|

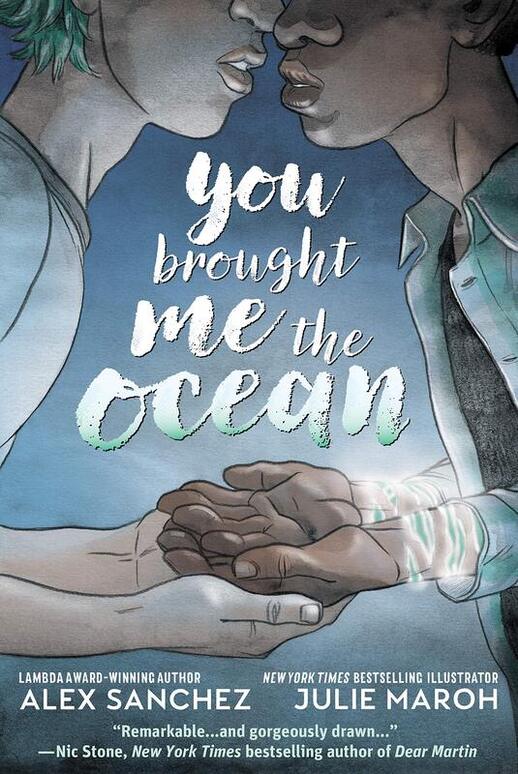

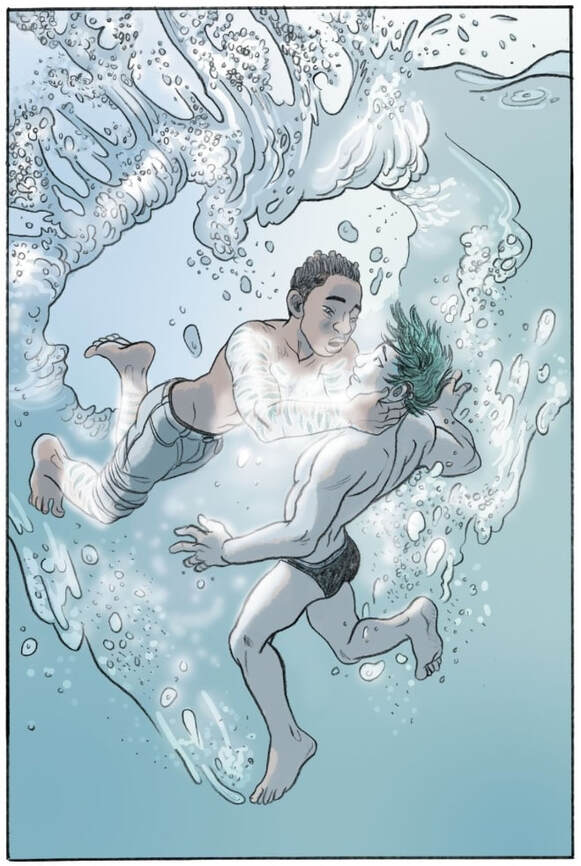

I have not been a fan of 21st-century DC Comics. Often I have criticized DC for not acting like a real publisher and for pushing more of the same ugly, self-defeating work: grim heroes, continuity porn, line-wide reboots, and other rigged and desperate moves. But nonetheless I found myself reeling from this week’s news of massive layoffs and restructuring at DC, part of a general purge at WarnerMedia (Heidi MacDonald has the best think piece on this that I’ve seen, over at The Beat). That was hard news. With DC losing a reported one-fifth of its editorial staff—indeed, as MacDonald says, “almost an entire level of editorial executives“—and the company’s publishing plans downsized, this seems like a fraught moment for comic-book culture here in the USA. I have to imagine that it’s a heartbreaking moment for many; the human cost of this sweep is considerable. It’s hard to know what to expect of DC going forward, though. Can we perhaps read some silver lining into this storm cloud? Interestingly, DC editorial will be run by two women (for the first time ever?), Marie Javins and Michelle Wells, the latter the head of DC’s Young Reader division. And, as MacDonald speculates, it seems likely that “DC’s kids and YA books will be more important going forward.” I take that as good news—but I’m afraid the news for direct-market comic book shops doesn’t sound so good (see my recent reflection on that subject here). DC Publisher Jim Lee, who remains in place after the layoffs, gave an interview to The Hollywood Reporter last Friday that puts a bright face on the changes; it seems intended to be reassuring. But I’m not reassured. (See Heidi MacDonald and Rob Salkowitz for informed readings of that interview.) I am, however, guardedly impressed by DC’s current Young Adult line, despite initial skepticism and misgivings about the work continuing to be work-for-hire in the traditional DC way. This brings me to (forgive me for pivoting so sharply) a happy review of a newish book: You Brought Me the Ocean. By Alex Sanchez and Julie Maroh. Lettered by Deron Bennett. Edited by Sara Miller. DC Comics, ISBN 978-1401290818 (softcover), 2020. US$16.99. 208 pages. (BTW, this is the third in an occasional series reviewing children’s and Young Adult graphic novels from DC. See the first here and the second here.) You Brought Me the Ocean is a smart, beautifully rendered queer YA romance in the guise of a superhero origin story, and a whole, rounded novel to boot. Despite being set in a desert town, it’s about water, about the ocean, and about learning to live as an “amphibian” in a mostly dry world. There’s something about Aquaman in it, and Superman does a distant fly-by, but, really, this story belongs to young Jake Hyde, his lifelong friend and neighbor Maria Mendez, and the young swimmer Jake falls in love with, Kenny Liu. (Jake is basically a new take on the Young Justice version of Aqualad, for those keeping track.) Kenny opens new doors in Jake’s life, just as Jake has to contemplate leaving home for college and a complex shift in his relationship with Maria. Fittingly named, Jake Hyde is closeted in several ways—in fact he is an unknown even to himself—but the story represents his coming out and coming into his own, folding together hero-origin tropes with high school and romance conventions. Loved ones and bullies alike exhibit homophobia—but, with the exception of one foul thug, the major characters all reveal unexpected depths and changeability. Characters disappoint, but then happily surprise. As Jake realizes his powers—the reason for the strange, scar-like markings on his skin—he, Maria, and Kenny become a triad of friends, and the denouement is wish-fulfilling but not pat. (There could and should be a sequel.) If Ocean revisits some familiar stuff—protective or disapproving parents, homophobic bullies repping toxic white masculinity—its characters are distinct and nuanced, and have humanizing touches. Further, the familiar stuff feels pretty convincing: these aren’t cliches so much as things that commonly happen and should be acknowledged. The book has a confident sense of its characters from the first; I can believe, for example, that Maria and Jake are longtime friends, with a shared history and personal language. Their interaction feels real enough. Scriptwriter Alex Sanchez (Lambda Award-winning author of the Rainbow Boys trilogy) handles characters and world deftly, with a smart, unforced touch. And artist Julie Maroh (Blue Is the Warmest Color) seems to know these characters’ physicality—their carriage and body language—as well as an artist could. Maroh’s figures are compact, sensual, and expressive. Most importantly, they are distinct. You Brought Me the Ocean benefits from a unified aesthetic that is unusual for DC Comics. Bathed in watery blue and silver-gray, and then again in muted desert browns and tans, the book enacts the major conflict in Jake’s life through its very palette. Thanks to Maroh and designer Amie Brockway-Metcalf, it boasts a visual wholeness and integrity that set it apart. Subtle yet dynamic layouts, unhurried pacing, and mostly understated action define the book, which sidesteps epic superhero dust-ups in favor of smaller, though still dramatic, discoveries. That said, the art remains ravishing; Maroh’s individualized figures and muted colors cast a spell even as they do the vital work of characterization. This appears to have been a harmonious, lovingly edited collaboration; it’s a remarkable feat for a first-time team. As I said, I’d read more. You Brought Me the Ocean is YA superheroics done with grace and a sensuous visual language. In fact, it’s only a superhero story on its edges; fluency in the DC Universe is not required. At heart, it’s an affirming story of love and friendship with a fantastical, magic-realist touch. Recommended! PS. KinderComics is taking a roughly six week-long break, sigh, so that I can start the new semester at CSU Northridge more or less sanely. See you in about a month and a half!

1 Comment

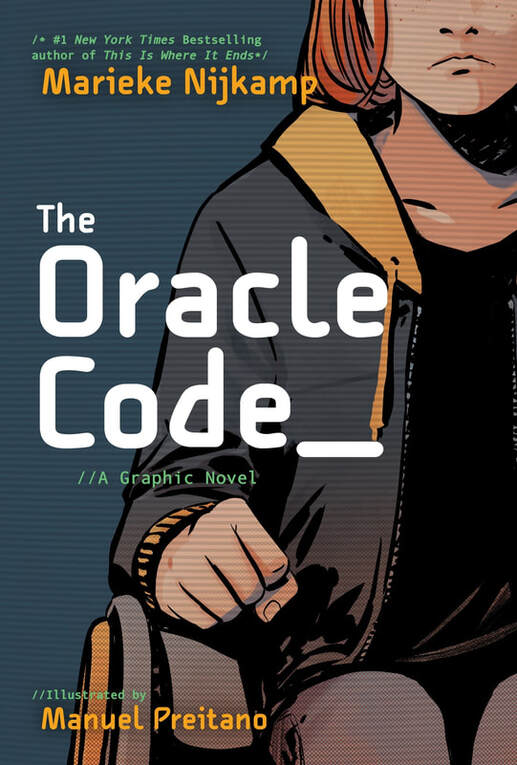

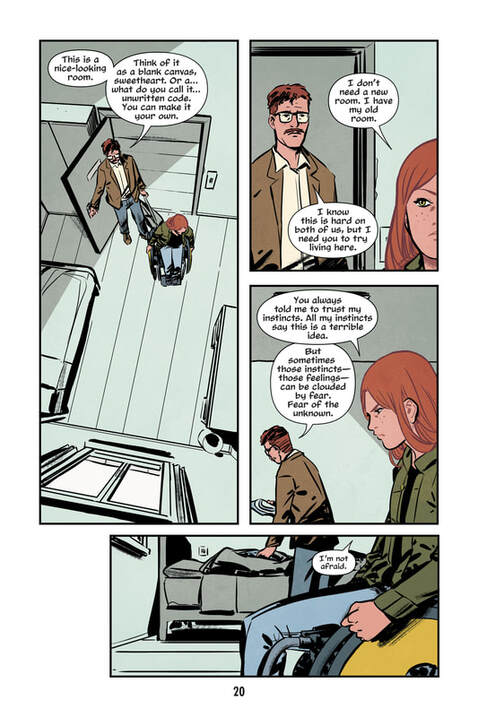

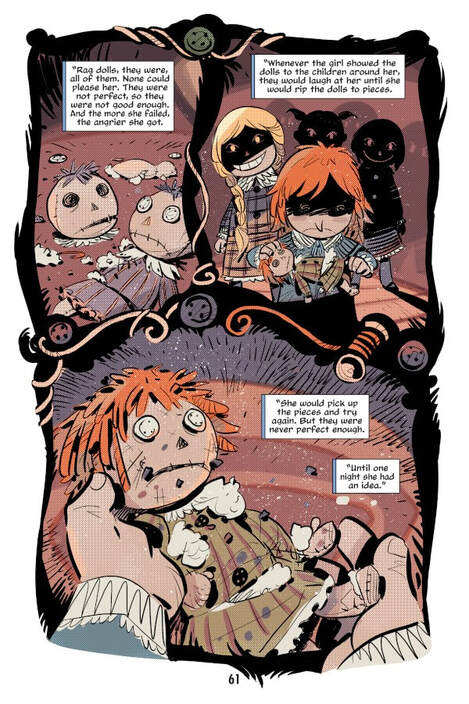

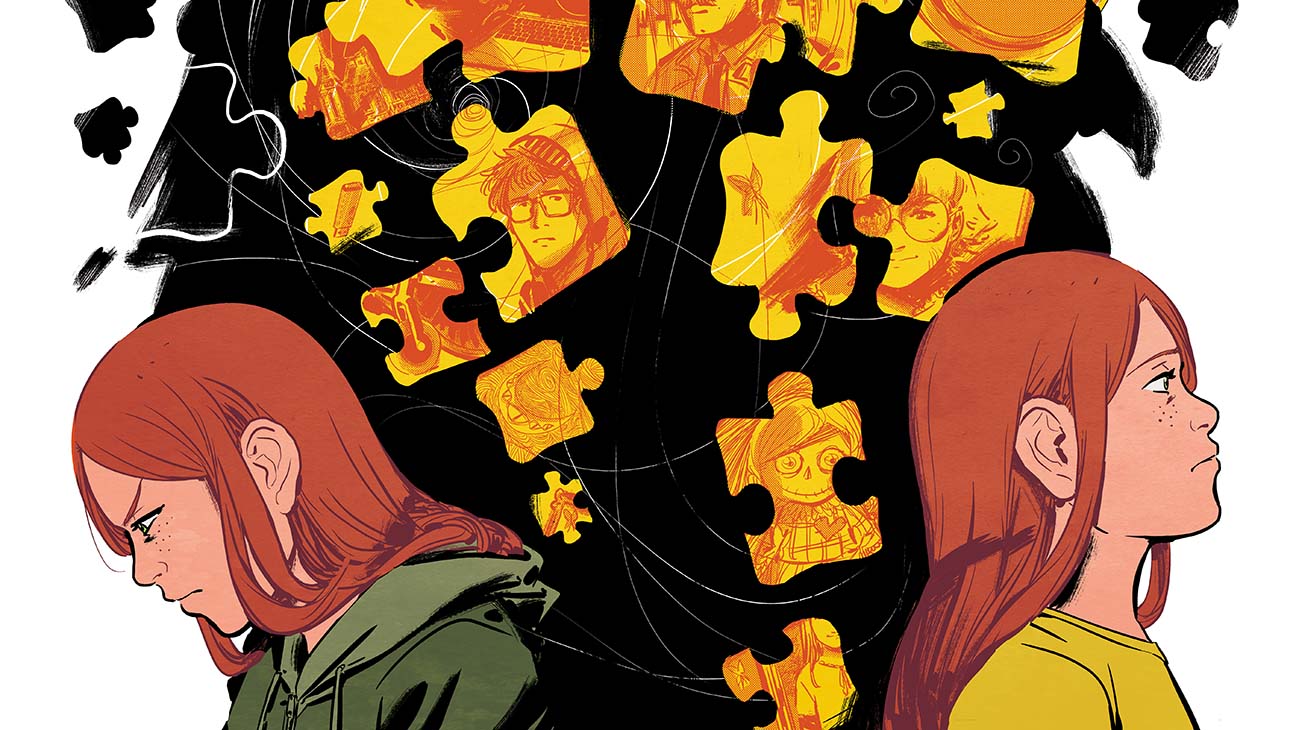

The Oracle Code. Written by Marieke Nijkamp; illustrated by Manuel Preitano; colored by Jordie Bellaire with Preitano; lettered by Clayton Cowles. DC Comics, ISBN 978-1401290665 (softcover), 208 pages. US$16.99. March 2020. (This is the second in an occasional series reviewing children’s and Young Adult graphic novels from DC. See the first here.) Paralyzed by a gunshot wound, brilliant young hacker Barbara Gordon (daughter of Gotham’s police commissioner) undergoes rehabilitation at the so-called Arkham Center for Independence — which, surprise, turns out to be a sinister place, a haunted house even, from which patients keep disappearing. Though traumatized, and at first resentful and alienated, Barbara gradually bonds with other patients, and together they form a team to unravel Arkham’s dark secret. This DC graphic novel does not appear to mesh with any version of DC continuity, and its Barbara Gordon differs sharply from previous Barbaras (Batgirl or Oracle). In fact, its DC-ness is nominal, and could be erased with a few minor edits. It’s not a superhero story in the usual sense. Rather, it’s a Young Adult thriller that follows many of that genre’s conventions: young people up against corrupt adult institutions, fighting with official powers, fighting for self-definition, testing their mettle with no outside help. It’s also grounded in an intersectional and community-oriented disability politics that makes it stand out among DC books. Writer Marieke Nijkamp is an acclaimed author of YA thrillers (e.g., This Is Where It Ends), editor of a disability-themed YA anthology (Unbroken), and advocate for greater diversity in children’s and Young Adult publishing (she served as a founding officer of We Need Diverse Books). The Oracle Code’s plot seems to have been informed by her experience living in a medical rehabilitation facility as a teenager. Her loner hero, Barbara, eventually enters into community, and, with her team, emphatically rejects the idea of being “fixed” (echoing Nijkamp’s criticisms of the trope of curing disability). The book’s politics are obvious and central, and some minor characters and relationships seem designed to make points — or to serve merely as hurdles to Barbara’s ferocious drive. The plot, I think, rushes to a too-sudden conclusion; I can see the story’s somewhat familiar shape from far off. Barbara herself, though, is a distinct character, and the book gives her time and space to be properly angry. If the book preaches, it doesn’t preach to Barbara. Also, the wrap-up wisely lets certain resolutions stay ambiguous; this is no facile overcoming narrative in which all things are made better. The book reflects on the healing value of dark stories — through a series of unsettling embedded tales, like bedtime stories — and itself does not shy away from trouble. The Oracle Code, in sum, is a designedly Young Adult novel that reflects and capitalizes on the disability politics always implicit in the Oracle character. Visually, The Oracle Code wavers between arid daytime plainness — perfect for a medical facility — and darkly atmospheric nighttime scenes. Illustrator Manuel Preitano favors a naturalism that, for me, recalls the post-Mazzucchelli work of David Aja (though without Aja’s drastic stylization and formalist invention). The intentionally limited color palette (colors are credited to both Jordie Bellaire and Preitano) pits vivid yellow-orange and nocturnal purple-blue against drab olive and icky, hospital-bland greens. Insipid, textureless rooms — like the flat, medicalized interiors we all know, presumably lit by fluorescents — clash with densely shadowed scenes defined by slashing swathes of black and vigorous dry-brush technique. Bright jigsaw puzzle pieces stand out against the general gloom and serve as a braided visual device: a multivalent symbol that variously signifies trauma, fragmentation, reassembly, accomplishment, and, of course, mystery-solving. The layouts are dynamic, shifting, yet steadily rectilinear, except for the embedded “bedtime” stories, which boast curving, swirling panel shapes and a contrasting, cartoonish style. This novel is, as far as I know, Preitano’s longest sustained work for the US market (he has also worked on the series Destiny, NY and several comics for Zenescope), and departs from the sometimes lurid retro aesthetic of his illustrations for the Vaporteppa fiction line, in his native Italy. This looks like a big step forward for the artist. On balance, The Oracle Code shows the potential of YA fiction that happens to be set in DC’s story-world. It’s more self-contained, and more attuned to the conventions of YA fiction, than I had expected. To me, these are good things. One thing gets to me, though: despite the signs that this book is a rather personal work for Nijkamp, it is copyrighted solely in the name of DC Comics — that is, it’s work for hire (though it bears about as much resemblance to prior Oracle stories as, say, Neil Gaiman and company’s Sandman bore to prior Sandmen). I think that’s a shame, and, honestly, this is one reason I have not been able to muster great enthusiasm for DC’s work with YA and children’s authors. As long as DC graphic novels are centered on company IP and the creators are wholly dispossessed of any equity in the work, as long as DC persists in these damaging comic book industry practices, the promise of its young readers’ line will be dampened. The Oracle Code is very unusual for a DC comic — its focus on a non-superpowered community of young women, and willingness to highlight a young woman’s anger and power, are laudable — but it’s still shackled to DC’s old way of doing things.

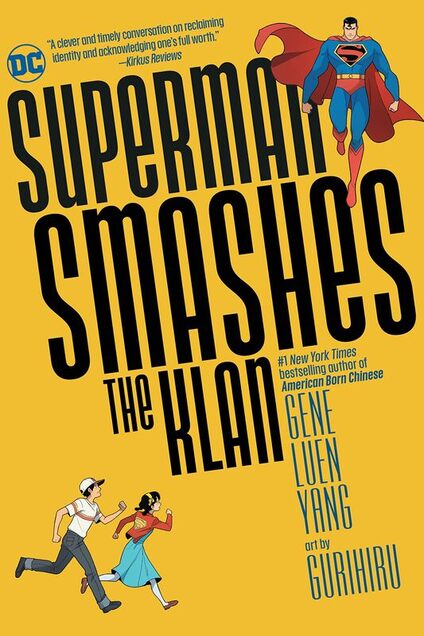

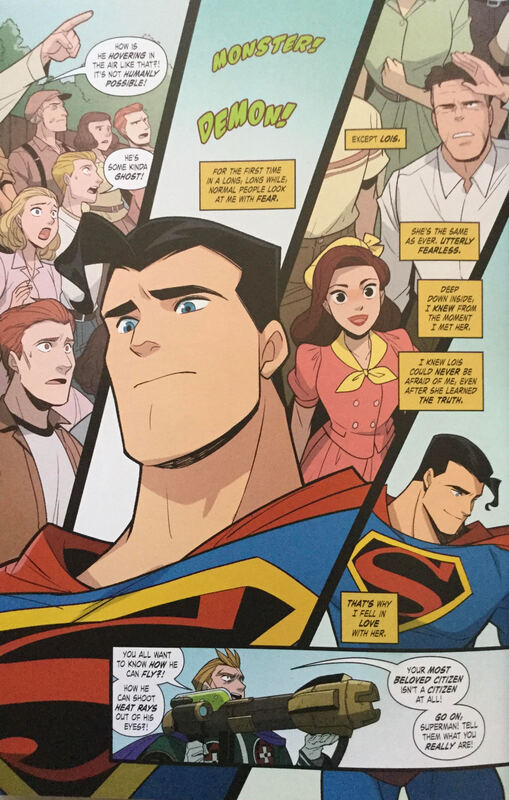

Superman Smashes the Klan. By Gene Luen Yang and Gurihiru. Lettering by Janice Chiang. DC Comics, ISBN 978-1779504210 (softcover), May 2020. US$16.99. 240 pages. (The first in an occasional series reviewing children’s and Young Adult graphic novels from DC.) One of the pleasures of reading Gene Luen Yang is watching him play — and take risks — with sources. American Born Chinese gives the Chinese literary classic Journey to the West an Americanized (and Christianized) spin, while riffing on sitcoms, Transformer-style mecha, and Yang’s own boyhood as an immigrant’s son. The recent Dragon Hoops (reviewed here in March) folds the history of basketball, reverently sourced, into its account of Yang’s last year as a high school teacher. Yang’s five-volume run on Avatar: The Last Airbender (2012-2017), his first collaboration with Japanese art team Gurihiru (Chifuyu Sasaki and Naoko Kawano), is a sequel to the beloved TV series (2005-2008). The Shadow Hero, Yang’s 2014 graphic novel with artist Sonny Liew, revives an obscure Golden Age superhero, Chu Hing’s Green Turtle (1944-1945), giving him a new origin and feel. Yang’s latest, Superman Smashes the Klan (now gathered into one volume, after a three-issue serial release last year), draws from an antiracist storyline in the Adventures of Superman radio serial in 1946, but adapts it freely. Superman Smashes the Klan interweaves several threads from Yang’s previous work. Once again, he plays with DC Comics and Superman lore; again, he collaborates with Gurihiru. Once more, as in The Shadow Hero, he treats the superhero-with-secret-identity as an overt assimilation fantasy, in a period American setting. It’s the best of his DC projects by a long shot: the most obviously personal, the most graphically whole, consistent, and readable. It’s also, I think not coincidentally, the one that comes closest to the children’s and YA graphic novel genre that Yang is best known for. This is one of the more interesting of the many 21st-century reinterpretations of Superman’s origin. It happens that my wife and I have been reading it at the same time as another reinterpretation, Tom De Haven’s prose novel It’s Superman! (2005). De Haven’s is a free retelling of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster’s original, late mid-1930s Superman, done up as nerdy, name-dropping historical fiction in the vein of Michael Chabon’s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay (2000). It’s Superman! digs hard into that vein, stressing economic misery, political unrest, migration, segregation, and pervasive everyday racism in tune with its Depression-era setting. Also, it’s peppered with cameos by real-world people, neighborhoods, architecture — you name it, De Haven has researched it. Add in sexual knowingness, lurid violence, and odd character studies of crooks and victims, and you’ve got a very “adult” riff on the Siegel and Shuster model, something not too far from De Haven’s other comics-themed historical novels. Don’t get me wrong: It’s Superman! is a terrific book, one I’d like to teach when I get around to doing an all-Superman course. I think it would teach well alongside Superman Smashes the Klan, as both replay Superman’s origin in early 20th-century period (the mid-30s for De Haven; 1946 for this book) — and both stress Clark Kent’s moral education, his growing awareness of social injustice. Yet the two books are quite different. De Haven’s Clark never finds out where he came from; though he suspects that he is not from Earth, he never learns about planet Krypton. The book only hints at Clark’s origins. De Haven works hard to suggest how this lonely, alienated young man might turn to reporting, and to his unrequited love for Lois Lane, as a way of becoming “just like everybody else.” Yang and Gurihiru’s Clark, on the other hand, learns more about his extraterrestrial origins — there’s more SF in his story. He too, though, longs to be like everyone else, to assimilate — so much so that he hides his light under a bushel, downplaying or even failing to recognize some of his powers. He befriends young Roberta and Tommy Lee, children of a Chinese immigrant family that has just moved to Metropolis, and combats a militant, White supremacist Klan group that terrorizes them. At the same time, he must confront his fears of revealing his own alienness, and frightful visions of himself and his birth parents as green-skinned monsters. This Clark starts out not knowing about Krypton, but gradually learns of it (through a familiar plot device: a bit of leftover Kryptonian tech). In the course of fighting the Klan, Clark discovers the full extent of his powers, hidden from him by his own desires to assimilate: a clever way to explain how the running and jumping Superman of early Siegel and Shuster became the flying Superman with X-ray vision that we know now. But much of the story belongs to young Roberta (Lan-Shin) Lee, whose worries about fitting in mirror Clark’s, and whose empathy with him proves key to unlocking his potential. Yang and Gurihiru give us brief flashbacks to Clark’s origin, while focusing on his anxious way of passing among humans in the present — an anxiety Roberta knows all too well. The book's nonlinear retelling deftly frames the old origin story as a fable of assimilation (à la The Shadow Hero). Roberta and Clark, both immigrants uncomfortably aware of their alienness, together foil the Klan and stand up for a vision of Metropolis — implicitly of America — in which everyone is “bound together,” sharing the same future, “the same tomorrow.” In this way, Superman Smashes the Klan makes its antiracist parable integral to Superman’s own process of becoming. Superman Smashes the Klan is not subtle; after all, it’s a value-laden fantasy of nation, like so many American superhero comics — and it obviously courts a young audience (Young Adults, says the back cover, but I’d say middle-grade). The book wears its values on its sleeve. Also, the period setting seems idealized: for example, Inspector Henderson of the Metropolis PD is here portrayed as African American, which tends to suggest a very progressive Metropolis for 1946, one in which the Klansmen’s anti-Black racism makes them outliers. This may be too easy. Though the story acknowledges that racism takes many forms, the masked Klansmen provide an obvious, simplistic focus (I’d expect a YA novel about racism to be more ambiguous and challenging on this score). On the other hand, the book allows some of its racist characters to grow: young Chuck, nephew of the Klan’s leader, learns to reject his uncle’s ways at the boffo climax — at which a bunch of kids help Superman save the day, own his identity, and face down xenophobia. Superman Smashes the Klan, then, dares to hope — as children’s texts so often do — that the openness and innocence of the young can redeem a society riven by bigotry and corruption. This utopian vision is familiar to anyone who studies children's literature; it's obvious. Yet, obvious or not, this is just the kind of Superman story I prefer to read, one in which Supes clearly stands for a decent, humane, inclusive ideal. It’s on the nose, sure, but that doesn’t bother me much. It could make a terrific animated film, in post-Spider-Verse mode (we can only hope). That said, Superman Smashes the Klan is not as effective, I think, as Yang and Liew’s Shadow Hero, which more daringly uses superhero tropes to create a layered, ambivalent assimilation story. This is a Superman comic, after all, hence constrained; the nervy, potentially offensive gambits in The Shadow Hero are not to be expected. Yet Yang has taken some interesting risks in reworking Superman’s origin; it’s good to see the truism that Superman is an immigrant being put to real use. It’s likewise good to see Superman sprung free — liberated — from the suffocating weight of “DC Universe” continuity. I'm a little sad that this has to happen in a distanced period setting, rather than a contemporary one. (I'd love to see this book spawn a series of timely, obviously relevant Superman GNs set in the present day, for the same audience.) Stylistically, I’ll say that I find the book a bit too clean and antiseptic to conjure the desired sense of period; Gurihiru’s neat, smart artwork strikes me as too textureless and bland to evoke a mid-1940s Metropolis. I’d have liked to see a grittier city setting, with more grimy particulars, so that Superman’s bright, heroic doings would stand out by contrast. On the other hand, Gurihiru’s pages are dynamic, inventive, and ever-readable. The book combines the snazziness and roughhousing energy of most superhero comics with clear-line legibility. It’s fetching and fun to look at, and Yang and Gurihiru are clearly sympatico (their Avatar collaboration obviously prepared them for this). If only most DC comics were this free and confident of their aims. The recent news that Marvel is teaming up with Scholastic — that is, licensing Scholastic to produce a series of original graphic novels for young readers starring Marvel heroes, to be published under the Graphix line — gives me hope that we may see a flood of comics with similar aims. That announcement came as a surprise, but perhaps it shouldn't have: after all, young readers' graphic novels are the thriving sector in US comics publishing today. Maybe, just maybe, US-style superhero comics, not just movies, TV shows, and goods based on such comics, can once again become popular, widely available children's entertainment. Having lived through (and, for a time, invested emotionally in) the revisionist adultification of superheroes in the 1980s to 90s, I find this prospect oddly exhilarating. I wonder what Yang thinks — and if he is keen to do more books of this type. Man, what I wouldn’t give to teach a sequence like so: Siegel and Shuster’s first two years of Superman (1938-1940), De Haven’s retake, The Shadow Hero, and Superman Smashes the Klan. I bet that would kick off some great conversations. PS. Gene Luen Yang has been on the board of the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund since 2018. In light of the infuriating recent news out of that troubled organization, his frank and reflective remarks on Twitter have been illuminating. Yang — wisely, I think — values the Fund's mission over the current organization, while also pointing out the good work done by current CBLDF staffers. It's quite a tightrope walk — and recommended reading for those who've been following the news of the CBLDF, and the comic book field's larger sexual harassment and abuse crisis, on this blog. PPS. Gene Yang is slated to take part in three virtual panels at this week's Comic-Con@Home: The Power of Teamwork in Kids Comics (today, Wednesday, July 22); Comics during Clampdown: Creativity in the Time of COVID (Thursday, July 23); and Water, Earth, Fire, Air: Continuing the Avatar Legacy (Friday, July 24). These events, like most panels making up Comic-Con@Home, will presumably be prerecorded, hence without live audience Q&A, which is a shame. But, still, there should be some interesting back-and-forth among the panelists, and Yang is a great ambassador and thinker on the fly. See comic-con.org or Comic-Con's YouTube channel for further info.

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed