|

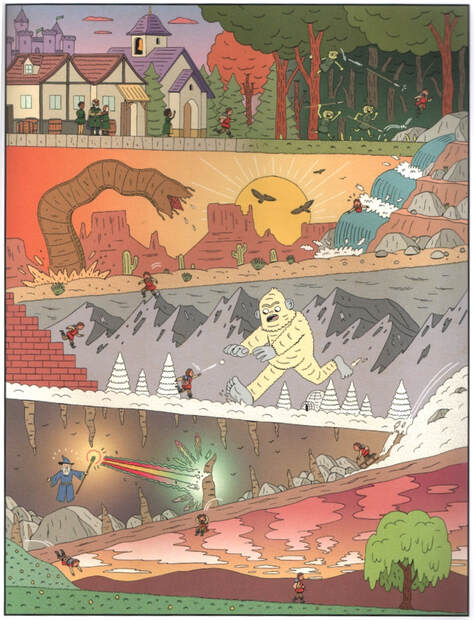

Paul Bunyan: The Invention of an American Legend. Comic by Noah Van Sciver, plus essays and art by Marlena Myles, introduction by Lee Francis IV, and postscript by Deondre Smiles. TOON Books, ISBN 978-1662665226, 2023. $US17.99. 52 pages, hardcover. Paul Bunyan: The Invention of an American Legend is another TOON Graphic that juxtaposes a compelling comic with carefully curated (front and back) editorial matter. In this case, the introduction and back matter are not just instructive supplements but pointed rejoinders to the comic, and essential to the book's overall effect. Noah Van Sciver's comic takes up 36 of the book's 52 pages, but the remaining pages are emphatically not filler. What we have here is a package that both burnishes and yet undermines the "legend" of the faux-folkloric lumberjack, Paul Bunyan, with Van Sciver casting a skeptical eye on how the legend was promulgated while the other features remind us of what the legend hides. It's a great and startling project. I wish it had been among the Kids nominees for this year's Eisners, and was glad to see it among the finalists for this year's Excellence in Graphic Literature Awards (which is what reminded me to write about it here). Noah Van Sciver has become one of my favorite cartoonists. He is a terrific humorist and memoirist (his hilarious autobio comic, Maple Terrace, was one of my favorites from last year). What's more, he is one of the US's best and most prolific creators of historical and biographical comics (his brave book Joseph Smith and the Mormons is just the iceberg's tip). Paul Bunyan feels like it's right in his wheelhouse. The story, a fiction inspired by fact, takes place in Minnesota in 1914 on a westbound train, as lumber industry ad man William Laughead regales his fellow passengers with yarns about Paul Bunyan, "the best jack there ever was" and the epitome of the industry's clear-cutting zeal. Laughead's crazy, mythmaking anecdotes have the zestful absurdity of tall tales, and Van Sciver knows how appealing such tales can be. A shameless fabulist, Laughead imagines Bunyan as an unstoppable giant-sized version of himself. He meets challenges posed by skeptical listeners with a game face and ever-escalating bunkum. Van Sciver portrays him as folksy, funny, a bit desperate, and basically a shill. More critical perspectives are provided by other characters, especially a disillusioned lumber industry vet. The art is lively and joyous, but also insinuating, and the textures (drawn in ink but then colored digitally) are trademark Van Sciver. This is beautifully organic and readable cartooning. You could say that this is Van Sciver's project (the indicia assigns the copyright to him and TOON), but the elements provided by other creators are vital. Those elements, from Native writers and artists, decry the "seizure of homeland" and environmental devastation spurred by America's rapacious lumber industry, and champion forms of history and knowledge obscured by the aggressive expansionism of the Bunyan myth. Lee Francis IV (Pueblo of Laguna), well-known as an advocate for Native comics, provides a wisely ambivalent introduction. Deondre Smiles (Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe), critical geographer and academic, supplies an informative and well-illustrated essayistic postscript about the links among colonization, land theft, and deforestation. Marlena Myles (Spirit Lake Dakota), a multidisciplinary artist, provides essays, a bilingual, Dakota and English map, and strikingly stylized illustrations and endpapers. There is a meeting of talents and perspectives here that suggests careful project management (by editor Tucker Stone and editorial director and book designer Françoise Mouly). The whole definitely exceeds the sum of its parts. Paul Bunyan is the kind of project I've come to expect from TOON: distinctly individual, yet collaborative; personal, yet proactively curated by an expert editorial team. More than further proof of Van Sciver's historical imagination and cartooning chops, it's a multifaceted group effort, the kind that is needed when you're demythologizing and debunking an entrenched bit of Americana. It's a short read, but excellent, and I find myself paging through again and again with admiration.

0 Comments

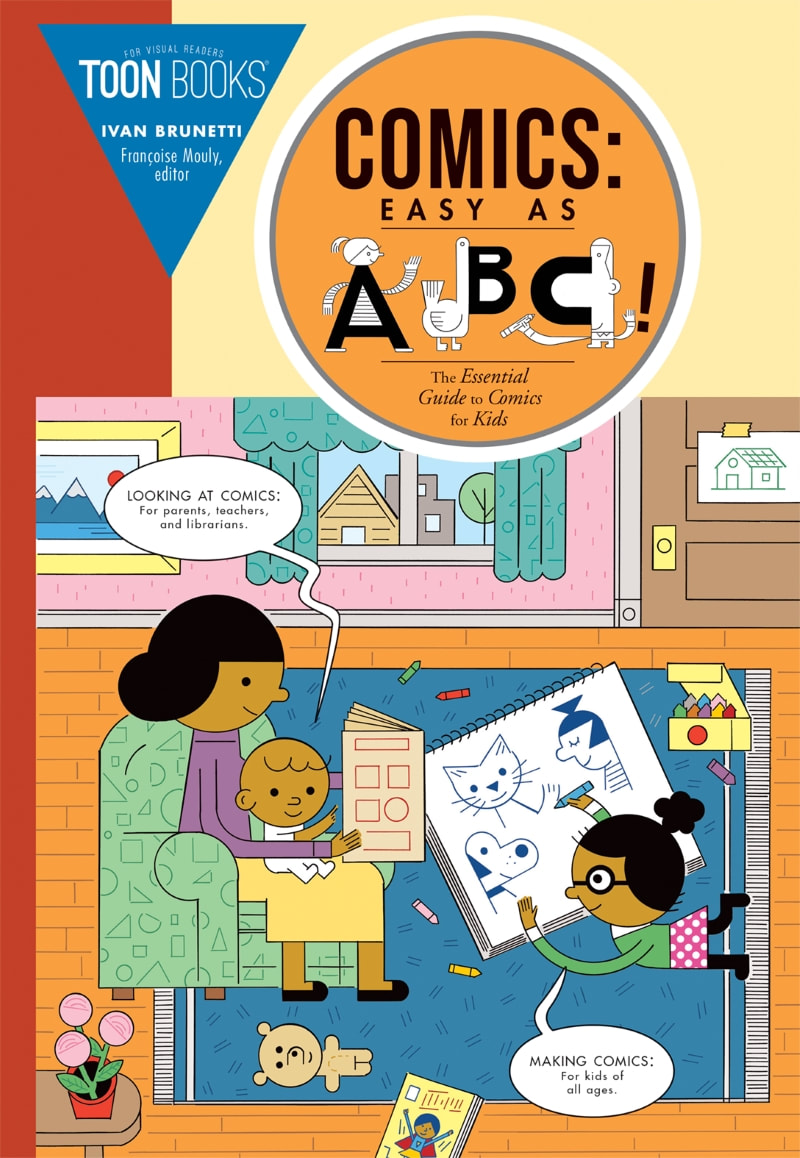

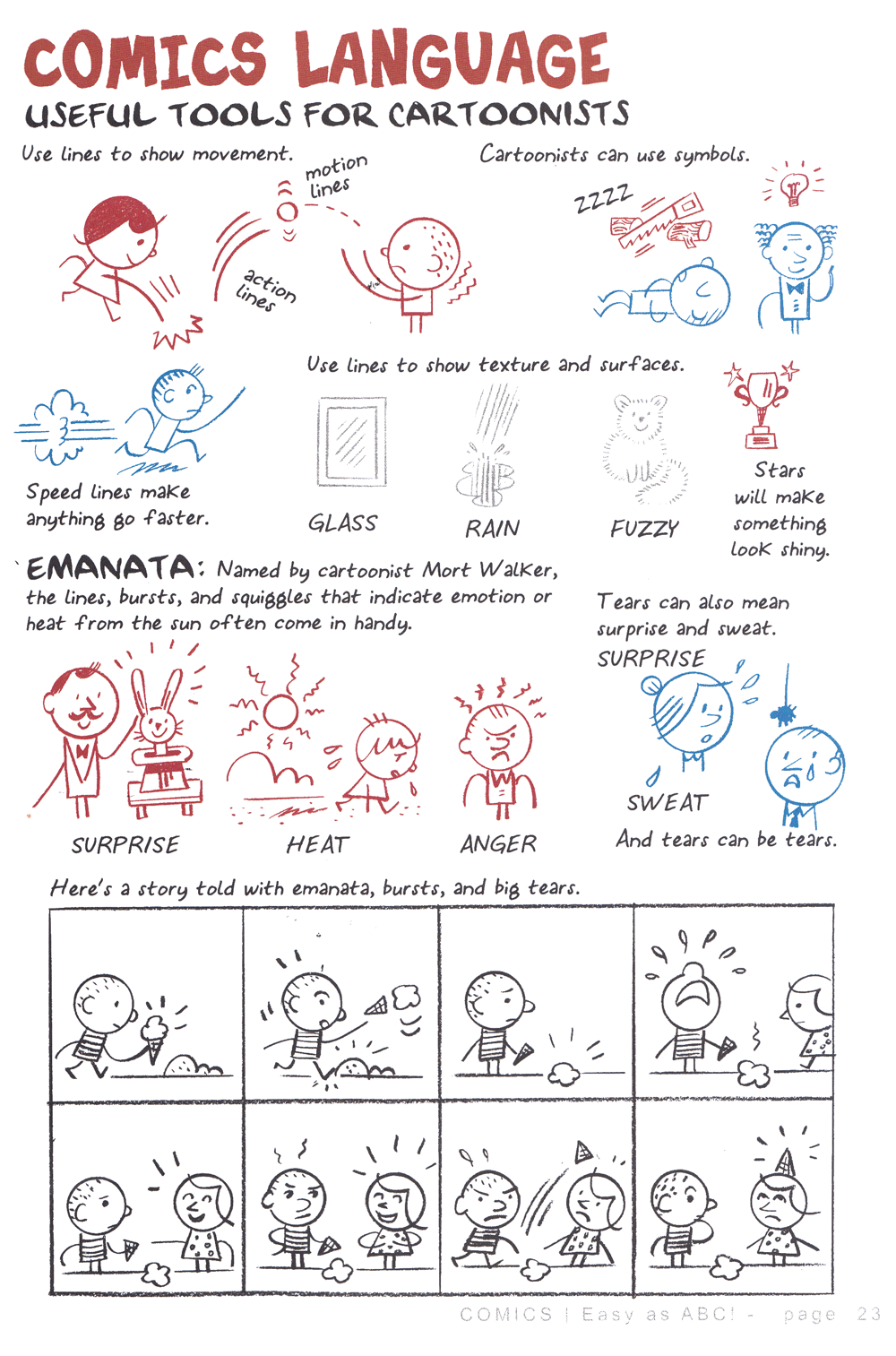

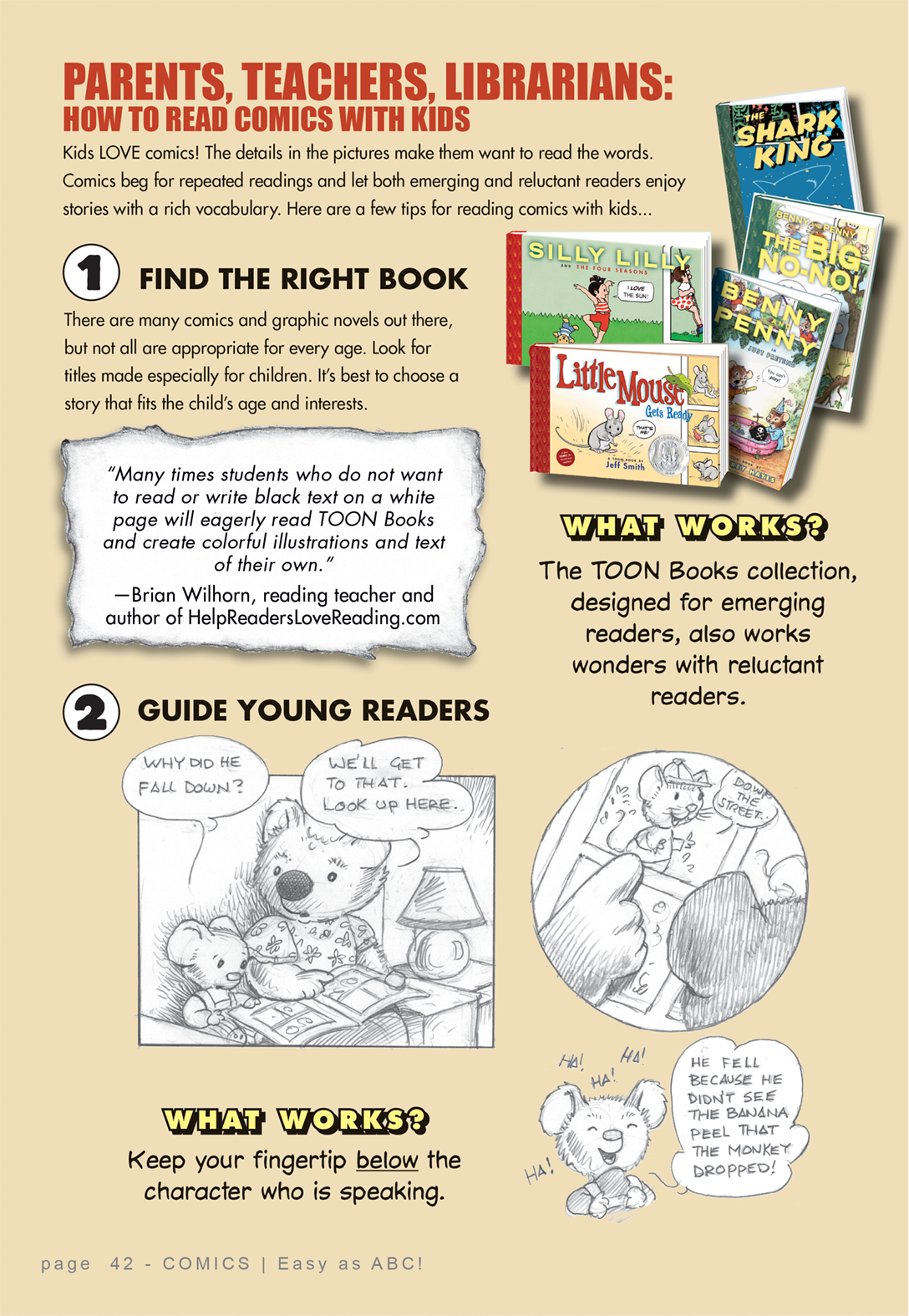

Comics: Easy as ABC! By Ivan Brunetti. Edited and designed by Françoise Mouly. With contributions by Eleanor Davis, Elise Gravel, Geoffrey Hayes, Liniers, Sergio García Sánchez, Art Spiegelman, and others. TOON Books, 2019. ISBN 978-1-943145-39-3 (softcover), $9.99; ISBN 978-1-943145-44-7 (hardcover), $16.95. 52 pages. A Junior Library Guild Selection. This is meant to be a book "for kids." I'll be using it next term as a textbook in a college class. That ought to tell you something. Comics: Easy as ABC! is both a book by Ivan Brunetti and a showcase for the entire TOON Books line. Not for nothing does the spine say Brunetti/Mouly, pointing to the crucial role of TOON's editorial director, Françoise Mouly, who commissioned, edited, and designed the book, drawing on a who's who of TOON authors to complement and fill out Brunetti's text. I imagine that this book was her idea; I note that it reuses the "coaching tips" for parents and educators found on TOON's website. In any case, Comics: Easy as ABC! works as both a young reader's adaptation of Brunetti's pedagogy, as modeled in his previous instructional book Cartooning: Philosophy and Practice (Yale, 2011), and a distillation of Mouly's (and TOON's) editorial ethos. That ethos brings kid-friendly storytelling and cartooning into contact with frank avant-gardism (shades of The World Is Round!). Who would have thought that Brunetti, author behind the scabrous, post-Crumbian Schizo and other bitter, depressive, and often savage alt-comix, would become one of TOON's signature authors, and an ambassador for children's cartooning? The mind reels. But the role suits him, and his methods can help adults as well as kids. Anyone who has carefully read (or has taught) his Cartooning textbook knows that his pedagogy is precisely the sort to encourage those who "can't draw"; Brunetti extols comic art not as illustration but as a form of "writing with pictures" accessible to almost everybody. Whereas Cartooning imagines itself as a syllabus crafted by an authoritative (and strict) teacher with a classroom of official students, Comics: Easy as ABC envisions an audience of free-spirited kids with time on their hands, doing what they want to do. A comparison to Lynda Barry's new Making Comics may help: whereas Barry exhorts her adult students and readers to recover the openness and energy of childhood drawing, Easy as ABC aims right at kids themselves (though with imagined grownups peeking solicitously over the kids' shoulders, as it were). The result is a dual-purpose book: part how-to for a young (or any aspiring) cartoonist, part exhortation to "parents, teachers, and librarians." Woven through Brunetti's pages of advice and demonstration are miscellaneous contributions from other cartoonists, with those by Elise Gravel, Sergio García Sánchez, Art Spiegelman, and the late Geoffrey Hayes being perhaps the most substantial. Benny and Penny pages by Hayes, endpapers by Gravel, a draw-your-own-conclusion strip by Spiegelman, a (too dense?) page on perspective by García Sánchez—the book is filled with diversions. Short, elliptical strips by various artists from the 4PANEL Project website insinuate an art-comics vibe by means of a traditional comics structure. Sprinkled here and there throughout the book are blurbs labeled "What works?" that offer advice either to artists or to adults coaching children through comics-reading. It's a Whitman's Sampler on the surface, a deliberate curriculum underneath. All the "extras" are good, but what most matters to me is Brunetti's teaching method. Mixing brief texts with scads of drawn examples, he starts the budding cartoonist with encouragements to doodle and experiment with basic shapes and free mark-making. He then progresses to faces, emotions, schematic character design, bodies, body language, and point of view. Eventually he gets to comics-specific devices such as emanata, word balloons, and page layout (the back matter includes an index of comics terms). Brunetti's approach is disarmingly accessible, without stinting on specific vocabulary and questions of technique. This is why I want to use this book in my university Comics class: even more than Brunetti's Cartooning, this book lays out, very clearly, basic storytelling and craft conventions that my students will need to think about as they prepare their final comics projects (and the various short exercises that will lead up to and scaffold those projects). I could quibble with some of the book's claims. Consider, for example, this exhortation to rapid-fire doodling: “When we have no time to think about the drawing, we get closer to the idea of the thing being drawn” (6). This idea that the quiddity or basic “whatness” of a thing is best conveyed without fussiness or craft, and without worrying about how to capture its visual particularities, fits Brunetti’s favored notion of comics as picture writing, but seems to deny the importance of observational drawing or the evocative this-ness of a distinctive drawing. At times, Brunetti’s advice seems designed to steer artists toward semiotically handy visual cliches. This is consistent with his ethos of writing over illustrating, and is likely to be liberating good advice for up and coming artists, but it soft-pedals the considerable effort often required to find distinctive, personal ways of rendering things as cartoons. If you believe that eloquence and distinctiveness of drawing are important, Brunetti’s embrace of simplicity and very familiar forms may grate on your nerves. On the other hand, I have given similar assurances to students in my (emphatically non-studio) classes (i.e. English classes), and I find that this sort of advice and exhortation does indeed serve to unlock visual storytelling. So, I dunno, maybe I should keep my big trap shut. In any case, I will be using this book next term! I expect it will be a great guide. It’s also a delightful read on its own terms, and a summation of what makes TOON Books such a terrific publisher.

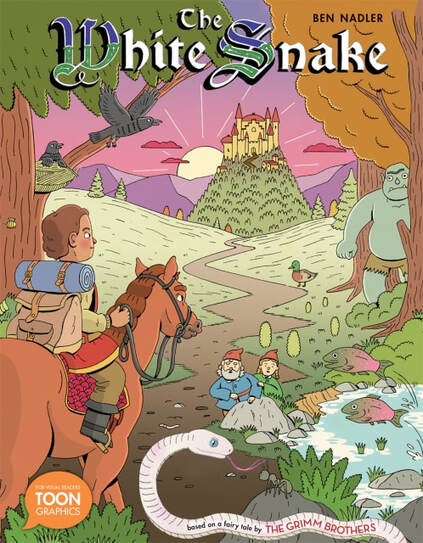

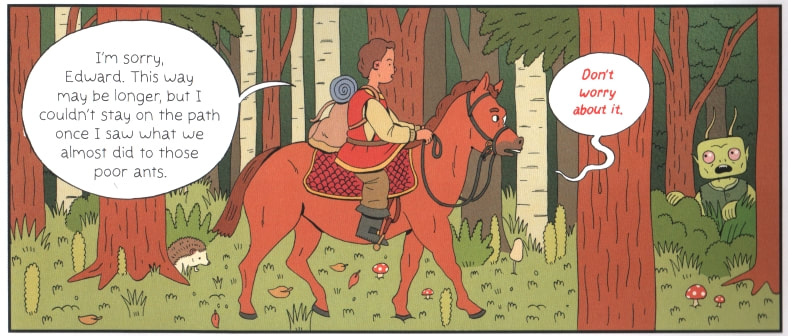

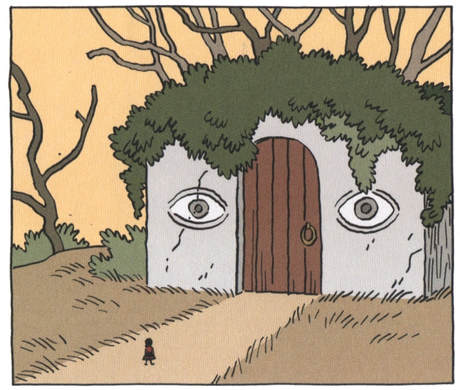

The White Snake. By Ben Nadler; based on a fairy tale by the Grimm Brothers. Edited by Paul Karasik and Dashiell Spiegelman; book design by Françoise Mouly. TOON Books, 2019. ISBN 978-1-943145-37-9 (hardcover), $16.95 ; ISBN 978-1-943145-38-6 (softcover), $9.99. 56 pages. Matter-of-fact inventiveness, marginal drollery, and a heaping helping of weirdness are the main ingredients of Ben Nadler's The White Snake, a winningly eccentric update of a Grimm Brothers fairy tale. It's a cool book. The story is about the getting of wisdom through acts of eating—literally, by taking bites of things. Its logic is less literal than symbolic, a matter of telling parallels and a neat sense of karmic payback: its hero helps various creatures who then help him in return, making it possible for him to overcome various trials. In a sense, the hero wins out because he listens and because he cares—he has a compassionate feeling toward the world around him. This helps when he is set impossible tasks that must end in either victory or death. The upshot of those tasks is that our hero must compete to win the hand of, you guessed it, a princess—but Nadler takes pains to update the tale so that the princess is no shrinking violet, but a smart leader who helps set things in motion in the first place. They become a team, and she the ruler of the land. The story ends with enlightenment (a blast of cosmic insight) and a not-too-crazy happily-ever-after that melds fairy-tale logic with progressive values. The fated parallels and connections so typical of Grimm fairy tales are preserved, the unselfconscious strangeness of folktales maintained, even as the book weaves in current feminist and environmentalist concerns. This is a considered adaptation, helped quite a bit, I gather, by the editorial input of Paul Karasik and TOON's Françoise Mouly. The results are wise as well as cool. The book’s visual style is sharp and clean, almost aseptic, with pristine lines that suggest a yen for the Ligne Claire tradition. Yet at the same time there’s an anxious, post-punk quality that, for me, recalls Mark Beyer or Henrik Drescher, and a trace of eccentric gothicists like Edward Gorey and Richard Sala. Lane Smith’s early, Klee-like work comes to mind too—also Adventure Time, and perhaps Klasky Csupo animation. Which is to say that Nadler’s mark-making, though spare, retains some nervous tics; his pages, though restrained in layout and admirably clear, hint at art-comics affinities. The look here is less the Ivan Brunetti-esque schematic minimalism of Nadler's self-published risograph comic Sonder (in which bodies tend to be clean, geometric forms) and closer to the illustrative lushness of his first book, Heretics! (a graphic history of modern philosophy, co-created with his father, philosopher Steven Nadler). But we are still a long way from naturalism here. The characters are a bit stiff, as opposed to supple; faces are schematized; action is coolly posed. The frequently oblong, page-wide panels tend to stage events and travels as if they were happening in front of a scrolling panorama. The total look implies both stability and an unrepentant oddness—well suited for the blithe absurdity of the story and its deadpan embrace of the weird. Along the way, Nadler enlivens the pages with a wealth of curious detail. There’s a great deal of whimsical chicken fat, and odd critters abound. Right from the start, you can tell that Nadler intends to draw out and reward attentive readers with all sorts of sidelong business. The result is a distinct and pleasurable graphic world, crawling with fun stuff. Like Jaime Hernandez's The Dragon Slayer (another folklore-inspired TOON Graphic "for middle grade visual readers," i.e. experienced comics readers), The White Snake is less a solo act than a group effort. It appears to have been carefully curated by TOON's editorial director Mouly and guided by input from editor Karasik, who supplies the educational back matter: a brief essay on folktales, including a frank discussion of how the book has adapted and revised the Grimms' version. All this contextualizes the book without interfering with its story or damping down its quirkiness. The result is delightfully odd—another TOON title yoking together children's literature and alt-comix aesthetics. It has put Ben Nadler on my radar, for which I'm grateful, and joins a growing smart set of folk and fairy tale-based comics. Recommended!

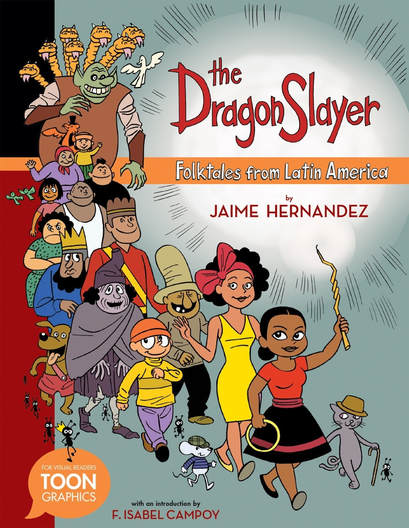

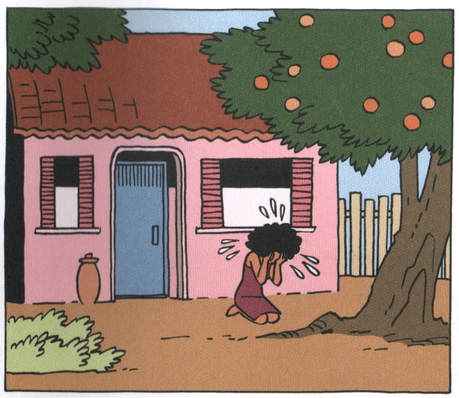

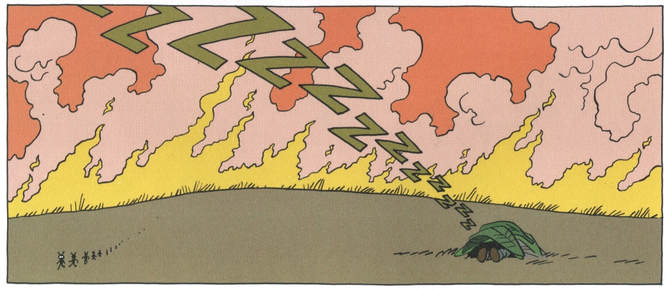

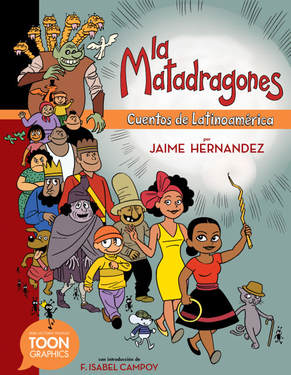

The Dragon Slayer. By Jaime Hernandez. TOON, 2018. Hardcover: ISBN 978-1943145287, $16.95. Softcover: ISBN 978-1943145294, $9.99. 40 pages. A Junior Library Guild Selection.Jaime Hernandez, one of the world's great cartoonists, is as lively and influential a comic book artist as you could hope to find. He has changed many readers' and artists' lives. His work on the Love and Rockets series (1981-now), in tandem with his brothers Mario and especially Gilbert Hernandez, proved that there was life and juice and relevance in the serial comics magazine, beyond even what many fans of the medium had dared hope. The punk, Latinx, and queer-positive aesthetic of L&R, along with its serious, in-depth storytelling and formal risk-taking, made for a revolution in comics, and Jaime Hernandez has deservedly been called one of the masters of the medium. The Dragon Slayer is not his first comic for children, as he's done a few short pieces for children's anthologies. Nor is it his first comic based on folklore: seek out for example "La Blanca," his version of a ghost story he heard from his mother, which he did for Gilbert's all-ages anthology Measles No. 2 back in 1999 (Gilbert too has made folk and family lore into comics: dig his "La Llorona," from New Love No. 5, back in 1997). Moreover, children and childhood memories are essential to Jaime's work in Love and Rockets. But The Dragon Slayer is Jaime's first real children's book. I have kid [characters] in my adult comics, but they play by my rules. Now that I’m writing for children, I’m playing by their rules. I was a little nervous because now I’m speaking directly to kids and to the parents who will let them read [the book]. So Dragon Slayer is something new for him. In fact it's a quiet collaboration: the book's back matter tells us that Hernandez read through many folktales to find the three that he wanted to adapt, and in this he was commissioned and helped by TOON's editorial director and the book's designer, Françoise Mouly. Mouly's team also deserves mention: in this case, designer Genevieve Bormes, who supplied Aztec and Maya design motifs that enliven the book's endpapers and peritexts, and editor, research assistant, and colorist Ala Lee. Like most books in the TOON Graphics line, Dragon Slayer includes some discreet educational apparatus, in the form of notes and bibliography -- more teamwork. Further, the book comes introduced by prolific scholar and children's author F. Isabel Campoy, whose collaborative book with children's author and teacher educator Alma Flor Ada, Tales Our Abuelitas Told: A Hispanic Folktale Collection (2006), is credited as one of Hernandez's sources. Campoy and Ada are key contributors here. (Another key source, albeit not as clearly announced, is John Bierhorst's 2002 collection Latin American Folktales.) All this is by way of packaging three 10-page comics by Hernandez, which are a delight, and are over too soon. I could read book after book like this from Hernandez -- the premise fits him beautifully. Hernandez has said that he liked the "wackiness" of these stories, and they do have that absurd-but-perfect, unquestionable quality of many folk tales: a sense of symbolic rightness and fated, almost-inevitable form in spite of the seeming craziness of their plots. Things happen that are preposterous and unexplained but just seem to fit, to click, because of the tales' use of repetition, parallels, rhythmic phrasing, and ritual challenges: stock ingredients, in anything but stock form. These folkloric patterns make the tales complete and rounded no matter how nonsensical they might appear at first. In crisp pages that rarely depart from a standard six-panel grid, Hernandez delivers the stories straight up, without any rationalizing or ironic distance, in clean, classic cartooning that communicates without breaking a sweat. Jaime is a master of seemingly guileless and transparent, but in fact subtle and artful, narrative drawing, and The Dragon Slayer does not disappoint. This has been billed as a "graphic novel," but it's no more a novel than other splendid TOON books like Birdsong, Flop to the Top, The Shark King, or Lost in NYC. What it is is a charming comic book that whets the appetite for more. Hernandez's cartooning benefits from the book's folkloric and scholarly teamwork, but the main thing is that the comics are marvelous. The title story, a feminist fairy tale with a light touch, focuses on an unfairly disowned youngest daughter who slays monsters and solves problems: a real pip. "Martina Martínez and Pérez the Mouse" (adapted from Ada's text) is an absurd story of marriage between a woman and a mouse, until it becomes a wise fable about panic and grief. "Tup and the Ants" is a lazy-son story in which the (again) youngest child proves his mettle with the help of a hill's worth of hard-working ants. All three comics surprised me and made me laugh out loud. I could call the book an anthology of lovely moments. It suffers no shortage of arresting moments -- panels that leap out: But what really makes these panels lovely is that there is no grandstanding in the art, only a terrific economy in visual storytelling: a streamlined delivery that carries us far, fast. Context is everything, and the book is not so much excerptable as endlessly readable. In short, The Dragon Slayer is a great book for Jaime Hernandez and for TOON, and one of the best folktale and fairy tale-based comics I've seen. I confess myself puzzled by its labeling as a TOON Graphic, which in the TOON system implies an older, more experienced comics reader, as opposed to TOON's Level 1, 2, and 3 books for beginning or emerging readers (I don't see this as a more complex comics-reading experience than, say, some of the Level 3 titles). But I do appreciate the oversized (7¾ x 10 inch) TOON Graphics format, which gives Hernandez a larger space to work in, more like that of a comics magazine. That suits his drawing and pacing. In any case, The Dragon Slayer is a sweet, short burst of smart, loving comics, and comes highly recommended. PS. A Spanish-language edition, La Matadragones: Cuentos de Latinoamérica, is also available in both hardcover (ISBN 978-1943145300) and softcover (ISBN 978-1943145317), priced as above. TOON provided a review copy of this book, in its English-language version.

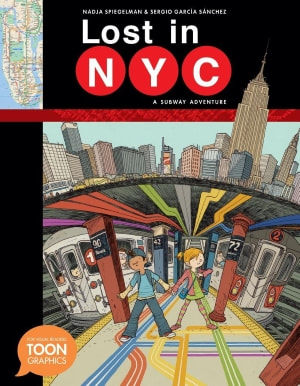

Lost in NYC: A Subway Adventure. Written by Nadja Spiegelman, illustrated by Sergio García Sánchez, and colored by Lola Moral. TOON Books, 2015. ISBN 978-1935179818. $16.95, 52 pages. A Junior Library Guild Selection. From time to time, Faves will offer brief capsule reviews of what I think of as key titles in my library: Lost in NYC is my favorite of the TOON Graphics to date (among the new books, that is—the translations of Fred's Philemon are also a delight). A short comic in picture book format, but as dense with detail as a graphic novel, Lost in NYC works in busy, hide-and-seek, Where’s Waldo? mode. It rewards attention, in fact perfectly demonstrates the idea that comics are a rereading medium. A valentine to New York and its subway system (the book is licensed by NYC's Metropolitan Transportation Authority), Lost in NYC depicts a school field trip to the Empire State Building, and gives a wealth of info about how to navigate the Big Apple (including a detailed subway map). Along the way, it tells the story of an awkward “new kid” in school who has just moved, feels out of place, and doesn’t trust anyone—until he and his field trip partner get lost and have to figure out how to rejoin their school group. The story depicts the new kid’s loneliness and bluff attempts to deny it with a rough honesty, but (unsurprisingly) reaches an uplifting conclusion: the field trip becomes a rite of passage, in a manner familiar from many picture books about first experiences. The pages, though, are the thing; they dazzle in their intricacy and attention to geography and culture. Sánchez’s cartooning is lively yet sly. The packed spreads, so much fun to wind through, turn up small surprises with each reading. Often the spreads use continuous visual narrative (i.e. repeated images of characters moving across a single page or opening) to show the kids negotiating the crowded city. Along the way, Lost in NYC has a lot to say about city life, mobility, access, and diversity (the art implies myriad mingled cultures). Thus the book invites comparison to other recent children's titles that envision cities as vast and pluralistic communities (for example, Matt de la Peña and Christian Robinson’s much-admired 2015 picture book, Last Stop on Market Street). It also tackles the challenges of moving and building new friendships. The plot is simple, and the outcome never in doubt, but the book puts the teeming cityscape to great use, not just as a backdrop, but as the main attraction. By way of bonus, Lost in NYC incorporates photos and historical facts (the field trip conceit allows a teacher character to lecture and explain); further, the book's back matter, as is typical of TOON Graphics, offers a wealth of contextual lore, social, technological, and architectural. Really, this is an overstuffed delight.

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed