|

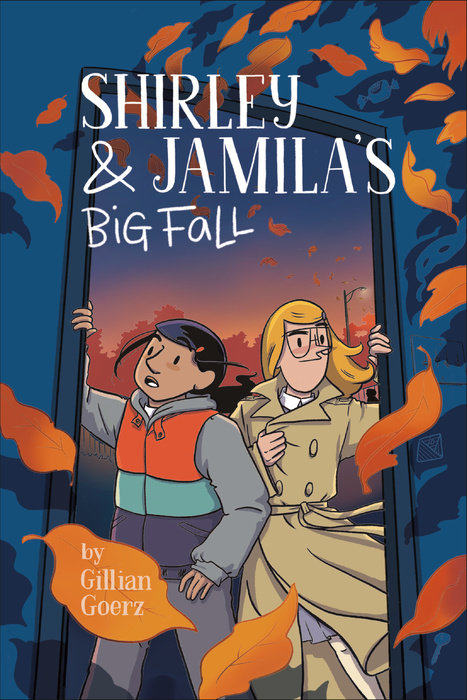

Shirley & Jamila’s Big Fall. By Gillian Goerz. Color flatting by Mary Verhoeven. Dial Books, 2021. ISBN 978-0525552895, US$12.99. 240 pages. The first comic I read in 2022! I read it on January 1. I thought I'd break out of my self-imposed hiatus to write this quick review: More complicated and less charming than the first Shirley and Jamila book (which I reviewed almost exactly a year ago), this one adapts a Sherlock Holmes tale by Conan Doyle into a somewhat incredible middle-grade story of bullying and comeuppance, one in which Shirley and Jamila commit burglary and break a lot of rules in order to solve a nasty problem for everyone at their school. I admire the book’s emphasis on kids’ agency and cleverness — adults don’t solve the problems here, kids do — but the resulting story is hard to believe. Essentially, Goerz has taken up an Edwardian thriller, in which the blackmailer gets his just desserts at the point of a revolver, combined it with familiar middle-grade tropes about the excitement and anxiety of a budding friendship, and then tried to engineer a nonviolent, affirming, and progressive payoff. I didn’t quite buy it. The Shirley and Jamila books recast the Holmes and Watson relationship with two middle-grade girls, the White, Anglo-Canadian Shirley Bones and the Pakistani Canadian Jamila Waheed. Goerz portrays contemporary Toronto as a welcoming multiethnic community and promotes an ethic of inclusivity and diversity. The first book, Shirley & Jamila Save Their Summer (2020), is about a theft, but the thieves turn out to be relatable and redeemable characters, and the book becomes a paean to tolerance and understanding. This second book, however, has an out and out villain, one who isn’t quite humanized and certainly not redeemed. He is, tellingly, a rich White boy who epitomizes privilege. This villain seeks to hide his insecurity by gathering secrets, blackmailing his classmates, and turning them against each other. Masking his aggression with smarm and false concern, he is an abhorrent character, loathsome through and through. Of course, Goerz can’t have him shot at point-blank range, à la Conan Doyle, but she has to defang him somehow. This is where the book’s secondary plot about friendship comes in, as a new friend of Jamila’s becomes the means of his undoing. In essence, Goerz introduces a new character into Jamila and Shirley’s friendship dyad, testing their connection to each other, while trying to convert Conan Doyle’s tale of a blackmail victim’s revenge into something more positive. Along the way, the story skirts moral complexity, justifying questionable decisions made by Shirley and Jamila in the pursuit of justice. The original Conan Doyle story endorses vigilantism (key to Holmes's appeal) and excuses Holmes’s deceptive tactics, spying, and use of disguise and feigned friendship in the name of a higher good; these same moves look strange when committed by a fifth-grader. Again, I didn’t buy it. So, I have my doubts about recasting Holmes and Watson, originally 19th-century British men of fortune, as contemporary school kids in a progressive milieu. This second book stirs up those doubts. Its plot-rigging is, again, hard for me to believe, and the Jamila/Shirley relationship isn’t helped by Shirley’s Holmesian habits of secrecy and spying. The resulting mix is unsteady, with Goerz working hard to foreground Jamila's perspective but Shirley upstaging Jamila with her eccentric, Holmes-like brilliance and cool scheming. That said, this is a briskly cartooned, inventively laid-out graphic novel, more visually dynamic than its predecessor. The story’s highlight is the extended, multi-chapter burglary carried out by Shirley and Jamila, a sort of tightly wound heist sequence that takes up a good 90 pages. This is exciting stuff, a tense, precisely staged caper (I imagine that Goerz relished the challenge of staging it). I have to admit, I expected more serious moral repercussions afterward, and I’m disappointed that Goerz didn’t push the hard questions, but there are some nice, suspenseful moments along the way. I hope Goerz will do further Shirley and Jamila books, though I also hope that she doesn’t pattern their stories so closely after Conan Doyle — her characters and milieu seem to call for something else.

0 Comments

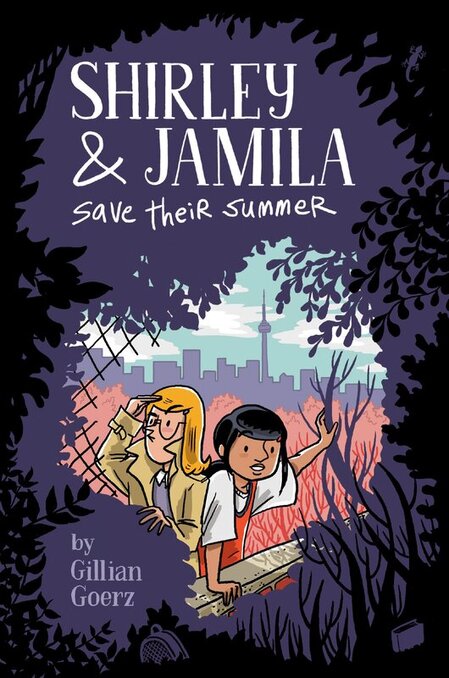

First, a brief personal note:You might think that being in pandemic lockdown would mean reading lots of comics, and with relish. I had thought so too. But I have to confess to feeling adrift lately; if anything, I may have been reading fewer comics than usual. I frankly don’t understand this, and it makes me sad, but there it is. COVID seems to have wrought havoc with my reading life, and many of the talked-about comics of 2020 are still unknown to me. Usually, I look back on the year in comics with a surplus of terrific new titles that I have trouble choosing among. Bounty is my normal. This year, though, I've had a hard time envisioning a Best-Of list for KinderComics. I've been down in the dumps about this for a bit. That's why it is such a pleasure to have contributed, in however small a way, to SOLRAD's list of The Best Comics of 2020. This multi-authored listicle is an education to me: a reminder of how widespread, diverse, and unpredictable comics can be. SOLRAD, "a nonprofit online literary magazine dedicated to the comics arts," has just celebrated its first anniversary, and it's a great site, an essential stop for readers who care about innovation and artistry in comics. I'm glad to have done anything for them, and very glad to have their Best-Of list as an antidote to my blues. Please go check it out! And now, back to what KinderComics usually does: Shirley and Jamila Save Their Summer. By Gillian Goerz. Dial Books, 2020. ISBN 978-0525552864, US$10.99. 224 pages. I like this sunny middle-grade mystery, which follows a pair of mismatched but true friends who investigate a theft at a local swimming pool. It’s the sort of thing that could hit the spot for fans of Nancy Drew, Encyclopedia Brown, or Nate the Great. The setting appears to be suburban Toronto. Shirley is a super-observant Holmesian kid detective, also a social outcast: a tightly wound nerd-savant figure, perhaps implicitly an Aspie (the characterization seems to lean in that direction). Jamila, the novel’s true focal character, is an aspiring athlete, eager and restless, loved by her family yet perhaps overshadowed by her older brothers. Jamila and Shirley, temperamental opposites, need each other; both girls chafe against the protectiveness of their moms and are looking for ways to buy a bit of freedom over the summer. They team up to break out. Shirley is White, while Jamila comes from a South Asian, perhaps Afghan or Pakistani, ostensibly Muslim family; the girls' neighborhood is convincingly diverse. We learn much about Jamila’s family, the dynamics of which are deftly established, with discreet cultural cueing and an easy, lived-in complexity. (I particularly liked the characterization of her mother, a subtle and telling depiction.) Despite some early signs of tentativeness (say, in layout and balloon placement), Goerz crafts a tightly constructed, unflagging, engaging story, one that hopscotches confidently from chapter to chapter, evokes a credible social milieu, and, best of all, vividly imagines what turns out to be a large repertory company of characters. This is, in the end, a sure-handed, well-edited, handsomely cartooned first graphic novel for Goerz: in sum, a cool book. It looks to be the first volume in a projected series; I'd happily read more.

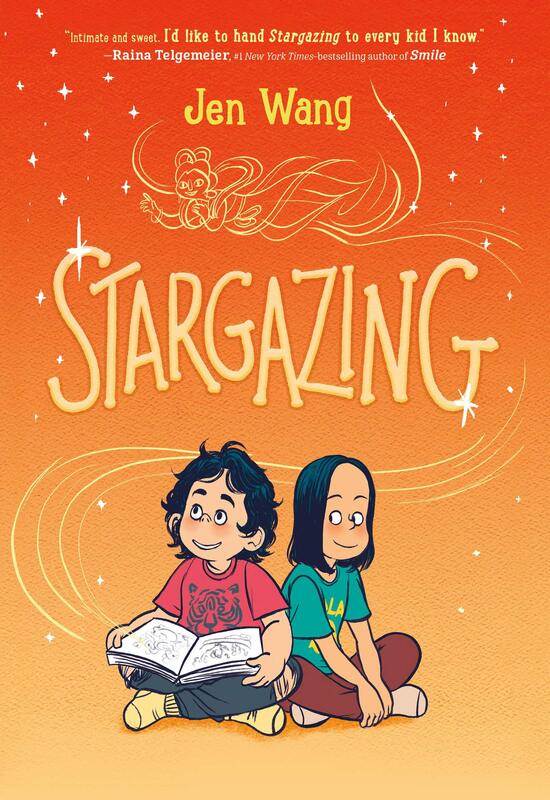

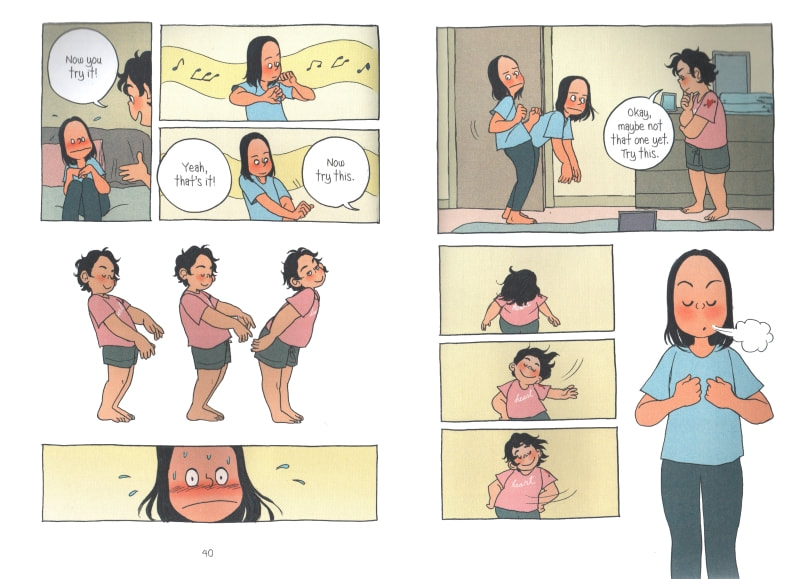

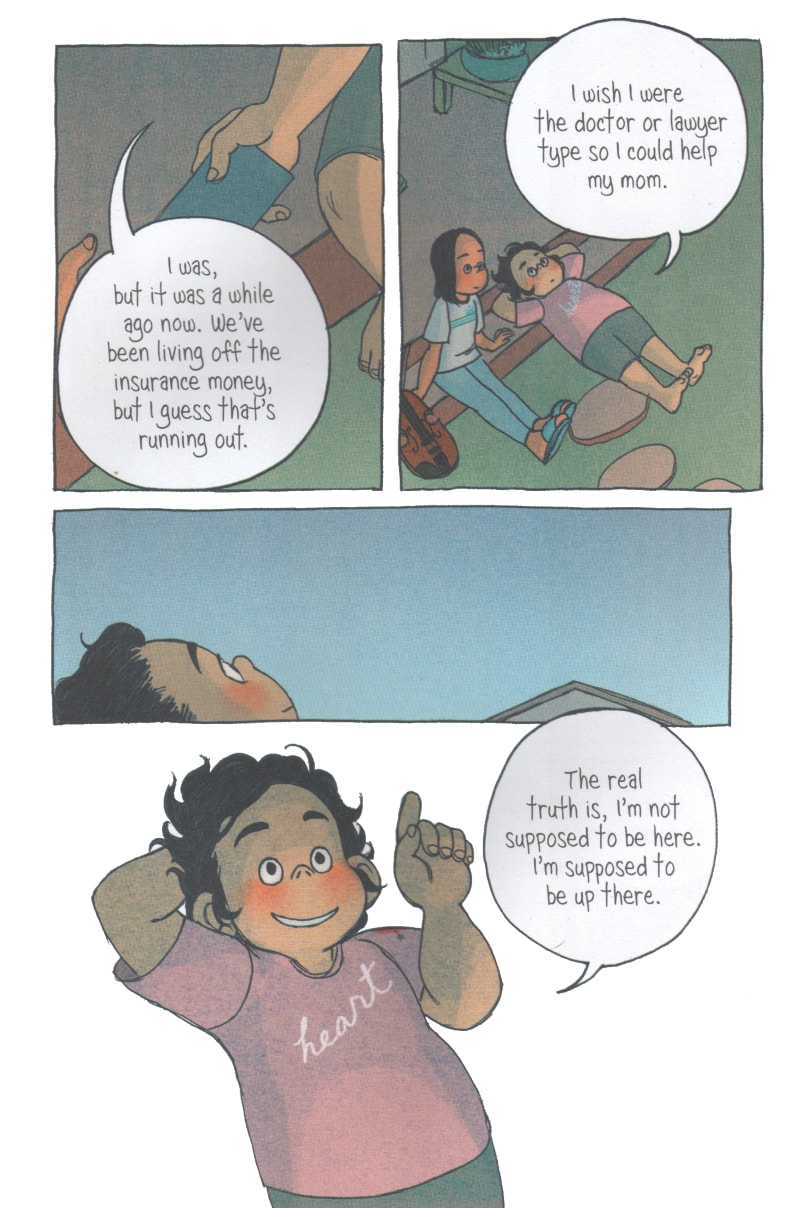

Stargazing. By Jen Wang. Color by Lark Pien. Song lyrics by Hellen Jo. First Second. ISBN 978-1250183880 (softcover), $12.99; ISBN 978-1250183873 (hardcover), $21.99. 224 pages. Stargazing, Jen Wang’s follow-up to last year’s The Prince and the Dressmaker, is recognizably by the same artist—one of America’s best comics artists. Yet it’s a very different sort of book. A middle-grade graphic novel about friendship and jealousy among girls, it falls squarely into Raina Telgemeier territory: a school story about finding your complementary opposite and becoming friends, but then pulling back, but then stepping forward again. As it traces a relationship between two girls, Christine and Moon, Stargazing evokes the camaraderie and intimacy of friends sharing secrets. At the same time, it registers how selfishness and anxiety may complicate our friendships. Wang treats small betrayals among school friends as the stuff of moral drama. In particular, she pays attention to what it may mean to be an immigrant’s daughter driven by certain dreams of success, and how such a driven child might look to another girl, one far from her in class and temperament, for a kind of relief, a liberating counter-example of a life lived more freely or less anxiously. But of course that “other” girl has complications of her own. Along the way, Wang conveys differences of class and circumstance within a Chinese American community, showing how adaptation and resistance may take diverse forms. Building on her own memories of girlhood, and detailing how different families may cleave to different standards and impose different pressures, Wang fashions a portrait of community and an understated story of girlhood friendship with a very particular cultural setting. In short, this is a terrific book. Female friendship is a, or maybe the, abiding theme in post-Raina graphic Bildungsromane. I’ve noticed various author-artists tacking in that direction (KinderComics readers may recall, for example, reviews of Larson’s All Summer Long or Brosgol’s Be Prepared). At the recent PAMLA conference in San Diego, scholar Erika Travis (California Baptist University) presented on this very topic, drawing on Jamieson’s Roller Girl, Bell’s El Deafo, and Hale and Pham’s Real Friends for examples. She showed how these books stake out the traditional concerns of girls’ middle-grade books, only in comics form. Stargazing leans in that direction too—it’s the simplest, most grounded of Wang’s books, harking back to the slice-of-life of Koko Be Good but framed as a school story. Thematically, it invites comparison to Telegemeier’s recent Guts; for example, in both books characters use their art to cement relationships. Stargazing, though, shoulders the added complexity of immigrants’ children in a specific Chinese American context. Its protagonist is weighed down by her father’s aspirations for success—perhaps an oblique commentary on the model minority myth—and this complicates, almost undermines, her friendship with her complementary opposite. Christine, studious, high-achieving, and serious, contrasts sharply with her new neighbor Moon, impetuous, high-spirited, and hyper. The former is quiet and restrained, and driven to academic success—partly by her well-meaning but at times insensitive father. The latter is a spitfire: bright and scattered, cheerfully defiant of rules, and prone to cold-cock other kids who are mean to her friends. Christine is the idealized academic success, Moon the subject of nervous gossip. Christine’s family is well-off; Moon’s single mother struggles to make ends meet. When Moon and her mother move into the guest home rented out by Christine’s family, the two girls strike up an unlikely friendship, and Moon’s energy rubs off on Christine, whose reserve begins to melt a bit. Moon introduces Christine to K-pop and dance. Christine’s family introduces Moon to Chinese language class (but it doesn’t take). The two bond, in a series of delightful scenes. Moon confesses to Christine her belief that she, Moon, is not an ordinary Earth girl but rather a creature from the stars—that one day she will return to a home on high. Sharing this with Christine is a gesture of friendship. Christine, though, prompted by anxieties about academic success and social approval, backs away from that friendship. A small betrayal bumps up against a major crisis, as Moon has to face a serious, life-altering event—and Christine, dogged by guilt, has to own her past behavior and, somehow, move forward. She struggles. She hides. But hiding can't last forever. This outwardly simple plot is treated with the utmost delicacy, and a great many insinuating cultural details that enrich the context. More to the point, its resolution is moving: every time I reopen the book I get choked up. Wang is that good. While Stargazing may be in, broadly speaking, familiar territory, it isn’t generic at all. It seems to be a dialogue around Chinese American experience and different ways of being a Chinese American girl. It evokes specific familial and communal settings with a brilliant economy. At the same time, it’s aesthetically gorgeous: Wang’s cartooning and layouts boast an elegance and lightness of touch that are rare. The book’s use of negative space—of unenclosed figures and the whiteness of the page—gives it a free-breathing, eminently readable quality. The same delicacy with character and emotion seen in The Prince and the Dressmaker comes through here, abundantly; Wang knows how to capture the finest nuances of expression. This is simply first-rate comics—and highly recommended.

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed