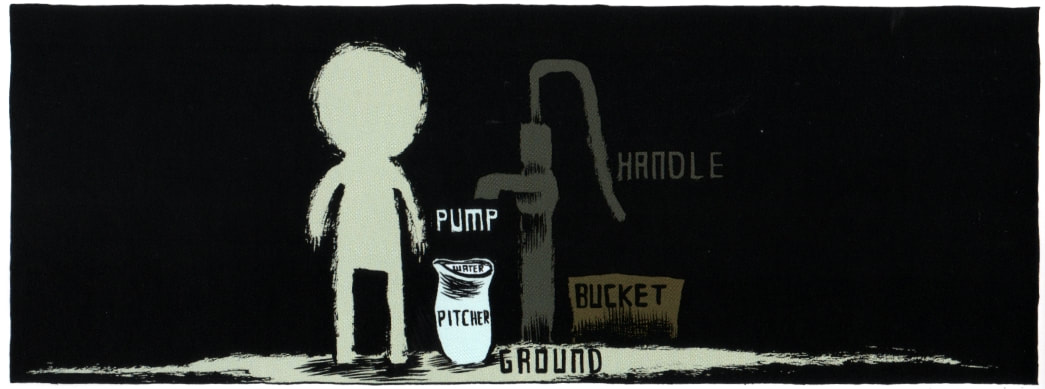

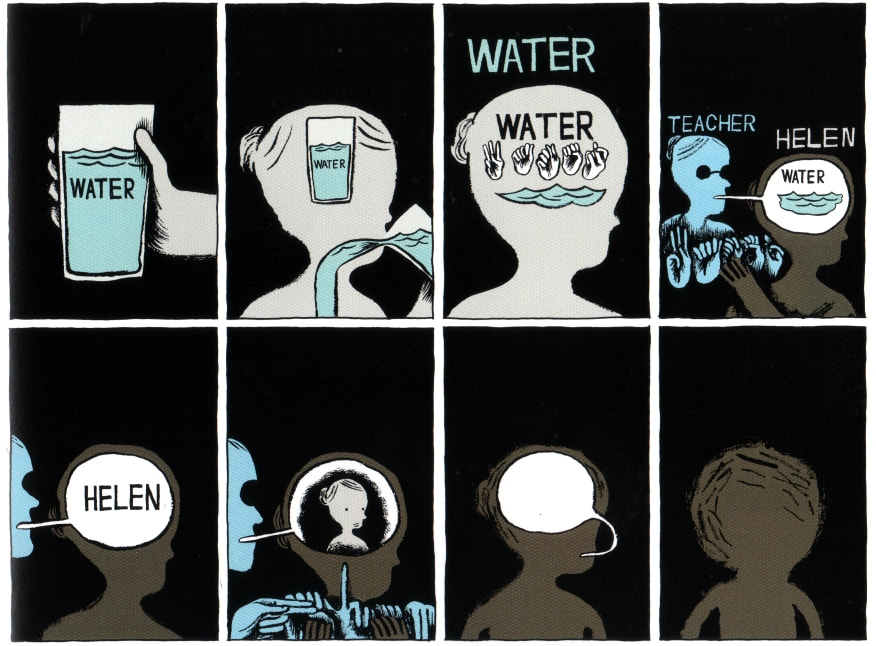

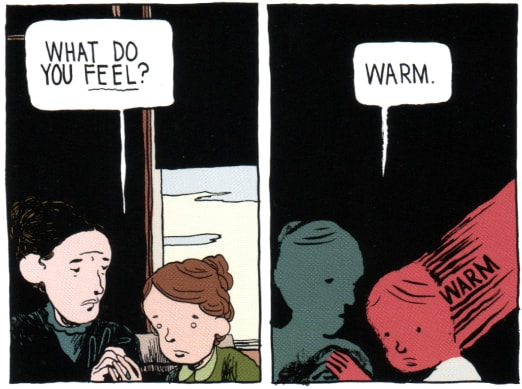

Annie Sullivan and the Trials of Helen Keller. By Joseph Lambert. Edited by Jason Lutes. Disney/ Hyperion, 2012. ISBN 978-1423113362. $17.99, 96 pages. Winner of the Will Eisner Award for Best Reality-Based Work, 2013. I have a dozen copies of Joseph Lambert's Annie Sullivan and the Trials of Helen Keller in my office. It's that good. I bought most of those copies through Alibris just over a year ago while preparing to teach my grad seminar "Disability in Comics." I had always intended Annie Sullivan to be a required book in that class, along with such other comics as Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary, The Spiral Cage, Epileptic, El Deafo, and Hawkeye: Rio Bravo. In fact Annie, along with José Alaniz's Death, Disability, and the Superhero, was one of the books that inspired me to teach the class in the first place. When I discovered that Annie was out of print, I lost my mind a bit, but then decided to scrounge up multiple used copies on my own dime and turn my office into a lending library. So, I ended up with a lot of Annie, and loaned out copies for several weeks. It's criminal that this modern classic is out of print – and I hope someone does something to change that soon. Annie Sullivan is part of a series of comics biographies packaged by the Center for Cartoon Studies for publisher Disney/Hyperion (2007-2012). These include books on Harry Houdini, Satchel Paige, Amelia Earhart, and Henry David Thoreau. All the books are hardcovers that run about 100 pages, and all are good; John Porcellino's Thoreau at Walden is wonderful. But Lambert's book, I believe, is one for the ages. Why do I admire this book so much? Lambert, whose work I came to know through The Best American Comics 2008 (edited by Lynda Barry) and then his story collection I Will Bite You! (2011), is simply a great cartoonist. His work displays a patience for careful breakdowns and repetition which approaches that of Harvey Kurtzman or of a top-notch humor strip artist. His drawing is simplified in appearance but also nuanced and emotionally precise, capable of capturing crucial subtleties of gesture and expression. Further, he has an appetite for expressing feeling and sensation through variations in traditional form; he can make a regular, unvarying grid seem musical and powerful. Feeling and sensation are the life's blood of Annie Sullivan, a book that works cannily, in an austere, rhythmically controlled way, to convey how its title characters experience the world in spite of (or through the filter of) isolating sensory impairments. Lambert does this with a poet's command of meter and a true biographer's interpretive sensitivity. One of the things Annie Sullivan does so well is inevitably, perhaps cruelly, ironic: it finds ways to visually convey non-visual experience, particularly haptic experience: the experience of handling things, of placing your hand in someone else's, of spelling things out with your fingers, and so on. Annie Sullivan taught Helen Keller, who lost her sight and hearing before she turned two, to recognize things in the world with her hands, and to communicate through finger spelling. Keller wrote in her autobiography, The Story of My Life (1903), that her tutor Sullivan revealed to her "the mystery of language," a gift that, she said, "awakened my soul, gave it light, hope, joy, set it free!" Lambert does a stunningly smart job of communicating both how Sullivan taught Keller and how hard it was. His pages convey Helen's haptic world and her opening-out into written language, using a range of techniques: tight, inescapable grids; nearly all-black panels and stark contrasts of light and darkness; isolated and stylized figures; systematic color-coding of figures and objects; inventive rendering and placement of single words; and stylized iconic hands to represent finger spelling. Formally ingenious, these techniques are also moving, for they show the extent of Helen's isolation, the intense, mutually dependent relationship between Helen and Annie, and the cascading emotional consequences of Helen's growing literacy. In a profound sense, Lambert's book is about obstacles to communication, and how, in the singular Hellen/Annie relationship, these were overleapt. Again, to render haptic experience visually is unavoidably ironic. In my class we discussed not only the formalistic means but also the ethics of this approach, in comparison and contrast to other comics' visual depictions of non-visual experience (particularly Marvel's Daredevil). Annie Sullivan and the Trials of Helen Keller cannot perfectly convey Helen's phenomenal world. It cannot help but be an ocularcentric evocation of sightless experience. That's a problem. Yet the book is a highwater mark in the synesthetic use of comics' visual form to suggest life beyond the visual; in this, it strikes me as both ingenious and sensitive. Another thing that makes Annie Sullivan so strong is its dual focus on teacher and student. Sullivan comes off, not as some beneficent "miracle worker," but as a conflicted, heroically stubborn, frank, fierce, and deeply sorrowful person, shaped by her own visual impairment, her wretched years spent living in an almshouse, the tragic loss of her brother, and her just resentment of gender convention and the straitened roles available to women in 19th century America. Sullivan appears to have been a difficult and marvelous person, sometimes bitterly acerbic, and moved by abiding grief and anger. At times Lambert depicts her teaching of Helen as autocratic, harsh, even borderline abusive. Yet he also shows how and why it worked. Lambert, that is, portrays Annie with great empathy but also unsentimental candor. The book is tough-minded, sketching in the horrors of Annie's early life discreetly but powerfully and showing her resistance to the men and women who sought to control her. What's more, in its depiction of teacher and student together, Annie Sullivan avoids the triumphal cliches of children's biography. While Lambert rightly depicts Sullivan's breakthrough with her pupil as remarkable (the famous scene at the water pump, recounted in Keller's biography and in the many versions of The Miracle Worker), that is not the end of the story, and the book's second half delves into other "trials." Chief among these is an accusation of plagiarism that hurt Keller deeply, bedeviled her early efforts as a writer, and estranged Keller and Sullivan from their benefactors in the field of education for the visually impaired. In the end, what emerges is not a simple story of Helen's triumph over adversity but a complex sense of Helen and Annie's profound dependence on one another. In fact, the conclusion of the book is oddly melancholy, offering none of the facile reassurances that ableist stories of overcoming disability tend to offer. In sum, Annie Sullivan is a brilliant feat of writing as well as cartooning and design. It really is a shame that Annie Sullivan and the Trials of Helen Keller is out of print. I can't say that enough.  UPDATE: It's back in print! As of October 2018. Yes!

0 Comments

The nominees for the 2018 Will Eisner Comic Industry Awards were announced today, and they make for a fascinating ballot!  The Eisners are the leading awards in the comic book and graphic novel industry. Established thirty years ago and given out each summer at San Diego's Comic-Con International, they've been organized by CCI's Jackie Estrada since 1991. The awards are voted on by industry professionals (this year's voting deadline is June 15). This year's winners will be announced in an awards ceremony at CCI on Friday, July 20. This year's nominees were selected, as usual, by a judging panel representing various sectors and stakeholders in the comics business. The panel included Young Adult librarian and former YALSA President Candice Mack, journalist and podcaster Graeme McMillan, comics and pop culture retailer Tate Ottati, writer and comic book creator Alex Simmons, longtime Comic-Con and Cartoon/Fantasy Organization organizer William F. Wilson, and my esteemed colleague, scholar-teacher Nhora Lucía Serrano (with whom I've worked in the Comics Studies Society). To me, the news of the Eisner nominations tends to be more exciting than the award results, because the ballot is such a cross-section of comics culture and always contains surprises. Every Eisner ballot documents a complex process of negotiation and compromise. I know how complex it can be, because in 2013 I served as a judge (along with Michael Cavna, Adam Healy, Katie Monnin, Frank Santoro, and John Smith). It's an experience I will not forget. Judging the Eisners entails reading many, many comics in a short time, then coming together with colleagues--smart, dedicated folks with diverse perspectives and interests--and working across differences to fashion a ballot that gathers up the various strands of long-form comics and represents a fair sample of outstanding work. The judges' final summit (typically a long weekend in April), at least as I experienced it, is about hours and hours of last-minute reading, and then, just as importantly, hours and hours spent around a table hashing out the ballot. Intense, exhausting, and delightful. I remember reading late into the night; I remember chatting and arguing; I remember a room that smelled like paper. Hats off for this year's judges--librarian, journalist, retailer, creator, organizer, and scholar--for their hard work, and for crafting a ballot that reflects exciting changes in the comics field. Of particular interest to KinderComics are the young readers' categories: BEST PUBLICATION FOR EARLY READERS (UP TO AGE 8):

BEST PUBLICATION FOR KIDS (AGES 9–12):

BEST PUBLICATION FOR TEENS (AGES 13-17):

These categories have become quite competitive, reflecting the surge in young readers' comics and the influence of children's and YA librarians, who have generally championed the graphic novel format. Notably, these are categories in which the final Eisner voting does not predictably follow popularity in the direct market (i.e. comic shops) but instead seems to reflect the interests of other communities. There have been strong winners in these categories over the past few years, and this year's nominees are a strong, exciting, varied group. Again, kudos to the judges for selecting such a wide-ranging, unconventional set! Beyond the above categories, there are children's and YA comics-related nominees in others, such as Best Academic/Scholarly Work (Picturing Childhood: Youth in Transnational Comics, edited by Heimermann and Tullis); Best Comics-Related Book (How to Read Nancy: The Elements of Comics in Three Easy Panels, by Karasik and Newgarden); Best Digital Comic (Quince, by Kadlecik, Steinkellner, and Steinkellner); and Best Short Story (“Forgotten Princess,” by Johnson and Sandoval, Adventure Time Comics #13). Also, some of the above creators are nominated in individual categories: Lorena Alvarez for Best Writer/Artist, Isabelle Arsenault for Best Penciller/Inker, Ramón K. Perez for Best Penciller/Inker, and Federico Bertolucci for Best Painter/Multimedia Artist. In fact, this year may mark a new high point in individual nominations for creators of young readers' comics. The ballot gives me an exciting sense of children's and YA comics as emphatically mainstream and recognized for their artistry and daring as well as their accessibility. It's such a strong ballot overall, with many startling inclusions. Beyond children's and YA comics, check out "A Life in Comics: The Graphic Adventures of Karen Green" (Best Short Story), or Pope Hats #5 (Best Single Issue), or the startling range of the whole Best Anthology category. Check out (wow) Small Favors in Best Graphic Album--Reprint, or Kindred in Best Adaptation from Another Medium. Or My Brother’s Husband in Best U.S. Edition of International Material—Asia. Among reprints, check out the two gorgeous Sunday Press books (Best Archival Collection/Project—Strips) and Conundrum's Collected Neil the Horse (Best Archival Collection/Project—Comic Books). There are many gutsy choices in this year's list—congratulations, judges, and happy reading, everybody!

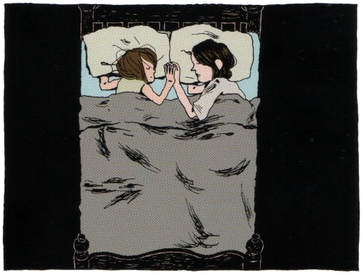

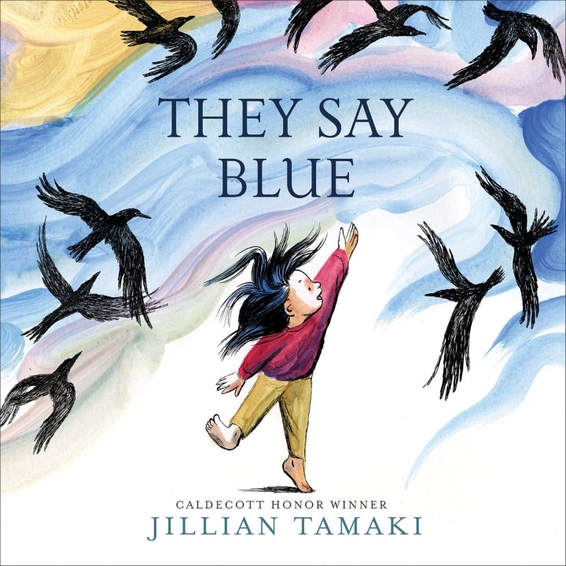

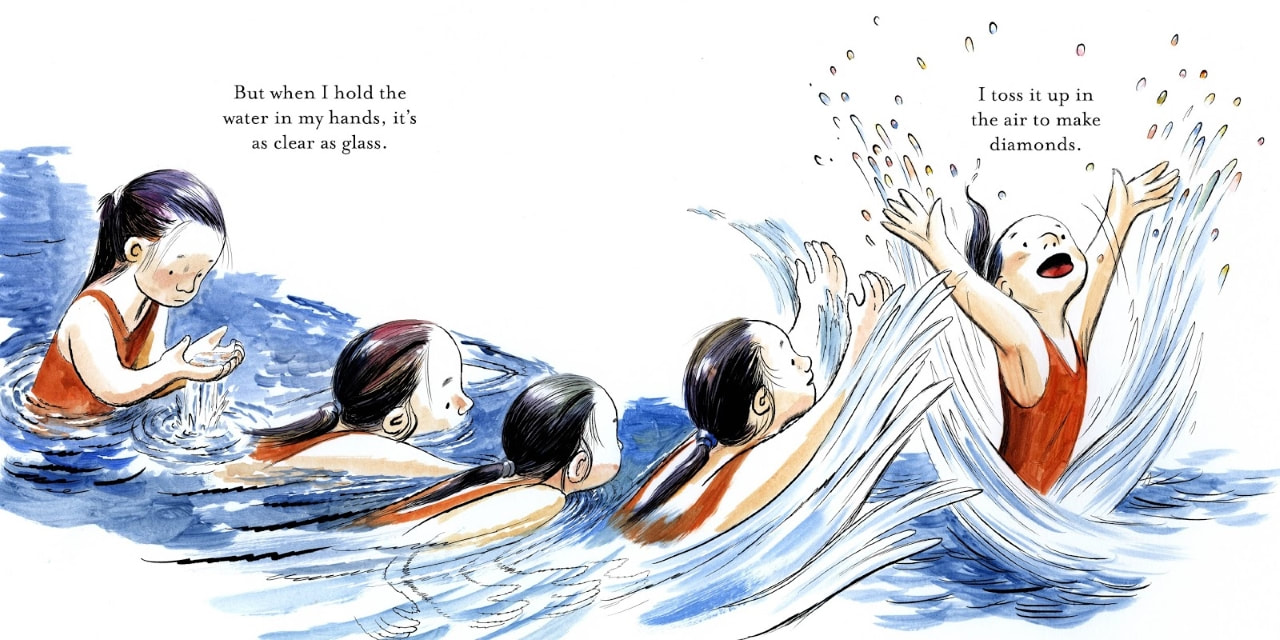

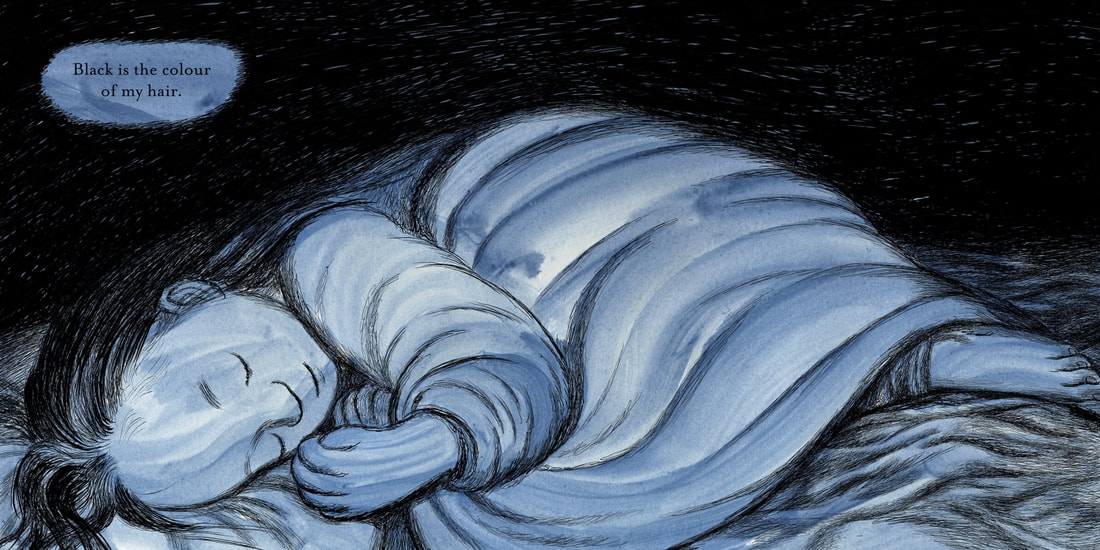

They Say Blue. By Jillian Tamaki. Abrams Books for Young Readers, March 2018. ISBN 978-1419728518. $17.99, 40 pages. Jillian Tamaki (Skim, This One Summer, SuperMutant Magic Academy, Boundless, much more) has just done her first children's picture book, They Say Blue. It's a dream: a lyrical, drifting book about seeing and not seeing, about a world of colors, about raw perception but also how we reflect upon and try to make sense of our perceptions. Painted in flowing acrylics on watercolor paper, with overlays of inked drawing via Photoshop, They Say Blue consists almost entirely of full-bleed double-spreads dotted with short, vigorous bursts of text. Lavishly illustrated yet sparsely written (roughly twoscore sentences run through its twoscore pages), it is less a storybook than a visual poem, liquid, freely expressive, and unpredictable. It focuses on the aesthetic sense and restless intelligence of a young girl with an artist's eye, for whom ordinary things can be extraordinary. The young narrator treats common sights and happenings as festivals of color, light (or darkness), and warmth, even as she sees the world around her in a here-and-now, everyday sort of way. She comes across not as some idealized Wordsworthian poet-child (though the book does partake of that spirit, a bit) but as a believably curious and engaged girl. Wonder and watch are key words, and wonder well describes my own response to the book. In other words, They Say Blue is a credible and lovely evocation of a child's creative eye and voice. It recalls, for me, the pithy matter-of-factness of Krauss and Sendak's A Hole Is to Dig, or the free-associative riffing of Crockett Johnson's Harold. It's more visually extravagant than either of those, though, recalling how the modernist here-and-now picture books of the early 20th century, the kind championed by Lucy Sprague Mitchell and Margaret Wise Brown, captured children's daily lives and intimate concerns with simplified, streamlined prose-poetry yet also, often, with rapturous, brilliant images. Tamaki is working that same ground, in (as she has said) a quite traditional way. It's a tradition less about story than about a child's looking and thinking, that is, about being in the world. I think of Brown's books with Leonard Weisgard (such as The Noisy Book, The Little Island, and The Important Book) or of course her work with Clement Hurd (most famously Goodnight Moon) -- books about ordinary sensations or the reassuring rhythms of life. They Say Blue, you can tell by its very title, is about the young girl stacking up what "they" say against what her own experience tells her. It begins with a nonfigurative spread of pure blue -- a field of overlapping brushstrokes -- and the simple observation, They say blue is the color of the sky. But, as we turn the page, then the narrator measures what "they say" against her own vision, in this glorious spread: Turning again to the next spread, we see the girl swimming through, gazing at, and splashing in seawater: five drawings of her combined into a single image. In picture book critics' parlance, this is a clear case of simultaneous succession or continuous narrative -- but to me the important thing is that it shows the girl's immersion in experience, and her way of questioning what she is told, but then also reveling in what the world gives: But just as important as these rhapsodic passages are subtle ones that chip away at the idealization of childhood. My favorite is a series of two openings that together raise up but then undercut an idyllic fantasy. The first shows our narrator sailing in an imaginary boat over a field of grass "like a golden ocean" (more simultaneous succession: delightful movement). The next, though, shows a fairly bleak, rain-sogged landscape and the girl trudging homeward through foul weather, dragging her backpack behind her against a sky of grim clouds and dull grass. She concedes, It's just plain old yellow grass anyway. I can almost hear the weariness in her voice. Thankfully, it doesn't last, but I love the way Tamaki works these bum notes into the book. Make no mistake: They Say Blue is gentle. It is affirming. But I like the way it registers moments of doubt, bewilderment, and everyday muddling. Its poetry is an everyday sort of poetry, as in, Black is the color of my hair. / My mother parts it every morning, like opening a window. Opening a window on new ways of seeing familiar things is exactly what the book does. Many comics artists struggle when moving into picture books, but They Say Blue engages picture book form and tradition knowingly. Tamaki's recent interview with Roger Sutton at The Horn Book shows how well she knows the form, and artistically she takes to the picture book as if it were an answer to a question she has been asking. In a conversation with Eleanor Davis at The Comics Journal last summer, Tamaki admitted that "I can feel increasingly confined by the image part of comics," and reflected that, at least "for more commercial works, the images [in comics] need to be a lot more literal." She described herself as trying to "stretch that word-image relationship." More recently, in an interview with Matia Burnett at Publishers Weekly, Tamaki contrasted the experience of making comics with the experience of making picture books: They’re pretty different. The poetry and distillation of kids’ books, in word and image, is a completely different challenge. A lot of comics [work] is just grinding out pages, if the images communicate what’s happening, that’s usually good enough in a pinch. A picture book’s images have to evoke, which is much more ephemeral. My sense is that They Say Blue exercises a different part of Tamaki's artistry, while still being very clearly a Jillian Tamaki book. I'm glad. The book is beautiful, a work of deft visual poetry. It confirms that, as Eleanor Davis put it, "there is no one who is better."

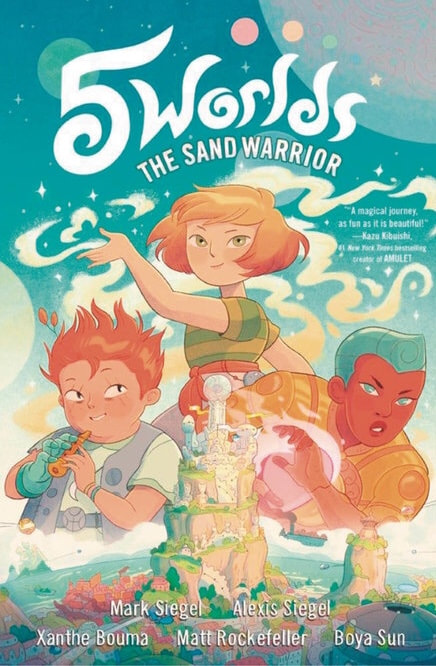

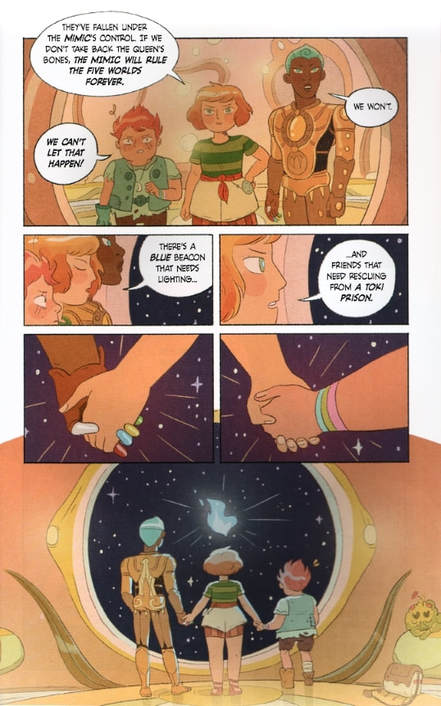

5 Worlds: The Sand Warrior. By Mark Siegel, Alexis Siegel, Xanthe Bouma, Matt Rockefeller, and Boya Sun. Random House, 2017. ISBN 978-1101935880. 256 pages, $16.99. A Junior Library Guild Selection. The Sand Warrior, a busy, fast-paced science fantasy adventure set in a wholly invented universe, teems with lovely ideas and designs. It is the first of a promised five-book series in the 5 Worlds (one book per world), and sets up a patchwork of different cultures, ecologies, technologies, and species. Indeed the book does some terrific world-building, the result of a complex collaborative process involving co-scriptwriters Mark Siegel and Alexis Siegel (brothers) and designer-illustrators Xanthe Bouma, Matt Rockefeller, and Boya Sun, working from an initial premise and designs by Mark Siegel. (Interestingly, Mark Siegel is founder and editorial director of First Second Books, but this is not a First Second title.) Reportedly, Mark Siegel conceived 5 Worlds as a project he would draw on his own (fans of Sailor Twain, To Dance, and his other books know that he could pull it off). However, as he and brother Alexis brainstormed the story, its plot and worlds grew so grand that he decided to turn it into a collaborative venture. Recruiting three recent graduates of the Maryland Institute College of Art — Bouma, Rockefeller, and Sun, who all met in a Character Design class at MICA — Siegel set in motion a complex, geographically dispersed teamwork, reportedly enabled by Google Drive, Skype or Zoom calls, texting, and secret Pinterest boards (see below for video links that shed light on this teamwork). The resulting book is remarkably consistent and aesthetically whole for such an elaborate process. It appears that Bouma, Rockefeller, and Sun became much more than hired illustrators on the project. They helped design and flesh out the worlds, and divided the page layouts and drawing (based on Mark Siegel’s thumbnails) in a selfless and seamless way. At the CALA festival last December, I bought a making-of zine (5W1 behind-the-scenes) from Bouma and Rockefeller, full of sketches and studies — a bit of archaeology for process geeks like me — and it intrigues me almost as much as the finished book. Visually, what has come out of that collaborative process is lovely. Story-wise, though, The Sand Warrior suffers from the greater ambitions of 5 Worlds. Its hectic, ricocheting plot zips forward too quickly for me to get a grip, even as it lurches into backstory with sudden, unexpected moments of info-dumping. Insertions here and there try to help the reader make sense of the 5 Worlds mythos (and do pay attention to the maps and legends on the endpapers). World-design and baiting-the-hook for future volumes get in the way of character development, even though the lead characters are soulful and troubled in promising ways. To be fair, there are moments of gravitas and emotional force amid the headlong action sequences, and there are consequential, irrevocable outcomes too. These impressed me. Yet I’d have liked to see longer spells of quietness, reflection, and clarity between the frenzied set pieces. The book actually does quietness rather well, but not enough; it has too much ground to cover. As a result, the plot comes off like a raw schematic of familiar things: prophecy, Chosen One, destiny, self-discovery, and reveals and reversals that I saw coming a long way off. When archetypal fantasy is stripped to its bones, too often the bones appear borrowed, and shopworn. It takes new textures to freshen those familiar elements. When the plot is streamlined to the point of frictionlessness (as in, for example, the breathless film adaptations of The Golden Compass and A Wrinkle in Time), we can all see that the game is rigged. My advice would be to slow down! Briefly, the plot of The Sand Warrior concerns the rival societies of five worlds: one great planet and her four satellites, each hosting a distinctly different culture. All five worlds are in crisis, dying of heat death and dehydration (a timely ecological allegory, ouch). According to an ancient prophecy, this catastrophe can be averted only by relighting the “Beacons” on each world, long since extinguished but still sources of wonder and controversy. Not everyone believes in this prophecy, and one world has plans of its own—prompted by the machinations of a dark, obscure adversary known only as the Mimic. Invasion and violence ensue. Our heroes, led by Oona, a mystically gifted yet diffident and halting “sand dancer,” seek to reignite the Beacon of their world and then defeat the Mimic. It’s all very complicated, with environmental and political workings and some of the plot machinery you'd expect to find in a fantasy epic with a prophesied hero. Bravely, The Sand Warrior tries to fill in all that detail on the fly; it foregoes the usual expository business of front-loading its mythos with a prologue, instead picking up backstory on the go. I appreciate that. However, this strategy poses challenges in terms of pacing and structure. Reading the book, I often felt as if I was being introduced to places and cultures just as they were being wrecked. The effect is like starting Harry Potter with the Battle of Hogwarts: too much too quickly, and with one or two familiar moves too many. By novel's end, even more interwoven secrets, and even more evidence of Oona's special nature, are hinted at—a touch too much—and the last pages almost desperately try to springboard into the coming second volume (out May 8). We close with obvious gestures toward self-realization and resolution but also toward open-endedness and further complication. Whew. Frankly, there’s too much to take in, and The Sand Warrior struggles to find a pace that is exciting but not skittish. Still, I look forward to further chapters in 5 Worlds. This five-headed collaborative beast, as frantic as its first outing may be, somehow has a single heart and speaks with a single voice. Sure, The Sand Warrior is overstuffed with known elements; the back matter acknowledges, among others, LeGuin, Bujold, and Moebius as inspirations, and many readers will also detect traces of Avatar: The Last Airbender and of Miyazaki (perhaps the beating heart of graphic fantasy nowadays). The story travels well-trod paths. But I like those paths; I like high fantasy. I also like the cultural complexity and diversity suggested by the book’s elaborate world-building. Further, the art attains a gorgeous fluency, with stunning color (reportedly Bouma did the key colors) and a lightness of touch, or delicacy of line, that recalls children’s bandes dessinées at their most ravishing. What’s more, the environments are transporting feats of design: giddy exercises in make-believe architecture and technology with a charming toy- or game-like density of detail. Naturally I want to stick around. I expect that The Sand Warrior will improve with rereading once more of 5 Worlds is revealed, and I look forward to seeing the characters through their troubles and gazing at whatever fresh landscapes they traverse along the way. In scope, and certainly in complexity of mythos, 5 Worlds compares well with Jeff Smith’s Bone — what it needs is patience, and pacing. Sources on the 5 Worlds Collaboration:

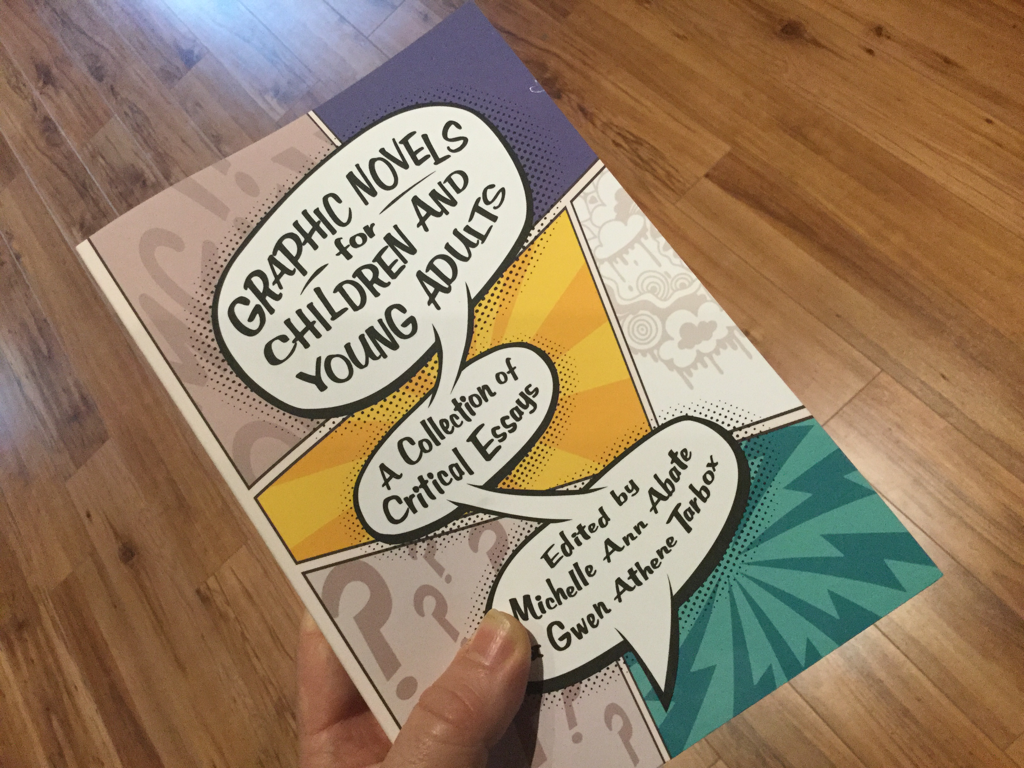

Graphic Novels for Children and Young Adults: A Collection of Critical Essays. Edited by Michelle Ann Abate and Gwen Athene Tarbox. University Press of Mississippi, 2017. ISBN 978-1496818447. Paperback, 372 pages, $30. Newsflash! Graphic Novels for Children and Young Adults (2017), edited by Michelle Ann Abate and Gwen Tarbox, and including a score of essays by diverse authors, has just been (re-) released in paperback. It came out last year, but now, at last, I have a softcover copy of my own that I can annotate and mark up in the usual ruthless way. Yes! This is an essential collection, a landmark in the academic consideration of children's and Young Adult comics. Readers of Gwen's contribution to our Teaching Roundtable may know, or may wish to know, that her post builds on and adds detail to ideas set forth in this book, specifically in her essay, "From Who-villle to Hereville: Integrating Graphic Novels into an Undergraduate Children's Literature Course." Also, Roundtable participant Joe Sutliff Sanders has an essay in the book on children's digital comics! I haven't quite figured out how to teach English 392 yet, but I do know that this is going to be one of the required texts.

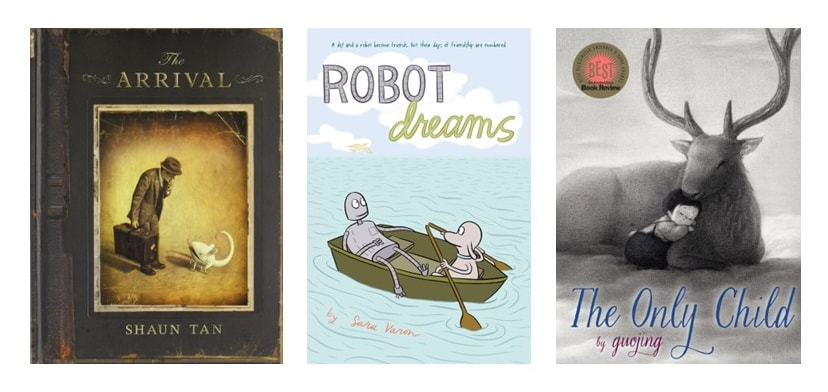

A guest post by Gwen Athene Tarbox The KinderComics Teaching Roundtable continues! Today my colleague Dr. Gwen Athene Tarbox, expert in comics and children's literature and co-editor of the essential Graphic Novels for Children and Young Adults (2017), responds to posts by me and Joe Sutliff Sanders regarding the challenges of teaching comics for and about children. This series arises from my preparations for teaching (this coming Fall) a seminar called Comics, Childhood, and Children’s Comics. Gwen, thank you for contributing your voice here! - Charles Hatfield When it comes to identifying strategies for teaching children’s comics, context matters. As Charles embarks upon the process of developing an elective honors seminar, ENGL 392, Comics, Childhood, and Children’s Comics, he knows that his students have at least some interest in comics and are probably used to researching and writing about interdisciplinary subject matter. The Department of English at California State University, Northridge frequently offers courses in popular culture, and Charles is one of a number of faculty members who integrate comics into their syllabi. Could there possibly be a downside to teaching childhood and children’s comics within a supportive academic environment? Well, not really, but as Charles tells us in his roundtable post, being faced with a seemingly unlimited set of topics and approaches at the nexus of two complex fields makes for a daunting task. Joe, a Lecturer in the Faculty of Education at the University of Cambridge, teaches in a system where students are exposed to a variety of instructors and subjects related to literature, education, and the history of education, as part of a three-year program that combines seminars with tutorials. As he explains in his roundtable post, “I have about two hours to give the students a fiery introduction to the material that will drive them to go educate themselves about the subject once I’m gone.” Many of Joe’s colleagues are interested in visual culture, as are the undergraduate and graduate students with whom he works, but the UK university system relies upon students being much more self-directed, so Joe may end up doing more of his teaching informally, in conferences with individual students. His concerns about teaching canonical texts, which are overwhelmingly male and White, should be shared by anyone who teaches in our fields, and Joe may have to rely upon handing out bibliographies and carving out an online or podcast resource for his students to ensure that they are familiar with a broad spectrum of comics texts. My own experience in the Department of English at Western Michigan University involves integrating comics into ENGL 3820, Literature for the Young Child, and ENGL 3830, Literature for the Intermediate Reader, courses that are required for elementary education majors, but can also serve as general education electives. Creative writing majors, inspired by the success of J.K. Rowling, Jacqueline Woodson, and Kwame Alexander, view 3820 and 3830 as venues for unlocking the secrets of character development or comparing how different media impact the way a narrative unfolds. However, regardless of their motivations for taking my courses, all but a few of my students tell me up front that they are AFRAID of comics—perhaps not as afraid as they are of taking Math 2650, Probability and Statistics for Elementary/Middle School Teachers… but for at least some of my students analyzing comics appears to be as terrifying as being asked to switch on their calculators. My context—preparing future teachers and aspiring authors—compels me to select texts that are frequently used in classrooms or are cutting-edge in terms of their form, and also means that many of my students are encountering comics for the very first time. Typically, I ease my children’s literature undergraduates into the study of comics by spending most of the semester focusing on visual rhetoric, first with picture books and illustrated novels and then moving on to hybrid texts such as Lorena Alvarez’ Nightlights and to films like Paddington or Coco. Then, on the first day of class devoted solely to comics, I hand out a few wordless offerings--Shaun Tan’s The Arrival, Sara Varon’s Robot Dreams, or Guojing’s The Only Child—and ask students to read them aloud. Reading aloud has become a major component of our children’s literature courses, so when students appear flustered and hesitate, it is not because they are unaccustomed to reading in front of their peers. Rather, they are hesitant because, and I give voice here to my students: “How do I know what to read first? What if I interpret something incorrectly? Do I take in the whole page first and summarize it? Or do I talk about each panel? Who is the narrator? Where is the narrator?” All of these questions lead us to a nuts-and-bolts discussion of form and content that occurs organically and is supplemented by excerpts from a variety of critical texts, including Joe’s essay, “Chaperoning Words: Meaning-Making in Comics and Picture Books” (Children’s Literature, 2013), Charles’s “Comic Art, Children's Literature, and the New Comic Studies” (The Lion and the Unicorn, 2006), and Paul Karasik and Mark Newgarden’s newly released How to Read Nancy. Since 2017, I have been working on a book, Children’s and Young Adult Comics, that will come out later this year from Bloomsbury Academic. Like Charles, I have struggled to carve out a narrow enough focus, and like Joe, I feel as if I have only a few short chapters to encourage readers’ investment in children’s comics. Writing an introductory guide to children’s comics has a lot in common with teaching children’s comics insofar as I spend as much time worrying about what I have left out as I do about what is actually on the page. Another venue that has contributed significantly to my understanding of how to share comics with my students is the Comics Alternative Young Readers podcast that I have been a part of since 2015. Working first with Andy Wolverton, and now with Paul Lai, I have had the chance to read dozens of children’s and YA comics every year and to talk about them with experts. Derek Royal, who co-founded and now runs The Comics Alternative, is another great resource whom I consult regularly and with whom I have interviewed a number of children’s comics creators, including Mairghread Scott, Tony Cliff, and Hope Larson. Finally, I was fortunate enough to co-edit Graphic Novels for Children and Young Adults: A Critical Collection (University of Mississippi Press, 2017—now available in paperback), with Michelle Ann Abate, and the process introduced me to over twenty scholars, from traditional literary critics to teacher educators to visual theorists and cultural studies experts, all of whom provide in-depth analyses of a host of contemporary children’s and YA comics. What heartens me the most, then, is that a large community is beginning to congregate around the study and teaching of children’s and YA comics. Charles and Joe, Laura Jiménez, David Low, Nathalie op de Beeck, Carol Tilley, Michelle Ann Abate, Philip Nel, and countless other amazing scholars are helping to create an ongoing dialogue about the intersection of two fields whose fortunes have often been linked, but have rarely been discussed together. And now we have KinderComics, Charles’s blog, as another important resource! (Note: this roundtable will continue in the weeks and months ahead. - CH) Gwen Athene Tarbox is a professor in the Department of English at Western Michigan University, where she teaches courses in children's and YA literature, as well as comics studies. She is the author of The Clubwomen's Daughters: Collectivist Impulses in Progressive-era Girls' Fiction (Routledge, 2001), co-editor with Michelle Ann Abate of Graphic Novels for Children and Young Adults: A Critical Collection (UP of Miss, 2017), and author of an upcoming monograph, Children's and Young Adult Comics, from Bloomsbury Academic. She has written articles on the comics of Hergé and Gene Luen Yang, on teaching comics, and on various topics related to children's literature. She is also co-host, with Paul Lai, of The Comics Alternative's Young Reader podcast, which airs towards the end of every month (www.comicsalternative.com).

A guest post by Joe Sutliff SandersMy colleague Dr. Joe Sutliff Sanders has kindly agreed to follow up my initial post in a series that I'm calling our Teaching Roundtable. This series stems from my preparations for teaching, in Fall 2018, a course called Comics, Childhood, and Children’s Comics, and my thoughts about the challenges of designing such a course. Thanks, Joe! - Charles Hatfield The best teaching that I have ever done has always been set up just beyond the edge of what I actually understand. You’ll hardly be surprised to learn, then, that I am in love with the idea of this blog. Charles does know a thing or two about comics, but he’s starting this blog conversation about the course not with what he knows, but with where he knows he’s going to have problems. It’s sick; it’s beautiful. I love it. As fate would have it, I happen to be in a very good situation to think about what can go wrong teaching childhood and comics. I’ve just relocated to Cambridge, where the teaching is very, very different from what I’ve done (and experienced) in every other classroom. The number one problem that I keep experiencing is that when the nature of the course wants us to lecture about the center, the books that Have To Be Known, then that nature is insistently nudging us away from the rich work done by people on the margins. For me, this urge toward the center is constant because at Cambridge we teach in a model that might best be understood as serial guest lecturing. Students have a different instructor almost every week, and once I have taught my subject, it might well never come up again for the rest of the term—indeed, the rest of the year. I have about two hours to give the students a fiery introduction to the material that will drive them to go educate themselves about the subject once I’m gone. If I can only ask them to read one book to prepare for my day in front of them, don’t I have to assign them the most canonical, traditional, familiar, central…let’s call it what it is: White…text possible? And Charles isn’t going to find the challenge much easier. Yes, he has the same students for a few months, so with some judicious selection, he can assign both the center and the margin. But there will be times when the nature of the subject seems to insist on safe, familiar choices. For example, while talking about the Comics Code, which was developed by influential White businessmen to protect their interests by playing to 1950s sensibilities of American middle-class propriety, how will he escape a reading list that is White, White, White? The men whose comics sparked the outrage were White; the public intellectual at the center of the debate was White; the men who wrote the Code were White; the books that thrived under the new regime were White. What reading material central to this history will be about anything but Whiteness? Or how about teaching the origins of cartooning? The most common version of the history of comics is populated by White Europeans who had access to the training and venues of publication necessary for a career as a public artist. I’m uncomfortable (to put it mildly) with a module featuring only them, but what are you going to do, not teach the center? These problems arise from comics as a subject matter, but there’s another problem rooted even more deeply in the specific aspect of contexts that Charles has chosen. The title of the course pinpoints "childhood," yes? Childhood’s close association with innocence, which is itself associated with Whiteness (if you don’t believe me, ask Robin Bernstein), is going to make straying from the center even more problematic. Here, as above, the enemy he faces is the nature of the subject. But there is another potential enemy. If—or, knowing Charles, when is the more appropriate word—he edges the reading list and classroom conversation away from innocence, will his students still recognize what they are reading as children’s comics? It’s not just the institution and the subject matter that insist on staying safely in the zone of the canonical…it’s frequently the students as well. So will his students resist when the reading list includes perspectives that don’t fit with the general notion of lily-White childhood? Charles asked me here only to point out his looming problems, but I feel some tiny obligation to offer some possible solutions, too. For example, when teaching the origins of comics, it might do to teach a competing theory, namely the theory that what we call comics today owes a debt to thirteenth-century Japanese art. Frankly, I don’t find that theory convincing (though I think that the influence of another Japanese art form, kamishibai, on contemporary comics has potential), but so what? Our job isn’t to teach proved, finished intellectual ideas, but to help train students to struggle with ideas on their own, and giving them a theory that mostly works will put them in the position of critiquing (or improving) it themselves. Another idea: rather than letting innocence and Whiteness be default categories, rather than letting them force us to defend any deviation from their norms, make them subjects. This is the brilliant move that feminists made with the invention of "masculinity studies": take the thing that has rendered itself invisible and make it the object of study. I’m still concerned that we’ll wind up with all-White reading lists, but this strategy allows us to observe the center without taking the center for granted. Wow, that was fun! Who knew that pointing out other people’s problems and then walking away whistling would be so liberating? Thanks for the invitation, Charles, and I can’t wait to read the posts from the upcoming comics scholars. (Up next: Dr. Gwen Athene Tarbox!) Joe Sutliff Sanders is Lecturer in the Faculty of Education at the University of Cambridge. He is the editor of The Comics of Hergé: When the Lines Are Not So Clear (2016) and the co-editor, with Michelle Ann Abate, of Good Grief! Children and Comics (2016). With Charles, he gave the keynote address on comics and picture books at the annual Children’s Literature Association conference in 2016. His most recent book is A Literature of Questions: Nonfiction for the Critical Child (2018). This post is about teaching. As I said when I started KinderComics, one of my goals in doing this blog is to brainstorm publicly about a course I'll be teaching this coming Fall 2018 semester at CSU Northridge: an English Honors seminar titled Comics, Childhood, and Children's Comics (English 392). Despite having taught at the intersection of comics and children's culture for years (including bringing comics into my entry-level Children's Literature class and designing courses on picture books that also explore comics), this upcoming Honors seminar marks the first time I've actually pitched a course devoted to children's comics per se. I'm excited about the prospect, and honestly a bit daunted by it too. Why daunted? Comics and childhood, together, make for a sprawling, complex area—and perhaps you can tell from my course's title that I haven't yet committed to a particular focus. Which is to say that I haven't decided how to delimit the course or what objectives to put front and center. I've been thinking about those things for a while. Thing is, the students and I will have fifteen weeks together, which in practice, experience tells me, means about twelve weeks tops for introducing new readings. What's more, part of the brief for an Honors seminar with, say, between a dozen and twenty students is that the students take turns presenting to and teaching one another, sharing the results of deep, self-directed research (fitting challenges for an advanced course). So it seems clear that I'll have to make some severe choices when it comes to focusing down. Yow! I've thought of at least four potential foci that are important to me:

All these areas seem important. Child characters are central to the satirical and sentimental uses of comics and to the form's popular spread; the history of moral panic is crucial to understanding comics' reputation, even now; the depiction of childhood in adult texts is key to the burgeoning alternative comics and graphic memoir canon, from Binky Brown to My Favorite Thing Is Monsters; and the sheer popularity of graphic novels for young readers today is a trend so dramatic as to throw all the other areas into a new light. So, the question for me is, what objectives do I want students to achieve as they work at the crossroads of comics and childhood? With all this in mind, I'm inviting several of my close colleagues in children's comics studies to join me here in an intermittent series of posts that I'll call a Teaching Roundtable. This roundtable will amount to, again, brainstorming, and perhaps debating the importance of our different teaching objectives. First up, TOMORROW, will be Dr. Joe Sutliff Sanders, author of, among other things, the new book A Literature of Questions: Nonfiction for the Critical Child (U of Minnesota Press, 2018), editor of The Comics of Hergé: When the Lines are Not So Clear (UP of Mississippi, 2016), and faculty member at the Children's Literature Research Centre at the University of Cambridge. Joe will be following up on this initial post -- readers, please come back tomorrow to follow and chime in on the discussion! Add your voices! Thanks.

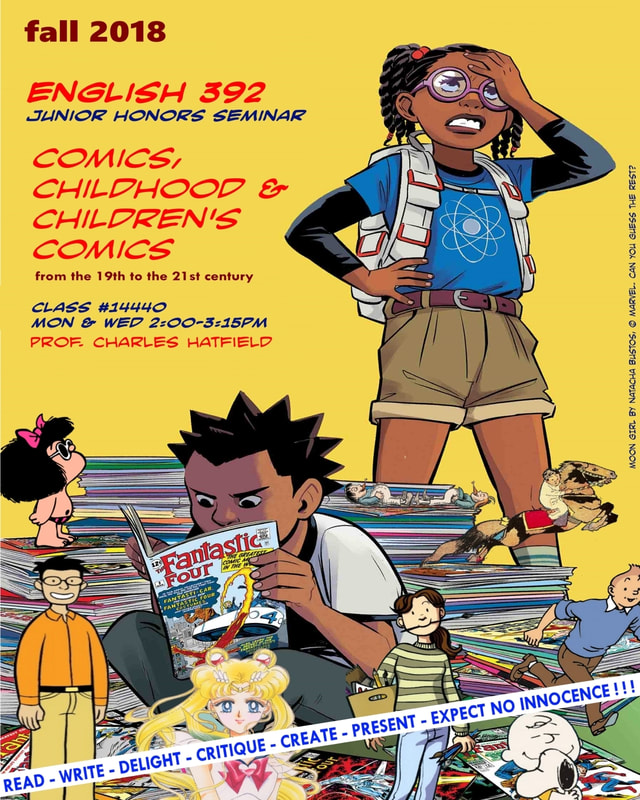

Students are just starting to enroll in my fall course, English 392: Comics, Childhood & Children's Comics -- which means that it's flyer season! I made this one by poaching, then frankly overstuffing, the cover of the recent Moon Girl #29 (Marvel, March 2018), by the terrific cartoonist Natacha Bustos. To Bustos, I added elements by Busch, Hergé, McCay, Quino, Schulz, Takeuchi, Telgemeier, and Yang, as well as a freight load of (unavoidable) text. I'm not guaranteeing that all those creators will be covered in 392, but just trying to signal the kind of range I'd like the course to have. Strictly nonprofit and educational, folks. May Bustos (and everyone else) forgive me! Starting tomorrow, in this space: the first KinderComics Teaching Roundtable!

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed